ABSTRACT

Human heart failure is characterized by arrhythmogenic electrical remodeling consisting mostly of ion channel downregulations. Reversing these downregulations is a logical approach to antiarrhythmic therapy, but understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of the reduced currents is crucial for finding the proper treatments. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and has been found to play pivotal roles in different diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. Recently, the UPR is reported to regulate multiple cardiac ion channels, contributing to arrhythmias in heart disease. In this review, we will discuss which UPR modulators and effectors could be involved in regulation of cardiac ion channels in heart disease, and how the understanding of these regulating mechanisms may lead to new antiarrhythmic therapeutics that lack the proarrhythmic risk of current ion channel blocking therapies.

KEYWORDS: Cardiac ion channels, chaperones, early afterdepolarizations, ER stress, long QT, oxidative stress, RNA stability, sudden cardiac death

Introduction

Heart failure and arrhythmias

The foundation of a regular heart rhythm is the cardiac action potential (AP) of cardiomyocyte. The cardiac AP relies upon highly regulated active and passive ion transport through Na+, K+, Ca2+ and other channels and transporters [1]. The cardiac Na+ channel (Nav1.5) governs phase 0 of depolarization of the AP. The K+ and Ca2+ channels determine the characteristic plateau of phase 2. K+ channels are also responsible for the phases 3 and 4 (the resting membrane potential) of the AP. Ca2+ channels and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) contribute to excitation-contraction coupling and pacemaker activities. Any disturbance of these ion channels can alter the delicate balance between depolarizing and repolarizing ionic currents, leading to slow conduction and prolongation of the AP duration (APD) that are observed in human heart failure.

Human heart failure is associated with life-threatening arrhythmias. Understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of arrhythmias is crucial for discovering safe and efficacious new therapies. Early studies show that arrhythmias occur by three fundamental mechanisms: enhanced automaticity, triggered arrhythmias, or reentry. In each case, the initiation of the arrhythmia is secondary to excess, undesirable electrical activity. Based on this concept, ion channel blocking drugs were developed to treat arrhythmias. While these drugs are partially effective, their efficacy is limited by proarrhythmic risk. In other words, these drugs can generate arrhythmias as well as prevent them. This paradox becomes more understandable if one realizes that in most cardiac pathological conditions, ion channels are downregulated already. Blocking these channels further may reduce undesirable electrical activity, but it also exacerbates the underlying electrical defect responsible for arrhythmia generation.

Changes of cardiac ion channels and transporters underlie the increased arrhythmic risk in cardiomyopathy. For many ion channels, heart failure results in downregulation of the channel current. For example, Nav1.5 protein and the macroscopic Na+ current (INa) are reduced in human heart failure and contribute to a decreased upstroke velocity (dV/dtmax) of the AP phase 0. These changes can jeopardize the impulse propagation and decrease conduction velocity in heart tissue, causing conduction disturbances and ventricular arrhythmias [2–8]. Animal model studies reveal reductions in K+ currents including the transient outward current (Ito, conducted mainly by rapidly inactivating K+ channel Kv4.3), inward rectifying current (IK1, conducted mainly by the inward rectifying K+ channel Kir2.1), and slow delayed rectifying current (IKs, conducted by slowly inactivating K+ channel KvLQT1). These reductions are responsible for prolonged APD, afterdepolarizations, heterogeneous repolarization patterns and ventricular arrhythmias [9–15]. Decreased L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL, conducted by Cav1.2) can cause repolarization delay and early and delayed afterdepolarizations (EADs and DADs). Nevertheless, the reasons for these changes remain unknown. Understanding these changes and their origins should allow for more effective therapeutic strategies free from the proarrhythmic effects, which limit the use of approved ion channel blocking drugs.

The importance of the unfolded protein response in heart function

Adult cardiomyocytes lack significant regenerative potential and require a vital balance of its contents such as sarcomeres, membrane ion channel proteins, and mitochondria to maintain viability and function throughout the life of the individual. Therefore, protein quality control is crucial for cardiomyocyte survival and function. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is one important mechanism of protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to monitor and regulate misfolded and unfolded proteins [16]. The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SER) of cardiomyocytes is not only the place where membrane proteins, such as cardiac ion channels undergo synthesis, folding, and assembling, but the SER serves also as a Ca2+ reservoir for a normal excitation-contractility coupling. Therefore, the SER of cardiomyocytes is critical not only for general cellular function but also for myocyte contractility.

Activated UPR can inhibit nascent protein synthesis to attenuate the ER stress, but this can also cause reduced expression of essential proteins, which will affect cell function and even induce cell apoptosis when the UPR activation is severe and prolonged [17,18]. The UPR has been investigated extensively in neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes but not in heart disease. In the past decade, the UPR has been found to play important roles in pathological cardiac hypertrophy [19,20], dilated cardiomyopathy [21], ischemic cardiomyopathy [22–24], diabetic heart disease [25,26], and human heart failure [6,27]. There are many excellent review articles discussing the ER stress and the heart [28], the biology of the ER stress in heart [29,30], the ER stress and ischemic heart disease [30,31], and targeting the ER stress and the UPR in cardiovascular disease [32]. Previously, we have reviewed the role of the UPR in heart disease and cardiac arrhythmias and discussed the rationale for and the challenges to target the UPR in heart disease for treatment of arrhythmias [33,34]. In this review, we will discuss which UPR modulators and effectors could be involved in regulation of cardiac ion channels in heart disease and how the understanding of these regulating mechanisms may help point out new directions for future therapeutics.

What is the UPR?

Three arms of the UPR

The UPR is highly conserved in evolution from yeast to all mammalians. It is initially an adaptive stress response and plays protective roles for cell survival by eliminating unfolded or misfolded proteins. Nevertheless, when prolonged ER stress occurs, the UPR can lead to cell apoptosis. When under ER stress, unfolded or misfolded protein accumulation triggers the dissociation of glucose regulated protein-78 (Grp78) from the three main UPR sensors, double stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring ER-to-nucleus signal kinase 1 (IRE1), and activating transcription factor-6α (ATF6α), leading to their activation.

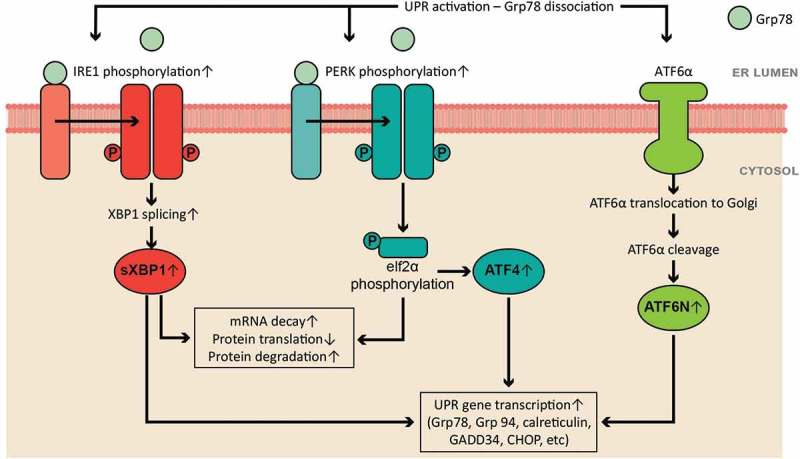

Activation of the three UPR sensors initiates three complicated signal cascades (Figure 1) to increase protein folding capacity by increasing UPR genes expression and translation (such as ER chaperone proteins Grp78, Grp94, calreticulin, and GADD34) and to reduce ER protein burden by enhancing mRNA decay, inhibiting protein translation, and accelerating protein degradation. When Grp78 dissociates, PERK and IRE1 oligomerize, become phosphorylated, and induce activation of downstream effectors: phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) splicing, respectively. Phosphorylated eIF2α inhibits ribosomal-mRNA interactions, leading to subsequent mRNA degradation and nascent protein translation reduction. Phosphorylation of eIF2α also enhances gene expression of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which increases the gene expression of ER chaperone proteins. Spliced XBP1 (sXBP1) degrades mRNA, upregulates gene expression of ER chaperones, and enhances ER-associated protein degradation. When Grp78 dissociates from ATF6α, it translocates to Golgi and is cleaved to the activated form of ATF6α, ATF6N (cleaved N-terminus of ATF6α). ATF6N translocates to the nucleus to enhance the gene expression of UPR targets such as ER chaperones. The signaling cascades of the three arms have been investigated mainly in neural degeneration diseases and diabetes mellitus [35–38], although a wide variety of cardiovascular diseases have been associated with the UPR activation, such as ischemia/reperfusion, myocardial infarction, hypertension, and heart failure [32–34,39–42].

Figure 1.

The scheme of the unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling cascades and functions.

What is known about the UPR in heart disease?

In heart disease, the ER is often under stress from oxidative stress, hypoxia, and glucose deprivation. In the past two decades, activated UPR has been reported in ischemia/reperfusion [43–46], dilated cardiomyopathy [21], myocardial infarction [23,47–49], hypertension [50–53], diabetic cardiomyopathy [25,54,55], and heart failure [6,33,51,56–58] with increased expression of ER chaperones (Grp78 and calreticulin) and effectors from all three UPR arms. For example, the PERK and IRE1 arms are activated in human failing hearts with increased mRNA and/or protein levels of Grp78, sXBP1, PERK, ATF4, and CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) [6,59]. Elevated Grp78 and CHOP are reported in mouse models of heart failure [51,60]. Our group found activated UPR in human failing heart tissue with elevated PERK, CHOP and calreticulin [6]. Elevated ATF6 protein levels occur in heart failure patients with dilated and ischemic cardiomyopathy [21].

When the ER homeostasis is disturbed, not only is the UPR is activated, Ca2+ homeostasis and protein posttranslational modifications can be altered as well. Activated UPR disturbs Ca2+ handling and increases oxidative stress and cell apoptosis, all of which have been reported to contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy [23]. SER Ca2+ ATPase isoform 2a (SERCA2a) and 3f (SERCA3f) are both altered in heart failure. SERCA3f is upregulated in human failing hearts, and overexpression of this Ca2+ pump increases XBP1 splicing and Grp78 expression [61]. This indicates that SERCA3f is likely an UPR effector and participates in the ER stress in human heart failure. PERK helps to maintain SERCA2a levels in a transaortic constriction model of heart failure, a potentially salutary effect [53].

The UPR and arrhythmias

Heart failure is characterized by arrhythmogenic electrical remodeling consisting mostly of ion channel downregulations. Activated UPR leads to suppression of nascent protein translation, which has been found to affect membrane expression of cardiac ion channels [6,62]. In human failing heart, abnormal splice variants of SCN5A encoding the α subunit of cardiac Nav1.5 are elevated and result in truncated, nonfunctional channel proteins trapped in the ER. This leads to PERK activation and causes downregulation of the full-length normal Nav1.5 protein expression, causing a dominant negative reduction in INa density and consequently decreased conduction velocity [2,6]. The effect of activated PERK is not specific to Nav1.5. UPR activation also results in a reduction of KCND3 that encodes the α subunit of Kv4.3. Kv4.3 conducts Ito, which is the main contributor to the notch of phase 1 of the cardiac AP and is responsible for early repolarization. Reduced Ito can increase membrane resistance, causing shortening of the cardiac action potential duration and phase 2 reentry [13,63]. Blocking PERK prevents these ion channel downregulations [6].

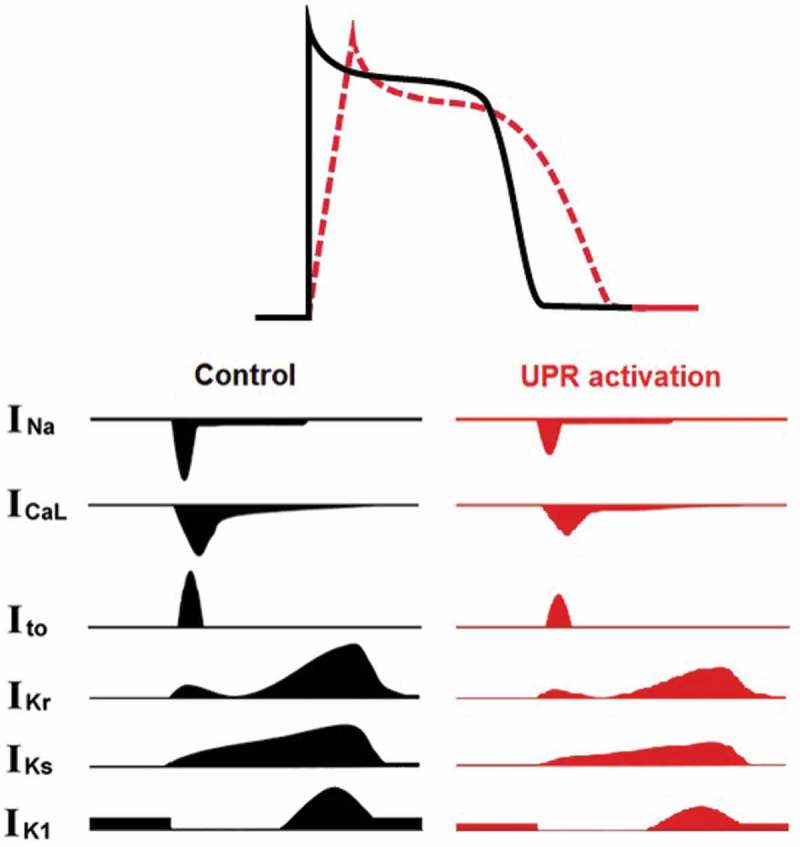

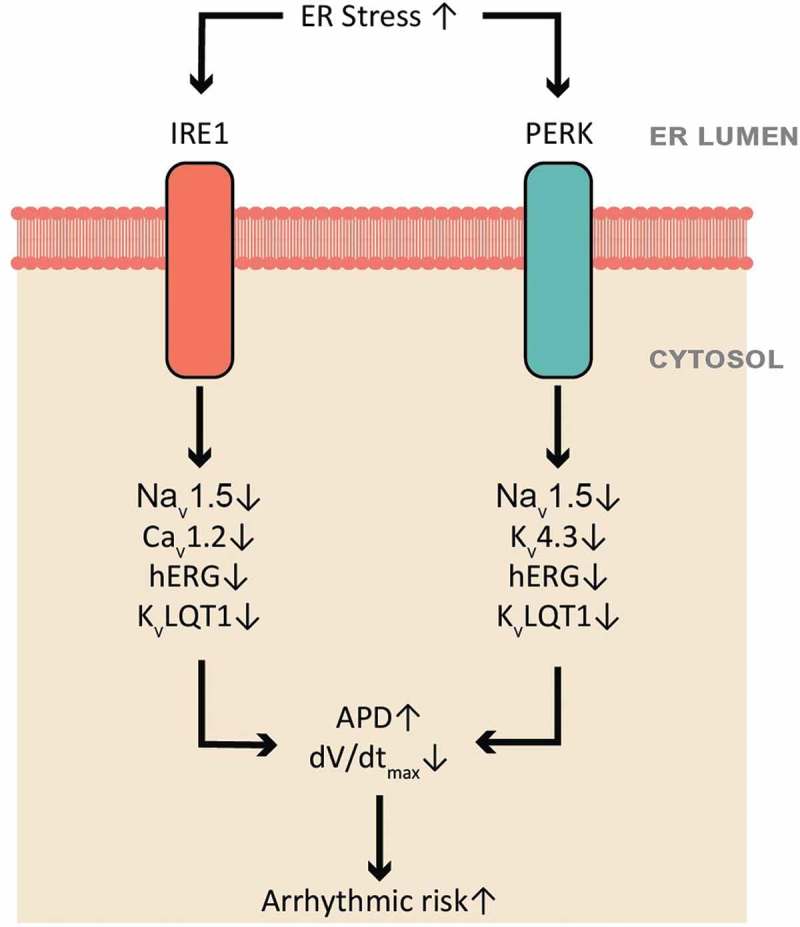

The UPR may contribute to downregulations of other ion channels in heart failure. Recently, our group reported downregulation of multiple cardiac ion channels by tunicamycin-induced UPR activation in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) (Figure 2) [62]. The downregulation of multiple cardiac ion channels corresponds to the APD prolongation and dV/dtmax reduction [62]. With the help of specific inhibitors of the PERK and IRE1 arm, we identified PERK-dependent regulation of Nav1.5, Kv4.3, human rapid delayed rectifying K+ channel (hERG), and KvLQT1 but not Cav1.2, and IRE1-dependent regulation of Nav1.5, Cav1.2, hERG, and KvLQT1 but not of Kv4.3 (Figure 3) [62]. Inhibition of either the PERK or IRE1 arm led to a shortened APD and recovered dV/dtmax. This suggests that PERK- and IRE1-mediated channel downregulations are specific for a certain set of channels, and that some cross talk exists between the PERK and IRE1 arms of UPR. The determinants of the specificity on channel regulation are unknown currently. Some ion channel β subunits are also downregulated in cardiomyopathy. The extent to which these changes are the result of the UPR requires further investigation.

Figure 2.

Tunicamycin-induced UPR activation alters the morphology of the action potential with prolonged action potential duration and decreased dV/dtmax of hiPSC-CMs, by decreasing all major cardiac ion channel currents.

Figure 3.

A summarized scheme of the UPR regulation on human cardiac ion channels. Activated UPR downregulates selective ion channels, leads to prolonged APD and reduced dV/dtmax, which can contribute to electrical remodeling and arrhythmias. The PERK branch downregulates Nav1.5, Kv4.3, hERG, and KvLQT1, while the IRE1 branch downregulates Nav1.5, Cav1.2, hERG, and KvLQT1.

Activated UPR induces a positive shift of the V1/2 of INa steady state activation that can be reversed partially by PERK inhibition with GSK2606414 and completely by IRE1 inhibition with 4µ8C [62], suggesting that the UPR results in changes in post-translational modifications of Nav1.5 or possibly changes in associated channel subunits. It is noteworthy that inhibition of IRE1 under physiological condition downregulates Cav1.2, hERG and KvLQT1 and prolongs the APD, indicating that certain IRE1 activity may be necessary to maintain these channels under physiological conditions. Inhibition of either PERK or IRE1 shows partial reversal of electrical remodeling, suggesting that the ATF6α arm may play a role in electrical remodeling or that there are overlapping effects of the UPR arms.

It is likely that some of the UPR effects are secondary to UPR-mediated changes that indirectly modify cardiac electrophysiology. For example, the activated UPR may affect ion channels or pumps that determine the resting membrane potentialf, thereby affecting the behavior of voltage-gated channels. Kir2.x, Na/K pump, Kir3.x (conducting IK,ACh) and Kir6.2 (conducting IK,ATP) in atria, and HCN channels (conducting If) for nodal cells are important determinants of the maximum diastolic depolarization. Downregulations of some of these channels have been reported in cardiomyopathy [64–68]. The role of the UPR in these changes remains to be determined.

Oxidative stress induced by the UPR [50,69,70] can also modulate cardiac ion channels [7,71,72]. Other mechanisms of arrhythmia under ER stress include altered Ca2+ homeostasis. Under prolonged ER stress, Ca2+ release from the ER is increased [19], which can not only activate signaling pathways of cell apoptosis but also induce triggered activity that can cause cardiac arrhythmias. ER-dependent ion channel glycosylation is also altered with UPR activation. A recent study shows that only a fully glycosylated cardiac Nav1.5 is trafficked normally [73]. Our group observed altered Nav1.5 glycosylation under UPR activation, which was reversed by IRE1 inhibition (unpublished data). Therefore, altered glycosylation during ER stress may contribute to ion channel alterations and arrhythmic risk.

Blocking UPR to raise ion channels as a treatment of arrhythmia

There is considerable literature to support the idea that UPR inhibition is beneficial in heart disease including ischemia/reperfusion [74], acute myocardial infarction [48,53,75,76], and chronic ischemic heart failure [47,57,77]. None of these studies looked at electrical remodeling, however. Our recent study shows that activated UPR downregulates multiple cardiac ion channels [6,62]. Therefore, blocking the UPR to reverse arrhythmogenic channel downregulation may be a new paradigm of maintaining ion channel activity to prevent arrhythmia. Electrical remodeling can be partially reversed by inhibition of either the PERK or IRE1 arm [62]. Chemical chaperones, such as 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) and taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) have been reported to reduce the ER stress by preventing misfolded protein aggregation and by suppressing the elevation of UPR sensors and effectors in hypertension and obesity-induced cardiac hypertrophy [78,79]. They show significant effects on reduced cardiac damage, improved vascular function in hypertension, and alleviation of compromised fractional shortening and cardiomyocyte contractile [78,79]. Analogues of 4-PBA such as 2-POAA-OMe, 2-POAA-NO2, and 2-NOAA have been found to suppress the induction of Grp78 and CHOP and to inhibit the IRE1 and ATF6α pathways [80]. Therefore, TUDCA, 4-PBA and its analogues may be used to suppress UPR activation and reverse the downregulation of cardiac ion channels.

While blocking the UPR activation appears logical to prevent arrhythmias, this signaling cascade has shown to have protective and harmful effects in certain circumstances [23,81–83]. On one hand, homozygous knockout animal models of several UPR sensors and effectors are potentially harmful or even lethal (reviewed in [84]). On the other hand, inhibition of the PERK arm with apelin-13 protects the heart from ischemia-induced ER stress [85]. Mice with inducible cardiac-specific PERK knockout have been shown to have normal heart function and not suffer from diabetes [53]. Nevertheless, the mouse heart ejection fraction is slightly decreased in response to chronic transverse aortic constriction when compared to control mice [53]. Therefore, partial or temporary inhibition of the UPR sensors or organ-specific gene therapy may be the safer alternative. Moreover, timing of inhibition may matter. Further investigation and understanding of the UPR will help overcome these limitations and discover more precisely targeting agents or time-limited treatment approaches.

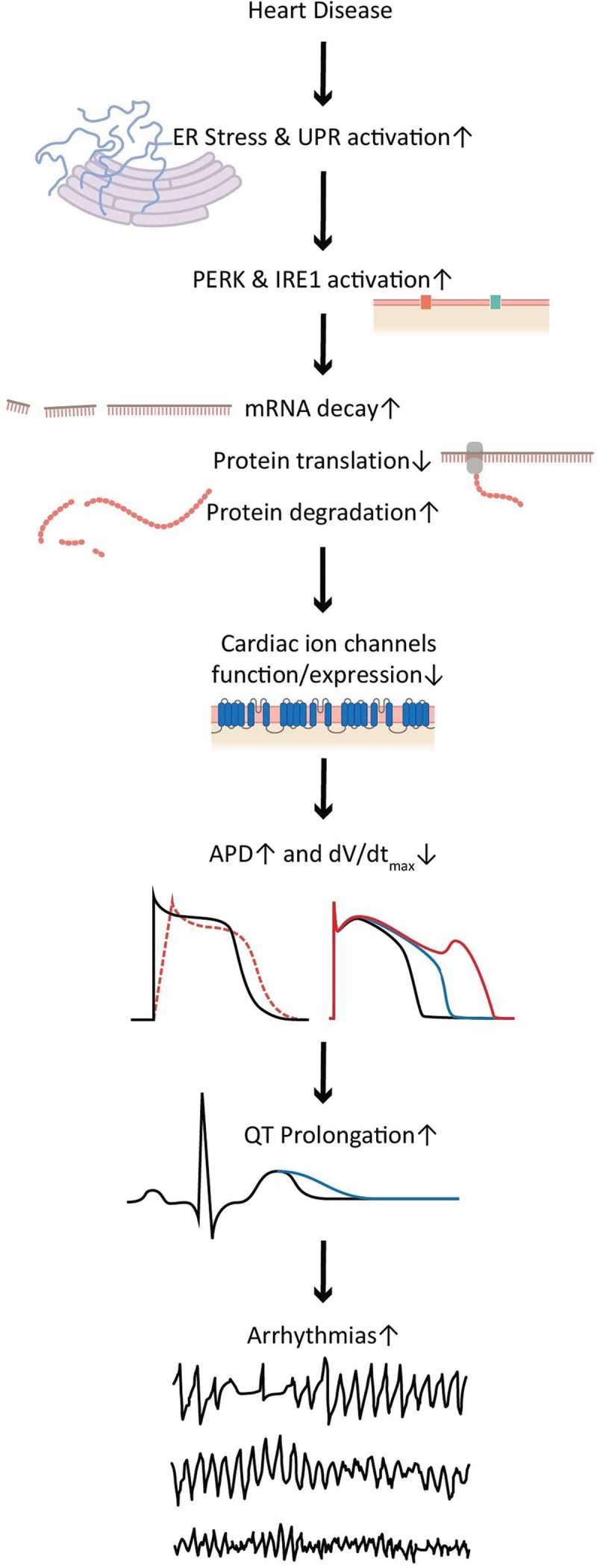

Summary

Cardiac injury results in UPR activation, which induces ion channel downregulations. These downregulations can explain some of the arrhythmic risk (Figure 4). Blocking UPR activation can raise ion channel levels and may represent a new and potentially fruitful antiarrhythmic paradigm.

Figure 4.

A summary of the UPR activation causing arrhythmias.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [SCD: R01 HL104025] and Rhode Island Foundation [ML: 20154145].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Liu M, Yang K-C, Jr SC D.. Cardiac sodium channnel mutations: why so many phenotypes? Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(10):607–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu M, Gu L, Sulkin MS, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction causing cardiac sodium channel downregulation in cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;54:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pu J, Boyden PA.. Alterations of Na+ currents in myocytes from epicardial border zone of the infarcted heart: a possible ionic mechanism for reduced excitability and postrepolarization refractoriness. Circ Res. 1997;81(1):110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Valdivia CR, Chu WW, Pu J, et al. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38(3):475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ufret-Vincenty CA, Baro DJ, Lederer WJ, et al. Role of sodium channel deglycosylation in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias in heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(30):28197–28203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gao G, Xie A, Zhang J, et al. Unfolded protein response regulates cardiac sodium current in systolic human heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6(5):1018–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu M, Liu H, Dudley SC Jr.. Reactive oxygen species originating from mitochondria regulate the cardiac sodium channel. Circ Res. 2010;107(8):967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu M, Shi G, Yang KC, et al. Role of protein kinase C in metabolic regulation of the cardiac Na+ channel. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(3):440–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Valenzeno DP, Tarr M. Calcium as a modulator of photosensitized killing of H9c2 cardiac cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74(4):605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, et al. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current (Ito). J Physiol. 2003;546(Pt 1):5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rosati B, McKinnon D. Regulation of ion channel expression. Circ Res. 2004;94(7):874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Scholz EP, Welke F, Joss N, et al. Central role of PKCα in isoenzyme-selective regulation of cardiac transient outward current Ito and Kv4.3 channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51(5):722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Janse MJ. Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61(2):208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li GR, Lau CP, Ducharme A, et al. Transmural action potential and ionic current remodeling in ventricles of failing canine hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(3):H1031–H1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nuss HB, Kaab S, Kass DA, et al. Cellular basis of ventricular arrhythmias and abnormal automaticity in heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(1 Pt 2):H80–H91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arrieta A, Blackwood EA, Glembotski CC. ER Protein quality control and the unfolded protein response in the heart. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2018;414:193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2656–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334(6059):1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ni L, Zhou C, Duan Q, et al. β-AR blockers suppresses ER stress in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Luo T, Chen B, Wang X. 4-PBA prevents pressure overload-induced myocardial hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Chem-Biol Interact. 2015;242:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ortega A, Roselló-Lletí E, Tarazón E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces different molecular structural alterations in human dilated and ischemic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thuerauf DJ, Hoover H, Meller J, et al. Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase-2 expression is regulated by ATF6 during the endoplasmic reticulum stress sesponse: intracellular signaling of calcium stress in a cardiac myocyte model system. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(51):48309–48317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thuerauf DJ, Marcinko M, Gude N, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response in infarcted mouse heart and hypoxic cultured cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;99(3):275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jin J-K, Blackwood EA, Azizi K, et al. ATF6 decreases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion damage and links ER stress and oxidative stress signaling pathways in the heart. Circ Res. 2017;120(5):862–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Guo R, Liu W, Liu B, et al. SIRT1 suppresses cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy: an insight into endoplasmic reticulum stress response mechanism. Int J Cardiol. 2015;191:36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lakshmanan AP, Harima M, Suzuki K, et al. The hyperglycemia stimulated myocardial endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress contributes to diabetic cardiomyopathy in the transgenic non-obese type 2 diabetic rats: a differential role of unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(2):438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jensen BC, Bultman SJ, Holley D, et al. Upregulation of autophagy genes and the unfolded protein response in human heart failure. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10(1):1051–1058. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kitakaze M, Tsukamoto O. What is the role of ER stress in the heart?: introduction and series overview. Circ Res. 2010;107(1):15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Groenendyk J, Sreenivasaiah PK, Kim DH, et al. Biology of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2010;107(10):1185–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Glembotski CC. Roles for the sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum in cardiac myocyte contraction, protein synthesis, and protein quality control. Physiol. 2012;27(6):343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang X, Xu L, Gillette TG, et al. The unfolded protein response in ischemic heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;117:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Minamino T, Komuro I, Kitakaze M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2010;107(9):1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Liu M, Dudley SC. Targeting the unfolded protein response in heart diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18(7):719–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu M, Jr SC D. Role for the unfolded protein response in heart disease and cardiac arrhythmias. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Moreno JA, Halliday M, Molloy C, et al. Oral treatment targeting the unfolded protein response prevents neurodegeneration and clinical disease in prion-infected mice. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(206):206ra138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li Z, Zhang T, Dai H, et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in myocardial apoptosis of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;41(1):58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, et al. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase is required for the development of the skeletal systme, postnatal growth and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(11):3864–3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yang L, Zhao D, Ren J, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and protein quality control in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Glembotski CC. The role of the unfolded protein response in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(3):453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Scull C, Tabas I. Mechanisms of ER stress-induced apoptosis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2792–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hasty AH, Harrison DG. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and hypertension - a new paradigm? J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):3859–3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang S, Binder P, Fang Q, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart: insights into mechanisms and drug targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(8):1293–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wei K, Liu L, Xie F, et al. Nerve growth factor protects the ischemic heart via attenuation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress induced apoptosis by activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(1):83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Li C, Hu M, Wang Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide preconditioning protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through inhibition of endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(7):7740–7751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hou JY, Liu Y, Liu L, et al. Protective effect of hyperoside on cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury through inhibition of ER stress and activation of Nrf2 signaling. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(1):76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tadimalla A, Belmont PJ, Thuerauf DJ, et al. Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor Is an ischemia-inducible secreted endoplasmic reticulum stress response protein in the heart. Circ Res. 2008;103(11):1249–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Xin W, Li X, Lu X, et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated apoptosis in a heart failure model induced by chronic myocardial ischemia. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27(4):503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Shi ZY, Liu Y, Dong L, et al. Cortistatin improves cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction in rats by suppressing myocardial apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2016;22(1):83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Toko H, Takahashi H, Kayama Y, et al. ATF6 is important under both pathological and physiological states in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(1):113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Santos C, Nabeebaccus A, Shah A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Nox-mediated reactive oxygen species signaling in the peripheral vasculature: potential role in hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(1):121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Okada K, Minamino T, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing heart after aortic constriction: possible contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 2004;110(6):705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Dromparis P, Paulin R, Stenson TH, et al. Attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel therapeutic strategy in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2013;127(1):115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu X, Kwak D, Lu Z, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure and lung remodeling. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):738–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Li Z, Zhang T, Dai H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in myocardial apoptosis of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. J Endocrinol. 2008;196(3):565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Liu Z-W, Zhu H-T, Chen K-L, et al. Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) signaling pathway plays a major role in reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dickhout JG, Carlisle RE, Austin RC. Interrelationship between cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease: endoplasmic reticulum stress as a mediator of pathogenesis. Circ Res. 2011;108(5):629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Liu Y, Wang J, Qi SY, et al. Reduced endoplasmic reticulum stress might alter the course of heart failure via caspase-12 and JNK pathways. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(3):368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Fu HY, Okada K, Liao Y, et al. Ablation of C/EBP homologous protein attenuates endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction induced by pressure overload. Circulation. 2010;122(4):361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sawada T, Minamino T, Fu HY, et al. X-box binding protein 1 regulates brain natriuretic peptide through a novel AP1/CRE-like element in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(6):1280–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Isodono K, Takahashi T, Imoto H, et al. PARM-1 is an endoplasmic reticulum molecue involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in rat cardiac myocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Dally S, Monceau V, Corvazier E, et al. Compartmentalized expression of three novel sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ATPase 3 isoforms including the switch to ER stress, SERCA3f, in non-failing and failing human heart. Cell Calcium. 2009;45(2):144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Liu M, Shi G, Zhou A, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response downregulates cardiac ion channels in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;117:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Forrester M, Eyler C, Rich J. Bacterial flavohemoglobin: a molecular tool to probe mammalian nitric oxide biology. BioTechniques. 2011;50:41–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Borlak J, Thum T. Hallmarks of ion channel gene expression in end-stage heart failure. FASEB J. 2003;17(12):1592–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rose J, Armoundas AA, Tian Y, et al. Molecular correlates of altered expression of potassium currents in failing rabbit myocardium. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(5):H2077–H2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Verkerk AO, Wilders R, Coronel R, et al. Ionic remodeling of sinoatrial node cells by heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108(6):760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cerbai E, Pino R, Porciatti F, et al. Characterization of the hyperpolarization-activated current, If, in ventricular myocytes from human failing heart. Circulation. 1997;95(3):568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zicha S, Fernandez-Velasco M, Lonardo G, et al. Sinus node dysfunction and hyperpolarization-activated (HCN) channel subunit remodeling in a canine heart failure model. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66(3):472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Safiedeen Z, Rodríguez-Górnez I, Vergori L, et al. Temporal cross talk between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria regulates oxidative stress and mediates microparticle-induced endothelial dysfunction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;26(1):15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lebeau J, Saunders JM, Moraes VWR, et al. The PERK arm of the unfolded protein response regulates mitochondrial morphology during acute endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Reports. 2018;22(11):2827–2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Jeong EM, Liu M, Sturdy M, et al. Metabolic stress, reactive oxygen species, and arrhythmia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;52(2):454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Liu M, Sanyal S, Gao G, et al. Cardiac Na+ current regulation by pyridine nucleotides. Circ Res. 2009;105(8):737–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Mercier A, Clément R, Harnois T, et al. Nav1.5 channels can reach the plasma membrane through distinct N-glycosylation states. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850(6):1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wang G, Huang H, Zheng H, et al. Zn2+ and mPTP mediate endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibition-induced cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;174(1):189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Li R-J, He K-L, Li X, et al. Salubrinal protects cardiomyocytes against apoptosis in a rat myocardial infarction model via suppressing the dephosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(1):1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Luo T, Kim JK, Chen B, et al. Attenuation of ER stress prevents post-infarction-induced cardiac rupture and remodeling by modulating both cardiac apoptosis and fibrosis. Chem-Biol Interact. 2015;225:90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Song XJ, Yang CY, Liu B, et al. Atorvastatin inhibits myocardial cell apoptosis in a rat model with post-myocardial infarction heart failure by downregulating ER stress response. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8(7):564–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kassan M, Galán M, Partyka M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in cardiac damage and vascular endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive mice. Atertio Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(7):1652–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ceylan-Isik AF, Sreejayan N, Ren J. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperon tauroursodeoxycholic acid alleviates obesity-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50(1):107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [80].Zhang H, Nakajima S, Kato H, et al. Selective, potent blockade of the IRE1 and ATF6 pathways by 4-phenylbutyric acid analogues. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170(4):822–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Martindale JJ, Fernandez R, Thuerauf D, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress gene induction and protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury in the hearts of transgenic mice with a tamoxifen-regulated form of ATF6. Circ Res. 2006;98(9):1186–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Pan YX, Lin L, Ren AJ, et al. HSP70 and GRP78 Induced by endothelin-1 pretreatment enhance tolerance to hypoxia in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(Suppl 1):S117–S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Vitadello M, Penzo D, Petronilli V, et al. Overexpression of the stress-protein Grp94 reduces cardiomyocyte necrosis due to calcium overload and simulated ischemia. FASEB J. 2003;17(8):923–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Cornejo V, Pihán P, Vidal R, et al. Role of the unfolded protein response in organ physiology: lessons from mouse models. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(12):962–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Tao J, Zhu W, Li Y, et al. Apelin-13 protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibition of ER-dependent apoptotic pathways in a time-dependent fashion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(4):H1471–H1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]