Abstract

The recognition that the successful clinical use of MMP inhibitors will require quantitative correlation of MMP activity with disease type, and to disease progression, has stimulated intensive effort toward the development of sensitive assay methods, improved analytical methods for the determination of the structural profile for MMP-sub-type inhibition, and the development of new methods for the determination – in both quantitative and qualitative terms – of MMP activity. This chapter reviews recent progress toward these objectives, with particular emphasis on the quantitative and qualitative profiling of MMP activity in cells and tissues. Quantitative determination of MMP activity is made from the concentration of the MMP from the tissue, using immobilization of a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor on a chromatography resin. Active MMP, to the exclusion of MMP zymogens and endogenous TIMP-inhibited MMPs, is retained on the column. Characterization of the MMP sub-type(s) follows from appropriate analysis of the active MMP eluted from the resin. Qualitative determination of MMP involvement in disease can be made using an MMP sub-type-selective inhibitor. The proof of principle, with respect to this qualitative determination of the disease involvement of the gelatinase MMP-2 and MMP-9 sub-types, is provided by the class of thiirane-based MMP mechanism-based inhibitors (SB-3CT as the prototype). Positive outcomes in animal models of disease having MMP-2 and/or -9 dependency follow administration of this MMP inhibitor, whereas this inhibitor is inactive in disease models where other MMPs (such as MMP-14) are involved.

Keywords: Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP), hydroxamate small molecule microarrays, affinity chromatography resin

1. Overview

The optimism that non-selective inhibitors of the MMP family would possess clinical antitumor and antimetastatic activity (1–9) has given way to the sober realization that the relationships among the expression of MMP sub-type, the different roles of the extracellular matrix as an MMP substrate, the inhibitor structure, and the temporal and spatial evolution of the cancer are extraordinarily complex (10–20). As this realization has developed over the past decade, experimental enquiry concerning the MMP family has increasingly addressed the selectivity and specificity aspects of this complexity: Which MMP sub-types are culpable, and can this information be used for diagnosis? What sub-type selectivity should an MMP inhibitor possess? For which cancers, and at what times during the clinical progression of these cancers, is intervention with an MMP inhibitor therapeutically useful? In no circumstance are the answers yet complete. In many circumstances, however, the inchoate answers affirm the opinion that the MMPs remain valid therapeutic targets for the amelioration of disease (not just cancer, but also including inflammation, atherosclerosis, CNS, and cardiovascular diseases). For example, the involvement of MMP-2 and -9 (both gelatinases) and MMP-7 (matrilysin) in colorectal cancers (21) indicates these MMP activities as possible biomarkers for disease progression (22–26). Moreover, Massagué et al. have validated (by RNA interference) the cooperative action of an EGFR ligand, COX-2, MMP-1, and MMP-2 in human breast cell metastasis using implanted tumors in mice (27) and have replicated interference of this cooperation using a combination of EGFR and COX-2 inhibitors (28). The added value (to the paired EGFR and COX-2 inhibitors) of a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor was less evident in this study (28), possibly due to the simultaneous antagonism of MMP-dependent inhibition of metastasis and of MMP-promotion of metastasis, by the broad-spectrum inhibitor (ilomastat, GM6001) that was used. It is precisely this dilemma – a lack of specificity in the available MMP reagent – that is a stimulus to the current research continuing to examine the value of the MMPs as therapeutic targets.

The experimental evaluation of enzyme selectivity may be made in terms of substrate or inhibitor profiling, coupled to an experimental method for assessment of the enzyme–substrate or enzyme–inhibitor recognition. The variety of approaches – both in terms of reagent and method of analysis – reported for the MMPs is astonishing. Among the questions addressed by these approaches were the following: How can substrate or inhibitor arrays be used to characterize the MMP sub-type? How can advanced analytical methods characterize the endogenous substrates recognized by the MMPs within cells? What new methods are available to quantify the amount of active MMP in the cell? In different but complementary ways, these approaches are efforts toward the improved and specific profiling of the presence and the catalytic character of MMP sub-types.

As the first three of the above four questions are more completely addressed in the companion chapters within this volume, we here only cite the recent advances in these areas. The ability to construct extraordinarily large peptide arrays for the determination of protease specificity (29) has been used by Thomas et al. (30) to validate an endopeptidase profiling library with MMP-12 and MMP-13. Overall et al. (31, 32) and Fields et al. (33–36) have examined MMP recognition of collagen as a triple helical peptide substrate. These concepts have been applied to new MMP inhibitor design (37). The methodologies for MMP assay (38) have expanded to include increasingly sophisticated methods for cell, tissue, and animal imaging (39–44). Among the recent methods reported for improved evaluation of MMP activity in vitro and in vivo are zymographic (45–47), Raman (48), IR (49–51), MRI (52–55), xenon NMR (56), radiochemical (57–62), PET (63–67), MMP-triggered magnetic nanoparticle self-assembly (68), and luminescent (40, 69–76) analyses. Increasingly refined MMP sub-type-selective substrates (for MMPs-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -9, -10, -12, -13, and -14) for FRET fluorescent assay are commercially available (77). Using porous silicon photonic film overlayed (spin-coated) with label-free gelatin as an MMP-2 substrate, Gao et al. (78) described a highly sensitive and dose-responsive (detecting 0.1 to 1000 ng mL–1 MMP in μL drops) assay, which they estimated to be 100-fold more sensitive than standard MMP zymography and to fulfill the practical requirements for diagnostic MMP detection (rapid, simple, dose responsive, and inexpensive). With respect to the identification of endogenous MMP substrates – a matter of increasing relevance, given the new appreciation of the MMPs as having both anti- and pro-angiogenic activity – Overall et al. have developed mass spectrometry methods to evaluate the cellular substrates (the MMP degradome) recognized by the MMPs (79–84).

2. Methods for MMP Activity Profiling

The final question is that of MMP profiling by the use of inhibitors. The foundational principle to this approach is the use of functional groups that target the catalytic zinc of these enzymes (ZBG, a zinc-binding group) placed into a peptidomimetic structure biased toward selective MMP recognition. The key aspect of this approach is the use of a ZBG-containing MMP inhibitor with intrinsic specificity. While considerable progress has been made toward the structure-based optimization of MMP inhibitor structure (85–89), the creation of MMP sub-type-selective structure is extraordinarily challenging and still remains largely vested in empirical experiment. For this reason, and also recognizing that one of the most powerful of the ZBGs (the hydroxamate) is easily incorporated by the standard methods of peptide array synthesis, large peptidomimetic inhibitor libraries (arrays) have been prepared for MMP profiling.

Yao et al. have developed hydroxamate inhibitor microarrays (small molecule microarrays, SMM) for rapid in vitro metalloprotease profiling (“fingerprinting”) (90–92). Their initial 1400-member library used a diversified tripeptide motif having an ilomastat-type β-substituted succinyl hydroxamate C terminus and a biotinylated N terminus to allow streptavidin capture. Comparative SAR (activity, specificity, potency, hierarchical clustering) was assessed with respect to inhibition of bacterial collagenase, carboxypeptidase, thermolysin, and anthrax lethal factor as enzyme targets. Detailed and complete protocols for the implementation of a 400-member biotinylated P1′-leucine sub-set of this library for MMP-7 profiling (including a full description of the synthesis of the β-isopropyl-substituted succinyl hydroxamate warhead, the split-pool solid-phase peptide synthesis of the library, and the use of either microplate or microarray analysis) are described by the Yao group (93). A companion protocol (exploiting the P1′-leucine-based succinyl hydroxamate warhead, but using Click-derived triazole diversification) is also described (94, 95). In this latter protocol, the β-substituted succinyl hydroxamate is coupled with propargylamine to generate the terminal alkyne necessary for subsequent Click diversification using azidecontaining secondary binders. Direct screening against the target enzyme is done by microplate assay. Complementary hydroxamate inhibitor array efforts are described by Flipo et al. for screening against neutral aminopeptidase (96) and by Johnson et al. (97) for screening against anthrax lethal factor. Vegas et al. (98) describe the use of fluorous methodology for hydroxamate screening against histone deacetylase.

Cravatt et al. (99–102) describe the creation of inhibitor arrays for the activity-based enzyme profiling (ABPP) of metalloproteases. The objectives of the ABPP approach are the identification of an enzyme-selective inhibitor within the array and subsequent quantitative evaluation of the activity in tissue (crude proteomes) using the inhibitor. Absolute selectivity toward a particular enzyme is not necessary, as will be evident from this summary of the ABPP method. The array is based around an inhibitor structure that confers a structural bias (such as a ZBG for the MMPs) for recognition as an inhibitor by the target enzyme. The ZBG is diversified by the addition of secondary (an amino acid) or tertiary (a dipeptide) structure. The probe structure is completed by the addition of a photoaffinity label to enable covalent linkage of the inhibitor to the target enzyme(s) and a biotin tag to enable recovery of the enzyme–inhibitor pair(s) from the crude proteome. Identification of the enzyme(s) is done by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) assignment of the tryptic peptides obtained from the recovered enzyme. The power of this method was proven by MMP profiling (103–105). Specifically, Saghatelian et al. (103) identified GM6001 (ilomastat) – one of the early MMP inhibitors clinically evaluated for anticancer activity – as not merely a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor but as an inhibitor within the neprilysin, aminopeptidase, and dipeptidylpeptidase metalloprotease families. Using β-monosubstituted and α,β-disubstituted succinyl hydroxamates as the zinc-binding group (ZBG), and benzophenone photoaffinity labeling, Sieber et al. (106) have compared relative expression of several subfamilies of the zinc metalloprotease superfamily (107, 108) in an invasive (MUM-2B) and in a non-invasive (MUM-2C) human melanoma cancer cell line. By using an alkyne-functionalized terminus in the inhibitor structure, to allow post-photoaffinity labeling addition of the biotin tag by Click derivatization, two enzymes of the zinc metalloprotease superfamily (alanyl aminopeptidase and neprilysin) were seen to be expressed in significantly greater amounts in the invasive cell line. The sensitivity of this assay for MMPs, determined by progressive addition of MMP into a constant background of proteome, was approximately 0.25–2.5 μg MMP per milligram of proteome using gel-based detection. LC/MS-MS detection of the MMP improved the sensitivity of MMP detection (compared to the gel assay method) by 5–50-fold. Sieber et al. (106) make several important observations concerning the implementation of affinity probes for proteome analysis. Separate steps for photoaffinity labeling of the enzyme–inhibitor complex, and subsequent incorporation of the functional group to be used for detection (such as biotin or a fluorophore), gave probes with better performance than did probes having the detection group pre-incorporated into the structure. The reason for this is the significant modification to the inhibitor structure by large mass of the detection group itself, as opposed to the small and (otherwise) unreactive alkyne terminus used for Click-based addition of the detection group in the two-step tag incorporation method. Moreover, Cravatt et al. emphasize the necessity of the control experiment to establish the proteome background (non-specific protein binders). For Click-based incorporation of the detection group, the control used is the cognate probe structure, wherein the alkyne functional group is replaced by an alkane functional group. The alkane-substituted probe will bind to the target, but cannot participate in the Click functionalization, and hence the target enzyme should not appear in avidin pull-down. For example, in the assay of the MMPs, one MMP sub-type – MMP-14 – was found to be problematic for its non-specific appearance. The Cravatt laboratory has given detailed protocols describing the further refinement of this activity-based protein profiling method, wherein the N-terminal biotinylated tag is separated from its C-terminal azide by an octapeptide spacer (109). This octapeptide encodes the unusual Gln-Gly cleavage site of the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease. This method – termed tandem orthogonal proteolysis (TOP)-ABPP – involves photoaffinity labeling of the enzyme by the probe, biotin tagging of the probe–enzyme complex by Click azide–alkyne cycloaddition, avidin capture, trypsin digestion, and final TEV release of the covalently labeled tryptic peptide (by the photoaffinity label) for LC/MS-MS identification (109). The implementation of TOP-ABPP has not yet been applied to the MMPs.

Overkleeft et al. (110) have independently reported the solid-phase synthesis of MMP hydroxamate inhibitors for use in MMP profiling. Complete synthetic methods are given for the synthesis of the P1′-leucine-based succinyl hydroxamate library, the incorporation of a trifluoromethyldiazirene photoaffinity label, and the addition to the N terminus of either a boratriazaindacene fluorophore or a biotin tag. In vitro validation (successful photoaffinity labeling) of the most potent inhibitor using MMP-12 (IC50 = 4 nM) and ADAM-17 (IC50 = 21 nM) was shown by strong streptavidin labeling of the ADAM-10 band in the SDS-PAGE gel.

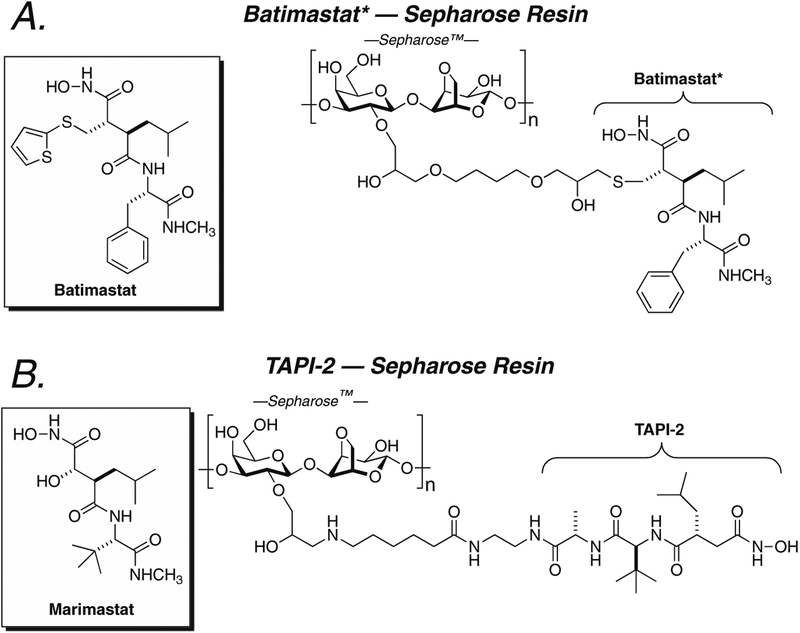

A conceptually identical, but experimentally quite different, approach to the determination of active MMP is that the cell or the tissue uses an MMP inhibitor covalently attached to an insoluble support (resin). The objective – the determination of the MMP sub-type and the total activity of that sub-type present in the cell – is identical to that of the ABPP method. The advantage of covalent immobilization of the inhibitor is its ability to capture and concentrate the MMP, enabling the use of different assay methods for the characterization of the MMP (111–114). Two implementations of this approach have recently been described for the MMPs. Hesek et al. prepared an MMP capture resin based on the attachment of a structurally modified, broad-spectrum hydroxamate MMP inhibitor to a Sepharose resin (115). Examination of the structure of the MMP–batimastat complex indicated solvent exposure of the thienyl ring. Replacement of this thiophene with a cysteine-like thiomethyl substituent enabled attachment of the modified inhibitor to epoxy–Sepharose, using the thiolate of the modified inhibitor to open the epoxide functional group of the resin. The structure of batimastat and the batimastat-type affinity resin is shown in Fig. 27.1a. This resin has high capacity (0.4 μmol of ligand per gram of dry resin). Extensive in vitro validation of this resin indicated specificity for recovery of active MMP-2 and MMP-9. Neither the zymogen form of these enzymes nor the TIMP complex of these enzymes is retained by the resin. The flow-through of active MMPs from the resin is negligible, and the resin-bound active enzyme is stable to extensive column washing. Release of the enzyme from the resin is accomplished with reducing SDS sample buffer, or with buffer containing marimastat (also a broad-spectrum hydroxamate MMP inhibitor). Validation of the resin with biological samples, using tissue extracts prepared from human breast and laryngeal carcinomas, recovered both MMP-2 and MMP-14 from the extracts (whether additional MMPs were present was not determined). The successful application of this resin to the recovery of active MMP-2 present in breast and laryngeal carcinomas has been thoroughly described, using gelatin zymography as a readout of the free MMP activity in these tissues (116). Additionally, this same resin captured the TIMP-free MMP-14 present in detergent-free breast carcinoma extracts (117). Zucker and Cao (114) provide an excellent perspective on the importance of the selective determination of active MMP in tumor tissue, using MMP inhibitor-tethered resins, to the understanding of the role of the MMPs in the tumor microenvironment and to the development of improved MMP inhibitor therapy.

Fig. 27.1.

a. Structure of batimastat (left) and the structurally modified analog of batimastat (right) that is attached, as a broad-spectrum MMP affinity inhibitor, to epoxy–Sepharose as described by Hesek et al. (115, 116). b. Structure of marimastat (left) and the related TAPI-2 structure (right) attached to NHS–Sepharose as described by Freije and Bischoff (118).

The enrichment of active MMP from biological samples is also described by Bischoff et al., also using Sepharose immobilization of an alternative broad-spectrum hydroxamate (TAPI-2) inhibitor of the MMPs (118). A free amine at the N terminus forms a stable amide bond with NHS–Sepharose to give the affinity resin (Fig. 27.1b). Elution of the MMP from the resin uses an EDTA-containing elution buffer. Subsequent reports from the Bischoff laboratory provide extensive validation of their TAPI-2 resin (119, 120). Control experiments indicate that this resin efficiently captures and concentrates MMPs-1, -7, -8, -10, -12, and -13 with extraction yields exceeding 96%. Otherwise undetectable quantities of MMP-9 in synovial fluid, obtained from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, were enriched sufficiently to allow facile gelatin zymography detection of the MMP-9 activity (119). The interface of the TAPI-2 column with an immobilized tryptic reactor (thus allowing online tryptic digestion) enabled MS detection and analysis of the tryptic peptides of recombinant MMP-12-spiked urine (120). The performance of this resin indicates high concentrative ability of the MMP from a biological fluid and high sensitivity of the MMPs (using MMP-12 as the analyte). MMP-12 at picomole levels was detected easily (using 0.5 mL urine containing 8 nM MMP-12) (120). This result indicates the likelihood that this method could be developed for MMP-12 detection as a possible biomarker for malignant bladder cancer.

The methods for the chemical synthesis of both the Hesekmodified batimastat resin and the Bischoff TAPI-2 resins are fully described. Moreover, detailed protocols for the liquid-phase chemical synthesis of very closely related inhibitors are given by Yao (93, 95) and for solid-phase synthesis are given by Overkleeft et al. (110). Nonetheless, all of these syntheses are labor intensive. The Hesek resin uses a neutral thioether functional group for the attachment of its ligand to the resin. The use of a neutral (uncharged) linker is known to minimize the non-specific capture of proteins by the resin itself acting as an ion-exchange resin. Preliminary experiments with a Hesek resin that uses the same structure but with a carboxylate ZBG, instead of a hydroxamate ZBG, are equally successful toward MMP capture from tissue. While the carboxylate ZBG typically gives less potent inhibitors than does the hydroxamate ZBG, its use as an affinity ligand may further improve MMP selectivity during these extractions, by suppression of non-specific enzyme capture. The TAPI-2 structure used in the Bischoff resin is commercially available but is very expensive. TAPI-2 attaches to NHS-activated Sepharose, which has a non-neutral (albeit weakly basic) linker between the caproate NHS active ester and the Sepharose. Hence, appreciable limitations remain for both the ABPP and the affinity resin approaches to MMP profiling. The former method requires access to a mass spectrometer capable of peptide MS/MS analysis. The latter method requires extensive up-front organic synthesis for resin preparation.

A final method for MMP activity profiling is the use of the MMP-selective inhibitor. All of the methods discussed thus far use a hydroxamate ZBG within a peptidomimetic motif that confers selectivity, but by no means specificity, for the MMP zinc metalloproteases. The use of a non-selective inhibitor [such as ilomastat, as is used in the Cravatt ABPP (106); batimastat, as is used for the Hesek resin (116); or TAPI-2, as is used for the Bischoff resin (118, 120)] has the advantage of the simultaneous profiling of many MMP sub-types. There can also be no doubt that extension of the ABPP method to determine the total MMP inventory (active and inactive MMP) of a cell is well within the power of the ABPP methods, albeit with the requirement for sophisticated MS analysis. Whilst this analysis will greatly increase our understanding of the MMP proteome (101) and complement our understanding of the MMP degradome (84, 121), this increased understanding does not directly connect to a chemical strategy for the selective inhibition of the MMP activity contributing to the disease. The power of the hydroxamate ZBG is its potency for zinc chelation and the ease of its incorporation by solid-phase synthesis into diverse peptidomimetic inhibitors of the MMPs. The limitation of the hydroxamate is its inadequacy as a functional group for drug development. As greater appreciation of the shortcomings of the hydroxamate as a ZBG has followed the abandonment of early generation hydroxamate MMP inhibitors as clinical candidates (5, 7), the search for more drug-compatible ZBGs has coincided with diminished interest in drug development against the MMPs. Nonetheless, there is an outstanding example of the power of a selective inhibitor for MMP activity profiling. The MMP inhibitor SB-3CT uses a thiirane (a three-membered, sulfur-containing ring), and not a hydroxamate, as a latent ZBG. Mechanism-based activation of the thiirane is accomplished only by the gelatinase (MMP-2 and MMP-9) MMP subclass (122). Moreover, the synthesis of members of the SB-3CT class is very straightforward (123). The gelatinase specificity of SB-3CT has allowed it to implicate gelatinase involvement in a number of animal models of human disease, including apoptosis following transient focal cerebral ischemia (124), T-cell lymphoma metastasis to the lung (125), retinal ganglion cell axon guidance (126), MMP-2 mediation of ethanol-induced invasion of mammary epithelial cells (127), β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated apoptosis in myocytes (128), prostate cancer metastasis to the bone (129, 130), and Aβ(1–40)-induced secretion of MMP-9 (131). Conversely, the ineffectiveness of SB-3CT in a model of collagen I invasion by ovarian cancer cell implicated MMP-14 involvement in this metastatic event (132).

A second non-hydroxamate ZBG has also been evaluated for possible MMP sub-type selectivity. Using a novel phosphinate insert, Dive et al. (133–137) have prepared peptidomimetic inhibitors with MMP-11 and MMP-12 selectivity. Using a high specific activity (8 Ci mmol–1) 3H-radiolabel, phosphinate peptidomimetics with an aryl azide photoaffinity label were synthesized. Following UV irradiation, 1D SDS-PAGE autoradiography identified the threshold detection quantity of MMP-12 to be 50 pg (2.5 fmol of MMP-12 at 100 pM concentration) (138). Among the other MMPs with similar active sites as MMP-12, MMP-2, -12, -13, and -14 were comparably labeled, while the labeling of MMP-3, -8, -9, and -11 was several-fold poorer (138). These data indicate that the level of MMP sub-type selectivity necessary for sub-type profiling has yet to be attained with this phosphinate insert.

3. Summary

The challenge of MMP activity profiling is being addressed by a convergence of improved synthetic methodology and increasingly more sophisticated analytical methods, with an increasingly better understanding of the complex roles of the MMPs in disease. The power of these methods, and the quality of the instructions to implement the methods, is evident. These methods are robust. They are not, however, routine. The enabling investment – whether in synthetic chemistry or in instrumentation – to perform MMP activity profiling is substantial. A substantial investment is always required to implement new technologies. The extraordinary breadth of the recent approaches, and the vigor of the inquiry, indicates recognition of the importance that these technologies advance to a level of robustness and routine. Whether by the perseverance of the single laboratory or by multi-laboratory collaboration, the methods cited in this chapter will further elucidate the MMP activity profile. The value of this information for disease diagnostics, and as guidance to rekindle medicinal chemistry and pharmacological interest in MMP inhibition for the treatment of disease, cannot be underestimated.

References

- 1.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, and Matrisian LM (2002) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science 295, 2387–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overall CM and Lopez-Otin C (2002) Strategies for MMP inhibition in cancer: innovations for the post-trial era. Nat Rev Cancer 2, 657–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fingleton B (2003) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors for cancer therapy: the current situation and future prospects. Expert Opin Ther Targets 7, 385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fingleton B (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases: roles in cancer and metastasis. Front Biosci 11, 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher JF and Mobashery S (2006) Recent advances in MMP inhibitor design. Cancer Metastasis Rev 25, 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Otin C and Matrisian LM (2007) Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer 7, 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overall CM and Kleifeld O (2006) Towards third generation matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer 94, 941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sang QXA, Jin Y, Newcomer RG, Monroe SC, Fang X, Hurst DR, Lee S, Cao Q, and Schwartz MA (2006) MMP inhibitors as prospective agents for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and neoplastic diseases. Curr Top Med Chem 6, 289–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk B (2006) Targeting proteases: successes, failures and future prospects. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deryugina EI and Quigley JP (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 25, 9–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta GP and Massagué J (2006) Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell 127, 679–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lah TT, Duran Alonso MB, and Van Noorden CJ (2006) Antiprotease therapy in cancer: hot or not? Expert Opin Biol Ther 6, 257–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, and Maley CC (2006) Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overall CM and Kleifeld O (2006) Tumour microenvironment - opinion: validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cauwe B, Van den Steen PE, and Opdenakker G (2007) The biochemical, biological, and pathological kaleidoscope of cell surface substrates processed by matrix metalloproteinases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 42, 113–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Partridge JJ, Madsen MA, Ardi VC, Papagiannakopoulos T, Kupriyanova TA, Quigley JP, and Deryugina EI (2007) Functional analysis of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases differentially expressed by variants of human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma exhibiting high and low levels of intravasation and metastasis. J Biol Chem 282, 35964–35977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin MD and Matrisian LM (2007) The other side of MMPs: Protective roles in tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26, 717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen DX and Massagué J (2007) Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genet 8, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahai E (2007) Illuminating the metastatic process. Nat Rev Cancer 7, 737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincenti MP and Brinckerhoff CE (2007) Signal transduction and cell-type specific regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression: can MMPs be good for you? J Cell Physiol 213, 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagenaar-Miller RA, Gorden L, and Matrisian LM (2004) Matrix metalloproteinases in colorectal cancer: is it worth talking about? Cancer Metastasis Rev 23, 119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho YB, Lee WY, Song SY, Shin HJ, Yun SH, and Chun HK (2007) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity is associated with poor prognosis in T3–T4 node-negative colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol 38, 1603–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorden DL, Fingleton B, Crawford HC, Jansen DE, Lepage M, and Matrisian LM (2007) Resident stromal cell-derived MMP-9 promotes the growth of colorectal metastases in the liver microenvironment. Int J Cancer 121, 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilska M, Roberts PJ, Collan YU, Laine VJ, Kossi J, Hirsimaki P, Rahkonen O, and Laato M (2007) Prognostic significance of MMPs-1, -2, -7 and -13 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1, -2, -3 and -4 in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 121, 714–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst NG, Stocken DD, Wilson S, Keh C, Wakelam MJ, and Ismail T (2007) Elevated serum MMP-9 concentration predicts the presence of colorectal neoplasia in symptomatic patients. Br J Cancer 97, 971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maurel J, Nadal C, Garcia-Albeniz X, Gallego R, Carcereny E, Almendro V, Marmol M, Gallardo E, Maria Auge J, Longaron R, Martinez-Fernandez A, Molina R, Castells A, and Gascon P (2007) Serum MMP-7 levels identifies poor prognosis advanced colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer 121, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Padua D, Bos P, Nguyen DX, Nuyten D, Kreike B, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Ishwaran H, Foekens JA, van de Vijver M, and Massagué J (2007) Lung metastasis genes couple breast tumor size and metastatic spread. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 6740–6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta GP, Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, Bos PD, Kim JY, Nadal C, Gomis RR, Manova-Todorova K, and Massagué J (2007) Mediators of vascular remodelling co-opted for sequential steps in lung metastasis. Nature 446, 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kofoed J and Reymond JL (2007) Identification of protease substrates by combinatorial profiling on TentaGel beads. Chem Commun (Camb) 4453–4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas DA, Francis P, Smith C, Ratcliffe S, Ede NJ, Kay C, Wayne G, Martin SL, Moore K, Amour A, and Hooper NM (2006) A broad-spectrum fluorescence-based peptide library for the rapid identification of protease substrates. Proteomics 6, 2112–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tam EM, Moore TR, Butler GS, and Overall CM (2004) Characterization of the distinct collagen binding, helicase and cleavage mechanisms of MMP-2 and -14 (gelatinase A and MT1-MMP): the differential roles of the MMP hemopexin c domains and the MMP-2 fibronectin type II modules in collagen triple helicase activities. J Biol Chem 279, 43336–43344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelman GR, Morrison CJ, and Overall CM (2005) Pivotal molecular determinants of peptidic and collagen triple helicase activities reside in the S3′ subsite of matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8): the role of hydrogen bonding potential of ASN188 and TYR189 and the connecting cis bond. J Biol Chem 280, 2370–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauer-Fields JL, Sritharan T, Stack MS, Nagase H, and Fields GB (2003) Selective hydrolysis of triple-helical substrates by MMP-2 and -9. J Biol Chem 278, 18140–18145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Wang Y, Lauer-Fields JL, Fields GB, and Steffensen B (2004) Contributions of the MMP-2 collagen binding domain to gelatin cleavage: substrate binding via the collagen binding domain is required for hydrolysis of gelatin but not short peptides. Matrix Biol 23, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minond D, Lauer-Fields JL, Cudic M, Overall CM, Pei D, Brew K, Visse R, Nagase H, and Fields GB (2006) The roles of substrate thermal stability and P2 and P1′ subsite identity on matrix metalloproteinase triple-helical peptidase activity and collagen specificity. J Biol Chem 281, 38302–38313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minond D, Lauer-Fields JL, Cudic M, Overall CM, Pei D, Brew K, Moss ML, and Fields GB (2007) Differentiation of secreted and membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase activities based on substitutions and interruptions of triple-helical sequences. Biochemistry 46, 3724–3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauer-Fields J, Brew K, Whitehead JK, Li S, Hammer RP, and Fields GB (2007) Triple-helical transition state analogues: a new class of selective MMP inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc 129, 10408–10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombard C, Saulnier J, and Wallach J (2005) Assays of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) activities: a review. Biochimie 87, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntyre JO and Matrisian LM (2003) Molecular imaging of proteolytic activity in cancer. J Cell Biochem 90, 1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McIntyre JO, Fingleton B, Wells KS, Piston DW, Lynch CC, Gautam S, and Matrisian LM (2004) Development of a novel fluorogenic proteolytic beacon for in vivo detection and imaging of tumour-associated MMP-7 activity. Biochem J 377, 617–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf K and Friedl P (2005) Functional imaging of pericellular proteolysis in cancer cell invasion. Biochimie 87, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, So MK, and Rao J (2006) Protease-modulated cellular uptake of quantum dots. Nano Lett 6, 1988–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fonovic M and Bogyo M (2007) Activity based probes for proteases: applications to biomarker discovery, molecular imaging and drug screening. Curr Pharm Des 13, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanabe K, Zhang Z, Ito T, Hatta H, and Nishimoto S (2007) Current molecular design of intelligent drugs and imaging probes targeting tumor-specific microenvironments. Org Biomol Chem 5, 3745–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakuraba I, Hatakeyama J, Hatakeyama Y, Takahashi I, Mayanagi H, and Sasano Y (2006) The MMP activity in developing rat molar roots and incisors demonstrated by in situ zymography. J Mol Histol 37, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans RD and Itoh Y (2007) Analyses of MT1-MMP activity in cells. Methods Mol Med 135, 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eissa S, Ali-Labib R, Swellam M, Bassiony M, Tash F, and El-Zayat TM (2007) Noninvasive diagnosis of bladder cancer by detection of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) and their inhibitor (TIMP-2) in urine. Eur Urol 52, 1388–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amharref N, Beljebbar A, Dukic S, Venteo L, Schneider L, Pluot M, and Manfait M (2007) Discriminating healthy from tumor and necrosis tissue in rat brain tissue samples by Raman spectral imaging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768, 2605–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang T, Olson ES, Nguyen QT, Roy M, Jennings PA, and Tsien RY (2004) Tumor imaging by means of proteolytic activation of cell-penetrating peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 17867–17872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pham W, Choi Y, Weissleder R, and Tung CH (2004) Developing a peptide-based near-infrared molecular probe for protease sensing. Bioconjug Chem 15, 1403–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Tung CH, Allport JR, Chen S, Weissleder R, and Huang PL (2005) Near-infrared fluorescent imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 111, 1800–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiart M, Fournier LS, Novikov VY, Shames DM, Roberts TP, Fu Y, Shalinsky DR, and Brasch RC (2004) MRI detects early changes in microvascular permeability in xenograft tumors after treatment with the matrix metalloprotease inhibitor Prinomastat. Technol Cancer Res Treat 3, 377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sood RR, Taheri S, Candelario-Jalil E, Estrada EY, and Rosenberg GA (2008) Early beneficial effect of MMP inhibition on blood-brain barrier permeability as measured by MRI countered by impaired long-term recovery after stroke in rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tamai M, Kawakami A, Uetani M, Takao S, Tanaka F, Fujikawa K, Aramaki T, Nakamura H, Iwanaga N, Izumi Y, Arima K, Aratake K, Kamachi M, Huang M, Origuchi T, Ida H, Aoyagi K, and Eguchi K (2007) Bone edema determined by MRI reflects severe disease status in patients with early-stage rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 34, 2154–2157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lepage M, Dow WC, Melchior M, You Y, Fingleton B, Quarles CC, Pepin C, Gore JC, Matrisian LM, and McIntyre JO (2007) Noninvasive detection of matrix metalloproteinase activity in vivo using a novel MRI contrast agent with a solubility switch. Mol Imaging 6, 393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei Q, Seward GK, Hill PA, Patton B, Dimitrov IE, Kuzma NN, and Dmochowski IJ (2006) Designing 129Xe NMR biosensors for MMP detection. J Am Chem Soc 128, 13274–13283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kopka K, Breyholz HJ, Wagner S, Law MP, Riemann B, Schroer S, Trub M, Guilbert B, Levkau B, Schober O, and Schafers M (2004) Synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation of new radioiodinated MMP inhibitors for imaging MMP activity in vivo. Nucl Med Biol 31, 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schafers M, Riemann B, Kopka K, Breyholz HJ, Wagner S, Schafers KP, Law MP, Schober O, and Levkau B (2004) Scintigraphic imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activity in the arterial wall in vivo. Circulation 109, 2554–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oltenfreiter R, Staelens L, Hillaert U, Heremans A, Noel A, Frankenne F, and Slegers G (2005) Synthesis, radiosynthesis, in vitro and preliminary in vivo evaluation of biphenyl carboxylic and hydroxamic matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors as potential tumor imaging agents. Appl Radiat Isotopes 62, 903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Medina OP, Kairemo K, Valtanen H, Kangasniemi A, Kaukinen S, Ahonen I, Permi P, Annila A, Sneck M, Holopainen JM, Karonen SL, Kinnunen PK, and Koivunen E (2005) Radionuclide imaging of tumor xenografts in mice using a gelatinase-targeting peptide. Anticancer Res 25, 33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van de Wiele C and Oltenfreiter R (2006) Imaging probes targeting MMP. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 21, 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanaoka H, Mukai T, Habashita S, Asano D, Ogawa K, Kuroda Y, Akizawa H, Iida Y, Endo K, Saga T, and Saji H (2007) Chemical design of a radiolabeled gelatinase inhibitor peptide for the imaging of gelatinase activity in tumors. Nucl Med Biol 34, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng QH, Fei X, DeGrado TR, Wang JQ, Stone KL, Martinez TD, Gay DJ, Baity WL, Mock BH, Glick-Wilson BE, Sullivan ML, Miller KD, Sledge GW, and Hutchins GD (2003) Synthesis, biodistribution and micro-PET imaging of a potential cancer biomarker carbon-11 labeled MMP inhibitor (2R)-2-[[4-(6-fluorohex-1-ynyl)phenyl]sulfonylamino]-3-methylbutyric acid [11C]methyl ester. Nucl Med Biol 30, 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng QH, Fei X, Liu X, Wang JQ, Stone KL, Martinez TD, Gay DJ, Baity WL, Miller KD, Sledge GW, and Hutchins GD (2004) Comparative studies of potential cancer biomarkers carbon-11 labeled MMP inhibitors (S)-2-(4′-[11C]methoxybiphenyl-4-sulfonylamino)-3-methylbutyric acid and N-hydroxy-(R)-2-[[(4′-[11C]methoxyphenyl)sulfonyl] benzylamino]-3-methylbut anamide. Nucl Med Biol 31, 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Breyholz HJ, Schafers M, Wagner S, Holtke C, Faust A, Rabeneck H, Levkau B, Schober O, and Kopka K (2005) C-5-disubstituted barbiturates as potential molecular probes for noninvasive matrix metalloproteinase imaging. J Med Chem 48, 3400–3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wagner S, Breyholz HJ, Faust A, Holtke C, Levkau B, Schober O, Schafers M, and Kopka K (2006) Molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinases in vivo using small molecule inhibitors for SPECT and PET. Curr Med Chem 13, 2819–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wagner S, Breyholz HJ, Law MP, Faust A, Holtke C, Schroer S, Haufe G, Levkau B, Schober O, Schafers M, and Kopka K (2007) Novel fluorinated derivatives of the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors N-Hydroxy-2(R)-[[(4-methoxyphenyl)sulfonyl](benzyl)- and (3-picolyl)-amino]-3-methyl-butanamide as potential tools for the molecular imaging of activated MMPs with PET. J Med Chem 50, 5752–5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris TJ, von Maltzahn G, Derfus AM, Ruoslahti E, and Bhatia SN (2006) Proteolytic actuation of nanoparticle self-assembly. Angew Chem Int Ed 45, 3161–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.George J, Teear ML, Norey CG, and Burns DD (2003) Evaluation of an imaging platform during the development of a FRET protease assay. J Biomol Screen 8, 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fingleton B, Menon R, Carter KJ, Overstreet PD, Hachey DL, Matrisian LM, and McIntyre JO (2004) Proteinase activity in human and murine saliva as a biomarker for proteinase inhibitor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res 10, 7865–7874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berthelot T, Talbot JC, Lain G, Deleris G, and Latxague L (2005) Synthesis of Nepsilon-(7-diethylaminocoumarin-3-carboxyl)- and N epsilon-(7-methoxycoumarin-3-carboxyl)-L-Fmoc lysine as tools for protease cleavage detection by fluorescence. J Pept Sci 11, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao H, Zhang Y, Xiao F, Xia Z, and Rao J (2007) Quantum dot/bioluminescence resonance energy transfer based highly sensitive detection of proteases. Angew Chem Int Ed 46, 4346–4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zheng G, Chen J, Stefflova K, Jarvi M, Li H, and Wilson BC (2007) Photodynamic molecular beacon as an activatable photosensitizer based on protease-controlled singlet oxygen quenching and activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 8989–8994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kovar JL, Simpson MA, Schutz-Geschwender A, and Olive DM (2007) A systematic approach to the development of fluorescent contrast agents for optical imaging of mouse cancer models. Anal Biochem 367, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang J, Zhang Z, Lin J, Lu J, Liu BF, Zeng S, and Luo Q (2007) Detection of MMP activity in living cells by a genetically encoded surface-displayed FRET sensor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773, 400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Go K, Garcia R, and Villarreal FJ (2008) Fluorescent method for detection of cleaved collagens using O-phthaldialdehyde (OPA). J Biochem Biophys Methods doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rakhmanova V, Meyer R, and Tong X (2007) New substrates for FRET-based Assays. Genet Eng Biotechnol News 27, 40 (15 Oct 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao L, Mbonu N, Cao L, and Gao D (2008) Label-free colorimetric detection of gelatinases on nanoporous silicon photonic films. Anal Chem doi: 10.1021/ac701870y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Overall CM and Dean RA (2006) Degradomics: systems biology of the protease web. pleiotropic roles of MMPs in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 25, 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Butler GS and Overall CM (2007) Proteomic validation of protease drug targets: pharmacoproteomics of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor drugs using isotope-coded affinity tag labelling and tandem mass spectrometry. Curr Pharm Des 13, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dean RA and Overall CM (2007) Proteomics discovery of metalloproteinase substrates in the cellular context by iTRAQ labeling reveals a diverse MMP-2 substrate degradome. Mol Cell Proteomics 6, 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dean RA, Butler GS, Hamma-Kourbali Y, Delbe J, Brigstock DR, Courty J, and Overall CM (2007) Identification of candidate angiogenic inhibitors processed by MMP-2 in cell-based proteomic screens: disruption of VEGF/heparin affin regulatory peptide (pleiotrophin) and VEGF/Connective tissue growth factor angiogenic inhibitory complexes by MMP-2 proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol 27, 8454–8465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schilling O and Overall CM (2007) Proteomic discovery of protease substrates. Curr Opin Chem Biol 11, 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Overall CM and Blobel CP (2007) In search of partners: linking extracellular proteases to substrates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rao BG (2005) Recent developments in the design of specific MMP inhibitors aided by structural and computational studies. Curr Pharm Des 11, 295–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bertini I, Calderone V, Cosenza M, Fragai M, Lee YM, Luchinat C, Mangani S, Terni B, and Turano P (2005) Conformational variability of MMPs: beyond a single 3D structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 5334–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertini I, Fragai M, Giachetti A, Luchinat C, Maletta M, Parigi G, and Yeo KJ (2005) Combining in silico tools and NMR data to validate protein-ligand structural models: application to MMPs. J Med Chem 48, 7544–7559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tochowicz A, Maskos K, Huber R, Oltenfreiter R, Dive V, Yiotakis A, Zanda M, Bode W, and Goettig P (2007) Crystal structures of MMP-9 complexes with five inhibitors: contribution of the flexible Arg424 side-chain to selectivity. J Mol Biol 371, 989–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bertini I, Calderone V, Fragai M, Giachetti A, Loconte M, Luchinat C, Maletta M, Nativi C, and Yeo KJ (2007) Exploring the subtleties of drug-receptor interactions: the case of MMPs. J Am Chem Soc 129, 2466–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Panicker RC, Chattopadhaya S, and Yao SQ (2006) Advanced analytical tools in proteomics. Anal Chim Acta 556, 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun H, Panicker RC, and Yao SQ (2007) Activity based fingerprinting of proteases using FRET peptides. Biopolymers 88, 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Uttamchandani M, Lee WL, Wang J, and Yao SQ (2007) Quantitative inhibitor fingerprinting of metalloproteases using small molecule microarrays. J Am Chem Soc 129, 13110–13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee WL, Li J, Uttamchandani M, Sun H, and Yao SQ (2007) Inhibitor fingerprinting of metalloproteases using microplate and microarray platforms: an enabling technology in Catalomics. Nat Protoc 2, 2126–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang J, Uttamchandani M, Li J, Hu M, and Yao SQ (2006) “Click” synthesis of small molecule probes for activity-based fingerprinting of matrix metalloproteases. Chem Commun (Camb) 3783–3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Srinivasan R, Li J, Ng SL, Kalesh KA, and Yao SQ (2007) Methods of using click chemistry in the discovery of enzyme inhibitors. Nat Protoc 2, 2655–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Flipo M, Beghyn T, Charton J, Leroux VA, Deprez BP, and Deprez-Poulain RF (2007) A library of novel hydroxamic acids targeting the metallo-protease family: design, parallel synthesis and screening. Bioorg Med Chem 15, 63–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johnson SL, Chen LH, and Pellecchia M (2007) A high-throughput screening approach to anthrax lethal factor inhibition. Bioorg Chem 35, 306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vegas AJ, Bradner JE, Tang W, McPherson OM, Greenberg EF, Koehler AN, and Schreiber SL (2007) Fluorous-based small-molecule microarrays for the discovery of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed 46, 7960–7964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barglow KT and Cravatt BF (2007) Activity-based protein profiling for the functional annotation of enzymes. Nat Methods 4, 822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Everley PA, Gartner CA, Haas W, Saghatelian A, Elias JE, Cravatt BF, Zetter BR, and Gygi SP (2007) Assessing enzyme activities using stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 6, 1771–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cravatt BF, Simon GM, and Yates JR (2007) The biological impact of mass-spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 450, 991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li W, Blankman JL, and Cravatt BF (2007) A functional proteomic strategy to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized hydrolases. J Am Chem Soc 129, 9594–9595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saghatelian A, Jessani N, Joseph A, Humphrey M, and Cravatt BF (2004) Activity-based probes for the proteomic profiling of metalloproteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 10000–10005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sieber SA and Cravatt BF (2006) Analytical platforms for activity-based protein profiling–exploiting the versatility of chemistry for functional proteomics. Chem Commun (Camb) 2311–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Evans MJ and Cravatt BF (2006) Mechanism-based profiling of enzyme families. Chem Rev 106, 3279–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sieber SA, Niessen S, Hoover HS, and Cravatt BF (2006) Proteomic profiling of metalloprotease activities with cocktails of active-site probes. Nat Chem Biol 2, 274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, and Rosato A (2006) Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J Proteome Res 5, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, and Rosato A (2006) Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res 5, 3173–3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Weerapana E, Speers AE, and Cravatt BF (2007) Tandem orthogonal proteolysis-activity-based protein profiling (TOP-ABPP)—a general method for mapping sites of probe modification in proteomes. Nat Protoc 2, 1414–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Leeuwenburgh MA, Geurink PP, Klein T, Kauffman HF, van der Marel GA, Bischoff R, and Overkleeft HS (2006) Solid-phase synthesis of succinylhydroxamate peptides: functionalized matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Org Lett 8, 1705–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Freije JR and Bischoff R (2006) The use of affinity sorbents in targeted proteomics. Drug Disc Today: Technol 3, 5–11 doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Horvatovich P, Govorukhina N, and Bischoff R (2006) Biomarker discovery by proteomics: challenges not only for the analytical chemist. Analyst 131, 1193–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sadaghiani AM, Verhelst SH, and Bogyo M (2007) Tagging and detection strategies for activity-based proteomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol 11, 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zucker S and Cao J (2006) Detection of activated, TIMP-free MMPs. Chem Biol 13, 347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hesek D, Toth M, Krchnak V, Fridman R, and Mobashery S (2006) Synthesis of an inhibitor-tethered resin for detection of active matrix metalloproteinases involved in disease. J Org Chem 71, 5848–5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hesek D, Toth M, Meroueh SO, Brown S, Zhao H, Sakr W, Fridman R, and Mobashery S (2006) Design and characterization of a metalloproteinase inhibitor-tethered resin for the detection of active MMPs in biological samples. Chem Biol 13, 379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Toth M, Osenkowski P, Hesek D, Brown S, Meroueh S, Sakr W, Mobashery S, and Fridman R (2005) Cleavage at the stem region releases an active ectodomain of the membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase. Biochem J 387, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Freije JR and Bischoff R (2003) Activity-based enrichment of MMPs using reversible inhibitors as affinity ligands. J Chromatogr 1009, 155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Freije JR, Klein T, Ooms JA, Franke JP, and Bischoff R (2006) Activity-based MMP enrichment using automated, inhibitor affinity extractions. J Proteome Res 5, 1186–1194 doi: 10.1021/pr050483b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Freije R, Klein T, Ooms B, Kauffman HF, and Bischoff R (2008) An integrated HPLC-MS system for the activity-dependent analysis of matrix metalloproteases. J Chromatogr A doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bogyo M (2007) Finding the needles in the haystack: mapping constitutive proteolytic events in vivo. Biochem J 407, e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ikejiri M, Bernardo MM, Bonfil RD, Toth M, Chang M, Fridman R, and Mobashery S (2005) Potent mechanism-based inhibitors for matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem 280, 33992–34002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lee M, Bernardo MM, Meroueh SO, Brown S, Fridman R, and Mobashery S (2005) Synthesis of chiral 2-(4-phenoxyphenylsulfonylmethyl)thiiranes as selective gelatinase inhibitors. Org Lett 7, 4463–4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gu Z, Cui J, Brown S, Fridman R, Mobashery S, Strongin AY, and Lipton SA (2005) A highly specific inhibitor of MMP-9 rescues laminin from proteolysis and neurons from apoptosis in transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 25, 6401–6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kruger A, Arlt MJ, Gerg M, Kopitz C, Bernardo MM, Chang M, Mobashery S, and Fridman R (2005) Antimetastatic activity of a novel mechanism-based gelatinase inhibitor. Cancer Res 65, 3523–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hehr CL, Hocking JC, and McFarlane S (2005) Matrix metalloproteinases are required for retinal ganglion cell axon guidance at select decision points. Development 132, 3371–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ke Z, Lin H, Fan Z, Cai TQ, Kaplan RA, Ma C, Bower KA, Shi X, and Luo J (2006) MMP-2 mediates ethanol-induced invasion of mammary epithelial cells over-expressing ErbB2. Int J Cancer 119, 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Menon B, Singh M, Ross RS, Johnson JN, and Singh K (2006) beta-Adrenergic receptor-stimulated apoptosis in adult cardiac myocytes involves MMP-2-mediated disruption of beta1 integrin signaling and mitochondrial pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290, C254–C261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bonfil RD, Sabbota A, Nabha S, Bernardo MM, Dong Z, Meng H, Yamamoto H, Chinni SR, Lim IT, Chang M, Filetti LC, Mobashery S, Cher ML, and Fridman R (2006) Inhibition of human prostate cancer growth, osteolysis and angiogenesis in a bone metastasis model by a novel mechanism-based selective gelatinase inhibitor. Int J Cancer 118, 2721–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bonfil RD, Dong Z, Trindade Filho JC, Sabbota A, Osenkowski P, Nabha S, Yamamoto H, Chinni SR, Zhao H, Mobashery S, Vessella RL, Fridman R, and Cher ML (2007) Prostate cancer-associated membrane type 1-MMP: a pivotal role in bone response and intraosseous tumor growth. Am J Pathol 170, 2100–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Talamagas AA, Efthimiopoulos S, Tsilibary EC, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, and Tzinia AK (2007) Abeta(1–40)-induced secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 results in sAPPalpha release by association with cell surface APP. Neurobiol Dis 28, 304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sodek KL, Ringuette MJ, and Brown TJ (2007) MT1-MMP is the critical determinant of matrix degradation and invasion by ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer 97, 358–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dive V, Georgiadis D, Matziari M, Makaritis A, Beau F, Cuniasse P, and Yiotakis A (2004) Phosphinic peptides as zinc metalloproteinase inhibitors. Cell Mol Life Sci 61, 2010–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Matziari M, Beau F, Cuniasse P, Dive V, and Yiotakis A (2004) Evaluation of P1′-diversified phosphinic peptides leads to the development of highly selective inhibitors of MMP-11. J Med Chem 47, 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cuniasse P, Devel L, Makaritis A, Beau F, Georgiadis D, Matziari M, Yiotakis A, and Dive V (2005) Future challenges facing the development of specific active-site-directed synthetic inhibitors of MMPs. Biochimie 87, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Devel L, Rogakos V, David A, Makaritis A, Beau F, Cuniasse P, Yiotakis A, and Dive V (2006) Development of selective inhibitors and substrate of MMP-12. J Biol Chem 281, 11152–11160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Matziari M, Dive V, and Yiotakis A (2007) Matrix metalloproteinase 11 (MMP-11; stromelysin-3) and synthetic inhibitors. Med Res Rev 27, 528–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.David A, Steer D, Bregant S, Devel L, Makaritis A, Beau F, Yiotakis A, and Dive V (2007) Cross-linking yield variation of a potent matrix metalloproteinase photoaffinity probe and consequences for functional proteomics. Angew Chem Int Ed 46, 3275–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]