Abstract

Introduction:

Although opioid prescribing has decreased since 2010, overdose deaths involving illicit opioids have continued to rise. This study explores prescribing patterns prior to fatal overdose of decedents who died of prescription and illicit opioid overdoses.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in 2019 and included all 1,893 Illinois residents who died of an opioid-related overdose in 2016. Each decedent was linked to any existing Prescription Monitoring Program records, calculating weekly morphine milligram equivalents for 52 weeks prior to overdose.

Results:

Among the 1,893 fatal opioid overdoses, 309 involved any prescription opioid and 1,461 involved illicit opioids without the involvement of prescription opioids. The death rate due to illicit opioids was 23/100,000 among black residents versus 10.5/100,000 among whites. During the last year of life, 76% of prescription opioid decedents filled any opioid prescription totaling 10.7 prescriptions per decedent, compared with 36% of illicit opioid decedents totaling 2.6 prescriptions per decedent. During the last week of life, 33% of prescription opioid decedents filled an opioid prescription totaling 0.42 prescriptions per decedent, compared with 4% of illicit opioid decedents totaling 0.05 prescriptions per decedent.

Conclusions:

Prescribing patterns alone may not be sufficient to identify patients who are at high risk for opioid overdose, especially for those using illicit opioids. Interventions aimed at reducing opioid overdoses should take into account different patterns of opioid prescribing associated with illicit and prescription opioid overdose deaths and be designed around the local characteristics of the opioid overdose epidemic.

INTRODUCTION

Opioids were involved in 47,600 fatal overdoses in the U.S. in 2017, including 17,029 deaths involving prescription opioids.1 Access to prescription opioids is thought to be a significant risk factor for subsequent overdose involving both prescription opioids and illicit opioids like heroin and fentanyl.2 However, although opioid prescribing has decreased significantly since 2010,3 the number of deaths involving prescription opioids has remained constant, and deaths involving illicit opioids have continued to rise.4 This may be related to the fact that reducing access to prescription opioids is associated with transition to heroin use,5,6 although it is not known whether decreasing access to prescription opioids among patients actively prescribed opioids immediately increase the risk of subsequent fatal overdose involving illicit opioids. This study explores the relationships between receipt of an opioid prescription and fatal opioid overdose by examining opioid prescribing levels for 1 year prior to fatal overdose by decedents whose overdose involved prescription and illicit opioids.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of all Illinois residents who died of an opioid overdose in 2016. Death records of Illinois residents who died of an overdose in 2016 were extracted from the Illinois Vital Records using ICD-10 codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14. Review of death certificate text using a custom algorithm with manual review revealed 1,893 deaths involving opioids.7 Overdoses were stratified as prescription opioid–involved if they involved hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, tramadol, or buprenorphine. Overdoses that did not involve any of these opioids, but involved heroin, fentanyl, or fentanyl analogues were classified as illicit opioid overdoses. Overdoses that included both prescription and illicit opioids were categorized as prescription opioid–involved overdoses (n=77). Overdoses involving non-specified opioids or opioids not mentioned above were excluded (n=123). Death records were linked to any existing Illinois Prescription Monitoring Program records from the year before fatal overdose using a fuzzy match on first name, last name, date of birth. The Illinois Prescription Monitoring Program records all schedule II–V drugs dispensed from retail pharmacies. Total morphine milligram equivalent (MME) doses per day (Figure 1) was calculated using the date each prescription was filled, days’ supply, and dose converted to MME using conversion factors compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.8 Decedents’ counties were classified as rural or urban based on definitions from the U.S. Health Research and Services Administration.9 Estimates of the resident population were obtained from the American community survey.10 Statistical testing was performed using chi-square tests for binary variables, t-tests for age of decedents, and Wilcoxon rank sums tests for all other continuous variables due to non-normal distribution. Data analysis was performed in R, version 3.4 in 2019. This study was granted an exemption from review by the Illinois Department of Public Health IRB because it was performed as public health surveillance aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality related to opioid overdoses.

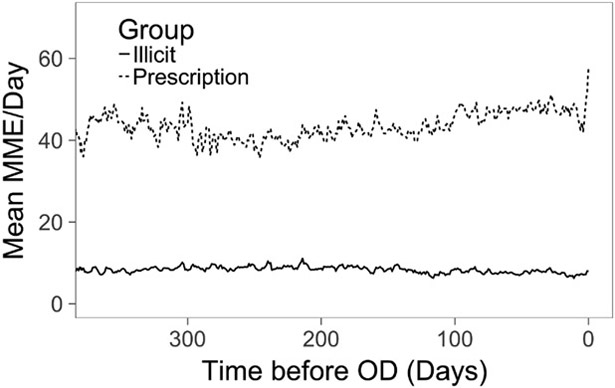

Figure 1.

Daily morphine milligram equivalent (MME) of decedents stratified by whether overdose involved prescription opioids for one year prior to fatal overdose.

Notes: Daily MME is the sum of all active prescriptions based on the start date, days’ supply, and MME. Decedents in prescription group died of overdoses involving any prescription opioids with or without the additional involvement of illicit opioids. Decedents in illicit group died of overdose involving heroin, fentanyl, or fentanyl analogues without the involvement of prescription opioids.

OD, overdose.

RESULTS

There were 1,893 deaths involving opioids, corresponding to a death rate of 14.8/100,000. Of these deaths, 309 involved prescription opioids (2.4/100,000) and 1,461 involved illicit opioids without any prescription opioids (11.4/100,000). Non-Hispanic whites comprised 82.6% of prescription opioid decedents and 58.2% of illicit opioid decedents. The illicit opioid death rate was higher among black residents than non-Hispanic whites (23 vs 10.6/100,000 p<0.001), whereas the reverse was true for the prescription opioid death rate (1.4 vs 3.2/100,000 p<0.001). Compared with overdoses involving prescription opioids, illicit opioid overdoses were more likely to also involve cocaine (24.6% vs 10.7% p<0.001) and alcohol (20.6% vs 11.3% p<0.001). During the last year of life, 76% of prescription opioid decedents filled any opioid prescription, compared with 36% of illicit opioid decedents. Total prescription volume was 10.7 prescriptions per decedent among prescription opioid decedents and 2.6 among illicit opioid decedents. In the last week of life, 33.0% of prescription opioid decedents filled an opioid prescription, compared with 4.6% of illicit opioid decedents. Figure 1 shows that mean daily MME of active prescriptions was constant among illicit opioid decedents whereas there was an increase in MME among prescription opioid decedents immediately before overdose. This increase was driven by an increase in the number of prescriptions filled, from 0.2 prescriptions per week during the last year of life to 0.42 during the last week of life. High-risk prescribing patterns were more common among prescription opioid decedents, as 54.3% met at least one risk factor (four or more pharmacies, four or more prescribers, ≥100 MME/day), compared with 30.5% of illicit opioid decedents (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with national trends, the majority of opioid overdoses involved illicit opioids without the involvement of prescription opioids. Although recent studies have suggested that decreasing access to prescription opioids may result in increased deaths involving illicit opioids,6 there was no decrease in opioid prescribing during the last year, or the last week of life among decedents who died of illicit opioid overdose. Total utilization of prescribed opioids among illicit opioid decedents was relatively low throughout the last year of life, with 2.6 prescriptions per decedent, compared with 10.7 among prescription opioid decedents. A possible explanation for this result may be that a substantial amount of time elapses between transitioning from prescription to illicit opioids and eventual overdose. This implies that patients who are at high risk for illicit opioid overdose may be difficult to identify from prescription patterns alone.

Though prescription opioids are commonly obtained through non-legal means,11 this study suggests that legally prescribed opioids were involved in a subset of fatal overdoses. Among prescription opioid decedents, weekly prescription volume doubled during the last week of life compared with the average volume during the last year of life, and almost one third filled a prescription for an opioid involved in the fatal overdose during the last week of life. However, prescribing patterns alone cannot be used to identify which decedents may be at risk for fatal overdose as only about half of prescription opioid decedents met any of the established risk factors for opioid overdose including prescriptions ≥100MME/day, utilizing four or more prescribers, and four or more pharmacies.12,13

The demographics of decedents in this study reveal several patterns that highlight the localized nature of the opioid epidemic. In Illinois, prescription opioid decedents were almost evenly split between male and female decedents, whereas the national rate of overdoses involving prescription opioids in the same year was 44% higher among male decedents.1 Whereas nationally illicit opioid death rates are higher among whites,14 the reverse was true in Illinois. These illicit opioid decedents are more likely than prescription opioid decedents to be urban and to co-ingest alcohol or cocaine at the time of overdose. Studies indicate that utilization of opioid use disorder treatment is lower among urban populations, blacks, and those with comorbid alcohol use disorder, suggesting that new approaches may be needed to ensure disadvantaged communities are able to access evidence based treatments for substance use disorder.15,16

Limitations

Limitations of this study include analysis of data from a single state and year. By focusing on decedents, data were excluded on non-fatal overdoses and the prevalence of illicit and prescription opioid use in the state. The study relied on death certificates, which are completed by local medical examiners and coroners who may have inconsistent practices, and the authors did not review the unique circumstances surrounding each death. Finally, Prescription Monitoring Program records do not record whether patients are taking medications as prescribed or are receiving diverted opioids.

CONCLUSIONS

Decedents who die of prescription opioid overdoses experience an increase in prescribing immediately before overdose, whereas decedents who die of illicit opioids have lower and constant levels of prescribing during the last year of life. Prescribing patterns alone may not be sufficient to identify patients who are at high risk for opioid overdose, especially for those using illicit opioids. A multifaceted response to the opioid epidemic should be informed by an understanding of pathways leading to opioid overdose and include the delivery of evidence-based services that are tailored to the local characteristics of opioid overdose decedents.17

Table 1.

Characteristics of Opioid Overdose Decedents Stratified by Whether Overdose Involved Prescription or Illicit Opioids

| Variable | Illicit (N=1,461) | Prescription (N=309) |

|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 1,123 (76.9) | 165 (53.4) *** |

| Race and ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| Black | 422 (29.2) | 26 (8.5) *** |

| Hispanic | 162 (11.2) | 24 (7.9) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 841 (58.2) | 252 (82.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.7 (12.3) | 46.6 (13.7) *** |

| Rural, N (%) | 100 (6.8) | 58 (18.8) *** |

| OD involved, N (%) | ||

| Cocaine | 360 (24.6) | 33 (10.7)*** |

| Alcohol | 301 (20.6) | 35 (11.3)*** |

| An opioid for which prescription was filled ≤7 days before OD | 12 (0.8) | 96 (31.1)*** |

| Opioid prescribing | ||

| Time between last prescription filled and fatal OD in days, median (IQR) | 66 (18–189) | 10 (3–29)*** |

| ≥4 pharmacies during last year before OD, N, (%) | 83 (15.6) | 59 (25.2)** |

| ≥4 prescribers during last year before OD, N, (%) | 130 (24.4) | 96 (41.0)*** |

| Prescriptions averaging ≥100 MME/day during last year before OD, N (%) | 25 (4.7) | 41 (17.5)*** |

| Any risk factor (≥4 pharmacies, ≥4 prescribers, ≥100 MME/day) during last year before OD, N (%) |

162 (30.5) | 127 (54.3)*** |

| Number of decedents who filled at least one opioid prescription, N (%) | ||

| Last year before OD | 531 (36.3) | 234 (75.7)*** |

| Last week before OD | 60 (4.1) | 102 (33.0)*** |

| Total number of prescriptions filled per decedent | ||

| Last year before OD, total for year (mean per week) | 2.6 (0.05) | 10.7 (0.21)*** |

| Last week before OD, total for year | 0.05 | 0.42*** |

| Supply per prescription in days, median (IQR) | ||

| Last year before OD | 15 (5–30) | 30 (10–30)*** |

| Last week before OD | 10 (3–30) | 30 (15–30)*** |

| Dose per prescription in MME/day, median (IQR) | ||

| Last year before OD | 30 (20–60) | 43 (30–80)*** |

| Last week before OD | 34 (20–60) | 48 (30–90)* |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

OD, overdose; MME, morphine milligram equivalent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors were funded by the University of Chicago Institute of Politics (ABA), National Institute on Drug Abuse UG3DA044829 (MTP), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R00HS022433 (MTP). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

ABA receives consulting fees from AMW LLc for performing clinical research related to spinal surgery.

No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–1427. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6751521e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36(1):559–574. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697–704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(329). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329_tables-508.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. 2016;374(2):154–163. 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the U.S. opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394–1400. 10.2105/ajph.2018.304590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbasi A, Clark H, Adbodo N, Layden J, Pho M. Learning algorithm to identify drugs involved in drug overdose deaths from literal text on death certificates. Paper presented at: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists Annual Conference; June 10–14, 2019; Palm Beach, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Data resources: analyzing prescription data and morphine milligram equivalents (MME). www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html. Updated July 16, 2019 Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 9.U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Defining rural population. www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html Published 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population. Washington, DC; 2016. https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/PEP/2016/PEPANNRES. Accessed March 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–248. 10.1056/nejmsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):64–70. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumblatt JAG, Wiedeman C, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, Paulozzi LJ, Jones TF. High-risk use by patients prescribed opioids for pain and its role in overdose deaths. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):796–801. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander MJ, Kiang MV, Barbieri M. Trends in black and white opioid mortality in the United States, 1979–2015. Epidemiology. 2018;29(5):707–715. 10.1097/ede.0000000000000858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasi AB, Salisbury-Afshar E, Jovanov D, et al. Health care utilization of opioid overdose decedents with no opioid analgesic prescription history. J Urban Heal. 2019;96(1):38–48. 10.1007/s11524-018-00329-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L-T, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:117–127. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):182–186. 10.2105/ajph.2017.304187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]