Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is one of the most challenging aspects of hepatic pathology both because of its inherent complexity and because a patient’s comorbidities may interfere with interpretation. Biopsies may be performed for several reasons. Usually, a liver biopsy is done in suspected DILI to aid in diagnosis because of some clinical uncertainty. A biopsy also may be used to assess the severity of the liver damage or to exclude serious findings like duct loss, necrosis, or advanced fibrosis. Frequently there are issues of differential diagnosis. There may be a known preexisting liver disease or a patient’s comorbidities may have complex secondary effects on the liver. With newer drugs that have little or no record of liver injury, a biopsy may provide information on the mechanism of injury. This was the case with the experimental agent fialuridine, where liver tissue from biopsy and explant provided the confirmation that mitochondrial injury was the source of the problem.1,2

The role of the pathologist in evaluating cases of DILI is to provide expert interpretation of the tissue changes considering a patient’s medical and pharmaceutical history. Because of the potential complexity of these cases, a systematic approach is recommended (Box 1). The first step is objective and unbiased evaluation of the changes, organizing them into the defined patterns of injury common to many liver diseases. Table 1 and the body of this review highlight the most common patterns of significant injury that have been identified in cases of DILI.3,4 Tumors are excluded from the classification, because the evaluation in such cases is focused on tumor diagnosis rather than attributing the tumor development to a particular agent. Once the pattern(s) of injury are defined, the pathologist must correlate the findings with the history, sorting out findings that can be attributed to nondrug etiologies, which may require work-up for unusual causes of liver injury. Resources are available for finding patterns of histologic injury due to drugs. These include the National Intitutes of Health LiverTox Web site (https://livertox.nih.gov/) and DILI book chapters in references devoted to hepatic pathology. Drugs that have been recently approved (especially checkpoint inhibitors,5 tyrosine kinase inhibitors,6 monoclonal antibodies,7 and small molecule immunomodulators8) may require searches of the biomedical literature databases. The final pathology report should include information on the pattern of injury, the severity of injury, and the differential diagnosis.

Box 1: Systematic approach to the histologic evaluation of potential drug-induced liver injury.

Identify the pattern of injury

- Identify the suspect agents

- Drug, herbal, environmental exposures

- Appropriate time line?

- Appropriate histologic injury pattern?

Exclude other causes of injury (or not)

- Draw conclusions

- Comment on the elements in step 2

- Comment on any potential alternative etiologies that may require additional testing

Table 1.

Non-neoplastic patterns of injury observed in drug-induced liver injury and their differential diagnosis

| Pattern | Characteristic Features | Common Alternate Etiologies | Uncommon Alternate Etiologies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necroinflammatory | Acute (lobular) hepatitis | Predominantly lobular inflammation with/without confluent or bridging necrosis; lobular disarray; absence of or only minimal cholestasis | Acute viral or autoimmune hepatitis | |

| Chronic (portal) hepatitis | Portal inflammation with interface hepatitis, with or without portal-based fibrosis; no cholestasis | Chronic viral or autoimmune diseases | Early PBC/PSC, EBV, or CMV-associated hepatitis (mononucleosis pattern), collagen-vascular disease, celiac disease, CVID | |

| Granulomatous hepatitis | Typically non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation dominates pattern | Sarcoidosis, PBC | Fungal, mycobacterial, and atypical bacterial or rickettsial infections, CVID | |

| Massive or submassive necrosis | Complete loss of hepatocytes over large areas, with regenerative nodules | Fulminant viral hepatitis | ||

| Zonal coagulative necrosis | Zone 3 or 1 coagulative necrosis, usually without significant inflammation | Hypoxic-ischemic injury (zone 3) | Necrotizing viral infections (usually nonzonal) | |

| Cholestatic | Cholestatic hepatitis | Acute or chronic hepatitis pattern plus zone 3 cholestasis | Acute viral or autoimmune hepatitis | Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis |

| Acute intrahepatic cholestasis | Hepatocellular and/or canalicular cholestasis in zone 3, minimal inflammation | Sepsis, acute large duct obstruction, postsurgical jaundice | Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis | |

| Chronic cholestasis (vanishing bile duct syndrome) | Duct sclerosis and loss, periportal cholatestasis, portal-based fibrosis, copper accumulation | PSC | Biliary tree infections in the immunosuppressed patient, ductopenic GVHD, idiopathic adulthood ductopenia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, IgG4-related systemic sclerosis | |

| Chronic cholestasis (PBC-like cholangiodestructive) | Florid duct injury with duct loss, periportal cholatestasis, copper | Primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune cholangitis, chronic large duct obstruction | Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis | |

| Steatotic | Microvesicular steatosis | Diffuse microvesicular steatosis | Alcohol, fatty liver of pregnancy | |

| Macrovesicular steatosis | Macrovesicular steatosis without significant portal or lobular inflammation, no cholestasis | Very common finding in general population, alcohol, obesity, diabetes | Celiac disease | |

| Steatohepatitis | Zone 3 ballooning injury, sinusoidal fibrosis, Mallory bodies, variable inflammation, and steatosis | As for macrovesicular steatosis | ||

| Vascular | Sinusoidal dilation/peliosis | Sinusoidal alterations, may have sinusoidal fibrosis | Artifactual, acute congestion, nearby mass lesions | Bacillary angiomatosis |

| VOD/SOS/Budd-Chiari | Occlusion or loss of central veins, thrombosis, with or without central hemorrhage and necrosis | |||

| Hepatoportal sclerosis | Disappearance of portal veins | Arteriohepatic dysplasia | ||

| Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Diffuse nodular transformation, may have sinusoidal fibrosis | Collagen-vascular diseases, lymphoproliferative diseases | ||

| Miscellaneous changes and pigment accumulations | Glycogenosis | Diffuse hepatocyte swelling with very pale bluish-gray cytoplasm | Type 1 diabetes mellitus, obesity | |

| Ground-glass change | Diffuse homogenization of cell cytoplasm due to induction of smooth endoplasmic reticulum | |||

| Cytoplasmic inclusions | Discrete PAS-positive or -negative cytoplasmic inclusions | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency, long-standing hepatic congestion, megamitochondria | ||

| Gold pigment | Granular black pigment in Kupffer cells | Anthracosis | Malarial pigment | |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; CVID, common variable immune deficiency; EBV, epstein -barr virus; GVHD, graft versus host disease; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

NECROINFLAMMATORY PATTERNS

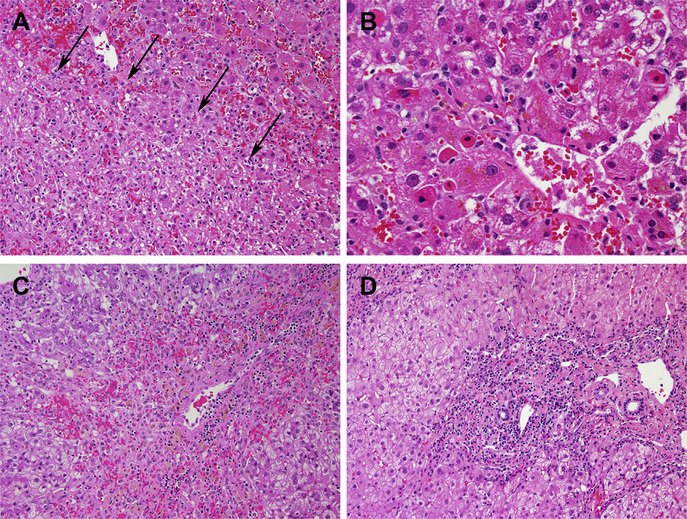

Histologic injury in DILI often manifests as inflammation or hepatocellular necrosis or a combination of the 2 (Fig. 1). More than a third of cases of suspected DILI in the DILI Network (DILIN) show significant necroinflammatory injury without visible cholestasis, and, if cases of acute hepatitis with mild cholestasis are included, the total reaches nearly half.3 There are 2 basic patterns of inflammation, which the authors have termed, acute hepatitis and chronic hepatitis, although it should be remembered that these represent histologic patterns important for differential diagnosis and do not necessarily convey information about the time course of the injury. Both patterns can range in severity from mild to marked and distinction between the 2 can be difficult at both extremes.

Fig. 1.

Necroinflammatory patterns. (A, B) Acute hepatitis due to azithromycin. There were irregular, nonzonal regions of necrosis (arrows [A]) whereas numerous apoptotic hepatocytes and foci of lobular inflammation were seen near central veins (B). (C) Zone 3 necrosis due to acetaminophen. A mild mononuclear infiltrate is present in the necrotic zone. (D) Chronic hepatitis-like portal inflammation due to atorvastatin. (A) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×200; (B) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×400; (C) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×100; and (D) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification × 200.

Acute hepatitic patterns involve the parenchyma more than the portal areas, with hepatocyte apoptosis and numerous foci of lymphocytes and macrophages disrupting the normal sinusoidal architecture of the liver, a finding termed lobular disarray. Lobular disarray often is associated with features of regeneration, including mitotic activity and hepatocyte rosettes. Portal inflammation with interface hepatitis also may be severe but in proportion to the parenchymal injury. Plasma cells and eosinophils may be seen, particularly in portal areas. Plasma cells at the periphery of the portal area raise a differential diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. There may be perivenular (zone 3) necrosis. This latter finding has been associated with particular agents, including diclofenac9 and ipilimumab.10 When cholestasis is present in severe acute hepatitis, it usually is mild and difficult to identify. Such cases are classified as acute cholestatic hepatitis or acute hepatitis with cholestasis. In studies, they may be grouped with either acute hepatitis without evident cholestasis or as one of the forms of cholestatic hepatitis.3 Many drugs can show an acute hepatitic pattern, including checkpoint inhibitors,11 infliximab (and other tumor necrosis factor α antagonists),12 isoniazid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and agents used to treat psychiatric disorders. Severe cases of acute hepatitis present with aminotransferases elevated 10-fold to 30-fold above the upper limit of normal and usually are jaundiced.3

Chronic (or portal-predominant) hepatitic patterns resemble chronic viral hepatitis histologically, with portal inflammation visible at low magnification and only mild to moderate parenchymal inflammation. Hepatocyte rosettes can be seen when the overall inflammation is severe, but the presence of lobular disarray prompts classification as an acute hepatitic pattern. Similarly, cholestasis is not seen in this pattern of injury—these cases should be considered a form of cholestatic hepatitis. Fibrosis sometimes is present and may bridge between portal areas as in the case of nitrofurantoin injury.13 Many of the drugs that cause acute hepatitis also may show a chronic hepatitic pattern, such as nitrofurantoin,14 minocycline,14 isoniazid,15 and atorvastatin.16 Clinically, patients with chronic hepatitis pattern present with only modest elevation in aminotransferases and normal bilirubin levels.

Hepatocellular necrosis is a frequent finding in DILI. In the DILIN study, a quarter of the biopsies showed some degree of confluent necrosis, and most of the time it followed a zone 3-centered distribution.3 When necrosis is severe, it may involve multiple contiguous hepatic acini and clinically these patients present with fulminant hepatic failure. Zone 1 necrosis is rare and usually related to a direct hepatic toxin like phosphorus rather than a drug.17 Zone 3 coagulative necrosis is the classic injury pattern of acetaminophen and it is related to the accumulation of the toxic metabolite in a susceptible population of cells. There is minimal inflammation with acetaminophen, with infiltration of macrophages and some neutrophils into the region of necrosis (see Fig. 1C). Pure zone 3 necrosis without significant inflammation is unusual in other drugs and should prompt a search for occlusive vascular injury.

Other patterns of necroinflammatory injury include granulomatous hepatitis and the sinusoidal lymphocytosis pattern. The latter is the typical inflammatory pattern for EBV-related hepatitis but also may be seen with some drugs, such as phenytoin.18 This pattern is most similar to the chronic hepatitic pattern because there is portal inflammation with less lobular inflammation. In sinusoidal lymphocytosis, there is beading of lymphocytes and macrophages in the sinuses without infiltration into the cords of liver cells. In situ hybridization for EBV should be performed to exclude that diagnosis. Granulomatous hepatitis is diagnosed when granulomatous inflammation is dominant. Microgranulomas, which are small collections of macrophages in the range of 1 to 3 hepatocytes in size are frequently observed in DILI and in non-DILI liver disease and should not be used to classify the case as granulomatous hepatitis. The granulomas in DILI-related granulomatous hepatitis are larger and do not have necrotic centers (which would suggest infection). They may be well formed and sarcoid-like, as has been seen with interferon, or poorly formed, with infiltration by lymphocytes and illdefined edges. Fibrin ring granulomas, an unusual type of lipogranuloma centered around a lipid vacuole and surrounded by fibrin and epithelioid histiocytes, have been observed in several types of DILI, including injury due to allopurinol19 and checkpoint inhibitors.20 Fungal and mycobacterial infection need to be excluded, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. Depending on the location of the granulomas, other diseases, such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), may need to be considered.

Finally, the inflammatory infiltrate may be mild, in the range of reactive forms of hepatitis observed in collagen-vascular diseases. Such cases might have a sprinkling of inflammation in the portal areas with an occasional focus of interface hepatitis and widely scattered foci of lobular inflammation. The presence of clusters of pigmented macrophages may suggest a more severe hepatitis has come and gone, but there may be little to suggest any injury. The clinical significance of these mild forms of injury is unknown.

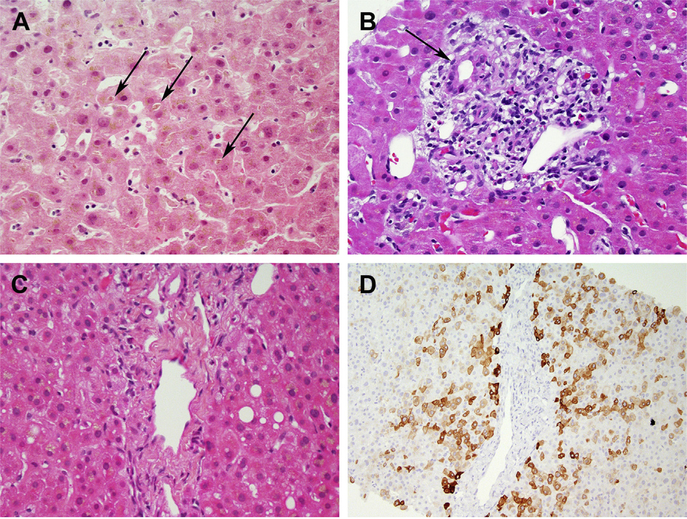

CHOLESTATIC INJURY PATTERNS

Cholestasis may be observed in 2 basic forms in the liver: as the accumulation of bile or as the accumulation of bile salts. In the former situation, bile can be found within hepatocytes, dilated canaliculi, cholangioles or the interlobular ducts. Bile pigment also can be found in macrophages, particularly in zone 3. Cytoplasmic bile, whether in macrophages or hepatocytes, can be difficult to differentiate from other pigments, such as hemosiderin and lipofuscin. Special stains may be useful in differentiating pigments. Bile stains can be used to demonstrate bile directly, and iron and copper have a pale counterstain that allows the natural greenish-brown bile pigment to be more clearly seen. Bile within canaliculi and duct structures can be identified without the use of special stains. The location of the bile is important because ductal and ductular bile accumulation are unusual in DILI. Bile salts accumulate in the periportal hepatocytes in chronic cholestasis, causing the cytoplasm to become pale and vacuolated. This change may be termed cholate stasis, pseudoxanthomatous change, or feathery degeneration, depending on the age of the publication. Copper accumulates in these hepatocytes and can be identified directly with copper stains or indirectly with orcein or Victoria blue stains. Immunohistochemistry for keratin 7 may be positive in periportal hepatocytes in chronic cholestasis.

There are 3 main patterns of cholestatic liver injury seen in DILI (Fig. 2), although it is possible to subdivide these into additional categories based on the non-DILI differential diagnosis. The most common pattern is the mixed pattern of cholestatic hepatitis, accounting for almost 30% of the cases in the DILIN study.3 These cases have portal and/or parenchymal inflammation as well as canalicular and hepatocellular cholestasis. The cholestasis begins in zone 3 but can be extensive. The distribution and severity of inflammation can replicate the inflammatory patterns, outlined previously. Cases of acute hepatitic inflammatory injury usually have mild cholestasis that may be difficult to identify without special stains. When the hepatitic component is less severe, the cholestasis is usually easier to identify. Other features of cholestatic injury, including bile duct injury or loss and hepatocellular swelling from cytoplasmic bile, also may be present. Liver enzymes show a bimodal distribution. The cases of acute hepatitis with cholestasis present clinically like acute hepatitis, with marked elevations in aminotransferases and jaundice. In contrast, cases of inflammation and more cholestasis have ratios of aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase in the cholestatic range.3 Cholestatic hepatitis has a non-DILI differential diagnosis that varies according the inflammatory pattern.

Fig. 2.

Cholestatic patterns. (A) Acute cholestasis due to an anabolic steroid. Canalicular bile plugs in zone 3 (arrows) are present but there is minimal inflammation. (B) Bile duct injury (arrow) due to amoxicillin-clavulanate. Cholestasis (not pictured) was seen in zone 3. (C, D) Chronic cholestasis and bile duct loss due to gabapentin. The portal areas show no ducts, as confirmed by staining for keratin 7 (D). (A) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×400; (B) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×400; (C) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×400; and (D) Keratin 7 immunohistochemistery, original magification ×200).

When the inflammatory component disappears but the cholestasis remains, the pattern becomes acute or intrahepatic cholestasis. This is the classic pattern of injury of the contraceptive and anabolic steroids21 but may be seen with other drugs as well. There may be a minimal inflammatory infiltrate: scattered lymphocytes in portal areas and clusters of pigmented macrophages in zone 3. As with cholestatic hepatitis, duct injury or loss may be seen. Duct loss without other chronic cholestatic features may occur as in cases of azithromycin DILI.22

Cases of features of chronic cholestasis tend to show increased fibrosis associated with ductular reaction. The bile ducts usually show some degree of injury, which may mimic the duct injury of PBC or primary sclerosing cholangitis, but duct loss is not required. This pattern of injury is important to recognize because it may take longer for the liver enzymes to return to normal compared with other types of liver injury.23,24

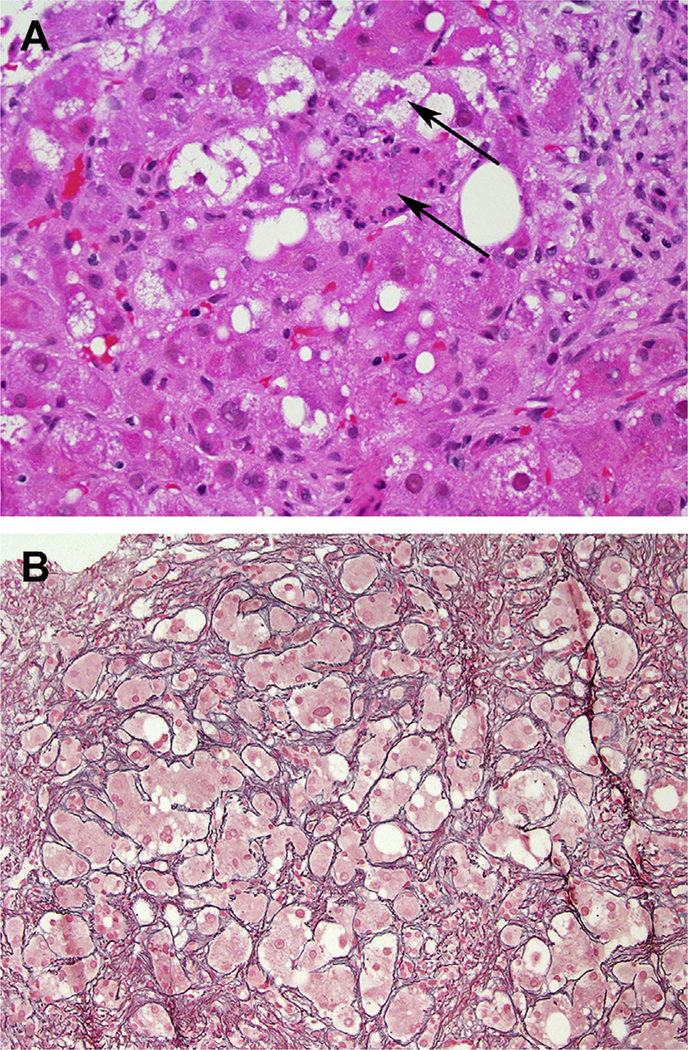

STEATOSIS AND STEATOHEPATITIS

Liver diseases related to macrovesicular steatosis, which include both alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), are among the most common in the world. When these patterns of injury are present in a suspected case of DILI, it is necessary to show that the common etiologies of fatty liver disease are not responsible for the changes. Some agents, such as tamoxifen25 or methotrexate,26 can mimic the patterns of NAFLD exactly. This includes mimicking steatohepatitis, with zone 3 ballooning injury and perisinusoidal fibrosis (Fig. 3). Careful attention to other changes, such as cholestasis, marked degrees of inflammation, vascular injury, and numerous apoptotic hepatocytes, may be necessary to identify features that might indicate the presence of drug injury. Demonstration that drug injury was present may require follow-up after discontinuation of the suspect drug and resolution, as was the result in a case of tamoxifen injury highlighted by the DILIN investigators in their study of chronic liver injury.23

Fig. 3.

Steatohepatitis due to methotrexate. (A) Ballooning injury with Mallory-Denk bodies (arrows). (B) Extensive perisinusoidal fibrosis seen in a reticulin stain. (A) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×400 and (B) Reticulin, original magnification ×200.

Some drugs interfere with lipid metabolism or induce steatogenic states by altering peripheral insulin resistance and this fact may provide an explanation for hepatic steatosis. This is particularly true for drugs that cause mitochondrial injury. Acetaminophen can interfere with mitochondrial function in several ways27 and steatosis often is seen in acetaminophen injury. Mitochondrial injury usually is present in cases of microvesicular steatosis. Microvesicular steatosis is defined as a foamy change in the hepatocyte cytoplasm with innumerable tiny vacuoles that fill the cytoplasm. Diffuse microvesicular change throughout the biopsy defines the pattern of microvesicular steatosis. There is limited differential diagnosis for diffuse microvesicular steatosis and almost all of the causes are drugs or toxins. Notable drugs associated with microvesicular steatosis include salicylates,28 amiodarone,29 linezolid30 and valproic acid.31 The nondrug causes include environmental toxins, alcohol (acute foamy degeneration), and fatty liver of pregnancy.

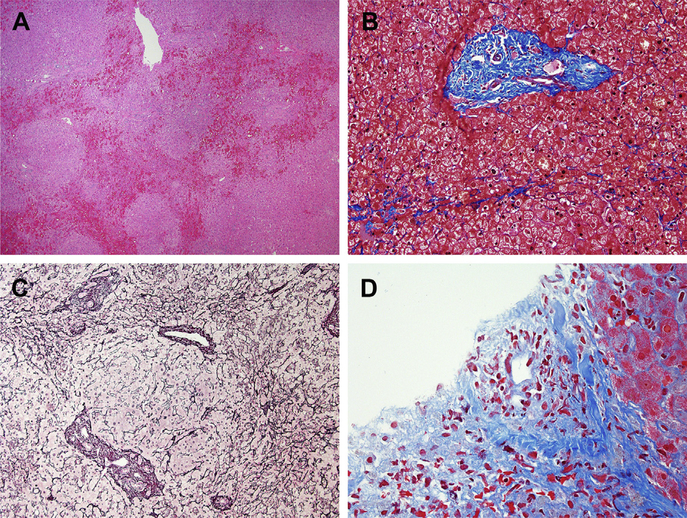

VASCULAR INJURY

Most of the DILI literature focuses on the hepatocyte, which is the most common target. Hepatocyte function and survival also can be secondarily affected by vascular injury. Drug-induced vascular injury can occur at any level, from the small portal veins to the large hepatic veins. Starting from the outflow side, oral contraceptives and other drugs that interfere with coagulation can cause hepatic venous thrombosis. Affected segments of the liver show massive hemorrhage and necrosis. Thrombi may be seen in the larger veins. Veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS) occurs with injury to the endothelium of the sinusoids and small hepatic veins. Mainly associated with stem cell transplant preparative regimens, VOD/SOS is diagnosed by characteristic narrowing and occlusion of hepatic veins by cells and loose connective tissue (Fig. 4D). The sinusoidal injury, although present, is difficult to recognize histologically, particularly when there is secondary hemorrhage and necrosis of perivenular hepatocytes. Venular endotheliitis with hemorrhage but without venous occlusion may be a component of acute hepatitis and has been reported as a finding in checkpoint inhibitor injury.11 As a finding in cases of suspected DILI in the DILIN study, venous endotheliitis was more common than either portal vein injury or VOD/SOS.3

Fig. 4.

Vascular injury patterns. (A-C) NRH and hepatoportal sclerosis due to oxaliplatin. A low-magnification overview shows areas of vascular congestion outlining nodules (A). The Masson trichrome stain showed that most of the small portal areas lacked a vein (B). Reticulin staining shows the characteristic nodular regeneration (C). (D) Veno-occlusive changes after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. A small vein shows nearly complete occlusion by loose collagen and cells. (A) Hematoxylin-Eosin, original magnification ×40; (B) Masson trichrome, original magnification ×200; (C) Reticulin, original magnification ×100; (D) Masson trichrome, original magnification ×400.

Injury to the sinuses and portal veins may be insidious, unlike the more dramatic clinical presentions stemming from outflow obstruction. Oxaliplatin32 and the purine analogues33 have been associated with nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) and noncirrhotic portal hypertension (Fig. 4). NRH may be easily overlooked on needle biopsies if reticulin stains are not performed or the pathologist is not comfortable with interpreting the changes. The mercaptopurines also may cause a cholestatic hepatitis, which may obscure underlying NRH. The key feature to identify is regular variation in hepatocyte plate width, with areas of compressed, atrophic liver cell plates arcing around zones of widened liver cell plates. Portal vein injury (hepatoportal sclerosis) is another subtle injury that has been observed with oxaliplatin and other agents. The portal veins may be slit-like or disappear or herniate into adjacent sinusoids. Because these changes may be seen on occasion in normal liver, it is important to assess each portal area to make sure that the findings are consistent throughout the biopsy. Sinusoidal dilation may accompany both NRH and portal venopathy.

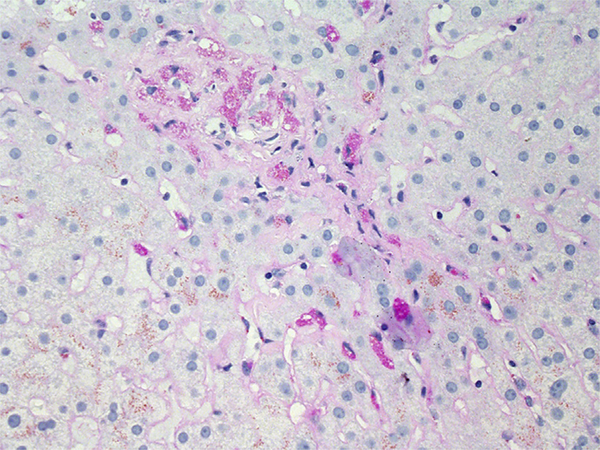

BIOPSIES WITH MINIMAL CHANGES

Sometimes the liver biopsy shows minimal changes or even look normal. As discussed previously, injury to the portal veins and NRH can be subtle but should be excluded on any biopsy with an apparently unremarkable appearance on routine stains, particularly if there is any suggestion of portal hypertension in the history. Patients who have recovered from a mild acute hepatitic injury may show only clusters of pigmented, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive macrophages in the parenchyma, marking the location of hepatocyte loss (Fig. 5). Other subtle changes include hepatocyte cytoplasmic inclusions or alterations. Ground-glass-like inclusions that mimic those of hepatitis B may be seen associated with polypharmacy in immunosuppressed patients. These often are strongly positive with PAS and variably sensitive to diastase digestion. Diffuse ground-glass-like changes may be seen with activation of endoplasmic reticulum or with diffuse glycogenosis. Czeczok and colleagues34 have outlined the entities associated with near-normal liver biopsies and it may be helpful to use these entities as a checklist when evaluating such cases.

Fig. 5.

Resolving injury due to nitrofurantoin. A biopsy performed during the resolving phase of DILI shows minimal changes, seen as clusters of pigmented macrophages highlighted by a PAS stain with diastase digestion (Periodic acid-Schiff with diastase, original magnification ×400).

PROGNOSTIC INFORMATION

Commonly used serum markers of liver injury (aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase) are not able to reliably predict clinical outcomes of DILI. Although there is a great interest in identifying novel serum and genetic biomarkers for DILI diagnosis and prognosis, current prediction algorithms, such as Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) index,35 combine clinical and laboratory values but do not include histologic findings.

Liver histology can provide prognostic information assisting clinical management. In the DILIN study,3 necrosis, fibrosis, microvesicular steatosis, cholangiolar cholestasis, ductular reaction, neutrophils, and portal venopathy were all associated with severe outcom, whereas granulomas and eosinophils3,36 were more likely to be noted in milder cases. In other studies, the degree of necrosis and the presence of ductular reaction were also found critical in predicting survival. Liver biopsy with more than 75% necrosis was associated with significant transplant-free mortality in a patient population with fulminant liver failure due to autoimmune hepatitis, DILI, or hepatitis virus infection.37

Liver biopsy also may raise concerns for delayed recovery from DILI. Biochemically cholestatic injury has been associated with persistent liver enzyme abnormalities.23 When cases were investigated with liver biopsy, it was shown that patients with bile duct loss were more likely to develop chronic liver injury. Bile duct loss during acute cholestatic hepatitis was found to be an early indicator of possible vanishing bile duct syndrome.38

Histologic findings can also guide the identification of serologic prognostic markers. After necrosis and apoptosis were shown to be associated with a worsened laboratory versus clinical course in animal models,39 a serum-based apoptotic index was proposed as as a prognostic tool.35,39 The index estimates the degree of apoptosis and necrosis in liver injury by measuring the ratio of full-length cytokeratin 18 and caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

There have been no systematic studies on the utility of liver biopsy in the diagnosis or management of DILI, although suspected DILI is a reasonable indication for liver biopsy.40 The European Association for the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines41 for DILI recommend a liver biopsy in patients suspected of having DILI when serology raises the possibility of autoimmune hepatitis, if suspected DILI progresses, or if DILI fails to resolve on withdrawal of the causal agent. More broadly, a liver biopsy may be considered during the investigation of selected patients suspected of suffering from DILI, because liver histology can provide information supporting the diagnosis of DILI or an alternative. As discussed previously, the pattern of liver biopsy may provide diagnostic information by matching known patterns of DILI or by identifying alternative explanations for the injury. The liver biopsy may identify potential etiologies that require additional clinical work-up to exclude. The character and severity of the injury (necrosis, inflammation, and duct loss) may be useful in patient management on a case-by-case basis. Adequacy of the liver biopsy is important, particularly when evaluating bile duct and portal veins. Existing guidelines for adequacy are based on large studies of chronic liver diseases, which have a consistent pattern of injury. In cases of DILI, the condition of the liver is unknown, so the minimum biopsy size should err on the large side: at least 3 cm of tissue core taken with a large needle size (16 gauge).40

SUMMARY

Liver biopsy can be a useful tool in the diagnosis of DILI, particularly in more complex clinical situations or when underlying liver disease is present. Pathologists should carefully evaluate the biopsy to establish the pattern and severity of injury and then correlate these observations with the patient’s history, laboratory tests, and imaging findings. Direct communication with the clinical team can be helpful to clarify the findings and to discuss possible additional clinical evaluation. The final pathology report should include the pathologic findings and clinical-pathologic correlation. The pathologic diagnosis or report discussion should include a comment on the likelihood of a specific drug cause based on the histologic examination. This approach will ensure that the information from the liver biopsy is used to maximum clinical benefit.

KEY POINTS.

Liver biopsy can provide useful information on differential diagnosis and severity of injury in drug-induced liver injury.

Hepatic pathologists are expert consultants able to interpret histologic findings in light of complex clinical information.

The pathologist defines the hepatic pattern of injury, which is closely related to the histologic differential diagnosis.

A liver biopsy may be the only way to diagnose certain injury types, in particular, vascular injury.

The severity and character of the histologic injury may relate to prognosis.

Funding Acknowledgment

This review was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose. Dr D.E. Kleiner and Dr B. Gasmi shared responsibility for preparing and critical review of the article, including all figures and tables.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleiner DE, Gaffey MJ, Sallie R, et al. Histopathologic changes associated with fialuridine hepatotoxicity. Mod Pathol 1997;10(3):192–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenzie R, Fried MW, Sallie R, et al. Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 1995;333(17):1099–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, et al. Hepatic histological findings In suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology 2014;59(2):661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popper H, Rubin E, Cardiol D, et al. Drug-induced liver disease: a penalty for progress. Arch Intern Med 1965;115:128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol 2018;31(6):965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.lacovelli R, Palazzo A, Procopio G, et al. Incidence and relative risk of hepatic toxicity in patients treated with anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors for malignancy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77(6):929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kok B, Lester ELW, Lee WM, et al. Acute liver failure from tumor necrosis factoralpha antagonists: report of four cases and literature review. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63(6):1654–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor SA, Vittorio JM, Martinez M, et al. Anakinra-induced acute liver failure in an adolescent patient with still’s disease. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36(1):e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scully LJ, Clarke D, Barr RJ. Diclofenac induced hepatitis. 3 cases with features of autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1993;38(4):744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleiner DE, Berman D. Pathologic changes in ipilimumab-related hepatitis in patients with metastatic melanoma. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57(8):2233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johncilla M, Misdraji J, Pratt DS, et al. Ipilimumab-associated hepatitis: clinico-pathologlc characterization in a series of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015; 39(8):1075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghabril M, Bonkovsky HL, Kum C, et al. Liver injury from tumor necrosis factoralpha antagonists: analysis of thirty-four cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11(5):558–564 e553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schattner A, Von der Walde J, Kozak N, et al. Nitrofurantoin-induced immunemediated lung and liver disease. Am J Med Sci 1999;317(5):336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, et al. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(1): 103–112 e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black M, Mitchell JR, Zimmerman HJ, et al. Isoniazid-associated hepatitis in 114 patients. Gastroenterology 1975;69(2):289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo MW, Hoofnagle JH, Gu J, et al. Spectrum of statin hepatotoxicity: experience of the drug-induced liver injury network. Hepatology 2014;60(2):679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullick FG, Ishak KG. Hepatic injury associated with diphenylhydantoin therapy. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1980;74(4):442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanderstigel M, Zafrani ES, Lejonc JL, et al. Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome as a cause of hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas. Gastroenterology 1986;90(1): 188–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everett J, Srivastava A, Misdraji J. Fibrin ring granulomas in checkpoint inhibitorinduced hepatitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41(1):134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stolz A, Navarro V, Hayashi PH, et al. Severe and protracted cholestasis in 44 young men taking bodybuilding supplements: assessment of genetic, clinical and chemical risk factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49(9):1195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez MA, Vuppalanchi R, Fontana RJ, et al. Clinical and histologic features of azithromycin-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13(2): 369–76.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Barnhart H, et al. Persistent liver biochemistry abnormalities are more common in older patients and those with cholestatic drug induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110(10):1450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina-Caliz I, Robles-Diaz M, Garcia-Munoz B, et al. Definition and risk factors for chronicity following acute idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2016;65(3):532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruno S, Maisonneuve P, Castellana P, et al. Incidence and risk factors for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: prospective study of 5408 women enrolled in Italian tamoxifen chemoprevention trial. BMJ 2005;330(7497):932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori S, Arima N, Ito M, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-like pattern in liver biopsy of rheumatoid arthritis patients with persistent transaminitis during low-dose methotrexate treatment. PLoS One 2018;13(8):e0203084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begriche K, Massart J, Robin MA, et al. Drug-induced toxicity on mitochondria and lipid metabolism: mechanistic diversity and deleterious consequences for the liver. J Hepatol 2011;54(4):773–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starko KM, Mullick FG. Hepatic and cerebral pathology findings in children with fatal salicylate intoxication: further evidence for a causal relation between salicylate and Reye’s syndrome. Lancet 1983;1(8320):326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fromenty B, Fisch C, Labbe G, et al. Amiodarone inhibits the mitochondrial betaoxidation of fatty acids and produces microvesicular steatosis of the liver in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990;255(3):1371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Bus L, Depuydt P, Libbrecht L, et al. Severe drug-induced liver injury associated with prolonged use of linezolid. J Med Toxicol 2010;6(3):322–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheffner D, Konig S, Rauterberg-Ruland I, et al. Fatal liver failure in 16 children with valproate therapy. Epilepsia 1988;29(5):530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nalbantoglu IL, Tan BR Jr, Linehan DC, et al. Histological features and severity of oxaliplatin-induced liver injury and clinical associations. J Dig Dis 2014;15(10): 553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geller SA, Dubinsky MC, Poordad FF, et al. Early hepatic nodular hyperplasia and submicroscopic fibrosis associated with 6-thioguanine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28(9):1204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czeczok TW, Van Arnam JS, Wood LD, et al. The almost-normal liver biopsy: presentation, clinical associations, and outcome. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41(9):1247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutherford A, King LY, Hynan LS, et al. Development of an accurate index for predicting outcomes of patients with acute liver failure. Gastroenterology 2012; 143(5):1237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjornsson E, Kalaitzakis E, Olsson R. The impact of eosinophilia and hepatic necrosis on prognosis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25(12):1411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ndekwe P, Ghabril MS, Zang Y, et al. Substantial hepatic necrosis is prognostic in fulminant liver failure. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23(23):4303–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonkovsky HL, Kleiner DE, Gu J, et al. Clinical presentations and outcomes of bile duct loss caused by drugs and herbal and dietary supplements. Hepatology 2017;65(4):1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Church RJ, Kullak-Ublick GA, Aubrecht J, et al. Candidate biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of drug-induced liver injury: an international collaborative effort. Hepatology 2019;69(2):760–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. , American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 2009;49(3):1017–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2019;70(6):1222–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]