Abstract

Purpose of the review

Microvascular ischemic disease of the brain is a common cause of cognitive impairment and dementia, particularly in the context of preexisting cardiovascular risk factors and aging. This review summarizes our current understanding of the emerging molecular themes that underlie progressive and irreparable vascular pathology leading to neuronal tissue injury and dementia.

Recent findings

Cardiometabolic risk factors including diabetes and hypertension are known to contribute to vascular pathology. Currently the impact of these risk factors on the integrity and function of the brain vasculature has been target of intense investigation. Molecularly, the consequences associated with these risk factors indicate that reactive oxygen species are strong contributors to cerebrovascular dysfunction and injury. In addition, genetic linkage analyses have identified penetrant monogenic causes of vascular dementia. Finally, recent reports begun to uncover a large number of polymorphisms associated with a higher risk for cerebrovascular disease.

Summary

A comprehensive picture of key risk factors and genetic predispositions that contribute to brain microvascular disease and result in vascular dementia is starting to emerge. Understanding their relationships and cross-interactions will significantly aid in the development of preventive and intervention strategies for this devastating condition.

Keywords: cerebrovascular disease, cognitive impairment, neuronal degeneration, small vessel disease, vascular dementia

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is characterized by progressive decline in cognitive ability leading to impaired autonomy of function. Dementia has become a serious public health problem given its profound impact to individuals, families and society at large. This problem is significantly amplified by an increasingly aging population, and the soaring prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Thus, a clear mechanistic understanding of predisposing conditions, biomarkers for prognosis, and molecular drivers of dementia has become of paramount importance.

Neuronal dysfunction and degeneration, such as the one resulting from the accumulation of beta-amyloid protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease constitute the major cause for dementia, accounting for 60–70% of the cases. Nonetheless, the realization that vascular pathology alone or in conjunction with other causes of neurodegeneration contributes substantially to dementia has expanded an interest in understanding vascular brain health [1].

Vascular dementia is the second most common form of dementia. Unfortunately, it is generally underrecognized and poorly understood [1]. Much like Alzheimer’s disease, vascular pathology in the brain impairs higher cortical processes including reasoning, planning and memory as reduced cerebral blood flow leads to secondary focal neuronal injury with irreversible tissue loss. While it has been estimated that vascular cause of dementia constitutes up to 20% of cases in the elderly, the inconspicuous nature of the symptoms and the common coexistence of vascular pathology with other neurodegenerative processes, would suggest that the true contribution of vascular mechanisms to dementia is likely to be significantly higher [2,3].

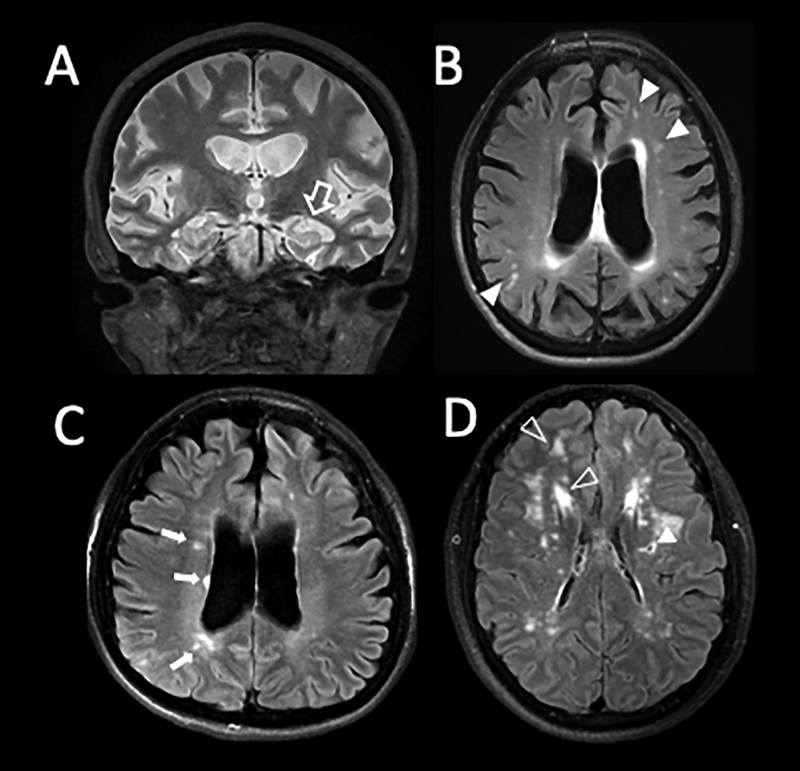

In the clinic, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain provides detailed in-vivo imaging of the progressive changes associated with neurological disorders, cognitive decline and dementia. This technology shows brain volume loss as the ultimate outcome of seemingly different pathophysiological processes (Figure 1:A–D). To date MRI remains the most effective form for diagnosis and non-invasive tool to assess disease progression, but it does not identify causation and it is unable to pint-point molecular mechanisms for the disease.

Figure 1: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a tool to diagnose neuronal disease.

A: Coronal T2 weighted image of 55-year-old woman with substantial hippocampal atrophy (open arrow) and volume loss consistent with Alzheimer’s disease. B: Axial FLAIR T2 image of the same patient illustrating coexisting microvascular ischemic changes (filled arrow heads). C: Axial FLAIR T2 in a 32-year-old patient with Advanced Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Note the orientation of the white matter lesions nearly touching ventricular surface (small arrows). This patient too has volume loss as indicated by her enlarged ventricular system and cortical atrophy. D: FLAIR T2 images in a young CADASIL patient with minimal deficits. Filled arrow head shows gliosis around a prior small lacunar stroke. Open arrow heads show prominent multifocal areas of white matter hyperintensity typical for CADASIL.

Microvascular ischemic disease of the brain contributing to dementia most commonly represents a complex disorder that emerges over decades from the convergence of multiple factors disrupting vessel physiology and integrity ultimately resulting in neuronal injury. Highly penetrant monogenic forms of microvascular ischemic disease of the brain leading to vascular dementia have been recently identified. These disorders constitute important models to understand the sensitive relationship between vascular and neuronal health.

Here we examine the recent developments on our understanding of the genetic and predisposing risk factors associated with vascular dementia with a focus on molecular mechanisms.

Monogenic causes of vascular dementia

While most of the literature stresses the contribution of cardiometabolic risk factors and age as key determinants of vascular dementia, several monogenic diseases lead to a phenotype of early-onset cerebrovascular disease. These findings strongly argue for the key role of genetics as a potential independent cause for the condition.

Monogenic causes that could lead to vascular dementia include mutations in NOTCH3 (CADASIL), HTRA1 (CARASIL), COL4A1/COL4A2 (small vessel arteriopathy and cerebral hemorrhage), TREX1 (Cerebro-Retinal vasculopathy) and GLA (Fabry disease) (Table 1).

Table I –

Monogenic causes of vascular dementia

| DISEASE | GENE | KNOWN or PROPOSED PROPOSED FUNCTION |

|---|---|---|

| CADASIL | NOTCH3 | Receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells |

| CARASIL | HTRA1 | Serine peptidase that degrades extracellular matrix |

| SVACH | COL4A1 | Structural component of the basement membrane |

| RVCL | TREX1 | Exonuclease that degrades DS-DNA |

| Fabry | GLA | Degradation of glycosphingolipids |

CADASIL - cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

CARASIL - cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

SVACH - retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy

RVCL - retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy

The most common form of monogenic hereditary vasculopathy associated with dementia is: cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) [4*]. Patients with this disease often become symptomatic in the second to fourth decade of life with complex migraine phenomena and strokes. Because of the brain MRI appearance (Figure 1) and their relative young age, patients with CADASIL are often misdiagnosed as suffering Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

CADASIL is associated with progressive degeneration of vascular smooth muscle cells in small and medium-size arteries. The cellular and molecular alterations affect vascular contractility, impair barrier function and promote vascular fragility [5–7]. Despite of the fact that these changes are systemic in nature, the disorder is clinically manifested in the brain leading, over several decades, to multifocal ischemia with progressive impairment of cognitive function [8].

CADASIL is caused from mutations in the NOTCH3 gene [9] which codes for a receptor with predominant expression in arterial smooth muscle cells. NOTCH3 regulates multiple aspects of vascular homeostasis, including tone, vascular tension, and endothelial health [10]. This receptor is a complex protein with a large extracellular domain containing multiple endothelial growth factor (EGF)-like repeats and a small transmembrane and intracellular portion. CADASIL disease-causing mutations occur in the extracellular domain of the receptor. While the genetic cause of CADASIL has been known for 20 years, understanding how NOTCH3 dysfunction lead to the disease is still limited. This is partially due to the wide genetic diversity of mutations and the incomplete understanding of NOTCH3 function in blood vessels. In this issue, Ferrante and colleagues specifically focus on the clinical and cellular aspects of the disease (Ferrante et al., in this issue).

A second monogenic cerebrovascular disease similar to CADASIL in symptoms and in MRI presentation has been recently identified and linked to HTRA1 (HtrA serine peptidase 1). The pathology was named CARASIL for cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy [11,12]. HTRA1 codes for a serine protease with broad target specificity. Some of its substrates include extracellular matrix proteins, proteoglycans, and growth factor-binding proteins. Through its ability to target proteoglycans, HRTA1 controls the release of FGF and it also regulates the availability of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), as per its ability to cleave IGF-binding proteins. As CADASIL, CARASIL affects vascular smooth muscle cells and it is systemic in nature, but symptoms are more severely manifested in the brain likely due to this organ’s sensitivity to changes in oxygen levels. Precise information as to the molecular consequences of HTRA1 mutations in smooth muscle cells remain unclear. Recently, heterozygous mutations in the HTRA1 gene have been also associated with microvascular disease of the brain in older individuals, suggesting high sensitivity to protein levels [13].

As an abundant component of basement membranes, type IV collagen is critical in maintaining vascular integrity. Thus, it is not surprising that mutations in the COL4A1 and A2 genes has been linked to small vessel arteriopathy and cerebral hemorrhages [14]. Just like the two previous syndromes, this arteriopathy is systemic, however the brain’s low tolerance for microhemorrhages makes this organ more sensitive to pathologies which result in significant leukoencephalopathy and dementia.

Mutations in TREX1 have been associated with retinal vasculopathy and cerebral leukodystrophy (RVCL) [20]. Symptoms for this disorder start in adulthood and frequently include rapid loss of vision, multifocal strokes and dementia. The mechanisms involved in this disease are unclear, as it is the role of TREX1 in vascular homeostasis. Interestingly, TREX1 codes for an exonuclease that degrades double stranded DNA. It has been proposed that degradation of double stranded DNA by TREX1 prevent this polynucleotide from acting as an autoantigen to inappropriately activate the immune system. Mutations in TREX1 are also is responsible for several interferon-mediated autoinflammatory diseases including chilblain lupus and Aicardi-Goutières syndrome type-1.

Absent or markedly reduced activity of the alpha-galactosidase enzyme (GLA gene) results in Fabry disease, an X-Linked lysosomal storage disorder. This disorder is characterized by the accumulation of globotriaoslyceramide and related glycosphingolipids in plasma and lysosomes of blood vessels, nerves, and other organs [15]. This abnormal accumulation of glycosphingolipids yields cerebrovascular disease and neuropathy in addition to renal failure, cardiac disease, and skin manifestations [16]. Stroke or transient ischemic attacks occur in about 11% of the patients and these subsequently lead to vascular dementia [17].

Polymorphisms and vascular dementia

Besides the monogenic causes of vascular dementia discussed above, multiple risk-alleles associated with microvascular ischemic disease of the brain have been recently identified. Here we highlight polymorphisms in genes expressed by vascular cells and that were found in at least two independent studies.

The structural integrity of the vascular endothelium relies on junctional proteins. Brain vessels, in particular, express high levels of claudins which contribute to form the blood brain barrier. Claudins play an important role in organizing tight junctions between endothelial cells. Polymorphisms of CLDN1 (claudin1) were recently associated with small vessel vascular dementia [18]. Further supporting a previous study indicating that claudin expression profile alone was able to segregate Alzheimer’s disease cases from normal aging and from vascular dementia patients [19]. Given their critical role to promote vascular integrity, it is likely that more polymorphisms and/or mutations in structural junctional proteins will continue to emerge as genetic risk factors.

Perhaps not surprising, some variants associated with systemic vascular disease were also associated with cerebrovascular disease. One of the risk-alleles identified by GWAS for vascular dementia was APOE (apolipoprotein E), which codes for a protein involved in lipid metabolism. This association has been reported by several studies including one with more than 10,000 subjects [21,22]. Another, lipid-related gene, PON1 (paraoxonase 1) was also associated with a higher risk of vascular dementia [23]. Paraoxonase 1 is an enzyme with lactonase and ester hydrolase activity which in the circulation binds to high density lipoprotein and is responsible for the hydrolysis of xenobiotics. Polymorphisms in this gene also cause atherosclerosis and diabetic retinopathy. In addition, polymorphisms in regulatory proteins associated with inflammation, such as TNF-alpha [24] and TGF-beta1 [25] were also found to be highly correlated with vascular dementia.

While not exclusively associated with vascular brain disease, polymorphisms in several other genes have been identified by GWAS. Figure 2 highlights genes that were independently identified in at least two studies. These include: TSPAN2, PITX2, ZFHX3, ADAMTS2, RIM29, LSLR, SMARCA4, PTPRF, FGA, FOXF2, CDK6, TWIST1, MMP12, WNT2B, NEDD4, ZFHX3, CLDN17, ATG7, KNG1, and CACNB2 [26–32*]. Of note: HDAC9 was associated with large artery atherosclerosis stroke and ALDH2 with small artery stroke.

Figure 2: Risk factors and Predispositions in Vascular Dementia.

Four major factors are associated with vascular dementia: (1) Stroke, both hemorrhagic or embolic has been recognized as a strong predisposing factor for vascular dementia; (2) Disease risk factors, particularly hypertension and diabetes are significantly associated with vascular dementia. Mechanistically, both conditions appear to promote vascular injury through increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS); (3) Several deleterious mutations in the listed genes have been identified as monogenic cause of vascular dementia; (4) Extensive GWAS studies have identified a number of polymorphisms in several genes (as listed) that are associated with vascular disease.

As for genetic modifiers, limited clinical reports have identified concurrent mutations in CADASIL patients that may contribute to early disease progression. These include: Factor V Leiden and MTHFR [33].

Brain ischemic and hemorrhagic events: A path to vascular dementia

According to many epidemiological studies, dementia occurs in one third of stroke victims and a previous stroke doubles the risk of dementia compared to age-and sex-matched controls. During the first-year post-stroke there is a nine-fold excess risk of dementia that only gets reduced to four-fold risk thereafter [34]. In fact, a major long-term consequence of stroke is cognitive and functional deficit and incidence of stroke impairs cognitive function regardless of race or ethnicity [35].

Strokes emerge as localized, focal events at the level of the microcirculation due to underlying genetic, cardiometabolic and / or other predisposing factors [36*] (Figure 2). Embolic strokes have the implication of a proximal source of embolism (often the heart chambers of valves, or large extra or -intracranial vessels) that release cloth fragments to more distant branches of the vascular network lodging in smaller portions of the vascular tree with ensuing ischemia. Strokes could also emerge from disruptions of the vascular wall. Often, injury to the vascular tissue results in extravasation of blood components which under some circumstances, such as uncontrolled hypertension, might evolve into life threatening intracranial hematomas.

Risk Factors Associated with Stroke and Dementia

Adverse cardiometabolic profiles have been associated with cerebrovascular alterations. In some cases, these factors predispose to what is called silent infarcts, which lack stroke-like symptoms, but are found by neuroimaging or upon necropsy. These silent infarcts promote subclinical changes that are thought to progressively underlie vascular dementia as well as cognitive and functional decline. While functional decline can be view as consequence of aging, systemic burden associated particularly with diabetes and hypertension clearly accelerates deficits. These factors promote constant and irreparable “wearing” of the cerebral vasculature, a premature form of vascular aging. Below we discuss the key risk factors identified with vascular dementia and their underlying molecular mechanisms.

Diabetes – Several epidemiological studies have associated prevalence of diabetes with stroke, particularly small artery disease (lacunar stroke), stroke recurrence and stroke mortality [37]. In fact, glycemic index from nearly 3,000 patients was independently associated with impaired endothelial function and severity of the stroke [38*]. At the molecular level, alterations in circulating glucose affect levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that promote oxidative stress [39*]. While low levels of ROS can be beneficial to cellular physiology, high and constant ROS can impair mitochondrial function, promote hypoxia, and even cell death [40]. Imbalance in ROS has been directly associated with the pathogenesis of dementia [41]. Specifically, patients with vascular dementia have high levels of plasma lipid peroxidation [42], reduced plasma antioxidant levels [43] and increased DNA oxidation in their cerebrospinal fluid [44]. While one could claim that the findings are correlative, as measurements of ROS are indirect and obtained from the circulation, evidence that ROS is an important underlying mechanism has been further supported by direct inhibition of adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX). NOX is the major source of ROS in endothelial cells [45] and its inhibition attenuated chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in mouse models [46].

Hypertension – Hypertension emerges as the largest contributor to the overall societal burden of stroke. Approximately 40% of first-time strokes in their 50s and 60s are attributable to hypertension [47]. Furthermore, recent meta-analysis studies demonstrated that adherence to antihypertensive medications strongly reduced stroke risk in hypertensive patients [48*]. Here once again, ROS might be an important molecular mechanism. Angiotensin II (AngII) is a critical mediator of hypertension and it has been shown to promote vascular disease through several mechanisms that also converge on the increase ROS levels resulting in endothelial damage and dysfunction [49,50]. Molecularly, AngII directly stimulates NOX1 and NOX2 in vascular cells [51,52]. Furthermore, it is well accepted that AngII regulation of NOX1 and NOX2 affect hypertrophy in smooth muscle cells[53,54], and therefore it critical to vascular contractility (and hypertension).

Hypercholesterolemia – While familial hypercholesterolemia did not confer an increased risk of ischemic stroke [55*], more than half of stroke patients had elevated cholesterol levels and variants in PCSK9 that reduce cholesterol were found to be protective against ischemic stroke [56*]. These two recent studies seem to be at odds with one another, clearly more investigations are necessary. Imporrtantly, at the molecular level, and similar to diabetes, hypercholesterolemia can also lead to increase in ROS contributing to vascular wall wearing [57].

A common underlying mechanism of the most important risk factors in stroke and vascular dementia appears to be reactive oxygen species and NOX. Further supporting this concept, inactivation of NOX2 in mice completely eliminates the functional hyperemia and pathological changes in cerebral blood vessels [58,59]. Moreover, a pharmacological inhibitor of NOX oxidase blocked generation of ROS and prevented cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by AngII [60,61]. Clearly, experimental evidence is strong and progression to the clinic, particularly in relation to hypertension patients should be a priority.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant contributors to morbidity and disability in aging populations are cerebrovascular disease associated with dementia. While vascular abnormalities are intimately linked with progressive deterioration in the health status of the brain, large fractions of the underlying pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms are unknown. Robust data on epidemiologic, genetic and causal associations are progressively uncovering genetic predispositions, but generation of specific animal models and pre-clinical studies are critical to further validate the findings.

Research focus would benefit from combinatorial studies which take into account already identified cardiometabolic factors with genetic risks. Major obstacles relate to the heterogeneity of the disease, its slow progression, and the challenge of integrating vascular microenvironment with genetics. A clear understanding of the molecular wiring of brain endothelial and smooth muscle cells and their unique transcriptional make-up will expand our ability to identify factors that might be of more specific relevance to the brain. Through the rapid advances in single cell RNA transcriptomics this is rapidly becoming a reality [62**]. Such information will expand our ability to systematically integrate risk factors and genetics using more clear outcomes and molecular read-outs.

KEY POINTS.

Cerebrovascular alterations have been recently recognized as significant causes of dementia, only second to Alzeimer’s disease.

Several monogenic and polygenic causes for vascular dementia target genes that regulate smooth muscle cell contractility, association of vascular cells with the extracellular matrix, and response to growth factors.

In addition to hereditary conditions, systemic burden associated with diabetes and hypertension are strong contributing factors in cerebrovascular disease.

At the molecular level, several of these risk factors produce an imbalance between production and removal of ROS by antioxidant species that has been linked to the pathogenesis of dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members of the Arispe lab and the CADASIL group at the National Institutes of Health for the vigorous discussions, and apologize in advance for work not cited due to space constraints.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP:

This work was supported by a grant from the National Health Institute U01HL31019.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the 18 months (2017–2018), have been highlighted as:

*of special interest

**of outstanding interest

- 1.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013; 80:844–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Riordan S, Nor AM, Hutchinson M. CADASIL imitating multiple sclerosis: the importance of MRI markers. Mult Scler 2002; 8:430–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey T, Abubacker S. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: an imaging mimic of multiple sclerosis. A report of two cases. Med Princ Pract 2006; 15:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. *.Di Donato I, Bianchi S, De Stefano N, et al. Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) as a model of small vessel disease: update on clinical, diagnostic, and management aspects. BMC Med 2017; 15:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides a recent and comprehensive summary of the clinical and cellular changes associated with CADASIL.

- 5.Oh SI, Kim SH, Kim HJ. Massive pontine microbleeds in a patient with CADASIL. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71:1048–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dichgans M, Holtmannspotter M, Herzog J, et al. Cerebral microbleeds in CADASIL: a gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging and autopsy study. Stroke 2002; 33:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werbrouck BF, De Bleecker JL. Intracerebral haemorrhage in CADASIL. A case report. Acta Neurol Belg 2006; 106:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JC. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: a genetic cause of cerebral small vessel disease. J Clin Neurol 2010; 6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature 1996; 383:707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T, Baron M, Trump D. An overview of Notch3 function in vascular smooth muscle cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2008; 96:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukutake T. Cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CARASIL): from discovery to gene identification. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2011; 20:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nozaki H, Nishizawa M, Onodera O. Features of cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke 2014; 45:3447–3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdura E, Herve D, Scharrer E, et al. Heterozygous HTRA1 mutations are associated with autosomal dominant cerebral small vessel disease. Brain 2015; 138:2347–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanfranconi S, Markus HS. COL4A1 Mutations as a Monogenic Cause of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease A Systematic Review. Stroke 2010; 41:E513–E518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pastores GM, Liew YHH. Biochemical and molecular genetic basis of Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:S130–S133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiffmann R. Fabry disease. Pharmacol Therapeut 2009; 122:65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi QY, Chen JJ, Pongmoragot J, et al. Prevalence of Fabry Disease in Stroke Patients-A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc 2014; 23:985–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivasan V, Braidy N, Xu YH, et al. Association of genetic polymorphisms of claudin-1 with small vessel vascular dementia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2017; 44:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spulber S, Bogdanovic N, Romanitan MO, et al. Claudin expression profile separates Alzheimer’s disease cases from normal aging and from vascular dementia cases. J Neurol Sci 2012; 322:184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards A, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, Jen JC, et al. C-terminal truncations in human 3 ‘−5 ‘ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause autosomal dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy. Nature Genetics 2007; 39:1068–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi XW, Xu LQ, Hiller S, Kim HS, Maeda N. Reduced alpha-lipoic acid synthase gene expression exacerbates atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223(1):137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skrobot OA, McKnight AJ, Passmore PA, et al. A Validation Study of Vascular Cognitive Impairment Genetics Meta-Analysis Findings in an Independent Collaborative Cohort. Journal of Alzheimers Disease 2016; 53:981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helbecque N, Cottel D, Codron V, et al. Paraoxonase 1 gene polymorphisms and dementia in humans. Neurosci Lett 2004; 358:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCusker SM, Curran MD, Dynan KB, et al. Association between polymorphism in regulatory region of gene encoding tumour necrosis factor alpha and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: a case-control study. Lancet 2001; 357:436–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peila R, Yucesoy B, White LR, et al. A TGF-beta 1 polymorphism association with dementia and neuropathologies: The HAAS. Neurobiol Aging 2007; 28:1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traylor M, Zhang CR, Adib-Samii P, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of cerebral white matter hyperintensities in patients with stroke. Neurology 2016; 86:146–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arning A, Hiersche M, Witten A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a gene network of ADAMTS genes in the predisposition to pediatric stroke. Blood 2012; 120:5231–5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carty CL, Keene KL, Cheng YC, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies genetic risk factors for stroke in African Americans. Stroke 2015; 46:2063–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. *.Lee TH, Ko TM, Chen CH, et al. A genome-wide association study links small-vessel ischemic stroke to autophagy. Sci Rep 2017; 7:15229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Interesting study that demonstrates an association between ischemic stroke and ATG7 by GWAS.

- 30.Dichgans M, Malik R, Konig IR, et al. Shared genetic susceptibility to ischemic stroke and coronary artery disease: a genome-wide analysis of common variants. Stroke 2014; 45:24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Network NSG, International Stroke Genetics C. Loci associated with ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (SiGN): a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. **.Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat Genet 2018; 50:524–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Impressive study that identified 32 stroke risk loci by performing genome-wide association meta-analysis in more than 500,000 individuals.

- 33.Mandellos D, Limbitaki G, Papadimitriou A, Anastasopoulos D. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) in a Greek family. Neurol Sci 2005; 26:278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pendlebury ST. Dementia in patients hospitalized with stroke: rates, time course, and clinico-pathologic factors. Int J Stroke 2012; 7:570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine DA, Kabeto M, Langa KM, et al. Does stroke contribute to racial differences in cognitive decline? Stroke. 2015; 46:1897–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. *.Gupta A, Giambrone AE, Gialdini G, et al. Silent brain infarction and risk of future stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2016; 47:719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive review that provides important compilation of evidence that silent brain infarcts are a common occurrence in the general population and are associated with a two-fold increase of future stroke

- 37.Gezmu T, Schneider D, Demissie K, et al. Risk factors for acute stroke among South Asians compared to other racial/ethnic groups. PLoS One 2014; 9:e108901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. *.Lee KJ, Lee JS, Jung KH. Interactive effect of acute and chronic glycemic indexes for severity in acute ischemic stroke patients. BMC Neurol 2018; 18:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates a clear association between glycemic index and strokes. It also identifies HbA1c as a potential modifier.

- 39. *.Warren CM, Ziyad S, Briot A, et al. A ligand-independent VEGFR2 signaling pathway limits angiogenic responses in diabetes. Sci Signal 2014; 7:ra1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work provides evidence that excessive and long-term ROS from hyperglycemia in the endothelium affects levels of VEGFR2 at the cell surface.

- 40.Venkat P, Chopp M, Chen J. Models and mechanisms of vascular dementia. Exp Neurol 2015; 272:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett S, Grant MM, Aldred S. Oxidative stress in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a common pathology. J Alzheimers Dis 2009; 17:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gustaw-Rothenberg K, Kowalczuk K, Stryjecka-Zimmer M. Lipids’ peroxidation markers in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2010; 10:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polidori MC, Mattioli P, Aldred S, et al. Plasma antioxidant status, immunoglobulin g oxidation and lipid peroxidation in demented patients: relevance to Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004; 18:265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gackowski D, Rozalski R, Siomek A, et al. Oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage is characteristic for mixed Alzheimer disease/vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 2008; 266:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, Sobey CG. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10:453–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi DH, Lee KH, Kim JH, et al. NADPH oxidase 1, a novel molecular source of ROS in hippocampal neuronal death in vascular dementia. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 21:533–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whisnant JP, Wiebers DO, O’Fallon WM, et al. A population-based model of risk factors for ischemic stroke: Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology 1996; 47:1420–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. *.Xu T, Yu X, Ou S, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medications and stroke risk: a dose-response meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6:e006371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This evaluation that included 18 studies and over 1 million patients determined that adherence to anti-hypertension medication was highly associated with a lower risk of stroke.

- 49.Gray SP, Jandeleit-Dahm KAM. The Role of NADPH oxidase in vascular disease - hypertension, atherosclerosis & stroke. Curr Pharm Design 2015; 21:5933–5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chrissobolis S, Banfi B, Sobey CG, Faraci FM. Role of Nox isoforms in angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in brain. J Appl Physiol 2012; 113:184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chabrashvili T, Kitiyakara C, Blau J, et al. Effects of ANG II type 1 and 2 receptors on oxidative stress, renal NADPH oxidase, and SOD expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2003; 285:R117–R124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuno K, Yamada H, Iwata K, et al. Nox1 is involved in angiotensin II-mediated hypertension – a study in Nox1-deficient mice. Circulation 2005; 112:2677–2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin-Ii stimulates Nadh and Nadph oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth-muscle cells. Circ Res 1994; 74:1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ushio-Fukai M, Zafari AM, Fukui T, et al. p22phox is a critical component of the superoxide-generating NADH/NADPH oxidase system and regulates angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:23317–23321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. *.Beheshti S, Madsen CM, Varbo A, et al. Relationship of familial hypercholesterolemia and high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to ischemic stroke. Circulation 2018; 138:578–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehesive study that examines risk of stroke in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia and high LDL cholesterol. Surprisingly it was found that high cholesterol did not confer an increased risk of ischemic stroke.

- 56. *.Rao AS, Lindholm D, Rivas MA, et al. Large-scale phenome-wide association study of pcsk9 variants demonstrates protection against ischemic stroke. Circ Genom Precis Med 2018; 11:e002162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evaluation of more than 300,000 individuals with PCSK9 missense variants demonstrated protective effect of PCSK9 inhibition and protection against stroke.

- 57.Dias IH, Polidori MC, Griffiths HR. Hypercholesterolaemia-induced oxidative stress at the blood-brain barrier. Biochem Soc Trans 2014; 42:1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farkas E, Luiten PG. Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 2001; 64:575–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Girouard H, Park L, Anrather J, et al. Angiotensin II attenuates endothelium-dependent responses in the cerebral microcirculation through nox-2-derived radicals. Arterioscler Vasc Biol 2006; 26:826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Didion SP, Faraci FM. Angiotensin II produces superoxide-mediated impairment of endothelial function in cerebral arterioles. Stroke 2003; 34:2038–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab 2008; 7:476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. **.Vanlandewijck M, He L, Mae MA, et al. A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature 2018; 554:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study that provides single cell transcriptomics on the vasculature of the brain. It identifies specific endothelial, smooth muscle and pericyte cell types and highlights a progressive zonation (transcriptional transition) in cell subtypes.