Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia is usually considered an illness of young adulthood. However, onset after the age of 40 years is reported in 23% of patients hospitalised with schizophrenia. At least 0.1% of the world's elderly population have a diagnosis of late‐onset schizophrenia which seems to differ from earlier onset schizophrenia on a variety of counts including response to antipsychotic drugs.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antipsychotic drugs for elderly people with late‐onset schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (January 2010) which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. We inspected references of all identified studies for further trials. We contacted relevant authors of trials for additional information.

We updated this search Janurary 2013 and added 48 new trials to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

All relevant randomised controlled trials that compared antipsychotic drugs with other treatments for elderly people (at least 80% older than 65 years) with a recent (within five years) diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia like illnesses.

Data collection and analysis

For the 2010 search, two new review authors (AE, AG) inspected all citations to ensure reliable selection. We assessed methodological quality of trials using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. AE and AG also independently extracted data. For homogenous dichotomous data, we planned to calculate the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Main results

There were no included studies in the original version of this review (2002 search). The 2010 search for the current update produced 211 references, among which we identified 88 studies. Only one study met the inclusion criteria and was of acceptable quality. This was an eight‐week randomised trial of risperidone and olanzapine in 44 inpatients with late‐onset schizophrenia. All participants completed the eight‐week trial, indicating that both drugs were well tolerated. Unfortunately, this study provided little usable data. We excluded a total of 81 studies, 77 studies because they either studied interventions other than antipsychotic medication or because they involved elderly people with chronic ‐ not late‐onset ‐ schizophrenia. We excluded a further four trials of antipsychotics in late‐onset schizophrenia because of flawed design. Five studies are still awaiting classification, and one is on‐going.

Authors' conclusions

There is no trial‐based evidence upon which to base guidelines for the treatment of late‐onset schizophrenia. There is a need for good quality‐controlled clinical trials into the effects of antipsychotics for this group. Such trials are possible. Until they are undertaken, people with late‐onset schizophrenia will be treated by doctors using clinical judgement and habit to guide prescribing.

Note: the 48 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Keywords: Aged, Female, Humans, Male, Middle Aged, Age of Onset, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use, Olanzapine, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risperidone, Risperidone/therapeutic use, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Antipsychotic drugs for elderly people with late‐onset schizophrenia

A significant proportion of the world's growing elderly population suffers from schizophrenia that started very late in life. Antipsychotic drugs are often used to treat this distressing and severe illness. In this review we attempted to find good quality trial‐based evidence to support this practice but found none. Currently this vulnerable group is not well served by the research community.

Background

Description of the condition

Although schizophrenia is commonly thought of as an illness of young adulthood, it can both extend into and first appear in later life. It has been recognised that schizophrenia may have a late‐onset ever since schizophrenia was first described (Kraepelin 1909), and contemporary diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, such as DSM‐IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and ICD‐10 (International Classification of Diseases), place no restrictions on age of onset for a diagnosis to be made.

Variously referred to as paraphrenia, late paraphrenia, paranoia, involutional paranoid disorder and late‐onset schizophrenia, there has been no general agreement on the definition of late onset. Different studies defined late‐onset as onset after 40, 45, 60, or 65 years of age (Harris 1988). The International Late‐Onset Schizophrenia Group Consensus Statement recommended the diagnoses of late‐onset schizophrenia (illness onset after 40 years of age) and very‐late‐onset schizophrenia‐like psychosis (onset after 60 years) (Howard 1992b; Howard 1993; Howard 2000). The diagnosis of late‐onset schizophrenia is further complicated by the fact that it is often difficult to determine the age of onset of schizophrenia, especially in older people (Harris 1988a).

At least 12% of elderly people in the community have mental disorders, and about 0.1% of them have a diagnosis of late‐onset schizophrenia (Regier 2000). Only 5.7% of people with late‐onset schizophrenia‐like psychosis live in their own home and 24% live in sheltered accommodation (Henderson 1998). Twenty‐three per cent of patients hospitalised for schizophrenia were reported to have had onset of their illness after the age of 40; 13% in their forties, 7% in their fifties, and 3% after age 60 (Harris 1988). The prevalence of late‐onset schizophrenia‐like psychosis within a community has been reported to be as high as 7.5% (Henderson 1998). The estimated one‐year prevalence rate of schizophrenia in individuals between ages 45 and 64 is 0.6% (Keith 1991), and between 0.1% to 0.5% in individuals over 65 years of age (Castle 1993; Copeland 1992; Copeland 1998; Kua 1992). The incidence rate of DSM‐III‐R‐defined schizophrenia with first onset after 44 years is reported to be 12.6 per 100,000 population per year (Copeland 1998).

Description of the intervention

Neuroleptics remain the most effective treatment for schizophrenia, but their use in elderly people with psychosis is based on clinical data extrapolated from studies of these agents in younger populations (Devanand 1998; Frenchman 1997; Katz 1999). An extremely limited body of published studies suggests that the benefits of neuroleptics may extend to elderly people with late‐life schizophrenia (Jeste 1993). Elderly people with chronic schizophrenia have been shown to benefit from typical neuroleptics such as acetophenazine, trifluoperazine, haloperidol, fluphenazine and thioridazine (Branchey 1978; Honigfeld 1965; Tsuang 1971). The newer atypical antipsychotics are thought to be well tolerated, since they have less potential for producing extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesias (Jeste 1996; Jeste 1998; Jeste 1999; Jeste 1999a). The atypical antipsychotics do have some side effects of their own; clozapine has a high risk of spontaneous white blood cell decline (agranulocytosis), olanzapine causes significant weight gain (Duggan 2001) and possibly induces diabetes (Koro 2002; Wirshing 1998). Risperidone can also cause significant weight gain (Allison 1999), and movement disorders (Gilbody 2002; Kennedy 2001). In addition, neuroleptics do not produce complete remission of all the symptoms of schizophrenia in most patients. In one series of people with late‐onset schizophrenia, 24% did not show any signs of improvement after typical antipsychotic treatment (Pearlson 1989). Another series found that, after a minimum of three months of typical antipsychotic treatment, about 42% of people with late‐onset schizophrenia‐like psychosis showed no response, 31% of people partially improved, and 27% had remission of their symptoms (Howard 1992a). The foremost barriers to the widespread use of atypical antipsychotic medications in older adults are (1) the lack of well‐designed and well‐conducted studies to demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of these medications in older patients with multiple medical conditions, and (2) the higher cost of these medications relative to typical neuroleptics (Thomas 1998).

How the intervention might work

Neuroleptic drugs are generally thought to work through blocking certain neurotransmitter receptors in the brain. The ability of typical neuroleptics to diminish psychotic symptoms was shown to be initiated by blockade of dopamine D2 receptors in defined areas of the brain (Creese 1976; Davis 1991; Meltzer 1976). Atypical neuroleptics cause potent serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine, 5‐HT) receptor subtype 5‐HT2A relative to DA D2 receptor blockade (Arndt 1998; Meltzer 1989), with the exception of aripiprazole, a partial dopamine agonist (Lawler 1999), and amisulpride, a selective D2/D3 antagonist (Di Giovanni 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

The elderly population is expected to grow substantially worldwide. The number of people over 65 increased from about 17 million in 1900 to 342 million in 1992, and is expected to increase to 2.5 billion (20% of the total population) by 2050 (Olshansky 1993). The aging of the general population will be associated with ever elevated numbers of elderly people with late‐onset schizophrenia; the annual incidence of schizophrenia‐like psychosis in people over the age of 60 increases by 11% with each five‐year increase in age (Van Os 1995). Accordingly, the treatment of late‐onset schizophrenia is gaining increased importance, and a review of the effects of neuroleptics on people with late‐onset schizophrenia is particularly important for at least two reasons. First, pharmacotherapy in the older patient is complicated by alterations in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses; small doses of neuroleptics are usually sufficient for improvement in older patients, and particular side effects might prove dangerous (Lohr 1992). Second, most published studies do not distinguish between people with late‐onset schizophrenia and elderly people with early‐onset schizophrenia despite studies showing that the inclusion of late‐onset schizophrenia into the diagnosis of early‐onset schizophrenia or delusional disorder has poor empirical and theoretical bases (Almeida 1995). Compared with early‐onset schizophrenia, late‐onset schizophrenia shows a two to 10 times higher prevalence in women than in men (Harris 1988), has a different genetic risk (Howard 1997), has a different symptom profile, (DeLisi 1992; Howard 1993a) and has a better prognosis (Castle 1991; Harris 1988). People with late‐onset schizophrenia seem to respond differently to treatment in comparison with people with an earlier onset of illness (Jeste 1995; Jeste 1997; Jeste 1998; Lohr 1997)

Objectives

To review the beneficial and harmful effects of antipsychotic drugs for elderly people with late‐onset schizophrenia‐like psychosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. Where trials were described as 'double‐blind' and it was implied that the studies were randomised, we planned to include these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we would have included them in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we planned to use only clearly randomised trials and the results of the sensitivity analysis described in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

Elderly people (at least 80% of whom should be over 65 years of age) with a recent (within five years) diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia like illness such as delusional disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform psychosis or paraphrenia.

Types of interventions

Any typical or atypical antipsychotic drug, at any dose and mode or pattern of administration, compared to placebo, no intervention or to any other typical or atypical antipsychotic drug, at any dose and mode or pattern of administration. For the purposes of the planned sensitivity analyses outlined below, we defined low doses as follows; amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine (< 50 mg/day), iloperidone (< 4 mg/day), olanzapine (< 5 mg/day), quetiapine (< 50 mg/day), risperidone (< 2 mg/day) , sulpiride, ziprasidone (< 40mg/day), zotepine (< 100 mg/day).

Types of outcome measures

The patient‐oriented outcome measures that are important for this review are mortality (suicide or natural causes), global clinical response as defined by each included study, quality of life, adverse events, cost and service utilisation ( hospital admission, number of days in hospital). As schizophrenia is often a life‐long illness, and antipsychotic drugs are used as an ongoing treatment, we grouped outcomes according to time periods into acute (less than six weeks), short‐term (less than three months), medium‐term (three to six months) and long‐term outcomes (more than 6 months).

Primary outcomes

1. Suicide

2. Hospital admission

3. Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

4. Clinically significant response in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

5. Leaving the study early

Secondary outcomes

1. Death due to natural causes

2. Service utilisation as measured by the number of days in hospital

3. Average score/change in global state

4. Mental state

4.1 Average score/change in mental state 4.2 Clinically significant response in positive symptoms‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 Average score/change in positive symptoms 4.4 Clinically significant response on negative symptoms‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.5 Average score/change in negative symptoms

5. Behaviour

5.1 Clinically significant response in behaviour ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.2 Average score/change in behaviour

6. Extrapyramidal side effects

6.1 Incidence use of antiparkinson drugs 6.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 6.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects

7. Other adverse effects, general and specific

7.1 Number of patients leaving the study early due to adverse effects 7.2 Cardiac effects 7.3 Anticholinergic effects 7.4 Antihistamine effects 7.5 Prolactin related symptoms

8. Social functioning

8.1 Clinically significant response in social functioning ‐ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Average score/change in social functioning

9. Economic outcomes

10. Quality of life

10.1 Quality of life/ satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers 10.2 Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 10.3 Average score/change in quality of life/satisfaction

11. Cognitive functioning

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (January 2010)

We searched the register using the phrase:

[((old* or * old * in title) or (*elderly* or *paraphrenia* or *late onset* in title, abstract, and index terms or title) or ((aged* in index terms) terms of REFERENCE) or (elderly in participants of STUDY))].

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

For previous electronic searches for earlier versions of this review, please see Appendix 1.

2. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (January 2013)

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (9th Janurary 2013) using the phrase

[(* old * in title) or (*older adult* or *elderly* or *paraphrenia* or *late onset* in title, abstract, and index terms of REFERENCE) or (*older adults* in participants of STUDY))].

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings (see group module).

Searching other resources

Please see Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

For previous data and collection methods, please see Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

In order to ensure reliable selection, two review authors, AE and GA independently inspected all study citations identified by the searches and obtained full reports of the studies of agreed relevance. Where disputes arose, we resolved disagreements by discussion or, if doubt remained, by acquiring the full article for more detailed scrutiny. If doubt still remained, we added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment pending acquisition of further information and we contacted the authors of studies. For details of previous author contributions in study selection see Acknowledgements.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction

We extracted data from included trials onto standard, simple forms. The review author GA extracted data from the included study, helped by Mohannad Othman, and this was inspected by AE. We discussed disagreements, documented our decisions and, if necessary, contacted the authors of studies for clarification. When uncertainty persisted, we allocated the trial to Studies awaiting classification while we contacted the authors.

Summary of findings table

If usable data were available, we planned to use the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008 and used GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager) to create a 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Working independently, AE and GA assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. Accordingly, we categorised the risk of bias in every study into low, high or unclear risk of bias. We did not include studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias or where allocation was clearly not concealed. If disputes arose as to which category a trial has to be allocated, again, we resolved this by discussion.

Earlier versions of this review used a different, less well‐developed, means of categorising risk of bias (see Appendix 3).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous (binary) data:

For binary (yes/no) outcomes, we planned to calculate a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). If heterogeneity had been found, we would have used a random‐effects model.

Continuous data:

We included continuous data from rating scales in this review only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal and the instrument was either a self‐report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). Where possible, we made efforts to convert continuous outcome measures to binary data by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly. Otherwise, endpoint data would have been presented and if both endpoint and change data had been available for the same outcomes, only the former would have been reported in this review. We planned to estimate mean difference (MD) between groups as a summary statistic for continuous data, and, if heterogeneity had been found, we would have applied a random‐effects model.

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, the following standards would have been applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or are obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale starts from a positive value the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), there is no way of telling whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. It is thus preferable to use scale end point data, which typically cannot have negative values. If end point data was not available, then we would have used change data, but these would not have been subjected to a meta‐analysis, and would have been reported in the 'Additional data' tables.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials

Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect. Otherwise, clustering would have been dealt with in this review as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008 Section 16.3).

Cross‐over design

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. This makes cross‐over trials inappropriate for unstable conditions such as schizophrenia. Accordingly, we would have only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we would have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not have reproduced these data.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to carry out an intention to treat analysis. Studies would have been excluded from this review if they reported an attrition rate higher than 50% of participants in any group. In studies with less than 50% attrition rates, people leaving early would have been considered to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of death. We would also have analysed the impact of including studies with high attrition rates in a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this latter group had resulted in a substantive change in estimate of effects of the primary outcomes, we would have presented their data separately.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We would have considered all included studies without any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. We planned to investigate statistical heterogeneity by visual inspection of graphs and by calculating the I2 statistic. The I2 test provides an estimate of the percentage of heterogeneity thought to be due to chance, and it indicates high levels of heterogeneity when it gives a result of 75% or more (Higgins 2008). We would then have re‐analysed the data using a random‐effects model to see if this made a substantial difference. If it did, and the I2 statistic fell below 75% indicating more consistent results, we would have added the studies to the main body of trials. If using the random‐effects model did not make a difference and heterogeneity remained high, data would not have been summated, but presented separately and reasons for heterogeneity investigated.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We would have tried to locate protocols of included trials. If the protocol was available, we would have compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we would have compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results. In addition, we would have attempted to use a funnel plot (included trial effect size versus included trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of publication bias.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we would have employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. However, as discussed above, we would have applied a random‐effects model if heterogeneity had been found.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

It has been proposed that elderly people may be more sensitive to neuroleptic drugs, and that the outcome may be affected by the specific diagnosis of late‐onset psychosis. Accordingly, we would have performed subgroups analyses to test these proposals.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to undertake an analysis of the primary outcomes comparing the results when completer‐only data were used with analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We would have also performed a sensitivity analysis to compare between low‐quality and high‐quality studies. A third sensitivity analysis would have compared between acute, short‐term, medium‐term and long‐term (as defined above) randomised controlled trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Groups trials register for the initial version of this review resulted in 119 references. Of the 38 studies identified, 37 were excluded and one study added to Ongoing studies (Lacro 2001). The current updated search resulted in 211 references, from which we identified 88 studies, 81 excluded studies, one included study, one additional ongoing study and five awaiting classification.

Included studies

The original version of this review included no studies. We have included one study in the current update (Huang 2007). The characteristics of this study were as follows (Please also see Characteristics of included studies).

1. Length of study

Eight weeks.

2. Setting

Hospital inpatient.

3. Participants

3.1 Diagnosis

People with schizophrenia diagnosed according to CCMD‐3 (Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (third revision)).

3.2 Age

People with a mean age of 64.3 ± 3.2 years for the risperidone group and a mean age of 63.3 ± 3.9 years for the olanzapine group.

3.3 Sex

Twelve male and 10 female patients in the risperidone group and 11 male and 11 female patients in the olanzapine group.

3.4 History

Participants in the risperidone group had been ill for 1.6 ± 1.1 (mean ± SD) years. Participants in the olanzapine group had been ill for 1.8 ± 1.4 (mean ± SD) years.

4. Study size:

The number of people randomised was 44.

5. Interventions

5.1 Risperidone at a fixed dose of 4.1 ± 2.1 (mean ± SD) mg/day.

5.2 Olanzapine at a fixed dose of 10.2 ± 5.9 mg/day.

6. Leaving the study early

All participants completed the eight‐week study.

7. Outcomes

7.1 General remarks

All measures were obtained at baseline, four and eight weeks following the intervention.

7.2 Outcome Scales

No scales provided usable data.

7.3 Missing Outcomes

Missing outcomes were social functioning, economic outcomes, quality of life and cognitive functioning.

Excluded studies

The original version of this review excluded 37 trials, largely because they did not include or report specifically on people with late‐onset schizophrenia. Four randomised controlled trials involved people with schizophrenia, and included a minority who suffered from paraphrenia (Seager 1955; Svestka 1972; Svestka 1973; Svestka 1987). These studies, however, did not report outcomes specifically for people with paraphrenia. Phanjoo 1990 did focus on the evaluation of antipsychotics for people with late‐onset schizophrenia but the two treatments under evaluation, remoxipride and thioridazine, have both been withdrawn from global use. Thioridazine is still available, but remoxipride was last produced by AstraZeneca in 1999.

In the current update, we excluded 81studies. Four studies were not trials (Li 2002; Linden 2001; Shen 2001; Wang 2002), and four trials were not randomised (Chen 2003a; Fleischhacker 2003; Lin 2002; Wang 2005). 35 trials were excluded because the intervention was not neuroleptic medication (Bartels 2005; Bjorndal 1980; Blum 1984; Burns 2007; Chen 2003b; Delapena 2005; Depla 2003; Drake 1993; Dunn 2002; Dunn 2006; Gerlach 1977; Granholm 2004; Granholm 2005; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2008; Inouye 2003; Isley 2003; Leutwyler 2009; Mazeh 2006; McKibbin 2006; McQuaid 2001; Naoki 2003; Ogunmefun 2009; Patterson 2003; Patterson 2005; Patterson 2006; Prat 2009; Pratt 2005; Pratt 2008; Shin 2004; Twamley 2005; Twamley 2008; Wang R 2002; Zisook 2002 ). Another 34 trials were excluded because they did not involve elderly people or involved elderly people with chronic psychoses but not of late‐onset (Anon 2005; Anon 2008a; Anon 2008b; Barak 2002; Brecher 1998; CATIE 2003; Crosthwaite 2000; Docherty 2002; Glorioso 2005; Harrigan 2004; Harvey 2003; Hay 2004; Jeste 2005; Kinon 2000; Kinon 2003; Kopala 2003; Lapolla 1969; Marcelli 2002; Mintzer 2004; Myers 2002; Nordentoft 1999; Pfizer 2006; Ritchie 1999; Sikich 2002; Sun Hui 2008; Tollefson 1997; Tran 1997; Tzimos 2007; Vaglum 2002; Wang LiLi 2008; Wang XiaoQuan 2008; Yamashita 2005; Yang 2002; Yu AiZhen 2008). Four studies of late‐onset schizophrenia were excluded because of flawed sequence generation (Cheng 2007; Lin 2005; Lin 2006; Liu 2007).

Ongoing studies

The original version of this review contained a study that may be ongoing (Lacro 2001). However, the limited description of participants acquired by the reviewers did not suggest that late‐onset schizophrenia was a focus of this work. The current update identified a study that did not seem to have started yet (Barnes 2002).

Studies awaiting classification

This review contains five studies from the 2010 search that need further assessment. In order to clarify the age of the participants and the age of onset of schizophrenia, we have been unable to obtain the full text of one study (Möller 2005) and the authors of two other studies have not responded to our e‐mail enquiries (Riedel 2009; Ritchie 2003). The sequence generation of two Chinese studies of late‐onset schizophrenia was not clear (Chu 2006; Zhe 2007); the authors could not be contacted by phone and they are yet to respond to our email enquiries. From the 2013 search 48 new studies were identified and are now also in awaiting assessment.

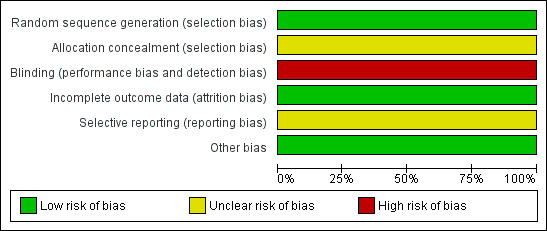

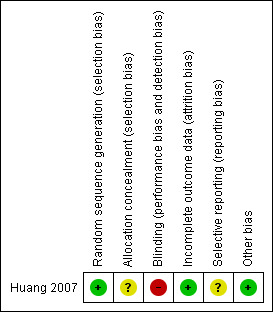

Risk of bias in included studies

Only one study fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this review (Huang 2007). For summary of risk of bias please see Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The only included study allocated participants according to a random number table.

Blinding

The only included study employed no blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

The only included study reported outcomes for all participants, but presented continuous data without SDs.

Selective reporting

We have not been able to obtain the protocol of the only included study, but there is no indication of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

None.

Effects of interventions

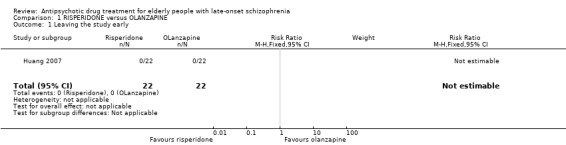

1. Leaving the study early

All participants completed the 8 week trial, indicating that both drugs were well tolerated.

2. Mental state: brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) date

The only measure of efficacy in this study was the BPRS (Overall 1962). Apparently, similar changes in BPRS scores were reported in the risperidone and the olanzapine groups (Table 1), but we were unable to use this data as they were presented without SDs.

1. Unusable outcome data due to lack of standard deviations.

| Risperidone n (male/female) 22 (12/10) |

Olanzapine n (male/female) 22 (11/11) |

|||

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| BPRS | 65.41 | 36.14 | 64.32 | 33.91 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.97 | 23.09 | 22.65 | 23.62 |

| FBS(Fasting Blood Sugar) (mmol/L) | 4.37 | 4.44 | 4.30 | 4.52 |

| Serum Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.31 | 4.37 | 4.29 | 5.10 |

| Serum Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.27 |

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale BMI: Body Mass Index FBS: Fasting Blood Sugar

3. Other outcomes

The lack of SDs also prevented us from using data related to harm, which included changes in body mass index, fasting blood glucose, serum cholesterol and serum triglycerides (Table 1).

Discussion

The search

The search for the original version of this review identified only one study that focused on the evaluation of antipsychotics for people with late‐onset schizophrenia (Phanjoo 1990). The current updated search identified seven studies clearly focused on late‐onset schizophrenia; one included study (Huang 2007), four excluded studies (Cheng 2007; Lin 2005; Lin 2006; Liu 2007) and two studies awaiting classification (Chu 2006; Zhe 2007). This observation may be the result of a newly established access to Chinese publication, but may also reflect a growing research interest in late‐onset schizophrenia and can only be welcome.

Lack of trials and unusable data

Antipsychotic drugs are perceived as beneficial for people with schizophrenia, but there are risks associated with the adverse effects (Jeste 1998; Jeste 1999). For older people the effects of these drugs may be different from the effects in younger adults (Salzman 1990). Another Cochrane review evaluated the evidence for antipsychotic drugs in elderly people with schizophrenia regardless of age of onset (Marriott 2006).This review was undertaken to examine the best available evidence on the use of antipsychotic drugs for people whose schizophrenic illness started late in life (onset after 45 years old). Late‐onset schizophrenia may be different from schizophrenia with an earlier onset in term of gender distribution, genetic risk, symptom profile, prognosis and response to treatment (see Why it is important to do this review).

It is unfortunate that the majority of the studies of antipsychotics for late‐onset schizophrenia were excluded from this review because of poor study design (quasi randomisation), and that the only included study comparing olanzapine and risperidone offered little usable data. However, these studies confirm the importance of investigating the effects of antipsychotics for late‐onset schizophrenia and demonstrate that randomised studies are possible.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

General

Pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia in late life presents some unique challenges. Conventional neuroleptic agents, have proven effective in managing the “positive symptoms” (such as delusions and hallucinations) of many older patients, but these medications have a high risk of potentially disabling and persistent side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia. Recent years have witnessed promising advances in the management of schizophrenia. Studies with mostly younger people with schizophrenia suggest that the newer “atypical” antipsychotics, such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine, may be effective in treating those patients previously unresponsive to traditional neuroleptics. Moreover, the newer medications may be more effective in treating negative symptoms and may even yield partial improvement in certain neurocognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia (Green 1997). Most of the research interest in schizophrenia has been focused on younger adults. With the ageing of the general population, there is now an increase in the attention being given to older people with schizophrenia, including those with a late onset of the disorder (Webster 1998). The literature in this area, however, is still very limited.

For clinicians

It is likely that clinicians will continue with their current practice, using clinical judgement and prescribing patterns to dictate prescribing because there is no trial‐based evidence to help guide their choice of drug. Important ethical questions are raised by current prescribing practices for people with late‐onset schizophrenia. It is difficult to know whether current practice is justified without well‐designed, well‐conducted, reported randomised studies.

For people with late‐onset schizophrenia or their relatives

It would be understandable that people with late‐onset schizophrenia or their relatives closely question their clinicians as regards the effects of antipsychotic drugs. In the light of the limited evidence, people with late‐onset schizophrenia would be justified to be disappointed in the medical/research fraternity.

For policy makers and funders

Currently policy makers have no trial‐based evidence upon which to base guidelines for late‐onset schizophrenia. They are likely to continue to rely on opinion and habit when making their recommendations. Funders of studies may wish to make this important subgroup of people a priority for future research.

Note: the 48 new citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Implications for research.

At present, there is no convincing evidence to support the use of antipsychotic medication for people with late‐onset schizophrenia. Clinically meaningful randomised studies are needed to help guide clinicians in their management of elderly people with schizophrenia. Available publications prove that studies of antipsychotic drugs for late‐onset schizophrenia are possible. There is a need for well‐designed randomised clinical trials of late‐onset psychoses, i.e., schizophrenia, delusional disorder, psychotic depression, etc. Comparisons of early‐onset and late‐onset psychoses are warranted, with meaningful outcome measures such as quality of life and activities of daily living functioning.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 January 2013 | Amended | Update search of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trial Register (see Search methods for identification of studies), 48 studies added to awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003 Review first published: Issue 2, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 October 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | As result of search in 2010, one new study added to the included studies table, most data from this study were unusable and conclusions are not altered. |

| 4 October 2011 | New search has been performed | Updated with 211 new references. |

| 4 December 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

Acknowledgements

This review was initiated by Suwanna Arunpongpaisal who wrote the protocol, undertook the search and data extraction and drafted the previous version of the review. Suchat Paholpak, Irshad Ahmed and Noorulain Aqeel helped write the protocol and the previous version of this review.

We would like to acknowledge the help of the AstraZeneca Medical Information Department who tracked down several trials of remoxipride. Many thanks to Chunbo Li for contacting Chinese authors by phone and email, and to Norah Essali for her help with RevMan. We are most grateful for the ongoing support of Claire Irving, Samantha Roberts and Lindsey Air at the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group editorial base.

We would also like to thank Mohannad Othman who helped in the 2010 search and data extraction.

The Cochrane Schizophrenia group provide a standard template for their methods section and other parts of the protocol. We have used this template and adapted it accordingly.

The additional text for the amendment following 2013 search has been added by the editorial base of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Previous searches

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Groups Trials Register (September 2002) using the phrase:

[(((elderly* or *elderly* in abstract terms or title) or (old* or * old * in title) or (*paraphrenia* or *late onset* in abstract, index terms or title) or (aged* in index terms) of REFERENCE) or (elderly in participants of STUDY))].

This register is compiled by up‐to‐date methodical searches of BIOSIS, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Dissertation abstracts, EMBASE, LILACS, MEDLINE, PSYNDEX, PsycINFO, RUSSMED, Sociofile, and is supplemented with handsearching of relevant journals and numerous conference proceedings (see Group Module).

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching We also inspected the references of all identified studies for more trials.

2. Personal contact The first author of each included study would have been contacted for information regarding unpublished trials.

3. Drug companies We contacted the manufacturers of amisulpride, or aripiprazole, or clozapine, or iloperidone, or olanzapine, or quetiapine, or risperidone, or sulpiride, or ziprasidone, or zotepine, or typical antipsychotics for additional data.

Appendix 2. Previous data collection and analysis

Dichotomous (binary) data:

For binary (yes/no) outcomes, we planned to to calculate a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). For statistically significant results, we would have calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H), and its 95% CI. If heterogeneity had been found, we would have used a random‐effects model.

Continuous data:

We intended to include continuous data from rating scales in this review only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal and the instrument was either a self report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). Where possible, we made efforts to convert continuous outcome measures to binary data by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly. Otherwise, endpoint data would have been presented and if both endpoint and change data had been available for the same outcomes, only the former would have been reported in this review. A weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups was to be estimated as a summary statistics for continuous data, and, if heterogeneity had been found, a random‐effects model would have been applied.

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, the following standards would have been applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means are reported in the paper or are obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale starts from a positive value the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), there is no way of telling whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. It is thus preferable to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values. If endpoint data were not available, then we would have used change data, but these would not have been subjected to a meta‐analysis, and would have been reported in the 'Additional data' tables.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials

Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect. Otherwise, clustering would have been dealt with in this review as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008 Section 16.3).

Cross‐over design

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. This makes cross‐over trials inappropriate for unstable conditions such as schizophrenia. Accordingly, we would have only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we would have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not have reproduced these data.

Dealing with missing data

An intention to treat analysis would have been carried out. Studies would have been excluded from this review if they reported a drop out rate higher than 50% of participants in any group. In studies with less than 50% dropout rates, people leaving early would have been considered to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of death. The impact of including studies with high attrition rates would also have been analysed in a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this latter group had resulted in a substantive change in estimate of effects of the primary outcomes, their data would have been presented separately.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We would have considered all included studies without any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity would have been investigated by visual inspection of graphs and by calculating the I2 statistics. The I2 test provides an estimate of the percentage of heterogeneity thought to be due to chance, and it indicates high levels of heterogeneity when it gives a result of 75% or more (Higgins 2008). We would then have re‐analysed data using a random‐effects model to see if this made a substantial difference. If it did, and the I2 statistics fell below 75% indicating more consistent results, we would have added the studies to the main body trials. If using the random‐effects model did not make a difference and heterogeneity remained high, data would not have been summated, but presented separately and reasons for heterogeneity investigated.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions(Higgins 2008). We would have tried to locate protocols of included trials. If the protocol was available, we would have compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we would have compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results. In addition, we would have used a funnel plot (included trial effect size versus included trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of publication bias.

Data synthesis

Where possible we would have employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. However, as discussed above, a random‐effects model would have been applied if heterogeneity had been found.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

It has been proposed that elderly people may be more sensitive to neuroleptic drugs, and that the outcome may be affected by the specific diagnosis of the late‐onset psychosis. Accordingly, we would have performed subgroup analyses to test these proposals.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to undertake an analysis of the primary outcomes comparing the results when completer‐only data were used with analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We would have also performed a sensitivity analysis to compare between low‐quality and high‐quality studies. A third sensitivity analysis would have compared between acute, short‐term, medium‐term and long‐term (as defined above) randomised controlled trials.

Appendix 3. Assessment of methodological quality

In the first version of this review, we planned to assess the methodological quality of included trials using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook (Clarke 2000) and the Jadad Scale (Jadad 1996). The former is based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect. The categories are defined below.

A. Low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment) B. Moderate risk of bias (some doubt about the results) C. High risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment)

The Jadad Scale measures a wider range of factors that impact on the quality of a trial. It includes three items. 1. Was the study described as randomised? 2. Was the study described as double‐blind? 3. Was there a description of withdrawals and dropouts?

Each item receives one point if the answer is positive. In addition, a point can be deducted if either the randomisation or the blinding/masking procedures described were inadequate. For the purpose of the analysis in this first version of the review, trials would have been included if they met the Cochrane Handbook criteria A or B. If the study did not gain at least two points on the Jadad Scale it would not have been included.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. RISPERIDONE versus OLANZAPINE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RISPERIDONE versus OLANZAPINE, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Huang 2007.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised by admission sequence. Blinding: no blinding. Duration: 8 weeks. Design: parallel. Country: China. |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (CCMD‐3).

N = 44. Age: adults over 60 years (risperidone group mean age ˜ 64.3 years (SD = 3.2), olanzapine group mean age ˜ 63 years (SD = 3.9)) ‐ check 80% value etc Sex: 23M, 21F. History: recent onset: risperidone group mean duration of illness ˜1.6 years (SD = 1.1), olanzapine group mean duration of illness 1.8 years (SD = 1.4). |

|

| Interventions | 1. Risperidone: fixed dose mean 4.1 mg/day (SD = 2.1). N = 22. 2. Olanzapine: fixed dose mean 10.2 mg/day (SD = 5.9). N = 22. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use: Mental state: BPRS: (no SD). BMI (kg/m2): (no SD). FBS (mmol/L): (no SD). Serum Cholesterol (mmol/L): (no SD). Serum Triglycerides (mmol/L): (no SD). |

|

| Notes | This study was included although we were unable to confirm that 80% of the participants were 65 or older. The age of onset, however, is clearly after the age of 60. This study provided unusable data (Table 1). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised via random number table. Chumbo Li phoned the author on 26th July, 2010. The author stated that allocation was according to random number table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No participants left the study early. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The protocol was not located, unsure if selective reporting occurred. |

| Other bias | Low risk | There was no industry funding. |

BMI: Body Mass Index BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale CCMD‐3: Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (third revision) FBS: Fasting Blood Sugar SD: standard deviation

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Anon 2005 | Participants: not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Anon 2008a | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: elderly people (mean age 70 years) with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: paliperidone. |

| Anon 2008b | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: people with early‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: risperidone and olanzapine. |

| Bamrah 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 114 elderly people with dementia and psychosis, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Barak 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 51 "geriatric inpatients with chronic schizophrenia", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Barak 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants:elderly people with chronic schizophrenia, mean age 72.7 ± 5.9 years, mean disease duration 33.1 ± 12.0 years ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: olanzapine and haloperidol. |

| Bartels 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly people with serious mental illness. Interventions: health management and supported rehabilitation. |

| Berman 1995 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 20 "geriatric patients with schizophrenia", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Bjorndal 1980 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: psychiatric patients with tardive dyskinesia. Interventions: naloxone, enkephalins, morphine. |

| Blum 1984 | Interventions: naloxone, placebo. |

| Branchey 1978 | Allocation: unclear, "double‐blind, crossover". Participants: 30 elderly inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Brecher 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: adult and elderly people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, mean age < 41 years. Interventions: risperdone and olanzepine. |

| Burns 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 59 "geriatric patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Burns 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with severe mental illness ‐ not elderly people. Interventions: supported employment (Individual Placement and Support programme) vs. vocational training. |

| Byerly 2001 | Allocation: unclear, "comparing the efficacy....". Participants: 60 people with schizophrenia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Cantillon 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 351 (in trial 1 ‐fixed dose), 296 (in trial 2 ‐titrated dose) people with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, age group not specified, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| CATIE 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: people with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. |

| Chen 2003a | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia. Interventions: olanzapine and clozapine. Age at onset: unclear. |

| Chen 2003b | Allocation: unclear. Participants: elderly people with psychotic disease. Interventions: nursing education. |

| Cheng 2007 | Allocation: not randomised ‐ according to illness severity. Participants: elderly people with first episode schizophrenia. Interventions: olanzapine vs risperdone. |

| Crosthwaite 2000 | Allocation: unclear. Participants: older patients with psychosis (age.>.50 years) ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. |

| Davidson 2000 | Allocation: unclear, "double‐blind". Participants: 180 chronic psychotic patients aged 54 to 89 years, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Delapena 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older patients with schizophrenia. Interventions: group therapy and cognitive behavioral social skills training. |

| Depla 2003 | Allocation: not randomised ‐ post test only design to assess community integration of elderly mentally ill persons. |

| Docherty 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder ‐ not late‐onset. Interventions: risperidone and olanzapine. |

| Drake 1993 | Allocation: unclear. Participants: homeless people with dual diagnosis, age range 18 to 50 years. Interventions: social network case management and intensive case management. |

| Dunn 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and elderly people with schizophrenia. Interventions: enhanced consent procedure and routine consent procedure. |

| Dunn 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and older patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Interventions: Brief Patient Education, Computer‐Assisted Instruction. Outcome: understanding of placebo control. |

| Evans 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with Alzheimer's disease and psychosis, not late‐onset psychosis. |

| Fleischhacker 2003 | Allocation: not randomised, open‐label. Participants: symptomatically stable people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Interventions: long‐acting risperidone at three different doses. |

| Gerlach 1977 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: hospitalised psychiatric patients with neuroleptic‐induced tardive dyskinesia ‐ not elderly patients. Interventions: alpha‐Methyl‐para‐tyrosine, Baclofen, Biperiden. |

| Glorioso 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and elderly patients with schizophrenia or dementia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: four atypical antipsychotic drugs. |

| Granholm 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with schizophrenia. Interventions: group cognitive‐behavioural social skills training. |

| Granholm 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and elderly people with chronic schizophrenia. Interventions: cognitive behavioural social skills training. |

| Granholm 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not aged patients. Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. |

| Granholm 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Single blind (outcome assessor). Participants: older patients with schizophrenia. Interventions:computer‐assisted cognitive behavioral social skill training, goal‐focused supportive contact. |

| Harrigan 2004 | Allocation: randomised No blinding. Participants: people with psychotic disorders, age range 18 to 65 ‐ not late‐onset. |

| Harvey 2000a | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 367 people with schizophrenia living in a community, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Harvey 2000b | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 377 people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective outpatients. Subgroup analysis for 153 elderly patients with schizophrenia, but not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Harvey 2000c | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 222 people with schizophrenia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Harvey 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 269 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Harvey 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia (mean duration of illness 36.5 years, age of onset 33 to 36 years). Interventions: risperidone and olanzapine. |

| Hay 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: acutely psychotic or agitated elderly people. Interventions: olanzapine and conventional antipsychotic drugs. |

| Hellewell 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 455 patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, age 18 to 89 years old, including only 18 elderly patients, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Howanitz 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 42 chronic schizophrenic inpatients aged 55 years or older, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Inouye 2003 | Delirium Prevention Trial. Interventions: adherence to nonpharmacologic interventions. |

| Isley 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind.

Participants: older patients with psychosis. Interventions: Medication Adherence Therapy. |

| Jeste 2001 | Allocation: randomised, Participants: 176 "geriatric" patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Jeste 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and elderly psychiatric patients ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. |

| Kinon 2000 | Allocation: randomised.

Blinding: Double blind. Method and participants: data were obtained from patients (n = 760 participants) enrollment into a large (n = 1996 not aged participants). not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Kinon 2001 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 43 "elderly dementia patients with behavioural disturbance and psychosis living in nursing homes", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Kinon 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: acutely psychotic or agitated elderly people without tardive dyskinesia ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. |

| Kopala 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Blinding: unclear. Participants: people with recent onset schizophrenia. Not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Kuntz 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 59 "geriatric" patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Lane 2001 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 24 people with first episode schizophrenia, age 18 to 45 years old, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Lapolla 1969 | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: elderly (age range 55 to 80 years) ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. Interventions: acetophenazine and thioridazine. |

| Leutwyler 2009 | Allocation: randomised. (Secondary data analysis of a lifestyle intervention programme). Participants: persons over age 40 with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Interventions: Rehabilitation Training or Usual Care plus Information. |

| Li 2002 | Design: cross‐sectional study. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia and normal adults. Outcome: assessment of cognitive functions. |

| Lin 2002 | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia. Interventions: quetiapine and perphenazine. |

| Lin 2005 | Allocation: 'randomised' by admission sequence ‐ odd for olanzapine, even for risperdone. |

| Lin 2006 | Allocation: 'randomised' by admission sequence ‐ odd for risperidone, even for perphenazine Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia. |

| Linden 2001 | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: people who had left early from a clinical trial. |

| Liu 2007 | Allocation: 'randomised' by sequence ‐ The author stated that allocation was according to odd or even numbers (phone call by Chunbo Li on 26th July, 2010). Participants: elderly people with late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: aripiprazole vs risperidone. |

| Lovett 1987 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 54 "geriatric patients with chronic brain syndrome and senile psychosis", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Marcelli 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: adolescent and young adults (age 14 to 24 years) with first acute psychotic episode. |

| Matkovits‐Gupta 1999 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia including the elderly, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Mazeh 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind, cross‐over. Participants: elderly patients with schizophrenia. Interventions: donepezil, placebos. |

| McKibbin 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizophrenic disorder and diabetes mellitus. Age: older than 40 years. Interventions: diabetes awareness and rehabilitation training vs. usual care plus information. |

| McQuaid 2001 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with schizophrenia, age 45 years and above. Interventions: Cognitive Behavioural Social Skills Training. |

| Mintzer 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 92 elderly people, 31 with schizophrenia, 22 who with schizoaffective disorder, 5 with delusional disorder, 12 with mood disorders and 12 with dementia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Mintzer 2004 | Design: post hoc analysis of a subset of older patients from and open‐label RCT. Participants: elderly people with psychosis, age 60 to 80 years ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. |

| Mohler 1970 | Allocation: non randomised, case‐control comparative study. |

| Myers 2002 | Design: RCT. Allocation: blinding ‐ double. Participants: not aged patients. |

| Naoki 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Interventions: community re‐entry programme. |

| Nordentoft 1999 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 18 to 45 years old with first time diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder. |

| Ogunmefun 2009 | Allocation: randomised. Double‐blind, cross‐over. Participants: people with tardive dyskinesia. Interventions: placebos and donepezil. |

| Patterson 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and older patients with chronic schizophrenia. Interventions: functional adaptation skills training and group therapy. |

| Patterson 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle aged and older Latino patients with psychosis. Interventions: psychosocial intervention. |

| Patterson 2006 | Allocation: randomised Participants: middle‐aged and elderly people with chronic psychotic disorders. Interventions: functional adaptation skills training. |

| Pfizer 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly people with psychosis, age > 65 years ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: asenapine. |

| Phanjoo 1990 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 18 "geriatric inpatients with schizophrenia and paranoid disorder ", 16 with late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: remoxipride versus thioridazine, remoxipride withdrawn from the market (1994), last batch produced (1999). |

| Prat 2009 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with serious mental illness. Interventions: psychosocial rehabilitation. |

| Pratt 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with serious mental illness, age 50 years and above. Interventions: the Using Medications Effectively programme. |

| Pratt 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with serious mental illness. Interventions: social rehabilitation and health care management (Helping Older People Experience Success; HOPES) vs. usual care. |

| Reams 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 59 "geriatric" patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Ritchie 1999 | Allocation: not randomised (a cohort study). Participants: elderly people on antipsychotic medications ‐ not late‐onset psychosis. Interventions: olanzapine and risperidone. |

| Salganik 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 17 "geriatric patients with chronic refractory schizophrenia", not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Salzman 2000 | Allocation: not randomised, descriptive study. |

| Seager 1955 | Allocation: unclear, "divided into two groups". Participants: 48 people including 13 with schizophrenia or paraphrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine different doses. Outcome: no data reported for subgroup of people with paraphrenia. |

| Shen 2001 | Design: cross‐sectional study. Participants: young, middle‐aged and elderly male people with schizophrenia. Outcome: serum testosterone levels. |

| Shin 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Interventions: psycho education and supportive therapy. |

| Sikich 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: children and adolescents with psychosis. Interventions: risperidone, olanzapine and haloperidol. |

| Sun Hui 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly men with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: quetiapine and risperidone. |

| Sutton 2001 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 339 people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective outpatients age 18 to 65. Subgroup analysis for 39 elderly patients(age 50 to 65) with schizophrenia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Svestka 1972 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 44 elderly women with schizophrenia including 21 with paraphrenia. Interventions: pimozide versus perphenazine. Outcome: no data reported for subgroup of women with parapharenia. |

| Svestka 1973 | Allocation: unclear "double‐blind". Participants: 46 people with schizophrenia or paraphrenia. Interventions: oxyprothepine versus perphenazine. Outcome: no data reported for subgroup of women with parapharenia. |

| Svestka 1987 | Allocation: unclear "double‐blind". Participants: 40 people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, including 9 paraphrenia. Interventions: isofloxythepine versus haloperidol. Outcomes: no data reported for subgroup of people with parapharenia. |

| Svestka 1989a | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 40 people with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, aged 17 to 67. No mention of late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Svestka 1989b | Allocation: unclear "cross‐over". Participants: 34 inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, no mention of late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Svestka 1990 | Allocation: unclear, "double‐blind". Participants: 36 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Tariot 2000 | Allocation: not randomised, open‐label trial. |

| Tollefson 1997 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: people with schizophrenia, onset of illness by the age of 45 years in 87% of the participants ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Tran 1997 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Participants: people with chronic schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, aged 18 to 65 years ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: risperidone, olanzapine. |

| Twamley 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and older people with schizophrenia. Interventions: three work rehabilitation approaches. |

| Twamley 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: middle‐aged and older people with severe mental illness. Interventions: a supported employment model (Individual Placement and Support) and conventional vocational rehabilitation. |

| Tzimos 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Double blind. Interventions: placebos and paliperidone. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia. mean age at onset of schizophrenia 34 years ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Vaglum 2002 | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: people with first episode schizophrenia, without age limit. Interventions: early detection programme. |

| Wang 2002 | Design: cross‐sectional study. Participants: people with schizophrenia taking novel or traditional antipsychotic drugs. Outcome: direct cost of treatment. |

| Wang 2005 | Allocation: not randomised. Participants: elderly people with primary‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: risperidone and perphenazine. |

| Wang LiLi 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: risperidone oral solution and risperidone tablets. |

| Wang R 2002 | Interventions: family support and psychological treatment. |

| Wang XiaoQuan 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: quetiapine and risperidone. |

| Warner 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with mental illness. Interventions: home treatment and standard care. This is only a study proposal. |

| Yamashita 2005 | Allocation: unclear. Participants: people with schizophrenia receiving conventional antipsychotic drugs. Mean age 61.4 years ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: olanzapine, perospirone, quetiapine and risperidone. Outcome: sleep quality. |

| Yamawaki 1996 | Allocation: unclear, "double‐blind". Participants: 35 elderly people with schizophrenia, not late‐onset schizophrenia. |

| Yang 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 20 to 53 years old people with schizophrenia. Interventions: nicotine patch and placebo patch. |

| Yu AiZhen 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: elderly people with schizophrenia ‐ not late‐onset schizophrenia. Interventions: olanzapine and perphenazine. |

| Zisook 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: older people with schizophrenia, age 40 years and above. Interventions: placebo vs citaloprams. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Anon 2009.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Barak 2001.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Chu 2006.

| Methods | Allocation: quasi‐randomised according to admission sequence.

Blindness: none.

Duration: 8 weeks.

Design: parallel. Country of origin: China. |

| Participants | N = 60. Diagnosis: schizophrenia (CCMD‐3). Age: 63.7 (SD = 2.1) for the quetiapine group and 64.2 (SD = 2.5) for the risperidone group. Sex (male/female): quetiapine group (16/14), risperidone group (17/13). Duration of illness: quetiapine group 4.3 months (SD = 2.2), risperidone group 4.0 months (SD = 2.3). Age at onset: older than 60 years. |

| Interventions | 1. Quetiapine: fixed dose, 200 ˜ 350mg/day. N = 30. 2. Risperidone: fixed dose, 2 ˜ 3 mg/day. N = 30. |

| Outcomes | Mental state: PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia). Adverse effects: extra pyramidal side effects, sleepiness, orthostatic hypotension, dry mouth, constipation, ECG changes, elevated alanine aminotransferase, weight gain. Leaving the study early. |

| Notes | Further details about the allocation procedure are required. Chunbo Li couldn't contact the author by telephone, and an inquiry email was sent to the author on 26th July, 2010 with no response. The outcome data of this study is presented in Table 3. |

2. Outcomes of Chu 2006.

| Quetiapine n (male/female): 30 (16/14) |

Risperidone n (male/female): 30 (17/13) |

|

| Endpoint score of PANSS (+) | 8.1 (SD = 1.7) | 8.1 (SD = 2.9) |

| Endpoint score of PANSS (‐) | 11.1 (SD = 5.1) | 10.2 (SD = 5.1) |

| General Mental state | 21.0 (SD = 6.7) | 20.1 (SD = 5.9) |

| Endpoint score of PANSS | 38.2 (SD = 11.7) | 38.1 (11.7) |

| TESS | ||

| Extra Pyramidal Symptoms | 4 | 8 |

| Sleepiness | 3 | 1 |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 3 | 1 |

| Dry mouth | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation | 1 | 0 |

| ECG changes | 4 | 3 |

| Elevated alanine aminotransferase | 1 | 0 |

| Gain weight | 0 | 2 |

| Leaving the study early | 0 | 0 |

PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Dubovsky 2010.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Dubovsky 2010a.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Dubovsky 2010b.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Dubovsky 2011.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Kircher 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Luo 2009.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

McGuire 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Mintzer 2001.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Möller 2005.

| Methods | Allocation: random, no further details. Blindness: double, no further details. Duration: 6 weeks. Design: parallel. |

| Participants | N = 36. Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐IV), schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or shared psychotic disorder. Age: 65 years or more. Sex: not described. Duration of illness: not described. Age at onset: not described. |

| Interventions | 1. Amisulpride: flexible dose. Allowed dose range: 100 to 400 mg/day. N = 24. 2. Risperidone: flexible dose. Allowed dose range: 1 to 4 mg/day. N = 12. |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early: adverse events. Cognitive functioning: MMSE (Mini Mental State Examination). Adverse effects: open interviews. Unable to use‐ Mental State: PANSS total score, BPRS total score (no usable data). Cardiac effects: (QTc), laboratory tests (no data). |

| Notes | Age at onset: Unclear ‐ requires full texts. |

NCT01625897.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |