Abstract

AbstractThis study evaluated the effect of early weaning (EW) of artificially reared lambs using a restricted milk replacer (MR) feeding and step-down weaning system on the short- and long-term effects on growth, feed intake, selected blood metabolites and hormones, body composition, and small intestine development. Mixed-sex twin-born 2 to 5 d old lambs were randomly allocated to individual pens and fed MR at 20% of initial individual BW in week 1 and 15% in week 2 followed by weaning off MR by the end of week 4 (EW; n = 16) or week 6 (Control; Ctrl, n = 16) using a step-down procedure. Concentrate starter and fiber diets were offered ad libitum to week 9, then gradually removed over a 10-d period. All lambs were managed as a single group on pasture from weeks 6 to 16 of the trial. Feed intake was recorded daily in the first 6 wk, and BWs recorded weekly. At weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, and pre- and postclostridial vaccination at week 8, blood samples were collected for analysis of selected blood metabolites, IGF-1, and immune function. Body composition was evaluated in eight animals per group at weeks 4 and 16 after euthanasia, and duodenal samples collected for histomorphometric evaluation. Early weaned lambs had lower DM, ME, CP, and NDF intake than Ctrl lambs at 21, 15, 21, and 36 d of rearing, respectively (P < 0.001), driven by lower intakes of MR from day 15 (P < 0.001) as per the experimental design, and lower total DMI of fiber (P = 0.001) from 21 to 42 d of rearing. Lamb BW tended (P = 0.097) to be lower in EW than Ctrl lambs from 5 to 10 wk of rearing, with lower ADG in EW lambs from weeks 3 to 6 (P = 0.041). Early weaning had negligible effects on duodenal morphology, organ, and carcass weights at weeks 4 and 16. Plasma metabolites (urea nitrogen, triglycerides, NEFA, glucose, and total protein) were similar between groups, while β-hydroxybutyrate was greater in EW than Ctrl lambs at weeks 4 and 6 (P = 0.018) but not week 8 indicative of early rumen development. Serum IGF-1 tended to be lower in EW than Ctrl lambs from weeks 2 to 6 only (P = 0.065). All lambs developed antibody responses postvaccination and there was no effect of treatment (P = 0.528). The results of this study illustrate that artificially reared lambs can be weaned off MR by 4 or 6 wk of rearing without compromising growth, small intestine morphology, major organ development, and body composition, nor immune function at either 4 (preweaning) or 16 (postweaning) wk of age.

Keywords: growth, metabolism, nutrition, sheep, small intestine

Introduction

Optimizing lamb survival and growth of artificially reared lambs in dairy sheep systems is important to generate quality ewe replacements and to increase the amount of ewe milk available for processing (David et al., 2014). Artificial rearing is also important for utilization of surplus lambs from dairy sheep systems, and lambs from meat sheep operations that are not able to be naturally reared (e.g., orphans) to generate additional revenue from meat production as well as meeting market- and public-driven expectations on animal welfare. A variety of rearing options are employed worldwide (McKusick et al., 2001; Bimczok et al., 2005). Reducing rearing costs are a key contributor to profitability, therefore, rearing systems that reduce feed and labor inputs without compromising the growth, health, and well-being of the lambs are desirable.

Gastrointestinal conditions can adversely affect health, welfare, and growth performance of animals and increase susceptibility to disease. At birth, the rumen is a nonfunctional compartment of the digestive tract (Baldwin, 2000) and lambs function as a monogastric (Longenbach and Heinrichs, 1998). The small intestine therefore plays a key role in driving nutrient metabolism, immunological competence, neonatal survival, and postnatal growth (Meyer and Caton, 2016). Feeding systems in the first few weeks of life can influence the development of the small intestine (Górka et al., 2011). Early weaning systems are routinely used in swine production systems to reduce cost but can have negative effects on small intestine development and function (Pluske et al., 1997; van Beers-Schreurs et al., 1998). Growth checks can occur if weaned lambs consume low amounts of solid feed at weaning (Lane et al., 1986), which has driven the development of restricted milk feeding methods to encourage early intake of starter diets to support rumen development and growth (Bimczok et al., 2005). We have recently reported that the morphological and physiological development of the rumen can be accelerated to support weaning of artificially reared lambs at 4 wk, using a step-down weaning system (Cristobal-Carballo et al., 2019). While early weaning of lambs has the potential to reduce the cost of artificial lamb rearing systems, the implications on the physiological development of the lamb is poorly understood.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of early weaning on growth, feed intake, metabolic, and endocrine development during the rearing phase, and on small intestine morphology, growth rate, and body composition at 4 and 16 wk of age. We hypothesize that early restriction of milk intake through a step-down weaning procedure will reduce growth rate of early-weaned lambs preweaning as a result of restricted milk intake, but there will be no long-term negative effects on growth, body composition, metabolic, or endocrine function to 16 wk of age.

Materials and Methods

Animal manipulations in this study including welfare, husbandry, and experimental sampling were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of AgResearch Grasslands, Palmerston North, New Zealand, in compliance with the institutional Code of Ethical Conduct for the Use of Animals in Research Testing and Teaching, as prescribed in the Animal Welfare Act of 1999 and its amendments (New Zealand).

The experimental design and feeding regime for this study have been described elsewhere (Cristobal-Carballo et al., 2019). Briefly, 32 mixed sex twin-born lambs born to Romney crossbred ewes (one twin per ewe) were sourced from a commercial farm. Lambs were separated from their dams on the same day at 3 to 5 d of age to enable sufficient colostrum intake from their dams. The lambs were randomly allocated to one of two groups based on BW and sex for weaning off milk at either 4 wk (early weaning; EW) or 6 wk (Control; Ctrl) after the start of artificial rearing. The lambs were housed indoors in a temperature-controlled facility (18 °C) in 1.2 m2 individual pens with opening on all four sides to allow visual and physical interactions with neighboring lambs. Kiln dried wood shavings were used as bedding. General animal health (e.g., incidence of scouring, respiratory issues, and nasal discharge) were monitored daily. One lamb was treated for conjunctivitis in week 1. Two lambs were treated with antibiotics for navel infection in the first week of the trial (one EW and one Ctrl). All animals remained in the trial.

Feeding Management, Intake, and Feed Composition

From arrival, lambs were individually fed reconstituted casein-based milk replacer (MR; AnLamb, NZAgbiz Auckland, NZ; Table 1) at a volume equivalent to 20% of initial BW (40 g of DM/kg of BW mixed at 200g/L and offered at a temperature of ~37 ºC). In week 1, all lambs were offered MR in four equal rations at 0800, 1200, 1600, and 2000 hours. In week 2, all lambs were fed three times daily (0800, 1200, and 1600 hours) the same volume of milk offered in week 1 (i.e., one feed was removed and total milk volume offered reduced by 25%). Lambs in the EW group were step-down weaned over 2 wk by further reducing the milk volume by 25% (i.e., removing 1 feed/wk) with complete milk removal at the end of week 4. Step-down weaning of the Ctrl group mirrored that of the EW group during weeks 5 and 6 with complete milk removal at the end of week 6. Fresh water was available ad libitum throughout the study. Lambs were offered ad libitum grain-based starter diet and chopped meadow hay individually from the start of the trial, and daily feed intake recorded as the difference between refused and offered feed. Composition of the diets is described by Cristobal-Carballo et al. (2019). At week 6, both groups were transitioned outdoors onto a mixed ryegrass and white clover pasture sward and gradually weaned off supplementary concentrate and chopped meadow hay over 10 d from week 9.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (% of DM) of the milk replacer (MR), starter, and fiber fed to lambs during the first 6 wk of rearing, and of the mixed ryegrass and white clover pasture grazed during the postweaning rearing

| MR | Starter | Fiber | Pasture10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM1 | 94.9 | 88.9 | 88.2 | 12.7 |

| CP2 | 24.0 | 20.1 | 11.1 | 31.7 |

| ADF3 | — | 6.4 | 35.9 | 18.1 |

| NDF4 | — | 15.7 | 55.2 | 40.5 |

| Organic matter5 | 94.5 | 88.9 | 91.0 | 87.0 |

| Soluble sugars6 | 40.5 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 7.3 |

| Starch7 | — | 35.6 | — | — |

| Ether extract8 | 25.0 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 5.7 |

| Ash9 | 5.5 | 11.1 | 9.1 | 10.9 |

1DM, dry matter; Method 945.15; AOAC (2010).

2CP, crude protein; Method 992.15; AOAC (2010).

3ADF, acid detergent fiber; Method 7.074; AOAC (1990).

4NDF, neutral detergent fiber; Method 7.074; AOAC (1990).

5Method 942.05; AOAC (2010).

6Paul, A.A and Southgate, D.A. The Composition of Foods. 4th Edition, 1978.

7Method 996.11; AOAC (2010).

8Total Fat* Subcontracted test, Cawthron Institute, Nelson.

9Method 942.05; AOAC (2012).

10The chemical composition analyzed by near infrared reflectance spectroscopy in accordance with the methods of Corson et al. (1999).

Blood Sampling and Analysis

Jugular venipuncture blood samples were collected on arrival for evaluation of γ glutamyltransferase (GGT) as an indicator of colostral transfer (Maden et al., 2003). Lambs were fed in pairs at 2 min intervals to enable timed collection of jugular venipuncture blood samples 2 h postfeeding at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 wk of the trial using 10 mL potassium-EDTA containing vacutainers (Becton Dickinson Ltd., Auckland, NZ) put on ice for 40 to 60 min and then centrifuged for 15 min at 1,000 × g, and plasma stored at −20 °C until analysis. Analysis of GGT (day 0 only) was undertaken by the New Zealand Veterinary Pathology Laboratory (Palmerston North, NZ). Blood metabolites were analyzed using the Roche modular platform P800 module using Randox kits (Randox Laboratories Ltd, UK) and the following methods: glucose using the hexokinase method (Enzymatic UV test), triglycerides using an enzymatic color test, NEFA and β-hydroxybutyrate (BOH) using a colorimetric measurement ACS-ACOD-MEHA (including Maleimide) method, total protein using the Biuret method and blood urea nitrogen using a kinetic UV test. Serum IGF-1 was analyzed using enzyme labeled chemiluminescent immunometric assay run on an Immulite 1000 analyzer (Siemens Healthcare, Victoria, Australia). These kits had lower limits of detection of 0.729 mmol/L, 0.26 mmol/L, 0.072 mmol/L, 0.100 mmol/L, 4.76 g/L, and 2.13 mmol/L, respectively, and duplicate reactions had CVs of <5%.

All lambs were vaccinated with Ultravac five in one clostridial vaccine (Zoetis, Auckland, NZ) at 8 wk of the experiment. Blood samples were collected 10 d postvaccination via jugular venipuncture using heparinized vacutainers (Becton Dickinson Ltd), plasma harvested and stored at −80 °C. Antibody responses in plasma were determined by ELISA with all steps being performed at room temperature unless indicated otherwise. 96-well Maxisorb plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with aliquots of the anti-clostridial vaccine diluted 1:100 in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) by incubation for 2 h and followed by 4 °C overnight. After five washes with PBS the plates were blocked with 150 μL/well PBS Tween 20 (PBST) containing 1% (w/v) casein and merthiolate (1:10,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min. Blocking buffer was removed and 100 μL/well of plasma samples were added. Dilution series of plasma samples from 1:100 to 1:3,200 in PBST containing casein and merthiolate were used and plates were incubated for 2 h. After five washes with PBS, 100 µL/well of conjugated anti-bovine IgG horse radish peroxidase (1:6000, AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) were added and the plates incubated for 1 h. After five washes with PBS, 100 μL/well of 3.3′,5.5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were added and the plates incubated for 10 min. Reactions were read at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader (VERSAmax microplate reader; Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Antibody levels were expressed as “titers,” which were defined as the highest dilution at which the OD reading was greater from the postvaccination sample compared with the prevaccination sample.

BW, Body Composition, and Duodenal Morphology

The BW of individual animals was recorded on arrival and weekly throughout the trial to monitor growth and to calculate pre- and postweaning ADG. At weeks 4 and 16, eight animals per group were randomly selected and euthanized by captive bolt stunning and exsanguination. The visceral organs (liver, kidneys, perirenal fat, spleen, lungs, heart, and adrenals), thyroid, and thymus were dissected free of connective tissue and weighed, and the gastrointestinal tract (rumen, abomasum, small, and large intestine) emptied and the weights recorded. The pelt, head, and legs were removed and carcass weight recorded. Longissimus dorsi eye muscle depth and width and fat depth at the GR (mid-point of the eye muscle) and C (10 cm from the spine) site between the 12th and 13th ribs were measured manually and recorded. Tissue samples were collected from the duodenum (10 cm posterior to the pylorus). The tissue samples were immediately flushed with ice-cold saline to remove luminal contents and fixed in 10% buffered paraformaldehyde for later histological analysis of intestinal morphology. Histology sections were prepared by a commercial Histopathology Laboratory (Massey University, Palmerston North, NZ). For each animal, two sections were trimmed from each sample via a transverse cut through the villi and dehydrated overnight through graded alcohols (70%, 95%, and absolute alcohol) at ambient temperature. Xylene was used to remove the alcohol, and the samples were impregnated with Histosec paraffin pastilles (Merck Ltd., Auckland, NZ) under pressure at 60 °C in a tissue processor (Excelsior ES, ThermoFisher, Albany, NZ). Treated tissues were embedded (HistoStar, ThermoFisher, Albany, NZ) and cut with a rotary microtome (microTec, Walldorf, Germany). The 4 µm thick sections were stained using the hematoxylin-eosin method by means of an autostainer (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Villus height and width, crypt depth, villus height and crypt depth ratio, goblet cell number, villus density, muscle layer, and epithelium thickness were evaluated as measures of tissue morphological development. The height and width of 20 villi were measured, with their corresponding number of goblet cells as well as the depth of 20 crypts using a light microscope (BH2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) coupled with a digital camera (ProgRes C14, Jenoptik, Jena, Germany) to a computer and image processing software (Image-Pro 7.0, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). The muscularis propria thickness was measured in 20 separate areas on each slide. Goblet cells were distinguished from the epithelial cells based on visible droplets of mucus within each cell. The number of villi measured was based on a review of current literature which indicated 20 villi was sufficient to provide an accurate average. A single operator was used for all measurements and the treatment regimens remained anonymous. The height of the villus was measured from its basal region, which coincides with the top of the crypt, to the apex of the villus. The width of the villus was measured at its basal region. The depth of the crypt was measured from its base to the crypt-villus transition (Caruso et al., 2012). A villus was considered adequate when its base was clearly embedded in the submucosa, simple columnar epithelium was present at the tip and the body did not present any discontinuity (Gava et al., 2015).

Statistical Analysis

All lambs surviving to weaning were used in the analysis of preweaning variables, and all lambs surviving to the end of the trial were included in the analysis of postweaning variables. Single time points and repeated measurement data were analyzed using the Residual Maximum Likelihood algorithm in linear models and linear mixed effect models using Genstat (GenStat release 17.1, VSN International, Oxford, UK). When analyzing body composition and organ weight data, the model included the fixed effects of sex and treatment group with carcass weight as a covariate. For GGT, the model consisted of the fixed effects of sex and treatment group. For IGF-1 and plasma metabolites, a repeated measures model was fitted using a first-order autoregressive error with fixed effects of sex, treatment and time (d), and their first-order interactions. For BOH, the assay detection limit was 0.1 and any values recorded as ≤0.1 were replaced with random values between 0 and 0.1 before being subject to the aforementioned repeated measures model. Repeated measures for live weight were evaluated as described for IGF-1 and plasma metabolites with the exception that the predicted means of treatment effects on BW during the first 4 wk and last 13 wk were compared using a t-test. ADG and immune function data were analyzed using ANOVA with treatment group fitted as the main factor using individual animals as replicates. Daily intakes of concentrate and fiber were analyzed using repeated measures fitting the data using a first-order autoregressive error with fixed effect of sex, treatment and time (d), and their first-order interactions. Overall effects of treatment on solid feed and nutrient intake were evaluated using REML with the fixed effects of sex and treatment group, while BW at day 0 was used as a covariate. Data of villi height and width, crypt depth, muscularis propria thickness, and villus height:crypt depth ratio were subjected to an REML variance components analysis using the statistical program R (R Core team, 2016). Data of goblet cell number were subjected to a generalized linear mixed model analysis. Both statistical models applied treatment as the fixed effect and individual animals as the random effect. The significance of treatment effects is indicated as follows: ns P > 0.10; † P < 0.10; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Data are presented as predicted means ± SEM.

Results

Animal Health

Mortality preweaning was 3%, with one Ctrl lamb euthanized that had poor appetite on entry into the rearing facility and failure to respond to antibiotics following a navel infection. Postweaning mortality was also 3%, with one sudden death of a Ctrl lamb in week 11. Postmortem diagnosis was chronic copper toxicity. No digestive or respiratory issues were recorded.

Feed DMI

Total daily DMI of all feeds (MR, starter, and fiber) increased during the rearing period (P < 0.001) in both groups. A treatment by time interaction was evident (P < 0.001) with lower intake of DM, ME, CP, and NDF in EW compared with Ctrl lambs from 21, 15, 21, and 36 d of rearing, respectively (Fig. 1A–D). The lower total daily intakes in EW compared with Ctrl lambs were driven by lower intakes of MR from 15 d of rearing (P < 0.001; Fig. 2A) as per the experimental design, and total DMI of fiber which was lower in EW compared with Ctrl lambs (P = 0.001) from 21 to 42 d of rearing (Fig. 2B). Total daily fiber DMI before 21 d of rearing was negligible (<6 g/d) and tended to increase over time particularly in the Ctrl group (P = 0.056) but a treatment by time interaction was not evident (P = 0.118). Starter concentrate DMI before 21 d of age was negligible (<50 g/hd/d), and steadily increased from 21 to 42 d of rearing in both groups (P < 0.008) reaching ~650 g/hd/d in both groups by 42 d, but there was no effect of treatment (P = 0.410) nor a treatment by time interaction (P = 0.438; Fig. 2C).

Figure 1.

Total daily DMI (A), ME (B), CP (C), and NDF (D) of all feeds (milk replacer, starter, and fiber) in the first 6 wk of artificial rearing in lambs weaned at 4 (EW) compared with 6 (Ctrl) wk of rearing. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Total daily DMI of milk replacer in the first 42 d of rearing (milk replacer, MR; A) and total starter concentrate (B) and fiber (C) from 21 to 42 d of artificial rearing in lambs weaned at 4 (EW) compared with 6 (Ctrl) wk of rearing. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

In the first 6 wk of rearing total cumulative DMI of MR was lower in EW than Ctrl lambs (4.0 ± 0.14 vs. 6.0 ± 0.14 kg, P < 0.001) with corresponding lower CP (0.96 ± 0.033 vs. 1.45 ± 0.033 kg, P < 0.001) and fat (1.00 ± 0.034 vs. 1.51 ± 0.035 kg, P < 0.001) intakes. Total concentrate DMI in the first 6 wk of rearing was similar in EW and Ctrl lambs (9.4 ± 0.75 vs. 8.1 ± 0.75 kg, P = 0.299) with corresponding similar CP (1.89 ± 0.015 vs. 1.64 ± 0.015 kg, P = 0.299) and fat (0.25 ± 0.020 vs. 0.22 ± 0.020 kg, P = 0.299) intakes. Total fiber DMI in the first 6 wk of rearing was lower in EW compared with Ctrl lambs (0.48 ± 0.182 vs. 1.12 ± 0.182 kg, P < 0.026) with a tendency for a lower total CP intake (0.11 ± 0.032 vs. 0.19 ± 0.032 kg, P = 0.104).

BW, ADG, and Skeletal Growth

There was a tendency for a treatment by time interaction for BW (P = 0.097) whereby a divergence was observed from 5 to 10 wk of rearing only (Fig. 3). There was an effect of treatment (P = 0.041) on weekly ADG with lower ADG apparent in EW lambs during weeks 3 to 6 only (Fig. 4). Weekly ADG differed with time (P < 0.001) with high variation in ADG observed during the rearing period primarily associated with changes in diet, i.e., MR and starter diet weaning transitions (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

BW for the first 16 wk of life in lambs weaned at either 4 (EW) or 6 wk (Ctrl) of rearing. Data presented are predicted means ± SEM.

Figure 4.

ADG for the first 16 wk of life in lambs weaned at either 4 (EW) or 6 wk (Ctrl) of rearing. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Small Intestine Morphology

At 4 wk, duodenal villi width was 17% greater in EW compared with Ctrl lambs (P = 0.03), but there were no differences in villus height, crypt depth, muscularis propria thickness, goblet cell number, or villus height:crypt depth ratio (Table 2). Similarly, no differences in duodenal morphology were evident between the groups at 16 wk of age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Duodenal histomorphological parameters early weaned (EW) or control (Ctrl) lambs after 4 or 16 wk of rearing1

| Parameter | EW | Ctrl | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 wk | ||||

| Villi height, µm | 348 | 369 | 19.7 | 0.473 |

| Villi width, µm | 131 | 153 | 6.1 | 0.031 |

| Crypt depth, µm | 355 | 370 | 25.2 | 0.679 |

| Muscularis propria thickness, µm | 287 | 330 | 39.8 | 0.460 |

| Villus height:crypt depth ratio | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.985 |

| Goblet cell number | 3.00 | 3.21 | 0.25 | 0.895 |

| 16 wk | ||||

| Villi height, µm | 323 | 337 | 50.9 | 0.843 |

| Villi width, µm | 140 | 138 | 10.8 | 0.895 |

| Crypt depth, µm | 587 | 494 | 66.4 | 0.341 |

| Muscularis propria thickness, µm | 356 | 295 | 30.1 | 0.175 |

| Villus height:crypt depth ratio | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.883 |

| Goblet cell number | 1.04 | 1.09 | 0.25 | 0.765 |

1Data presented are predicted means and SEM.

Organ Development and Carcass Traits

BW, carcass weight, and major organ weights of the lambs at week 4 of the trial are presented in Table 3. There was a tendency (P = 0.062) for EW lambs to have a lower LW than Ctrl lambs at 4 wk of the trial. The weight of the large intestine was lower (P = 0.024), and there was a tendency for the thymus weight (P = 0.053) and large intestine length (P = 0.086) to be lower in EW compared with Ctrl lambs at 4 wk. There was no evidence of a treatment difference in carcass weight nor individual organ or muscle weights at 4 wk. BW, carcass weight, carcass fatness, and weight of selected muscles and organs did not differ between EW and Ctrl lambs at 16 wk of the trial (Table 4).

Table 3.

The BW and organ weights of early weaned (EW) or control (Ctrl) lambs after 4 wk of rearing1

| Parameter | EW | Ctrl | SED | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW, kg | 10.4 | 11.5 | 0.549 | 0.062 |

| Carcass, kg | 5.09 | 5.50 | 0.357 | 0.280 |

| Liver, g | 175.5 | 184.4 | 14.28 | 0.178 |

| Kidneys, g | 47.1 | 49.1 | 3.85 | 0.600 |

| Perirenal fat, g | 46.3 | 55.2 | 11.03 | 0.401 |

| Spleen, g | 20.2 | 21.6 | 2.62 | 0.604 |

| Lungs, g | 199.1 | 184.3 | 42.98 | 0.739 |

| Heart, g | 72.4 | 72.5 | 4.55 | 0.992 |

| Thyroids, g | 2.31 | 1.97 | 0.301 | 0.293 |

| Adrenals, g | 1.25 | 1.26 | 0.100 | 0.478 |

| Thymus, g | 64.9 | 88.6 | 10.97 | 0.053 |

| Small intestine, g | 250.7 | 287.6 | 38.44 | 0.358 |

| Abomasum, g | 489.4 | 541.4 | 83.67 | 0.548 |

| Large intestine, g | 68.0 | 87.3 | 7.41 | 0.024 |

| Semitendinosus, g | 31.0 | 35.3 | 2.49 | 0.119 |

| Rumen full, g | 994.8 | 807.5 | 133.1 | 0.187 |

| Rumen empty, g | 135.0 | 125.4 | 14.08 | 0.448 |

1Data presented are predicted means and SED and P-values.

Table 4.

The BW, carcass traits, selected muscle, and organ weights of early weaned (EW) or control lambs at 16 wk of rearing1

| Parameter | EW | Ctrl | SED | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW, kg | 39.1 | 40.3 | 1.45 | 0.413 |

| Carcass, kg | 17.7 | 18.3 | 0.71 | 0.400 |

| Fat GR, mm | 5.1 | 7.5 | 1.95 | 0.251 |

| Fat C, mm | 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.620 | 0.188 |

| EMW, mm | 62.7 | 60.2 | 1.59 | 0.154 |

| EMD, mm | 29.1 | 28.3 | 1.32 | 0.579 |

| Liver, g | 825.2 | 810.9 | 41.13 | 0.733 |

| Small intestine, g | 1132 | 1098 | 71.32 | 0.664 |

| Semitendinosus, g | 102.5 | 116.4 | 13.41 | 0.356 |

| LD, g2 | 582.1 | 539.9 | 47.09 | 0.391 |

| Tenderloin, g | 94.9 | 85.8 | 5.83 | 0.146 |

| Rumen full, g | 5162 | 4808 | 260.5 | 0.201 |

| Rumen empty, g | 826.5 | 814.7 | 28.19 | 0.683 |

1Data presented are predicted means, SED, and P-values.

2 Longissimus dorsi (LD) eye muscle depth (EMD) and width (EMW) and fat depth at the GR (mid-point of the eye muscle) and C (10 cm from the spine) site between the 12th/13th ribs.

Blood Metabolites and IGF-1

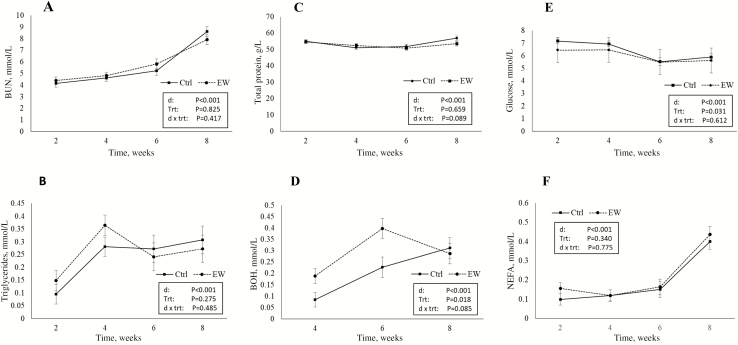

Plasma metabolite profiles are presented in Fig. 5. Blood urea nitrogen increased with time (P < 0.001), but there was no evidence of a treatment (P = 0.825) or treatment by time interaction (P = 0.417). Triglycerides increased with time (P < 0.001) with no evidence of a treatment (P = 0.275) or treatment by time interaction (P = 0.485). There was a tendency (P = 0.089) for a treatment by time interaction for total protein, where EW lambs had lower concentrations of total protein at 8 wk of the trial. Blood glucose levels decreased over time (P < 0.001), and there was an effect of rearing diet on glucose levels (P = 0.031) whereby EW lambs had lower levels of glucose at week 2 of the trial only, but there was no evidence of a treatment by time interaction (P = 0.612). There was a trend for a treatment by time interaction for BOH (P = 0.085) whereby EW lambs had greater levels of BOH at 4 and 6 wk (P = 0.018) compared with Ctrl lambs with no differences evident between groups at week 8. Levels of BOH at week 2 were below detection limits in both groups. The levels of NEFA increased with time (P < 0.01) but did not differ between treatment groups (P = 0.340) and there was no evidence of a treatment by time interaction (P = 0.775).

Figure 5.

Plasma concentrations of blood urea nitrogen (BUN; A), triglycerides (B), total protein (C), β-hydroxybutyrate (BOH; D), glucose (E), and NEFA (F) from 2 to 8 wk of rearing in artificially reared lambs weaned at 4 (EW) or 6 wk (Ctrl) of rearing. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

There was a trend for a treatment by time interaction (P = 0.065) for serum concentrations of IGF-1 whereby EW lambs had lower levels of IGF-1 compared with Ctrl lambs from 2 to 6 wk of the trial, but no difference was evident between treatment groups by week 8 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Serum IGF-1 profiles from 2 to 8 wk of rearing in artificially reared lambs weaned at 4 (EW) or 6 wk (Ctrl) of rearing. Data presented are predicted means and average SED.

Immune Function

All lambs had adequate levels of GGT upon entry to the trial and there were no differences evident between the EW and Ctrl lambs (400.9 vs. 429.0 IU/L, SED 108.2, P = 0.797). Low levels of anti-clostridial IgG in prevaccination serum was detected in both groups. Both EW and Ctrl lambs developed an antibody response postvaccination but there was no effect of treatment on either the relative increase in anti-clostridium IgG from pre- to postvaccination (Fig. 7; P = 0.528), or in the antibody titer (400 vs. 875, SED = 386, P = 0.239).

Figure 7.

Anti-clostridial immunoglobulin levels after vaccination with Ultravac five in one clostridial vaccine at 8 wk in artificially reared lambs weaned at 4 (EW) or 6 (Ctrl) wk of rearing. Antibody levels are expressed as “titres,” defined as the highest dilution at which the OD reading was greater from the postvaccination sample compared with the prevaccination sample. Data are presented as the mean (crosses) as well as individual data points (bullets).

Discussion

The results of this study illustrate that lambs separated from their dams at 3 to 5 d of age and artificially reared on a restricted milk intake diet with ad libitum access to forage and concentrate starter diets can be successfully weaned at 4 (EW) compared with 6 wk of rearing using a step-down weaning procedure without influencing growth performance to 16 wk of age. Further, while early weaning was associated with increased rumen metabolic function, there was no effect of early weaning on small intestine development, metabolic, immune and endocrine function, or body composition. Collectively, these results illustrate that early weaning can be employed as a strategy to reduce feed costs associated with rearing lambs artificially.

A high incidence of animal health issues and mortality is often characteristic of artificial lamb rearing systems. Previous studies have noted elevated incidence of diarrhea episodes from weeks 2 to 5 in artificially reared lambs (Belanche et al., 2018) and associated increased antibiotic use. In the present study, there was nil incidence of diarrhea, and antibiotics were only used in two lambs for navel infections (6%), which is a sign of a good management system (Berger and Schlapper 1993). Overall lamb mortality in this study was 6% (two lambs), which in general is considered a good result (Lindahl et al., 1972; Lane et al., 1986). It is unclear whether death of the Ctrl lamb from copper toxicity was due to ingestion of high amounts of concentrate as individual intakes were not able to be recorded postweaning when outdoors. Copper poisoning has been recorded when concentrate intake is high (Suttle et al., 1996). Other potential causes of copper poisoning, such as interactions with copper, molybdenum and sulfate, and diet-induced hepatotoxicity (Underwood and Suttle 1999), are unlikely. A subset of other lambs in the study was profiled for serum copper, and all were within normal limits.

Meeting energy and protein requirements of young ruminants are critical to support growth (Brown et al., 2005). However, restricted feeding of MR and/or early weaning are commonly employed to reduce the cost of artificial rearing of lambs (Lane et al., 1986). Solid feed is routinely provided at an early age to increase nutrient intake and growth rate (Poe et al., 1969; Bhatt et al., 2009) and to promote rumen development to support weaning off MR (Baldwin et al., 2004; Khan et al., 2016). Intakes of solid feed in lambs before 3 wk of age are low (Owen et al., 1969; Lane et al., 2000; Geenty 2010). Consistent with these observations, in the present study, DM and nutrient intake (ME and CP) from solid feeds was highly variable between animals (0 to 250 g/hd/d) in the first 3 wk of rearing (data not shown) with average intakes for both treatment groups of <50 g/hd/d. Solid feed intake (starter and fiber) increased in both groups from 21 to 42 d of rearing despite the differential MR intake and ranged from 430 to 1,280 g/hd/d. Interestingly, however, fiber intake was also lower in EW than Ctrl lambs during the same period and ranged from 20 to 226 g/hd/d in Ctrl lambs and 0 to 59 g/hd/d in EW lambs. These results were unexpected due to the previously reported association between decreased milk volume and increased solid feed intake (Penning and Treacher 1975). This difference may be due to the restricted milk intake in both groups in the present study stimulating solid feed intake.

While total dietary DM, ME, and CP intake were lower in EW than Ctrl lambs, plasma metabolite levels (total protein, triglycerides, glucose, urea, and NEFAs) were similar during rearing for both groups. The fermentation capacity of the rumen was similar in both groups (Cristobal-Carballo et al., 2019); therefore, these results indicate that physiological development of the rumen wall to absorb nutrients may have been affected, as indicated by increased plasma BOH in EW than Ctrl lambs at both 4 and 6 wk. We speculate that increased capacity to absorb and utilize nutrients from solid feed may have been able to compensate for the lower total nutrient intake and thus to maintain homeostasis of blood metabolites relative to Ctrl lambs. These observations are consistent with the observations of Belanche et al. (2018) where similar plasma metabolite profiles were observed in naturally and ad libitum milk-fed artificially reared lambs. However, in contrast to the observations of Belanche et al. (2018) where naturally reared lambs compensated for lower milk intake in the latter rearing period by increasing the intake of solid feed, in our study, no effects on concentrate intake and lower intake of fiber in EW than Ctrl lambs was evident likely due to the restricted milk intake in both groups.

Despite plasma metabolite homeostasis, EW lambs grew slower than Ctrl lambs from weeks 3 to 6 concomitant with the earlier reduction in MR allowance as part of the step-down weaning process. The observed reduction in growth rate in EW compared with Ctrl lambs during this period was associated with a reduction in plasma glucose at week 2, and a sustained reduction in serum IGF-1 from 2 to 6 weeks concomitant with the lower milk consumption during this period. Circulating IGF-1 is a potent growth factor driven by improved nutrient supply (Hammon and Blum, 1997; Rhoads et al., 2000; Greenwood et al., 2002) with elevated levels of IGF-1 in growing animals associated with faster growth (Breier et al., 1986).

Slower growth rate in early life can influence the amount of time it takes an animal to reach target weights for sale, slaughter, or breeding (Litherland and Lambert, 2000). However, in this study, the lower growth rate of EW than Ctrl lambs was short term in nature with no effect on body composition and organ development at 4 wk nor body composition and carcass traits, including subcutaneous fat deposition, at 16 wk. In this study, lambs reached ~38 kg BW (range of 36 to 50 kg) by 16 wk of age irrespective of the age of weaning illustrating no carryover negative effect of restricted MR intake and early weaning on overall body growth. The absence of a long-term impact of mild growth restriction in early life in this study is consistent with the observations of Bimczok et al. (2005). However, recent research indicates potential adverse effects of early milk restriction on systemic (not rumen) metabolic disorders during the fattening phase related to lipid metabolism and adiposity (Frutos et al., 2018a). Furthermore, negative effects of early milk restriction on feed efficiency during the fattening phase have also been described in Merino lambs which may be related to altered liver function (Santos et al., 2018a) potentially via modulation of fatty acid metabolism, protein catabolism, and detoxification of xenobiotics (Santos et al., 2018b). While no adverse health effects were observed in the present study, and fat deposition in the carcass was similar, the impact of early MR restriction on metabolic function, feed efficiency, and health in lambs destined for milking flocks or breeding programs warrant further investigation.

Importantly, despite the reduction in growth rate in EW lambs, a reduction in growth rate often observed with weaning of young lambs (Lane et al., 1986) was not observed in either group in this study highlighting the value of the step-down weaning process in supporting the transition from milk to solid feed. In fact, growth rates in both EW and Ctrl lambs increased during week 5 which was associated with the increase in intake of the concentrate and fiber diets, with the substantial increase in ADG likely due at least in part to gut fill. The lack of difference in plasma NEFA and triglycerides also indicates that there was no effect of milk removal in either group on energy balance. This is likely due to the restricted milk feeding regime employed in this study which promoted early solid feed intake which reduces the impact of milk weaning on growth when starter intakes are low (Lane et al., 1986) coupled with the gradual removal of MR (Heaney et al., 1984; McKusick et al., 2001). Consistent with this notion, no differences in rumen morphological development or fermentation capacity was observed between groups (Cristobal-Carballo et al., 2019).

In contrast to milk weaning, removal of the fiber and concentrate diets during weeks 9 and 10 (10 d transition period) was associated with a substantial reduction in ADG in both groups in the week after removal of these diets. These results indicate that despite having ad libitum pasture available from 6 wk, a 10 d weaning transition was insufficient to avoid a reduction in growth rate in both groups and that a longer transition may be required to reduce the severity of the growth restriction. However, growth rates recovered by week 12 and remained high (>400 g/d) in both groups until the end of the trial indicating that both groups had similar ability to utilize a pasture-only diet to maintain high levels of growth.

Changes in the structure of the villi determine the digestive and absorptive capacity of the small intestine (Tivey and Smith, 1989). Notably, villus height and crypt depth are important for nutrient absorption (Mir et al., 1987) and villus height and width, depth of the depth of the crypts and number of goblet cells are indicators of intestinal integrity (Vente-Spreeuwenberg and Beynen, 2003). No adverse effects of early weaning on small intestine morphological development or markers of intestinal integrity were observed in this study at both 4 and 16 wk, which is consistent with the lack of a weaning growth check and subsequently no difference in growth rate. These results are consistent with the observations of Shirazi-Beechey et al. (1991) who reported that removal of lambs from their dams within 72 h postpartum and artificially rearing with MR using a restricted allowance system did not diversely affect intestinal structure compared with naturally reared lambs when compared at 35 d of age. These results indicate that the milk feeding regimes employed in the current study were sufficient to support small intestine development and function to support growth in young lambs.

Similar small intestine morphology at 4 and 16 wk in the present study indicates that substantial development of the intestinal villi occurs in the first 4 to 5 wk of age in the lamb. However, the villus height:crypt depth ratio and goblet cell numbers were greater at week 4 compared with week 16 irrespective of treatment group. New intestinal cells migrate from the base of the crypt along the epithelial surface to the top of the villus and increased villus height:crypt depth ratio is an indicator of enhanced intestinal cell proliferation and/or reduced cell apoptosis (Tan et al., 2010). Therefore, the greater villus height:crypt depth ratio observed at 4 compared with 16 wk highlights the greater rates of intestinal cell proliferation and/or apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium which is expected during early stages of development. Goblet cells are mucin-secreting cells in the intestinal epithelium that creates a physical barrier at the mucosal surface with a key role in innate host defense (Kim and Ho, 2010). Greater goblet cell numbers per villus at 4 compared with 16 wk observed in the present study likely indicates that the intestinal epithelium is more highly primed to protect against pathogens in the first few weeks of life.

Colostrum intake, milk feeding and weaning, and management are critical influences on the development of the immune system in newborn ruminants in the first few months of life (Hernandez-Castellano, 2015). Weaning is one of the most critical phases in domestic ruminant production due to the impact of changes in feeding strategies on stress, which can increase disease susceptibility and attenuation of the immune system (Hickey, 2003). The timing of early weaning influences lamb growth and immunological responses (Schiochowski et al., 2010). Nutrition is also a key determinant of the immune response with nutrient deficit influencing several aspects of immunity (Chandra 1997) especially when feed restriction occurs in early life (Schaff et al., 2016; Celi et al., 2018). For example, nutrient restriction (62.5% of ad libitum MR intake) in Assaf female lambs has been associated with enhanced pro-inflammatory conditions in the ileum in preweaning lambs (Frutos et al., 2018b), which was associated with altered liver function and reduced growth rates.

In the current experiment, passive transfer of immunity in the lamb was adequate in all lambs as indicated by GGT levels. Napolitano et al. (1995) reported suppressed immune response in lambs separated from other dams at 2 d of age vs. 15 and 28 d. In the present study, all lambs were removed at the same time from the ewe, therefore no different in immune responsiveness due to the time of removal from the dam is expected. The effect of nutrient restriction coupled with early weaning on the ability of the lamb to produce a normal immune response (immune-competence) was evaluated using an established method to assess the response to a routine vaccination where pre- and postvaccination antibody titers are compared (Zaccaro et al., 2013). Nutrient intake and early weaning of lambs in the present study did not influence the ability of the lambs to mount an immune response to a clostridial vaccine indicating similar immunoresponsiveness. No evidence of weaning stress was evident in either group, as indicated by plasma concentrations of NEFA, which is consistent with the absence of an effect on immune function. While it is not possible to establish whether the level of immunoresponsiveness of the restricted milk-fed lambs in the current experiment were lower compared with ad libitum milk-fed lambs, the results indicate that nutritional status and earlier weaning did not adversely affect the function of the adaptive immune system under the feeding and management regimes employed in this study. These results are consistent with Frutos et al., (2018c) where nutrient restricted artificially reared lambs had similar immune function to naturally reared lambs.

Overall, this study demonstrates that lambs can be successfully weaned off MR by 4 or 6 wk of artificial rearing without compromising growth, small intestine morphology, major organ development, and body composition, nor immune function. Furthermore, artificial rearing of lambs using a restricted MR allowance system (33% less MR) coupled with early access to concentrate and fiber supplementary diets and pasture allowed adequate growth to achieve an average BW of 40 kg (18 kg carcass) at 16 wk of age with similar muscle and fat content. These results highlight the potential to reduce both feed and labor inputs without compromising production performance (as measured by growth and body composition) for rearing of both ewe replacements and lambs for meat production. It is important to acknowledge the low level of health issues and mortality in the present study. Whether similar results could be observed with lower levels of hygiene and/or husbandry practices remains to be established. Furthermore, feeding management during the weaning transition after the removal of the starter and fiber supplements to a pasture-only diet needs to be addressed to avoid a short-term decline in growth rates postweaning.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Ministry of Business Innovation & Employment (MBIE; contract C10X1305) in partnership with Kingsmeade Artisan Cheese, Maui Milk, Spring Sheep Milk Co. and Antara Ag Farms, and New Zealand AID Program and CONACYT and INIFAP in Mexico for stipend support for Omar Cristobal Carballo. A special acknowledgement for the late John Koolaard for his valuable advice and support on experimental design and statistical analysis. The authors also acknowledge the Ulyatt Reid Large Animal Facility Staff at AgResearch Grasslands for their technical support, and assistance from Sarah Lewis, Adrian Molenaar and Sarah MacLean for support with lamb feeding.

References

- AOAC 1990. Official methods of analysis. 15th ed., Arlington, VA: Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 2010. Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 18th ed, Gaithersburg, MD: Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 2012. Official methods of analysis. 19th ed Gaithersburg, MD: Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R. L. 2000. Sheep gastrointestinal development in response to different dietary treatments. Small Rum. Res. 35:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0921-4488(99)00062-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R. L., McLeod K. R., Klotz J. L., and Heitmann R. N.. . 2004. Rumen development, intestinal growth and hepatic metabolism in the pre- and postweaning ruminant. J. Dairy Sci. 87:E55–E65. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)70061-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Beers-Schreurs H. M., Nabuurs M. J., Vellenga L., Kalsbeek-van der Valk H. J., Wensing T., and Breukink H. J.. . 1998. Weaning and the weanling diet influence the villous height and crypt depth in the small intestine of pigs and alter the concentrations of short-chain fatty acids in the large intestine and blood. J. Nutr. 128:947–953. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.6.947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanche A., Cooke J., Jones E., Worgan H. J., and Newbold C. J.. . 2018. Short- and long-term effects of conventional and artificial rearing strategies on the health and performance of growing lambs. Animal. 13:740–749. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118002100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Y. M., and Schlapper R. A.. . 1993. Raising lambs on milk replacer. Proc. Spooner Sheep Day, University of Wisconsin-Madison; p. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt R. S., Tripathi M. K., Verma D. L., and Karim S. A.. . 2009. Effect of different feeding regimes on pre-weaning growth rumen fermentation and its influence on post-weaning performance of lambs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.). 93:568–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2008.00845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimczok D., Röhl F. W., and Ganter M.. . 2005. Evaluation of lamb performance and costs in motherless rearing of German Grey Heath sheep under field conditions using automatic feeding systems. Small Rum. Res. 60(3):255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2004.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breier B. H., Bass J. J., Butler J. H., and Gluckman P. D.. . 1986. The somatotrophic axis in young steers: influence of nutritional status on pulsatile release of growth hormone and circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor 1. J. Endocrinol. 111:209–215. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1110209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E. G., Vandehaar M. J., Daniels K. M., Liesman J. S., Chapin L. T., Forrest J. W., Akers R. M., Pearson R. E., and Nielsen M. S.. . 2005. Effect of increasing energy and protein intake on mammary development in heifer calves. J. Dairy Sci. 88:595–603. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72723-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristobal-Carballo O., Khan M. A., Knol F. W., Lewis S. J., Stevens D. R., Laven R. A., and McCoard S. A.. . 2019. Impact of weaning age on rumen development in artificially reared lambs1. J. Anim. Sci. 97:3498–3510. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso M., Demonte A., and Neves V. A.. . 2012. Histomorphometric study of role of lactoferrin in atrophy of the intestinal mucosa of rats. Health. 4:1362–1370. doi: 10.4236/health.2012.412198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celi P., Verlhac V., Perez Calvo E., Schmeisser J., and Kluenter A.-M.. . 2018. Biomarkers of gastrointestinal functionality in animal nutrition and health. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 250:9–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra R. K. 1997. Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 66(2):460S–463S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.460S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson D. C., Waghorn G. C., Ulyatt M. J., and Lee J.. . 1999. NIRS: forage analysis and livestock feeding. Proc. NZ Grass. Assn. 61:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- David I., Bouvier F., Ricard E., Ruesche J., and Weisbecker J. L.. . 2014. Feeding behaviour of artificially reared Romane lambs. Animal. 8:982–990. doi: 10.1017/S1751731114000603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frutos J., Andrés S., Trevisi E., Yáñez-Ruiz D. R., López S., Santos S., and Giráldez F. J.. . 2018a. Early feed restriction programs metabolic disorders in fattening merino lambs. Animals. 8(6):83. doi: 10.3390/ani8060083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frutos J., Andrés S., Trevisi E., Benavides J., Santos N., Santos A., Giráldez F. J.. . 2018c. Moderated milk replacer restriction of ewe lambs alters gut immunity parameters during the pre-weaning period and impairs liver function and animal performance during the replacement phase. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 243:80–89. doi: 10/1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.07.009 [Google Scholar]

- Frutos J., Andrés S., Yáñez-Ruiz D. R., Benavides J., López S., Santos A., Martínez-Valladares M., Rozada F., and Giráldez F. J.. . 2018b. Early feed restriction of lambs modifies ileal epimural microbiota and affects immunity parameters during the fattening period. Animal. 12:2115–2122. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118000836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gava M. S., Moraes L. B., Carvalho D., Chitolina G. Z., Fallavena L. C. B., Moraes H. L. S., Herpich J., Salle C. T. P.. . 2015. Determining the best sectioning method and intestinal segment for morphometric analysis in broilers. Brazil. J. Poult. Sci. 17(2):145–150. doi: 10.1590/1516-635x1702145-150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geenty K. 2010. Lactation and lamb growth. In: Cottle D. editor. International sheep and wool handbook. Nottingham, UK: University Press; p. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Górka P., Kowalski Z. M., Pietrzak P., Kotunia A., Jagusiak W., and Zabielski R.. . 2011. Is rumen development in newborn calves affected by different liquid feeds and small intestine development? J. Dairy Sci. 94(6):3002–3013. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood P. L., Hunt A. S., Slepetis R. M., Finnerty K. D., Alston C., Beermann D. H., and Bell A. W.. . 2002. Effects of birth weight and postnatal nutrition on neonatal sheep: III. Regulation of energy metabolism. J. Anim. Sci. 80:2850–2861. doi: 10.2527/2002.80112850x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammon H., and Blum J. W.. . 1997. Prolonged colostrum feeding enhances xylose absorption in neonatal calves. J. Anim. Sci. 75:2915–2919. doi: 10.2527/1997.75112915x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney D. P., Shrestha J. N. B., and Peters H. F.. . 1984. Postweaning performance of artificially reared lambs weaned at 21 vs. 28 days of age under two postweaning housing regimens. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 64(3):667–674. doi: 10.4141/cjas84-075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Castellano L. E., Suárez-Trujillo A., Martell-Jaizme D., Cugno G., Argüello A., and Castro N.. . 2015. The effect of colostrum period management on BW and immune system in lambs: from birth to weaning. Animal. 9:1672–1679. doi: 10.1017/S175173111500110X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey M. C., Drennan M., and Earley B.. . 2003. The effect of abrupt weaning of suckler calves on the plasma concentrations of cortisol, catecholamines, leukocytes, acute-phase proteins and in vitro interferon-gamma production. J. Anim. Sci. 81:2847–2855. doi: 10.2527/2003.81112847x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A., Bach A., Weary D. M., and von Keyserlingk M. A. G.. . 2016. Invited review: transitioning from milk to solid feed in dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 99:885–902. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., and Ho S. B.. . 2010. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 12:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0131-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A., Baldwin R. L. VI, and Jesse B. W.. . 2000. Sheep rumen metabolic development in response to age and dietary treatments. J. Anim. Sci. 78:1990–1996. doi: 10.2527/2000.7871990x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane S. F., Magee B. H., and Hogue D. E.. . 1986. Growth, intakes and metabolic responses of artificially reared lambs weaned at 14 d of age. J. Anim. Sci. 63:2018–2027. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.6362018x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl I. L., Sidwell G. M., and Terrill C. E.. . 1972. Performance of artificially reared Finnsheep-cross lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 34:935–939. doi: 10.2527/jas1972.346935x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litherland A. J., and Lambert M. G.. . 2000. Herbage quality and growth rate of single and twin lambs at foot. Proc. NZ Soc. Anim. Prod. 60:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Longenbach J. I., and Heinrichs A. J.. . 1998. A review of the importance and physiological role of curd formation in the abomasum of young calves. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 73:85–97. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(98)00130-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maden M., Altunok V., Birdane F. M., Aslan V., and Nizamlioglu M.. . 2003. Blood and colostrum/milk serum gamma-glutamyltransferase activity as a predictor of passive transfer status in lambs. J. Vet. Med. B. Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 50:128–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2003.00629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick B. C., Thomas D. L., and Berger Y. M.. . 2001. Effect of weaning system on commercial milk production and lamb growth of East Friesian dairy sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 84:1660–1668. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74601-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. M., and Caton J. S.. . 2016. Role of the Small Intestine in Developmental Programming: impact of Maternal Nutrition on the Dam and Offspring. Adv. Nutr. 7:169–178. doi: 10.3945/an.115.010405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir P. S., Shaner A. D., Sorensen B. L.. . 1987. Nutritional performance and intestinal absorptive capacities of neonatal lambs fed milk replacer or dam’s milk, with or without access to creep feed. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 67:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F., Marino V., De Rosa G., Capparelli R., Bordi A.. . 1995. Influence of artificial rearing on behavioural and immune response in lambs. App. Anim. Behav. Sci. 45:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(95)00637-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J., Davies D., and Ridgman W.. . 1969. The effects of varying the quantity and distribution of liquid feed in lambs reared artificially. Anim. Prod. 11(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Penning P. D., and Treacher T. T.. . 1975. The effects of quantity and distribution of milk substitute on the performance and carcass measurements of artificially reared lambs. Anim. Sci. 20(1):111–121. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100016925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pluske J., Hampson D. J., and Williams I. H.. . 1997. Factors influencing the structure and function of the small intestine in the weaned Pig: a review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 51:215–236. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(97)00057-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poe S. E., Glimp H. A., Deweese W. P., and Mitchell G. E. Jr. 1969. Effect of pre-weaning diet on the growth and development of early-weaned lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 28:401–405. doi: 10.2527/jas1969.283401x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2016. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads R. P., Greenwood P. L., Bell A. W., and Boisclair Y. R.. . 2000. Nutritional regulation of the genes encoding the acid-labile subunit and other components of the circulating insulin-like growth factor system in the sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 78:2681–2689. doi: 10.2527/2000.78102681x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos A., Giráldez F. J., Trevisi E., Lucini L., Frutos J., and Andrés S.. . 2018b. Liver transcriptomic and plasma metabolomic profiles of fattening lambs are modified by feed restriction during the suckling period. J. Anim. Sci. 96:1495–1507. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos A., Valdés C., Giráldez F. J., López S., France J., Frutos J., Fernández M., and Andrés S.. . 2018a. Feed efficiency and the liver proteome of fattening lambs are modified by feed restriction during the suckling period. Animal. 12:1838–1846. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118000046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäff C. T., Gruse J., Maciej J., Mielenz M., Wirthgen E., Hoeflich A., Schmicke M., Pfuhl R., Jawor P., Stefaniak T., . et al. 2016. Effects of feeding milk replacer ad libitum or in restricted amounts for the first five weeks of life on the growth, metabolic adaptation, and immune status of newborn calves. PLoS One. 11:e0168974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiochowski C., Moors E., Gauly M.. . 2010. Influence of weaning age and experimental Haemonchus contortus infection on behavior and growth rates of lambs. Applied Anim. Behav. Sci. 125:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2010.04.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi-Beechey S. P., Smith M. W., Wang Y., and James P. S.. . 1991. Postnatal development of lamb intestinal digestive enzymes is not regulated by diet. J. Physiol. 437:691–698. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle N. F. 1996. Non-dietary influences on mineral requirements of sheep. In: Masters D. G. and White C. L editors, Detection and treatment of mineral nutrition problems in sheep. ACIAR Monograph 37, Canberra, pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tan B., Yin Y., Kong X., Li P., Li X., Gao H., Li X., Huang R., and Wu G.. . 2010. L-Arginine stimulates proliferation and prevents endotoxin-induced death of intestinal cells. Amino Acids. 38:1227–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0334-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivey T. R., and Smith M. W.. . 1989. Cytochemical analysis of single villus peptidase activities in pig intestine during neonatal development. J. Histochem. 21:601–608. doi: 10.1007/bf01753361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood E. J., and Suttle N. F.. . 1999. Chapter 11. Copper. In: The mineral nutrition of livestock. 3rd ed Wallingford:CABI Publishing; p. 283–342. [Google Scholar]

- Vente-Spreeuwenberg M. A. M., and Beynen A. C.. . 2003. Diet-mediated modulation of small intestinal integrity in weaned piglets. In Pluske J. R., Le Dividich J., Verstegen M. W. A. editors. Weaning the pig: concepts and consequences. The Netherlands:Wageningen Academic Publishers; p. 145–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccaro D. J., Wagener D. K., Whisnant C. C., and Staats H. F.. . 2013. Evaluation of vaccine-induced antibody responses: impact of new technologies. Vaccine. 31:2756–2761. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]