Abstract

Background:

Effectiveness evidence of complementary therapies in people with advanced disease is uncertain, and yet people are still keen to engage in complementary therapy. Insights into people’s experiences of complementary therapy in palliative care, the perceived benefits, and how they want it delivered, can inform clinical guidelines and suggest ways to test therapies more appropriately in future evaluations.

Aims:

Explore in people with advanced disease (1) the experiences and perceptions of benefits and harms of aromatherapy, massage, and reflexology and (2) how they would like these therapies delivered.

Design:

A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Database search terms were related to palliative care, aromatherapy, reflexology and massage. Citations and full texts were reviewed independently against predefined inclusion criteria. Studies were appraised for quality. This review is registered at PROSPERO (22/11/2017 CRD42017081409).

Data sources:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, CINAHL, KoreaMed and ProQuest with a bibliography search to June 2018.

Results:

Five qualitative studies in advanced cancer were identified. Three analytical themes were identified: (1) Experience during the therapy (enhanced well-being and escapism), (2) beyond the complementary therapy session (lasting benefits and overall evaluation), and (3) delivery of complementary therapy in palliative care (value of the therapist and delivery of the complementary therapy).

Conclusions:

People with advanced cancer experience benefits from aromatherapy, reflexology and massage including enhanced well-being, respite, and escapism from their disease. Complementary therapy interventions should be developed in consultation with the target population to ensure they are delivered and evaluated, where feasible, as they wish.

Keywords: Complementary therapy, aromatherapy, reflexology, massage, advanced cancer, palliative, systematic review, and thematic synthesis

What is already known about the topic?

Conventional therapies are not always sufficient to provide satisfactory relief of symptoms to those at an advanced stage of a disease.

Evidence on the effectiveness of complementary therapies improving the well-being of people with advanced diseases is uncertain; however, palliative care services often offer such therapies as a way to reduce stress and promote relaxation.

A systematic review of qualitative studies found cancer patients (irrespective of disease stage) viewed complementary therapies as providing a sense of physical and psychological well-being.

What this paper adds

Participants with advanced cancer perceived an improvement in their physical and psychological well-being during and after the complementary therapy session.

Participants with advanced cancer experienced a form of escapism or living in the moment that took away their worries about their disease and future.

Participants with advanced cancer highlight how they would like the complementary therapy delivered including the importance of building a special relationship with the complementary therapist and a need for more frequent sessions.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Hospices and other palliative care environments should continue/consider offering aromatherapy, reflexology and massage where possible and it should be seen as an important aspect of the palliative care people receive.

Researchers should develop complementary therapy interventions in the ways in which the palliative care population, with cancer and other advanced diseases, wish them to be delivered.

Introduction

People with advanced disease (i.e. not amenable to cure) often experience a range of psychological health problems such as low mood, anxiety and depression.1 These health problems can stem from concerns regarding pain, leaving loved ones behind, and an anticipation of mortality.2 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that people with advanced diseases should have their psychological and physical needs met.3 Furthermore, the World Health Organization stated palliative care should aim to provide relief from pain and improve quality of life.4 However, conventional therapies, drug and non-drug interventions, are not always sufficient to provide satisfactory relief.5 Moreover, providers of palliative care recognize the limitations in the services they provide, for example, a national survey in the United Kingdom found palliative care clinicians report difficulties in managing patient anxiety.6 Therefore, it is important to explore other avenues that may improve well-being and symptoms in a palliative care population.

Complementary therapies are often used alongside conventional therapies to help relieve symptoms and improve well-being.7,8 Several reviews have found non-contact complementary therapies, such as music therapy, are beneficial for people in palliative care by reducing their pain and improving their psychological well-being.9–11 Acupuncture, although it is a form of physical complementary therapy, does not involve physical contact from the therapist and has mixed findings with regards to its effects on pain, psychological well-being and quality of life in the palliative care population.12–14 The effectiveness of therapies which involve a form of therapist touch, such as aromatherapy, massage and reflexology, is also uncertain.15–19 The most popular complementary therapies found in the 21-country European Social Survey are manual body-based therapies such as aromatherapy, massage, and reflexology, and are therefore the focus of this review.20

Despite the lack of evidence, people remain keen to engage in complementary therapies.21,22 A qualitative synthesis (an analytical review of qualitative studies) can be used to aid the understanding of the findings from effectiveness reviews by exploring people’s experiences of interventions or treatments.23 In addition, qualitative syntheses can help inform guidelines and health decision-making.24 A previous qualitative synthesis that focused on all complementary therapies for people at any stage of cancer found participants perceived these therapies to improve their physical and psychological well-being, gave a sense of control, and allowed a connection to build with the therapist.25 Our review will build on these findings by providing an update of this literature while focusing on aromatherapy, massage and reflexology as these are commonly provided in palliative care and to facilitate a more in depth analysis. Furthermore, beyond the participants’ experiences, we will explore how they prefer these therapies to be delivered to help inform future intervention design.

Methods

This is a review using thematic synthesis methodology and was selected following identification of the included studies and was based on the studies descriptive nature. Moreover, the aim of our research was to analyse and aggregate findings from individual studies rather than to develop new theoretical constructs for which other synthesis methods may have been more appropriate. Our approach to thematic synthesis was based on the guidelines described by Thomas and Harden26 and informed by guidance from the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group.

The synthesis is reported followed the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) guidelines.27 The synthesis approach used to combine the qualitative evidence was based on the type of data we found in the included studies.28 We considered whether the data within the studies could enable us not only to provide an understanding of the value (or harm) of complementary therapy but also in what contexts (e.g. for whom and when).

The review protocol is registered on the PROSPERO database (22/11/2017 CRD42017081409). Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017081409. Other aspects of the review programme are in-progress.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they used qualitative methods in their approach to data collection and analysis, and if (1) participants were aged 18 years or over and (2) 50% or more were in a palliative care setting (e.g. hospices) or who were described as having an advanced disease and were being treated with palliative intent, and (3) participants discussed their experience of aromatherapy, reflexology and/or massage. We did not exclude studies if they discussed complementary therapy in general as long as it was possible to extract data on people’s perspectives specific to aromatherapy, massage or reflexology.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Database searches were conducted from inception to December 2017 in: The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register: The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), AMED (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), KoreaMed and ProQuest. Variations of the terms ‘palliative’, ‘aromatherapy’, ‘reflexology’ and ‘massage’ were used as search terms. To ensure all relevant search terms were identified, MeSH and CINAHL subject headings were used to create the search term list for each database platform (for OVID example see Supplemental Appendix 1). For any relevant studies, we undertook backward and forward citation searching to identify any further studies and contacted authors of relevant studies to ask if they knew of any studies we had missed. An updated search was conducted in June 2018.

Screening was undertaken in duplicate independently. One author (M.A.) screened all citations and other authors (B.C./N.K./S.W.) each screened one third. When the title and abstract appeared relevant or did not have sufficient information to inform exclusion, full-text papers were retrieved. Eligibility of papers was discussed with the screening authors. Any discrepancies in eligibility at screening and at full text were discussed for resolution by the wider review team (P.S./K.F.). Reasons for exclusions of any studies were documented.

Quality assessment

It was agreed a priori that all studies would be included in the synthesis regardless of their quality due to the predicted small amount of studies and the ongoing debate regarding whether qualitative research can appropriately be assessed for quality.29 The nine-item Hawker quality assessment tool was used to explore the methodological rigour of the primary studies.30 The items were assessed using a four-point scale ranging from ‘good’ to ‘very poor’ and related to the abstract, reported method, sampling, analysis, ethics and bias, generalisability and implications.

Thematic synthesis

The articles were analysed according to the three steps outlined in thematic synthesis methodology: (1) line-by-line coding of text, which involves categorizing pieces of text according to its meaning; (2) development of descriptive themes by grouping codes together based on their similarities and in answer to our research questions; and (3) generation of analytical themes by considering the descriptive themes in relation to developing a framework of how the participants experience, value and want the complementary therapy to be delivered.26 First, the results sections of the papers were imported into NVivo 10 software and the first author (M.A.) coded each line of text from the results sections based on its meaning. Second, two authors (M.A. and B.C.) looked for similarities and differences among these codes and grouped them into descriptive themes. Third, these descriptive themes were placed under higher-order themes to generate analytical themes based on our research aims.

Results

Study characteristics

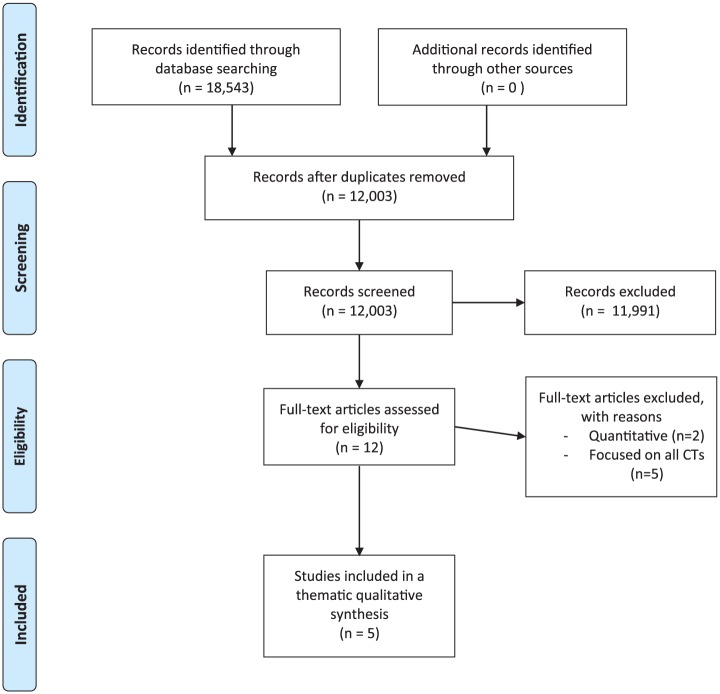

From our systematic search, five relevant qualitative studies were identified.31–35 A flow diagram of the review selection process is provided in Figure 1 and the characteristics of the five studies are shown in Table 1. Three studies focused on massage,31,32,36 one on aromatherapy34 and one on reflexology.35 All participants from the five studies (n = 83) had advanced cancer and were predominately female (n = 70). The studies were conducted in Sweden (n = 3) and the United Kingdom (n = 2). The complementary therapies were conducted in nursing homes/hospices,31,35 at the participants’ homes,33 and at an oncology ward.32 One study did not specify a location.34 The complementary therapies were provided by nurses,31,32,34 the study authors trained in complementary therapy32,33 and a trained reflexologist.35 Research approaches used were phenomenology (n = 3) and thematic analysis (n = 2) and data were mainly collected through one-to-one interviews (n = 3);31–33 one study used focus groups34 and one study used self-reported open-ended questionnaires.35

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of primary studies.

Table 1.

Primary study characteristics (n = 5).

| Author (year), country | Title | Main aims | Study setting | Interventionist | Research methodology | Data collection | Study population | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck et al.,31 Sweden | To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care | To explore how people with incurable cancer experienced soft massage, given as an established and integrated part of palliative home care. | The soft massage was delivered at the nursing home and the interviews were conducted at the participants homes (n = 7) or at the hospice (n = 1). | Three palliative care nursing assistants | Phenomenological approach | Tape recorded interviews | Eight people (5 women, 3 men) between the ages of 48 and 82 years old with advanced cancer | Feeling dignified and cared for. Being able to give responsibility to someone else and relax. Becoming free from physical suffering during the massage and heavy thoughts. Experiencing a sensation of floating away in time and space. |

| Billhult and Dahlberg32, Sweden | A meaningful relief from suffering: experiences of massage in cancer care | To explore if massage, from the patient’s point of view, increases well-being and how they experience the massage. | Massaged and interviewed in the oncological ward. | Healthcare workers (trained by the first author) and the first author | Phenomenological approach | Tape recorded interviews | Eight female cancer patients (six with advanced cancer) aged 54-80 years old. | A feeling of being ‘special’ and no longer anonymous in hospital setting. Development of a positive relationship with the masseuse. A feeling of being strong. It feels good and gives a sense of feeling good. |

| Cronfalk et al.,33 Sweden | The existential experiences of receiving soft tissue massage in palliative home care - an intervention | To explore how patients with cancer in palliative home care experienced soft tissue massage |

Massaged and interviewed at participants’ homes | The first author who was a qualified massage therapist | Phenomenological approach | Tape recorded interviews | 22 participants with advanced cancer (14 women, 8 men) aged 41 to 76 years old. | A time of existential respite (‘A moment of complete rest from illness’). Building a positive relationship with the therapist and being given personal attention was important. Feelings of relaxation, joy, satisfaction and respite. |

| Dunwoody et al.,34 UK | Cancer patients’ experiences and evaluations of aromatherapy massage in palliative care | To explore the patients’ experiences of aromatherapy | Unknown | A nurse | Thematic analysis | Focus group with a semi-structured interview | 11 (10 females, 1 male) palliative care patients with metastatic disease aged 40-60 years old. | De-stressing Counselling role of the aromatherapists Felt it was reward and time for themselves (self care) Empowerment in leading their treatment plan Felt secure in the hospice (especially after surgery) and would not want to use private practices Wanted more sessions and more frequently |

| Gambles et al.,35 UK | Evaluation of a hospice based reflexology service: a qualitative audit of patient perceptions | To explore of patient perceptions of reflexology |

Questionnaires filled out in patients own environment of choice. | Trained reflexologist | Thematic analysis | Semi-structured questionnaire | 34 participants (33 females, 1 male) with cancer attending a palliative care unit | Relaxation during treatment. Helping with coping and reducing anxiety. Giving ‘time out’. Improved sleep and appetite. Important to have a friendly atmosphere of environment and staff. |

Quality assessment

Using the Hawker scale, we judged that all five papers provided clear titles, abstracts and introductions. We also found that studies gave a good justification of the method they used, and a clear description of the data collection and results. They also all gave clear implications for clinical practice and research. However, two studies failed to provide a clear justification for the selection of their sample, which meant there could be some sample bias.31,32 Furthermore, one study did not refer to ethical approval or discuss any ethical issues.34 Overall, the five studies all had reasonable to good quality (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of included studies (n = 5) using the Hawker et al.30 tool.

| Source paper | Title of paper | Abstract and title | Introduction and aims | Method and data | Sampling | Data analysis | Ethics and bias | Results | Transferability | Implications | Quality score (out of 36) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck et al.31 (N = 12) | To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care | 4 - good structured abstract with all information although it could be argued title not entirely clear as type of study not stated. | 3 - literature review and aims given but no objectives | 4- good description of data collection and recording methods | 2 - provides details of sample but does not provide justification of selection of sample | 4 - clear description of how analysis was made | 4 - ethical approval report, researchers declared their previous understandings | 4 - finding relate to aims and are supported by quotes | 2 - the context and setting of the research are well described | 4 - clear conclusion with implications for both practice and research | 31 |

| Billhult and Dahlberg32 (N = 8 female patients) | A meaningful relief from suffering: experiences of a massage in cancer care | 4 - title and abstract clear | 3 - good literature review and key aim given but no objectives | 4 - clearly explained | 2 - sample size not justified, and focusing on women not justified. | 3 - methods used for analysis clearly outlined; however they do not state if analysis conducting in duplicate | 4 - ethics approval and bias of researcher discussed | 4 - findings linked to aims and example quotes given | 2- context described in discussion but low sampling score reduced transferability | 4 - under researched area and future directions discussed | 30 |

| Cronfalk et al.33 (N = 22) | The existential experiences of receiving soft tissue massage in palliative home care: an intervention | 3 - Abstract clearly structured. However, title somewhat misleading | 3 - good literature review and clear aim but no objectives | 4 - clearly explained | 4 - presample size determined and characteristics given in detail | 4 - analysis and themes outlined clearly | 4 - ethical approval and a section on the ethical considerations for this sample | 4 - findings linked to the key aim and quotes given | 4 - some context given at end of the discussion on limits of transferability but also threaded throughout discussion | 4 - clinical implications discussed as well as future directions | 34 |

| Dunwoody et al.34 (N = 11) | Cancer patients’ experiences and evaluations of aromatherapy massage in palliative care | 3 - title clear but abstract lacking from details such as sample size | 3 - literature review clear and aim clear but no objectives | 4 - method clear | 4 - clear justification for sample size and selection | 4 - techniques used clear | 1 hardly any discussion of ethical issues and no mention of ethical approval | 4 - results are detailed and supported with quotes | 2 - context was not always given in discussion and only a brief mention in the limitations | 4 - implications discussed in detail | 29 |

| Gambles et al.35 (N = 34) | Evaluation of a hospice based reflexology service: a qualitative audit of patient perceptions | 4 - title and abstract clear | 3 - literature review clear but no clear aims and objective | 4- method is clear | 4 - clear justification for sample and the size of sample | 3 - technique used clearly outlines; however, does not state if analysis conducted in duplicate | 3 - no mention of approval from an ethical body but discusses the ethical issues throughout paper | 4 - results are detailed with plenty of supportive quotes | 4 - context is discussed throughout the discussion | 4 - implications and further research suggested | 33 |

Data synthesis results

Data from all studies were featured in each of the generated themes, which represented the views of people receiving complementary therapy in palliative care. Each theme was distinctive, although for some there was a level of overlap. Six descriptive themes were generated on how people with advanced cancer experience complementary therapy, what were the perceived benefits and how they wanted it to be delivered. Themes were (1) enhanced well-being, (2) a feeling of escapism, (3) having lasting positive benefits, and (4) the distinct value of the therapist. A fifth theme was related to people providing an overall evaluation of complementary therapy as something positive but whose benefits were often subtle, wide-ranging and difficult to describe. A sixth theme was on the delivery of the complementary therapy. These themes were grouped into analytical themes to allow a broader understanding of the experience of complementary therapy in palliative care. These analytical themes were (1) experience during complementary therapy, (2) lasting benefits beyond the complementary therapy session, and (3) the process of complementary therapy in palliative care in relation to its delivery. See Table 3 on relationship between themes and codes.

Table 3.

Relationships between codes, themes and analytical themes.

| Analytical themes | Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Experience during the therapy | Enhanced well-being Feeling of escapism [from disease/situation] and living in the moment |

Calming Feeling dignified/self-worth, empowered, good/whole Feeling in control/safe Helps manage living with disease, reduces anger and loneliness, reduces anxiety Relieve from suffering Time for your self Altering time Engage spiritually and religiously, transcendence, gives a feeling of peace Feeling free Feeling normal Living in the moment Floating away |

| Beyond the complementary therapy session | Lasting benefits Overall evaluation |

Creates positive memories Gives lasting pleasure, feeling good, feeling happy Gives hope Helps me sleep Reduces side effects Unable to describe in detail the positive experience A reward Appreciate as has no harsh effects |

| The process of delivery of complementary therapy in palliative care | Distinct value of therapist Delivery of complementary therapy |

Cater to their needs Giving full attention Gave something no one else offered Able to hand them responsibility during session A special relationship Having close physical contact See the person not the disease Talking about concerns beyond illness Atmosphere of centre important Stigma in attending With therapist with knowledge about advance disease patients needs Waiting for session/not wanting it to stop Being offered/able to choose treatments important |

Experience during complementary therapy

Well-being

The theme of well-being reflected an individual’s sense of psychological and physical health and how it altered during complementary therapy. In all five studies, the effect complementary therapy had on the participants’ well-being was discussed. Overwhelmingly, all participants found complementary therapy had a positive effect on them and there were no negative reports about its effects. A common finding was that participants found complementary therapy relaxing and calming. It left participants feeling healthier with reduced physical symptoms and negative thoughts:

It helped me to relax and decreased the pain and that helped me to sleep … I think that it was probably relieving the pain but also … relieving some of the anxiety that I experienced. (Massage: 33: p. 1208)

In four studies,31–34 complementary therapy also gave the participants a feeling of being empowered with descriptions such as feeling whole, special and important. It allowed them to feel dignified and good within themselves:

I feel like I am of some worth … that someone cares for me. It feels good because … I feel important somehow. (Massage: 32: p. 182)

Escapism/living in the moment

This theme referred to participants’ feeling of escaping their everyday reality of their disease or by being fully present so that they were not anxious about the future; this was found in three of the studies.31,33,35 Participants described feeling free from disease and worry, and complementary therapy creating a space for them to have some respite. Sometimes this was in a new or different space or time. In two studies,31,33 participants described the transcendence effects of the complementary therapy as it altered or halted time:

It felt like a timeless state, it was just there and then and time lost its meaning. (Massage: 33: p. 1208)

In three studies,31,33,35 participants described it as a sense of floating away and an awakening:

It has helped me relax. After my treatment I feel I am walking on air … as if I was floating away. (Massage: 33: p. 1205)

I can say that I wake up … when I’ve gotten that massage, I kind of wake up to a new day so to say. (Massage: 31: p. 544)

Participants stated that the complementary therapy allowed them to live in the present moment, which relieved them of their anxiety about their situation; their disease and the future. Overall, complementary therapy created a feeling of inner peace and escapism from their disease:

Well, I disconnect everything, it feels as it follows almost up to the head. I am completely gone from here. I think it is great. It is just wonderful. All gone as I lay here. (Massage: 32: p. 182)

Beyond the complementary therapy session

Lasting benefits

Three studies31,34,35 specifically discussed the ways in which participants’ lives were benefitted after the session(s) had finished. Participants described feeling ‘good’ afterwards and said it helped them cope with their disease and its impacts. It also created positive memories, a hope for the future and something to look forward to:

I feel really good for several days after … (Massage: 31: p. 543)

I felt satisfied and happy afterwards even if the circumstances in which I am in do not usually have the effect on me … but it (the massage) helped me somehow to manage the days in a good way. (Massage: 33: p. 1208)

One participant described it as offering something that they could depend on.

I must admit, at one stage I looked on it as a lifeline … (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 502)

Overall evaluation

In all five studies, participants discussed their overall evaluation of complementary therapy. Many participants struggled to put into words their experiences of complementary therapy and what they valued about it:

I felt more composed somehow, it’s difficult to explain… but I felt strengthened in some way. (Massage: 33: p. 1208)

I don’t quite know how to express myself … but I feel like I have gotten some strength and balance. (Massage: 32: p. 182)

However, all agreed it was a positive experience that gave them pleasure. Overall, they were satisfied with the therapy and felt it was a luxurious experience. One participant described it as a reward for enduring the illness:

that I would die during exactly such a moment because it’s so pleasant. (Massage: 31: p. 544)

I think it is luxury … (Massage: 32: p. 183)

Process of complementary therapy delivery in palliative care

Value of the therapist

A common theme in all five studies was the distinct value of the therapist for the participants. A large part of the benefit participants got from the therapist was the opportunity to talk to them. Participants valued discussing their concerns beyond their disease and to someone outside of their family. This talking reduced tension. Some participants who were reluctant to attend counselling, found relief in talking to the complementary therapist:

I wouldn’t admit I needed help, people kept saying to me to go for counselling, I said I don’t need help, I can cope with this on my own. I think that’s why I grabbed at the aromatherapy, because it wasn’t somebody counselling me, it wasn’t somebody asking me to open up. (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 500)

She’s [the aromatherapist] a part of the therapy, ‘cause she’ll listen to you … like a safety valve, she can let you give off steam or rant and rave’ (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 499)

Participants felt the therapist could see them as a person and not just a disease. By engaging with the therapist and spending time with them, participants felt it alleviated their feelings of loneliness. This relationship was key for participants to benefit from complementary therapy and without it some patients did not want to receive treatment:

It was important that it was someone I empathized with from the very beginning as I would not accept to get massage from just anyone. (Massage: 33: p. 1207)

Participants felt people may not want to touch them because of their condition and, therefore, the physical contact in itself gave the participants a sense of security:

The security in knowing that someone dares touching me too … without me having to ask for it. (Massage: 31: p. 543)

The complementary therapist took time for the participants and gave them caring attention. Participants felt they were almost handing over responsibility to the therapist as well as the therapist giving something of themselves to them suggesting a reciprocal relationship:

I had such a lot on my mind…(the reflexologist) was so very helpful and caring. (Reflexology: 35: p. 41)

It was more than just a massage it had to do with one person (the therapist) giving of herself. (Massage: 33: p. 1207)

Delivery of complementary therapy

Across all the studies, participants discussed how they would like the complementary therapy delivered and barriers they faced to receiving the therapy. Participants described a wish for longer and more frequent sessions. Some participants had to travel far to receive the therapy and disliked having to wait for the therapy.

(I disliked) the fact I had to wait for an appointment and couldn’t be fitted in some weeks … just wish more sessions were available. (Reflexology: 35: p. 41)

However, they appreciated that resources were stretched and felt privileged in having any therapy at all. Participants also suggested that the therapeutic impact of complementary therapy worked in a cumulative way and therefore more sessions would be beneficial.

Participants also highlighted the importance of receiving the therapy in a friendly environment in which they felt safe, such as a hospice or at home, with a therapist who had great knowledge of the therapy they were delivering and experience of providing therapy to people who had cancer. For these reasons, participants said they were unlikely to seek complementary therapy privately, as other therapists may not know much about cancer or have experience with seeing their cancer-related scars:

Personally speaking, because I have had breast cancer and this is a hospital environment, I feel happier here. I feel if I go somewhere else people will be looking at me. (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 501)

In four studies,31,32,34,35 participants contrasted the complementary therapy with conventional cancer treatments. Participants enjoyed being able to choose whether they had complementary therapy or not, as opposed to conventional treatment which they felt compelled to have. Compared to clinicians often discussing future treatment, the complementary therapy therapist offered something in the here and now with lots of details and choice to choose from (e.g. where they would like to be massaged and what oils to use):

She always treats you as you were there and not what you have been in the past or what she thinks is going to happen. (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 501)

Yes, it’s supportive, with my disease. As for the rest of the nursing staff it’s mostly about medicines and such … and with the masseur it’s a different kind of support … (Massage: 31: p. 543)

Although participants in the Cronfalk et al.33 study did not specifically compare complementary therapy with conventional treatments, they did state they felt it could be a valuable alternative to medication that aided in reducing anxiety and increasing sleep.

In one study, participants discussed the ‘stigma’ that surrounds complementary therapy both from their own and others’ preconceived ideas.34 Before developing cancer, many had not considered complementary therapy. Participants felt a need to justify having the complementary therapy and often concealed this from their GPs, family and colleagues due to a fear of judgement. One participant described how they lied to work about where they were going. Furthermore, one male described how complementary therapy might be seen as just for females. To begin with, participants themselves felt unsure about complementary therapy and were somewhat reluctant to try:

In the beginning I thought this [aromatherapy] would be a waste of time. I was very half-hearted, but after the first or second time … (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 502)

Now with me being a man … and me saying to my mates that I am going for aromatherapy, that’s only for women, you know what I mean. Prior to having aromatherapy I would have said it was cissy. (Aromatherapy: 34: p. 502)

Discussion

This thematic synthesis of five primary qualitative studies identified three analytical themes regarding how people with advanced cancer and in palliative care experience aromatherapy, reflexology and massage and how they would like these delivered. The three themes were related to the positive experiences during therapy, the lasting benefits after therapy, and the process of complementary therapy delivery in a palliative care population. Participants felt complementary therapy enhanced their physical and psychological well-being as well as providing an escape from their disease and related worries. Participants related that these benefits could last beyond the complementary therapy session, and that they gave them a sense of hope for the future. Participants reported that the value of the therapist was a key benefit of the complementary therapy. Participants also conveyed disappointment at the relative lack of resources. Each theme was represented in data from at least three out of five included studies, which demonstrates a commonality of findings across the body of work.

Overall, the participants felt complementary therapy had a positive effect on their psychological and physical symptoms with no perceived harm or negative consequences. Many participants found it hard to verbalize how complementary therapy made them feel, but reported feeling empowered and dignified during the session. Furthermore, participants felt relaxed with less pain and an increased ability to sleep. Overall, effectiveness studies have failed to find any strong links between complementary therapy and outcomes such as quality of life, anxiety and pain.37 However, the findings here indicate that one benefit of complementary therapy appears to be a perceived improvement in physical and psychological well-being, which highlights a gap between the findings from previously published quantitative data and qualitative research.

Complementary therapy provided an escape from the disease and worries allowing people to find some respite from the concerns of daily life. Participants described the transcendence benefits of the complementary therapy as it altered or halted time for them. Furthermore, the long-term benefits included providing a hope for the future. These experiences are clearly important; however, they are outcomes that effectiveness studies may have failed to capture. Indeed, previous literature has shown quantitative research often fails to capture participants’ experiences in its development.38 Researchers may not understand how participants experience complementary therapy and even the participants themselves often found it difficult to articulate the effect it had on them. The more unusual experiences such as the sense of floating away or of time standing still may be difficult, and perhaps not possible, to capture in standardized outcome measures. Certainly within palliative care research, there appears to be no quality of life scale that captures all of the domains considered important to palliative patients.39

Developing a relationship with the therapist helped patients feel comfortable with the complementary therapy and was one of the reasons they kept returning to have treatment. Many participants felt able to open up to the therapist in ways in which they could not do with members of their family. Within psychotherapy research, therapist effects have shown to account for up to 55% of the effect of the therapy40 with the simple act of talking having a positive effect on people’s mental health.41 Furthermore, within the cancer literature, social interaction has been shown to influence survival rates,42 which highlights how powerful social interactions, for instance with the therapists, can be.

Participants described complementary therapy working in a cumulative way and regular sessions were important to them; a dose response effect of some complementary therapies, such as music therapy, has been demonstrated43 but not yet in aromatherapy, reflexology or massage. Knowing the specific, or at least the minimal number and duration of sessions to make a positive impact on wellbeing is key to provision. Further trials should be guided by participants’ views in developing the intervention schedule.44 Compared to conventional treatment, participants felt more in control of their complementary therapy as it was something they chose to have and they enjoyed picking different oils and locations to be massaged; this sense of control has also been found in cancer patients.25

A negative experience relating to undergoing complementary therapy was revealed in one study, in which participants described a certain stigma (i.e. a feeling of shame) about receiving complementary therapy from friends, family and colleagues.34 Participants also felt they had their own misconceptions in regards to feeling unsure about complementary therapy before it began and were sometimes reluctant to try it. This issue was from a study published in Dunwoody et al.,34 and was not replicated in more recent papers; therefore, it is possible it is now outdated and stigma surrounding complementary therapy has reduced. Future research should consider exploring whether this stigma is still present and, if so, ways to reduce it.

This review is the first, to our knowledge, that has explored the experiences of complementary therapy from the view point of people with advanced cancer. Using a thematic synthesis, we were able merge rich data from small scale studies to explore common themes. There have been reviews of qualitative studies on the perspectives of other populations about complementary therapy. Most notably a previous review was undertaken in a population of people with cancer, irrespective of disease stage, and covering a broader range of complementary therapies.25 The overall results of this review were similar to our findings; the synthesis revealed that complementary therapy provided people with a sense of physical and psychological well-being, and gave them a special connection with the therapist. In addition, however, our review found evidence that complementary therapy allows people with advanced cancer to escape from their daily worries and has provided some key guidance about how they would like complementary therapy to be delivered.

Review limitations

This thematic synthesis has followed systematic methods to try to ensure all relevant peer reviewed articles were located. However, it is possible there was relevant grey literature not identified by our search strategy, which may have been informative to this synthesis. This review found only five studies and in two studies, the main author of the paper delivered the complementary therapy, which may have influenced the results.45 Nonetheless, the themes identified were reflected in nearly all of the five studies.

The five studies were conducted in the United Kingdom and Sweden and therefore may not be representative of the experiences of people from other countries where complementary therapy provision may differ. Although this review sought to explore the experiences of all people in palliative care regardless of diagnosis, all participants had advanced cancer. Furthermore, in one study, participants were massaged and interviewed within an oncology setting rather than a specific palliative care setting.32 Therefore, caution should be made in generalizing the findings to all palliative care settings and other palliative care patients and future research should explore how people with different illnesses experience complementary therapy.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

People with advanced cancer and receiving palliative care perceive aromatherapy, massage and reflexology to give them many benefits. Although the effectiveness evidence may not show strong evidence of benefit or harm, qualitative studies demonstrate people in palliative care find these treatments valuable and highlight many positive benefits that are not usually measured in clinical trials. Therefore, we think it is reasonable for these treatments to continue to be provided and for more robust research to be undertaken to further understand and evaluate the use of complementary therapy in palliative care.

Services should consider the way in which participants want complementary therapy to be delivered. Most importantly this should include where possible allowing participants the freedom to retain control about the type of complementary therapy they receive. The design of the intervention could include, for example, allowing patients to pick the location on the body of the massage. The therapist should continue to focus on building a good rapport and allow the person to speak freely if they so wish. The therapy needs to be conducted in a friendly environment in which the recipient feels safe. Future trials of complementary therapy in palliative should consider in development that the intervention is delivered in a way that reflects practice and patients’ wishes and consider what are the appropriate outcomes to measure that accurately reflect the aspects of the therapies that people in palliative care value.

Conclusion

This review of qualitative research identified that complementary therapy are perceived as beneficial by those with advanced cancer. Complementary therapy had a perceived impact on people’s well-being, by allowing them a time to get respite and escape from their disease and associated worries. Building a supportive relationship with the therapist was an integral part of the complementary therapy experience and should be driven to allow people in palliative care to be in control of their treatment. Although the evidence from effectiveness trials may be equivocal, we recommend that aromatherapy, massage and reflexology continue to be provided in palliative care as part of a holistic approach to care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 846440_supp_mat for Aromatherapy, massage and reflexology: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the perspectives from people with palliative care needs by Megan Armstrong, Kate Flemming, Nuriye Kupeli, Patrick Stone, Susie Wilkinson and Bridget Candy in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our service representatives, Judy Booth and Jill Preston, and lay representatives, Rose Amey and Veronica Maclean, for their involvement and support with this project.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Megan Armstrong’s post is supported by Marie Curie (grant number MCRGS-07-16-36). Paddy Stone’s post is supported by Marie Curie Chair’s grant (509537). Bridget Candy’s post is supported by Marie Curie core grant funding, grant (MCCC-FCO-16-U). Nuriye Kupeli post is supported by Alzheimer’s Society Junior Fellowship grant (grant award number: 399 AS-JF-17b-016).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs: Megan Armstrong  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6773-9393

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6773-9393

Nuriye Kupeli  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6511-412X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6511-412X

Bridget Candy  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9935-7840

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9935-7840

References

- 1. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12(2): 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Traeger L, Greer JA, Fernandez-Robles C, et al. Evidence-based treatment of anxiety in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(11): 1197–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Part A, Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. London: NICE, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Mahrezi A, Al-Mandhari Z. Palliative care: time for action. Oman Med J 2016; 31(3): 161–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, et al. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008; 76(6): 909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atkin N, Vickerstaff V, Candy B. ‘Worried to death’: the assessment and management of anxiety in patients with advanced life-limiting disease, a national survey of palliative medicine physicians. BMC Palliat Care 2017; 16(1): 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shin ES, Seo KH, Lee SH, et al. Massage with or without aromatherapy for symptom relief in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 6: CD009873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tabatabaee A, Tafreshi MZ, Rassouli M, et al. Effect of therapeutic touch in patients with cancer: a literature review. Med Arch 2016; 70(2): 142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmid W, Rosland JH, von Hofacker S, et al. Patient’s and health care provider’s perspectives on music therapy in palliative care–an integrative review. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17(1): 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McConnell T, Porter S. Music therapy for palliative care: a realist review. Palliat Support Care 2017; 15(4): 454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McConnell T, Scott D, Porter S. Music therapy for end-of-life care: an updated systematic review. Palliat Med 2016; 30(9): 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lau CHY, Xinyin W, Chung VCH, et al. Acupuncture and related therapies for symptom management in palliative cancer care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2016; 95(9): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu X, Chung VC, Hui EP, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 16776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lian W-L, Pan MQ, Zhou DH, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for palliative care in cancer patients: a systematic review. Chin J Integr Med 2014; 20(2): 136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kyle G. Evaluating the effectiveness of aromatherapy in reducing levels of anxiety in palliative care patients: results of a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2006; 12(2): 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Rahbar MH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life outcomes: a reflexology trial with patients with advanced-stage breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012; 39(6): 568–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jane S-W, Chen S-L, Wilkie DJ, et al. Effects of massage on pain, mood status, relaxation, and sleep in Taiwanese patients with metastatic bone pain: a randomized clinical trial. Pain 2011; 152(10): 2432–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilcock A, Manderson C, Weller R, et al. Does aromatherapy massage benefit patients with cancer attending a specialist palliative care day centre. Palliat Med 2004; 18(4): 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeng YS, Wang C, Ward KE, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in hospice and palliative care: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 56(5): 781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health 2018; 46(4): 448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, et al. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther 2012; 11(3): 187–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Micke O, Bruns F, Glatzel M, et al. Predictive factors for the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in radiation oncology. Eur J Integr Med 2009; 1(1): 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Candy B, King M, Jones L, et al. Using qualitative synthesis to explore heterogeneity of complex interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langlois EV, Tuncalp O, Norris SL, et al. Qualitative evidence to improve guidelines and health decision-making. Bull World Health Organ 2018; 96(2): 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smithson J, Britten N, Paterson C, et al. The experience of using complementary therapies after a diagnosis of cancer: a qualitative synthesis. Health 2012; 16(1): 19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12(1): 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Noyes J, Lewin S. Supplemental guidance on selecting a method of qualitative evidence synthesis, and integrating qualitative evidence with Cochrane intervention reviews. In: Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions, version 1, 2011, https://study.sagepub.com/booth2e/student-resources/chapter-3/chapter-3-%E2%80%93-choosing-your-review-methods

- 29. Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000; 320(7226): 50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2009; 15(11): 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Billhult A, Dahlberg K. A meaningful relief from suffering experiences of massage in cancer care. Cancer Nurs 2001; 24(3): 180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cronfalk BS, Strang P, Ternestedt BM, et al. The existential experiences of receiving soft tissue massage in palliative home care-an intervention. Support Care Cancer 2009; 17(9): 1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunwoody L, Smyth A, Davidson R. Cancer patients’ experiences and evaluations of aromatherapy massage in palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2002; 8(10): 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gambles M, Crooke M, Wilkinson S. Evaluation of a hospice based reflexology service: a qualitative audit of patient perceptions. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2002; 6(1): 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cronfalk BS, Strang P, Ternestedt BM. Inner power, physical strength and existential well-being in daily life: relatives’ experiences of receiving soft tissue massage in palliative home care. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18(15): 2225–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Tesnjak I, et al. A randomized clinical trial of caregiver-delivered reflexology for symptom management during breast cancer treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 24: 670–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Candy B, Vickerstaff V, Jones L, et al. Description of complex interventions: analysis of changes in reporting in randomised trials since 2002. Trials 2018; 19(1): 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCaffrey N, Bradley S, Ratcliffe J, et al. What aspects of quality of life are important from palliative care patients’ perspectives? A systematic review of qualitative research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52(2): 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baldwin SA, Imel Z. Therapist effects: findings and methods. In: Lambert MJ. (ed.) Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change, 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013, pp. 258–297. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Serfaty M, Csipke E, Haworth D, et al. A talking control for use in evaluating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behav Res Ther 2011; 49(8): 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lienert J, Marcum CS, Finney J, et al. Social influence on 5-year survival in a longitudinal chemotherapy ward co-presence network. Netw Sci 2017; 5(3): 308–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gold C, Solli HP, Kruger V, et al. Dose–response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29(3): 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Voils CI, King HA, Maciejewski ML, et al. Approaches for informing optimal dose of behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med 2014; 48(3): 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs 2015; 18(2): 34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 846440_supp_mat for Aromatherapy, massage and reflexology: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the perspectives from people with palliative care needs by Megan Armstrong, Kate Flemming, Nuriye Kupeli, Patrick Stone, Susie Wilkinson and Bridget Candy in Palliative Medicine