Abstract

Adolescent substance use is a major risk factor for negative outcomes including substance dependence later in life, criminal behavior, school problems, mental health disorders, injury and death. As it stands, there are a variety of available treatment approaches for adolescent substance use. In this publication we provide a user friendly, clinically focused, pragmatic review of currently used, evidence-based family treatments. Interventions reviewed include Multisystemic Therapy, Multidimensional Family Therapy, Functional Family Therapy, Brief Strategic Family Therapy, Ecologically Based Family Therapy, Family Behavior Therapy, Culturally Informed Flexible Family Treatment for Adolescents, and Strengths Oriented Family Therapy. The outcomes, treatment parameters, adolescent characteristics, and implementation factors are reviewed to help practitioners select the most appropriate treatment for adolescents in their or their agencies care.

Keywords: substance use, family therapy, externalizing problems, behavioral interventions, evidence-based treatment

Introduction

Adolescent substance use is a major risk factor for negative outcomes including substance dependence later in life, criminal behavior, school problems, mental health disorders, injury and death.1–8 Substance use is often comorbid with various psychiatric disorders, especially in clinical samples.9 While there is some evidence for the effectiveness of various interventions for child and adolescent substance use prevention10 and treatment11–17 continuing to develop, evaluate, and disseminate the most effective interventions will be essential to the welfare of adolescents. As it stands, there are a variety of available treatment approaches for adolescent substance use. Some focus on the treatment of individual adolescents through cognitive behavior therapy, motivation enhancement therapy, and supportive drug counseling. Others are structured to treat an adolescent peer group using group therapy. Family therapies have a long history in the treatment of adolescent substance abuse and as a group, family-based treatments have been found to be highly effective at reducing substance use.13,18

In this publication we intend to provide a user friendly, clinically focused, pragmatic review of currently used, evidence-based family treatments. More in-depth comparisons of the evidence for each family-based treatment are available.11,16–18 We will briefly review the theoretical background and empirical support for each family therapy, while offering descriptions of therapeutic techniques to illustrate how the treatment works in day-to-day treatment. We will also review various aspects of each treatment such as targeted population demographics, severity of population, location of service delivery, and the extent to which the various family-based treatments are ready for dissemination and implementation. By doing so we hope that readers will be able to assess which treatments would be effective for adolescents in their care or their agency’s care. It is important to note that emphasis will be placed on treatments that are most ready to be used in community settings, but we will also describe other treatments that are less researched.

Why Family-based Approaches?

Evidence and theory support a focus on family based approaches to adolescent substance use treatment. A recent meta-analysis by Tanner Smith and colleagues13 revealed that family therapy programs were more effective than several other approaches to which they were compared: behavioral therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, motivation enhancement therapy/motivational interviewing psychoeducational therapy, group counseling and practice as usual. In this meta-analysis, the statistical significant mean effect size reported for these comparisons is .26, which could be equated to a reduction from 10 days of use in the past month to 6 days of use, almost a 40% reduction of days of drug use. Hence, family approaches achieved a reduction in drug use that was 40% larger on average than the comparison treatments.

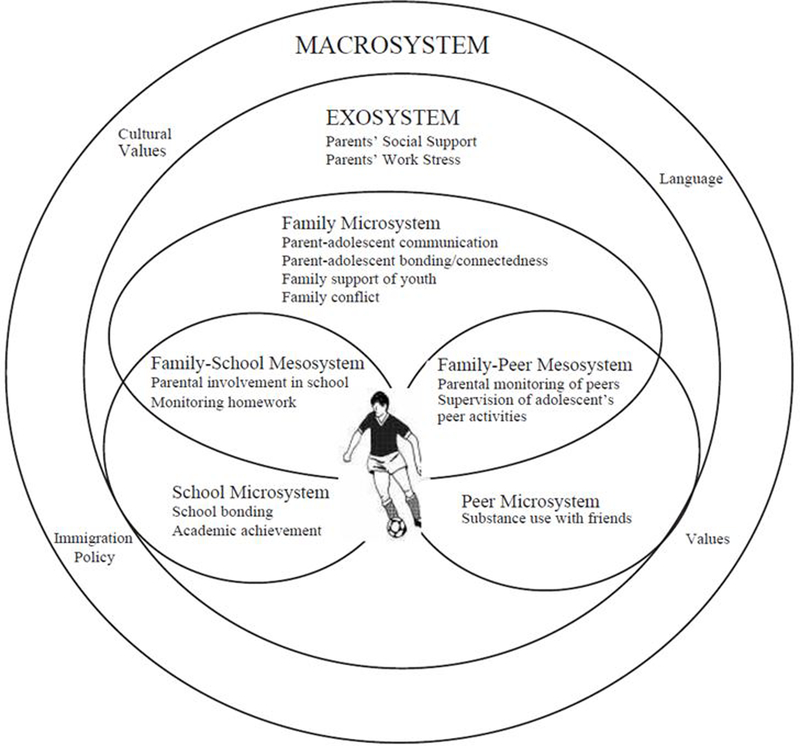

Theoretically, adolescents lie at the confluence of several social systems (e.g., school, community, peer), of which the family is central. As we have done in our prior work, we propose an ecodevelopmental systems theoretical approach that allows for more thorough description of the risk and protective factors predicting (i.e, creating risk or protection for) adolescent substance use (Figure 1).19–20 This theoretical approach, based on Bronfenbrenner’s integration of social ecological and life-span human development theories, assumes that children’s development is influenced by a number of interacting systems across time. It places the child first and most centrally in the developmental ecology of the family because of the foundational role that families play across child and adolescent development. While individual genetic, personality, and cognitive factors are important in understanding adolescent behavior, the ecodevelopmental approach knowingly emphasizes contextual factors over individual factors because of their well-established role as central risk and protective factors.21 Years of research have shown empirically that substance use and related problem behaviors are predicted by a large number of family based risk and protective factors:

Figure 1:

Ecodevelopmental Systems. Pantin, H., Schwartz, S. J., Sullivan, S., Coatsworth, J. D., & Szapocznik, J. (2003). Preventing Substance Abuse in Hispanic Immigrant Adolescents: An Ecodevelopmental, Parent-Centered Approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(4), 469–500. http://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303259355

Risk

Protective

Parental monitoring and knowledge30

Positive parent–teen affective quality31

Parent–teen communication32

Attachment to the family33

Opportunities for prosocial behaviors33

Anti-drug rules and norms34

Research has also indicated that family involvement in treatment more generally is a key factor in obtaining successful outcomes in the treatment of adolescent substance use.35

Thus, the ecodevelopmental theory and the research evidence strongly suggest that adolescent substance use is inextricably linked with the functioning of the family system. This indicates that family-based approaches may be especially effective because of their emphasis on changing the family environment. Family approaches typically target directly or indirectly each of the risk and protective factors enumerated above and focus on the relational interactions among family members. In this article, we will describe the ways in which the various family-based treatments presented here attempt to alter how families function as well as the families’ interactions with other systems within the adolescent’s ecology such as friends, school, neighborhood and extended family. We will begin by reviewing the treatments that are more advanced in the phases of implementation and will follow-up with newer or less tested interventions. Information was obtained on each treatment through published articles, chapters, and manuals and through online registries of evidence-based practices including Blueprints Programs, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices, and the National Institute of Justice’s Crime Solutions database.

Multi-systemic therapy

Multi-systemic Therapy (MST) is an evidence-based intervention that focuses on family and community engagement. Based in Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological framework, MST conceptualizes adolescent behavior as multi-determined and centered within multiple interacting systems. MST attempts to address problems within systems (family conflict, negative peer groups) and between systems (parent involvement in school work, peer group school attendance) to reduce the adolescents difficulties in school, the family and peer groups.36 A MST therapist does this by applying a variety of behavioral, cognitive behavioral and family systems approaches to strengthen families, support adolescents, and most importantly, to empower caregivers.

Phases of treatment

The sequence of therapy begins with the therapist’s efforts to align with the family to gain a clear understanding of the overarching goals and then they work to understand how the adolescent’s drug use fits within the social context. This is accomplished by getting background information on the multiple systems including a genogram, a strength and needs assessment, and a “fit circle” which visually displays what contextual factors are supporting the adolescent’s drug use. The therapist and family collaborate to prioritize which targets of change are most important and what interventions would be most effective. Central to these efforts are the use of a weekly supervision form which contains primary goals, previous intermediary goals, barriers, gains in treatment, an updated fit circle and new intermediary goals for the coming week. The interventions are implemented and obstacles to implementation are collaboratively overcome as they arise. Interventions might include helping parents implement rewards and punishments, asking families to communicate with each other in session, blocking harmful communication patterns, discussing marital conflict and providing alternatives, and assisting caregivers in increasing monitoring. Lastly, outcomes are assessed and if more work is needed, the therapist takes the new information and creates additional working hypotheses.36

MST has been modified into different adaptations which attempt to address specific problems such as child abuse, problem adolescent sexual behaviors and substance use. While the original MST showed effectiveness in reducing substance use,37 in an effort to focus on substance use when it is the primary difficulty, MST for substance abuse (MST-SA) was developed. This treatment integrates contingency management by offering vouchers and other incentives to youth who avoid drugs. In a randomized trial of MST and MST-SA in drug court setting, adolescents treated with MST-SA showed decreased drug use compared to traditional MST and drug court alone. As it stands, MST-SA is the version of MST that appears to best treat adolescent substance use problems.38

A primary difference from other evidence-based treatments in that it is delivered in a time intensive manner leading to an average of 60 direct service hours per family over a 4 to 6 month period.38

Functional Family Therapy

Functional Family Therapy39 is used for treating adolescent behavioral and psychological problems by improving communication between family members, increasing support, decreasing negativity, and altering dysfunctional family patterns. Through three phases of FFT treatment a therapist helps the family to increase their motivation, bring about changes in behavior, and help the family maintain changes.

Phases of Treatment

Phase 1: The therapist engages the family and enhances their motivation to change through reducing negativity and by emphasizing the problem behaviors as a family issue. Reframing is a common technique whereby negative attitudes or blame are validated by therapist and then reinterpreted in a more positive way. Thus when a mother is angry with her daughter for using substances and blames her for their family’s misfortunes, the therapist recognizes the anger and explains that those harsh feelings are likely stemming from the mothers love and concern for her daughter and the other family members.

Phase 2: The therapist makes efforts to bring about behavior change so that families can better perform tasks related to parenting, communication, and supervision. This is accomplished by assessing risk factors, evaluating relational patterns, encouraging active listening, promoting clear communication, helping parents implementing rules and consequences for negative behavior. One example might be parents who are taught to offer alternatives rather than ultimatums in their discussions with their adolescents, which will in turn reduce conflict.

Phase 3: Therapist focus on helping the family to maintain changes accomplished during therapy and to generalize those changes to new issues. This occurs as families are taught how to take new communication, problem solving, and parenting skills used to target specific behaviors into new situations. The therapist helps by linking new situations to successful navigation of previous situations. As the therapist reframes continued struggles as normal, the client families will be motivated to continue acting in adaptive ways rather than resorting to past behavior patterns.

The techniques in FFT are not based on step-by-step, one size fits all procedures, but allows for flexible, individualized treatment of families based on their unique relational and contextual factors. The theoretical foundation of FFT is systemic, behavioral and cognitive in nature. 39 It is described as protocol driven, but also involving an essential level of creativity at the hand of the therapist. Originally developed for treating externalizing behaviors more broadly, FFT has shown reductions in adolescent substance use in various clinical trials. FFT is also being tested for treating rural adolescents’ substance use problems through a video teleconference version.

Multi-dimensional Family Therapy

Multi-dimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) is a family-based treatment that makes use of individual therapy and multiple-systems approaches to treat adolescent substance use and other problematic behaviors.9 MDFT techniques target intrapersonal (i.e., feeling and thinking processes) and interpersonal factors that are leading the adolescent to act out in problematic ways. MDFT addresses problematic conditions and processes in the various domains of adolescent development including the individual, the parent(s), the family environment, and extra-familial systems.40 The family is the central context of adolescent development healthy functioning is theorized to be based on interdependent relating between parents and adolescents rather than emotional distance.41 Importantly, MDFT is understood not as a universally applied procedural approach, but rather as a flexible system of treatment that can adapt to individual circumstances.

Phases of treatment

The MDFT treatment course moves through three stages: “Build the Foundation,” “Prompt Action and Change by Working the Themes,” and “Seal the Changes and Exit.”

The first stage begins with an assessment of various risk and protective factors that the individual, parents, family and extra-family systems exhibit. The therapist crises and stress to increase motivation, collects information from various sources to set personally relevant goals, talks to all members of the family, and explains the MDFT process. The second phase involves therapeutic interventions that are designed to address risk factors and other impediments to healthy family functioning. The therapist actively listens and empathizes with the adolescent to increase their hope and encourages them to share their inner experience. Therapists also work with parents through psychoeducation and behavioral coaching with the aim to help them improve their parenting by strengthening their abilities to set limits, monitor, and support their child. New skills and perceptions are taught by the therapist who helps the family deal with problematic patterns of interaction that occur in-session. The extra-family systems are also engaged by the therapist so that parents and adolescents can have the additional support offered by community agencies.42

Multiple randomized clinical trials have shown the effectiveness of MDFT for reducing adolescent substance use in controlled, and community-based settings. There is also evidence that therapist adherence to the MDFT model improves substance use outcomes.43

Brief Strategic Family Therapy

Brief Strategic Family Therapy44–45 is an evidence-based integrative model, that that combines structural and strategic family therapy theory and intervention techniques to address systemic/relational (primarily family) interactions that are associated with adolescent substance use and related behavior problems. BSFT considers adolescent symptoms to be rooted in maladaptive family interactions such as inappropriate family alliances, overly rigid or overly permeable family boundaries, and parents’ tendency to believe that a single individual (usually the adolescent) is responsible for the family’s problems, These maladaptive patterns of family interactions may result in the symptoms, or merely prevent the family from effectively correcting the symptoms. Key characteristics of the intervention are that it is problem-focused, directive, and practical, and that it follows a prescribed format.

Interventions are organized into four domains, and are delivered in treatment phases to achieve specific goals at different times during treatment.46–47

Phases of treatment

Early sessions are characterized by joining interventions that are intended to establish a therapeutic alliance with each family member and with the family as a whole. The therapist joins the family by demonstrating acceptance of and respect toward each individual family member as well as the way in which the family as a whole is organized. Early sessions also include tracking and diagnostic enactment interventions. These interventions are designed to systematically identify family strengths and weaknesses and develop a treatment plan. The therapist encourages the family to behave as they would usually behave if the counselor were not present, by for example, asking them to speak with each other about the concerns that bring them to therapy, rather than directing comments to the therapist. From these observations, the therapist is able to diagnose both family strengths and problematic relations. Reframing interventions are used to reduce family conflict and create a sense of hope or possibility for positive change. Over the course of treatment, therapists are expected to continue to maintain an effective working relationship with family members (joining), facilitate within-family interactions (tracking and diagnostic enactment), and to directly address negative affect/beliefs and family interactions. As treatment progresses, the focus of treatment shifts to implementing restructuring strategies to transform family relations from problematic to effective and mutually supportive. Restructuring strategies include redirecting or blocking communication, assisting in the development of behavior management, helping families develop conflict resolution skills, and shifting family alliances and promoting parental leadership.

BSFT has been evaluated in a number of randomized clinical trials. Adherence to the BSFT intervention strategies by therapists has been linked to improved adolescent outcomes48 and a recent study demonstrated long term effects of the intervention on arrests, incarcerations and externalizing behaviors.49

Other Family Therapy Treatments

Ecological Based Family Therapy (EBFT) is a treatment that has been investigated in a few efficacy studies with runaway adolescents who use substances. It is based on Homebuilders Family Preservation model, which is an intervention created to keep youth in their own homes. EBFT is based on the assumption that most children are better off with their own families than in outside placements. Treatment begins by meeting first with the adolescent and the family members in individually so that they can be prepared to talk about the factors behind the runaway episode in a family session. At that point, the therapist assists the family in addressing these problems together with the goal of changing dysfunctional interactions. During treatment, the therapist uses an intrapersonal to interpersonal perspective in interpreting the adolescent’s problems by making use of questions and refames that focus on the family relationships.

Unlike some of the previous therapies, there is no underlying assumption in EBFT treatment that adolescent substance use stems directly from family dysfunction and conflict. As a result, the treatment occurs in both individual and family sessions allowing the therapist to help the youth make individual changes. This is accomplished through the use of cognitive behavioral techniques that teach the adolescent new skills for coping with intrapersonal and interpersonal problems.

Family Behavior Therapy is a family-based treatment with some initial efficacy in the treatment of adolescent substance use.50–51 The treatment involves the youth and at least one caregiver. The focus of the treatment is teaching families how to use behavioral techniques to improve family functioning. FBT is composed of four main components: behavioral contracting, stimulus control (identifying risky associations), urge control (coping skills), and communication skills training. The treatment argues that a strong relationship between the adolescent and their caregiver is central to dealing with the problem behaviors.52 As families successfully implement these strategies, it is expected that negative behaviors such as substance use and externalizing will decrease, while positive outcomes such as success in school and work will increase.

Culturally Informed & Flexible Family Treatment for Adolescents53 was originally developed to cater to Hispanic families. It recognizes that there are commonalities across ethnicities such as family conflict and clinical diagnoses, but that there are differences due to immigration, acculturation and cultural experiences. CIFFTA emphasizes the interaction between the family context and the wider cultural context as they create circumstances that lead to adolescent substance use. The flexible aspect of the treatment is based in a modular design that can be adjusted depending on adolescent, family and community characteristics. It also incorporates individual interventions such as Motivational Interviewing and other psycho-educational topics. There is some initial evidence of the efficacy of CIFFTA, including improvement over once a week traditional structural family therapy.54

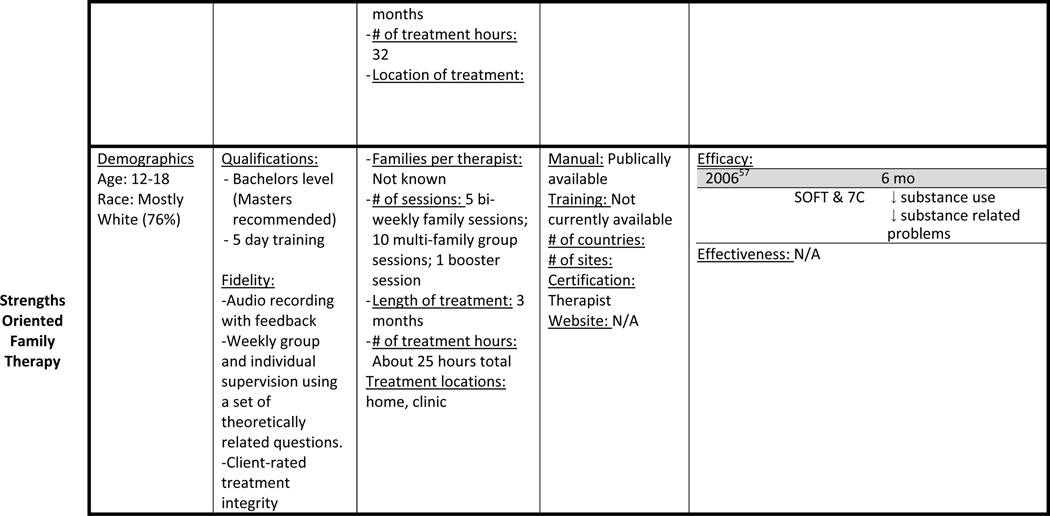

Strengths Oriented Family Therapy (SOFT)55–56 has some initial efficacy evidence in the treatment of adolescent substance use.57 Adolescents are seen in family and multi-family groups for about two hours each session. The treatment also includes some case management when deemed necessary. SOFT was specifically developed in an effort to build on previous family therapy treatments by adding motivational components, solution-focused terminology, and a strengths assessment. The emphasis on both youth and parent motivation shows the importance of the family context in adolescent substance use, while the strengths assessment attempts to leverage protective factors for the benefit of the youth. The initial efficacy trial found that SOFT and a group therapy treatment reduced adolescent substance use at a 6 month follow-up.

Selecting a treatment

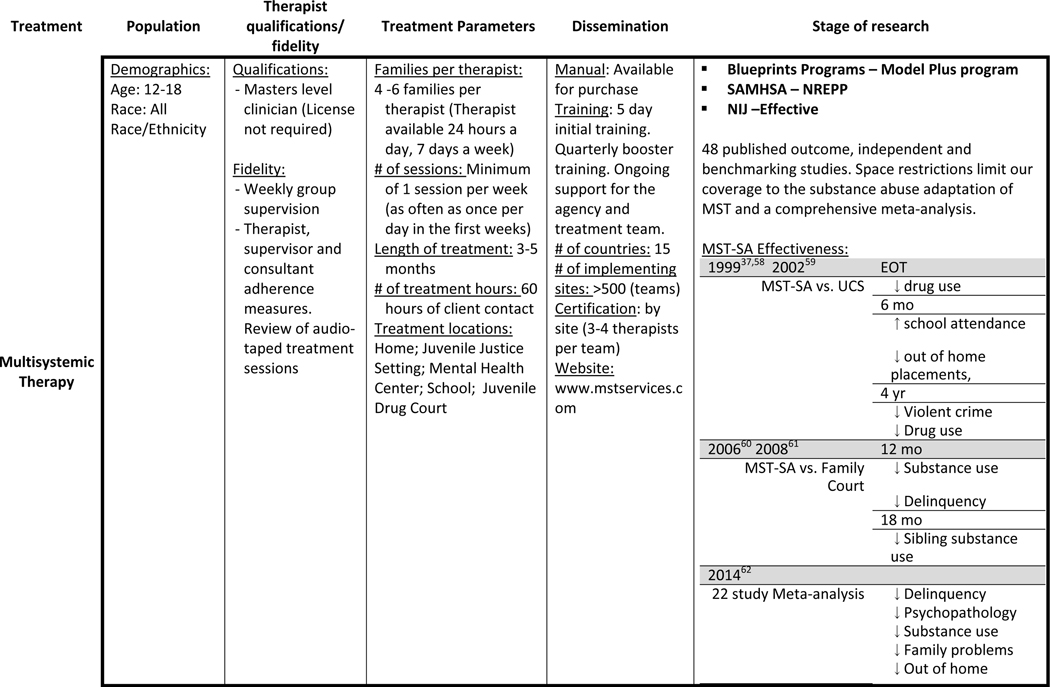

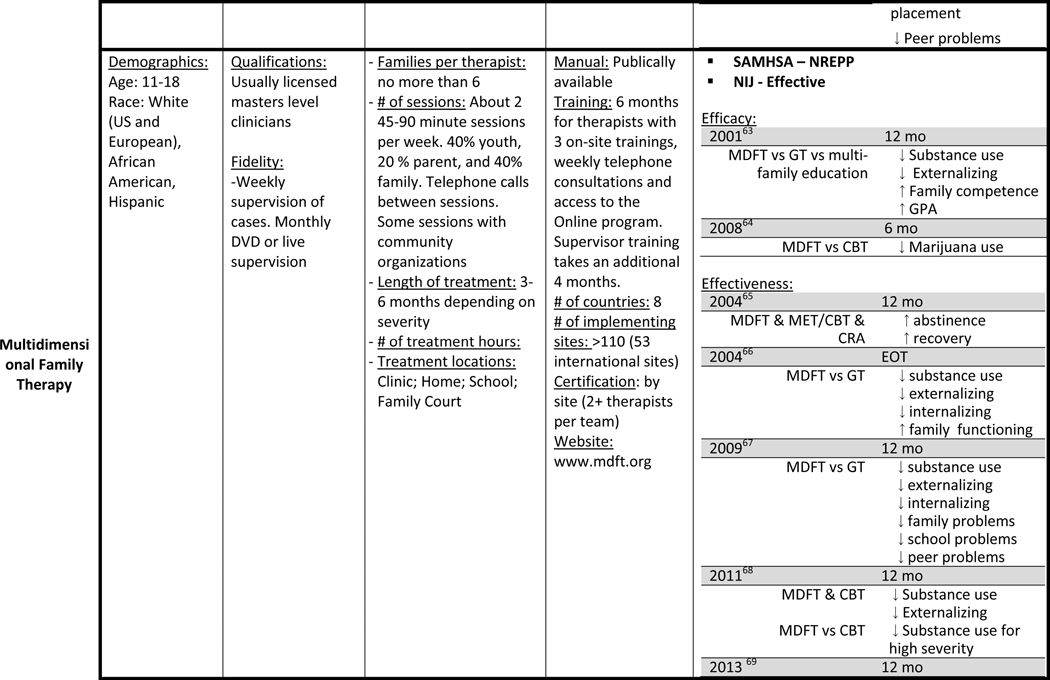

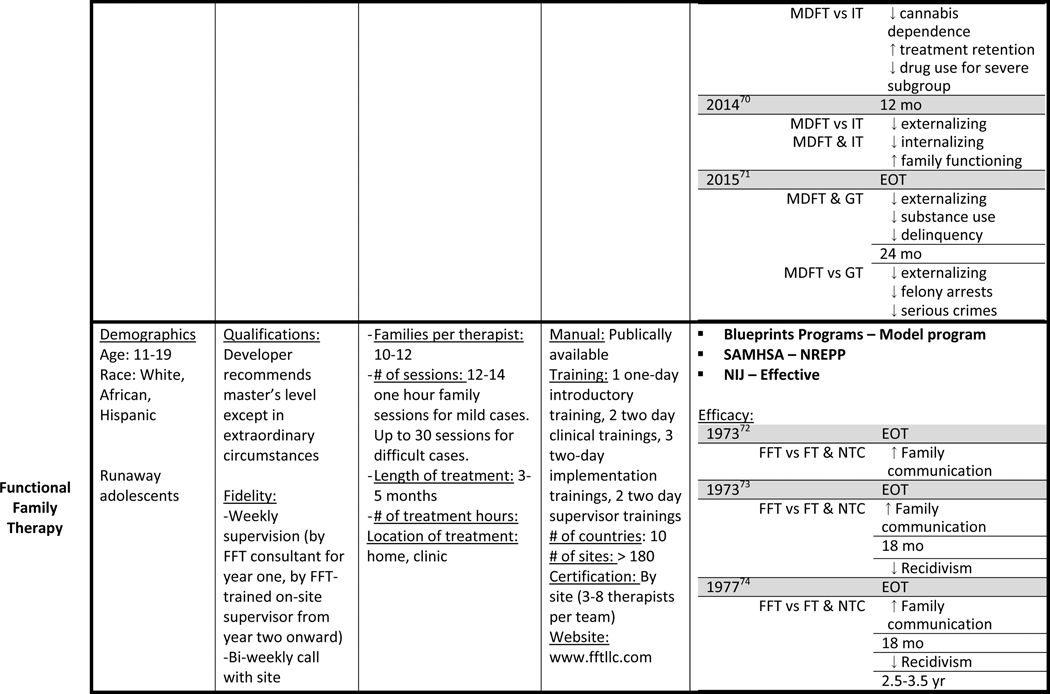

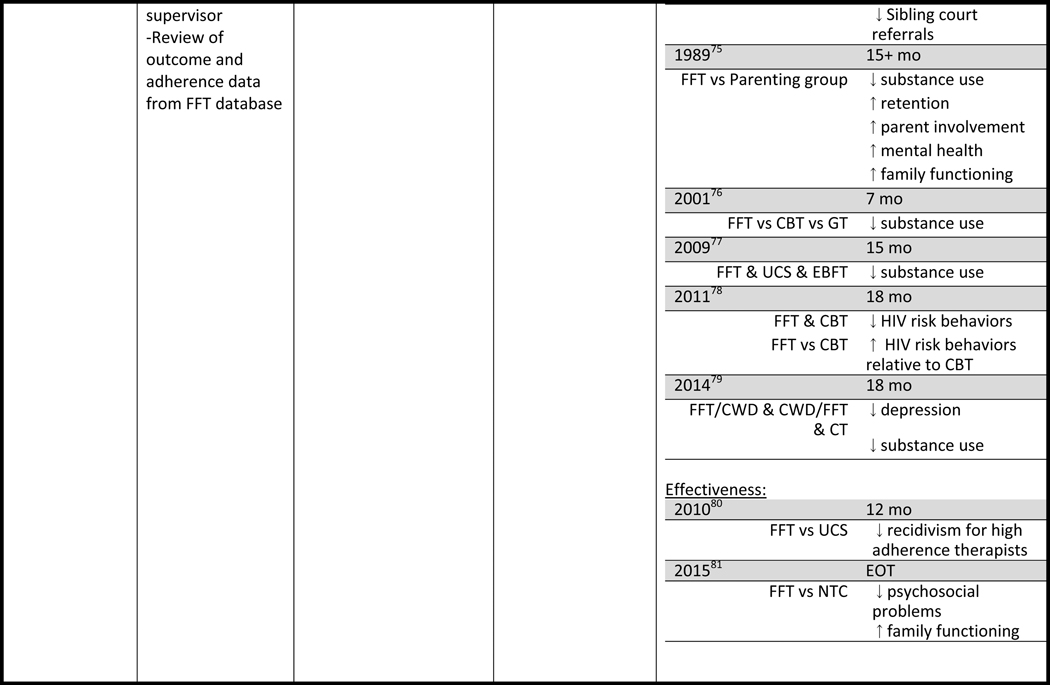

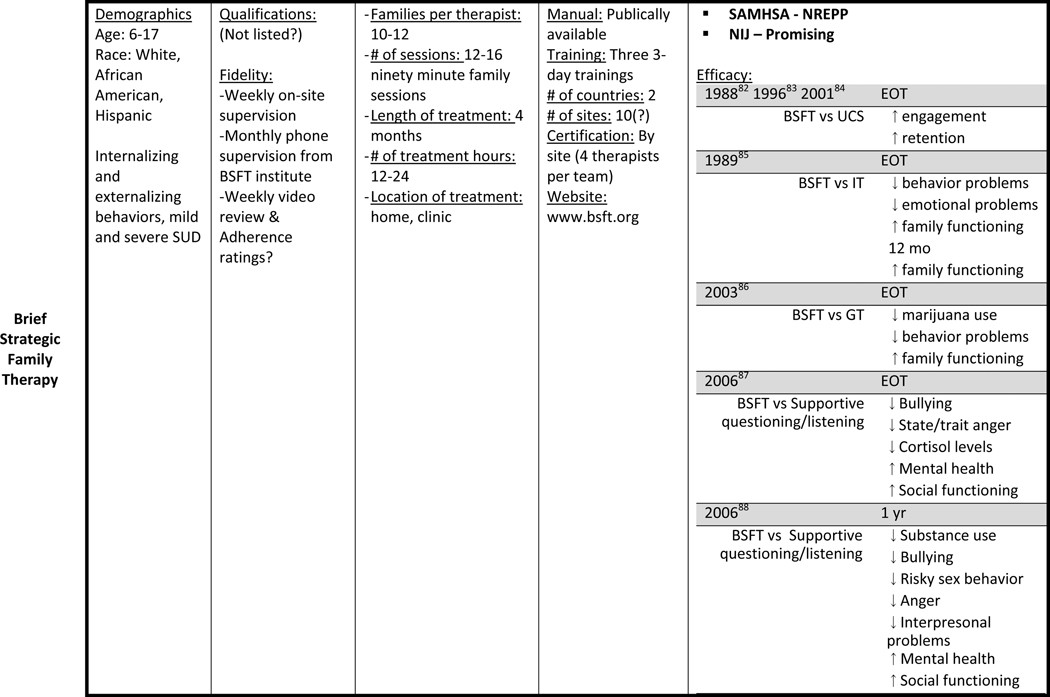

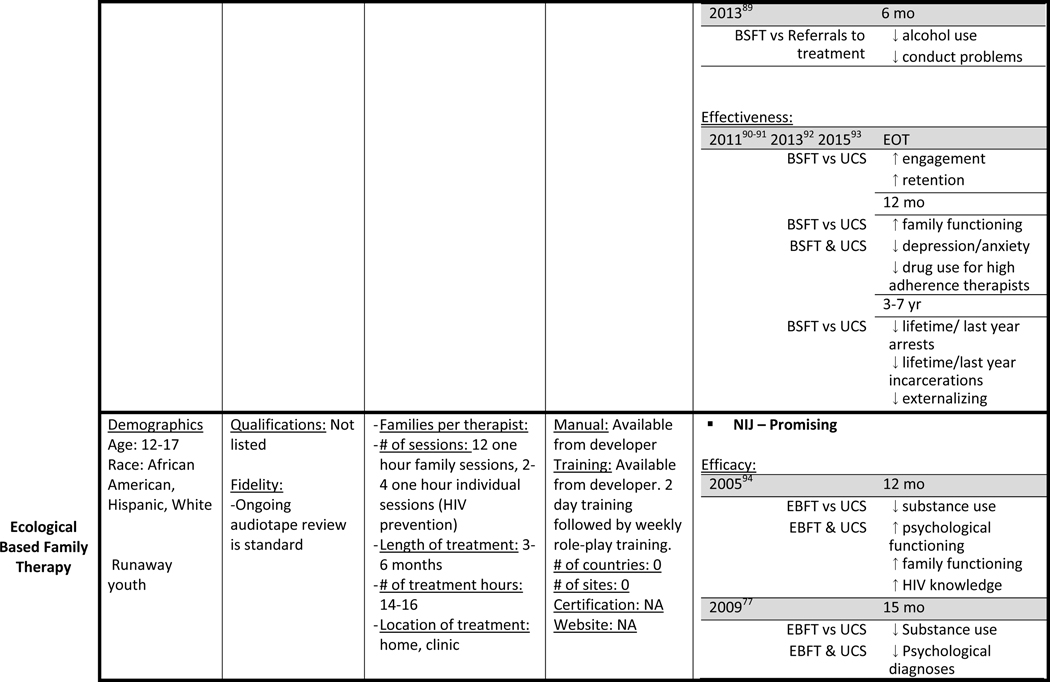

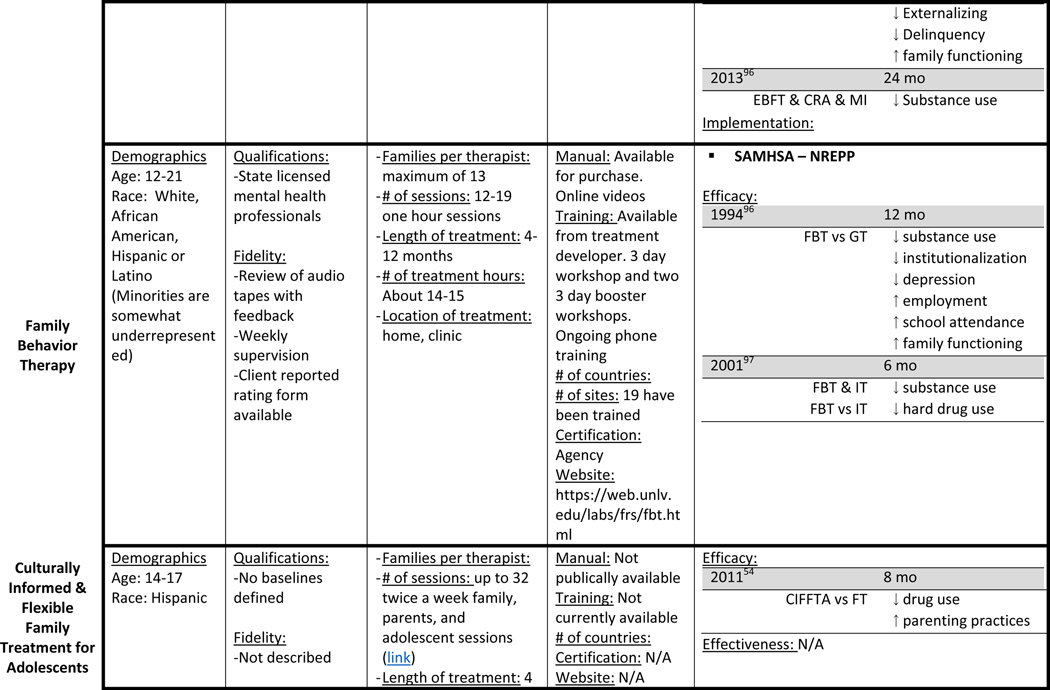

Table 1 presents information on the various family-based treatments for adolescent substance use. It includes information on the populations treated, the location of the service, therapist qualifications, treatment parameters, and the stage of research. Our goal is that this summary together with the narrative of each mode described above will inform the reader in the selection of an appropriate treatment for adolescent substance users.

Table 1:

Treatment Characteristics – Target population, Treatment parameters, Dissemination and Research Evidence

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

|

Abbreviations:7C = The Seven Challenges; BSFT = Brief Strategic Family Therapy; CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CIFFTA = Culturally Informed Flexible Family Treatment for Adolescents; CRA = Community Reinforcement Approach; CT = Combined treatment (FFT and CWD); CWD = Coping With Depression; EBFT = Ecologically Based Family Therapy; EOT = End of Treatment; FBT = Family Behavior Therapy; FFT = Functional Family Therapy; FT = Family Therapy; GT = Group Therapy; IT = Individual Therapy; MET = Motivational Enhancement Therapy; MDFT = Multidimensional Family Therapy; MI = Motivational Interviewing; MST = Multisystemic Therapy; NTC = No Treatment Control; SOFT = Strengths Oriented Family Therapy; UCS = Usual Community Services

Conclusion

The increasing evidence for the impact of family interventions above that of individual and group intervention adds to prior evidence on the importance of family protective and risk factors to support the importance of the family in adolescent development and drug use. Several ecological family based treatments have been evaluated for efficacy, effectiveness and are now widely implemented in the US and abroad. Fidelity to these manualized interventions are key for sustained outcomes. Some new models are accruing evidence for specific populations and are on their way for testing their effectiveness in community settings. Continued research into the implementation and dissemination as well as formal cost benefit analyses are needed to further document FBT’s effectiveness.

Key Points:

Family is a central system in adolescent’s development

Ecological Family based treatments have been proven the most effective of approaches for adolescent SUD

Several family based treatments have been widely studied and have robust evidence of efficacy, effectiveness and are being implemented in community settings, others are promising and at earlier stages of testing

[Box – MST]

MST is founded on 9 core treatment principles which are:

Finding the fit – Proper assessment allows the therapist to understand how the adolescent’s drug use “fits” within the context of multiple systems.

Focusing on positives and strengths – The positive attributes and strengths of the family, community and the adolescent are leveraged to bring about change.

Increasing responsibility – Therapy should be directed toward helping individuals engage in responsible behavior such as attending school, stopping drug use, and increasing caregivers’ patience.

Present focused, action oriented, and well-defined – Therapy emphasizes taking action to solve specific problems that are occurring now rather than past problems.

Targeting sequences – Interventions are targeted at changing multiple interactions that are working together to support problematic drug use.

Developmentally appropriate – Interventions are formulated to match the developmental stage of the adolescent.

Continuous effort – Interventions are meant to be applied throughout the week, requiring effort from various family members.

Evaluation and accountability – The efficacy of therapy is assessed according to various indicators of progress across the adolescent’s life (i.e. report cards, drug screens, parent reports)

Generalization – Although targeting specific problems, interventions should empower caregivers to handle other problems in other domains.

[Box - FFT guiding principles for bringing about change] (Sexton & Alexander, 2004)

Principle 1: Understanding clients

-

-

This principle includes understanding the broader community and cultural contexts within which the client and family are situated. It emphasizes the importance of identifying and working with clients’ strengths as well as their risk factors.

Principle 2: Understanding client problems systemically

-

-

Presenting problems are understood as relational problems - they are the result of problematic patterns of relating within families. They are seen as functional in that they are engaged in for obtaining outcomes within an already problematic system.

Principle 3: Understanding therapy and the role of the therapist as fundamentally a relational process.

-

-

The relational engagement between therapist and family is viewed as cooperation between experts. By respecting the families, identifying meaningful change for them, and adjusting therapy to match each unique situation, therapists can guide families through the phases of treatment.

[Box – MDFT Assumptions Underlying Treatment] (Liddle, 2010, p. 417–418 (Weisz/Kazdin))

Adolescent drug abuse is a multidimensional phenomenon – it is based on an ecological and developmental perspective that takes into account various social contexts.

Family functioning is instrumental in creating new, developmentally adaptive lifestyle alternatives for adolescents.

Problem situations provide information and opportunity – these are often the target of interventions.

Change is multifaceted, multideterminded, and stage oriented – although complex, the coordination of treatment across systems and domains in a sequential way.

Motivation is malleable but it is not assumed – clients are not always going to be motivated to engage in treatment and increasing motivation is central to MDFT

Multiple therapeutic alliances are required and they create a foundation for change – relationships with each family member and others are important.

Individualized interventions foster developmental competencies – treatment must fit the family’s historical and cultural contexts to be successful.

Treatment occurs in stages; continuity is stressed – as treatment proceeds, finding the continuity in themes across the stages is important for change to occur.

Therapist responsibility is emphasized – therapists are responsible for many aspects of MDFT treatment and must adjust their approach relevant to feedback.

Therapist attitude is fundamental to success – they are optimistic and realistic in advocating for adolescent and parent improvement.

[Box – BSFT Foundational Concepts] (Szapocznik et al., 2003)

-

-

Systems – A social system assumes that a group of people, in BSFT’s case the family, is better understood as a whole organism rather than as individual independent actors. Every action that one member of the system undertakes can be understood as affecting the whole system, thus positive changes in the adolescent or the parent may bring changes to the whole family.

-

-

Structure –Patterns of social interaction are habitual and repetitive interactions that can be understood as structure. As family members interact with each other, structure, sometimes maladaptive, can be formed that promote adolescents to behave poorly.

-

-

Strategy - The strategic aspects of treatment refer to the practical (including whatever interventions that will help bring about change), problem-focused (limiting the scope of treatment to interactions related to the presenting problem) and planned (based on the therapist’s assessment of problematic interactions) nature of BSFT treatment.

-

-

Content versus process – More important than what is said in BSFT therapy, the quality of the listening, sharing, and interacting between the family members helps the therapist diagnose and work on problematic repetitive patterns.

-

-

Context – Relying on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) theory, BSFT assumes that individuals are affected by the various social contexts within which they exist. The family is the most important of these contexts, but peers, neighborhoods, wider culture, and counseling can also be understood as contributing contexts to adolescent development and behavior.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Author Jose Szapocznik is the developer of the BSFT model and has copyrighted the intervention. He is also the director for the BSFT training institute. Authors Horigian and Anderson have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal Study of Co-occurring Psychiatric Disorders and Substance Use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Swift W, Moore E, Patton GC. Outcomes of occasional cannabis use in adolescence: 10-year follow-up study in Victoria, Australia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(4):290–295. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult Consequences of Late Adolescent Alcohol Consumption: A Systematic Review of Cohort Studies. PLoS Med 2011;8(2):e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge Drinking and Associated Health Risk Behaviors Among High School Students. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. The Influence of Substance Use on Adolescent Brain Development. Clin EEG Neurosci 2009;40(1):31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe CL. Multidimensional family therapy: addressing co-occurring substance abuse and other problems among adolescents with comprehensive family-based treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):563–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen-Smit E, Verdurmen JEE, Engels RCME. The Effectiveness of Family Interventions in Preventing Adolescent Illicit Drug Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2015;18(3):218–239. doi: 10.1007/s10567-015-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogue A, Henderson CE, Ozechowski TJ, Robbins MS. Evidence Base on Outpatient Behavioral Treatments for Adolescent Substance Use: Updates and Recommendations 2007–2013. Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2014;43(5):695–720. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.915550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belendiuk KA, Riggs P. Treatment of Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. Curr Treat Options Psych 2014;1(2):175–188. doi: 10.1007/s40501-014-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat 2013;44(2):145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabria B, Shakeshaft AP, Havard A. A systematic and methodological review of interventions for young people experiencing alcohol-related harm. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1406–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macgowan MJ, Engle B. Evidence for Optimism: Behavior Therapies and Motivational Interviewing in Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):527–545. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldron HB, Turner CW. Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Adolescent Substance Abuse. Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2008;37(1):238–261. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker SJ, Curry JF. Outpatient interventions for adolescent substance abuse: A quality of evidence review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76(4):531–543. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin SA, Christian S, Berkeljon A, Shadish WR. The Effects of Family Therapies for Adolescent Delinquency and Substance Abuse: A Meta-analysis. J Marital Fam Ther 2012;38(1):281–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szapocznik J, Douglas J. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR, eds. Drug Abuse: Origins & Interventions. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1999:331–366. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing Substance Abuse in Hispanic Immigrant Adolescents: An Ecodevelopmental, Parent-Centered Approach. Hisp J Behav Sci 2003;25(4):469–500. doi: 10.1177/0739986303259355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnette ML, Oshri A, Lax R, Richards D, Ragbeer SN. Pathways from harsh parenting to adolescent antisocial behavior: A multidomain test of gender moderation. Dev Psychopathol 2012;24(Special Issue 03):857–870. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skeer M, McCormick MC, Normand S-LT, Buka SL, Gilman SE. A prospective study of familial conflict, psychological stress, and the development of substance use disorders in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104(1–2):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshri A, Rogosch FA, Burnette ML, Cicchetti D. Developmental pathways to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: Child maltreatment, emerging personality, and internalizing versus externalizing psychopathology. Psychol Addict Behav 2011;25(4):634–644. doi: 10.1037/a0023151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Dodge KA. Child, Parent, and Peer Predictors of Early-Onset Substance Use: A Multisite Longitudinal Study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2002;30(3):199–216. doi: 10.1023/A:1015183927979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, Feighner JA. Patterns of Alcohol and Drug Use in Adolescents Can Be Predicted by Parental Substance Use Disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Kim HK, Yoerger K. Growth in alcohol use in at-risk adolescent boys: Two-part random effects prediction models. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;105(1–2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soloski KL, Kale Monk J, Durtschi JA. Trajectories of Early Binge Drinking: A Function of Family Cohesion and Peer Use. J Marital Fam Ther January 2015:n/a - n/a. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson CE, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Hawes SW, Liddle HA. Parenting Practices as Mediators of Treatment Effects in an Early-Intervention Trial of Multidimensional Family Therapy. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(4):220–226. doi: 10.1080/00952990903005890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of Parental Monitoring and Peer Deviance on Substance Use and Delinquency. J. Marriage Fam 2006;68(4):1084–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00315.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montgomery C, Fisk JE, Craig L. The effects of perceived parenting style on the propensity for illicit drug use: the importance of parental warmth and control. Drug Alcohol Rev 2008;27(6):640–649. doi: 10.1080/09595230802392790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caughlin JP, Malis RS. Demand/Withdraw Communication between Parents and Adolescents: Connections with Self-Esteem and Substance Use. J Soc Pers Relat 2004;21(1):125–148. doi: 10.1177/0265407504039843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beyers JM, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: the United States and Australia. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KCA. Substance Use Among Early Adolescent Girls: Risk and Protective Factors. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(2):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bukstein OG. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Substance Use Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(6):609–621. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000159135.33706.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic Therapy for Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic Treatment of Substance-Abusing and -Dependent Delinquents: Outcomes, Treatment Fidelity, and Transportability. Ment Health Serv Res 1999;1(3):171–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zajac K, Randall J, Swenson CC. Multisystemic Therapy for Externalizing Youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2015;24(3):601–616. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sexton TL, Alexander JF. Functional Family Therapy Clinical Training Manual Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liddle HA, Rodriguez RA, Dakof GA, Kanzki E, Marvel FA Multidimensional family therapy: a science-based treatment for adolescent drug abuse In: Lebow J, editor. Handbook of Clinical Family Therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2005, p. 128–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liddle HA. Multidimensional Family Therapy Treatment (MDFT) for the Adolescent Cannabis users; Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) manual series. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. Vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liddle HA. Treating adolescent substance abuse using multidimensional family therapy In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, eds. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents (2nd Ed.). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2010:416–432. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowe C, Rigter H, Henderson C, et al. Implementation fidelity of Multidimensional Family Therapy in an international trial. J Subst Abuse Treat 2013;44(4):391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szapocznik J; Hervis O; Schwartz S NIH Publication 03–4751 Bethesda, Md: NationalInstitute on Drug Abuse; 2003. Brief Strategic Family Therapy for Adolescent Drug Abuse [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horigian VE, Szapocznik J. Brief strategic family therapy: Thirty-five years of interplay among theory, research, and practice in adolescent behavior problems In: Handbook of Adolescent Drug Use Prevention: Research, Intervention Strategies, and Practice. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2015:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, et al. Brief strategic family therapy versus treatment as usual: Results of a multisite randomized trial for substance using adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79(6):713–727. doi: 10.1037/a0025477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM. Breakthroughs in family therapy with drug-abusing problem youth. New York: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, Puccinelli MJ, Henderson C, Szapocznik J. Therapist Adherence in Brief Strategic Family Therapy for Adolescent Drug Abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0022146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horigian VE, Feaster DJ, Robbins MS, et al. A cross-sectional assessment of the long term effects of brief strategic family therapy for adolescent substance use. Am J Addict 2015;24(7):637–645. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azrin NH, Donohue B, Teichner GA, Crum T, Howell J, DeCato LA. A Controlled Evaluation and Description of Individual-Cognitive Problem Solving and Family-Behavior Therapies in Dually-Diagnosed Conduct-Disordered and Substance-Dependent Youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2001;11(1):1–43. doi: 10.1300/J029v11n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azrin NH, McMahon PT, Donohue B, et al. Behavior therapy for drug abuse: A controlled treatment outcome study. Behav Res Ther 1994;32(8):857–866. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90166-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donohue B, Azrin N, Allen DN, et al. Family Behavior Therapy for Substance Abuse and Other Associated Problems A Review of Its Intervention Components and Applicability. Behav Modif 2009;33(5):495–519. doi: 10.1177/0145445509340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santisteban DA, Mena MP. Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents: A Tailored and Integrative Treatment for Hispanic Youth. Fam Process. 2009;48(2):253–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santisteban DA, Mena MP, McCabe BE. Preliminary Results for an Adaptive Family Treatment for Drug Abuse in Hispanic Youth. J Fam Psychol 2011;25(4):610–614. doi: 10.1037/a0024016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith DC, Hall JA. Strengths-oriented family therapy for adolescents with substance abuse problems. Soc Work. 2008;53(2):185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall JA, Smith DC, & Williams JK. Strengths-oriented family therapy (SOFT): A manual guided treatment for substance-involved teens and their families In: Lecroy CW (Ed.) Handbook of Evidence-Based Treatment Manuals for Children and Adolescents, New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2008:491–545 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith DC, Hall JA, Williams JK, An H, Gotman N. Comparative Efficacy of Family and Group Treatment for Adolescent Substance Abuse. Am J Addict 2006;15:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown TL, Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Multisystemic Treatment of Substance Abusing and Dependent Juvenile Delinquents: Effects on School Attendance at Posttreatment and 6-Month Follow-Up. Children’s Services. 1999;2(2):81–93. doi: 10.1207/s15326918cs0202_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(7):868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henggeler SW, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Randall J, Shapiro SB, Chapman JE. Juvenile drug court: Enhancing outcomes by integrating evidence-based treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74(1):42–54. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rowland M, Chapman JE, Henggeler SW. Sibling Outcomes from a Randomized Trial of Evidence-Based Treatments with Substance Abusing Juvenile Offenders. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2008;17(3):11–26. doi: 10.1080/15470650802071622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Stouwe T, Asscher JJ, Stams GJJM, Deković M, van der Laan PH. The effectiveness of Multisystemic Therapy (MST): a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014;34(6):468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Parker K, Diamond GS, Barrett K, Tejeda M. Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(4):651–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Treating adolescent drug abuse: a randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;27(3):197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Ungaro RA, Henderson CE. Early intervention for adolescent substance abuse: pretreatment to posttreatment outcomes of a randomized clinical trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and peer group treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2004;36(1):49–63. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10399723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Multidimensional family therapy for young adolescent substance abuse: twelve-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009;77(1):12–25. doi: 10.1037/a0014160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hendriks V, van der Schee E, Blanken P. Treatment of adolescents with a cannabis use disorder: main findings of a randomized controlled trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in The Netherlands. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;119(1–2):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rigter H, Henderson CE, Pelc I, et al. Multidimensional family therapy lowers the rate of cannabis dependence in adolescents: a randomised controlled trial in Western European outpatient settings. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;130(1–3):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schaub MP, Henderson CE, Pelc I, et al. Multidimensional family therapy decreases the rate of externalising behavioural disorder symptoms in cannabis abusing adolescents: outcomes of the INCANT trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Rowe CL, et al. A randomized clinical trial of family therapy in juvenile drug court. J Fam Psychol 2015;29(2):232–241. doi: 10.1037/fam0000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parsons B, Alexander J. Short-term family intervention: A therapy outcome study. J Consult Clin Psychol [serial online]. October 1973;41(2):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alexander J, Parsons B. Short-term behavioral intervention with delinquent families: Impact on Fam Process and recidivism. J Abnorm Psychol June 1973;81(3):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klein N, Alexander J, Parsons B. Impact of family systems intervention on recidivism and sibling delinquency: A model of primary prevention and program evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol June 1977;45(3):469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.1. Friedman AS: Family therapy vs. parent groups: Effects on adolescent drug abusers. Am J Fam Ther 1989, 17:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, Turner CW, Peterson TR. Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 4- and 7-month assessments. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69(5):802–813. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.5.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL: Comparison of Family Therapy Outcome With Alcohol-Abusing, Runaway Adolescents. J Marital Fam Ther 2009, 35:255–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hops H, Ozechowski TJ, Waldron HB, Davis B, Turner CW, Brody JL, Barrera M: Adolescent Health-Risk Sexual Behaviors: Effects of a Drug Abuse Intervention. AIDS Behav 2011, 15:1664–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rohde P, Waldron HB, Turner CW, Brody J, Jorgensen J. Sequenced Versus Coordinated Treatment for Adolescents with Comorbid Depressive and Substance Use Disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82(2):342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0035808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sexton T, Turner CW. The Effectiveness of Functional Family Therapy for Youth with Behavioral Problems in a Community Practice Setting. J Fam Psychol 2010;24(3):339–348. doi: 10.1037/a0019406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hartnett D, Carr A, Sexton T. The Effectiveness of Functional Family Therapy in Reducing Adolescent Mental Health Risk and Family Adjustment Difficulties in an Irish Context. Fam Proc November 2015:n/a - n/a doi: 10.1111/famp.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Brickman AL, et al. Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families in treatment: A strategic structural systems approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56(4):552–557. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Santisteban DA, Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Murray EJ, LaPerriere A. Efficacy of intervention for engaging youth and families into treatment and some variables that may contribute to differential effectiveness. J Fam Psychol 1996;10(1):35–44. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.1.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coatsworth JD, Santisteban DA, McBride CK, Szapocznik J. Brief Strategic Family Therapy versus Community Control: Engagement, Retention, and an Exploration of the Moderating Role of Adolescent Symptom Severity*. Fam Process. 2001;40(3):313–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4030100313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Szapocznik J, Rio A, Murray E, et al. Structural family versus psychodynamic child therapy for problematic Hispanic boys. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989;57(5):571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Santisteban DA, Perez-Vidal A, Coatsworth JD, et al. Efficacy of Brief Strategic Family Therapy in Modifying Hispanic Adolescent Behavior Problems and Substance Use. J Fam Psychol 2003;17(1):121–133. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Kaplan P, et al. Influence of family therapy on bullying behaviour, cortisol secretion, anger, and quality of life in bullying male adolescents: A randomized, prospective, controlled study. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(6):355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nickel M, Luley J, Krawczyk J, et al. Bullying girls - changes after brief strategic family therapy: a randomized, prospective, controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75(1):47–55. doi: 10.1159/000089226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Valdez A, Cepeda A, Parrish D, Horowitz R, Kaplan C. An Adapted Brief Strategic Family Therapy for Gang-Affiliated Mexican American Adolescents. Res Soc Work Pract 2013;23(4):383–396. doi: 10.1177/1049731513481389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, et al. Brief strategic family therapy versus treatment as usual: Results of a multisite randomized trial for substance using adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79(6):713–727. doi: 10.1037/a0025477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, Puccinelli MJ, Henderson C, Szapocznik J. Therapist Adherence in Brief Strategic Family Therapy for Adolescent Drug Abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0022146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Horigian VE, Weems CF, Robbins MS, et al. Reductions in Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Youth Receiving Substance Use Treatment. Am J Addict 2013;22(4):329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Horigian VE, Feaster DJ, Robbins MS, et al. A cross-sectional assessment of the long term effects of brief strategic family therapy for adolescent substance use. Am J Addict 2015;24(7):637–645. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL. Ecologically-Based Family Therapy Outcome with Substance Abusing Runaway Adolescents. J Adolesc 2005;28(2):277–298. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Slesnick N, Erdem G, Bartle-Haring S, Brigham GS. Intervention with substance-abusing runaway adolescents and their families: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81(4):600–614. doi: 10.1037/a0033463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Azrin NH, McMahon PT, Donohue B, et al. Behavior therapy for drug abuse: A controlled treatment outcome study. Behav Res Ther 1994;32(8):857–866. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90166-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Azrin NH, Donohue B, Teichner GA, Crum T, Howell J, DeCato LA. A Controlled Evaluation and Description of Individual-Cognitive Problem Solving and Family-Behavior Therapies in Dually-Diagnosed Conduct-Disordered and Substance-Dependent Youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2001;11(1):1–43. doi: 10.1300/J029v11n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Azrin NH, Donohue B, Teichner GA, Crum T, Howell J, DeCato LA. A Controlled Evaluation and Description of Individual-Cognitive Problem Solving and Family-Behavior Therapies in Dually-Diagnosed Conduct-Disordered and Substance-Dependent Youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2001;11(1):1–43. doi: 10.1300/J029v11n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]