Abstract

R-loops are abundant, RNA containing chromatin structures that form in the genomes of both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Devising methods to identify the precise genomic locations of R-loops is critical to understand how these structures regulate numerous cellular processes including replication, termination, and chromosome segregation, and how their unscheduled formation results in disease. Here, we describe a new, highly sensitive, and antibody-independent method, MapR, to profile native R-loops genome-wide. MapR takes advantage of the natural specificity of the RNase H enzyme to recognize DNA:RNA hybrids, a defining feature of R-loops, and combines it with a CUT&RUN approach to target, cleave, and release R-loops that can then be sequenced. MapR has low background, is faster than current R-loop detection technologies, and can be performed in any cell type without the need for generating stable cell lines.

Introduction

R-loops are triplex nucleic acid structures comprising a DNA-RNA hybrid and displaced ssDNA (Thomas et al., 1976). R-loops occur naturally and form either as a result of transcription or through interaction of long non-coding RNAs with DNA (Blank-Giwojna et al., 2019; Chedin, 2016; Crossley et al., 2019; Skourti-Stathaki and Proudfoot, 2014; Sun et al., 2013). At most genetic loci, transient R-loops are quickly resolved by cellular machinery to prevent detrimental effects on gene expression, genome replication and stability (Cristini et al., 2018; Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2018; Skourti-Stathaki et al., 2011; Song et al., 2017; Yasuhara et al., 2018). However, some R-loops can persist and become pathogenic as they are associated with several repeat expansion neurodegenerative disorders and other neurological disorders (Garcia-Muse and Aguilera, 2019; Groh et al., 2017; Perego et al., 2019; Yuce and West, 2013). Exactly where these R-loops form across the genome in specific disease states and their impact on gene expression programs is unclear.

Several techniques have been described previously to identify the genomic locations of R loops. The most widely used R-loop mapping techniques depend on an antibody, S9.6 (Boguslawski et al., 1986), that recognizes DNA:RNA hybrids (Dumelie and Jaffrey, 2017; Ginno et al., 2012; Nadel et al., 2015; Wahba et al., 2016). The drawbacks of using the S9.6 antibody have been widely documented (Hartono et al., 2018; Konig et al., 2017). Other methods to detect R-loops, which take advantage of the ability of a catalytically inactive form of RNase H to recognize DNA:RNA hybrids without degrading the RNA moiety, have been developed (Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2017; Ginno et al., 2012), but these methods have not been widely adopted because of their inefficiency compared to S9.6 based methods. The RNase H based method that has shown most promise in terms of sensitivity is R-ChIP, which requires the production of a stable cell line expressing a tagged version of the inactive RNase H protein (Chen et al., 2017). It has also become clear in recent years that S9.6 antibody and RNase H recognize complementary sets of R-loops (Vanoosthuyse, 2018). Therefore, to gain an overall view of R-loop locations genome-wide it becomes important to have access to efficient techniques that use both R-loop recognition strategies. With this in mind, we developed MapR, a fast, robust, and easy R-loop detection strategy that can be used in any cell type without the prior generation of stable transgenic cell lines(Yan et al., 2019).

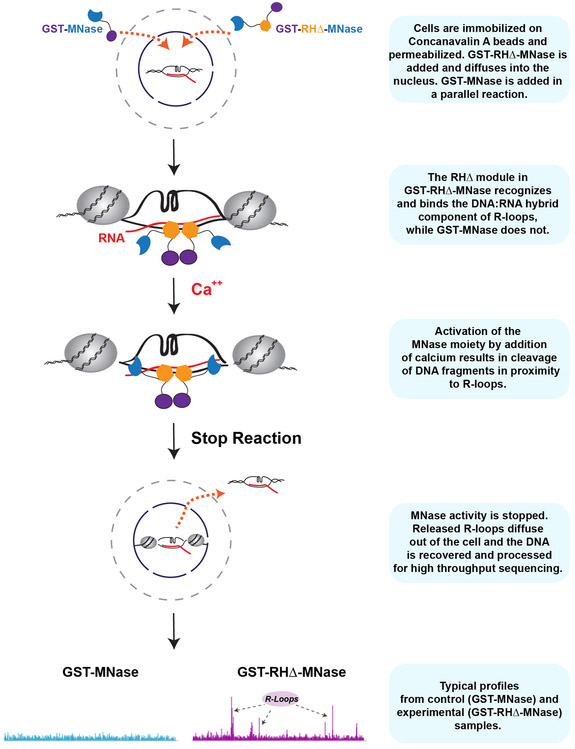

MapR experiments have a simple workflow (Figure 1). Briefly, cells are immobilized on concanavalin A coated beads and permeabilized. Equimolar amounts of a catalytically deficient mutant of RNase H fused to micrococcal nuclease (GST-RHΔ-MNase) or GST-MNase is added to immobilized cells. GST-MNase and GST-RHΔ-MNase proteins are expressed in and purified from E.coli. The RHΔ module recognizes and binds R-loops on chromatin. Controlled activation of the MNase moiety by addition of calcium results in cleavage of DNA fragments in proximity to R-loops. Released R-loops diffuse out of the cell and the DNA is recovered and sequenced. In this unit, we present a detailed step-by-step protocol and discuss other critical parameters.

Figure 1:

Schematic of MapR workflow with a brief experimental outline.

MATERIALS

E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Thermo Fisher, # C601003)

pGEX-6P-1 GST-MNase (Addgene # 136291)

pGEX-6P-1 GST- RH∆-MNase (Addgene # 136292)

Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Fisher scientific, # BP1755)

1XPBS (see recipe)

PrepEase Protein Purification Glutathione Agarose 4B (Affymetrix, # 78820)

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Elution buffer (see recipe)

Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (BIO-RAD, # 5000006)

BC100 (see recipe)

BioMag Plus Concanavalin A (Concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads; Polysciences, # 86057)

Binding buffer (see recipe)

Wash buffer (see recipe)

5% Digitonin solution (see recipe)

Dig-wash buffer (see recipe)

Spike in DNA (see recipe)

2X Stop buffer (see recipe)

NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, # E7645S)

NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Dual Index Primers Set1; NEB, # E7600S)

PROTEIN EXPRESSION

Transform BL21 E. Coli with GST-MNase and GST-RH∆-MNase expressing plasmids and grow on LB-Ampicillin agar plates overnight at 37°C.

Pick one colony and inoculate into 5 ml LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Culture in a 37°C shaker overnight.

Transfer 5 ml of overnight bacterial culture into 500 ml LB containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Incubate in a shaker at 37°C for 2-3 hrs until optical density measured at 600nm reaches 0.5-0.6.

Induce protein expression by adding IPTG (1 M stock solution) to a final concentration to 0.5 mM. Return to 37°C shaker for 3 hrs.

Spin down bacterial cultures at 8,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. At this step, bacterial cell pellets can be stored at −80°C until ready to proceed for protein purification.

PROTEIN PURIFICATION

-

6.

Resuspend bacterial pellet from 500 ml expression culture in 30 ml ice-cold PBS buffer.

-

7.

Lyse bacteria by sonication and clear the lysate by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C.

-

8.

Transfer the supernatant containing recombinant proteins to a new tube and keep on ice.

-

9.

Equilibrate GST-agarose beads by resuspending 150 μL beads in 1 ml cold PBS.

-

10.

Centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 2 min at 4°C and remove the supernatant. Repeat twice for a total of 3 bead washes in PBS.

-

11.

Add beads to cleared bacterial lysate and incubate overnight on a rotator at 4°C.

-

12.

Centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and remove the supernatant.

-

13.

Resuspend beads in 1 ml cold PBS, transfer to an Eppendorf tube and place on rotator for 5 min at 4°C.

-

14.

Centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and discard the supernatant. Repeat steps 13 and 14 for a total of 3 wash steps.

-

15.

Resuspend beads in 200 μL GST elution buffer and put on rotator for 30 min at 4°C.

-

16.

Centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and carefully remove the supernatant that contains purified recombinant proteins.

-

17.

Repeat Steps 15 and 16 four times for a total of 5 elutions.

-

18.

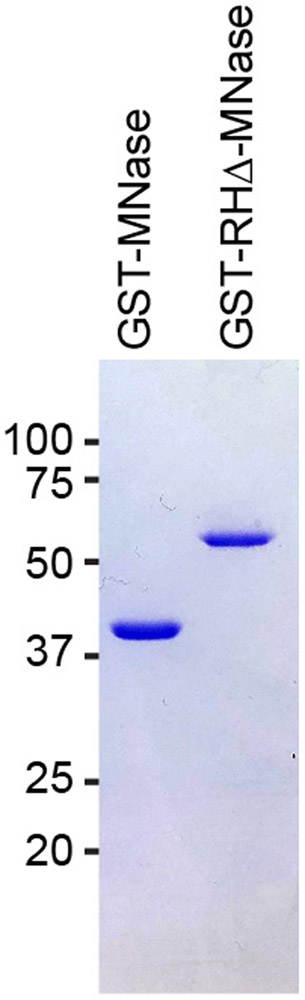

Run 5 μL of each elution on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and Coomassie stain to ascertain purity (Figure 2).

-

19.

Measure protein concentration by Bradford.

-

20.

Pool high concentration elutions and dialyze against 2 L of BC100 buffer for 2 hrs at 4°C. Transfer to 2 L of fresh BC100 buffer and dialyze for another 2 hrs.

-

21.

Centrifuge dialyzed protein samples at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Carefully collect the supernatant, add glycerol to a final concentration of 25%, and measure protein concentration. Store protein in aliquots at −80°C.

Figure 2:

Coomassie stained gel of purified recombinant GST-MNase and GST-RHΔ-MNase proteins.

HARVESTING AND IMMOBILIZING CELLS TO BEADS

NOTE- The protocol described below is for 2-5 million cells per experiment. Each experiment requires 10 μl Concanavalin A coated bead slurry. Concanavalin A beads for 4 experiments can be processed together without changes in wash buffer volumes. Cells for 4 experiments can be immobilized on beads in one tube and then split into separate tubes for each experiment.

-

22.

Add 1 ml binding buffer to wash the Concanavalin A-coated beads. Put tubes on a magnetic stand for 1 min and discard the supernatant. Repeat Step 22 for a total of 3 beads washes.

-

23.

Resuspend beads in wash buffer. Use 10 μL wash buffer per experiment i.e. if beads for 4 experiments are processed together, resuspend beads in 40 μL wash buffer.

-

24.

Trypsinize any mammalian cell type. Ensure that cells are in a single cell suspension and count cell number. Use 2-5 million cells per experiment.

-

25.

Spin down cells at 600 x g for 3 min at room temperature. Discard supernatant.

-

26.

Resuspend cell pellets by gentle pipetting in 1 ml room temperature wash buffer.

-

27.

Spin down cells at 600 x g for 3 min at room temperature. Discard supernatant. Repeat steps 26 and 27 for a total of 2 wash steps.

-

28.

Resuspend the cell pellets in 1 ml room temperature wash buffer.

-

29.

Add washed Concanavalin-A beads from Step 23. If cells from 4 experiments are processed together, add 40 μL bead slurry.

-

30.

Rotate at room temperature for 1 hr.

-

31.

Divide immobilized cells equally into new tubes, one tube per experiment, i.e. 2-5 million immobilized cells in each tube.

TARGETING PROTEINS TO DNA:RNA HYBRIDS

-

32.

Place tubes on a magnetic stand and withdraw all the liquid carefully. Discard supernatant.

-

33.

Add 50 μL of dig-wash buffer to the immobilized cells. Resuspend by pipetting gently.

-

34.

Add GST-RH∆-MNase or GST-MNase recombinant proteins to separate tubes to a final protein concentration of 1 μM and mix.

-

35.

Transfer the mixture to a new Eppendorf tube.

IMPORTANT- This step ensures that beads with immobilized cells are contained within a small volume because of surface tension and do not get dispersed along the walls of the tube.

-

36.

Rotate at 4°C overnight.

-

37.

Quick spin (100g, 15s) at room temperature to remove any liquid that has accumulated on the top and sides of the tube.

-

38.

Place tubes on magnetic stand and withdraw all the liquid carefully. Discard supernatant.

-

39.

Add 1 ml dig-wash buffer to wash the immobilized cells by pipetting gently.

-

40.

Quick spin at room temperature and place tubes on magnetic stand. Discard supernatant.

-

41.

Repeat Steps 39-40 two times for a total of 3 wash steps.

MNASE ACTIVATION TO CLEAVE NUCLEIC ACIDS

-

42.

After the last wash step, place tubes on magnetic stand and withdraw all the liquid carefully. Discard supernatant.

-

43.

Add 100 μL of dig-wash buffer to resuspend the cells bound to beads.

-

44.

Keep the tubes on wet ice for 2 min to chill down to 0°C.

-

45.

Add 2 μL of 0.1M CaCl2 to the samples and mix. Immediately return tubes to wet ice.

-

46.

Incubate the samples for 30 min at 0°C. Mix by tapping gently at the 15 min timepoint.

-

47.

Add 100 μL 2X Stop buffer and mix thoroughly to stop the reaction.

RELEASING AND COLLECTING CHROMATIN FRAGMENTS CONTAINING DNA:RNA HYBRIDS

-

48.

Incubate samples for 10 min on a 37°C heat block to release chromatin fragments.

-

49.

Spin down at 16,000 x g for 5 min at 4°C and place tubes on a magnetic stand.

-

50.

Remove the supernatant carefully and transfer to a new tube. Add 2 μL 10% SDS and 2.5 μL Proteinase K (20 mg/ml).

-

51.

Incubate samples for 10 min on a 70°C heat block.

-

52.

Spin down with a quick pulse and add 300 μL phenol chloroform isoamyl alcohol mix (Invitrogen, # 15593049). Mix thoroughly.

-

53.

Transfer samples to phase-lock gel heavy tubes (Quanta bio, # 2302830) and spin down at 16,000 x g for 5 min at room temperature.

-

54.

Transfer upper aqueous phase to a new tube and add 0.5X volume (100μL) of 7.5M NH4OAc and 4 μL of linear acrylamide (VWR, # 97063-560).

-

55.

Add 2.5X volumes (750 μL) of cold 100% ethanol. Mix thoroughly and store at −80°C for 1 hr.

-

56.

Spin down at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Discard supernatant.

-

57.

Add 1 ml 75% ethanol to the pellet and centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C.

-

58.

Discard the supernatant and air-dry for 2 min.

-

59.

Add 20 μL of TE buffer to dissolve the pellet.

-

60.

Use 7 μL DNA to make libraries and store the remaining at −20°C. DNA amount may have to be increased when using small cell numbers.

-

61.

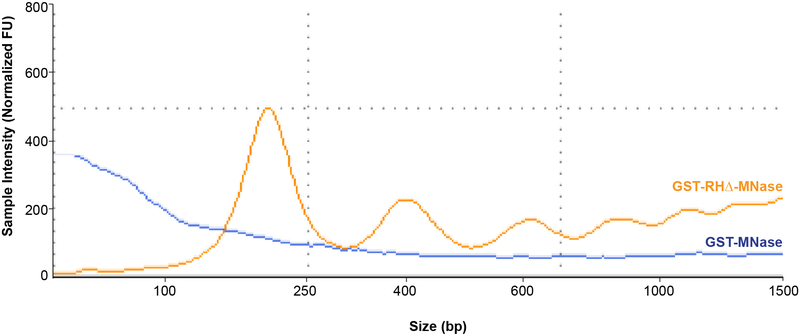

Run 1 μl on TapeStation to assess MapR experiment success. Depending on initial cell number, DNA may have to be diluted prior to loading on TapeStation.

-

62.

Proceed for library construction using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit. Follow manufacturer’s instructions for library preparation.

Reagents and Solutions

NOTE-

All buffers are autoclaved and stored at room temperature unless otherwise noted.

1XPBS:

137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4, Adjust final pH to 7.4. To prepare 1 L 1XPBS, add 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, 0.24 g KH2PO4, make up to 1 L with water and adjust pH to 7.4.

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Elution buffer:

125 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM reduced L-glutathione. To prepare 50 ml GST elution buffer, add 6.25 ml of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1.5 ml of 5M NaCl, 153.7 mg reduced L-glutathione, and make up to 50 ml with water. Filter-sterilize using a 0.22μm filter.

BC100:

50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM DTT, and 0.2 mM PMSF. To prepare 1 L BC100, add 50 ml of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 4 ml of 0.5 M EDTA pH 8.0, 7.46 g of KCl, 100 ml of Glycerol and make up to 1 L with water. Store at 4°C. Add 2 ml of 0.1 M PMSF, and 1 ml of 1 M DTT immediately before use.

5% Digitonin solution:

To prepare 2 ml of 5% digitonin solution, add 100 mg digitonin to 2 ml boiling water. Store at −20 °C. Reheat the solution to 100 °C before using.

Binding buffer:

Binding buffer contains 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MnCl2. To prepare 10 ml binding buffer, combine 200 μL of 1 M HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 100 μL of 1 M KCl, 100 μL of 0.1 M CaCl2 and 10 μL of 1 M MnCl2 and make up to 10 ml with water. Store at 4°C for up to six months.

Wash buffer:

20 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Spermidine, and 1 mM protease inhibitor. To prepare 50 ml wash buffer, add 1 ml of 1 M HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 1.5 ml of 5 M NaCl, 25 μL of 1 M Spermidine and make up to 50 ml with water. Add one tablet Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche, # 11836170001) to 50 ml wash buffer. Store at 4 °C for up to one week.

Dig-wash buffer:

To prepare 10 ml dig-wash buffer, add 40 μL 5% digitonin to 9.96 ml wash buffer. Prepare fresh each time before use.

Spike in DNA:

Spike-in DNA was extracted from Drosophila S2 cell lines and fragmented to approximately 200 bp by sonication. Any heterologous DNA can be selected dependent on the experiment. Fragmentation can also be achieved by micrococcal nuclease digestion.

2X Stop buffer:

To prepare 1 ml 2X Stop buffer, combine 68 μL of 5 M NaCl, 40 μL of 0.5 M EDTA, 20 μL of 0.2 M EGTA, 4 μL of 5% digitonin, 5 μL of 10 mg/ml RNase A, 10 μL of 5 mg/ml linear acrylamide and 2 pg/ml spike-in DNA and make up to 1 ml with water. Prepare fresh for each experiment.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

Advantages and Limitations

MapR was developed as an alternative antibody independent method to profile R-loops genome-wide and as such takes advantage of the natural specificity of RNase H to recognize DNA:RNA hybrids. It is heavily based on CUT&RUN, a new and fast method to identify transcription factor binding sites genome-wide (Skene et al., 2018; Skene and Henikoff, 2017). In CUT&RUN, targeted genomic regions are released from the nucleus by micrococcal nuclease (MNase) and sequenced directly, without the need for affinity purification, that greatly increases sensitivity, and lowers background compared to traditional chromatin immunoprecipitation. CUT&RUN also has the potential to work in small cell numbers. MapR has similar advantages to CUT&RUN, but unlike CUT&RUN it relies on the use of recombinant proteins and not antibodies. The specificity of the recombinant GST-RHΔ-MNase for DNA:RNA hybrids allows for recognition of R-loops in vivo and the use of GST-MNase in a parallel reaction assesses for non-specific genomic cleavage by MNase. Furthermore, compared to R-ChIP (Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2017), the use of exogenously added recombinant proteins in MapR ensures that R-loops can be mapped in any cell type without the need to generate stable transgenic cell lines.

The MapR protocol described here does not discriminate between the template and non-template strands and therefore cannot identify which DNA strand is involved in DNA:RNA hybrid formation. This is likely because unlike enrichment-based approaches to profile R-loops genome-wide, such as DRIP and its derivatives (Dumelie and Jaffrey, 2017; Ginno et al., 2012; Nadel et al., 2015; Wahba et al., 2016), DRIVE (Ginno et al., 2012), and R-ChIP (Chen et al., 2017), MapR (Yan et al., 2019) relies on the release and diffusion of nucleic acids from the nucleus. This property makes it challenging to separate RNA within R-loops from RNAs that diffuse out of the nucleus. However, we speculate that with a few experimental modifications, it will be possible to confer strandedness to MapR.

Critical Parameters

Enzymatic activity of recombinant proteins

Both the binding and enzymatic properties of the recombinant proteins used for MapR are critical to experimental success. After purification, it is important to confirm that GST-RH∆-MNase, but not GST-MNase, can bind DNA:RNA hybrids in vitro using Electrophoretic Mobility Shift assays (EMSA). Alternatively, other nucleic acid immunoprecipitation assays can be used and specificity of interactions assessed by real time PCR. The activity of the MNase moiety in both recombinant proteins should also be tested using chromatin digestion assays. Digestion patterns can be observed by agarose gel electrophoresis or running samples on a TapeStation. Both EMSA and MNase chromatin digestion are standard assays that have been described previously in numerous publications. To obtain the best quality datasets, recombinant proteins must be stored in aliquots for no longer than 2 months at −80°C.

Protein concentration

MapR experiments with large cell numbers (0.5-5X106) work well with a final protein concentration of 1μM. However, we have found that cell numbers under 0.1X106 show more variation in results. For experiments requiring the use of smaller cell numbers, we recommend titration of the recombinant proteins to ensure high signal-to-noise ratio between experimental (GST-RH∆-MNase) and control (GST-MNase) datasets.

Detergent concentration and temperature

Detergent concentration and temperature requirements for MapR should follow the same guidelines as CUT&RUN and have been thoroughly described previously in (Skene et al., 2018; Skene and Henikoff, 2017). Briefly, digitonin concentrations for efficient permeabilization may require optimization based on cell type and binding of cells to Concanavalin-A beads is performed at room temperature to reduce cellular stress and maintain nuclear integrity.

Understanding the Results

We have measured the amount of DNA released by Qubit or Nanodrop and found that comparison of DNA quantity obtained from GST-MNase and GST-RHΔ-MNase does not accurately demonstrate experimental success. A better predictor of success for a MapR experiment prior to high throughput sequencing is the nucleic acid fragmentation pattern observed by TapeStation or Bioanalyzer (Figure 3). We observe that GST-MNase samples do not show a clear banding pattern, while GST-RHΔ-MNase does. The reason for this may be that GST-MNase is unable to bind chromatin specifically, while GST-RHΔ-MNase is targeted to R-loops on chromatin. The controlled MNase activation limits random cleavage by soluble GST-MNase but allows for efficient chromatin cleavage by GST-RHΔ-MNase that is bound to R-loops. This observation using TapeStation may not be possible with very low cell numbers.

Figure 3:

TapeStation trace of a MapR experiment. Profiles of GST-MNase (blue) and GST-RHΔ-MNase (orange) digestion patterns are shown.

Time Considerations

The purification of recombinant proteins for MapR is simple since both proteins are abundantly expressed and are soluble. Protein expression and purification takes 2 days. In our experience, recombinant proteins purified at different times have always shown adequate MNase activity and ability to bind DNA:RNA hybrids.

MapR also has a simple and straightforward workflow and takes a total of 1.5 days once recombinant proteins are obtained. Cells are incubated with recombinant proteins on Day 1 and DNA:RNA hybrids are cleaved and released on Day 2. We have always incubated cells with recombinant proteins overnight. However, we speculate that this incubation step can be shortened to 4-6 hours to further reduce the total experimental time, which may be a requirement for primary cells or cell types that cannot withstand an overnight incubation step.

Acknowledgements

K.S. acknowledges support from the NIH New Innovator Program DP2-NS105576, and the Basser Center for BRCA at Penn Medicine.

LITERATURE CITED

- Blank-Giwojna A, Postepska-Igielska A, and Grummt I (2019). lncRNA KHPS1 Activates a Poised Enhancer by Triplex-Dependent Recruitment of Epigenomic Regulators. Cell Rep 26, 2904–2915 e2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguslawski SJ, Smith DE, Michalak MA, Mickelson KE, Yehle CO, Patterson WL, and Carrico RJ (1986). Characterization of monoclonal antibody to DNA.RNA and its application to immunodetection of hybrids. J Immunol Methods 89, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chedin F (2016). Nascent Connections: R-Loops and Chromatin Patterning. Trends Genet 32, 828–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Zhang X, Fu XD, and Chen L (2019). R-ChIP for genome-wide mapping of R-loops by using catalytically inactive RNASEH1. Nat Protoc 14, 1661–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chen JY, Zhang X, Gu Y, Xiao R, Shao C, Tang P, Qian H, Luo D, Li H, et al. (2017). R-ChIP Using Inactive RNase H Reveals Dynamic Coupling of R-loops with Transcriptional Pausing at Gene Promoters. Mol Cell 68, 745–757 e745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristini A, Groh M, Kristiansen MS, and Gromak N (2018). RNA/DNA Hybrid Interactome Identifies DXH9 as a Molecular Player in Transcriptional Termination and R-Loop-Associated DNA Damage. Cell Rep 23, 1891–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley MP, Bocek M, and Cimprich KA (2019). R-Loops as Cellular Regulators and Genomic Threats. Mol Cell 73, 398–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumelie JG, and Jaffrey SR (2017). Defining the location of promoter-associated R-loops at near-nucleotide resolution using bisDRIP-seq. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Muse T, and Aguilera A (2019). R Loops: From Physiological to Pathological Roles. Cell 179, 604–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginno PA, Lott PL, Christensen HC, Korf I, and Chedin F (2012). R-loop formation is a distinctive characteristic of unmethylated human CpG island promoters. Mol Cell 45, 814–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh M, Albulescu LO, Cristini A, and Gromak N (2017). Senataxin: Genome Guardian at the Interface of Transcription and Neurodegeneration. J Mol Biol 429, 3181–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartono SR, Malapert A, Legros P, Bernard P, Chedin F, and Vanoosthuyse V (2018). The Affinity of the S9.6 Antibody for Double-Stranded RNAs Impacts the Accurate Mapping of R-Loops in Fission Yeast. J Mol Biol 430, 272–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig F, Schubert T, and Langst G (2017). The monoclonal S9.6 antibody exhibits highly variable binding affinities towards different R-loop sequences. PLoS One 12, e0178875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J, Athanasiadou R, Lemetre C, Wijetunga NA, P OB., Sato H, Zhang Z, Jeddeloh J, Montagna C, Golden A, et al. (2015). RNA:DNA hybrids in the human genome have distinctive nucleotide characteristics, chromatin composition, and transcriptional relationships. Epigenetics Chromatin 8, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego MGL, Taiana M, Bresolin N, Comi GP, and Corti S (2019). R-Loops in Motor Neuron Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 56, 2579–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro de Almeida C, Dhir S, Dhir A, Moghaddam AE, Sattentau Q, Meinhart A, and Proudfoot NJ (2018). RNA Helicase DDX1 Converts RNA G-Quadruplex Structures into R-Loops to Promote IgH Class Switch Recombination. Mol Cell 70, 650–662 e658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene PJ, Henikoff JG, and Henikoff S (2018). Targeted in situ genome-wide profiling with high efficiency for low cell numbers. Nat Protoc 13, 1006–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene PJ, and Henikoff S (2017). An efficient targeted nuclease strategy for high-resolution mapping of DNA binding sites. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skourti-Stathaki K, and Proudfoot NJ (2014). A double-edged sword: R loops as threats to genome integrity and powerful regulators of gene expression. Genes Dev 28, 1384–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ, and Gromak N (2011). Human senataxin resolves RNA/DNA hybrids formed at transcriptional pause sites to promote Xrn2-dependent termination. Mol Cell 42, 794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Voit R, and Grummt I (2017). SIRT7 and the DEAD-box helicase DDX21 cooperate to resolve genomic R loops and safeguard genome stability. Genes Dev 31, 1370–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Csorba T, Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ, and Dean C (2013). R-loop stabilization represses antisense transcription at the Arabidopsis FLC locus. Science 340, 619–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, White RL, and Davis RW (1976). Hybridization of RNA to double-stranded DNA: formation of R-loops. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73, 2294–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoosthuyse V (2018). Strengths and Weaknesses of the Current Strategies to Map and Characterize R-Loops. Noncoding RNA 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahba L, Costantino L, Tan FJ, Zimmer A, and Koshland D (2016). S1-DRIP-seq identifies high expression and polyA tracts as major contributors to R-loop formation. Genes Dev 30, 1327–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, Shields EJ, Bonasio R, and Sarma K (2019). Mapping Native R-Loops Genome-wide Using a Targeted Nuclease Approach. Cell Rep 29, 1369–1380 e1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Kato R, Hagiwara Y, Shiotani B, Yamauchi M, Nakada S, Shibata A, and Miyagawa K (2018). Human Rad52 Promotes XPG-Mediated R-loop Processing to Initiate Transcription-Associated Homologous Recombination Repair. Cell 175, 558–570 e511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuce O, and West SC (2013). Senataxin, defective in the neurodegenerative disorder ataxia with oculomotor apraxia 2, lies at the interface of transcription and the DNA damage response. Mol Cell Biol 33, 406–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]