Abstract

Risankizumab-rzaa (Skyrizi®; AbbVie) is a humanized IgG monoclonal antibody directed against interleukin-23p19 (IL-23p19) indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. Four pivotal Phase III trials: UltIMMa-1, UltIMMa-2, IMMhance, and IMMvent have demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. This review highlights important findings from these and other clinical trials that have evaluated risankizumab. In addition, we discuss the mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, dosing recommendations, drug interactions, other potential indications, and ongoing clinical trials.

Keywords: risankizumab, plaque psoriasis, IL-23 inhibitor, biologics, safety, efficacy

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects about 3.2% of adults in the United States.1 It is characterized by excessive inflammation with resultant hyperproliferation of keratinocytes. Skin findings associated with plaque psoriasis, the most common form of psoriasis, typically include thick, scaly, erythematous, and well-circumscribed plaques that are often pruritic and painful. Psoriasis is also associated with numerous non-dermatologic comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis,2 cardiovascular disease,3 diabetes,3 depression,4 and obesity,3 all of which can negatively impact patients’ quality of life. Psoriasis is mediated by an overactive Th1 and Th17 response, which induces cytokine dysfunction. Specifically, overactivation of IL-1, IL-17, TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-23 has been implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis.5 The use of biologic agents to target several of these inflammatory mediators is now a mainstay in treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, which encompasses approximately 20% of psoriasis cases.6

IL-23 is crucial to the pathogenesis of psoriasis, particularly in regard to differentiation and expansion of Th17 cells. It is primarily produced by dendritic cells, activated monocytes, and macrophages.7 IL-23 is composed of two subunits: IL-23p19 and IL-12p40, which combine to form the biologically active version of the cytokine. Of note, while the p19 subunit is unique to IL-23, the p40 subunit is also common to IL-12. Risankizumab-rzaa (Skyrizi®; AbbVie) is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that specifically targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. It is FDA approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. This review will provide an overview of the available evidence on the efficacy and safety profile of risankizumab for the treatment of psoriasis. In addition, it will discuss other pertinent information for prescribers to be aware of as well as important ongoing studies that are exploring potential future indications for risankizumab.

Methods

A literature search of the PubMed and Embase databases was conducted for the terms “risankizumab” and “psoriasis”. Searches were limited to English-language articles published prior to or on November 2, 2019. Results of any relevant articles were manually identified by the authors for review. Duplicate articles were excluded.

Molecular Structure and Mechanism of Action

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the p19 subunit of the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23. It is therefore more selective than certain older biologic agents such as ustekinumab, which binds to the p40 subunit that is common to both IL-12 and IL-23. Guselkumab and tildrakizumab are two biologic agents that also antagonize the p19 subunit of IL-23. However, they differ from risankizumab in that guselkumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody and tildrakizumab is a humanized IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody.8,9

Dosage

The recommended dose of risankizumab is 150 mg (two 75 mg injections) administered by subcutaneous injection at week 0, week 4, and subsequent injections every 12 weeks. There is no weight-based dosing. A Japanese phase II/III trial (SustaIMM) evaluating the safety and efficacy of risankizumab determined that when compared to a 75 mg dose at weeks 0 and 4, risankizumab 150 mg dose at weeks 0 and 4 was associated with a faster achievement of PASI 90 and PASI 100 response rates as well as higher PASI 100 at week 16, while maintaining a similar safety profile.10

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic profile of risankizumab has been derived from seven Phase I-III studies encompassing nearly 1900 patients.11–17 When administered via subcutaneous injection, the bioavailability (F) of risankizumab is 89%. Risankizumab exhibits linear and dose-dependent pharmacokinetics, as demonstrated by results in both healthy subjects (study doses ranging from 18 mg to 300 mg) and subjects with psoriasis (study doses ranging from 90 mg to 180 mg). In these studies, peak plasma concentration (Cmax) was reached in 3 to 14 days.11 The estimated Cmax and trough concentration (Ctrough) were approximately 12 mcg/mL and 2 mcg/mL, respectively.11 At the recommended dosing regimen of 150 mg administered via subcutaneous injection at week 0, week 4, and Q12W thereafter, steady-state plasma concentration is achieved by week 16.11 For a typical 90 kg patient with plaque psoriasis, risankizumab clearance is approximately 0.31 L/day with an inter-subject variability of 24%.10,12 The estimated steady-state volume of distribution (VD) is 11.2 L with an inter-subject variability of 34%.10,11 The terminal-phase elimination half-life (t½) is approximately 28 days.10,11 To our knowledge, studies evaluating the use of risankizumab in patients with renal and hepatic impairment have not been conducted thus far. The authors recommend caution when considering risankizumab use in these patients.

Pharmacodynamics

No formal pharmacodynamic studies using risankizumab have been conducted thus far.11

Drug Interactions

Khatri et al studied risankizumab’s effect on the in vivo activity of CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A enzymes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (n = 21). Following 12 weeks of dosing with risankizumab 150 mg Q4W, no clinically relevant variations in vivo activity of CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, or CYP3A enzymes were observed.18 These findings were consistent with those found in other IL-23p19 inhibitors guselkumab and tildrakizumab.19,20

Immunogenicity

Of subjects treated with risankizumab and evaluated through 52 weeks, approximately 24% of subjects (263/1079) taking the recommended dose developed antibodies to risankizumab.11 Of these subjects, approximately 57% (14% of all subjects treated with risankizumab) developed antibodies that were classified as neutralizing.10 Higher antibody titers seen in approximately 1% of subjects treated with risankizumab were associated with lower risankizumab concentrations and reduced clinical response.11

Efficacy

The key phase III clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of risankizumab were: UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370) (n = 506), UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684357) (n = 491), IMMhance (n = 507) (NCT02672852), and IMMvent (NCT02694523) (n = 605). Cumulatively, subjects in these studies had a median baseline PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) of 17.8 and median baseline BSA (body surface area) of 20.0%.10 In addition, 38% of study subjects had received prior phototherapy, 48% had received prior non-biologic systemic therapy, and 42% had received prior biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis.10 These trials are discussed individually below:

UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2

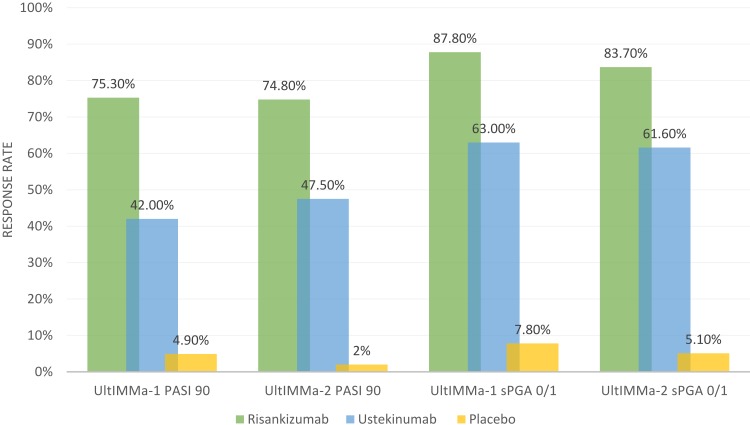

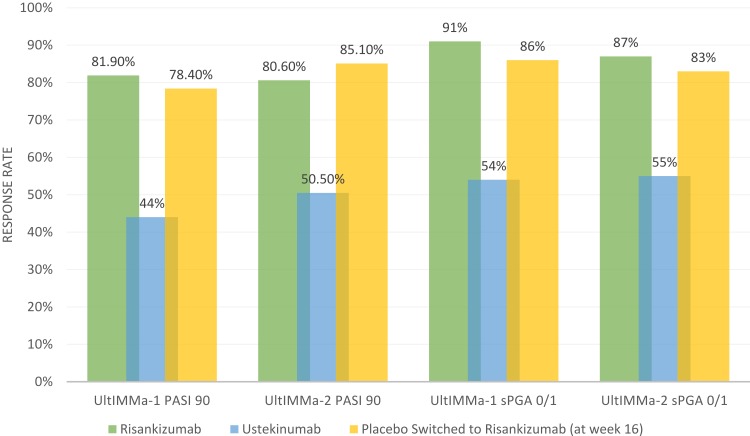

UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 were replicate, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled, randomized, phase III clinical trials.15 These studies expanded upon an earlier Phase II trial that demonstrated superiority of risankizumab when compared to ustekinumab up to 12 weeks.13 In both UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2, patients were randomized (3:1:1) to risankizumab 150 mg, ustekinumab (anti-IL-12/anti-IL-23) 45 mg or 90 mg (weight-based per label), or placebo. At week 16, patients receiving placebo were switched to risankizumab 150 mg. Subjects received subcutaneous injections at weeks 0, 4, 16, 28, and 40. The co-primary endpoints were achieving PASI 90 (achieving at least 90% clearance in psoriasis compared to baseline) and sPGA 0 or 1 (clear/almost clear with greater than or equal to 2-point improvement from baseline static Physician Global Assessment score). Notable secondary endpoints included attainment of sPGA 0 (clear), PASI 100, DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index) score of 0 or 1 (dermatologic condition having no impact on quality of life), and PSS (Psoriasis Symptom Score) of 0. In both studies, risankizumab was superior in efficacy compared to both placebo and ustekinumab (p<0.0001 vs placebo and ustekinumab).15 Week 16 and week 52 PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 results based on non-responder imputation from UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Additionally, PASI 100, sPGA 0, DLQI 0 or 1, and PSS 0 response rates at week 52 were also significantly higher for risankizumab-treated patients than for ustekinumab-treated patients.15 Regarding risankizumab durability, PASI 90 response rates were maintained through week 52. Specifically, 88.4% of patients on continuous risankizumab maintained PASI 90 compared to 73.3% on ustekinumab (p=0.0009 vs ustekinumab for both studies).15 Risankizumab also demonstrated faster response rates in patients. PASI 90 responses were significantly higher in risankizumab-treated patients starting at week 4 than in placebo-treated patients (p=0.0001; UltIMMa-1 and p<0.0001; UltIMMa-2) and at week 8 versus ustekinumab-treated patients (p<0.0001 for both studies).15 These results on clinical improvement mirror histopathologic and cytokine-induced transcriptomic changes that have demonstrated improved response to risankizumab in lesional skin compared to ustekinumab.21 Thus, the possibility of earlier clinical improvement with risankizumab may be appealing to patients who prefer a more rapid response rate when comparing biologic agents.

Figure 1.

Week 16 PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 Reponse Rates in UltIMMA-1 and UltIMMA-2. Data from Gordon et al.15

Figure 2.

Week 52 PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 Reponse Rates in UltIMMA-1 and UltIMMA-2. Data from Gordon et al.15

IMMvent

IMMvent was a multicenter, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled, randomized, phase III trial in which patients were randomized (1:1) to either risankizumab or adalimumab.16 The trial was divided into two portions: week 0 to 16 and week 16 to 44. In the first 16 weeks, patients received either risankizumab 150 mg at weeks 0 and 4 or adalimumab 80 mg at week 0 followed by 40 mg at week 1 and Q2W thereafter. After 16 weeks, patients initially randomized to adalimumab who achieved PASI 90 remained on adalimumab. Individuals who achieved less than PASI 50 were switched to risankizumab. Individuals with PASI 50 or higher but less than PASI 90 were re-randomized (1:1) to either continue adalimumab or switch to risankizumab.

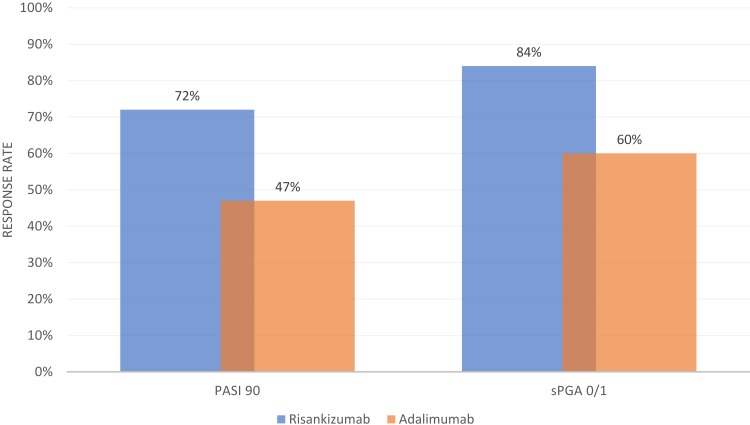

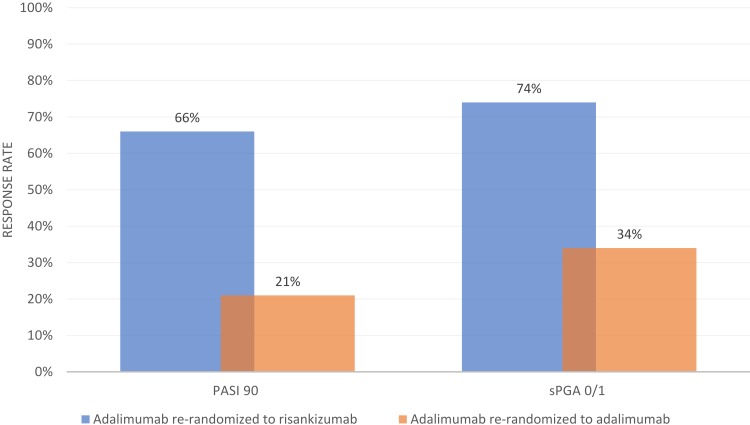

Co-primary endpoints PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 at week 16 (all patients) and PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 (re-randomized patients) at week 44 (non-responder imputation) are summarized in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. At week 16, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving risankizumab achieved PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1, as well as PASI 75, PASI 100, and sPGA 0 (p<0.0001 for all endpoints).16 Among adalimumab intermediate responders at week 16 (50 ≤PASI <90), a larger proportion of individuals who were re-randomized to risankizumab achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 at week 44 as compared to those who continued adalimumab.16 As with UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2, all primary and ranked secondary endpoints were achieved in IMMvent.15,16 Patients who received risankizumab continuously throughout the study generally maintained PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 from week 16 to week 44.16 The data for these particular outcomes was not published, however. Additionally, as seen when risankizumab was compared to ustekinumab in UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2, the proportion of patients achieving PASI 90 in IMMvent was significantly higher in patients receiving risankizumab when compared to adalimumab starting at week 8.15,16

Figure 3.

Week 16 PASI 90 and SPGA 0/1 Response Rate in IMMvent. Data from Reich et al.16

Figure 4.

Week 44 PASI 90 and SPGA 0/1 Response Rate in Re-randomized Subjects in IMMvent. Data from Reich et al.16

IMMhance

IMMhance was a confirmatory, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial with randomized withdrawal and re-treatment comparing risankizumab 150 mg with placebo.16 The co-primary efficacy endpoints were achievement of PASI 90 and sPGA 0/1 at week 16 and sPGA 0/1 at week 52 (among re-randomized patients). The trial was split into two portions, part A1 and part B. In part A1 (weeks 0 to 16), patients were randomized 4:1 to either risankizumab 150 mg or placebo at weeks 0 and 4. In Part B (weeks 16 to 52), patients originally randomized to risankizumab who achieved sPGA 0/1 at week 16 were re-randomized (1:2) at week 28 to either risankizumab 150 mg or placebo Q12W. At week 52, PASI 90, PASI 100, and sPGA 0/1 were significantly greater (p<0.001) in patients maintained on risankizumab when compared to patients re-randomized from risankizumab to placebo. At week 52, 87.4% and 85.6% of patients maintained on risankizumab achieved sPGA 0/1 and PASI 90, respectively. In comparison, 61.3% and 52.4% of patients switched from risankizumab to placebo achieved sPGA 0/1 and PASI 90, respectively.16 Of note, IMMhance provided a timeframe for the loss of efficacy observed in patients switched off of risankizumab. Median time to sPGA ≥3 in those who originally achieved sPGA 0/1 was significantly different between the patients re-randomized to continuous risankizumab (not determinable because so few patients lost response) compared with placebo (288 days) (p<0.001).16

Other Studies

Sawyer et al conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 77 randomized control trials with a total of 34,816 patients to compare anti-IL-17 agents to anti-IL-23 agents.22 Included trials that evaluated risankizumab were UltIMMa-1, UltIMMa-2, IMMvent, and IMMhance. When compared to brodalumab (anti-IL-17 receptor), ixekizumab (anti-IL-17A), and guselkumab (anti-IL-23), risankizumab was not statistically significant in achieving higher PASI 75, PASI 90, or PASI 100 response rates.22 However, risankizumab, along with brodalumab and ixekizumab, was significantly more efficacious than secukinumab, while guselkumab was not.22 Both guselkumab and risankizumab were more efficacious than tildrakizumab, ustekinumab, all TNF inhibitors, and non-biologic systemic treatments at inducing all levels of PASI response rates.22 Overall, all anti-IL-17 agents, guselkumab, and risankizumab were more efficacious than tildrakizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and certolizumab, which in turn were more efficacious than etanercept, apremilast, and dimethyl fumarate.22 A separate network meta-analysis of 27 phase II and phase III randomized control trials (n = 19,840) that compared short-term efficacy and safety data of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors found that risankizumab 150 mg performed better than ustekinumab 45 mg (RR=1.24, 95% CI 1.12–1.37) and brodalumab 140 mg (RR=1.70, 95% CI 1.12–1.44) with regard to achieving PASI 75 at week 12 or 16.23 Additionally, risankizumab 150 mg had a lower risk of adverse events and serious adverse events compared with other IL-23 inhibitors, showing relatively high clinical efficacy and low treatment risk.23 Of note, this network meta-analysis only included UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 and did not include a comparison of PASI 90 scores because earlier clinical trials evaluating biologic agents used PASI 75 as the primary efficacy endpoint. Witjes et al performed a meta-analysis to assess risankizumab efficacy as compared to adalimumab, independently of IMMvent, which is the only head-to-head clinical trial comparing risankizumab and adalimumab. The meta-analysis (n=3767) compared the efficacy of adalimumab in five placebo-controlled clinical trials24–28 to the efficacy of risankizumab in UltIMMa-1, UltIMMa-2 and IMMhance. As with IMMvent, risankizumab demonstrated superior efficacy when compared to the efficacy of adalimumab, as demonstrated by the head-to-head results in IMMvent.

Safety Profile

The safety profile of risankizumab is comparable to other biologic agents, although the evaluation of long-term safety data beyond 52 weeks is ongoing at this time. In UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2, risankizumab was found to have a similar safety profile to placebo and ustekinumab through week 16, with no meaningful differences in the following four safety evaluations: adverse event rates, serious adverse event rates, severe adverse event rates, and rates of an adverse event leading to discontinuation of study drug.15 Through week 52, the overall safety profiles and rates of infection were similar across risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo treatment groups, although infections were more frequently reported in patients receiving risankizumab or ustekinumab compared with those receiving placebo.15 The rates of serious infections for the risankizumab group and the placebo group were ≤0.4%.11,15 Serious infections in the risankizumab group included cellulitis, osteomyelitis, sepsis and herpes zoster.11,15 IMMhance, which occurred after UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2, did not identify any new safety concerns when comparing placebo to risankizumab.16 Risankizumab was also found to have a similar safety profile to adalimumab in IMMvent.16 In general, the most frequently reported adverse events (occurring in ≥5% of subjects) in patients receiving risankizumab were viral upper respiratory tract infections, upper respiratory tract infections (unspecified), diarrhea, urinary tract infections, influenza, and headache14–16 As is consistent with the prescribing practices of other biologic medications, patients should be evaluated for tuberculosis prior to initiating therapy and should not receive live vaccines while being treated with risankizumab. Preliminary pooled safety data from nine Phase I through III clinical trials has shown comparable safety profiles in both short-term and long-term follow-up in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients.29

Conclusion

As the number of biologic agents used to treat psoriasis expands, newer medications provide promise of enhanced efficacy. In phase III trials conducted thus far, risankizumab has proven to be both efficacious and safe in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. By specifically targeting the IL-23p19 subunit and thereby blocking the Th-17/IL-23 pathway, risankizumab, when compared to other more non-specific agents, may have a lesser impact on normal immune function. The head-to-head phase III clinical trials discussed in this review have demonstrated that risankizumab is superior to ustekinumab and adalimumab in efficacy, including time to visible clinical improvement, and comparable in its safety profile. Currently, one phase III clinical trial comparing risankizumab and secukinumab for subjects with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis is ongoing.30 Another ongoing phase III trial is evaluating the efficacy of risankizumab compared to methotrexate.31 Long-term efficacy and safety data of risankizumab is pending.32 In addition, ongoing studies are also examining the potential for utilization of risankizumab for other indications. Specifically, these trials are assessing the use of risankizumab for Crohn’s disease33–36 atopic dermatitis,37 psoriatic arthritis,38,39 erythrodermic and generalized pustular psoriasis,40 and ulcerative colitis.41

Disclosure

WL is funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (U01AI119125) and National Psoriasis Foundation, and has received research funding from Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Trex Bio. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):251–265.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Silverberg JI. Under-screening of depression in United States outpatients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang C, Chen S, Qian H, Huang W. Interleukin-23: as a drug target for autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Immunology. 2012;135(2):112–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03522.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp K, Thaçi D, Reich K, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(4):930–939. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon KB, Duffin KC, Bissonnette R, et al. A Phase 2 trial of guselkumab versus adalimumab for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):136–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsuki M, Fujita H, Watanabe M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the SustaIMM phase 2/3 trial. J Dermatol. 2019;46(8):686–694. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=761105. Accessed October30, 2019.

- 12.Suleiman AA, Minocha M, Khatri A, Pang Y, Othman AA. Population pharmacokinetics of risankizumab in healthy volunteers and subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: integrated analyses of Phase I–III clinical trials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(10):1309–1321. doi: 10.1007/s40262-019-00759-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1551–1560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):116–124.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled Phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650–661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31713-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaçi D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2019;394(10198):576–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30952-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langley R, Blauvelt A, Gooderham Met al,. Efficacy and safety of continuous Q12W risankizumab versus treatment withdrawal: results From the phase 3 IMMhance Trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):AB52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatri A, Cheng L, Camez A, Ignatenko S, Pang Y, Othman AA. Lack of effect of 12-Week treatment with risankizumab on the pharmacokinetics of cytochrome P450 probe substrates in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(6):805–814. doi: 10.1007/s40262-018-0730-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pharmacokinetic Study to Evaluate the Effect of a Single Dose of Guselkumab (CNTO 1959) on CYP 450 Enzyme Activities After Subcutaneous Administration in Participants With Psoriasis - Full Text View- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02397382. Accessed October31, 2019.

- 20.Khalilieh S, Hussain A, Montgomery D, et al. Effect of tildrakizumab (MK-3222), a high affinity, selective anti-IL23p19 monoclonal antibody, on cytochrome P450 metabolism in subjects with moderate to severe psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(10):2292–2302. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visvanathan S, Baum P, Vinisko R, et al. Psoriatic skin molecular and histopathologic profiles after treatment with risankizumab versus ustekinumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2158–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawyer LM, Malottki K, Sabry-Grant C, et al. Assessing the relative efficacy of interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 targeted treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of PASI response. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai F, Li GG, Liu Q, Niu X, Li R, Ma H. Short-term efficacy and safety of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors brodalumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Immunol Res. doi: 10.1155/2019/2546161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab to Methotrexate and Placebo in Subjects With Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00235820. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 25.Efficacy and Safety of Adalimumab in Subjects With Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00237887. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 26.A Study of Guselkumab in the Treatment of Participants With Moderate to Severe Plaque-Type Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02207231. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 27.A Study of Guselkumab in the Treatment of Participants With Moderate to Severe Plaque-Type Psoriasis With Randomized Withdrawal and Retreatment - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02207244. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 28.A Study to Evaluate CNTO 1959 in the Treatment of Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque-type Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01483599. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 29.Leonardi C, Bachelez H, Wu Jet al,. Long-term safety of risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: analysis of pooled clinical trial data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4, Supplement 1):AB234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Risankizumab Versus Secukinumab for Subjects With Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03478787. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 31.A Study Comparing the Safety and Efficacy of Risankizumab to Methotrexate in Subjects With Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03219437. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 32.A Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of Risankizumab for Maintenance in Moderate to Severe Plaque Type Psoriasis (LIMMITLESS) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03047395. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 33.A Long Term Extension Trial of BI 655066/ABBV-066 (Risankizumab) in Patients With Moderately to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02513459. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 34.A Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Risankizumab in Subjects With Moderately to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease Who Failed Prior Biologic Treatment - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03104413. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 35.A Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Risankizumab in Subjects With Moderately to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03105128. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 36.A Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Risankizumab in Subjects With Crohn’s Disease Who Responded to Induction Treatment in M16-006 or M15-991; or Completed M15-989 - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03105102. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 37.A Study to Evaluate Risankizumab in Adult and Adolescent Subjects With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03706040. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 38.A Study Comparing Risankizumab to Placebo in Subjects With Active Psoriatic Arthritis Including Those Who Have a History of Inadequate Response or Intolerance to Biologic Therapy(Ies) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03671148. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 39.A Study Comparing Risankizumab to Placebo in Subjects With Active Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) Who Have a History of Inadequate Response to or Intolerance to at Least One Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03675308. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 40.A Study to Assess Efficacy and Safety of Two Different Dose Regimens of Risankizumab Administered Subcutaneously in Japanese Subjects With Generalized Pustular Psoriasis or Erythrodermic Psoriasis - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03022045. Accessed November4, 2019.

- 41.A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled Induction Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Risankizumab in Subjects With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis Who Have Failed Prior Biologic Therapy - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03398148. Accessed November4, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=761105. Accessed October30, 2019.