Abstract

Background

Renal colic is a common cause of acute severe pain. Both opioids and nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended for treatment, but the relative efficacy of these drugs is uncertain.

Objectives

To examine the benefits and disadvantages of NSAIDs and opioids for the management of pain in acute renal colic.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's specialised register, the Cochrane Central Register of Randomised Controlled Trials (CENTRAL ‐ The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and handsearched reference lists of retrieved articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any opioid with any NSAID, regardless of dose or route of administration were included.

Data collection and analysis

Data was extracted and quality assessed independently by two reviewers, with differences resolved by discussion. Dichotomous outcomes are reported as risk ratio (RR) and measurements on continuous scales are reported as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals. Subgroup analysis by study quality, drug type and drug route have been performed where possible to explore reasons for heterogeneity.

Main results

Twenty trials from nine countries with a total of 1613 participants were identified. Both NSAIDs and opioids lead to clinically significant falls in patient‐reported pain scores. Due to unexplained heterogeneity these results could not be pooled although 10/13 studies reported lower pain scores in patients receiving NSAIDs. Patients treated with NSAIDs were significantly less likely to require rescue medication (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.93, P = 0.007), though most of these trials used pethidine. The majority of trials showed a higher incidence of adverse events in patients treated with opioids, but there was significant heterogeneity between studies so the results could not be pooled. There was significantly less vomiting in patients treated with NSAIDs (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.53, P < 0.00001). In particular, patients receiving pethidine had a much higher rate of vomiting compared with patients receiving NSAIDs. Gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment were not reported.

Authors' conclusions

Both NSAIDs and opioids can provide effective analgesia in acute renal colic. Opioids are associated with a higher incidence of adverse events, particularly vomiting. Given the high rate of vomiting associated with the use of opioids, particularly pethidine, and the greater likelihood of requiring further analgesia, we recommend that if an opioid is to be used it should not be pethidine.

Plain language summary

Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and opioids can significantly relieve the pain in acute renal colic, but opioids (especially pethidine) cause more adverse effects

Acute renal colic occurs when mineral or organic solids pass though the urinary tract and obstruct the urinary flow. It causes a sudden onset of severe pain, which radiates from the flank to the groin and requires immediate treatment with pain‐killers. It can also cause nausea, vomiting, hypertension and blood in the urine. Opioids and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to reduce the pain. The review found that both NSAIDs and opioids significantly reduce the pain. People experienced more adverse effects, such as vomiting, when using opioids (particularly pethidine) than when using NSAIDs.

Background

Renal colic is most commonly caused by the passage of urinary tract calculi. It has an annual incidence of approximately 16/10,000 people and a life time incidence of 2‐5% (Drach 1992; Stewart 1988). Classically, renal colic is characterised by the sudden onset of severe pain radiating from the flank to the groin. The pain is often described as the worst pain the patient has ever experienced and may be associated with nausea, vomiting, hypertension and haematuria.

The pain of renal colic is due to obstruction of urinary flow with subsequent increasing wall tension in the urinary tract. Rising renal pelvic pressure stimulates local synthesis and release of prostaglandins, and subsequent vasodilatation induces a diuresis, which further increases intrarenal pressure. Prostaglandins also act directly on the ureter to induce smooth muscle spasm.

As the majority of renal calculi will pass spontaneously, the focus of acute management should be rapid pain relief, confirmation of the diagnosis and recognition of complications requiring immediate intervention (Holdgate 1999). Both nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids have been shown to provide pain relief in acute renal colic (Curry 1995; Smally 1997). Opioids have the advantages of low cost, titratability, potency and familiarity; however there are concerns regarding opiate dependency, drug seeking behaviour presenting as renal colic. Opioids do not directly act on the cause of pain and require parenteral administration, which may limit their usefulness (Reich 1997). NSAIDs have the theoretical benefit of acting directly on the main cause of pain (prostaglandin release) and have been shown to be effective. However they are generally not titratable, have a well recognised side effect profile (including renal failure and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding), and may be less immediate and potent in their action compared with opioids. NSAIDs can be given by a variety of routes but there is some evidence that in renal colic the intravenous (IV) route provides more rapid pain relief than oral or rectal administration (Tramer 1998). A meta‐analysis of NSAIDs in renal colic in 1994 suggested that NSAIDs were at least as effective as opioids in acute renal colic (Labreque 1994). However this study did not specifically examine the difference in efficacy between NSAIDs and opioids, and did not clearly define pain relief, although it was the major outcome measured. For both opioids and NSAIDs, the 'optimal' dose for adequate analgesia is unknown.

Currently, standard Emergency Medicine texts recommend opioids and NSAIDs in the treatment of acute renal colic, both alone and in combination with each other (Cameron 2000; Tintinalli 1999). The choice of agent is generally based on clinician preference, personal experience and institutional culture.Two studies have examining the combined effect of opioids and and NSAIDs have given conflicting results and there is currently no evidence that NSIADs reduce the amount of opioid required for pain control (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Cordell 1996).

Objectives

The aim of this review was to examine the benefits and disadvantages of NSAIDs and opioids, and if possible to determine which of these drug types is most appropriate for the management of pain in acute renal colic. All clinically important outcomes including degree of pain relief, efficacy of pain relief, rate of pain recurrence and treatment side effects were explored.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs comparing any NSAID versus any opioid.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

All adult patients (>16 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute renal colic (pain less than 12 hours duration) and moderate to severe pain.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with contraindications to either NSAIDs or narcotics will be excluded.

Types of interventions

All interventions that directly compare NSAIDs versus opioids in any dose, by any route (oral, intramuscular (IM), IV, rectal, subcutaneous (SC)) and in any setting were be eligible for inclusion. Combination therapies which include an opioid or NSAID were included. NSAIDs included aspirin and COX‐2 inhibitors but not paracetamol or dipyrone. Dipyrone was excluded as it is banned in several countries (USA, UK, Australia) due to the associated risk of blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis. The efficacy of dipyrone in renal colic has been reviewed in an earlier Cochrane review (Edwards 2002).

Types of outcome measures

Studies which reported any one of the following were eligible for inclusion:

Patient‐rated pain as measured by a validated pain scale including visual analogue scales, simple descriptive scales, pain relief scales and verbal rating scales AND/OR time to pain relief AND/OR need for rescue medication AND/OR rate of pain recurrence AND/OR Adverse event rates (number of patients with one or more adverse events)

Major adverse events were defined as GI haemorrhage, renal failure, hypotension, and respiratory depression.

Minor adverse events were defined as GI disturbance without bleeding (vomiting, diarrhoea, pain), dizziness, sleepiness.

Search methods for identification of studies

Initial search

Relevant trials were obtained from the following sources (see Additional Table 2‐ Electronic search strategies)

1. Electronic search strategies.

| Database searched | Search terms |

| CENTRAL | #1 Kidney Diseases explode MeSH #2 Ureteral Diseases explode MeSH #3 Colic explode MeSH #4 (( #1 OR #2 ) AND #3) #5 Urinary Calculi explode MeSH #6 Ureteral Obstruction explode MeSH #7 urolithiasis* #8 (ureter* next stone*) or (ureter* next calcul*) or (ureter* next colic) #9 (kidney* next stone*) or (kidney* next calcul*) or (kidney* next colic) #10(renal* next calcul*) or (renal* next stone*) or (renal* next colic*) #11(urin* next calcul*) or (urin* next stone*) or (urin* next colic*) #12 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11) #13 Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal explode all MeSH #14 Indomethacin explode MeSH #15 Piroxicam explode MeSH #16 indomethacin* #17 piroxicam* #18 ketorolac* #19 tenoxicam* #20 aspirin* #21 salicylate* #22 apazone* #23 diclofenac* #24 diflunisal* #25 etodolac* #26 fenoprofen* #27 flurbiprofen* #28 ibuprofen* #29 ketoprofen* #30 meclofenamate* #31 nabumetone* #32 naproxen* #33 oxaprozin* #34 phenylbutazone* #35 sulindac* #36 tolmetin* #37 nsaid* #38 (non* next steroid* next antiinflammatory next agent*) #39 (non* next steroid* next anti* next inflammatory next agent*) #40 Narcotics MeSH 8024 #41 Analgesics, Opioid explode MeSH #42 Morphine explode MeSH #43 Meperidine explode MeSH #44 morphine* #45 meperidine* #46 pethidine* #47 opioid* #48 (#13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 OR #47) #49 #12 AND #48 #50 from 2005 to 2006 #51 #49 AND #50 |

| MEDLINE and pre‐MEDLINE | 1 exp Kidney Diseases/ 2 exp Ureteral Diseases/ 3 Colic/ 4 (1 or 2) and 3 5 exp Urinary Calculi/ 6 Ureteral Obstruction/ 7 urolithiasis.tw. 8 (ureter$ stone$ or ureter$ calcul$ or ureter$ colic).tw. 9 (kidney stone$ or kidney calcul$ or kidney colic).tw. 10 (renal stone$ or renal calcul$ or renal colic).tw. 11 (urin$ stone$ or urin$ calcul$).tw. 12 (urin$ tract stone$ or urin$ tract calcul$).tw. 13 or/4‐12 14 exp Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/ 15 exp indomethacin/ 16 piroxicam/ 17 indomethacin.tw. 18 piroxicam.tw. 19 ketorolac.tw. 20 tenoxicam.tw. 21 aspirin.tw. 22 salicylate.tw. 23 apazone.tw. 24 diclofenac.tw. 25 diflunisal.tw. 26 etodolac.tw. 27 fenoprofen.tw. 28 flurbiprofen.tw. 29 ibuprofen.tw. 30 ketoprofen.tw. 31 meclofenamate.tw. 32 nabumetone.tw. 33 naproxen.tw. 34 oxaprozin.tw. 35 phenylbutazone.tw. 36 sulindac.tw. 37 tolmetin.tw. 38 NSAID$.tw. 39 non steroid$ antiinflammatory agent$.tw. 40 non steroid$ anti inflammatory agent$.tw. 41 exp NARCOTICS/ 42 exp analgesics, opioid/ 43 exp morphine/ 44 meperidine/ 45 morphine.tw. 46 meperidine.tw. 47 pethidine.tw. 48 opioid$.tw. 49 or/14‐48 50 13 and 49 |

1. Cochrane Renal Group specialised register of randomised controlled trials

2. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL ‐ issue 2, 2003 in The Cochrane Library) for any "New" records not yet incorporated in the specialised register

3. MEDLINE and Pre MEDLINE (1966 to 31 January 2003) were searched using the above terms, combined with the optimally sensitive strategy for the identification of RCTs (Dickersin 1994) (see Cochrane Renal Group Module).

4. EMBASE (1980 to 31 January 2003) was searched using terms similar to those used for MEDLINE and combined with a search strategy for the identification of RCTs (Lefebvre 1996).

5. Reference lists of nephrology textbooks, review articles and relevant trials.

6. Conference proceeding's abstracts from nephrology scientific meetings.

7. Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials to investigators known to be involved in previous trials.

Review update

The Cochrane Renal Group's specialised register (April 2006) and CENTRAL (Issue 2, 2006) were searched. CENTRAL and the Renal Group's specialised register contain the handsearched results of conference proceedings from general and speciality meetings. This is an ongoing activity across the Cochrane Collaboration and is both retrospective and prospective (http://www.cochrane.us/masterlist.asp). Please refer to The Cochrane Renal Review Group's Module in The Cochrane Library for the complete list of nephrology conference proceedings searched.

Data collection and analysis

Included and excluded studies

This review was undertaken by two reviewers (AH and TP). Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy described were screened independently by AH and TP. All potentially relevant reviews were retained and the full text of these studies examined to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. Data extraction was carried out independently by the same reviewers using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in languages other than those familiar to the authors were translated and evaluated in the presence of a native speaker of the language. Where more than one publication of one trial existed, only the publication with the most complete data was included. Where important data was not reported, we attempted to contact the original authors to get the necessary information. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Study quality

The quality of studies to be included was assessed independently by AH and TP without blinding to authorship or journal, using the checklist developed for the Cochrane Renal Group (Renal Group 2003). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The quality items assessed were allocation concealment, intention‐to‐treat analysis, completeness to follow‐up and blinding of investigators, participants, outcome assessors and data analysis.

Quality checklist

Allocation concealment

Adequate (A): Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study

Unclear (B): Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available

Inadequate (C): Method of randomisation used such as alternate medical record numbers or unsealed envelopes; any information in the study that indicated that investigators or participants could influence intervention group

Blinding

Investigators: Yes/no/not stated

Participants: Yes/no/not stated

Outcome assessor/s: Yes/no/not stated

Data analysis: Yes/no/not stated

The above are considered not blinded if the treatment group can be identified in >20% of participants because of the side effects of treatment.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Yes: Specifically reported by authors that intention‐to‐treat analysis was undertaken and this was confirmed on study assessment.

Yes: Not stated but confirmed upon study assessment.

No: Not reported and lack of intention‐to‐treat analysis confirmed on study assessment. (Patients who were randomised were not included in the analysis because they did not receive the study intervention, they withdrew from the study or were not included because of protocol violation).

No: Stated but not confirmed upon study assessment.

Completeness of follow‐up

Per cent of participants excluded or lost to follow‐up.

Statistical assessment

Dichotomous outcomes (need for rescue medication, rate of pain recurrence, adverse event rate) results are expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Data was be pooled using the random effects model but the fixed effects model was also analysed to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers. Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (patient‐rated pain scores, time to pain relief), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales were used. Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi squared test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with a p of 0.05 used for statistical significance.

Analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants, treatments and study quality). Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age, stone size/site, and drug route/dose and where possible these subgroups were explored. Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to prior agent(s) used and the agent, dose and duration of therapy. Where possible, the risk difference (RD) with 95% CI will be calculated for adverse effects.

Where sufficient RCTs were identified, an attempt was made to examine for publication bias using a funnel plot (Egger 1997).

Results

Description of studies

The initial literature search identified 74 potentially relevant studies. Of these, 49 trials were excluded on abstract review because they were not RCTs or did not compare NSAIDS and opioids. Twenty‐five articles were retrieved for more detailed evaluation, of which a further five were excluded because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. Of these five studies, two did not have either an opioid or NSAID treatment arm ( Broggini 1985; Slade 1967), one was an uncontrolled trial (Flannigan 1983), one was not restricted to patients with renal colic (Khalifa 1986) and one gave no relevant outcome measures (Daljord 1983).Thus 20 trials were available for inclusion in the review (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Arnau 1991; Cordell 1994; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Hetherington 1986; Indudhara 1990; Jonsson 1987; Larkin 1999; Lehtonen 1983; Lundstam 1982; Marthak 1991; Oosterlinck 1990; Persson 1985; Quilez 1984; Sandhu 1994; Sommer 1989; Thompson 1989; Torralba 1999; Uden 1983). Many of the included trials did not report variance data or outcomes in a form suitable for meta‐analysis. We attempted to contact the authors of all these trials but were unable to gain any further information. Six studies had treatment arms in addition to NSAIDs and opioids, mostly antispasmodics or dipyrone (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Arnau 1991; Indudhara 1990; Lehtonen 1983; Quilez 1984; Marthak 1991). Only data for the opioid and NSAIDs groups were analysed for these six trials. Two studies used a crossover design where the alternative study drug was administered if inadequate analgesia was achieved with the first drug. As the time between drugs was short and did not allow drug washout, we included only data from the pre‐crossover phase of the trial (Cordell 1994; Jonsson 1987). One study included a third treatment arm with combination opioids and NSAIDS, data from this treatment arm was not included (Cordell 1996).

The 20 trials were conducted in nine countries, included 1613 participants and published between 1982 and 1999. The majority of studies included only those participants with renal calculi confirmed on subsequent testing using a variety of techniques, and specifically excluded patients with a clinical diagnosis which was not subsequently confirmed. Amongst the trials, five different nonsteroidal agents and seven different opioids were used, though each trial used only one type of NSAID and opioid. All but two trials (Larkin 1999; Torralba 1999) used fixed doses of both NSAIDs and opioids, regardless of patient weight. NSAIDs and opioids were administered by the parenteral route (IV or IM) in all but three trials (Cordell 1994; Indudhara 1990; Thompson 1989). In these three trials, NSAIDs were administered orally or rectally, while opioids were given parenterally.

No trial reported time to pain relief though a number reported the proportion of patients with complete pain relief within a fixed time period. We therefore used this proportion as an alternative outcome measure. No trials reported rates of pain recurrence or specifically reported serious adverse events such as renal dysfunction or gastrointestinal bleeding.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation concealment

Five trials described a randomisation method which gave adequate allocation concealment (Cordell 1994; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Jonsson 1987; Larkin 1999), the remaining trials did not give enough information to determine whether allocation concealment was adequate.

Blinding

In five studies investigators, participants and outcome assessors were all blinded (Cordell 1994; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Jonsson 1987; Larkin 1999). Participants were blinded in a further three studies ( Hetherington 1986; Sandhu 1994; Sommer 1989), not blinded in three (Indudhara 1990; Thompson 1989; Uden 1983) and in the remaining nine it was not stated. Outcome assessors were blinded in 11 studies (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Arnau 1991; Cordell 1994; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Hetherington 1986; Jonsson 1987; Larkin 1999; Lehtonen 1983; Oosterlinck 1990; Uden 1983) and it was unclear in the remaining nine whether they were blinded.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Only three studies performed analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis in participants with a clinical diagnosis of renal colic (Persson 1985; Sandhu 1994; Cordell 1996). Nine trials included only those patients with renal calculus subsequently confirmed on further testing, regardless of the initial clinical diagnosis (Lundstam 1982; Hetherington 1986; Jonsson 1987; Sommer 1989; Thompson 1989; Oosterlinck 1990; Cordell 1994; Curry 1995; Larkin 1999). The remaining trials did not clearly state whether intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. No trials reported results for both patients with a clinical and a confirmed diagnosis of renal calculus.

Completeness of follow‐up

Four studies reported completeness to follow‐up, though all four studies did not perform intention‐to‐treat analysis and the patients excluded predominantly comprised of those in whom the diagnosis was not confirmed (Curry 1995; Larkin 1999; Oosterlinck 1990; Sommer 1989). The majority of remaining trials implied that there was complete follow‐up of all included patients, though this was not overtly stated.

Effects of interventions

As the results from random and fixed effects models did not differ, only results from the random effects model are reported.

Patient rated pain scores

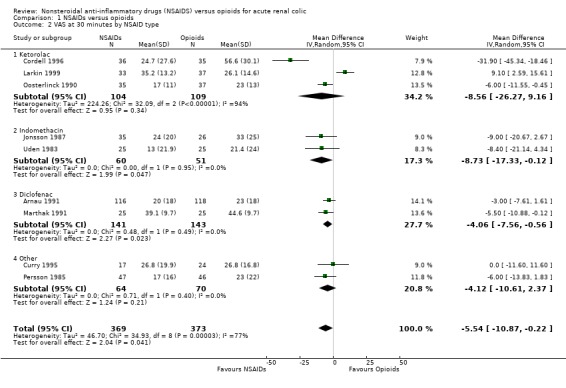

Pain scores at enrolment and at a fixed period after study drug administration was measured in 15 trials. In two trials, this outcome was measured but not reported in their results (Hetherington 1986; Indudhara 1990). Four trials reported data which could not be included in our meta‐analysis either because no variance was given (Torralba 1999), or change in pain score rather than final pain score was reported (Sandhu 1994; Sommer 1989; Thompson 1989). All but one of these four trials (Sommer 1989) demonstrated a greater reduction in pain scores in the NSAID group than in the opioid group. Nine trials reported pain on a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at various time intervals after study drug administration. Most of these trials recorded VAS at 30 minutes (Arnau 1991; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Marthak 1991; Persson 1985; Uden 1983), though two trials gave VAS scores at 20 minutes (Jonsson 1987; Larkin 1999) and one at 60 minutes (Oosterlinck 1990). Five of these trials (Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Jonsson 1987; Persson 1985; Uden 1983) reported VAS with variance, in the other four trials variance was imputed from variance measures at time zero or variance for the difference in VAS between time zero and the next measured time. However the imputed variance for these four trials was substantially smaller than the actual variance in the other five trials making the reliability of these estimates uncertain. There was significant heterogeneity between these nine studies (P < 0.001), and within the two subgroups of actual and imputed variance. Seven of the nine trials favoured treatment with NSAIDS (Arnau 1991; Cordell 1996; Jonsson 1987; Marthak 1991; Oosterlinck 1990; Persson 1985; Uden 1983), one showed no difference (Curry 1995) and one showed lower pain scores in patients treated with opioids (Larkin 1999). Subgroup analysis by NSAID type demonstrated heterogeneity for studies using ketorolac (P < 0.001), but homogeneity amongst all other trials using any other type of NSAID. There is no obvious biological or clinical explanation for this heterogeneity amongst the ketorolac trials. Combined analysis of the six trials not using ketorolac (analysis 19) showed the VAS was, on average, 4.6 mm (95% CI 1.7 to 7.5) lower in patients receiving NSAIDs compared with those receiving opioids (P = 0.002). Subgroup analysis by type of opioid did not explain heterogeneity. Route of drug administration (IV versus IM) resulted in the same subgroups as for actual and estimated variance, with the four studies reporting variance using the IV route while the five trials with imputed variance used the IM route.

Overall, of the 13 trials with reported results, 10 found lower pain scores in patients treated with NSAIDs, two demonstrated no difference and only one study found lower pain scores in patients treated with opioids.

Failure to achieve complete pain relief

Nine trials (647 participants) reported the proportion of patients who failed to achieve complete pain relief within a fixed time period after study drug administration. Eight reported this outcome at 30 minutes (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Marthak 1991; Persson 1985; Quilez 1984; Sommer 1989; Thompson 1989; Uden 1983), while one reported at 60 minutes (Oosterlinck 1990). No study found a significant difference in the proportion of patients with complete pain relief and there was no significant heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.25). Combined analysis of all nine studies showed a trend towards a higher rate of complete pain relief in patients treated with NSAIDs, but this finding was not significant (Analysis 1.4: RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.03; P = 0.11). Subgroup analysis by NSAID or opioid type did not show significant benefit for any one drug.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 4 Failure of complete pain relief at 30 minutes or next earliest.

Need for rescue analgesia

The need for rescue analgesia within four hours of administration of study drug was reported in nine trials with 806 participants (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Arnau 1991; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Hetherington 1986; Larkin 1999; Lehtonen 1983; Thompson 1989; Torralba 1999; Uden 1983). One study reported 'rescue' analgesia at 24 hours and was not included in analysis (Sandhu 1994). The decision to use rescue analgesia was generally determined by clinician preference in all trials, and the decision to give further analgesia had no objective criteria in eight of the nine studies. In four trials, pethidine was given if the physician felt the patient required further analgesia 30 minutes after study drug administration (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Arnau 1991; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995). In the remaining trials the additional analgesia was given 30 to 60 minutes after the study drug and the 'rescue' drug was either not specified, a second dose of the same study drug or the alternate study drug. In the pooled analysis, patients receiving NSAIDs were significantly less likely to require rescue medication than those receiving narcotics (Analysis 1.6: RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.93; P = 0.007). There was no statistical evidence of heterogeneity between these trials (P = 0.53). Subgroup analysis of only those trials with blinding of investigators and participants continued to show in favour of NSAIDs. All but one of the pooled trials (Uden 1983) used pethidine as the opiate, with dose ranges from 50‐150 mg. Overall, 18.9% of patients required further analgesia after a single dose of NSAID compared with 25.4% after a single dose of opioid.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 6 Rescue analgesia required.

Adverse effects

The definition of adverse effects varied between trials, and many trials included any complaint recorded on general questioning after study drug administration. No trial specifically defined or reported serious adverse events such as GI haemorrhage or renal impairment. Most trials had a short period of follow‐up (maximum 24 hours, Sandhu 1994) and none actively sought for evidence of GI bleeding or renal impairment. All studies included reporting of adverse events, but in several studies it was not possible to distinguish whether multiple events had occurred in one patient . All but four trials (Arnau 1991; Cordell 1994; Quilez 1984; Thompson 1989) reported total number of patients reporting any adverse event, rather than total number of adverse events. The majority of these 16 trials showed a higher incidence of adverse events in patients treated with opioids, but there was significant heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.01) so the results could not be pooled. Subgroup analysis by type of opioid (pethidine versus others), route of opioid administration (IV versus IM) and type of NSAID did not explain this heterogeneity. This heterogeneity may be explained by the ad hoc nature of reporting adverse events in most trials. Subgroup analysis by study quality demonstrated no heterogeneity in the four studies with blinded assessors and participants and showed a significantly higher adverse event rate in patients treated with opioids (Analysis 1.11.1: RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.93; P = 0.01). Studies without assessor and participant blinding continued to show significant heterogeneity.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 11 Adverse events by study quality.

Vomiting was reported as a specific adverse event in 10 trials (826 participants), with no evidence of heterogeneity (P = 0.58). In the pooled analysis, there was a significantly less vomiting in patients treated with NSAIDs (Analysis 1.13: RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.53; P < 0.00001). The overall rate of vomiting in patients treated with NSAIDs was 5.8%, compared to 19.5% in patients receiving opioids. Subgroup analysis by type of narcotic demonstrated that the risk of vomiting was particularly dominant in patients receiving pethidine (Analysis 1.18.1: RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.49; P < 0.00001), whereas for patients receiving non‐pethidine opioids there was no significant difference between patients receiving NSAIDs and opioids (Analysis 1.18.2: RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.24; P = 0.15). However, there were considerably more patients in trials in which pethidine was used (509 participants) than in trials using other opioids (317 participants) which may, in part, account for the lack of statistical significance in the latter group. The dose range of pethidine was 50 to 150 mg between studies, but adverse event rates did not vary according to dosage.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 13 Vomiting as adverse event.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 18 Vomiting as adverse event by opioid type.

Other subgroup analyses

There was insufficient data to perform subgroup analysis by participant age, gender, stone size or stone site for all outcomes. As all opioids and all but three NSAIDs were administered parenterally it was not possible to analyse the effect of different routes of administration other than intravenous and intramuscular. Dose ranges for individual NSAIDs varied from study to study, and due to small numbers of studies for any one NSAID, subgroup analysis by NSAID dose was not undertaken. Similarly while pethidine was the most common opioid used, with dose ranges varying from 50‐150 mg, subgroup analysis by pethidine dose within each outcome was limited by small study numbers.

Funnel plots

Insufficient trials were available to perform funnel plot analysis.

Discussion

Our review aimed to assess the relative efficacy of NSAIDs and opioids in patients presenting with a clinical diagnosis of acute renal colic. The trials included in this analysis involved a number of different NSAIDs and opioids which represent common treatment patterns internationally. However, the fact that most studies only included patients who had renal calculi confirmed on subsequent testing may limit the applicability of our findings to patients who present with a clinical picture of renal colic.

We examined the relatively analgesic efficacy through three outcomes; pain scores at a specified time after study drug administration, proportion of patients who achieved complete pain relief within a fixed time period and the need for rescue analgesia. Both opioids and NSAIDs demonstrated a clinically important analgesic effect, with a marked reduction in pain scores over time. Significant heterogeneity between studies did not allow pooled analysis of pain scores, but qualitatively the majority of studies demonstrated a lower pain scores for patients treated with NSAIDs compared with those receiving opioids, though the differences were small. In the subgroup of patients receiving NSAIDs other than ketorolac, where pooled analysis was performed, there was a statistically significant reduction in pain scores of 4.6 mm. However, this difference in scores is unlikely to be clinically significant as previous studies have shown the minimum clinically significant difference in VAS to be in the order of 9‐13 mm (Gallagher 2001; Todd 1996).

There was no significant difference between NSAIDs and opioids in the proportion of patients who achieved complete pain relief in a short time frame. The results varied widely between studies with some showing almost all patients achieving complete pain relief , while others found that less than half of patients had achieved complete pain relief. This may reflect the wide range of agents, doses and routes of administration for the study drug, though this could not be demonstrated in subgroup analysis due to the small number of studies. Given that the majority of studies did not administer the study drugs intravenously, it is not surprising that many patients had not achieved complete pain relief within 30 minutes of receiving the study drug due to slow absorption times.

Although both NSAIDs and opioids lead to clinically significant analgesia, a greater number of patients who received opioids required an additional dose of 'rescue' analgesia within an hour of study drug administration. As 9/10 trials pooled for this analysis used pethidine as their opioid, this finding may not be generalisable to all opioids. The lack of clear objective guidelines for the administration of a rescue drug may also limit interpretation of this finding, though subgroup analysis showed that even in blinded trials a higher proportion of patients receiving opioids required rescue pain relief.

Overall, both NSAIDs and opioids provided some level of analgesia though patients receiving NSAIDs achieved a slightly greater reduction in pain and were less likely to require further pain relief. However, all the included trials used fixed doses of opioids, rather than titration of opioids to an appropriate level of pain relief. Standard practice in most Emergency Departments is to titrate opioids to effect rather than give single large boluses, and this limits the applicability of our findings to every day practice (Cameron 2000). The wide variety of drug types and doses used in the studies reviewed make it difficult to identify appropriate dosing regimes for clinical practice.

Adverse events were generally higher in patients receiving opioids, however the ad hoc nature of reporting these events makes interpretation of this finding difficult. The specific adverse event of vomiting showed a clear association with opioids, in particular pethidine. Although no studies reported serious adverse events, the short follow‐up period and failure to specifically record renal dysfunction and GI bleeding means these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Single bolus doses of both NSAIDs and opioids provide pain relief to patients with acute renal colic. However, patients receiving NSAIDs achieve greater reduction in pain scores and are less likely to require further analgesia in the short term. Opioids are associated with a higher rate of vomiting than NSAIDs and this is particularly true for pethidine. Given these findings, when a single bolus of analgesia is used we recommend an NSAID rather than an opioid If opioids are to be used either because of contraindications to NSAIDS or ease of titratibility, we recommend that it should not be pethidine given the high rate of associated vomiting.

Implications for research.

No studies have examined the relative efficacy of titrated opioids rather than single bolus opioids. There are few published trials examining the potential synergistic effect of NSAIDs and opioids, and further work in this area would be helpful in determining the optimal treatment regime.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. NSAIDs versus opioids.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 VAS at 30 minutes by variance measure | 9 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 True variance given | 5 | 316 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.51 [‐19.89, ‐1.12] |

| 1.2 Variance estimated from other data | 4 | 426 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.58 [‐7.67, 4.51] |

| 2 VAS at 30 minutes by NSAID type | 9 | 742 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.54 [‐10.87, ‐0.22] |

| 2.1 Ketorolac | 3 | 213 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.56 [‐26.27, 9.16] |

| 2.2 Indomethacin | 2 | 111 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.73 [‐17.33, ‐0.12] |

| 2.3 Diclofenac | 2 | 284 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.06 [‐7.56, ‐0.56] |

| 2.4 Other | 2 | 134 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.12 [‐10.61, 2.37] |

| 3 VAS at 30 minutes pethidine or not | 9 | 742 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.54 [‐10.87, ‐0.22] |

| 3.1 Pethidine | 6 | 538 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.93 [‐12.05, 2.19] |

| 3.2 Non‐pethidine | 3 | 204 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.24 [‐13.03, ‐1.44] |

| 3.3 Other | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Failure of complete pain relief at 30 minutes or next earliest | 9 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.74, 1.03] |

| 5 Failure of complete relief by NSAID type | 9 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.74, 1.03] |

| 5.1 Diclofenac | 4 | 202 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.54, 1.87] |

| 5.2 Ketorolac | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.16] |

| 5.3 Indomethacin | 3 | 274 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.59, 1.03] |

| 5.4 Indoprofen | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.62, 1.16] |

| 6 Rescue analgesia required | 10 | 854 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.61, 0.93] |

| 7 Rescue analgesia required by study quality | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Blinded assessors and participants | 3 | 182 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.58, 0.94] |

| 7.2 Assessors and participants not blinded | 7 | 672 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.44, 1.30] |

| 8 Number of patients with adverse events | 16 | 1232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.43, 0.76] |

| 9 Number of patients with adverse events by type of opioid | 16 | 1232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.43, 0.76] |

| 9.1 Pethidine | 10 | 857 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.38, 0.74] |

| 9.2 Other opioids | 6 | 375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.35, 1.09] |

| 10 Number of patients with adverse events by NSAID type | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Indomethacin | 4 | 335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.42, 1.36] |

| 10.2 Diclofenac | 4 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.28, 1.09] |

| 10.3 Ketorolac | 5 | 468 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.47, 0.76] |

| 10.4 Other | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.02, 0.54] |

| 11 Adverse events by study quality | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Blinded assessors and participants | 4 | 243 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.57, 0.93] |

| 11.2 Assessors and participants not blinded | 12 | 989 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.34, 0.74] |

| 12 Adverse events by opioid route | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 IV | 6 | 447 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.49, 0.95] |

| 12.2 IM | 10 | 785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.31, 0.74] |

| 13 Vomiting as adverse event | 10 | 826 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.23, 0.53] |

| 14 VAS at 30 minutes by route | 9 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 IM | 4 | 426 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.58 [‐7.67, 4.51] |

| 14.2 IV | 5 | 316 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.51 [‐19.89, ‐1.12] |

| 15 Failure of complete pain relief by route | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 IM | 4 | 304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.75, 1.21] |

| 15.2 IV | 4 | 361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.66, 0.99] |

| 16 Rescue analgesia required by route | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 IM | 4 | 410 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.54, 1.19] |

| 16.2 IV | 4 | 345 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.58, 0.96] |

| 17 Failure of complete pain relief by opioid type | 9 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.74, 1.03] |

| 17.1 Pethidine | 5 | 423 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.71, 1.13] |

| 17.2 Non‐pethidine opioid | 4 | 251 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.63, 1.15] |

| 18 Vomiting as adverse event by opioid type | 10 | 826 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.23, 0.53] |

| 18.1 Pethidine | 5 | 509 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.18, 0.49] |

| 18.2 Non‐pethidine | 5 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.23, 1.24] |

| 19 VAS at 30 minutes by NSAID type (excluding ketorolac) | 6 | 529 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐7.50, ‐1.70] |

| 19.1 Indomethacin | 2 | 111 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.73 [‐17.33, ‐0.12] |

| 19.2 Diclofenac | 2 | 284 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.06 [‐7.56, ‐0.56] |

| 19.3 Other | 2 | 134 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.12 [‐10.61, 2.37] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 1 VAS at 30 minutes by variance measure.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 2 VAS at 30 minutes by NSAID type.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 3 VAS at 30 minutes pethidine or not.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 5 Failure of complete relief by NSAID type.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 7 Rescue analgesia required by study quality.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 8 Number of patients with adverse events.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 9 Number of patients with adverse events by type of opioid.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 10 Number of patients with adverse events by NSAID type.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 12 Adverse events by opioid route.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 14 VAS at 30 minutes by route.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 15 Failure of complete pain relief by route.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 16 Rescue analgesia required by route.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 17 Failure of complete pain relief by opioid type.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus opioids, Outcome 19 VAS at 30 minutes by NSAID type (excluding ketorolac).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

al‐Sahlawi 1996.

| Methods | Country: Kuwait ‐ Emergency Department Randomisation method: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING Investigators: Not stated Participants Not stated | |

| Participants | 20‐60 years Group 1: 50 (34M) Group 2: 50 (37M) Inclusion criteria: diagnosis by combined clinical and radiological Exclusion criteria: prior treatment, allergy to trial drugs, peptic ulcer disease, asthma, pregnancy, lactation | |

| Interventions | Group 1: Indomethacin 100 mg IV Group 2: pethidine 100 mg lysine‐acetyl salicylate 1.8 g IV | |

| Outcomes | Complete relief at 30 min Need for rescue analgesia at 30 min Adverse events | |

| Notes | 3rd group excluded from analysis because of drug type (acetyl salicylate) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Arnau 1991.

| Methods | Country: Spain ‐ 13 Emergency Departments Randomisation method: Not stated Power analysis: performed BLINDING Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | 18‐65 yrs Group 1: 116 (63M) Mean age 40.7 yrs Group 2: 118 (61M) Mean age 41.4 yrs Inclusion criteria: diagnosis by clinical +/‐ plain xray. Exclusions: allergy to trial drug, peptic ulcer, GI bleed, mild pain, pregnancy, lactation, prior treatment | |

| Interventions | Group 1: Diclofenac 75mg IM Group 2: pethidine 100 mg IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Need for rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | 2 groups (217 pts) not included becasue fo drug type (dipyrone) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cordell 1994.

| Methods | Country: USA ‐ Emergency Department Randomisation: computer generated table Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING Investigators: Y Participants: Y | |

| Participants | 18‐75 yrs Group 1 : 31 (18M) Mean age 39.2 yrs Group 2: 20 (18M) Mean age 38.9 yrs Method of diagnosis: confirmed by IVP, extraction or stone passage Exclusions: pregnancy, peptic ulcer, bleeding disorder, anticoagulation therapy, rectal bleeding/proctitis, allergy to trial drug, recent analgesics | |

| Interventions | Group 1: Indomethacin 100 mg PR Group 2: 5‐10mg morphine IV | |

| Outcomes | Adverse events | |

| Notes | Crossover trial, at cross over patients given drug from alternate arm, post‐crossover data not included Patient relief VAS rather than pain score VAS measured, therefore not included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cordell 1996.

| Methods | Country: USA ‐ Four emergency departments Randomisation: computer generated block Power analysis: performed BLINDING: Investigators: Y Participants: Y | |

| Participants | 18 y or older Group 1: 35 (28M), Mean age 42.0 Group 2: 36 (30M), Mean age 38.8 Inclusion criteria: diagnosis confirmed by IVP, US, stone passage or extraction Exclusion criteria: allergy to study drug, peptic ulcer disease, bleeding disorder, anticoagulation, pregnancy, renal insufficiency, suspected drug seeking behaviour | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 50 mg meperidine IV Group 2: 60 mg ketorolac IV | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Need for rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | 3rd group (35) not included because combination therapy with NSAID and opioid ITT analysis not performed on efficacy outcomes | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Curry 1995.

| Methods | Country: NZ ‐ Emergency Department Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Y Participants: Y | |

| Participants | 18‐75 y Overall 41 participants, 75% male, mean age 40 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis on IVP Exclusion criteria: allergy to study drug, contraindications to either drug, suspected drug seeking behaviour | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 40 mg tenoxicam IV Group 2: 75 mg pethidine IV | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Adverse events Need for rescue analgesia | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hetherington 1986.

| Methods | Country: UK ‐ Emergency department Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: N Participants: Y | |

| Participants | No age limits, presumed adult Overall 58 participants, 41 male, mean age 46 y Group 1: 28 Group 2: 30 Inclusion criteria: diagnosis on IVP Exclusion criteria: prior NSAIDs, allergy to trial drugs, asthma, peptic ulcer,renal insufficiency, prior analgesics | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 100 mg pethidine IM Group 2: 75 mg diclofenac IM | |

| Outcomes | Need for rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Indudhara 1990.

| Methods | Country: India ‐ Emergency department Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: No | |

| Participants | No age limits, presumed adult Overall 94 participants, 68 male, age range 19‐57 y Group 1: 33 Group 2: 31 Inclusion criteria; diagnosis confirmed in plain xray (71) or ultrasound (23) Exclusion criteria: likely alternative diagnosis | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 150 mg diclofenac PO Group 2: 50 mg pethidine IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain relief measured but not defined Adverse events | |

| Notes | 3rd group (30) not included because of drug type ('Baralgin' ) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jonsson 1987.

| Methods | Country: Sweden ‐ Emergency admissions Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Y Participants: Y | |

| Participants | 20‐75 y Group 1: 26 (24M), Mean age 44 y Group 2: 35 (30M), Mean age 44.5y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis: confirmed by urinalysis or IVP Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, peptic ulcer, severe cardiopulmonary disease, adverse reactions to study drugs | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 5 mg oxyconchloride + 50 mg papaverine IV Group 2: 50 mg indomethacin IV | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Adverse events | |

| Notes | Crossover trial, data from post‐crossover period not included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Larkin 1999.

| Methods | Country: USA ‐ Emergency department Randomisation: computer generated Power analysis: performed BLINDING: Investigators: Y Participants: Y | |

| Participants | Age > 17 y Group 1: 33 (26M), Mean age 45.5 y Group 2: 37 (27M), Mean age 40.7 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis confirmed on IVP or stone passage Exclusion criteria: < 50 kg, pregnancy, contraindications to trial drugs or contrast, suspect drug seeking behaviour, renal dysfunction | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 60 mg ketorolac IM Group 2: meperidine 100‐150 mg IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Need for rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lehtonen 1983.

| Methods | Country: Finland ‐ Hospital presentations Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | No age limits, presumed adult Group 1: 93 (69M), Mean age 44.6 y Group 2: 31 (26M), Mean age 39.5 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis by clinical, UA and IVP Exclusion criteria: asthma, known allergy, peptic ulcer, pregnancy, prior treatment | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 50 mg indomethacin IV Group 2: 50 mg pethidine IV | |

| Outcomes | Complete pain relief at 30 min Need for rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | 3rd study arm not included because of drug type (dipyrone) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Lundstam 1982.

| Methods | Country: Sweden ‐ 2 Emergency departments Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult. Group 1: 34 (25M), Age range 17‐69 Group 2: 32 (25M), Age range 22‐84 Inclusion criteria: diagnosis by urinalysis, IVP or stone passage Exclusion criteria: none stated | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 50 mg diclofenac IM Group 2: 1 ml 'Spasmofen' (combination of multiple narcotics) IM | |

| Outcomes | Adverse events | |

| Notes | Pain relief measured but not well defined and therefore not analysed | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Marthak 1991.

| Methods | Country: India ‐ Presenting to 3 hospitals Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | Adult patients. Group 1: 25 (17M), Mean age 36.4 y Group 2: 25 (20M), Mean age 34.0 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis confirmed UA, IVP or plain xray Exclusion criteria: peptic ulcer, severe cardiac/hepatic/renal insufficiency, trial drug allergy, asthma, pregnancy, prior treatment | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 75 mg diclofenac IM Group 2: 75 mg pethidine IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Adverse events Complete relief at 30 min | |

| Notes | 2nd study comparing diclofenac and dipyrone not included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Oosterlinck 1990.

| Methods | Country: UK and Belgium ‐ Treatment area: not stated Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | 18‐75 y, 45‐100 kg Group 1: 45 (32M), Median age 40 y Group 2: 37 (29M), Median age 40 y Group 3: 39 (29M), Median age 39 y Inclusion criteria:diagnosis by radiological evidence of stone or obstruction Exclusion criteria: allergy to study drugs, known alcohol/narcotic abuse, temp > 37.5C | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 10 mg ketorolac IM Group 2: 90 mg ketorolac IM Group 3: 100 mg pethidine IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Adverse events Complete relief at 60 min | |

| Notes | Patients from group 1 included in adverse events and % with complete pain relief analysis but not VAS analysis due to inability to combine data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Persson 1985.

| Methods | Country: Sweden ‐ Emergency Department Randomisation: computer generated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | > 20 y Group 1: 48 (35M), Mean age 47 Group 2: 46 (35M), Mean age 46 Inclusion criteria: clinical diagnosis, most confirmed on IVP Exclusion criteria:pregnancy, peptic ulcer, bleeding disorder, adverse reactions to trial drugs | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 400 mg indoprofen IV Group 2: 10 mg oxicone and 20 ng papaverine IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Complete pain relief at 30 min Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Quilez 1984.

| Methods | Country: Spain ‐ Emergency department Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult Group 1: 24 (14M), Mean age 43.7 y Group 2: 14 (8M), Mean age 44.9 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis on urinalysis, IVP or passage stone Exclusion criteria: None | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 75 mg diclofenac IM Group 2: 30 mg pentazocine IM | |

| Outcomes | Complete pain relief at 30 min Adverse events | |

| Notes | 3rd group (23 participants) given IM hyoscine, not included in analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sandhu 1994.

| Methods | Country: UK ‐ 6 hospitals, treatment area not stated Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Y | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult Group 1: 76 (59M), Mean age 45.2 y Group 2: 78 (58M), Mean age 42.1 y Inclusion criteria: clinical diagnosis of renal colic Exclusion criteria: prior analgesia, pregnancy, lactation, GI/renal/hepatic disease, asthma, bleeding disorder, drug abuse | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 30 mg ketorolac IM Group 2: 100 mg pethidine IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain score changes summed over time Rescue analgesia at 24 h Adverse events | |

| Notes | Data for pain scores not used in analysis due to format of information "Rescue analgesia" reported at 24 h and thus not included in results | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sommer 1989.

| Methods | Country: Denmark ‐ Treatment area not stated Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Y | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult Group 1: 27 (17M), Median age 54 y Group 2: 29 (22M), Median age 57 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis on IVP Exclusion criteria: none | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 3 ml 'Ketogan' IM group 2: 75 mg diclofenac IM | |

| Outcomes | Pain scores measured but not reported Complete pain relief at 30 min Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Thompson 1989.

| Methods | Country: UK ‐ Emergency department Randomisation: coin toss Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Y Participants: No | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult 58 patients, baseline data not given but described as no significant difference Inclusion criteria: diagnosis by IVP, stone passage/removal Exclusion criteria: asthma, trial drug allergy, renal/hepatic impairment, inflammatory bowel disease, prior treatment, pregnancy, lactation | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 100 mg pethidine 'injection', IV or IM not stated Group 2: 100 mg diclofenac PR | |

| Outcomes | Change in pain score but not absolute scores Complete pain relief at 30min Rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Torralba 1999.

| Methods | Country: Spain ‐ Treatment area not stated Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | No age limit, presumed adult 48 patients, no baseline comparisons given Inclusion criteria: method of diagnosis not described Exclusion criteria: allergy to trial drugs, peptic ulcer, asthma, renal/hepatic/cardiac disease, bleeding disorders | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 30 mg ketorolac IM Group 2: 1 mg/kg tramadol SCI | |

| Outcomes | Pain scores but no variance Rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Uden 1983.

| Methods | Country: Sweden ‐ Treatment area not stated Randomisation: Not stated Power analysis: Not stated BLINDING: Investigators: Not stated Participants: Not stated | |

| Participants | Age: < 75 y Group 1: 25 (20M), Mean age 41.4 y Group 2: 25 (22M), Mean age 39.8 y Inclusion criteria: diagnosis on clinical grounds with "xray in uncertain cases' Exclusion criteria: peptic ulcer, cardiac insuffiency, allergy to study drugs, asthma, pregnancy | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 50 mg indomethacin IV Group 2: 2 mg hydromorphine chloride‐atropine SCI | |

| Outcomes | Pain score VAS Complete pain relief in 30 min Rescue analgesia Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Al Walli 1998 | NSAID verus antimuscarinic |

| Altay 2003 | NSAID versus NSAID via different routes |

| Anonymous 2004 | Review article only |

| Basar 1991 | NSAID versus spasmolytic (tropenzilium) |

| Bertolotto 2003 | NSAID versus NSAID |

| Broggini 1985 | Diclofenac was compared to placebo |

| Chang 2002 | Opioid versus opioid |

| Chaudhary 1999 | Combination drug regime in both arms |

| Clayman 2002 | No NSAID arm |

| Daljord 1983 | No relevant outcome measures |

| Dellabella 2003 | Not in acute treatment of renal colic |

| Dubinsky 1997 | No NSAID or narcotic arm |

| el‐Sherif 1990 | NSAID versus spasmolytic |

| Engeler 2005 | NSAID versus NSAID |

| Eray 2002 | Opioid versus opioid |

| Ergene 2002 | NSAID versus antiemetic (non opioid) |

| Finlay 1982 | Opiod versus opioid |

| Flannigan 1983 | Uncontrolled study |

| Fraga 2003 | NSAID versus NSAID |

| Graiff 1985 | No NSAID |

| Hedenbro 1988 | No NSAID or opioid |

| Ho 2004 | NSAID versus NSAID |

| Hofstetter 1993 | GTN versus buscopan |

| Holdgate 2005 | Buscopan versus placebo |

| Hussain 2001 | Not in acute renal colic, not NSAIDs or opioids |

| Iguchi 2002 | Trigger point therapy |

| Jones 1998 | NSAID versus antimuscarinic |

| Jones 2001 | NSAID versus NSAID/antimuscarin |

| Khalifa 1986 | Not restricted to patients with renal colic |

| Lloret 1986 | Nifedipine versus multianalgesics |

| Lopes 2001 | Desmopressin |

| Muller 1990 | Metaclopramide versus opioid |

| Muriel 1993 | NSAID versus dipyrone |

| Muriel‐Villoria 1995 | Dipyrone comparison |

| Nelson 1988 | NSAID by 2 routes |

| Nissen 1990 | NSAID by 2 routes |

| Oosterlinck 1982 | Opioid versus opioid |

| Pavlik 2004 | Not NSAID versus opioid |

| Porpiglia 2004 | No opioid arm |

| Pourrat 1984 | NSAID versus NSAID/dipyrone equivalent |

| Primus 1989 | Tramadol versus metimazole |

| Resim 2005 | Alpha blocker versus placebo |

| Saita 2004 | No NSAID or opioid arm |

| Sanchez‐Carpena 2003 | NSAID versus dypirone |

| Servedio 1974 | Flavoxate |

| Slade 1967 | NSAID was not compared to opioid |

| Stankov 1994 | Dipyrone versus tramadol/buscopan |

| Stein 1996 | NSAID versus NSAID |

| Torchi 1983 | Dose response study for indoprofen |

| Tura 1986 | Ceruletide study |

| Xue 1996 | Not NSAID versus opioid |

Contributions of authors

Anna Holdgate ‐ Designing and coordinating the review, trial selection, quality assessment, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the review.

Tamara Pollock ‐ Trial selection, quality assessment, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the review.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

al‐Sahlawi 1996 {published data only}

- al‐Sahlawi KS, Tawfik OM. Comparative study of the efficacy of lysine acetylsalicylate, indomethacin and pethidine in acute renal colic. European Journal of Emergency Medicine 1996;3(3):183‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arnau 1991 {published data only}

- Arnau JM, Cami J, Garcia‐Alonso F, Laporte JR, Palop R. Comparative study of the efficacy of dipyrone, diclofenac sodium and pethidine in acute renal colic. Collaborative Group of the Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1991;40(6):543‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cordell 1994 {published data only}

- Cordell WH, Larson TA, Lingeman JE, Nelson DR, Woods JR, Burns LB, et al. Indomethacin suppositories versus intravenously titrated morphine for the treatment of ureteral colic. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1994;23(2):262‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cordell 1996 {published data only}

- Cordell WH, Wright SW, Wolfson AB, Timerding BL, Maneatis TJ, Lewis RH, et al. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac, meperidine, and both (balanced analgesia) for renal colic. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1996;28(2):151‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Curry 1995 {published data only}

- Curry C, Kelly AM. Intravenous tenoxicam for the treatment of renal colic. New Zealand Medical Journal 1995;108(1001):229‐30. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hetherington 1986 {published data only}

- Hetherington JW, Philp NH. Diclofenac sodium versus pethidine in acute renal colic. British Medical Journal Clinical Research Ed 1986;292(6515):237‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Indudhara 1990 {published data only}

- Indudhara R, Vaidyanathan S, Sankaranarayanan A. Oral diclofenac sodium in the treatment of acute renal colic. A prospective randomized study. Clinical Trials Journal 1990;27(5):295‐300. [EMBASE: 1991125957] [Google Scholar]

Jonsson 1987 {published data only}

- Jonsson PE, Olsson AM, Petersson BA, Johansson K. Intravenous indomethacin and oxycone‐papaverine in the treatment of acute renal colic. A double‐blind study. British Journal of Urology 1987;59(5):396‐400. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larkin 1999 {published data only}

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D'Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1999;17(1):6‐10. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lehtonen 1983 {published data only}

- Lehtonen T, Kellokumpu I, Permi J, Sarsila O. Intravenous indomethacin in the treatment of ureteric colic. A clinical multicentre study with pethidine and metamizol as the control preparations. Annals of Clinical Research 1983;15(5‐6):197‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lundstam 1982 {published data only}

- Lundstam SOA, Leissner KH, Wahlander LA, Kral JG. Prostaglandin‐synthetase inhibition with diclofenac sodium in treatment of renal colic: comparison with use of a narcotic analgesic. Lancet 1982;1(8281):1096‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marthak 1991 {published data only}

- Marthak KV, Gokarn AM, Rao AV, Sane SP, Mahanta RK, Sheth RD, et al. A multi‐centre comparative study of diclofenac sodium and a dipyrone/spasmolytic combination, and a single‐centre comparative study of diclofenac sodium and pethidine in renal colic patients in India. Current Medical Research & Opinion 1991;12(6):366‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oosterlinck 1990 {published data only}

- Oosterlinck W, Philp NH, Charig C, Gillies G, Hetherington JW, Lloyd J. A double‐blind single dose comparison of intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine and pethidine in the treatment of renal colic. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1990;30(4):336‐41. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Persson 1985 {published data only}

- Persson NH, Bergqvist D, Melander A, Zederfelt B. Comparison of a narcotic (oxicone) and a non‐narcotic anti‐inflammatory analgesic (indoprofen) in the treatment of renal colic. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica 1985;151(2):105‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quilez 1984 {published data only}

- Quilez C, Perez‐Mateo M, Hernandez P, Rubio I. Usefulness of a non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory, sodium diclofenac, in the treatment of renal colic. Comparative study with a spasmolytic and an opiate analgesic. Medicina Clinica 1984;82(17):754‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sandhu 1994 {published data only}

- Sandhu DP, Iacovou JW, Fletcher MS, Kaisary AV, Philip NH, Arkell DG. A comparison of intramuscular ketorolac and pethidine in the alleviation of renal colic. British Journal of Urology 1994;74(6):690‐3. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sommer 1989 {published data only}

- Sommer P, Kromann‐Andersen B, Lendorf A, Lyngdorf P, Moller P. Analgesic effect and tolerance of Voltaren and Ketogan in acute renal or ureteric colic. British Journal of Urology 1989;63(1):4‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thompson 1989 {published data only}

- Thompson JF, Pike JM, Chumas PD, Rundle JS. Rectal diclofenac compared with pethidine injection in acute renal colic. BMJ 1989;299(6708):1140‐1. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Torralba 1999 {published data only}

- Nicolas Torralba JA, Rigabert Montiel M, Banon Perez V, Valdelvira Nadal P, Perez Albacete M. Intramuscular ketorolac compared to subcutaneous tramadol in the initial emergency treatment of renal colic [Ketorolaco intramuscular frente a Tramadol subcutaneo en el tratamiento inicial de urgencia del colico renal]. Archivos Espanoles de Urologia 1999;52(5):435‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Uden 1983 {published data only}

- Uden P, Rentzhog L, Berger T. A comparative study on the analgesic effects of indomethacin and hydromorphinechloride‐atropine in acute, ureteral‐stone pain. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica 1983;149(5):497‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Al Walli 1998 {published data only}

- Al Waili NS, Saloom KY. Intravenous tenoxicam to treat acute renal colic: comparison with buscopan compositum. JPMA ‐ Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 1998;48(12):370‐2. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Altay 2003 {published data only}

- Altay B, Horansali K, Kendirci M, Tanriverdi O, Boylu U, Miroglu C. Double‐blind placebo controlled, randomized clinical trial of piroxicam FDDF and intramusculer piroxicam in the treatment of renal colic: A comperatives study. Turk Uroloji Dergisi 2003;29(4):460‐4. [EMBASE: 2004050146] [Google Scholar]

Anonymous 2004 {published data only}

- Anonymous. NSAIDs better than opioids for kidney stone pain. Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;272(7304):759. [EMBASE: 2004314461] [Google Scholar]

Basar 1991 {published data only}

- Basar I, Bircan K, Tasar C, Ergen A, Cakmak F, Remzi D. Diclofenac sodium and spasmolytic drugs in the treatment of ureteral colic: a comparative study. International Urology & Nephrology 1991;23(3):227‐30. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bertolotto 2003 {published data only}

- Bertolotto M, Quaia E, Gasparini C, Calderan L, Pozzi MR. Resistive index in patients with renal colic: differences after medical treatment with indomethacin and ketorolac. Radiologia Medica 2003;106(4):370‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Broggini 1985 {published data only}

- Broggini M, Corbetta E, Grossi E, Borghi C. Sodium diclofenac in ureteral colic. Comparative double‐blind study with placebo. Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica 1985;37(4):493‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chang 2002 {published data only}

- Chang C‐H, Wang C‐J, Yeh Y‐C, Hsu S‐J. Effectiveness of sublingual buprenorphine and intramuscular pethidine in acute renal colic. Formosan Journal of Surgery 2002;35(1):9‐11. [EMBASE: 2002095448] [Google Scholar]

Chaudhary 1999 {published data only}

- Chaudhary A, Gupta RL. Double blind, randomised, parallel, prospective, comparative, clinical evaluation of a combination of antispasmodic analgesic Diclofenac + Pitofenone + Fenpiverinium (Manyana vs Analgin + Pitofenone + Fenpiverinium (Baralgan) in biliary, ureteric and intestinal colic. Journal of the Indian Medical Association 1999;97(6):244‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clayman 2002 {published data only}

- Clayman RV. Effectiveness of nifedipine and deflazacort in the management of distal ureter stones. Journal of Urology 2002;167(2 Pt 1):797‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daljord 1983 {published data only}

- Daljord OA, Barstad S, Norenberg P. Ambulatory treatment of an acute attack in urinary calculi. A randomized study of the effects of Petidin, Fortralin, Temgesic and Confortid. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening 1983;103(12):1006‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dellabella 2003 {published data only}

- Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Efficacy of tamsulosin in the medical management of juxtavesical ureteral stones. Journal of Urology 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2202‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dubinsky 1997 {published data only}

- Dubinsky I, Penciner R. Nitroglycerin and renal colic. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1997;29(6):824‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

el‐Sherif 1990 {published data only}

- el‐Sherif AE, Foda R, Norlen LJ, Yahia H. Treatment of renal colic by prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors and avafortan (analgesic antispasmodic). British Journal of Urology 1990;66(6):602‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engeler 2005 {published data only}

- Engeler DS, Ackermann DK, Osterwalder JJ, Keel A, Schmid HP. A double‐blind, placebo controlled comparison of the morphine sparing effect of oral rofecoxib and diclofenac for acute renal colic. Journal of Urology 2005;174(3):933‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eray 2002 {published data only}

- Eray O, Cete Y, Oktay C, Karsli B, Cete N, Ersoy F. Intravenous single‐dose tramadol versus meperidine for pain relief in renal colic. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2002;19(5):368‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ergene 2002 {published data only}

- Ergene U, Pekdemir M, Canda E, Kirkali Z, Fowler J, Coskun F. Ondansetron versus diclofenac sodium in the treatment of acute ureteral colic: A double blind controlled trial. International Urology & Nephrology 2002;33(2):315‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finlay 1982 {published data only}

- Finlay IG, Scott R, McArdle CS. Prospective double‐blind comparison of buprenorphine and pethidine in ureteric colic. British Medical Journal Clinical Research Ed 1982;284(6332):1830‐1. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Flannigan 1983 {published data only}

- Flannigan GM, Clifford RP, Carver RA, Yule AG, Madden NP, Towler JM. Indomethacin ‐ an alternative to pethidine in ureteric colic. British Journal of Urology 1983;55(1):6‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fraga 2003 {published data only}

- Fraga A, Almeida M, Moreira‐Da‐Silva V, Sousa‐Marques M, Severo L, Matos‐Ferreira A, et al. Intramuscular Etofenamate versus Diclofenac in the Relief of Renal Colic: A Randomised, Single‐Blind, Comparative Study. Clinical Drug Investigation 2003;23(11):701‐6. [EMBASE: 2003454340] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graiff 1985 {published data only}

- Graiff C, Bezza M, Ziller F, Stringari B, Brentari R, Bertagnolli G, et al. Caerulein in the treatment of biliary and renal colic. Peptides 1985;6 Suppl 3:47‐51. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hedenbro 1988 {published data only}

- Hedenbro JL, Olsson AM. Metoclopramide and ureteric colic. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica 1988;154(7‐8):439‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ho 2004 {published data only}

- Ho MK, Chung CH. A prospective, randomised clinical trial comparing oral diclofenac potassium and intramuscular diclofenac sodium in acute pain relief. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine 2004;11(2):69‐77. [2004199659] [Google Scholar]

Hofstetter 1993 {published data only}

- Hofstetter AG, Kriegmair M. Treatment of ureteral colic with glycerol trinitrate. Fortschritte der Medizin 1993;111(16):286‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Holdgate 2005 {published data only}

- Holdgate A, Oh CM. Is there a role for antimuscarinics in renal colic? A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Urology 2005;174(2):572‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hussain 2001 {published data only}

- Hussain Z, Inman RD, Elves AW, Shipstone DP, Ghiblawi S, Coppinger SW. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in patients with ureteral stones: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Urology 2001;58(4):521‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iguchi 2002 {published data only}