Abstract

Objectives:

Community health centers (CHCs) historically have reported challenges obtaining specialty care for their patients, but recent policy changes, including Medicaid eligibility expansions under the Affordable Care Act, may have improved access to specialty care. The objective of this study was to assess current levels of difficulty accessing specialty care for CHC patients, by insurance-type, and to identify specific barriers and strategies CHCs are using to overcome these barriers.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional survey of medical directors at CHCs in 9 states and DC that expanded Medicaid administered during summer 2017.

Methods:

Surveys were administered to medical directors at 361 CHCs (response rate=55%) to assess difficulty accessing specialty care by insurance-type and identify the specialties most difficult to obtain new patient visits. The survey also elicited ratings of commonly reported barriers to obtaining specialty care and identified strategies used by CHCs to obtain specialty care for patients. Descriptive results are presented.

Results:

Nearly 60% of CHCs reported difficulty obtaining new patient specialty visits for their Medicaid patients, most often for orthopedists. Barriers to specialty care reported by CHCs included few specialists in Medicaid Managed Care Organization (MCO) networks accepting new patients (69.4%) and MCO administrative requirements for obtaining specialist consults (49.0%). To enhance access to specialists, CHCs reported entering into referral agreements, developing appointment reminder systems, and participating in data exchange and other community-based initiatives.

Conclusions:

Medicaid patients at CHCs face many barriers obtaining specialty care. Payment policies and network adequacy rules may need to be re-examined to address these challenges.

Précis:

In a survey of community health center medical directors in 9 Medicaid expansion states and DC, nearly 60% reported difficulty obtaining new specialist visits and multiple access barriers.

Community health centers (CHCs) in the United States provide a primary care safety net to 25 million low-income patients annually,1 many of whom have complex health and social needs. CHCs predominantly deliver primary care and historically have reported challenges referring their patients for specialty care.2 Following expansions to Medicaid eligibility in 32 states and the District of Columbia (DC), authorized by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), CHCs in many states are treating a greater proportion of Medicaid enrollees and fewer uninsured patients.3

Medicaid eligibility expansions may affect CHCs in a variety of ways. Treating more insured patients may increase CHCs’ revenues, enabling investments in technology and staff to promote access to specialty care.4 Additionally, specialists may be more likely to accept referrals from insured patients. Conversely, all CHC patients may face barriers to specialty care including shortages of specialists or their reluctance to accept Medicaid. While some states have reported improved specialty access for Medicaid enrollees in recent years,4 a federal report from 2014 found that more than 40% of specialists surveyed did not offer appointments to Medicaid-enrollees and the median wait-time for specialty visits was twice as long as that for primary care visits.5 Overall, evidence on the ACA’s impact on access to specialty care is limited, with mixed results.6–8

Given this new policy landscape, in which CHCs located in Medicaid expansion states are providing services to a larger number of Medicaid enrollees who may or may not be able to access needed specialty care, we sought to understand current challenges and strategies used by CHCs to obtain specialty care for their patients in Medicaid expansion states. We conducted a survey of all CHCs that receive grant funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in a sample of Medicaid expansion states to identify the specific specialties for which access problems were most acute, document the most common access barriers, and identify the strategies that CHCs are using to expand access to specialty care for their patients.

Methods

We surveyed medical directors at 361 CHCs in 9 Medicaid expansion states and DC during summer 2017 (response rate=54.6%). CHCs, a type of Federally Qualified Health Center, are nonprofit, community-focused primary care providers that are located in medically underserved areas and provide services to all patients, regardless of ability to pay.9 Most CHCs receive grant funding from HRSA. CHCs with and without federal funding collectively serve one in six Medicaid enrollees.10 The study sample included California, Colorado, DC, Illinois, Louisiana, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington (average state-level response rate=58.9%, range: 26.3% (New Jersey) to 78.6% (Minnesota)). The survey was fielded as part of a larger effort to describe the landscape of care integration activities involving CHCs, specialty practices, hospitals, and social service organizations in 12 states and DC. The study was approved by our organization’s Institutional Review Board.

The web-based survey was completed by the medical director or a designee at each CHC. The survey included items that solicited ratings of difficulty obtaining timely initial visits with specialists outside of CHCs, by payer, using a 5-point Likert-type response scale with the options of “very difficult,” “somewhat difficult,” “neither easy nor difficult,” “somewhat easy,” or “very easy.” “Timely access” was not explicitly defined because states often use different standards.11 Respondents reporting that it was “very difficult” or “somewhat difficult” were asked to report, by payer, the one specialty for which it was most difficult to obtain new patient visits. Respondents were provided a drop-down menu of 16 specialties and were given the option to write in a specialty not listed.

CHCs also responded to questions about 12 barriers to obtaining specialty care (not specific to payer), identified from both a review of the literature and discussions with about a dozen stakeholders during an earlier phase of the project.2,12–16 Survey respondents also answered 17 questions about strategies that might be used to obtain specialty care for patients (not specific to payer) related to alternative care delivery models (e.g., telemedicine), data sharing arrangements, and participation in activities that are likely to strengthen linkages with specialists. The items were measured using a 6-point Likert-type response scale with the options of “not applicable,” “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” or “always.” CHCs responding “not applicable” were not included in the results for that item. Based on the distribution of survey item responses, results are presented with responses dichotomized to often/always vs. never/rarely/sometimes (or, for some items, very difficult/somewhat difficult vs. neither easy nor difficult/somewhat easy/very easy).

Results

Difficulty obtaining new patient specialty visits reported by CHCs varied by insurance-type, with most respondents reporting difficulty for patients with no insurance (168 CHCs; 85.3%) or Medicaid (113 CHCs; 57.3%) and a lower share of respondents reporting difficulty for patients dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare (69 CHCs; 35.0%), Medicare only (47 CHCs; 23.9%), or private insurance (28 CHCs; 14.4%).

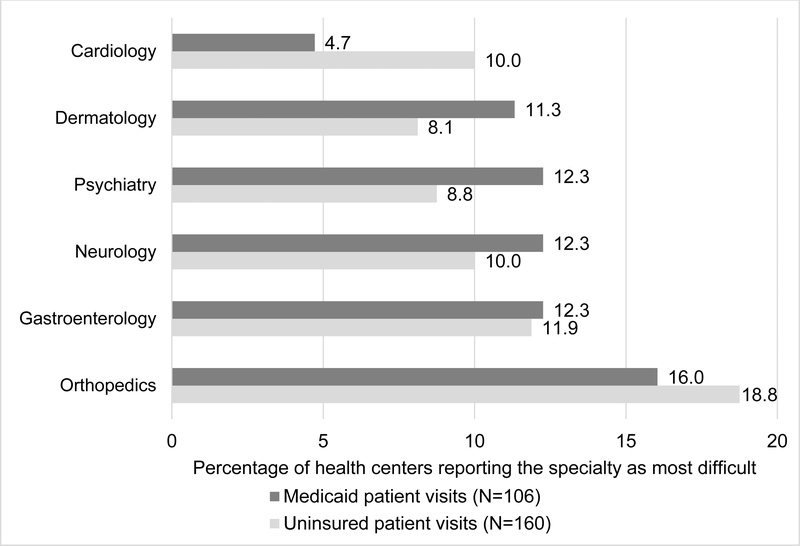

CHCs identified a range of specialties for which they had difficulty referring their Medicaid patients, with visits to orthopedists reported as the most challenging by 16% of respondents who reported difficulty (Figure 1). Other specialties with commonly reported access problems included gastroenterology (12%), neurology (12%), psychiatry (12%), dermatology (11%), and cardiology (5%). CHCs also reported the greatest access problems for these same six specialties for their uninsured patients.

Figure 1.

Specialties that were reported as the most difficult to obtain new patient visits among community health centers reporting difficulty for patients with Medicaid or no insurance

CHCs that reported difficulty obtaining specialty care for their Medicaid patients rated several barriers as often or always contributing to poor access. The most common barriers related to payment, coverage, and availability of appointments, including low Medicaid payment rates for specialists (78%), few specialists in Medicaid managed care organization (MCO) networks accepting new patients (69%), lack of Medicaid coverage for telemedicine (49%), and Medicaid MCOs’ administrative requirements for obtaining specialist consults (49%) (Table 1). More than half of respondents also rated geographic barriers and patients’ socioeconomic status as contributors to poor access, such as long distances or travel time required to reach specialists (60%) and patients’ out-of-pocket cost burden associated with specialty care (56%). More than one-third of CHCs reporting access problems cited difficulty establishing referral agreements with specialists (38%) and finding specialists that met the cultural or linguistic needs of their patients (38%).

Table 1.

Common barriers to and strategies for accessing specialty care for community health centers (CHCs) that report access problems for their Medicaid patients

| % | Total CHCs responding to item* | |

|---|---|---|

| Common barriers to specialty care | ||

| Payer factors | ||

| Low Medicaid specialist payment rates | 78.0 | 109 |

| Few specialists in Medicaid MCOs accept new patients | 69.4 | 108 |

| Medicaid MCO administrative requirements for obtaining specialist consults | 49.0 | 104 |

| Lack of Medicaid telemedicine coverage | 48.8 | 82 |

| Patient factors | ||

| Patient long travel distance/time to specialists | 59.8 | 112 |

| Patient out-of-pocket costs for specialty care | 56.3 | 112 |

| Few specialists meet cultural/language needs of patients | 37.5 | 112 |

| Provider relationships | ||

| Difficulty establishing formal referral agreements | 37.5 | 104 |

| Few personal relationships with specialists | 30.2 | 106 |

| Few affiliations with local hospitals/health systems | 24.1 | 108 |

| Regulatory factors | ||

| Difficulty expanding health center scope to include on-site specialty care | 31.2 | 93 |

| Difficulty obtaining malpractice insurance for specialists through the Federal Tort Claims Act | 15.1 | 73 |

| Common strategies to obtain specialty care | ||

| Alternative delivery models | ||

| On-site provision of specialty care for any patients in last 6 months | 84.1 | 113 |

| Use of e-consults for any patients in last 6 months** | 45.1 | 113 |

| Use of telemedicine for any patients in last 6 months** | 26.6 | 113 |

| Referral agreements | ||

| Has agreements with specialists about either types of referrals specialists will accept or information the health center will provide when making referrals | 64.6 | 113 |

| Has agreements with specialists about the type of information specialists will provide to the health center following visits | 41.6 | 113 |

| Has agreements with specialists about the types of patients to be referred | 18.6 | 113 |

| Has agreements with specialists about testing to be conducted prior to referrals | 17.7 | 113 |

| Has agreements with specialists about the timeframe by which specialists should send information to the health center following the specialist visit | 15.9 | 113 |

| Providing patient supports | ||

| Often or always makes appointments on behalf of patients | 61.1 | 113 |

| Often or always reminds patients about appointments | 39.8 | 113 |

| Data sharing | ||

| Often or always sends health information electronically to specialists | 43.4 | 113 |

| Often or always receives health information electronically from specialists | 28.3 | 113 |

| Often or always reads medical records of specialty practices | 13.3 | 113 |

| Community partnerships | ||

| Participated in health promotion initiatives with specialists in last 2 years | 65.8 | 111 |

| Participated in quality improvement projects with specialists in last 2 years | 56.8 | 111 |

Includes only health centers reporting difficulty obtaining new patient visits with specialists for their Medicaid patients. Denominators for barriers and strategies may differ due to item non-response and differences in the numbers of CHCs responding “not applicable” – which were excluded from the denominators.

E-consults refer to asynchronous electronic interactions between primary care and specialty care providers and telemedicine refers to real-time videoconferencing or “store-and-forward” applications in which digital content is transmitted to specialists for review at another time.

Note: MCO=Managed care organization.

CHCs reported difficulty with specialty referrals even though they deployed strategies that sought to improve access, either directly or indirectly (Table 1). Nearly two-thirds of CHCs reporting access problems had established agreements with specialists relating to the terms of referrals. Over 80% of CHCs reporting access problems provided at least some specialty care onsite, while nearly half reported using e-consults (45%) or telemedicine (29%) to interact with specialists. Most CHCs made specialist appointments on behalf of patients (61%), although fewer CHCs regularly reminded patients about upcoming appointments (40%). CHCs reported moderate levels of data sharing with specialists, including 43% who consistently shared health information electronically with specialists. By contrast, only 13% of CHCs were able to implement systems permitting real-time “read” access to the medical records of specialty practices. More than half of CHCs reported some form of collaboration with specialists, including participation in health promotion initiatives (66%) or quality improvement projects (57%) with local specialty practices.

Discussion

Consistent with past reports of significant access problems,2 85% of CHCs reported difficulty obtaining specialist visits for their uninsured patients. Despite the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid eligibility, which led nearly 12 million newly eligible adults across the US to gain Medicaid coverage,17 nearly 60% of CHCs in our sample of Medicaid expansion states reported difficulty obtaining new patient specialty visits for their Medicaid patients. While insurance expansions may facilitate access to specialty care by reducing some financial barriers to care, other barriers remain outside of CHCs’ control. In particular, the impact of insurance expansions will ultimately depend on the degree to which payment and delivery systems are aligned to ensure that patients gain access to appropriate and timely specialty care. The most current data available suggests that Medicaid pays only 70 percent of Medicare’s rates for specialty services,18 and these payment differentials are likely to persist as the federal share of funding for the expansion population decreases over time. Thus, specialists face strong disincentives to treat patients insured by Medicaid compared to other payers.

Most Medicaid enrollees in most states included in the study receive their insurance coverage via comprehensive Medicaid MCOs,19 which means both MCOs and the states play a large role in determining access to specialty care for the majority of Medicaid enrollees. CHCs in our study, in which 7 of 10 states had a Medicaid MCO penetration rate exceeding 70%,19 commonly reported narrow MCO networks as a challenge to obtaining specialty care for patients. Although the Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care Final Rule of 2016 required new, minimum standards for ensuring the adequacy of Medicaid MCO networks, it remains unclear whether states will define standards for individual specialties, go beyond time and distance standards to include appointment or office wait times, or begin to rigorously enforce the new standards.11 For sponsors and administrators of MCOs, our results suggest that Medicaid MCO networks in our sample of 9 states and DC may lack a sufficient number of specialists to care for Medicaid patients, which may reflect specialists’ reluctance to accept referrals for Medicaid patients. As such, administrators may want to consider reassessing both the number and type of specialists available for new patient visits and encouraging the use of strategies that can promote more efficient use of specialists.

CHCs reported difficulty accessing similar types of specialty care for both uninsured patients and Medicaid enrollees. Notably, substance use disorder (SUD) treatment specialists and dentists, whose services have historically been in high demand at CHCs, were rarely reported as the specialists that were most difficult to access through referrals, which others have speculated may be due to increased funding and attention for SUD treatment and Medicaid expansions, respectively.20,21

Among CHCs that reported specialty access problems, the majority had implemented strategies to obtain specialty care for their patients and help their patients make those appointments. To obtain specialty care for patients, most CHCs reported entering into agreements that specified the terms and expectations regarding referrals and engaging with specialty practices in health promotion and quality improvement initiatives, with fewer CHCs reporting use of e-consult systems and participation in data exchange with specialists. These findings highlight the range of strategies CHCs are pursuing, which are timely findings in light of HRSA’s August 2018 updated requirements that CHCs collaborate with specialists and document these efforts.22 Additionally, to promote patient attendance at appointments, many CHCs reported making appointments on behalf of patients, with fewer CHCs reporting use of reminder systems to help prevent their patients from being “no-shows” to their specialty appointments. Because evidence suggests that patient reminders via phone or text can help promote visit attendance,23 more CHCs should consider pursuing this strategy.

This cross-sectional survey did not include items about changes since Medicaid expansion and cannot make any casual conclusions about the impact of Medicaid expansion on changes in access to specialty care. Additional study limitations include non-response bias, which may have led us to either over- or understate actual levels of difficulty accessing specialty care. In addition, we may not have captured the full breadth of strategies CHCs are using to secure specialty care for their patients. Additionally, further research is needed to determine if these findings differ for CHCs in states that did not expand Medicaid. Finally, although our survey did not include all Medicaid expansion states, we designed the sample to be geographically diverse.

Conclusion

Obtaining specialty care is a significant problem for uninsured patients and Medicaid patients seeking care from CHCs, the entry point to the U.S. health care system for tens of millions of low-income patients. Despite using a wide range of strategies to achieve integrated systems of care with specialists in their communities, CHCs report few available specialists, low Medicaid payments, long travel times, and high cost-sharing burdens for patients as the greatest barriers to obtaining specialty care for their patients. Payment policies and network adequacy rules may need to be re-examined in order to reduce long-standing inequities in access to specialty care for our nation’s most vulnerable residents.

Take-Away Points:

Community health centers (CHCs) historically reported barriers to specialists for their patients. CHCs in 9 states and DC that expanded Medicaid eligibility reported challenges accessing specialty care for their patients, particularly for orthopedists, gastroenterologists, neurologists, and psychiatrists.

Barriers to specialty care reported by CHCs included few specialists in Medicaid Managed Care Organization (MCO) networks accepting new patients (69.4%) and MCO administrative requirements for obtaining specialist consults (49.0%).

In response to these and other challenges, CHCs are using a wide range of strategies to better integrate primary and specialty care services to provide more coordinated care to their patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work was supported through the RAND Center of Excellence on Health System Performance, which is funded through a cooperative agreement (1U19HS024067–01) between the RAND Corporation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content and opinions expressed in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Agency or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Contributor Information

Justin W. Timbie, RAND Washington

Ashley M. Kranz, RAND Washington, 1200 S Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202.

Ammarah Mahmud, RAND Washington

Cheryl L. Damberg, RAND Santa Monica

References

- 1.Health Resources and Services Administration. 2016. National health center data. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx Published February 21, 2018. Accessed May, 17, 2018.

- 2.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1459–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin P, Sharac J, Zur J, Rosenbaum S, Paradise J. Health center patient trends, enrollment activities, and service capacity: Recent experience in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/health-center-patient-trends-enrollment-activities-and-service-capacity-recent-experience-in-medicaid-expansion-and-non-expansion-states/ Published February 2015. Accessed February 21, 2018.

- 4.Artiga S, Rudowitz R, Tolbert J, Paradise J, Majerol M. Findings from the Field: Medicaid Delivery Systems and Access to Care in Four States in Year Three of the ACA. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/findings-from-the-field-medicaid-delivery-systems-and-access-to-care-in-four-states-in-year-three-of-the-aca/ Published September 20, 2016. Accessed October 12, 2018.

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. Access to care: Provider availability in Medicaid managed care. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-13-00670.pdf Published December 2014. Accessed October 12, 2018.

- 6.Biener AI, Zuvekas SH, Hill SC. Impact of recent Medicaid expansions on office‐based primary care and specialty care among the newly eligible. Health Serv Res. 2017. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6773.12793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs PD, Duchovny N, Lipton BJ. Changes in health status and care use after ACA expansions among the insured and uninsured. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1184–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alcalá HE, Roby DH, Grande DT, McKenna RM, Ortega AN. Insurance type and access to health care providers and appointments under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2018;56(2):186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Resources and Services Administration. HRSA health center program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/healthcenterfactsheet.pdf Published August 2018. Accessed October 12, 2018.

- 10.National Association of Community Health Centers. Community health center chartbook. http://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Chartbook2017.pdf Published June 2017. Accessed October 12, 2018.

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. State standards for access to care in Medicaid managed care. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-11-00320.pdf Published September 2014. Accessed April 2, 2018.

- 12.Felland L, Lechner AE, Sommers A. Improving access to specialty care for Medicaid patients: Policy issues and options. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2013/jun/improving-access-specialty-care-medicaid-patients-policy-issues Published June 6, 2013. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 13.Makaroun LK, Bowman C, Duan K, et al. Specialty care access in the safety net—the role of public hospitals and health systems. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):566–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Commonwealth Fund. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: Early insights. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2011/oct/electronic-consultations-between-primary-and-specialty-care Published October 19, 2011. Accessed October 13, 2018. [PubMed]

- 15.The Commonwealth Fund. Assessing and addressing legal barriers to the clinical integration of community health centers and other community providers. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2011/jul/assessing-and-addressing-legal-barriers-clinical-integration Published July 15, 2011. Accessed October 13, 2018.

- 16.Spatz ES, Phipps MS, Wang OJ, et al. Expanding the safety net of specialty care for the uninsured: a case study. Health Serv Res.. 2012;47(1pt2):344–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid expansion enrollment. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-expansion-enrollment/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D Published July 1, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- 18.Zuckerman S and Goin Dana. How much will Medicaid physician fees for primary care rise in 2013? Evidence from a 2012 survey of Medicaid physician fees. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8398.pdf Published December 2012. Accessed April 2, 2018.

- 19.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Managed Care Penetration Rates by Eligibility Group. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/managed-care-penetration-rates-by-eligibility-group/ Published July 1, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- 20.Baum N, Rheingans C, Udow-Phillips M. The impact of the ACA on community mental health and substance abuse services: Experience in 3 great lakes states. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation; Published August 2017. Accessed October 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasseh K, Vujicic M. The impact of the affordable care act’s Medicaid expansion on dental care use through 2016. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(4):290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Resources and Services Administration. Health center program compliance manual revisions. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/programrequirements/pdf/healthcentercompliancemanual-revisions.pdf Published August 20, 2018. Accessed Ocotber 13, 2018.

- 23.Perri-Moore S, Kapsandoy S, Doyon K, et al. Automated alerts and reminders targeting patients: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):953–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]