Abstract

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross is credited as one of the first clinicians to formalize recommendations for working with patients with advanced medical illnesses. In her seminal book, On Death and Dying, she identified a glaring gap in our understanding of how people cope with death, both on the part of the terminally ill patients that face death and as the clinicians who care for these patients. Now, 50 years later, a substantial and ever-growing body of research has identified “best practices” for end of life care and provides confirmation and support for many of the therapeutic practices originally recommended by Dr. Kübler-Ross. This paper reviews the empirical study of psychological well-being and distress at the end of life. Specifically, we review what has been learned from studies of patient desire for hastened death and the early debates around physician assisted suicide, as well as demonstrating how these studies, informed by existential principles, have led to the development of manualized psychotherapies for patients with advanced disease. The ultimate goal of these interventions has been to attenuate suffering and help terminally ill patients and their families maintain a sense of dignity, meaning, and peace as they approach the end of life. Two well-established, empirically supported psychotherapies for patients at the end of life, Dignity Therapy and Meaning Centered Psychotherapy are reviewed in detail.

Keywords: end of life, psychotherapy, dignity, meaning, existential

“We are always amazed how one session can relieve a patient of a tremendous burden […] it often requires nothing more but an open question.”

–Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 1969, p. 242

Introduction

Are there particular things that you feel still need to be said to your loved ones, or things that you would want to take the time to say once again? What is a good and meaningful death? These are just two examples of the psychotherapy question prompts that comprise today’s most well-established, empirically supported psychotherapies for patients with advanced and terminal illnesses (Breitbart et al., 2015; Breitbart et al., 2018; Chochinov et al., 2005a; Chochinov et al., 2011). These therapeutic prompts were developed out of a long line of rich clinical and research knowledge that facilitated a deeper understanding of the psychological and existential needs of patients facing death.

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross is credited as one of the first clinicians to formalize recommendations for working with patients with advanced medical illness. In her seminal book, On Death and Dying, Dr. Kübler-Ross provided explicit, previously elusive guidance on how to openly broach the topic of death at the bedside. She wrote “It might be helpful if more people were to talk about death and dying as an intrinsic part of life just as they do not hesitate to mention when someone is expecting a new baby” (1969, 126). In writing specifically about psychotherapy with the terminally ill, Dr. Kübler-Ross expressed a profound clinical and human understanding of these patients: “it is evident that the terminally ill patient has very special needs which can be fulfilled if we take time to sit and listen and find out what they are. The most important communication, perhaps, is the fact that we let him know we are ready and willing to share some of his concerns” (1969, 241). Now, 50 years later, a substantial and ever-growing body of research has helped clarify best practices for end-of-life care, supporting many of the therapeutic practices originally described by Dr. Kübler-Ross. This paper reviews the empirical study of psychological wellbeing and distress at the end of life, documenting what has been learned from research on the desire for hastened death, particularly during the late 20th century debates around physician assisted suicide. In turn, these studies, which were often informed by existential principles, have led to the development of several manualized psychotherapies for patients with advanced disease, with the goal of attenuating suffering and helping patients and their families maintain a sense of dignity, meaning, and peace at the end of life.

Shortly after Dr. Kübler-Ross began to write about her work with patients who were dying, experts in group psychotherapy began to develop systematic interventions for helping these individuals. For example, Irvin Yalom (1980), who was heavily influence by existential philosophy, conceptualized four “ultimate concerns” of life: death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness. His writings and clinical insights into working with patients who were facing death formed the basis for what eventually became Supportive Expressive Group Psychotherapy (SEGT; Spiegel, Bloom, & Yalom 1981; Spiegel & Yalom, 1978; Yalom & Greaves, 1997). Although their early research was limited to women with metastatic breast cancer, SEGT was one of the first psychotherapy approaches that was specifically aimed at providing patients with advanced cancer with the type of supportive environment that could help buffer what was seen as the trauma of a terminal illness. More importantly, this early research challenged the previous thinking, that convening a group of patients with terminal illness would be an entirely demoralizing experience (Spiegel & Glafkides, 1983). Over the next several decades, research in the areas of palliative care and patients’ existential needs at the end of life, as well as the role of mental health providers in these settings, expanded dramatically. In part, this course of research was fueled by the changing ethical and legal contours of physician assisted suicide.

Desire for Hastened Death

In the late twentieth century, debates regarding physician assisted death (PAD; i.e., physician assisted suicide, euthanasia) generated considerable interest from researchers who sought to understand why some patients with terminal illness might want to hasten death. The term desire for hastened death (DHD) was developed as a way of studying what was thought to be the construct underlying both requests for assisted death and thoughts of suicide more generally (Brown et al., 1986; Chochinov et al., 1995; Rosenfeld et al., 1999). Initially, pain, depression, and physical symptoms were hypothesized to be the main drivers of DHD, generating considerable emphasis on improving palliative care in hopes of reducing or eliminating requests for PAD. However, the research literature that emerged in the 1990’s and early 2000’s has placed much more emphasis on psychological and existential correlates of PAD, such as depression, hopelessness, spiritual well-being and perception of oneself as a burden to others. This evolving research literature has provided an empirical basis for an ever growing number of psychotherapy interventions for patients at the end of life, most of which assume that while adequate physical symptom control is likely, addressing the psychological and spiritual needs of patients with serious or terminal illness is more challenging.

One of the seminal studies of DHD, conducted by Breitbart and colleagues (2000) evaluated the factors associated with DHD in a sample of 92 patients who had been hospitalized in a palliative care facility, all of whom had been diagnosed with terminal cancer and had a life expectancy of 6 months or less. They found that 17 percent of the study participants met diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode, according to a clinician-administered semi-structured interview. Similarly, 17 percent of participants also endorsed a high DHD (using a self-report rating scale that had been developed by the study investigators). Perhaps not surprisingly, those with a major depressive episode were four times more likely to endorse DHD than those without MDD, but they found that hopelessness was an equally, if not more important predictor of DHD, and the presence of both depression and hopelessness had an even more powerful impact on DHD. In addition to depression and hopelessness, other risk factors for DHD that this study identified included spiritual well-being, overall quality of life, and the perception of being a burden to others. Although severity of physical symptoms and symptom distress were also significant predictors of DHD, pain and pain intensity were not. These findings aligned with and extended earlier work in which hopelessness was found to uniquely contribute to predicting suicidal ideation after controlling for depression in patients with advanced terminal cancer (Chochinov et al., 1998). In subsequent analyses, McClain, Rosenfeld, and Breitbart (2003) found that spiritual wellbeing, and a sense of meaning and purpose in particular, actually buffered the effects of depression on DHD and suicidal ideation, highlighting yet another potentially important psychological/existential construct. These studies have fueled a growing interest in clinical interventions that not only target depression, but also focus more directly on hopelessness and spiritual well-being.

Simultaneous to the emerging research on hopelessness and spiritual wellbeing, Chochinov and his colleagues (2002a) began to examine the loss of dignity as a critical risk factor for DHD. In their first study focused on the importance of dignity, these authors found, in a sample of 213 patients with terminal cancer, that patients who reported feeling a loss of dignity due to advancing illness were not only more likely to report worse psychological and physical symptom distress, but were also more likely to acknowledged having lost their “will to live.” In a subsequent study focused squarely on the will to live, Chochinov et al. (2005b) found that key existential issues such as a lost sense of dignity, perceiving oneself to be a burden to others, and feelings of hopelessness were more strongly related to DHD than physical symptoms. Collectively, these studies have provided empirical support for what had long been suspected by mental health practitioners working with the terminally ill – that losing one’s hope is analogous to losing a sense of meaning and purpose, contributing to a diminished loss of the will to live in the face of terminal illness. Conversely, the preservation of dignity can help preserve an individual’s sense that they are valued and by extension, could improve a patient’s will to live at the end of life (Chochinov et al., 2005b). In short, the findings from these and other studies have identified a number of critical concerns for patients at the end of life and have generated a range of potential targets for psychotherapeutic interventions that might ameliorate DHD and preserve the will to live.

Dignity Model and Dignity Therapy (DT)

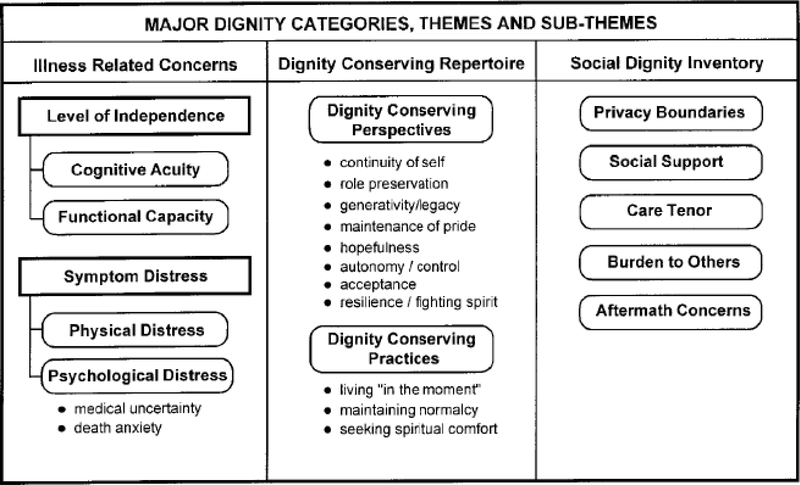

A primary goal of palliative care is to help patients die with dignity. This goal is traditionally achieved through symptom management, but has increasingly encompassed psychological, spiritual, and family care. Chochinov and colleagues (2002a) proposed that dignity can provide an overarching framework to guide patients, families, and health care professionals in defining the goals and preferences for end-of-life care. Influenced in part by the aforementioned DHD studies, Chochinov (2002b; 2013; Sinclair et al., 2016) is well known as an advocate for dignity-preserving, compassionate end-of-life care. He proposed a model of dignity that was based on both clinical experience and a series of qualitative interviews with patients who were in an advanced stage of terminal cancer (see Figure 1). Three broad areas emerged as critical elements of dignity conservation in end-of-life care: 1) illness-related concerns, 2) a dignity-conserving repertoire, and 3) social aspects of dignity. Broadly, illness-related concerns include aspects of the illness itself such as symptom-related distress or functional impairment. Dignity-conserving repertoire includes both maintaining a dignity-conserving perspective (i.e., ways of looking at one’s situation that helps promote dignity and maintain a sense of personhood) as well as dignity-conserving practices, or techniques that can be implemented to maintain dignity. Finally, the social elements of dignity include interpersonal and relationship attributes that can either enhance or diminish one’s dignity (e.g., privacy, perceived burdensomeness, aftermath concerns). Critical to this model is the understanding that each individual possesses unique differences and personal attributes, and that acknowledging these characteristics is fundamental to dignity preservation. Chochinov also developed question prompts that were linked to various facets of the model and offer guidance to clinicians on how to achieve dignity conserving care. These prompts serve as key guideposts in Dignity Therapy (DT).

Figure 1.

Dignity Model

Dignity Therapy (DT) was one of the first manualized psychotherapy interventions developed specifically for use in palliative care settings (Chochinov et al., 2005a; 2011). In DT, patients with a terminal illness (i.e., across a range of conditions, not only those with cancer) are invited to discuss aspects of their life they would most want recorded and remembered. Patients are told in advance that they will be asked by the therapist to speak about things that matter the most to them, including things they may want to share with their closest friends and family. These audiotaped discussions are guided by a framework of questions (see Table 1) that were based on the dignity model, and are provided in advance of the session, in order to give the individual time to reflect on the questions and their answers. The individual is then guided through a flexible (i.e., semi-structured) interview in which the therapist uses the question framework to facilitate the disclosure (and recording) of the person’s thoughts, feelings, and memories. Typically, this process is completed within a single session, but can be completed across several meetings, if need be. The audiotaped interviews are then transcribed and edited into a narrative in order to prepare a legacy or generativity document. In the second session, this document is presented to the patient and reviewed, allowing them the opportunity to suggest edits or make any desired changes. The final document is then given to the patient, allowing them the opportunity to share it with loved ones, if they choose to. In hopes of engendering a sense of generativity, one of the main goals of DT is to help patients feel that they will have left something of value behind. The therapeutic goal is to enhance a sense of meaning and purpose for patients, helping them to identify their lasting legacy and in so doing, contribute to preserving their dignity.

Table 1.

Dignity Therapy Question Protocol

| • “Tell me a little about your life history, particularly the parts that you either remember most, or think are the most important. When did you feel most alive?” |

| • “Are there specific things that you would want your family to know about you, and are there particular things you would want them to remember?” |

| • “What are the most important roles you have played in life (family roles, vocational roles, community service roles, etc.)? Why were they so important to you, and what do you think you accomplished in those roles?” |

| • “What are your most important accomplishments, and what do you feel most proud of?” |

| • “Are there particular things that you feel still need to be said to your loved ones, or things that you would want to take the time to say once again?” |

| • “What are your hopes and dreams for your loved ones?” |

| • “What have you learned about life that you would want to pass along to others? What advice or words of guidance would you wish to pass along to your (son, daughter, husband, wife, parents, others)?” |

| • “Are there words or perhaps even instructions you would like to offer your family to help prepare them for the future?” |

| • “In creating this permanent record, are there other things that you would like included?” |

An initial feasibility study of DT included adults receiving home-based palliative care services in Canada and Australia (Chochinov et al., 2005a). Eligibility for this study included being 18 years or older, having a terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 6 months, English speaking, a willingness to commit to 3 to 4 contacts over 7 to 10 days, and no obvious cognitive impairment that might impede participation. Prior to participating in the pilot study, the participants completed a series of questionnaires about their physical, psychological, and existential well-being. Study participants then completed the DT process, following the procedures described above, and were then asked to complete the outcome measures again, along with a survey intended to elicit satisfaction with the DT intervention. Of the 100 patients who participated in the initial study, 91 percent reported feeling satisfied or highly satisfied with DT, and 86 percent described it as helpful or very helpful. Existential outcomes were also rated as improved, as 76 percent reported an increased sense of dignity, 68 percent reported an increased sense of purpose, and 67 percent reported increased sense of meaning. Nearly half also indicated that their will to live increased following DT. Significant treatment effects were also observed for suffering and depressed mood (i.e., significant reductions following study completion), and those participants who reported greater despair and distress at baseline appeared to demonstrate the greatest benefits from DT. A subsequent randomized controlled trial (RCT) of DT compared to supportive client-centered care or standard care (n = 441) also found promising trends that supported DT (Chochinov et al., 2011). Specifically, participants reported that DT increased their sense of dignity and quality of life, and felt it had been or would be of benefit to their family (compared to the other study arms).

Following the initial reports about DT, numerous research studies have been implemented and evaluated around the world. A 2017 systematic review of DT included 28 articles that had been published between 2011 and 2016 (Martínez et al., 2017). Overall, the quality of the studies was rated as high, with five RCTs of DT. In the two RCTs that included patients with high baseline levels of distress, one (Juliao et al., 2015) demonstrated statistically significant decreases in patients’ anxiety and depression scores over time, while the other (Rudilla et al., 2016) demonstrated significant decreases in anxiety but not depression. As with the initial DT feasibility study, uncontrolled replication studies have also demonstrated significant improvement for patients across psychological and existential outcomes (Martínez et al., 2017). Despite the overwhelming positive evaluation of DT provided by patients and families across DT studies, future RCTs are still needed to determine whether DT is more (or less) appropriate and beneficial for identifiable subgroups of terminally ill patients (e.g., those experiencing high levels of distress), and to more systematically evaluate the mechanism of change observed in pre-post intervention outcome measures.

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy (MCP)

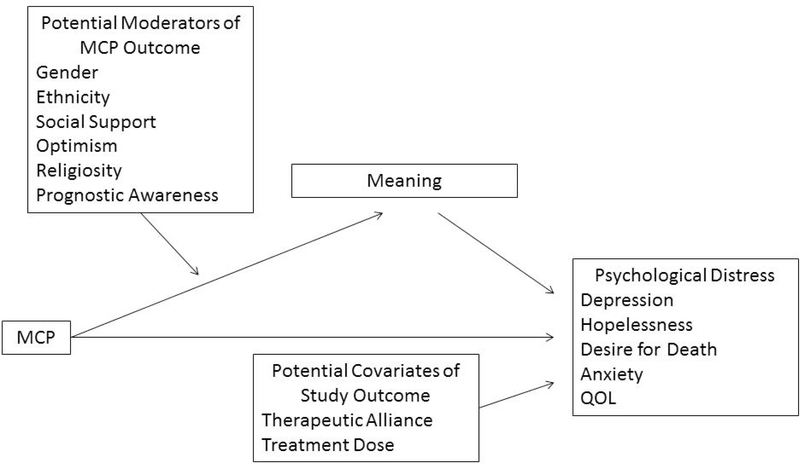

Unlike Dignity Therapy’s focus on generativity and legacy, Breitbart and his colleagues (2000, 2002, MANUALS) developed a more traditional psychotherapy approach to helping patients cope with the challenges of terminal illness. Inspired primarily by the works of Viktor Frankl (1955; 1959; 1969), and his emphasis on the importance of meaning in human existence, Meaning Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) was initially conceived of as a group-based intervention for individuals with advanced cancer. MCGP draws heavily from Frankl’s concepts, by identifying the sources of meaning as a resource to help patients develop or sustain a sense of meaning and purpose, even while in the midst of suffering. In addition, MCGP incorporates a number of fundamental existential concepts and concerns related to the search, connection, and creation of meaning (Park & Folkman, 1997). In short, enhanced meaning is conceptualized as the catalyst for improved psychosocial outcomes, such as improved quality of life, reduced psychological distress, and a decreased sense of despair (see Figure 2). Hence, meaning is viewed as both an intermediary outcome, as well as a mediator of changes in these important psychosocial outcomes (Rosenfeld et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy Conceptual Model

Although originally developed as a group-based intervention, Meaning Centered Psychotherapy was subsequently adapted to permit delivery in an individualized format (Breitbart et al. 2012; 2018). This adaptation is particularly important for those individuals with very advanced disease, where physical limitation and/or treatment needs may limit the ability to attend regularly scheduled group sessions. The structure of the Individual Meaning Centered Psychotherapy (IMCP) is similar except in the group version, with the exception of the initial sessions dedicated to learning about patients’ cancer stories (only one such session is needed for IMCP, rather than two for MCGP). Thus, IMCP is a seven-session, manualized intervention that focuses on specific themes related to meaning and the experience of having advanced cancer. Both versions of Meaning Centered Psychotherapy have three overarching goals: 1) to promote a supportive environment for patients to explore personal issues and feelings surrounding their illness on a therapeutic basis; 2) to facilitate a greater understanding of possible sources of meaning both before and after a diagnosis of cancer; and 3) to aid patients in their discovery and maintenance of a sense of meaning in life even as the illness progresses. In short, MCGP and IMCP were designed to help patients optimize coping through an enhanced sense of meaning and purpose. Moreover, the intervention is intended to help broaden the scope of possible sources of meaning through a combination of: 1) educating patients in the philosophy of meaning on which the intervention is based, 2) in-session exercises and between-session homework that each participant is asked to complete, and 3) open-ended discussions, which typically include the therapist’s interpretive insights and comments. Table 2 presents a list of session topics, including an outline of the sources of meaning (i.e., historical, attitudinal, creative, and experiential).

Table 2.

Topics of Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (IMCP) Weekly Sessions

| Session | IMCP Topic | Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concepts & Sources of Meaning | Introduction of Concept of Meaning and Sources of Meaning |

| 2 | Cancer and Meaning | Identity – Before and After Cancer Diagnosis; Meaningful Moments |

| 3 | Historical Sources of Meaning & Legacy: Past, Present & Future | Life as a Legacy Given (Past), Lives (Present) and Gives (Future) |

| 4 | Attitudinal Sources of Meaning:Encountering Life’s Limitations | Confronting the Limitations of Cancer, Prognosis and Death |

| 5 | Creative Sources of Meaning:Engaging in Life | Creativity, Courage and Responsibility |

| 6 | Experiential Sources of Meaning:Connecting with Life Now | Love, Nature, Art, and Humor; Connection |

| 7 | Transitions: Reflections, & Hopes | Reflections on Lessons Learned and Hopes for the Future |

To date, four RCTs conducted by Breitbart and colleagues (2010, 2012, 2015, 2018) have examined the efficacy of MCP in patients with advanced cancer in the outpatient, ambulatory care setting. The first pilot study of MCGP provided strong support for the efficacy of this intervention, not only improving spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning, but also in decreasing anxiety, hopelessness, physical symptom distress, and DHD (Breitbart et al., 2010). In that study, 90 patients were randomly assigned to receive either 8 eight sessions of MCGP or Supportive Group Psychotherapy (SGP). Results of this study demonstrated significantly greater benefits from MCGP compared to SGP, with the strongest effects for enhanced spiritual well-being and sense of meaning. Importantly, treatment effects for MCGP appeared even stronger two months after treatment ended, suggesting that benefits may not only persist but even grow after treatment is completed. On the other hand, participants who received SGP did not demonstrate any such improvements in spiritual well-being, quality of life, or psychological distress at either post-treatment or the follow-up assessment. This study provided initial support for the benefits of MCGP as a novel intervention for improving spiritual well-being and sense of meaning, and fueled interest in this intervention as a potentially efficacious treatment for end-of-life despair. A second pilot RCT tested the individualized format of Meaning Centered Psychotherapy, IMCP, in 120 patients with advanced cancer (Breitbart et al., 2012). In that study, IMCP again demonstrated significant treatment effects in improving spiritual well-being, sense or meaning, and overall quality of life, while also reducing hopelessness, DHD, depression, and physical symptom distress. Two subsequent RCTs, one investigating MCGP (Breitbart et al., 2015) and a second examining IMCP (Breitbart et al., 2018), have replicated and extended the results of the initial pilot study findings in substantially larger samples (N = 253 and N=325, respectively). These studies, totaling nearly 800 patients in randomized clinical trials, have provided strong support for the effectiveness of Meaning Centered Psychotherapy in improving spiritual well-being and reducing psychological distress.

Although the emerging research on Meaning Centered Psychotherapy has supported its effectiveness, and has consistently demonstrated that supportive psychotherapy, while frequently used in medical settings is largely ineffective, the extent to which the observed results are due to changes in one’s sense of meaning require further evidence. Recently, Rosenfeld and colleagues (2018) provided such evidence in their examination of the mechanism of change in MCGP. Using data from drawn from two RCTs of MCGP (Breitbart et al., 2010, 2015), they used structural equation modeling to evaluate the mediation effects of treatment type on key psychosocial outcomes (e.g., quality of life, depression, hopelessness, and DHD). Specifically, they demonstrated that post-treatment changes in psychosocial outcomes were mediated by changes in the patient’s sense of meaning and peace. These analyses are some of the first to empirically evaluate the hypothesized mechanism of change in these types of existential psychotherapies for patients with advanced medical illnesses, and provides empirical support for the theoretical foundation underlying this psychotherapy approach.

Like Dignity Therapy, enthusiasm for Meaning Centered Psychotherapy has fueled multiple adaptations of this treatment approach, in order to target unique clinical populations and settings. These adaptations have included cancer survivors, bereaved family members, and caregivers (Applebaum, Kulikowski, & Breitbart, 2015; Lichtenthal et al., 2019; van der Spek et al., 2017). In addition, several “cultural” adaptations of MCGP have been developed and/or pilot tested in samples ranging from Latin and Chinese immigrants in the United States to individuals from Israel, Spain, the Netherlands (e.g., Costas-Muñiz et al., 2017; Gi,l Fraguell & Limonero, 2017; Goldzweig, et al., 2017; Leng et al, 2018). Further, given the unique needs of palliative care patients, many of whom cannot realistically complete a 7-session intervention (e.g., due to deteriorating cognitive and physical functioning), Rosenfeld and colleagues developed a 3-session version of IMCP that was intended to be delivered at the bedside for patients in the final weeks of life (Rosenfeld et al., 2017). Their small feasibility study demonstrated promise for this abbreviated version of IMCP, but more systematic research is needed to determine whether this intervention can be effectively delivered in a highly condensed format. In addition, while virtually all research examining Dignity Therapy and Meaning Centered Psychotherapy have focused on oncology settings, the potential for the core principles of these interventions to help patients with other advanced diseases is clear. Thus, future research should focus on examining the utility of these interventions for patients with a range of other advanced and terminal illnesses.

Other Interventions for Adults with Terminal Illness

Although Dignity Therapy and Meaning Centered Psychotherapy have garnered the most attention in the fields of palliative care and psycho-oncology, several other researchers and clinicians have developed interventions for this vulnerable population. For example, Ando and colleagues (Ando et al., 2008, 2010) proposed a treatment approach, called Short-Term Life Review (STLR), that has structural similarities to Dignity Therapy. Like Dignity Therapy, STLR also consists of an initial interview focusing on important memories, relationships, and messages for younger generations. This interview is used to create an album that is reviewed with the patient in a second session. The difference between these two approaches (DT and STLR) lies primarily in the substance of the interview. However, unlike DT, there has been little research to support the STLR approach, with a single published RCT examining its utility. This study (Ando et al., 2010) demonstrated that patients with terminal cancer who received STLR showed greater increases in spiritual wellbeing, sense of hope, and preparedness for death compared to patients who received two sessions of general support.

Another brief, structured intervention for patients with advanced and/or terminal cancer is Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM; Hales, Lo & Rodin, 2015; Nissim et al., 2012). Drawing on some of the same underlying principles as MCGP (e.g., the importance of spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning), CALM also focuses on identifying and navigating changes in self and relations with close others, symptom management and communication with health care providers, and advance care planning. The intervention is delivered in three to six sessions over a three-month period, therefore providing less emphasis on spiritual well-being and related existential issues (because the intervention content also encompasses a range of other important foci). However, preliminary research has supported the effectiveness of this intervention, beginning with Lo and colleagues’ (2014) pilot study of 50 Canadian palliative care patients. In that study, those who completed CALM reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression and death anxiety, and significantly better overall quality of life, compared to those who did not complete the intervention. More recently, Rodin and colleagues (2018) described the first large-scale RCT of CALM in their study of 305 individuals receiving outpatient cancer care. Patients randomized to CALM demonstrated significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms and overall quality of life for patients randomized to CALM compared to those receiving usual care, but no difference in changes in anxiety, spiritual well-being, or death anxiety. Although encouraging, these interventions require further study before firm conclusions can be drawn about their effectiveness and relative efficacy compared to more well-established interventions such as Dignity Therapy and MCGP.

The aforementioned interventions, as well as others that are not described in this review, were synthesized in a recent meta-analysis that summarized 24 RCTs that addressed interventions that primarily focus on existential issues in adults with cancer (Bauereiß et al., 2018). This review identified the strongest effects for these treatments on measures of existential wellbeing, quality of life, and hope/hopelessness. However, only the treatment effects for hope were sustained at six months, though significant effects on self-efficacy also emerged at the 6-month time point. Surprisingly, treatment effect sizes for spiritual well-being, depression, and anxiety, were small. Notably, the analyses did not identify any moderator effects for cancer stage or type, suggesting that despite the heterogeneity of the cancer experience, existential distress may be an appropriate treatment target across the cancer continuum. Finally, Bauereiß et al., (2018) highlighted several future directions for research addressing interventions at the end of life, such as striving towards greater standardization of outcome metrics and ways of lowering the resource intensity of the interventions (e.g., telehealth adaptations).

Future Directions

The history reviewed here only scratches the surface of the palliative and end of life care literature, which continues to grow. For psychotherapeutic interventions in particular, it is critically important that researchers determining how to optimize training and dissemination efforts of evidence-based psychotherapies (e.g., Dignity Therapy, Meaning Centered Psychotherapy, CALM). As the world population continues to diversify, efforts to adapt these treatments to various cultures are critical to developing culturally responsive interventions. Similarly, as the world population ages, heterogeneity in chronic and terminal illnesses is also likely to increase, so determining the relative efficacy of these psychotherapies for different patient groups (beyond cancer) should be prioritized. As first recommended by Kubler-Ross, communications that include open, honest discussions of illness and prognosis between clinicians, patients, and families, continues to be critical, particularly as they facilitate informed treatment decisions and enhance end of life care. Finally, the growing adoption of physician assisted death (PAD) in more and more jurisdictions requires mental health providers be prepared to discuss PAD with their patients and the potential existential questions that may accompany its consideration. Clinicians must also be competent to deliver psychotherapeutic interventions, targeting various sources of existential distress, to patients who are coping with a terminal illness.

Conclusions

This review provides a window into the progression of psychotherapy research with patients at the end of life that began in the aftermath of Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s seminal book. While the content, structure, and empirical foundation underlying end of life psychotherapies have evolved considerably in the 50 years since that book’s publication, her recommendations for providing a nonjudgmental space for open discussion of fears and concerns around death and dying remains a cornerstone of these interventions. Whether through Dignity Therapy, Meaning Centered Psychotherapy, or other interventions that draw on existential principles, patients who are navigating the demands of an uncertain future both require and deserve state of the art interventions. The goal of attenuating suffering and helping patients and their families to maintain a sense of meaning, dignity and peace is central to this work.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants T32CA009461, and P30CA008748.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Rebecca M. Saracino, Assistant Attending Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Barry Rosenfeld, Professor and Chair, Department of Psychology, Adjunct Professor, School of Law, Fordham University, Bronx NY 10458, Past-President, International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services.

William Breitbart, Chairman, Jimmie C. Holland Chair in Psychiatric Oncology, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Harvey Max Chochinov, Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry, University of Manitoba.

References

- 1.Kübler-Ross E (1969). On Death and Dying, Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando M, Morita T, Okamoto T, and Ninosaka Y. (2008). One‐week Short‐Term Life Review interview can improve spiritual well‐being of terminally ill cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncology 17: 885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Okamoto T, and Japanese Task Force for Spiritual Care. (2010). Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 39: 993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, and Breitbart W. 2015. Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and overview. Palliative & supportive care 13: 1631–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders : DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauereiß N, Obermaier S, Özünal SE, and Baumeister H. (2018). Effects of existential interventions on spiritual, psychological, and physical well‐being in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psycho‐oncology 27: 2531–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kaim M, Funesti-Esch J, Galietta M, Nelson CJ, and Brescia R. (2000). Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 284: 2907–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Applebaum A, Kulikowski J, and Lichtenthal WG. (2015). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: an effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33: 749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breitbart W, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal WG, Li Y, Saracino RM et al. (2018). Individual meaning‐centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: A randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 124: 3231–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JH, Henteleff P, Barakat S, and Rowe CJ. (1986). Is it normal for terminally ill patients to desire death? The American Journal of Psychiatry 143: 208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chochinov HM (2002b). Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA 287: 2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, and Harlos M. 2002a. Dignity in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional, cohort study. The Lancet 360: 2026–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chochinov HM (2013). Dignity in care: time to take action. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 46: 756–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, and Harlos M. (2011). Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology 12: 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, and Harlos M. (2005a). Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23: 5520–5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, and Harlos M. 2005b. Understanding the will to live in patients nearing death. Psychosomatics 46: 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Mowchun N, Lander S, Levitt M, and Clinch JJ. (1995). Desire for death in the terminally ill. The American Journal of Psychiatry 152: 1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chochinov Harvey Max, Wilson Keith G., Enns Murray, and Lander Sheila. (1998). Depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 39: 366–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankl VF 1955. The doctor and the soul. New York, NY: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankl VF 1959. Man’s Search for Meaning, fourth edition. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankl VF (1969). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy, expanded edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hales S, Lo C, Rodin G. Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM) Treatment Manual: An Individual Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julião M, Barbosa A, Oliveira F, Nunes B, and Carneiro AV. (2013). Efficacy of dignity therapy for depression and anxiety in terminally ill patients: early results of a randomized controlled trial. Palliative & supportive care 11: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kübler-Ross E (1969). On Death and Dying. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtenthal WG, Catarozoli C, Masterson M, Slivjak E, Schofield E, Roberts KE, Neimeyer RA et al. (2019). An open trial of meaning-centered grief therapy: Rationale and preliminary evaluation. Palliative & supportive care 17: 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo C, Hales S, Jung J, Chiu A, Panday T, Rydall A, Nissim R et al. (2014). Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): phase 2 trial of a brief individual psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Palliative medicine 28: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez M, Arantzamendi M, Belar A, Carrasco JM, Carvajal A, Rullán M, and Centeno C. 2017. ‘Dignity therapy’, a promising intervention in palliative care: A comprehensive systematic literature review.” Palliative medicine 31: 492–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, and Breitbart W. (2003). Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. The Lancet 361: 1603–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nissim R, Freeman E, Lo C, Zimmermann C, Gagliese L, Rydall A, Hales S, and Rodin G. (2012). Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): a qualitative study of a brief individual psychotherapy for individuals with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine 26: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park C and Folkman S (1997). Meaning in the context of Stress and Coping. Review of General Psychology 1: 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, Funesti-Esch J, Kaim M, Krivo S, and Galietta M. 1999. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/AIDS: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. American Journal of Psychiatry 156: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld B, Cham H, Pessin H, and Breitbart W. (2018). Why is Meaning‐Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) effective? Enhanced sense of meaning as the mechanism of change for advanced cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncology 27: 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenfeld B, Saracino R, Tobias K, Masterson M, Pessin H, Applebaum A, Brescia R, and Breitbart W. (2017). Adapting meaning-centered psychotherapy for the palliative care setting: results of a pilot study. Palliative Medicine 31: 140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudilla D, Galiana L, Oliver A, and Barreto P. (2016). Comparing counseling and dignity therapies in home care patients: A pilot study. Palliative & supportive care 14: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinclair S, McClement S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Hack TF, Hagen NA, McConnell S, and Chochinov HM. (2016). Compassion in health care: an empirical model. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 51: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, and Yalom I. (1981). Group support for patients with metastatic cancer: A randomized prospective outcome study. Archives of general psychiatry 38: 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiegel D, and Glafkides MC. (1983). Effects of group confrontation with death and dying. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 33: 433–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spiegel D, and Yalom ID. (1978). A support group for dying patients. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 28: 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Spek N, Vos J, van Uden-Kraan CF, Breitbart W, Cuijpers P, Holtmaat K, Witte BI, Tollenaar RA, and Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. (2017). Efficacy of meaning-centered group psychotherapy for cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial.” Psychological medicine 47: 1990–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yalom ID (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yalom ID and Greaves C. (1977). Group therapy with the terminally ill. The American Journal of Psychiatry 134: 396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]