Abstract

Complex intra-fractional motion and deformation of the liver significantly impacts the accuracy of delivered dose in radiotherapy, and limits margin reduction, dose escalation and normal tissue sparing. A critical component of motion management is to accurately reconstruct tumor motion. In this study, we developed a Six Degree of Freedom Projection Marker Matching method (6-DoF PM3) to reconstruct translational and rotational liver tumor motion in a rotational treatment delivery, such as volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). Specifically, we modeled the use of two gold markers implanted in a linear form. The four endpoints of the two gold linear markers were used as tracking surrogates. During delivery, kV x-ray projection images were acquired. A method was developed to automatically identify the 2D marker-endpoints on the projection images. 3D marker positions were determined by solving an optimization problem with the objective function penalizing the distance from the reconstructed 3D position of each fiducial marker endpoint to the corresponding straight line defined by the kV x-ray projection of the endpoints. We performed a series of tests to evaluate different components of the method. For 2D marker endpoints identification, 99.9% of the marker endpoints were identified with an error ≤0.338 mm (1 pixel) along both u and v directions. For 3D reconstruction of motion in simulation studies, error of rotational angle was (0.5 ± 6.5) × 10−3 degree without considering the 2D marker identification error. The rotational angle error was relatively sensitive to the accuracy of 2D marker identification. When the error raised from 0.22mm to 0.776 mm, the error of 3D rotational angle increased from 0.5 degree to 2.5 degree. In the experimental end-to-end tests, the mean root-mean square error of the 3D reconstructed marker positions was 0.75 mm and the mean error of rotational angle was within 1.7°. Our method can accurately determine intra-fractional liver tumor motion in rotational radiotherapy using kV projections of only two linear fiducial markers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy, particularly stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has demonstrated its potency in eradicating liver tumors noninvasively (Schefter et al., 2005; Kavanagh et al., 2006; Andratschke et al., 2009; Arcangeli et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2015). However, intra-fractional motion resulting from respiration is a concern, limiting margin reduction and therefore, dose escalation and normal tissue sparing. Liver tumor motion may have complex patterns. A recent study found that the motion contains both translational and rotational components with the mean translational and rotational range (2nd-98th percentile) being 2.0 mm/3.9° (right-left), 9.2 mm/2.9° (superior-inferior), and 4.0 mm/4.0° (anterior-posterior) even under abdominal compression (Bertholet et al., 2016). The complex motion causes significant deviation of delivered dose from the well planned dose, especially in the region with a rapid dose fall-off (Shirato et al., 2004; Park et al., 2012). It has been reported that intra-fractional liver motion leads to 6% reduction of the mean D95% of the target (maximum dose covering at least 95% of the volume) with a mean 3D target position error of 2.9 mm (Poulsen et al., 2014). The complexity of tumor motion and its impact on the accuracy of delivered dose, as well as its hindrance on margin reduction and normal tissue sparing, have created a substantial need for more patient-specific, advanced and effective motion management strategies.

One important aspect for a successful motion management strategy is precisely knowing intra-fractional tumor motion trajectory. Not only is the trajectory information helpful by providing valuable data regarding tumor motion characteristics, it is also the basis of many other motion management techniques, such as multi-leaf collimator tracking (Sawant et al., 2008; Sawant et al., 2009; Keall et al., 2014; Lu, 2008; Lu et al., 2009). Over the years, several approaches have been developed to quantify and adapt to intra-fractional liver motion trajectory, such as radiofrequency or optical tracking, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound based approaches, and kV (kilovoltage)/MV (megavoltage) imaging based approaches (Bertholet et al., 2019). A representative system belonging to the radiofrequency tracking based approaches is Calypso system (Calypso Medical Technologies, Seattle, WA), which has been applied for respiratory gating in liver SBRT (Smith et al., 2009; Poulsen et al., 2015). However, its clinical application is impeded by several limitations such as compromised tracking accuracy caused by magnetic field distortion, required additional hardware supports, subsequent severe image artifacts in MRI that hinder response assessment, etc. (Franz et al., 2014). In addition, Calypso has a limited sensitive volume, which may be a problem for tracking liver tumor motions in large patients. In the MRI based approaches, along with the rapid technological development of MR-linac (integrated MRI and linear accelerator) in recent years, MRI-guided real time monitoring and gating for abdomen tumor treatment has been reported from clinical practice (Henke et al., 2018; Green et al., 2018; Tetar et al., 2018). However, several concerns may hinder the clinical widespread utilization of this new technique in near future. For example, the significantly prolonged treatment time, noise, sensation of heat, etc., due to the introduction of MRI to the treatment delivery, can be problematic or intolerable for some of the patients. Besides, it can be prohibitively expensive for integration in most clinics. MV/kV x-ray projection images have also been employed to track tumor motion (Kitamura et al., 2003; Shirato et al., 2004; Kirilova et al., 2008; Worm et al., 2013; Poulsen et al., 2014; Bertholet et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017). The MV-based methods use an Electronic Portal Imaging Device to acquire real time projection images formed by the therapeutic beam. The use of multi-leaf collimator for intensity modulation, however, may block field of view. In contrast, using the kV imaging system mounted on a LINAC has certain advantages. A probability-based Kilovoltage Intrafraction Monitoring (KIM) system have been successfully developed to reconstruct the 3D marker trajectory in liver SBRT (Poulsen et al., 2014).

In this paper, we present a novel approach to derive the rigid rotation and translation of the liver tumor motion by reconstructing the marker trajectories using kV projection images acquired during a rotational radiotherapy delivery, such as Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). Specifically, we proposed to implant two linear markers inside the patient liver site before treatment. During a treatment delivery, the triggered kV imaging function on a TrueBeam LINAC (Varian Medical System, Palo Alto, CA) was used to acquire projection images. In each projection image, four endpoints of the two markers were identified. We extended the Projection Marker Matching Method (PM3), which was previously developed by our group to reconstruct 3D intra-fractional translational motion (Chi et al., 2017), to enable the calculations of the rotational components, therefore enabling 6 degree-of-freedom (DoF) motion tracking. Compared to existing methods for 6 DoF motion reconstruction, the contribution of this work is twofold. First, we used four endpoints from two linear markers as surrogates to track the 6 DoF liver motion, instead of using three or more markers. The method is unique that four points are sufficient for 6 DoF motion reconstruction while using only two markers is expected to reduce the complication caused by marker implantation. It is reported that the risk of complications such as bleeding or infection (Kirilova et al., 2008), increases with the number of inserted markers. Second, our study determined the 6-DoF motion directly from measured x-ray projections, which is a direct 2D-to-6D prediction. This idea was motivated by recent advances in 2D-3D image registration problems, where motion in the 3D space can be accurately determined by 2D projection images based on projection geometry via optimization approaches (Otake et al., 2015; Uneri et al., 2015; De Silva et al., 2016). In comparison, in the existing 2D-to-6D motion reconstruction methods such as 6-DoF KIM (Tehrani et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017), the trajectory of each marker was first estimated from a probability-based method and the 6-DoF motion was obtained by analyzing trajectories of multiple markers. The main limitation of this method is that the trajectory prediction errors for any of the markers in the first step could affect the motion reconstruction accuracy in the second step, especially for the rotational components. In the other method (Nguyen et al., 2017), a linear correlation between the translational motion along the superior-inferior direction and the motions in the rest 5 DoF was assumed to predict the 6 DoF motion from the 2D kV projections. The accuracy may be a concern when the correlation is not strong enough (Nguyen et al., 2017).

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

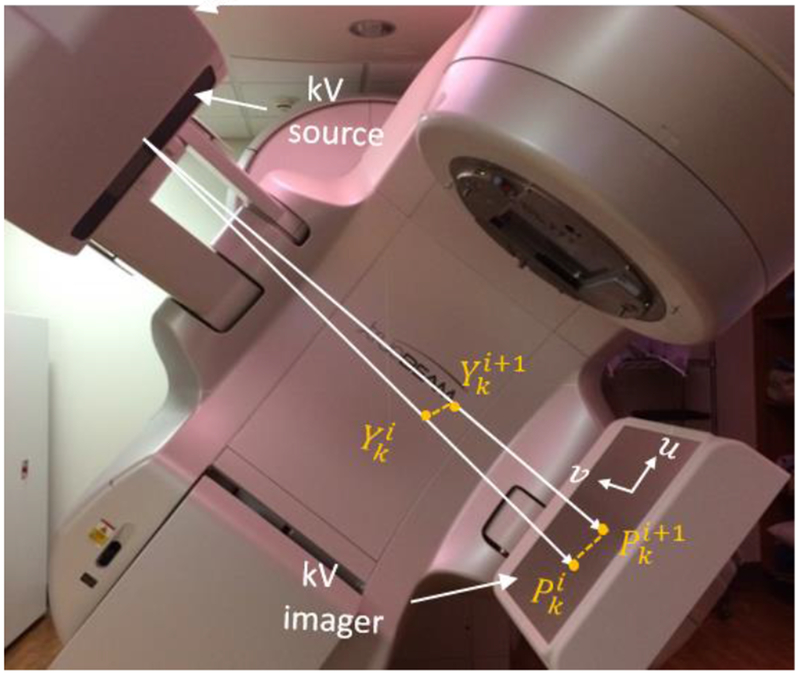

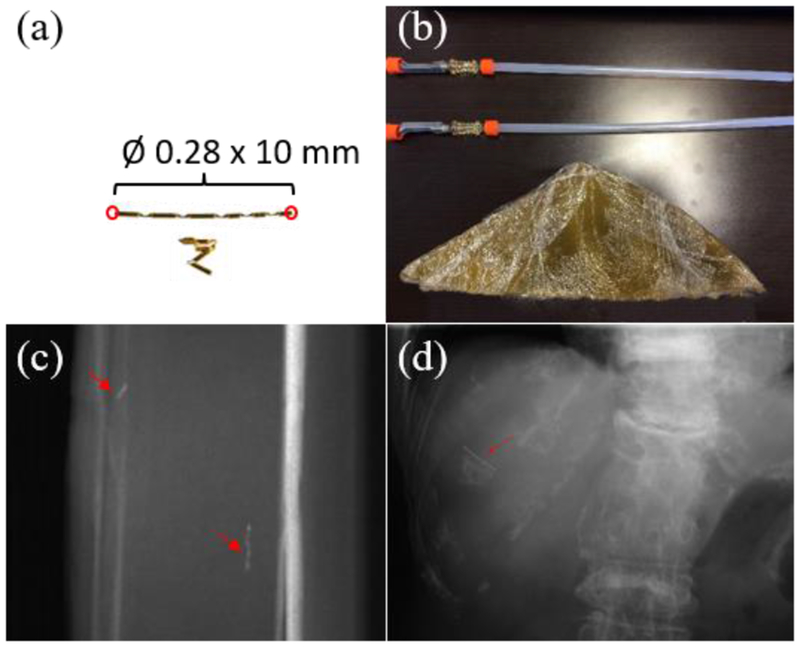

The proposed approach is the extension of Projection Marker Matching Method (PM3) that was previously developed by our group (Chi et al., 2017). Different from the previous method that can only reconstruct three DoF translational motion, the new approach considered both translational and rotational components. Hence, we call the new method six-Degree-of-Freedom Projection Marker Matching Method (6-DoF PM3). In our study, we used a Varian TrueBeam LINAC equipped with an on-board kV imaging system as the hardware platform (Fig. 1). Our method required two linear markers implanted into the liver tumor site (Fig. 2). During treatment delivery of a rotational radiotherapy plan, kV triggered imaging function available on the LINAC was employed to acquire 2D kV projection images every 3 sec. In each projection, four endpoints of the two linear markers were identified using image-processing techniques. Identified endpoints on the acquired kV projections were used to collectively determine the liver motion trajectory during the treatment delivery.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the kV imaging projection system.

Figure 2.

(a) Illustration of a gold linear marker with 0.28 mm in diameter and 10 mm in length. (b) Tissue equivalent liver phantom with two Gold Anchor™ Markers implanted. (c) A side-view kV projection image of the liver phantom. (d) A kV projection image of a patient case acquired at Maywa Hospital, Japan. Markers in (c) and (d) are indicated by the red arrows.

2.1. Algorithms

2.1.1. Two dimensional marker endpoints identification

The first step of our motion reconstruction method was to identify marker endpoints in a kV projection image. The 2D algorithm was developed based on the gold Anchor™ Marker (Naslund Medical AB, Huddinge, Sweden) as shown in Fig. 2(a), but the method is expected to be generalizable to other types of linear markers. The marker can be clearly visualized in a kV projection image obtained from both our phantom experiments (Figs. 2(c)) and in the kV projection for the liver site of a real patient (Fig. 2(d)) acquired at Maywa Hospital, Japan.

The idea of the 2D marker endpoint identification method was to use the rapid intensity change of the marker edges, linearity and continuity of the markers, to distinguish the markers from the background and other structures. The details of the method are described in the following seven steps.

(1) Identify the region of interest (ROI). A circular ROI was defined in the projection image for each marker. Based on the center of the marker in the patient treatment planning CT and the setup cone bean CT (CBCT), the 2D projection of the entire marker can be estimated within a circular region. The center of the circle was calculated by forward projecting the center of the 3D marker onto the kV imager at the corresponding projection angle, and the radius was estimated as where l is the length of the marker and Δ is the estimated motion range. SID and SAD are the distances from the kV focal spot to the kV imager and from the kV focal spot to the iso-center, respectively. In our case, with an estimation of motion range of 30 mm, r was set to be 30.0 mm, approximately 77 pixels for a detector with a pixel size of 0.388 mm. The final ROI was the combination of the ROIs for the two markers (Fig. 3(a)).

Figure 3.

2D marker endpoint identification method. (a) A ROI selected on the kV projection image. (b) The Laplacian image of the selected ROI. (c) The orientation direction map (in unit of degree) of the ROI image in (a) after the marker template matching. A marker template (17×17 pixels) at the orientation of zero degree is shown in the right corner of (c). (d) Two marker pixel groups selected based on thresholds on (b), orientation classification on (c) and some other criteria. (e) Finally determined marker endpoints (red).

(2) Perform Laplacian operation on the identified ROI. The intensities of the marker pixels typically varied for different parts of a marker or for different markers in a kV image (Fig. 3(a)), and for different projections among a CBCT scan. As a result, a simple threshold method on the projection image may not be effective. To solve this problem, we performed Laplace operation on the kV projection and multiplied it with the ROI mask to form the Laplacian image as shown in Fig. 3(b).

(3) Match templates. In order to get the two endpoints of a marker, it’s necessary to identify multiple points belonging to the same marker. Considering the background noise, simple cluster method to get the two marker groups may be problematic. To overcome this challenge, the marker orientation on the kV projection was computed via marker template matching. Specifically, a rectangular shape template (the sub-figure in Fig. 3(c)) was rotated seven times with an interval of 22.5° to generate eight templates along eight directions. The eight templates were then applied to pixels inside the ROIs. For each pixel, the highest normalized cross correlation among the eight-time matching was recorded together with the angular orientation θ of the corresponding template (Fig. 3(c)).

(4) Select marker group candidates. With the Laplacian and orientation images generated in Steps (2) and (3), we selected marker group candidates by iterating the following three sub-steps: i) select potential marker pixels by thresholding on the Laplacian image; ii) classify the selected points into different groups based on the continuous image regions formed with the same angular orientation; and iii) merge multiple groups, if the merged group has <60 pixels and coefficient of determination for the linear fitting of the pixels is larger than 0.6. These values were empirically chosen to generate satisfactory results in our tests. These sub-steps were performed, because a marker may not be implanted in an exact linear shape, hence it’s necessary to regroup points belonging to the same marker that was incorrectly split into multiple groups. Steps i)-iii) were iterated by increasing/decreasing the threshold in step i) until 2~5 groups were finally identified.

(5) Select final marker groups and identify marker endpoint positions. We selected the two groups with the largest number of pixels as the final maker groups (Fig. 3(d)). For each group, the two points with the largest separation were taken as the marker endpoints (Fig. 3(e)).

(6) Establish point correspondence. It is necessary to set the correspondence between each endpoint of the linear markers and the identified endpoints. Noticing that although the marker shape and position on the kV projection varied among projection angles, the relative positions of endpoints along the gantry rotational axis direction (i.e. the v direction in Fig. 1) didn’t have a big change. Hence, we could use this relation to set the correspondence of the marker endpoints.

2.1.2. Six-DoF target motion trajectory reconstruction

The identified 2D marker endpoints were used to reconstruct the 6-DoF target motion trajectory. The idea was to use the 2D-3D registration approach to determine the target position in the direction perpendicular to the x-ray projection direction, and use the temporal correlation of marker positions among different projections to estimate the missing position information along the x-ray projection direction. Specifically, based on marker endpoints on projection images taken at the moment k (k = 1, 2, …, N), the translational (Tk) and rotational (Rk) motion components of the target were determined by matching projections of the estimated 3D marker endpoints () with corresponding identified 2D positions (Fig. 1). Temporal correlation was assumed and employed as a regularization on the solution. This was formatted as an optimization problem:

| (1) |

where represents the 3D positions for the n marker endpoints (here, n = 4) in N projections, with being the (3n(k − 1) + 3(i − 1)+j)th element, indicating the position component along direction j (j = 1, 2, 3) for marker i at projection moment k. is an array containing all the rotation matrices and is the vector of all the translation vectors.

In the objective function, the first term is data fidelity. Based on the identified 2D marker endpoints and x-ray source positions , we can define straight lines (with unit vectors of ) connecting the x-ray source positions to the projected maker endpoints on the imager. As each 3D marker endpoint should be on a corresponding line, the data fidelity term minimized the distances between marker’s positions and the corresponding projection lines. This was quantitatively described by the term E(Y) as

| (2) |

Motion correlation was ensured by the second term of the objective function, which penalized the 3D distances between marker positions at subsequent moments. D is a differential operator along the temporal direction. Based on the rule to order the marker 3D coordinates in the vector Y, the specific format of D is

| (3) |

where (a, b) denotes row a and column b in the matrix D, with a, b = 1, 2, 3, …, 3Nn. After applying D to Y, it forms a new vector (DY), with for k = 1, 2, 3, …, N − 1, and .

Lastly, motion consistency was enforced by minimizing the distance between the estimated 3D marker endpoints Y and those derived by applying the operations of rotation R and translation T on reference marker endpoints X identified on the planning CT. α and β were weights controlling relevant contributions among the three terms. In this study, they were empirically selected for the best resulting accuracy.

The optimization problem in Eq. (1) was not convex. However, a closed form solution exists to match two groups of points in a 3D Cartesian space through rotational and translational operations (Horn, 1987). Motivated by this, we proposed a heuristic approach to solve the optimization problem by iteratively minimizing Y* and R*, T*. Specifically, we first fixed the rotational and translational parts, R* and T*, and optimized with respect to Y*. In this situation, the problem was equivalent to solving the optimization problem formed as:

| (4) |

where t is the index of iteration step. With known Rt−1 and Tt−1, solving Yt is equivalent to solving a linear equation AYt = bt. From Eqs. (2) and (4), A can be expressed as

| (5) |

and b is

| (6) |

The solution to the linear problem then can be derived as Yt = A−1bt.

Second, with the updated Yt, we optimized R* and T* as:

| (7) |

This problem tried to move points X via a rotation and a translation operation to match with points Y, which was solved via the Horn’s quaterion-based method (Horn, 1987). Horn (1987) proposed a quaterion-based method in which unit quaterion was applied to represent the rotation and consequently the closed form solution to the least squares problem for three or more points could be directly derived without iteration, thus making the solving process efficient.

The two steps were iterated, until a stopping criterion was met, such that the relative change of the marker positions between two adjacent iteration steps was equal or less than a threshold ϵ. We summarized the two-step alternating direction optimization approach in Table 1. As the optimization model is non-convex, the final accuracy could be affected by local minima. Hence, the initial inputs of R0 and T0 are of critical importance. Considering that in our previously developed PM3 method (Chi et al., 2017), translational motion can be estimated with a high level of accuracy, we took the translational vector obtained from the PM3 algorithm as T0. As for R0, we used the unit matrix (no rotation) as the initial solution.

Table 1.

Numerical algorithm to solve the problem in Eq. (1)

| Input: α, β, R0, T0 and a stopping criteria ϵ |

| Output: Y* and R*, T* |

| Procedure: Set t = 1; |

| 1. Compute Yt by solving the problem in Eq. (4) using Eqs. (5) and (6); |

| 2. Compute Rt and Tt by solving the problem in Eq. (7) using the Horn’s quaterion-based method; |

| 3. If max (|Yt−Yt−1|/|Yt|) ≤ ∈, Y* = Yt, R* = Rt and T* = Tt; otherwise, set t = t + 1, go to Step 1. |

2.2. Test cases

2.2.1. Two dimensional marker endpoints identification

We tested the accuracy of the 2D marker endpoints identification algorithm using real experimental data, with the experimental details given in section 2.2.2. For these experiments, two sets of CBCT scans and five sets of kV triggered imaging, for a liver phantom (Fig. 2(b)) in both static (1 set) and motion (4 sets) modes, were performed. A total of 1096 kV projections were acquired (498 images/CBCT scan and 20 images/triggered imaging set). 2D marker endpoints in these projection images were identified using our algorithm and compared with ground truth obtained from manual examination.

2.2.2. 6-DoF target motion trajectory reconstruction

We performed both simulation and phantom experiments to test the accuracy of the motion trajectory reconstruction method. The simulation study was performed in order to test the algorithm’s performance in an ideal setup and to investigate the sensitivity of motion reconstruction accuracy to 2D marker position accuracy. The phantom experiments were conducted as an end-to-end test of the overall performance in a clinical setting, with considering different forms of system uncertainties, including inaccurate x-ray projection geometry due to gantry wobbling.

Motion type

In both simulation and phantom experiments, three types of motions were considered: translational motion (TM) only, rotational motion (RM) only and translational plus rotational motion (TRM). Specifically, for the TM case, since we didn’t have liver tumor motion trajectories acquired in real patients, we used a lung tumor motion trajectory acquired in our clinic. We expect this is a reasonable approach, as a major component of liver tumor motion was caused by respiration. For the RM case, we first tested the rotational motion around each of the three major axes. The rotation angles were sampled following an oscillation with 2° interval and an amplitude of 14° on one of the axes and no rotation on the other two axes. We then test more complicated cases with rotations along all three directions. The rotating angle amplitude along LR (pitch), AP (yaw) and SI (roll) axes were set to be 12°, 10° and 20°, respectively. The total rotation was calculated as mutilation of elemental rotations along these three directions.

Simulation study

We arbitrarily set four points in 3D with coordinates [−4, 0, 0; 6, 0, 0; 2, −2, −4; −1.5, 6, 1] mm (in the order of LR, AP and SI directions) as the reference marker endpoints X. For each moment, the known rotation and/or translation were applied to the reference points, forming a ground truth 3D motion trajectory. This motion trajectory was then forward projected under the corresponding gantry angle. The gantry angles were uniformly distributed within an arc with an 18° interval to mimic projection acquisition of every 3 seconds. Based on the simulated 2D projection points, the 3D motion trajectory was reconstructed using our algorithm. The complex TRM type motion was further tested, when a 2D error was introduced to the projected 2D marker endpoint positions. We considered error sampled from to a normal distribution with a mean value of zero and standard deviations of 0.22mm, 0.44mm, 0.388mm and 0.776mm, to study the sensitivity of motion reconstruction accuracy with respect to the error.

Although the minimum interval of 3 seconds from the Varian Truebeam system was imposed in our study, there should be no problem to reconstruct the motion trajectory for a higher acquisition frequency with our method. To demonstrate it, we performed a simulation test with a 0.3 sec time interval for the TM type motion.

Phantom experiment

A liver phantom (Fig. 2(b)) was made by tissue equivalent material (Superflab Bolus Material™, Nuclear Associates, NY, USA) and two gold anchor markers were implanted in a linear shape into the phantom. The phantom was driven in two different ways. First, to acquire TM data, the phantom was driven by a 4D motion platform (Malinowski et al., 2007) with an input of the real patient lung motion trajectory. kV triggered images and MV images were taken simultaneously every 3 sec with the gantry rotation speed of 1 rotation/min. The parameters of the kV source were 110 kVp, 20 mA and 10 ms. For the MV images, a 2.5x beam with 3 MUs was used for each projection. The purpose of acquiring MV images was to obtain the ground truth of the 3D marker endpoint trajectory using the orthogonal MV/kV triangulation. However, the MV images were not used by our algorithm for motion reconstruction.

Second, to acquire the data for the RM and TRM cases, since we did not have a motion platform that can achieve rotational motions, the phantom motion was realized by couch shift and couch/gantry rotation manually. Specifically, for different projection angles, the corresponding phantom positions were calculated from the designed motion trajectory. As for the rotation along the AP axis, shift and rotation (yaw) were directly applied to the couch to move it to the calculated position, followed by taking kV and MV projections. This was repeated to realize data acquisition of a full gantry rotation. As for the rotation along the SI axis, since the phantom rotation (roll) and the gantry rotation were along the same axis, the rotation was realized by equivalently changing the gantry angle. For instance, taking a projection at gantry angle α with a phantom rotation of Δα (roll) was assumed to be equivalent to taking the projection at gantry angle (α − Δα) without phantom rotation.

In the experimental tests, marker endpoints on kV/MV projection images were identified both manually and using our 2D identification algorithm. Through triangulation of marker endpoints manually identified in kV and MV images at each projection moment, 3D marker positions were calculated as ground truth. 3D marker positions were also reconstructed using our 6-DoF motion reconstruction algorithm using the kV projection images.

Evaluation parameters

In both simulation and phantom experiment studies, difference between 3D marker endpoint positions calculated by our algorithm and the ground truth was calculated. Root-mean-square (RMS) error was used to quantify the reconstruction accuracy. Percentage of time for reconstruction error exceeding certain ranges was calculated to evaluate stability of the reconstruction algorithm. The mean difference and standard deviation of the difference between the reconstructed translational and rotational motion and the ground truth motion were also computed.

2.2.3. Parameter study and computational efficiency

The optimization problem for the 6-DoF motion reconstruction (Eq. (1)) is not convex. It can be hard to find a global minimum or even a true local minimum. Tests have to be performed to establish proper initial solutions and optimal parameters. In our study, we tested the algorithm performance in two initial solution conditions: a trivial starting point (R0 = I and T0 = 0 or other random values) and the solution from the original PM3 method. We also explored the algorithm behavior for different combinations of the weighing factors α, β (Eq. (1)) and the stopping criteria ϵ (Table 1) in a relatively broad range of [10−9, 102]. The accuracy, convergence and robustness of the algorithm were taken as evaluation criteria.

With the optimal parameters selected, computational efficiency for the 2D marker endpoint identification and the 6-DoF motion reconstruction was evaluated for both simulation and phantom experimental studies.

3. RESULTS

3.1. 2D marker identification

Error distributions for a total of 4384 marker endpoint positions from 1096 projection images are shown in Fig. 4. 99.98% and 99.91% of the marker endpoints were identified with an error ≤ 0.388 mm (1 pixel) along the u and v directions, respectively. The errors for all marker endpoint positions were within 3 pixels, implying the accuracy and robustness of our algorithm.

Figure 4.

Error distribution of the 2D marker endpoints along (a) u and (b) v directions.

3.2. Six-DoF target motion trajectory reconstruction

3.2.1. Simulation studies

Ideal cases

Simulation studies were first performed on a group of cases assuming accurate 2D marker positions. The statistical evaluation on the reconstruction accuracy based on the four marker endpoints on 40 projections for each motion scenario are summarized in Table 2 as ‘Simulation I’. For the RM type, the RMS errors were within 9.1 × 10−3 mm and there was no reconstructed marker position with error exceeding 0.5 mm. It indicates the capability of the 6-DoF PM3 algorithm in terms of accurately recovering the rotational motion trajectory in an ideal scenario. For the TM and TRM types, the RMS errors were within 0.49 mm. The percentages for motion error exceeding 1.0 and 1.5 mm were 5% and 0%.

Table 2.

RMS errors, 3D RMS error and percentage of time for motion errors exceeding 1.0 and 3.0 mm in simulation studies -- I. without noise in the 2D marker positions, II. with different levels of errors in 2D marker positions and III with an image acquisition frequency of every 0.3 sec, and in phantom experiments.

| Cases | Motion type | Motion range ([LR, AP, SI]) | RMS error (mm) | Percentage of time with 3D error > a threshold (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (mm) | R | LR | AP | SI | 3D | 1.0 | 3.0 | |||

| Simulation I | TM | [3.5, 7, 8] | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.00 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 0.0 | |

| RM | AP 28° | 6.9e-3 | 3.8e-3 | 8.0e-6 | 7.8e-3 | 0.0 | |||

| SI 28° | 7.4e-3 | 5.3e-3 | 1.1e-5 | 9.1e-3 | 0.0 | ||||

| TRM | [3.5, 7, 8] | AP 28° | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | |||

| [3.5, 7, 8] | SI 28° | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | ||||

| [3.5, 7, 8] | [24°,20°,40°] | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | ||||

| Simulation II | TRM | [3.5, 7, 8] | [24°,20°,40°] with 2D noise (mm) ([μ, σ]) | [0, 0.22] | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 54 | 10 |

| [0, 0.44] | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 53 | 7.5 | |||

| [0, 0.388] | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 56 | 7.5 | |||

| [0, 0.776] | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 51 | 12 | |||

| Simulation III | TM | [1, 6, 8] | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1e03 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Phantom experiment | TM | [3.5, 7, 8] | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 31 | 5.0 | |

| RM | AP 28° | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 40 | 0.0 | ||

| SI 28° | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.0 | |||

| TRM | [3.5, 7, 8] | SI 28° | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 54 | 5.0 | ||

We calculated the mean and standard deviation of the error for the decomposed rotational angles along LR (pitch), AP (yaw) and SI (roll) directions for the above simulation studies. In all the cases, the errors were negligible (less than 10−3 degree), as shown in Table 3 ‘Simulation I’. These results further confirmed the capability of the 6-DoF PM3 algorithm in terms of accurately recovering the rotational component in the ideal scenario.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation of rotational angle errors in simulation studies -- I. without noise in the 2D marker positions and II. with different levels of errors in 2D marker positions, and in phantom experiments.

| Cases | Motion Type | Mean ± std. (°) of rotational angle errors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR (pitch) | AP (yaw) | SI (roll) | |||

| Simulation I | TM, RM, TRM | < 10−3 | |||

| Simulation II | TRM with 2D noise level (mm) ([μ, σ]) | [0, 0.22] | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| [0, 0.44] | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | ||

| [0, 0.388] | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | ||

| [0, 0.776] | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | ||

| Phantom experiment | TM | 0.1 ± 0.2 | −0.6 ± 0.3 | −0.8 ± 0.4 | |

| RM | AP | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | |

| SI | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | ||

| TRM | SI | −0.1 ± 0.2 | −1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | |

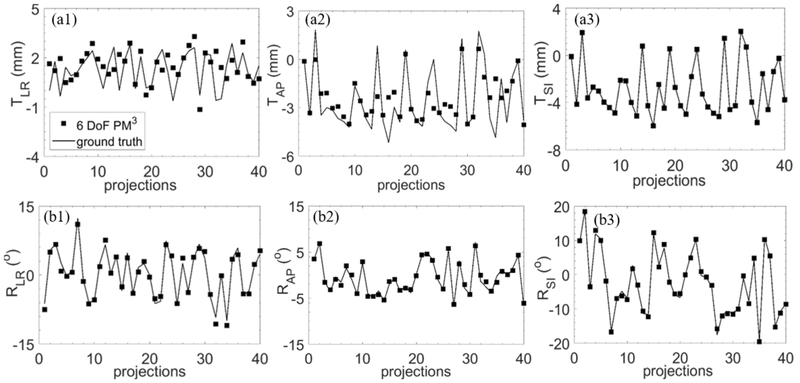

The reconstructed 3D coordinates for a representative marker endpoint under the TRM type are shown in Fig. 5. Errors along LR, AP and SI directions were also plotted.

Figure 5.

Top row: marker trajectories reconstructed with the 6-DoF PM3 method and that of the ground truth, along (a1) LR, (a2) AP and (a3) SI directions, in a simulation study of TRM type assuming accurate 2D marker positions. Bottom row: the reconstruction errors along the three directions.

Sensitivity with respect to 2D position accuracy

The complex TRM cases were further investigated in terms of result sensitivity with respect to the 2D marker positions accuracy. We repeatedly performed motion reconstruction, each time perturbing the 2D marker positions with randomly sampled errors. For each reconstruction result, we computed the RMS error. We then calculated the mean RMS errors over these runs. The results are summarized in Tables 2–3 as ‘Simulation II’. In Table 2, it was found that the mean 3D RMS error slightly increased from 1.612 mm to 1.672 mm, when the standard deviation of the 2D position error raised from 0.22 mm to 0.776mm. The corresponding rotational angle error was found more sensitive to the 2D error of marker positions, as shown in Table 3. The means±standard deviations were increased from (0.65 ± 0.43)° to (2.51 ± 1.89)°, (0.49 ± 0.37)° to (1.90 ± 1.19)°, and (0.59 ± 0.37)° to (1.93 ± 1.43)°, along LR, AP and SI directions respectively, when the 2D errors increased from 0.22 mm to 0.776mm. Slightly increased translational error was also observed with increased error level. Fig. 6 presents the results of reconstructed translational and rotational components in one representative case with the standard deviation of 2D marker position error being 0.22 mm.

Figure 6.

Translation (top row) and rotation angle (bottom row) along LR, AP and SI directions in a representative simulation case with the standard deviation of 2D marker position error being 0.22 mm.

Impact from the image acquisition frequency

The 3D RMS error was found to be reduced from 0.465 mm to 0.115 mm when the time interval was shortened from 3 sec to 0.3 sec for the TM type motion trajectory. The reconstructed 3D coordinates for a representative marker endpoint under the 0.3 sec interval are shown in Fig. 7. Errors along LR, AP and SI directions were also plotted. The RMS errors for each direction and the 3D RMS error were summarized in Table 2 as ‘Simulation III’. A potential explanation of the improved accuracy is that with a smaller time interval, the motion magnitude between two adjacent projection moments is smaller, hence better satisfying the temporal correlation term in Eq. (1).

Figure 7.

Top row: marker trajectories reconstructed with the 6-DoF PM3 method and that of the ground truth, along (a1) LR, (a2) AP and (a3) SI directions, in a simulation study of TM type with a projection interval of 0.3 sec. Bottom row: the reconstruction errors along the three directions.

3.2.2. Phantom studies

The results of the phantom experiments are shown in Tables 2–3 as ‘phantom expriments’. As shown in Table 2, the 3D RMS error for the RM type was within 0.97 mm. As for the TM and TRM types, the RMS errors were within 1.25 mm. For the reconstruction stability, in no more than 5% of the time, the reconstructed motion had error exceeding 2 mm. The mean and standard deviation of the reconstructed rotational angles for the TM, RM and TRM cases in the phantom experiment are then shown in Table 3. For all the tested cases, the mean error of the reconstructed rotational angles was within 1.7° with the standard deviation less than 1°.

3.3. Parameter study and computational efficiency

The 6-DoF PM3 algorithm experienced a slow convergence with a trivial starting point (R0 = I and T0 = 0 or other random values) in our test. It was also impossible to find an optimal parameter set. Yet, with the solution from the original PM3 algorithm being the initial solution, the speed of the convergence was improved by 1~2 orders. Based on it, the parameter set of α = 1, β = 10−6 and ϵ = 5 × 10−7 was found optimal to all test cases.

In the current Matlab based coding version, the computational time for the 2D marker endpoint identification algorithm to identify four marker endpoints from one projection was ~0.31 sec. The corresponding reconstruction for the 6 DoF motion was ~1s for the test cases.

4. DISCUSSIONS

The 2D marker identification algorithm was found accurate and robust when testing with the phantom data. However, when there is overlap between the two markers, there may be a concern on its accuracy. In our experiment, we have acquired a set of triggered images in which ends of the two markers jointed together. After applying our algorithm, the several points at the overlapped region (the three white pixels in Fig. 8(b)) were found identified by both markers. The final marker endpoints were identified with an error within 1 pixel, demonstrating the robustness of our algorithm. Yet it is necessary to further examine this situation in detail, as more complex situations, e.g. with markers crossing, may occur.

Figure 8.

The illustration of the performance of the 2D marker identification algorithm to identify markers with overlap. (a) The kV projection data and (b) the corresponding marker identification results. Points labeled with 1 (yellow) and 2 (blue) are the two markers while the ones labeled with 3 (white) are the overlapped region.

Due to the lack of available patient data, we could not test the performance of the 2D algorithm on real patient images. Consequently, there are potential concerns for its application in real clinic, where the image quality could be affected by the patient structures, size, kV imaging parameters, etc. The image quality will in particular affect 2D marker endpoint identification algorithm. It is our next step work to comprehensively evaluate the algorithm using realistic data.

The current 3D algorithm is an extension of a previously developed PM3 algorithm by including reconstruction of the rotational component. We think the extension was not trivial and deserves a separate study. First, when rotation is included, the optimization problem is not convex anymore and there is no closed form solution. Here we proposed an alternating optimization algorithm. The two subproblems both have closed form solutions, which made it easy to tackle the problem. Second, as discussed in section 2.2.3, for a non-convex problem, it is not trivial to find a global minimum or a true local minimum. Yet through a relatively broad exploration, we are able to establish the proper initial solution and optimal parameters for the test cases.

Despite the motion tracking accuracy of the markers, several factors could influent the tumor tracking accuracy, including the location of tumor with respect to marker, marker deformation and/or mitigation, etc. Previous liver tumor motion study in real patients indicated that the motion of markers at different locations can show different level of correlations with the actual liver tumor (Park et al., 2012). To reconstruct meaningful tumor motion information, the fiducial markers should be implemented close to the gross tumor. As for the marker deformation and mitigation, this will break the assumption of rigid maker motions in our algorithm and hence may affect its performance. We investigated this issue with simulation studies in which independent 3D Gaussian noises were added to the initial rigid 3D trajectories of the four marker endpoints. The new trajectories were then projected and reconstructed with the developed 6 DoF PM3 method. The degree of the reconstruction error due to 3D noise was found similar to that caused by the 2D noise as discussed in section 3.2.1.

In the 6-DoF PM3 method, we determined the 6-DoF motion directly from measured x-ray projections. In previous works, 6-DoF KIM (Tehrani et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017) reconstructed the 6-DoF motion via two steps: 1) estimate the trajectory of each marker from a probability-based method and 2) obtain the 6-DoF motion by analyzing trajectories of multiple markers. In comparison, 6D-IDC (Nguyen et al., 2017) predicted the 6-DoF motion from the 2D kV projections under a linear correlation assumption between the translational motion along the superior-inferior direction and the motions in the rest 5 DoF. Comparable accuracies were found among the three methods. However, in the 6-DoF KIM, the trajectory prediction errors for any of the markers in the first step could affect the motion reconstruction accuracy in the second step, especially for the rotational components. In the 6D-IDC, the accuracy may be a concern when the correlation is weak (Nguyen et al., 2017). In both circumstances, the reconstruction accuracy of the 6-DoF PM3 method could be retained. Yet, compared to 6-DoF KIM and 6D-IDC, one limitation of the 6-DoF PM3 method is that it was designed to retrospectively reconstruct the intra-fractional liver motion, instead of in a prospective or real time manner.

The 6 DoF PM3 method can retrospectively reconstruct the intra-fractional liver motion after a rotational gantry delivery, such as VMAT treatment. With the intra-fractional motion information derived from it, we could perform 4D dose reconstruction of the delivered dose, allowing to adaptively replan the treatments in the remaining fractions. It may also be extended to prospectively tracking the motion during the treatment delivery. For this purpose, we could take pre-treatment images (e.g. in CBCT scanning), identify the marker endpoint positions and solve the motion trajectory. During treatment delivery, each newly acquired projection image can be appended to the existing image sequence, and the motion trajectory for the updated imaging sequence can be derived using our method. In this application, the computational time should be short, e.g., at the level of tens of milliseconds. In our current version (Matlab based), the computational time for the 2D marker endpoint identification algorithm to identify four marker endpoints from one projection was ~0.31 sec. The corresponding reconstruction for the 6 DoF motion was ~1s. This speed probably not sufficient for the acquisition frequency of every 3 sec. Further optimization of the two algorithms to improve computational efficiency will be performed in future.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we reported the development of 6 DoF PM3, a novel method to reconstruct the intra-fractional liver motion trajectories with both translational and rotational components for a rotational radiotherapy based on x-ray projections. Four endpoints from two linear markers were used as surrogates. To automatically identify the marker endpoints in a projection image, a 2D marker endpoint identification algorithm was developed. The algorithm was found to be accurate and robust based on tests performed on 1096 kV projections. The 6 DoF liver motion was restored by matching the projection of the marker endpoints with the measured positions under constrains of rigid translational, rotational motion and motion correlation along the temporal direction. Via simulation and experimental studies, we demonstrated the accuracy of 6 DoF motion reconstruction to determine the intra-fractional liver tumor motion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partially supported by an NIH grant R01CA227289. The authors highly appreciate Dr. Hiroshi Doi from the Maywa Hospital, Japan to provide us the 2D x-ray projection image of the marker in a patient case (Fig. 1c). We are also grateful to Dr. Johnny Mattebo from Gold Anchor™ for suggestive discussions.

REFERENCES

- Andratschke N, Geinitz H, Schill S, Gharbi N, Schratzenstaller U, Molls M, et al. 2009. Long-term follow up of 77 patients treated with hypofractionated stereotactic radiation therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases: Report of a single institution’s experience. Strahlenther Onkol 185 10–1 [Google Scholar]

- Arcangeli S, Castiglioni S, Mancosu P, Navarria P, Tozzi A, Alongi F, et al. 2012. Is Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) an Attractive Option for Unresectable Liver Metastases? Early Results From a Phase 2 Trial Int J Radiat Oncol 84 S3–S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet J, Knopf A, Eiben B, McClelland J, Grimwood A, Harris E, et al. 2019. Real-time intrafraction motion monitoring in external beam radiotherapy Phys Med Biol 64 15TR01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet J, Worm ES, Fledelius W, Hoyer M and Poulsen PR 2016. Time-Resolved Intrafraction Target Translations and Rotations During Stereotactic Liver Radiation Therapy: Implications for Marker-based Localization Accuracy Int J Radiat Oncol 95 802–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y, Rezaeian NH, Shen C, Zhou Y, Lu W, Yang M, et al. 2017. A new method to reconstruct intra-fractional prostate motion in volumetric modulated arc therapy Phys Med Biol 62 5509–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva T, Uneri A, Ketcha MD, Reaungamornrat S, Kleinszig G, Vogt S, et al. 2016. 3D–2D image registration for target localization in spine surgery: investigation of similarity metrics providing robustness to content mismatch Physics in Medicine and Biology 61 3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz AM, Haidegger T, Birkfellner W, Cleary K, Peters TM and Maier-Hein L 2014. Electromagnetic Tracking in Medicine-A Review of Technology, Validation, and Applications Ieee T Med Imaging 33 1702–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green OL, Rankine LJ, Cai B, Curcuru A, Kashani R, Rodriguez V, et al. 2018. First clinical implementation of real-time, real anatomy tracking and radiation beam control Med Phys [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke L, Kashani R, Robinson C, Curcuru A, DeWees T, Bradley J, et al. 2018. Phase I trial of stereotactic MR-guided online adaptive radiation therapy (SMART) for the treatment of oligometastatic or unresectable primary malignancies of the abdomen Radiother Oncol 126 519–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BKP 1987. Closed-Form Solution of Absolute Orientation Using Unit Quaternions J Opt Soc Am A 4 629–42 [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhou YK, Chen YX and Zeng ZC 2017. Magnitude and influencing factors of respiration-induced liver motion during abdominal compression in patients with intrahepatic tumors Radiat Oncol 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Tehrani JN, Ng JA, Booth J and Keall P 2015. Six degrees-of-freedom prostate and lung tumor motion measurements using kilovoltage intrafraction monitoring Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 91 368–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh BD, Schefter TE, Cardenes HR, Stieber VW, Raben D, Timmerman RD, et al. 2006. Interim analysis of a prospective phase I/II trial of SBRT for liver metastases Acta Oncol 45 848–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall PJ, Colvill E, O’Brien R, Ng JA, Poulsen PR, Eade T, et al. 2014. The first clinical implementation of electromagnetic transponder-guided MLC tracking Medical Physics 41 020702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Nguyen DT, Huang CY, Fuangrod T, Caillet V, O’Brien R, et al. 2017. Quantifying the accuracy and precision of a novel real-time 6 degree-of-freedom kilovoltage intrafraction monitoring (KIM) target tracking system Phys Med Biol 62 5744–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilova A, Lockwood G, Math M, Choi P, Bana N, Haider MA, et al. 2008. Three-dimensional motion of liver tumors using cine-magnetic resonance imaging Int J Radiat Oncol 71 1189–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K, Shirato H, Seppenwoolde Y, Shimizu T, Kodama Y, Endo H, et al. 2003. Tumor location, cirrhosis, and surgical history contribute to tumor movement in the liver, as measured during stereotactic irradiation using a real-time tumor-tracking radiotherapy system Int J Radiat Oncol 56 221–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu WG 2008. Real-time motion-adaptive delivery (MAD) using binary MLC: I. Static beam (topotherapy) delivery Physics in Medicine and Biology 53 6491–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu WG, Chen ML, Ruchala KJ, Chen Q, Langen KM, Kupelian PA, et al. 2009. Real-time motion-adaptive-optimization (MAO) in TomoTherapy Physics in Medicine and Biology 54 4373–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski K, Noel C, Lu W, Lechleiter K, Hubenschmidt J, Low D, et al. Medical Imaging 2007: Physics of Medical Imaging, Pts 1–3, 2007), vol. Series 6510) pp U148–U56 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JJ, Foster RD, Lev-Cohain N, Yokoo T, Dong Y, Schwarz RE, et al. 2015. A Phase I Dose-Escalation Trial of Single-Fraction Stereotactic Radiation Therapy for Liver Metastases Annals of surgical oncology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DT, Bertholet J, Kim J, O’Brien R, Booth J, Poulsen P, et al. 2017. An Interdimensional Correlation Framework for Direct Real-Time Estimation of Six Degree of Freedom Target Motion Using a Single X-Ray Imager During Radiotherapy Medical Physics 44 3268- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otake Y, Wang AS, Uneri A, Kleinszig G, Vogt S, Aygun N, et al. 2015. 3D–2D registration in mobile radiographs: algorithm development and preliminary clinical evaluation Physics in medicine and biology 60 2075–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JC, Park SH, Kim JH, Yoon SM, Song SY, Liu ZW, et al. 2012. Liver motion during cone beam computed tomography guided stereotactic body radiation therapy Medical Physics 39 6431–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen PR, Worm ES, Hansen R, Larsen LP, Grau C and Hoyer M 2015. Respiratory gating based on internal electromagnetic motion monitoring during stereotactic liver radiation therapy: First results Acta Oncol 54 1445–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen PR, Worm ES, Petersen JBB, Grau C, Fledelius W and Hoyer M 2014. Kilovoltage intrafraction motion monitoring and target dose reconstruction for stereotactic volumetric modulated arc therapy of tumors in the liver Radiother Oncol 111 424–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant A, Smith RL, Venkat RB, Santanam L, Cho B, Poulsen P, et al. 2009. Toward submillimeter accuracy in the management of intrafraction motion: the integration of real-time internal position monitoring and multileaf collimator target tracking International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics 74 575–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant A, Venkat R, Srivastava V, Carlson D, Povzner S, Cattell H, et al. 2008. Management of three-dimensional intrafraction motion through real-time DMLC tracking Medical Physics 35 2050–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schefter TE, Kavanagh BD, Timmerman RD, Cardenes HR, Baron A and Gaspar LE 2005. A Phase I trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases Int J Radiat Oncol 62 1371–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato H, Seppenwoolde Y, Kitamura K, Onimura R and Shimizu S 2004. Intrafractional tumor motion: Lung and liver Semin Radiat Oncol 14 10–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Sawant A, Santanam L, Venkat RB, Newell LJ, Cho BC, et al. 2009. Integration of Real-Time Internal Electromagnetic Position Monitoring Coupled with Dynamic Multileaf Collimator Tracking: An Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy Feasibility Study Int J Radiat Oncol 74 868–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani JN, O’Brien RT, Poulsen PR and Keall P 2013. Real-time estimation of prostate tumor rotation and translation with a kV imaging system based on an iterative closest point algorithm Physics in Medicine and Biology 58 8517–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetar S, Bruynzeel A, Bakker R, Jeulink M, Slotman BJ, Oei S, et al. 2018. Patient-reported Outcome Measurements on the Tolerance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging-guided Radiation Therapy Cureus 10 e2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uneri A, Silva TD, Stayman JW, Kleinszig G, Vogt S, Khanna AJ, et al. 2015. Known-component 3D–2D registration for quality assurance of spine surgery pedicle screw placement Physics in Medicine and Biology 60 8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worm ES, Hoyer M, Fledelius W and Poulsen PR 2013. Three-dimensional, Time-Resolved, Intrafraction Motion Monitoring Throughout Stereotactic Liver Radiation Therapy on a Conventional Linear Accelerator Int J Radiat Oncol 86 190–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]