Abstract

Introduction:

This study investigated whether legalization of recreational marijuana sales and retail availability of marijuana in Oregon counties were associated with higher levels of marijuana use and related beliefs among adolescents.

Methods:

Biennial data for 6th, 8th and 11th graders from the 2010 to 2018 Student Wellness Survey (SWS) in 35 Oregon counties (N=247,403) were analyzed in 2019 to assess changes in past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs (e.g., perceived availability of marijuana) in counties that allowed recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas beginning in October 2015 compared to counties that did not. Analyses were also conducted with the 2016 and 2018 SWS data (n=101,419) to determine whether the association between allowing recreational marijuana sales and marijuana use could be accounted for by retail marijuana outlet density and beliefs.

Results:

Higher rates of past-30-day marijuana use and more favorable beliefs were observed in counties that allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas, both before and after legalization of recreational sales in 2015. The prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use increased, relative to the downward secular trend, after legalization both in counties that did and did not allow recreational marijuana sales. There were parallel changes in beliefs favorable to marijuana use. Analyses with 2016 and 2018 SWS data suggested that the association between allowing recreational marijuana sales and past-30-day marijuana use could be accounted for by retail marijuana outlet density and beliefs.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that legalization and greater retail availability of recreational marijuana is positively associated with marijuana use among adolescents.

Introduction

As of June 2019, recreational marijuana use is legal for adults at least 21 years old in 11 states and the District of Columbia, and recreational marijuana sales are legal in 10 states.1 Additional states have bills pending that would legalize adult recreational use. Liberalization of marijuana policies raises public health concerns, especially about its potential effects on marijuana use and adverse consequences among adolescents.2 Legalization of recreational marijuana may influence marijuana use among adolescents by increasing availability of marijuana and exposure to marijuana use by adults, encouraging social norms favorable to marijuana use, or reducing perceptions of harm.3,4

Research on the effects of state-level marijuana legalization for recreational sales and use has yielded mixed findings. A study based on data from the Healthy Kids Colorado Survey found no changes in the prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use among high school students after legalization of commercial recreational marijuana sales in 2014.5 In another study, legalization of recreational marijuana in Washington State was associated with decreases in use among 8th and 10th graders, but no changes in use among 12th graders.6 A report from the Oregon Health Authority showed slightly higher rates of past-30-day marijuana use from 2012 to 2018 among Oregon 8th and 11th graders compared to national estimates, but a small decrease in the prevalence of marijuana use among 8th and 11th graders over this time period.7 A small increase in the perceived ease of obtaining marijuana and a decrease in the perceived harm of marijuana use were found among 8th and 11th graders after legalization.

In states where recreational marijuana is legalized, cities or counties often may restrict or prohibit the operation of recreational marijuana producers, processors, wholesalers and retailers.5,8 Despite substantial variation in how recreational marijuana policies are implemented and enforced locally, limited research has addressed this issue. The study of high school students in Colorado found no significant differences in the changes in past-30-day marijuana use from 2013 to 2015 among youth living in cities or counties that allowed recreational marijuana sales in 2014 compared to cities or counties that did not.5 In another study, increases in marijuana use were observed post-legalization among adolescents in Oregon, but only among those who had used marijuana previously.9 Counter-intuitively, these increases were greater in communities that prohibited sales. The sample for this study, however, was relatively small (N = 444) and was drawn from only seven school districts.

This study investigates associations of county-level recreational marijuana sales policies for unincorporated areas and retail availability with changes in marijuana use and beliefs among adolescents in Oregon before and after legalization of retail sales in October 2015. This study also explores whether any such associations can be accounted for by differences in perceived availability, risk, and parental approval. Finally, the study investigates age-related differences in the association between retail marijuana availability and adolescent marijuana use. This study addresses important gaps in our knowledge about potential effects of local policies on marijuana use among adolescents and the mechanisms through which these policies may influence young people.

Study hypotheses are: (1) Retail availability of marijuana, prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs favorable to marijuana use will be higher in Oregon counties that allowed recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas after legalization; (2) The prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs favorable to marijuana use will increase to a greater extent after legalization in counties that allowed recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and have greater retail availability of marijuana; (3) The level of perceived risk of marijuana use will decrease to a greater extent in these counties after 2015; (4) The association between allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and marijuana use will be stronger among older adolescents, who are likely to have easier access to marijuana and greater exposure to peers or adults who use or approve of marijuana use; and (5) Observed relationships between county recreational marijuana sales policies in unincorporated areas and past-30-day marijuana use will be attenuated when controlling for retail outlet density and marijuana-related beliefs.

Method

Study Sample

This study used Student Wellness Survey (SWS) data collected in the spring of 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018 from cross-sectional samples of 6th, 8th and 11th graders in 174 school districts within 35 Oregon counties. The SWS is an anonymous self-administered survey sponsored by the Oregon Health Authority and the Oregon Department of Education.10 SWS response rates ranged from 67% to 77%. Of 286,670 students who participated in the SWS from 2010 to 2018, 220,930 (77%) provided complete data for all study variables. Because 9–10% of belief items were missing, we used the expectation maximization procedure in SPSS version 25 to impute values for these variables using student demographic characteristics, past-30-day marijuana use, and belief variables as predictors. This resulted in an analytic sample of 247,403 students (86.3%). Sensitivity analyses were conducted with and without imputed data to assess the robustness of the results.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation.

Measures

Marijuana use.

Students were asked how many times they used marijuana in the past 30 days, with six responses ranging from “0 times” to “40 or more times.” Because over 85% of students reported no marijuana use in the past 30 days, this measure was dichotomized (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Perceived availability of marijuana.

Students were asked, “If you wanted to get some marijuana, how easy would it be for you to get some?” with four response options (“Very hard,” “Sort of hard,” “Sort of easy,” and “Very easy”).

Perceived risk of using marijuana.

Students were asked, “How much do you think people risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways) if they try marijuana once or twice?” with four response options (“No risk,” “Slight risk,” “Moderate risk,” and “Great risk”).

Perceived parent approval of marijuana use.

Students were asked, “How wrong do your parents feel it would be for you to smoke marijuana?” with four response options (“Very wrong,” “Wrong,” “A little bit wrong,” and “Not wrong at all”).

Demographic characteristics.

Students were asked to report their age, grade level, sex (0 = male, 1 = female), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and race (0 = non-white, 1 = white). The race variable provided by the Oregon Health Authority was limited to white vs. non-white to maintain confidentiality.

Survey year.

Survey year was treated as a student-level variable and was coded 1–5. This measure was included to capture secular trends in marijuana use and beliefs. Two dummy variables representing 2016 and 2018 versus pre-legalization years were created to determine whether there were significant changes in the prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs after legalization of sales in October 2015.

County characteristics.

The Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC) oversees the distribution, sales and consumption of alcohol and marijuana in the state, and maintains information on state and local alcohol and marijuana regulatory policies. Using marijuana policy information from the OLCC,11 counties were classified as either allowing sales of marijuana for recreational use in unincorporated areas beginning in October 2015 or not. Because school district IDs were masked to maintain confidentiality, municipal policies regarding recreational marijuana sales could not be considered. Addresses for licensed retail establishments that sell marijuana for recreational and medical use were obtained from the OLCC in March, 2018.12 The numbers of licensed marijuana retail outlets reflect both county and city policies. There was a strong correlation between the number of licensed outlets in Oregon counties in 2016 and 2018 (r=0.99, p<.001); therefore we used 2018 outlet data in our analyses. Using data from the Oregon Department of Transportation, we computed the number of licensed recreational marijuana retail outlets per roadway mile as a measure of outlet density.13 Because of the skewed distribution, a variable was created representing low, medium and high levels of retail outlet density. Rural-urban continuum codes for 2017 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture were used to represent urbanicity of Oregon counties.14

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare counties that do and do not allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas. Multi-level regression analyses were conducted to examine changes in past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs in counties that allowed recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas beginning in October 2015 compared to counties that did not. Initial models included cross-level interaction terms (e.g., county recreational marijuana sales policy × student grade level). County and student-level demographic characteristics were included as covariates. To assess the explanatory value of retail marijuana availability and beliefs, we analyzed 2016 and 2018 SWS data (n=101,403) by first examining the relationship between county recreational marijuana sales policy and past-30-day marijuana use, controlling for county and student demographic characteristics. Marijuana retail outlet density and beliefs were added to subsequent models. These analyses were conducted in 2019 using HLM, version 7.03 to adjust for clustering of observations within counties and school districts.15 Sample weights were used in all analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Over half (20) of the 35 Oregon counties did not opt out of the state law and allowed legalized recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas beginning in October 2015 (Table 1). Of the 15 counties that do not allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas, 5 have at least one city or town that does. As expected, counties allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas had a significantly higher density of licensed retail outlets compared to counties that did not allow sales. Counties allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas were also more urban. On average, marijuana-related beliefs were similar across the two groups of counties. However, a higher percentage of students reported any past-30-day marijuana use in counties that allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas compared to students in counties that do not.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, mean (SD) or percent

| Variable | Total sample | Allows recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| County level | N = 35 | n = 20 | n = 15 |

| Retail marijuana outlet density (%)a | |||

| Low (0) | 33.3 | 5.0 | 68.8** |

| Medium (0.001 – 0.013) | 41.7 | 55.0 | 25.0 |

| High (0.014 – 0.058) | 25.0 | 40.0 | 6.3* |

| Rural-urban continuum codeb | 4.8 (2.6) | 3.6 (2.3) | 6.4 (2.0)** |

| Student level | N = 247,403 | n = 202,866 | n = 44,537 |

| 6th grade (%) | 32.9 | 32.9 | 33.2 |

| 8th grade (%) | 37.8 | 37.7 | 38.0 |

| 11th grade (%) | 29.3 | 29.4 | 28.9 |

| Age | 13.8 (2.0) | 13.8 (2.0) | 13.8 (2.0) |

| Female (%) | 50.7 | 50.7 | 50.6 |

| Hispanic (%) | 21.1 | 19.0 | 30.6 |

| White (%) | 68.8 | 69.8 | 64.4 |

| Past-30-day marijuana use (%) | 10.8 | 11.0 | 9.8* |

| Perceived availability of marijuanac | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.2) |

| Perceived risk of marijuana usec | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.0) |

| Perceived parent approval of marijuana usec | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

Retail marijuana outlet density is based on licensed marijuana outlet data obtained in March 2018.

Rural-urban continuum code values ranged from 1 (includes metro area with at least 1 million population) to 9 (completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population); thus, a lower value represents greater urbanicity.

Beliefs variables are coded on a four-point (1–4) scale with a higher value indicating a higher level of the belief.

Multi-level Analyses

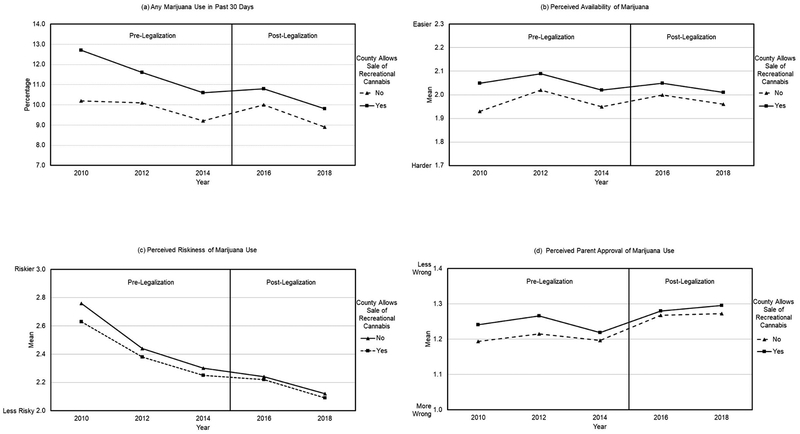

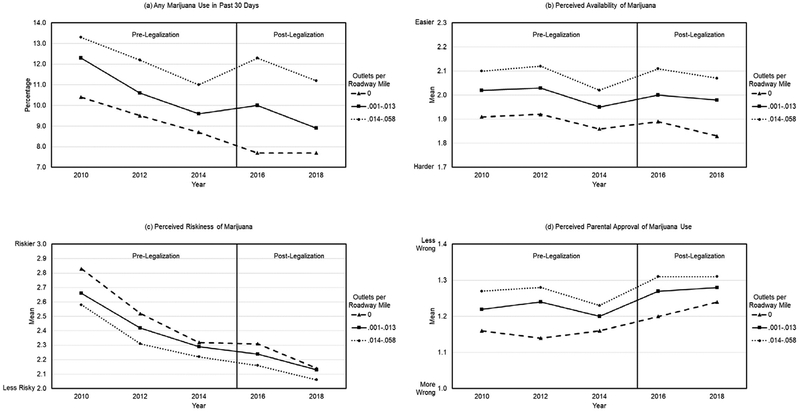

Initial multi-level logistic regression models predicting any past-30-day marijuana use and related beliefs included cross-level interaction terms (county recreational marijuana sales policy × pre-post legalization dummy variables). None of these interaction terms were statistically significant, indicating similar trends in past-30-day marijuana use and related beliefs from 2010 to 2016 and 2018 in counties that did and did not legalize recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas in 2015 (Figure 1) and across counties differing in retail outlet density (Appendix Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in (a) past-30-day marijuana use, (b) perceived availability of marijuana, (c) perceived risk of marijuana use, and (d) perceived parent approval of marijuana use by whether Oregon counties allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas since October 2015.

Results of subsequent multi-level logistic and linear regression models are in Table 2. Significant positive associations were found between living in counties allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and past-30-day marijuana use, perceived availability of marijuana, and perceived parent approval of marijuana use, and an inverse association with perceived risk of marijuana use, when controlling for student-level variables. The interaction between county recreational sales policy and grade level was statistically significant in all four models, indicating a stronger association between living in a county allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and past-30-day marijuana use and marijuana-related beliefs among 11th graders relative to 8th and 6th graders. Grade level and Hispanic ethnicity were positively associated with past-30-day marijuana use, perceived availability of marijuana, and perceived parent approval of marijuana use. Females perceived less availability of marijuana and less parent approval of marijuana use, but greater perceived risk. Survey year was inversely related to past-30-day marijuana use and marijuana-related beliefs. The 2016 and 2018 post- vs. pre-legalization dummy variables were positively related to past-30-day marijuana use and the three beliefs variables when controlling for the overall trend and student demographic characteristics, indicating higher levels of past-30-day marijuana use and more favorable marijuana beliefs after legalization in 2015 than would be expected given the secular trends. Analyses conducted without imputed values for the belief variables produced results very similar to those in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of multi-level regression analyses to assess county differences and changes in past-30-day marijuana use and related beliefs from 2010 to 2018

| Variable | Any past-30-day marijuana usea | Perceived availability of marijuanab | Perceived risk of trying marijuanab | Perceived parent approval of marijuana useb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County level | ||||

| Allows recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34)* | 0.16 (.03)** | −0.09 (.04)* | 0.05 (.01)** |

| Rural-urban continuum | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.004 (.006) | 0.007 (.006) | 0.003 (.002) |

| Student level | ||||

| Grade level | 2.94 (2.66, 3.33)** | 0.75 (.01)** | −0.32 (.01)** | 0.14 (.008)** |

| Female | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | −0.01 (.006)* | 0.04 (.006)** | −0.04 (.004)** |

| Hispanic | 1.46 (1.35, 1.59)** | 0.17 (.02)** | −0.07 (.02)** | 0.004 (.006) |

| White | 1.01 (0.91, 1.13) | 0.03 (.02) | −0.02 (.02) | 0.005 (.01) |

| Survey year | 0.88 (0.84, 0.93)** | −0.03 (.005)** | −0.19 (.006)** | −0.01 (.002)** |

| 2016 vs. pre-legalization | 1.20 (1.10, 1.31)** | 0.07 (.01)** | 0.16 (.01)** | 0.07 (.008)** |

| 2018 vs. pre-legalization | 1.19 (1.04, 1.36)* | 0.08 (.01)** | 0.25 (.02)** | 0.09 (.009)** |

| Cross-level | ||||

| Allows recreational marijuana sales × grade | 1.17 (1.02, 1.35)* | 0.07 (.01)** | −0.04 (.01)* | 0.06 (.01)** |

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)

Beta (standard error)

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Results of multi-level logistic regression analyses with 2016 and 2018 SWS data exploring whether the association between county recreational marijuana sales policies and adolescents’ marijuana use were attenuated after accounting for retail marijuana availability and marijuana-related beliefs are presented in Table 3. The likelihood of past-30-day marijuana use was significantly greater in counties allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas compared to counties not allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas when controlling for student demographic characteristics and survey year (Model 1). The association between allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and past-30-day marijuana use was attenuated and no longer statistically significant after including retail marijuana outlet density in the model, while retail outlet density was associated with a greater likelihood of past-30-day marijuana use (Model 2). Including marijuana beliefs in the model further attenuated relationships between county recreational marijuana sales policy, retail outlet density level, and past-30-day marijuana use, while all three belief variables were significantly associated with the likelihood of past-30-day marijuana use in the expected directions (Model 3). Survey year was inversely related to past-30-day marijuana use in all three models, indicating a decrease from 2016 to 2018. Results of analyses conducted without imputed values for belief variables were comparable to those in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of multi-level logistic regression analyses with county- and student-level predictors of past-30-day marijuana use in 2016 and 2018, odds ratio (95% confidence interval)

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| County level | |||

| Allows recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas | 1.19 (1.02, 1.38)* | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) |

| Retail marijuana outlet density level | --- | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41)** | 1.08 (1.00, 1.17)* |

| Rural-urban continuum | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) |

| Student level | |||

| Grade level | 3.50 (3.19, 3.83)** | 3.50 (3.19, 3.83)** | 1.38 (1.30, 1.47)** |

| Female | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16)* | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16)* | 1.15 (1.08, 1.23)* |

| Hispanic | 1.40 (1.30, 1.52)** | 1.40 (1.29, 1.52)** | 1.33 (1.26, 1.41)** |

| White | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) |

| Year | 0.87 (0.84, 0.91)** | 0.87 (0.84, 0.91)** | 0.87 (0.84, 0.91)** |

| Perceived availability of marijuana | --- | --- | 2.74 (2.64, 2.85)** |

| Perceived risk of trying marijuana | --- | --- | 0.56 (0.54, 0.58)** |

| Perceived parent approval of marijuana use | --- | --- | 1.93 (1.88, 1.99)** |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Discussion

This study investigated whether greater retail availability of recreational marijuana in Oregon counties was associated with increases in adolescent marijuana use and related beliefs after statewide legalization of recreational marijuana sales in October 2015. Findings indicate higher levels of past-30-day marijuana use, perceived availability of marijuana, and perceived parent approval of marijuana use, and lower levels of perceived risk of marijuana use among adolescents living in counties that allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas, both before and after legalization in 2015, compared to adolescents in other counties. Parallel trends in the prevalence of past-30-day marijuana use and related beliefs were observed from 2010 to 2018 among adolescents living in both counties that allowed and did not allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas. In both 2016 and 2018 there were significantly higher than expected levels of past-30-day marijuana use, perceived availability of marijuana, perceived parent approval of marijuana use, and perceived risk of marijuana use following legalization relative to the downward trends in years preceding legalization. The latter finding is in contrast to other studies finding decreases in perceived risk following decriminalization of marijuana or legalization of medical marijuana.16,17 Similar trends in past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs were observed for counties with low, medium and high levels of retail marijuana outlet density. Thus, the hypothesis that past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs favorable towards marijuana use would increase to a greater extent after legalization in Oregon counties with greater retail availability of marijuana was not supported. Overall, findings suggest that, relative to the downward trend from 2010 to 2014, there was a statewide increase in the prevalence of marijuana use among Oregon adolescents after legalization for recreational sales in 2015, and that greater retail availability of marijuana in counties that allow recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas is positively associated with both marijuana use and beliefs favorable towards marijuana use among adolescents.

The hypothesis that levels of past-30-day marijuana use and beliefs favorable towards marijuana use would be higher among adolescents in Oregon counties with greater retail availability of marijuana was supported. This relationship was stronger for 11th graders than younger adolescents. Analyses were also consistent with the hypothesis that the relationship between allowing recreational marijuana sales in unincorporated areas and past-30-day marijuana use would be accounted for by retail marijuana availability and beliefs favorable towards marijuana use. Adolescents living in Oregon counties and cities with greater retail availability of marijuana were more likely to perceive that marijuana would be easy to obtain, that their parents would approve of marijuana use, and that marijuana use was less risky. These findings suggest that differences in marijuana use between adolescents living in counties allowing sales of marijuana in unincorporated areas and those living in counties that did not are likely attributable to the broader normative climate. Recognizing that adolescents may not be able to easily obtain marijuana from licensed retail stores, it is also plausible that increased retail availability of marijuana may also contribute to greater availability of marijuana through diversion, as social sources are the primary way underage youth obtain other substances such as alcohol.18

Findings of this study should be considered in light of several limitations. Although the Student Wellness Survey is conducted in a large number of schools, it may not be representative of all adolescents in Oregon. Missing data may have biased our results, though we were able to impute missing data. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the findings were robust whether using imputed data or only cases with complete data. Social desirability and recall error are also potential sources of bias in self-report surveys. Although the study assessed trends in adolescent marijuana use and related beliefs in relation to marijuana policy changes in Oregon, the non-experimental study design limits the inferences that can be made regarding causal relationships. The cross-sectional survey design limited assessment of mediational mechanisms. Although highly correlated, recreational marijuana outlet data from 2018 may not have accurately represented retail recreational marijuana availability in 2016 because licensing of recreational marijuana outlets by OLCC did not occur until late 2016 with the retail market developing over time.

Additionally, because school district identifiers were masked, it was not possible to conduct analyses with data geocoded to the city level. Retail marijuana availability in the local community may be more important for adolescents’ marijuana use and beliefs than retail availability at the county level due to greater exposure to retail outlets and related advertising, greater marijuana use among adults in the community, and greater availability of marijuana from social sources. Future research should focus on the community-level or finer geographical units to better understand how local policies and retail availability may influence marijuana use and beliefs among youth.

Finally, further research is needed to determine whether and how local marijuana regulatory policies and related enforcement activities may affect marijuana availability, beliefs, and use among adolescents. For example, greater local restrictions on numbers of licensed marijuana retail outlets, hours of operation and advertising, and higher taxes on marijuana products may help to reduce both retail and social availability of marijuana.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA Grant Nos. R01 AA021726 and P60AA006282). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health. Drs. Paschall and Grube have received funding from the AB InBev Foundation to conduct an independent evaluation of the Global Smart Drinking Goals initiative. Dr. Grube has received other funding from the alcohol industry within the past three years, through the Responsible Retailing Forum, to develop and evaluate interventions to reduce alcohol sales to youth.

Appendix Figure 1.

Trends in (a) past-30-day marijuana use, (b) perceived availability of marijuana, (c) perceived risk of marijuana use, and (d) perceived parent approval of marijuana use by level of licensed marijuana retail outlet density (licensed retail outlets/roadway mile): low level = 0; medium level = 0.001–0.013; high level = 0.014–0.058.

References

- 1.National Conference of State Legislatures: State medical marijuana laws. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx Accessed August 19, 2019.

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flay BR, Schure MB. The theory of triadic influence In Wagenaar AC, Burris S, eds. Public Health Law Research, Theory and Methods. San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 2013;169–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks-Russell A, Ma M, Levinson AH, Kattari L, Kirchner T, Goodell EMA, Johnson RM. Adolescent marijuana use, marijuana-related perceptions, and use of other substances before and after initiation of retail marijuana sales in Colorado (2013–2015). Prev Sci 2019;20(2):185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilley JA, Richardson SM, Kilmer B, Pacula RL, Segawa MB, Cerdá M Prevalence of cannabis use in youths after legalization in Washington State. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173(2):192–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oregon Health Authority (2019). Youth marijuana use, attitudes and related behaviors in Oregon. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/MARIJUANA/Documents/fact-sheet-marijuana-youth.pdf Accessed June 14, 2019.

- 8.League of Oregon Cities. Local government regulation of marijuana in Oregon. http://www.orcities.org/Portals/17/Library/2018LocalRegulationofMarijuanAinOregon07-26-18.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 9.Rusby JC, Westling E, Crowley R, Light JM. Legalization of recreational marijuana and community sales policy in Oregon: Impact on adolescent willingness and intent to use, parent use, and adolescent use. Psychol Addict Behav 2017;32(1):84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Student Wellness Survey. Available at: https://oregon.pridesurveys.com/. Accessed on February 19, 2019

- 11.Oregon Liquor Control Commission. Record of Cities/Counties Prohibiting Licensed Recreational Marijuana Facilities. Available at: https://www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Documents/Cities_Counties_RMJOptOut.pdf Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 12.Oregon Liquor Control Commission. Active marijuana retail licenses approved as of 8/20/2018. Available at: https://www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Documents/Approved_Retail_Licenses.pdf Accessed on August 20, 2018.

- 13.Oregon Department of Transportation. 2016. Oregon Mileage Report. https://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/Data/Documents/OMR_2016.pdf Accessed June 30, 2019.

- 14.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/ Accessed June 30, 2019.

- 15.Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J, Patrick ME. Trends in use of marijuana and attitudes toward marijuana among youth before and after decriminalization: The case of California, 2007–2013. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26(4):336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Druss BG. The effect of medical marijuana laws on marijuana-related attitude and perception among US adolescents and young adults. Prev Sci 2018;20(2):215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Black CA, Ringwalt CL. Is commercial alcohol availability related to adolescent alcohol sources and alcohol use? Findings from a multi-level study. J Adolesc Health 2007;41(2):168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]