Abstract

Purpose

We previously found a dominant mutation, Rwhs, causing white spots on the retina accompanied by retinal folds. Here we identify the mutant gene to be Tmem98. In humans, mutations in the orthologous gene cause nanophthalmos. We modelled these mutations in mice and characterised the mutant eye phenotypes of these and Rwhs.

Methods

The Rwhs mutation was identified to be a missense mutation in Tmem98 by genetic mapping and sequencing. The human TMEM98 nanophthalmos missense mutations were made in the mouse gene by CRISPR-Cas9. Eyes were examined by indirect ophthalmoscopy and the retinas imaged using a retinal camera. Electroretinography was used to study retinal function. Histology, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy techniques were used to study adult eyes.

Results

An I135T mutation of Tmem98 causes the dominant Rwhs phenotype and is perinatally lethal when homozygous. Two dominant missense mutations of TMEM98, A193P and H196P are associated with human nanophthalmos. In the mouse these mutations cause recessive retinal defects similar to the Rwhs phenotype, either alone or in combination with each other, but do not cause nanophthalmos. The retinal folds did not affect retinal function as assessed by electroretinography. Within the folds there was accumulation of disorganised outer segment material as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, and macrophages had infiltrated into these regions.

Conclusions

Mutations in the mouse orthologue of the human nanophthalmos gene TMEM98 do not result in small eyes. Rather, there is localised disruption of the laminar structure of the photoreceptors.

Introduction

There are a range of genetic disorders which present with a reduced eye size. In microphthalmia the reduced size is often associated with additional developmental eye defects, such as coloboma, and may also include developmental defects in other organs. In some cases there is an overall size reduction without other developmental defects. The smaller eye may be a result of a reduction in size of the anterior segment alone (anterior microphthalmos), the posterior segment alone (posterior microphthalmos) or a reduction of both. This last category includes simple microphthalmos and the more severe nanophthalmos 1, 2. Posterior microphthalmos is sometimes considered as part of a continuum with nanophthalmos, as they have pathological and genetic features in common. In nanophthalmos eye length is reduced by 30% or more, and is usually associated with other ocular features, notably a thickened choroid and sclera, as well as a high incidence of glaucoma, corneal defects, vascular defects and a range of retinal features including retinitis pigmentosa, retinoschisis, retinal detachments and retinal folds. Retinal folds are also observed in posterior microphthalmos, and are sometimes ascribed to a relative overgrowth of neural retina within a smaller globe, resulting in folding of the excess retinal tissue.

A number of genes have been found to be associated with nanophthalmos 2. Mutations in three genes have established associations with nanophthalmos. Several families with nanophthalmos have been found to have clear loss-of-function mutations in both alleles of the gene encoding membrane-type frizzled related protein, MFRP, that is expressed principally in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and ciliary body 3. Homozygous loss-of-function mutations in MFRP have been found in other individuals with posterior microphthalmia plus retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis and drusen, indicating likely genetic background effects on the severity or range of the disease 4–6. A second autosomal recessive nanophthalmos gene is PRSS56, encoding a serine protease. Families with biallelic mutations in this gene have been characterised, some of whom have posterior microphthalmia whilst others have nanophthalmos 7–9. There is no apparent genotype-phenotype correlation; there are patients with homozygous frameshift mutations with either condition. Intriguingly, association of variants at PRSS56 with myopia has been reported in genome-wide association studies 10, 11.

Most recently three families have been characterised in which heterozygous mutations in TMEM98 are segregating with nanophthalmos. Two families have missense mutations, the third has a 34bp deletion that removes the last 28 bases of exon 4 and the first six bases of intron 4 including the splice donor site12, 13. The effect of the deletion on the TMEM98 transcript is unknown but in silico splicing prediction programs (Alamut Visual Splicing Predictions) predict that it could result in exon 4 being skipped, and the production of a potentially functional protein with an internal deletion. Alternatively, other splice defects would result in frameshifts, nonsense mediated decay and loss of protein from this allele. In this case the cause of the disease would be haploinsufficiency. Caution in assigning a role for TMEM98 in nanophthalmos has been raised by findings in another study where different heterozygous missense mutations in TMEM98 were found in patients with high myopia and cone-rod dystrophy 14.

Patients with heterozygous or homozygous mutations in the BEST1 gene can have a range of defects 15. BEST1 encodes the bestrophin-1 protein, a transmembrane protein located in the basolateral membrane of the -RPE- 16. The predominant disease resulting from heterozygous mutations in BEST1 is Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, in which subretinal lipofuscin deposits precede vision defects 17. These patients in early stages have a normal electroretinogram (ERG) but have a defect in electrooculography (EOG) indicative of an abnormality in the RPE. This can progress to retinitis pigmentosa. Five families have been reported with dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy and nanophthalmos due to three different missense mutations in BEST1. Each mutant allele can produce two isoforms, one containing a missense mutation and one containing an in-frame deletion 18. On the other hand, homozygous null mutations of BEST1 result in high hyperopia accompanied by abnormal ERGs and EOGs and RPE abnormalities but lacking the vitelliform lesions found in the dominant disease19. Similar associations have been seen for mutations in the CRB1 gene that encodes an apical transmembrane protein important for determining cell polarity in photoreceptors 20. CRB1 mutations are most frequently found associated with recessive retinitis pigmentosa or with Leber congenital amaurosis and the disease phenotype observed in patients is very variable suggestive of the influence of genetic modifiers 21, 22. In addition, hypermetropia and short axial length are a common associations23. Furthermore, in two cases, both involving consanguineous families, the retinal dystrophy is associated with nanophthalmos 24, 25.

Mouse models with mutations in most of these genes have been analysed. Mice which have targeted disruption of the Best1 gene do not recapitulate the human bestrophinopathy phenotype or have only an enhanced response in EOG (indicative of a defect in the RPE) 26, 27. However, when the common human mutation, W93C, is engineered into the mouse gene, both heterozygous and homozygous mice show a distinctive retinal pathology of fluid or debris filled retinal detachments which progress with age 28. Spontaneous and targeted mutations in mouse Crb1 have been characterised, and they show similar, though not identical, recessive retinal phenotypes that had variable ages of onset 29–31. The defects found are focal. Folds appear in the photoreceptor layer that are visualised as white patches on retinal imaging. In a complete loss-of-function allele and the frameshift allele Crb1rd8 the folds are adjacent to discontinuities in the outer (external) limiting membrane (OLM) accompanied by loss of adherens junctions, and within them the photoreceptors, separated from the RPE, show degeneration 29, 30. In mice engineered to carry a missense mutation, Crb1C249W, that causes retinitis pigmentosa in humans, although the OLM appears intact, retinal degeneration still occurs, albeit later than in the other models 31. Similar to the human phenotype the extent of the retinal spotting observed in Crb1 mutants is strongly affected by the genetic background.

Two lines of mice with spontaneous mutations in Mfrp have been described 32–34. These do not recapitulate the nanophthalmic phenotype observed in humans. Instead both have the same recessive phenotype of white spots on the retina, which correlate with abnormal cells below the retina that stain with macrophage markers, and progress to photoreceptor degeneration. For the Mfrprdx mutation, atrophy of the RPE was reported 33 and for Mfrprd6 a modest ocular axial length reduction from about 2.87 to 2.83 mm was reported although apparently not statistically significant 35. A screen for mice with increased intraocular pressure (IOP) found a splice mutation in the Prss56 gene predicted to produce a truncated protein 8. The increased IOP was associated with a narrow or closed iridocorneal angle, analogous to that seen in human angle closure glaucoma. In addition these mice have eyes that are smaller than littermates, although the size reduction is variable and slight, ranging from 0 to 10% decrease in axial length. Reduction in axial length only becomes statistically significant after post-natal day seven. More recently it has been shown that mice deficient for Prss56 have eyes with a decreased axial length and hyperopia 36.

In summary the human nanophthalmos mutations modelled in mice produce either a much less severe, or non-significant, axial length reduction (Prss56, Mfrp) or no effect on eye size (Best1, Crb1). There are differences in the development of human and mouse eyes which probably underlies the differences in mutant phenotype.

To date no mouse models of TMEM98 have been reported. We describe here characterisation of a mouse mutation in Tmem98, which results in a dominant phenotype of retinal folds. In addition we engineer the two human nanophthalmos-associated missense mutations of TMEM98 into the mouse gene and show that these mice also, when homozygous or when compound heterozygous, have the same retinal fold phenotype but do not have a statistically significant reduction in eye size.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mouse work was carried out in compliance with UK Home Office regulations under a UK Home Office project licence and experiments adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Clinical examinations were performed as previously described 37. Fundus imaging was carried out as described 38. Mice carrying a targeted knockout-first conditional-ready allele of Tmem98, Tmem98tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi (hereafter Tmem98tm1a), were obtained from the Sanger Institute 39. Tmem98tm1a/+ mice were crossed with mice expressing Cre in the germ-line to convert this ‘knockout-first’ allele to the reporter knock-out allele Tmem98tm1b(EUCOMM)Wtsi (hereafter Tmem98tm1b). In this allele the DNA between the loxP sites in the targeting cassette which includes the neo selection gene and the critical exon 4 of Tmem98 is deleted. To create the Tmem98H196P allele the CRISPR design site http://www.crispr.mit.edu was used to design guides and the selected guide oligos ex7_Guide1 and ex7_Guide2 (Supplementary Table S1) were annealed and cloned into the Bbs I site of the SpCas9 and chimeric guide RNA expression plasmid px330 40 (pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 was a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid #42230, https://www.addgene.org/)). Following pronuclear injection of this plasmid along with repair oligo H196P (Supplementary Table S1) the injected eggs were cultured overnight to the 2-cell stage and transferred into pseudopregnant females. To create the Tmem98A193P allele Edit-R crRNA (sequence 5’-CCAAUCACUGUCUGCCGCUG-3’) (Dharmacon) was annealed to tracrRNA (Sigma) in IDT Duplex buffer (IDT). This, along with Geneart Platinum Cas9 nuclease (Invitrogen B25641) and repair oligo A193P (Supplementary Table S1) were used for pronuclear injection as described above. Pups born were screened for the targeted changes by sequencing PCR fragments generated using the oligos ex7F and ex7R (Supplementary Table S2) and lines established carrying the targeted missense mutations. Genotyping was initially done by PCR, and sequencing where appropriate, using the primers in Supplementary Table S2. Subsequently most genotyping was performed by Transnetyx using custom designed assays (http://www.transnetyx.com). All lines were maintained on the C57BL/6J mouse strain background.

DNA Sequencing

The candidate interval was captured using a custom Nimblegen array and sequenced with 454 technology by Edinburgh Genomics (formerly known as GenePool) (http://www.genomics.ed.ac.uk).

Bioinformatics

Multiple protein sequence alignments were generated with the program Clustal Omega41. The possible impact of missense mutations on protein structure and function was evaluated using Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/)42. HMM-HMM comparison was used for protein homology detection43. For protein structure prediction Phyre2 was used (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/)44. We used PyMOL for protein structure visualization45. SCWRL46 and the FoldX web server47 were used to evaluate the effect of amino acid substitutions on protein stability.

Electroretinography

Prior to electroretinography mice were dark adapted overnight (>16 hours) and experiments were carried out in a darkened room under red light using an HMsERG system (Ocuscience). Mice were anesthetised using isofluorane and their pupils dilated by the topical application of 1% w/v tropicamide. Three grounding electrodes were placed subcutaneously (tail, and each cheek) and silver embedded electrodes were positioned on the corneas using hypromellose eye drops (2.5% methylcellulose coupling agent) held in place with a contact lens. Animals were kept on a heated platform to maintain them at 37°C and monitored using a rectal thermometer. A modified QuickRetCheck (Ocuscience) protocol was used for obtaining full-field scotopic ERGs. Briefly, 4 flashes at 10 mcd.s/m2 at 2 s intervals were followed by 4 flashes at 3 cd.s/m2 (at 10 s intervals) and then 4 flashes at 10 cd.s/m2 (at 10 s intervals).

Histology and Immunostaining

Mice were culled, eyes enucleated and placed into Davidson’s fixative (28.5% ethanol, 2.2% neutral buffered formalin, 11% glacial acetic acid) for 1 hour (cryosectioning) or overnight (wax embedding) except for the eye used for Fig. 1 which was placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours before immersion in Davidson’s fixative. Prior to wax embedding eyes were dehydrated through an ethanol series. Haematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on 5 or 10 μm paraffin embedded tissue sections and images captured using a Nanozoomer XR scanner (Hamamatsu) and viewed using NDP.view2 software. For cryosectioning, fixed eyes were transferred to 5% sucrose in PBS and once sunk transferred to 20% sucrose in PBS overnight. Eyes were then embedded in OCT compound and cryosectioned at 14 μM. For immunostaining on cryosections, slides were washed with water then PBS and post-fixed in acetone at -20°C for 10 minutes. They were then rinsed with water, blocked in 10% donkey serum (DS), 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS (TBST) for one hour and then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in TBST with 5% DS for two hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, after washing with TBST, the slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) diluted 1:400 in TBST with 5% DS at room temperature for one hour. Following washing with TBST coverslips were mounted on slides in Prolong Gold (ThermoFisher Scientific) and confocal images acquired on a Nikon A1R microscope. Images were processed using either NIS-Elements or ImageJ software.

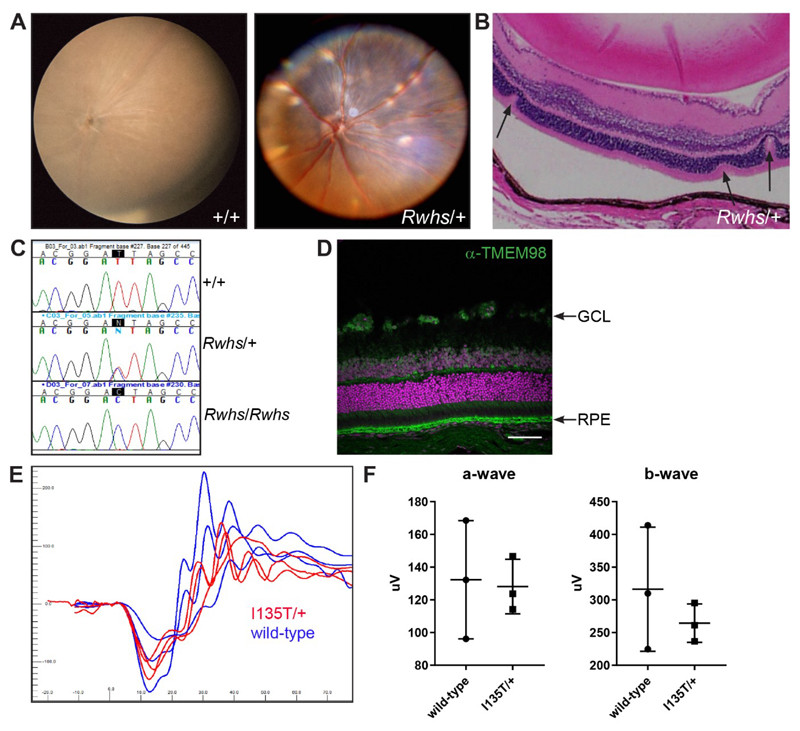

Figure 1.

The Rwhs mutation is caused by an I135T mutation of the transmembrane gene Tmem98. (A) Retinal images of wild-type (+/+) and Rwhs/+ eyes. Scattered white spots are present on the Rwhs/+ retina. (B) Rwhs/+ retinal section with three folds in the outer nuclear layer indicated by arrows. The separation of the RPE from the outer segments is a fixation artefact (C) Genomic DNA sequence traces from exon 5 of Tmem98 from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous mutant (Rwhs/+) and homozygous mutant (Rwhs/Rwhs) embryonic samples. The position of the T-to-C transition at position 404 (404T>C) in the coding sequence of Tmem98 is highlighted. (D) A section of wild-type retina immunostained for TMEM98 (green). Prominent staining is seen in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and there is also some staining in the ganglion cell layer (GCL). DNA is shown in magenta. (E) Tmem98I135T/+ mice have a normal ERG response. Shown are the responses at 3 cd.s/m2 (average of 4 flashes) for the left eye of three Tmem98I135T/+ mice (5-6 months of age) in red and three wild-type mice (5 months of age) in blue. (F) Comparison of a-wave amplitudes (right) and b-wave amplitudes (left), average of left and right eye for each mouse. There is no significant difference between Tmem98I135T/+ and wild-type mice (a-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.87 and b-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.45). Scale bar: 100 μM (D).

Eye size Measurement

Eyes from male mice were enucleated and kept in PBS prior to measuring to prevent drying out. The analysis was restricted to males as significant differences in axial length have been reported in the C57BL/6J strain between male and female mice48. Axial length measurements were made from the base of the optic nerve to the centre of the cornea using a Mitutoyo Digital ABS Caliper 6"/150mm, item number: 500-196-20.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used are listed in Table 1. DNA was stained with TOTO-3 (Invitrogen) or 4',6-Diamidine-2'-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI).

Table 1. Primary antibodies.

| Antibody | Source | Product No | Concentration used |

|---|---|---|---|

| anti-TMEM98 | proteintech | 14731-1-AP | 1:5000 (WB), 1:100 (IF) |

| anti-α-Tubulin | Sigma-Aldrich | T5168 | 1:10,000 (WB) |

| anti-Prominin 1 | proteintech | 18470-1-AP | 1:100 (IF) |

| anti-Rhodopsin | Millipore | MAB5356 | 1:500 (IF) |

| anti-ML Opsin | Millipore | AB5405 | 1:500 (IF) |

| anti-GFAP | abcam | ab7260 | 1:500 (IF) |

| anti-β-Catenein | Cell Signaling Technology | 19807S | 1:500 (IF) |

| Anti-F4/80 | AbD Serotec | MCA497EL | 1:500 (IF) |

Key: WB=Western blotting, IF=immunofluorescence

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Samples were fixed in 2% EM grade glutaraldehyde (TAAB Laboratory Equipment, Aldermaston, UK) in sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C overnight, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (Agar Scientific, Essex, UK), dehydrated in increasing concentrations of acetone and impregnated with increasing concentrations of epoxy resin (TAAB Laboratory Equipment). Embedding was carried out in 100% resin at 60°C for 24 hours. Semi-thin survey sections of 1 μm, stained with toluidine blue, were taken to determine relevant area. Ultrathin sections (approximately 70 nm) were then cut using a diamond knife on a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica, Allendale, NJ, USA). The sections were stretched with chloroform to eliminate compression and mounted on Pioloform-filmed copper grids (Gilder Grids, Grantham UK). To increase contrast the grids were stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and lead citrate (Leica). The grids were examined using a Philips CM 100 Compustage (FEI) Transmission Electron Microscope. Digital images were collected using an AMT CCD camera (Deben UK Ltd., Suffolk, UK).

Statistics

For the data shown in Figures 1, 2, 3 and Supplementary Figure S7 the graphs were created and unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction were performed using the program Graphpad Prism. For the data shown in Tables 2, S3 and S4 chi square tests were performed using http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

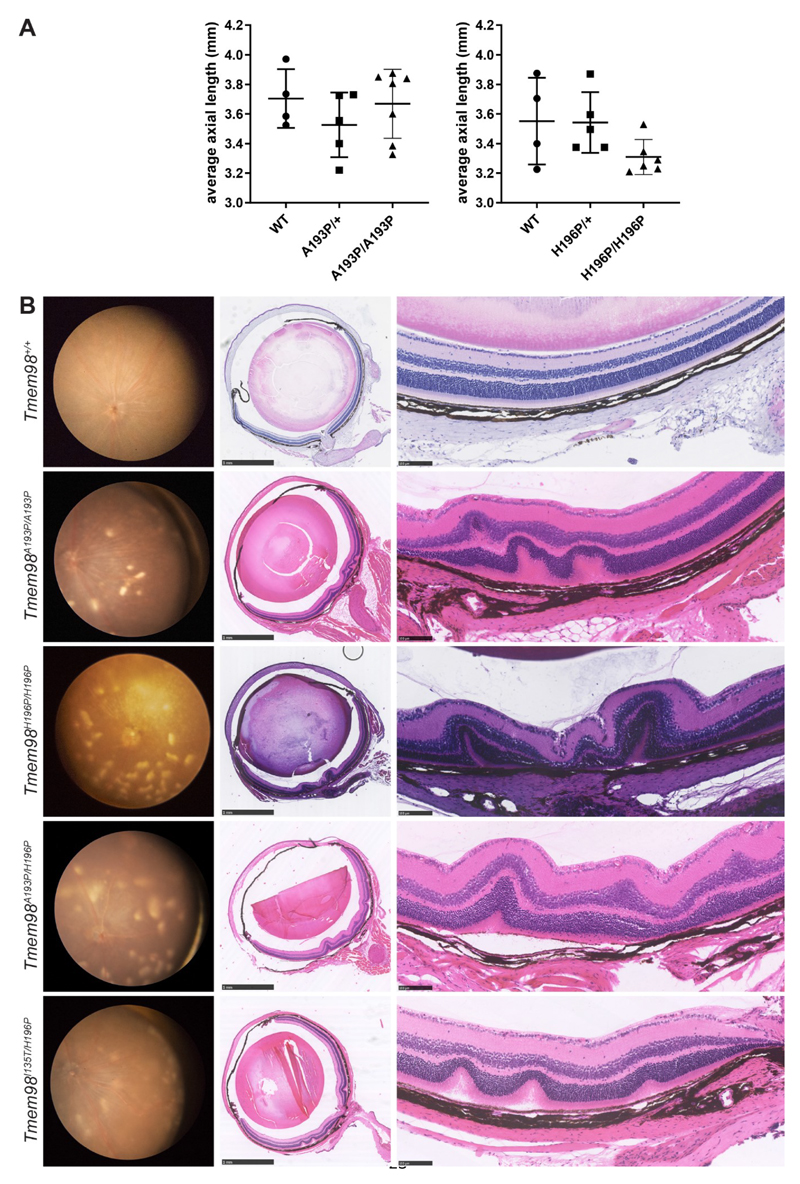

Figure 2.

Eye phenotypes of homozygous and compound heterozygous mice with missense mutations of Tmem98. (A) Axial length measurements. Shown are the average axial length measurements for each mouse. (B) Left panel, retinal images; centre panel sections through the optic nerve; right panel, higher magnification pictures of the retina. Tmem98A193P/A193P, Tmem98H196P/H196P,Tmem98A193P/H196P and Tmem98I135T/H196P retinas all have scattered white spots (left panel) and folds in the outer nuclear layer and sometimes the inner retinal layers as well (centre and right panels). Scale bars: 1 mm (B, centre panel), 100 μM (B, right panel).

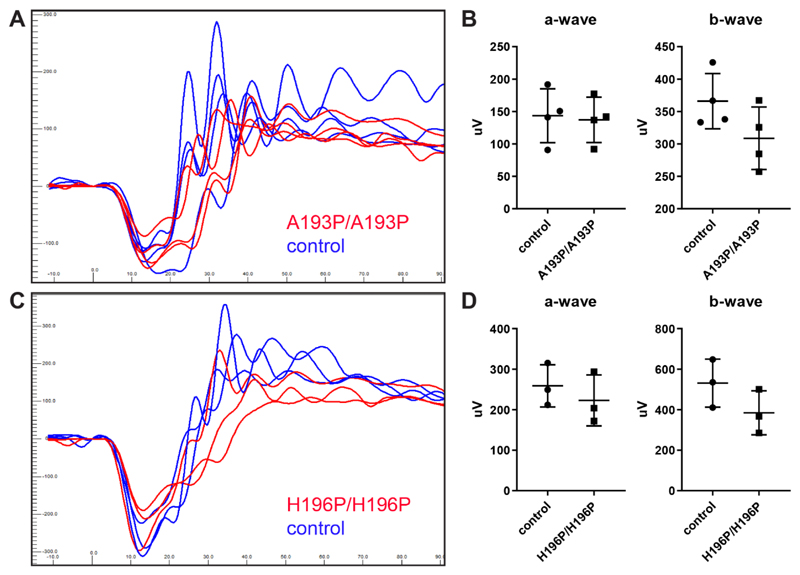

Figure 3.

Tmem98A193P/A193P and Tmem98H196P/H196P mice have a normal ERG response. (A-B) Littermates, four Tmem98A193P/A193P mice and four control mice (two wild-type and two Tmem98A193P/+) were tested at four months of age. (A) ERG traces of Tmem98A193P/A193P mice (red lines), and control mice (blue lines). Shown are the responses at 3 cd.s/m2 (average of 4 flashes) for the left eye. (B) Comparison of a-wave amplitudes (right) and b-wave amplitudes (left), average of left and right eye for each mouse. There is no significant difference between Tmem98A193P/A193P and control mice (a-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.82 and b-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.13). (C-D) Three Tmem98H196P/H196P mice and three control mice (two wild-type and one Tmem98H196P/+) were tested at 6 months of age. (C) ERG traces of Tmem98H196P/H196P mice (red lines), and control mice (blue lines). Shown are the responses at 3 cd.s/m2 (average of 4 flashes) for the left eye. (D) Comparison of a-wave amplitudes (left) and b-wave amplitudes (right), average of left and right eye for each mouse. There is no significant difference between Tmem98H196P/H196P and control mice (a-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.49 and b-wave, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.19).

Table 2. Tmem98Rwhs/+ intercross genotyping results.

| Age | WT | Rwhs/+ | Rwhs/Rwhs | Total | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adult | 34 | 79 | 0 | 113 | <0.0001 |

| E17.5-E18.5 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 19 | 0.3225 |

Test for significance using chi-square test

Results

Rwhs is a missense mutation of the Tmem98 gene

The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced mouse mutation retinal white spots (Rwhs) was found in a screen for dominant eye mutations 37. Mice heterozygous for the mutation have white patches on retinal imaging, apparently corresponding to folds or invaginations of the photoreceptor layers (Fig. 1A-B). Initial mapping indicated that Rwhs was located within an 8.5 Mb region of chromosome 11 37. The retinal phenotype was found on a mixed Balb/c and C3H background. When Rwhs mutant mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J strain to refine the genetic mapping, some obligate heterozygous mice had retinas with a normal appearance, indicating that the dominant Rwhs phenotype is not completely penetrant and that modifiers in the C57BL/6J strain can attenuate it (Supplementary Fig. S1A-D). Crossing Rwhs to the wild-derived CAST strain to introduce a different and diverse genetic background, restored the retinal phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S1E-F). Intercrossing of heterozygous mice produced no homozygous offspring at weaning, whereas at late gestation (E17.5-E18.5) foetuses of the three expected genotypes were present at Mendelian ratios indicating that homozygous Rwhs is perinatally lethal (Table 2) (an initial report suggesting that homozygous Rwhs mice were viable was incorrect and due to mapping errors 37). We mapped this lethal phenotype by intercrossing recombinant animals and refined the critical interval to a 200 kb region between the single nucleotide polymorphism markers rs216663786 and rs28213460 on chromosome 11. This region contains the Tmem98 gene and parts of the Myo1d and Spaca3 genes. We amplified and sequenced all the exons and flanking regions from this region from Rwhs mutant mice along with controls. In addition we captured and sequenced all genomic DNA in the candidate interval. We found only a single nucleotide change in the mutant strain compared to the strain of origin, a T to C transition, in exon 5 of Tmem98 (position 11:80,817,609 Mouse Dec. 2011 (GRCm38/mm10) Assembly (https://genome.ucsc.edu/)) (Fig. 1C). This mutation leads to the substitution of the non-polar aliphatic amino acid, isoleucine, by the polar amino acid threonine (I135T, numbering from entry Q91X86, http://www.uniprot.org). This amino acid substitution is predicted to be possibly damaging by the polymorphism prediction tool PolyPhen-242.

TMEM98 is a 226 amino acid protein annotated with a transmembrane domain spanning amino acids 4-24 close to the N-terminus (http://www.uniprot.org). It is highly conserved across species; mouse and human TMEM98 share 98.7% amino acid identity and between mouse and Ciona intestinalis, the closest invertebrate species to the vertebrates, there is 38.6% amino acid identity in which I135 is conserved (Supplementary Fig. S2). TMEM98 has been reported to be a single-pass type II transmembrane protein in which the C-terminal part is extracellular 49. TMEM98 is widely expressed and is reported to be most highly expressed in human and mouse RPE (http://www.biogps.org). We confirmed its high expression in the RPE and, within the retina, we also find expression at a lower level in the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 1D). To assess retinal function electroretinography was carried out on Tmem98I135T/+ and wild-type mice (Fig. 1E and F). There were no significant differences in the a-wave or b-wave amplitudes between the Tmem98I135T/+ and wild-type mice.

We also investigated the effect of loss-of-function of Tmem98. Heterozygous loss-of-function mice are viable and fertile and have normal retinas (Supplementary Fig. S6D and F). Matings of heterozygous mice carrying the “knock-out first” Tmem98tm1a allele produced no homozygous offspring (Supplementary Table S3) demonstrating that loss-of-function of Tmem98 is lethal. At E16.5-E17.5 the three expected genotypes were present at Mendelian ratios (Supplementary Table S3) and in one litter collected at birth there were three homozygotes and three wild-types indicating that lethality occurs between birth and weaning.

The Human Nanophthalmos Missense Mutations Cause a Retinal Phenotype in the Mouse

Three mutations in TMEM98 have been implicated in autosomal dominant nanophthalmos in human families 12, 13. Two are missense mutations, A193P and H196P. Both missense mutations affect amino acids that are highly conserved (Supplementary Fig. S2) Both are predicted to be probably damaging by the polymorphism prediction tool PolyPhen-242.

To investigate the effect of the two missense mutations we used CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce A193P and H196P into the mouse gene and established lines carrying each. Western blot analysis using a validated anti-TMEM98 antibody (Supplementary Fig. S3A) showed that the mutant proteins are expressed (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Heterozygous mice for both missense mutations were viable and fertile and did not exhibit any gross eye or retinal defects when examined between 5-9 months of age (Supplementary Fig. S4, Tmem98A193P/+, n=10; Tmem98H196P/+, n=19). In contrast to the Tmem98I135T and knock-out alleles, homozygotes for both the Tmem98A193P and Tmem98H196P alleles were viable and found at the expected Mendelian ratios (Supplementary Table S4). The eyes of homozygous mice do not appear to be significantly different in axial length when compared to wild-type eyes (Fig. 2A). Although the mean length of homozygous Tmem98H196P eyes is ~7% smaller than controls this does not have statistical support (P=0.1). From about 3 months of age we found that white patches developed on the retinas of the homozygous mice and on histological examination we found folds or invaginations in the retinal layers (Fig. 2B). The appearance of the white patches was progressive; at younger ages the retinas of some homozygous mice appeared normal with patches becoming apparent as they aged (Supplementary Fig. S5). In the A193P line only 6 of 7 homozygotes were found to have retinal defects at 6 months of age; the seventh developed white patches on the retina by 9 months. In the H196P line 4/20 homozygous mice that were examined between 3 and 3.5 months of age appeared to have normal retinas. We crossed the lines together to generate compound heterozygotes. All Tmem98A193P/H196P (n=4), Tmem98I135T/ A193P (n=7) and Tmem98I135T/H196P (n=5) mice examined also displayed a similar phenotype of white patches on the retina (Fig. 2B and data not shown). We also crossed Tmem98H196P mice with mice carrying a loss-of-function allele Tmem98tm1b. Compound heterozygous mice were viable and of 17 mice examined all had normal retinas except for one mouse which had three faint spots on one retina at one year of age (Supplementary Fig. S6). These results suggest that a threshold level of the mutant missense TMEM98H196P and TMEM98A193P proteins is required to elicit the formation of white patches on the retina and that the missense mutations found in the human nanophthalmos patients are not loss-of-function. Furthermore, mice heterozygous for Tmem98tm1b with a wild type allele do not have the retinal phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S6).

To assess retinal function electroretinography was carried out on Tmem98A193P/A193P, Tmem98H196P/H196P and control mice (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in the a-wave or b-wave amplitudes between the control and the mutant mice. To determine if there was any deterioration in retinal function in older mice we also tested Tmem98H196P/H196P and control mice at 9-11 months of age but again we did not find any significant differences in the a-wave or b-wave amplitudes between the control and the mutant mice (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Characterisation of the Retinal Folds Caused by the A193P and H196P Mutations

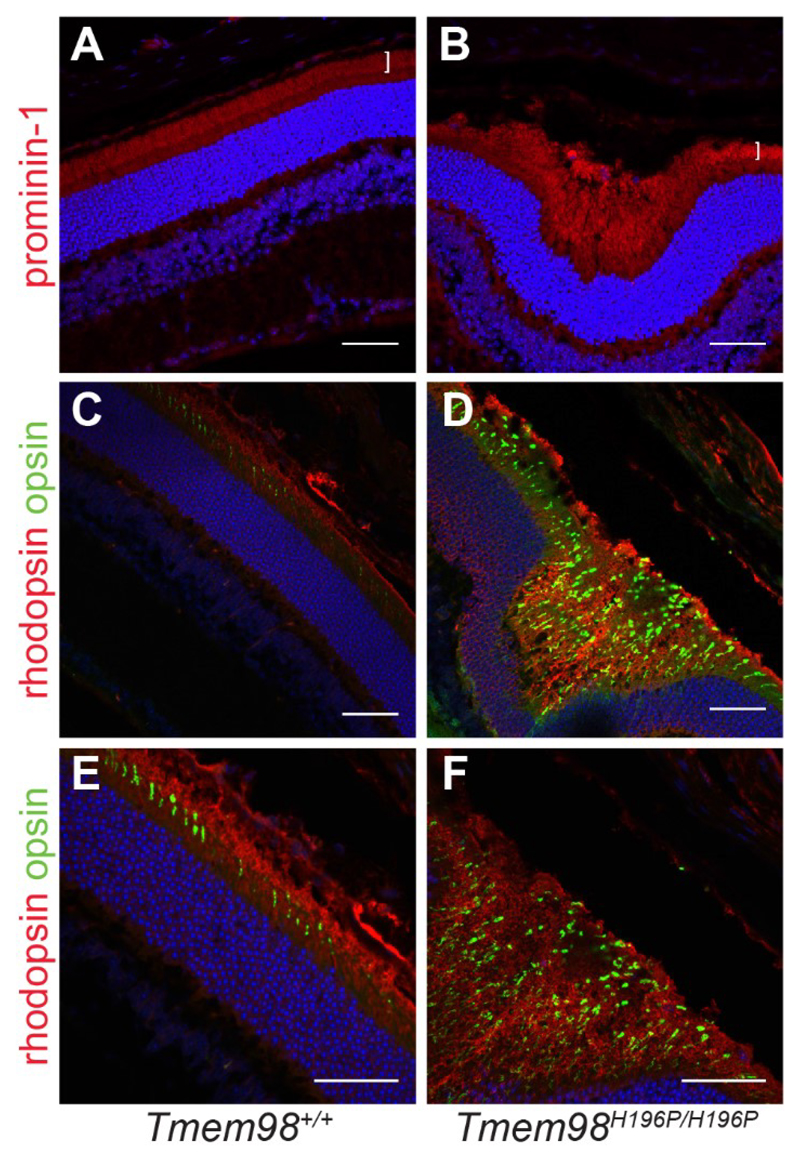

We investigated the retinal folds by immunostaining of retinal sections. We found that in the interior of retinal folds the outer segment layer is massively expanded as demonstrated by positive staining for the transmembrane protein prominin-1 and the rod and cone opsins (rhodopsin and ML opsin), indicating that the folds are filled with excess, disorganised outer segments or remnants of outer segments (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The interiors of the retinal folds found in the Tmem98H196P/H196P mutant mice are filled with excess outer segments. Immunostaining of retinal sections from wild-type mice (A, C and E) and Tmem98H196P/H196P mice (B, D and F). (A-B) Prominin-1 staining (red) shows that the outer segment layer (white bracket) is expanded in the retinal fold of the mutant (B) compared to wild-type (A). (C-F) Rhodopsin (red) and opsin (green) staining shows that the interior of the retinal fold is filled with outer segments. DAPI staining is shown in blue. Scale bars: 50 μM.

The retinal folds seen in other mutant mouse lines are accompanied by defects in the OLM. This structure is formed by adherens junctions between the Müller glia cells and the photoreceptors. We investigated the integrity of the OLM in our mutant mice by staining for β-catenin (Fig. 5A-D). In control mice and in the regions of the retinas of mutant mice unaffected by folds the OLM appeared intact. However, at the folds the OLM is clearly disrupted and gaps can be seen suggesting that cell-cell connections have been broken. Reactive gliosis indicated by upregulation of GFAP in the Müller cells is a response to retinal stress, injury or damage 50. We observed abnormal GFAP staining in the mutant retinas that was confined to the regions with folds, indicating that in these areas, but not elsewhere in the retina, there is a stress response (Fig. 5E-H, Supplementary Fig. S8A-D). We also stained for F4/80, a marker for macrophages/microglia. In the mutant retinas positive staining was found in the interior of retinal folds but not elsewhere in the photoreceptor layer (Fig. 5J-L, Supplementary Fig. S8F-H). The amoeboid shape of the positively-stained cells suggests that they are macrophages that have infiltrated into the retinal folds containing excess and disorganised outer segments and that they are phagocytosing degenerating outer segments. We did not observe melanin within the macrophages indicating that they had not engulfed pigmented RPE cells. Finally, we examined by transmission electron microscopy the ultrastructural architecture of the boundary between the RPE and outer segments (Fig. 6). For the homozygous mutants, in retinal areas without folds, the boundary between outer segments and RPE appeared normal (compare Fig. 6A with Fig. 6B and D). However, in the areas with folds the outer segments were disorganised and appeared to be degenerating, with cavities and other cellular debris apparent (Fig. 6C and 6E).

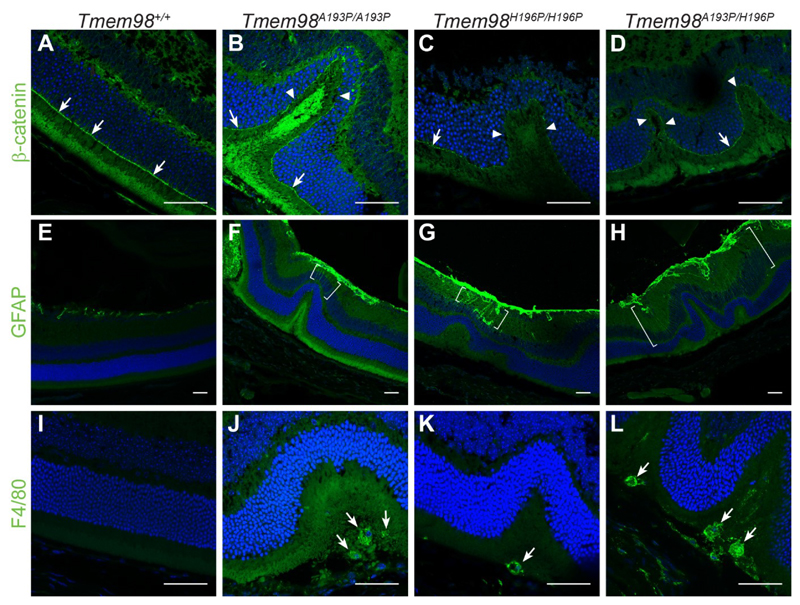

Figure 5.

Characterisation of the retinal folds in the Tmem98 mutant mice. Immunostaining of retinal sections from wild-type mice (A, E and I), Tmem98A193P/A193P mice (B, F and J), Tmem98H196P/H196P mice (C, G and K), Tmem98A193P/H196P mice (D, H and L). (A-D) β-catenin staining (green) shows that the OLM is intact in the wild-type retina and in the areas either side of folds in the mutant retinas (white arrows) but in the folds of the mutant retinas the OLM is interrupted (white arrowheads). (E-H) GFAP staining (green) is normal in the wild-type retina but above the folds in the mutant retinas there is abnormal GFAP staining extending towards the outer nuclear layer (areas between the white brackets). This indicates that in the mutants the retina is stressed in the folded regions and that retinal stress is confined to the folds. (I-L) F4/80 staining (green) reveals that macrophages have infiltrated into the areas below the folded outer nuclear layer containing excess photoreceptors in the mutant retinas (white arrows). Staining was not observed outside the folds in the mutant retinas. DAPI staining is shown in blue. Scale bars: 50 μm.

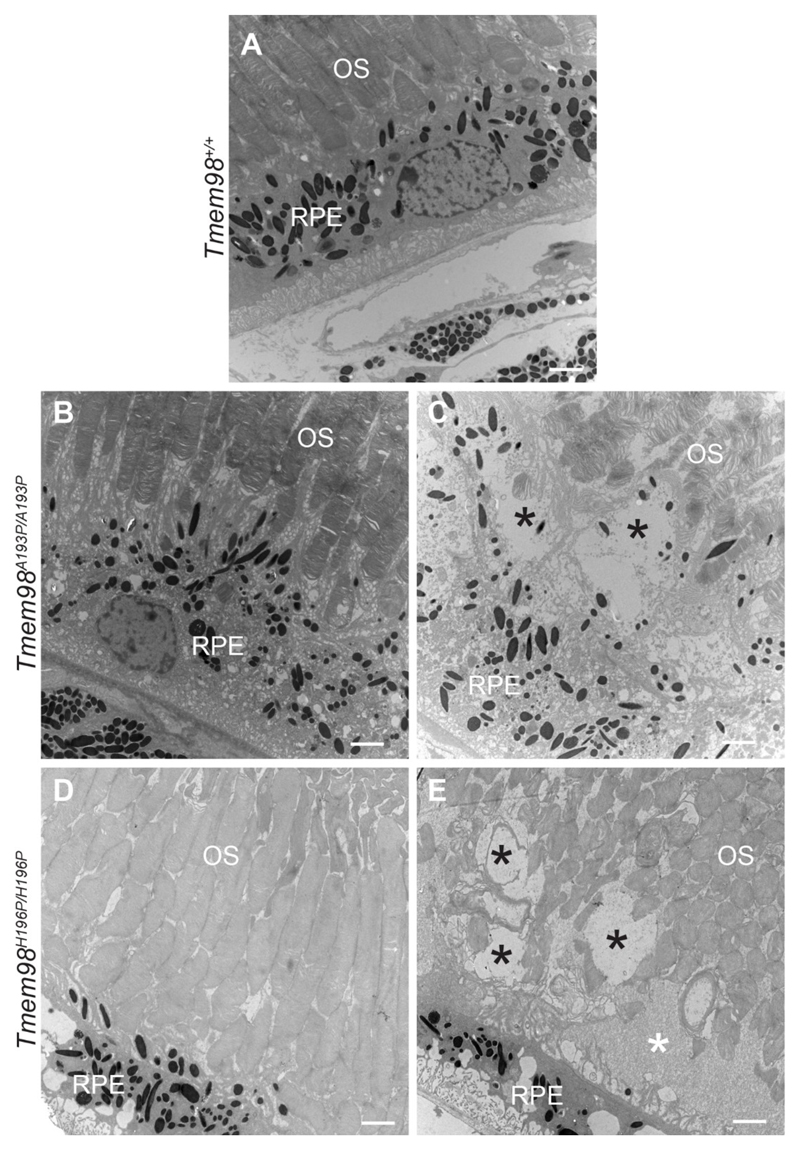

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural analysis of the RPE and outer segment boundary. (A) Wild-type mice are normal. (B and D) In mutant mice from retinal regions with no folds the outer segments adjacent to the RPE appear normal. (C and E) In retinal areas with folds the outer segments abutting the RPE appear abnormal and disorganised. Several large vacuoles (indicated by black asterisks) can be seen. In (E) there is an area containing cellular debris (indicated by a white asterisk). Tmem98A193P/A193P (B, C) and Tmem98H196P/H196P (D, E). OS = outer segments, RPE = retinal pigment epithelium. Scale bars: 2μm.

Discussion

Rwhs is Caused by a Missense Mutation in Tmem98 that is Homozygous Lethal

Here we report that the ENU-induced dominant retinal white spotting phenotype, Rwhs, is caused by an I135T missense mutation in the highly conserved transmembrane protein encoding gene Tmem98. We also found that when homozygous the Tmem98I135T allele is perinatally lethal. Tmem98 was one of the genes included in an international project to produce and phenotype knockout mouse lines for 20,000 genes 51. The targeted allele, Tmem98tm1a, was subjected to a high-content phenotyping pipeline (results available at http://www.mousephenotype.org/data/genes/MGI:1923457). It was found to be lethal pre-weaning as homozygotes, but no significant heterozygous phenotypic variation from wild-type was reported. Neither their slit lamp analysis nor our retinal examination found any eye defects in knock-out heterozygous mice (Supplementary Fig. S6D and F). We also found that Tmem98tm1a is homozygous lethal and narrowed the stage of lethality to the perinatal stage (Supplementary Table S3). This suggests that haploinsufficency for TMEM98 protein does not cause a retinal phenotype and that the I135T mutation in TMEM98 is not a loss-of-function allele but changes the protein’s function leading to the retinal white spotting phenotype.

Phenotype of Human Nanophthalmos Associated TMEM98 Missense Mutations in the Mouse

Tmem98 has been previously suggested to be a novel chemoresistance-conferring gene in hepatoceullular carcinoma 52. It has also been reported to be able to promote the differentiation of T helper 1 cells and to be involved in the invasion and migration of lung cancer cells 49, 53. Recently it has been reported that TMEM98 interacts with MYRF and prevents its autocatalytic cleavage 54. In relation to human disease two TMEM98 missense mutations, A193P and H196P, have been reported to be associated with dominant nanophthalmos 12, 13. We introduced these mutations into the mouse gene and found that mice homozygous for either, or compound heterozygous for both, developed white patches on their retinas accompanied by retinal folds, replicating the dominant phenotype found in the ENU-induced allele. We also observed for all three alleles separation of the RPE away from the neural retina in the areas under the folds. Homozygous mice for the knock-out allele do not survive after birth (Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, the two human-equivalent mutations in the mouse are homozygous viable (Supplementary Table S4), and the mouse mutation I135T, when in combination with a knock-out allele, is also viable (data not shown). Furthermore, the H196P missense mutation in combination with a gene knockout has no detectable eye phenotype and the mice are viable (Supplementary Fig. S6). This suggests that the three missense mutations described here are probably not null. It is also unlikely that the two human-equivalent recessive mutations are partial loss-of-function as when in combination with the knock-out allele they show no phenotype, rather than a more severe phenotype which would be expected for a hypomorphic allele. Likewise, this data suggests that they are not dominant negative alleles as these would be expected to exhibit a more severe phenotype when in combination with a null allele. We think it is most likely that they are gain-of-function with, in the case of H196P at least, a threshold dosage requirement. However, the phenotypes are different from the reported dominant nanophthalmos caused by the same mutations in humans and so the nature of the effect of the missense mutations on protein function will be the subject of future work.

Other genes causing nanophthalmos may also be gain of function. The serine protease PRSS56 is a recessive posterior microphthalmia or nanophthalmos mutant gene in humans, with both identified mutations affecting the C-terminus of the protein 8. The mouse mutant model of this gene, which produces a variable and slight reduction in ocular length, is a splice site mutation resulting in a truncated protein which nevertheless has normal protease activity in vitro 8. Recently the phenotype of a null allele of Prss56 has been described and it does cause some reduction in ocular size and hyperopia 36.

The mouse model of the nanophthalmos gene, Mfrp, does not reproduce the human phenotype. Rather, loss of function of this gene results in white spots apparent on retinal imaging (retinitis punctata albicans) but these have different origin from the phenotype we observe, and progress to photoreceptor degeneration. It has been reported that the Mfrp knockout mice have eyes that are slightly (but not statistically significantly) smaller, by about 2% in axial length35. Our analysis of the human-equivalent mouse Tmem98 mutations show that that neither have statistically significant size reductions, although the H196P line is ~7% shorter. It is worth noting that different strains of mice have measurably different ocular size. Strain differences of up to 2% and sex differences of over 1.5% have been reported48.

Two genes that are infrequently associated with nanophthalmos, CRB1 and BEST1, both can produce a mouse phenotype apparently indistinguishable from the one we describe here. Furthermore, the knockout mouse model of the nuclear receptor gene, Nrl, also develops retinal folds during post-natal life55. The Nrl mutant eye has defects in the outer limiting membrane (OLM), a component of which is the CRB1 protein. The Tmem98 mutations have OLM defects, but we cannot ascertain whether these defects are the primary cause of the folds or a secondary consequence.

Retinal folds are a characteristic of nanophthalmic eyes and this is usually attributed to a differential growth of neural retina within the smaller optic cup. Our data show that folds can be seen in a normal-sized eye, but we do not know whether there is nevertheless excess growth of the neural retina. The retinal defects we see are not associated with an ERG deficit, suggesting that the rest of the retina, unaffected by the folds, is functionally normal.

Notable is the detachment of the retina from the RPE within the folds. In the Nrl and Crb1 mutant eyes the photoreceptors that have lost their connection to the RPE can be seen to degenerate. We see no evidence of photoreceptor degeneration in the Tmem98 mutants. The mechanism of the pathology is still unclear. As Tmem98 is strongly expressed in the RPE, and not at all in the photoreceptors, it is likely that RPE is the affected tissue. The key observation in these and other mouse models of nanophthalmos is that the defects are focal and progressive, suggesting that secondary events exacerbate an underlying but (given ERG data) non-pathological defect. The accumulation of photoreceptor cell debris below the retinal folds suggests a focal defect in outer segment phagocytosis but one that does not lead to photoreceptor degeneration. Three of the genes associated with nanophthalmos are expressed in the RPE; Tmem98, Best1 and Mfrp. Crb1 is expressed in photoreceptors and Prss56, a secreted serine protease, is expressed in the Müller cells. It is possible that these genes interact and affect a common pathway, indeed upregulation of Prss56 has been observed in Mfrp mutants 56.

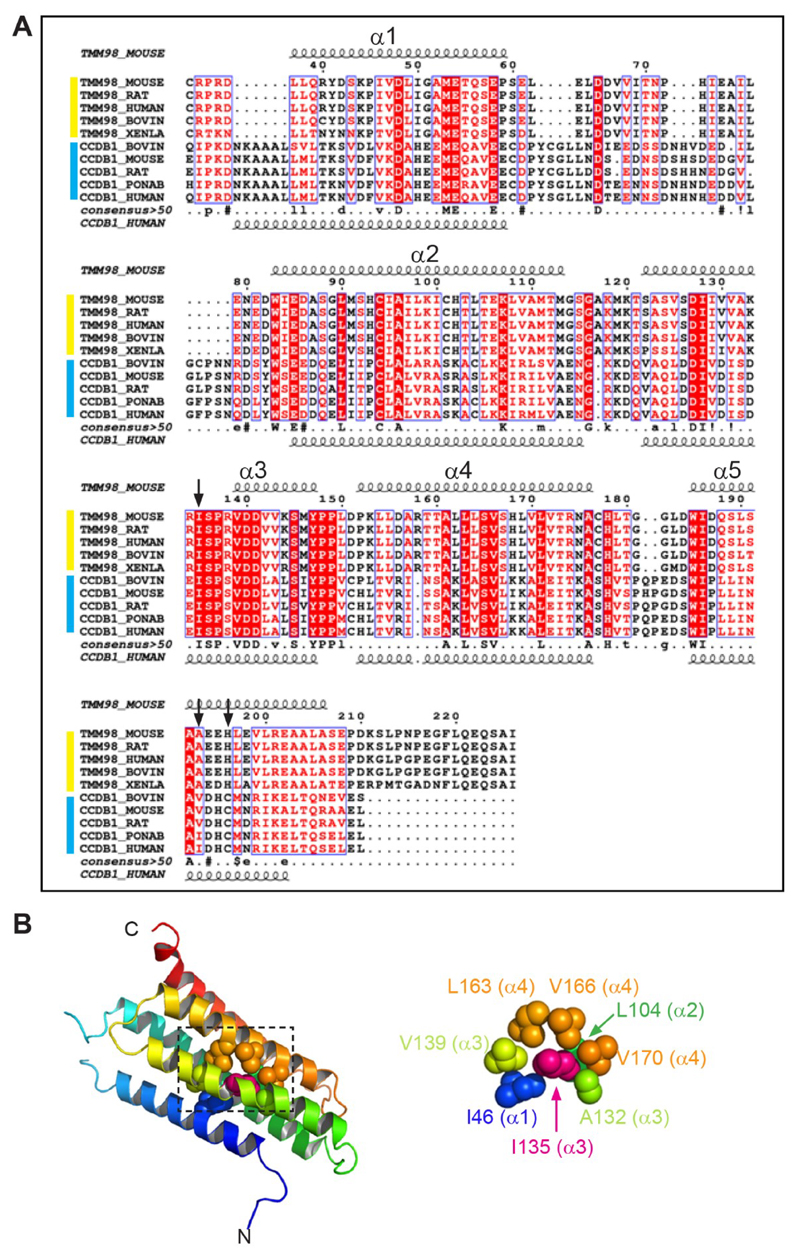

Effect on TMEM98 Protein Structure of the Missense Mutations

TMEM98 has structural homology to cyclin-D1-binding protein 1 (CCNDBP1) and contains a Grap2 and cyclin-D-interacting (GCIP) domain (pfam13324) spanning amino acids 49-152. Based upon the crystal structure of CCNDBP1, following the N-terminal transmembrane domain, TMEM98 is predicted to have a five helix bundle structure using PHYRE244 (Fig. 7A). I135 is located in the third α-helix completely buried within a sterically close-packed hydrophobic core of the domain where it has hydrophobic interactions with amino acids from four of the α-helices (Fig. 7B). SCWRL46 and FoldX47 stability calculations indicate that the Rwhs mutation T135 is only very mildly destabilising in this homology model. Its side-chain does not show steric clashes with other neighbouring atoms and its buried hydroxyl group forms a favourable hydrogen bond with the main-chain oxygen atom of A132. The stability energy calculation on the mutant TMEM98 domain structure (mean ΔΔG) is 0.28 kcal/mol (>1.6 kcal/mol is considered destabilising). The genetic evidence shows that the I135T is not loss-of-function. The detrimental effect of a mutation leading to loss of thermodynamic stability can be compensated for by the creation of novel functions57. This might be the case with the I135T mutation. The two missense mutations that are associated with nanophthalmos in humans both introduce a proline in the middle of the final α-helix of the protein which would likely lead to disruption of the secondary structure of the protein58. The recent finding that TMEM98 binds to and prevents the self-cleavage of the oligodendrocyte transcription factor MYRF54 (also highly expressed in the RPE; http://www.biogps.org) will perhaps lead to a mechanistic explanation, although the part of TMEM98 that binds to MYRF was mapped to the N-terminal 88 amino acids and a region between 55-152 amino acids was shown to be required for the cleavage inhibition. As the nanophthalmos patient-specific missense mutations are more C-terminal their effect on this reported interaction will be the subject of future work.

Figure 7.

TMEM98 protein structure and predicted effect of the I135T mutation (A) Alignment of TMEM98 proteins (yellow group) and CCNDBP1 proteins (blue group). The positions of predicted α-helices (1-5) are indicated by the curly lines. The positions of the three missense mutations are indicated by the black arrows. (B) Helical bundle based upon the crystal structure of CCNDBP1 (c3ay5A). The N- and C-terminal ends are indicated. The region surrounding I135 (dashed box) is enlarged on the right showing the hydrophobic interactions within 5 Å of I135.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Morag Robertson for help with genotyping, Craig Nicol and Connor Warnock for help with photography, the IGMM Advanced Imaging Resource for help with imaging, Edinburgh University Bioresearch and Veterinary Services for animal husbandry and MRC Human Genetics Unit scientific support services.

Grant information: funded by the MRC University Unit award to the MRC Human Genetics Unit

References

- 1.Verma AS, FitzPatrick DR. Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2007;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carricondo PC, Andrade T, Prasov L, Ayres BM, Moroi SE. Nanophthalmos: A Review of the Clinical Spectrum and Genetics. Journal of ophthalmology. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2735465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundin OH, Leppert GS, Silva ED, et al. Extreme hyperopia is the result of null mutations in MFRP, which encodes a Frizzled-related protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:9553–9558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501451102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayala-Ramirez R, Graue-Wiechers F, Robredo V, Amato-Almanza M, Horta-Diez I, Zenteno JC. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Molecular vision. 2006;12:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zenteno JC, Buentello-Volante B, Quiroz-González MA, Quiroz-Reyes MA. Compound heterozygosity for a novel and a recurrent MFRP gene mutation in a family with the nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa complex. Molecular vision. 2009;15:1794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neri A, Leaci R, Zenteno JC, Casubolo C, Delfini E, Macaluso C. Membrane frizzled-related protein gene–related ophthalmological syndrome: 30-month follow-up of a sporadic case and review of genotype-phenotype correlation in the literature. Molecular vision. 2012;18:2623. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gal A, Rau I, El Matri L, et al. Autosomal-recessive posterior microphthalmos is caused by mutations in PRSS56, a gene encoding a trypsin-like serine protease. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;88:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair KS, Hmani-Aifa M, Ali Z, et al. Alteration of the serine protease PRSS56 causes angle-closure glaucoma in mice and posterior microphthalmia in humans and mice. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:579. doi: 10.1038/ng.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orr A, Dubé M-P, Zenteno JC, et al. Mutations in a novel serine protease PRSS56 in families with nanophthalmos. Molecular vision. 2011;17:1850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiefer AK, Tung JY, Do CB, et al. Genome-wide analysis points to roles for extracellular matrix remodeling, the visual cycle, and neuronal development in myopia. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhoeven VJ, Hysi PG, Wojciechowski R, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of multiancestry cohorts identify multiple new susceptibility loci for refractive error and myopia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:314–318. doi: 10.1038/ng.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awadalla MS, Burdon KP, Souzeau E, et al. Mutation in TMEM98 in a large white kindred with autosomal dominant nanophthalmos linked to 17p12-q12. JAMA ophthalmology. 2014;132:970–977. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khorram D, Choi M, Roos BR, et al. Novel TMEM98 mutations in pedigrees with autosomal dominant nanophthalmos. Molecular vision. 2015;21:1017–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun W, Zhang Q. Does the association between TMEM98 and nanophthalmos require further confirmation? JAMA ophthalmology. 2015;133:358–359. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Leroy BP, Hoyng CB, Keunen JE, den Hollander AI. The spectrum of ocular phenotypes caused by mutations in the BEST1 gene. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2009;28:187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmorstein AD, Marmorstein LY, Rayborn M, Wang X, Hollyfield JG, Petrukhin K. Bestrophin, the product of the Best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:12758–12763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrukhin K, Koisti MJ, Bakall B, et al. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nature genetics. 1998;19:241. doi: 10.1038/915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yardley J, Leroy BP, Hart-Holden N, et al. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2004;45:3683–3689. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess R, Millar ID, Leroy BP, et al. Biallelic mutation of BEST1 causes a distinct retinopathy in humans. American journal of human genetics. 2008;82:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellikka M, Tanentzapf G, Pinto M, et al. Crumbs, the Drosophila homologue of human CRB1/RP12, is essential for photoreceptor morphogenesis. Nature. 2002;416:143. doi: 10.1038/nature721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.den Hollander AI, Jacoline B, de Kok YJ, et al. Mutations in a human homologue of Drosophila crumbs cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP12) Nature genetics. 1999;23:217. doi: 10.1038/13848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Hollander AI, Heckenlively JR, van den Born LI, et al. Leber congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa with Coats-like exudative vasculopathy are associated with mutations in the crumbs homologue 1 (CRB1) gene. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;69:198–203. doi: 10.1086/321263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson RH, Mackay DS, Li Z, et al. Phenotypic variability in patients with retinal dystrophies due to mutations in CRB1. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011;95:811–817. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.186882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zenteno JC, Buentello-Volante B, Ayala-Ramirez R, Villanueva-Mendoza C. Homozygosity mapping identifies the Crumbs homologue 1 (Crb1) gene as responsible for a recessive syndrome of retinitis pigmentosa and nanophthalmos. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2011;155:1001–1006. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paun CC, Pijl BJ, Siemiatkowska AM, et al. A novel crumbs homolog 1 mutation in a family with retinitis pigmentosa, nanophthalmos, and optic disc drusen. Molecular vision. 2012;18:2447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marmorstein LY, Wu J, McLaughlin P, et al. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1) The Journal of general physiology. 2006;127:577–589. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milenkovic A, Brandl C, Milenkovic VM, et al. Bestrophin 1 is indispensable for volume regulation in human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:E2630–E2639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418840112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Stanton JB, Wu J, et al. Suppression of Ca 2+ signaling in a mouse model of Best disease. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:1108–1118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehalow AK, Kameya S, Smith RS, et al. CRB1 is essential for external limiting membrane integrity and photoreceptor morphogenesis in the mammalian retina. Human molecular genetics. 2003;12:2179–2189. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Pavert SA, Kantardzhieva A, Malysheva A, et al. Crumbs homologue 1 is required for maintenance of photoreceptor cell polarization and adhesion during light exposure. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:4169–4177. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Pavert SA, Meuleman J, Malysheva A, et al. A single amino acid substitution (Cys249Trp) in Crb1 causes retinal degeneration and deregulates expression of pituitary tumor transforming gene Pttg1. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:564–573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3496-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kameya S, Hawes NL, Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Naggert JK, Nishina PM. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Human molecular genetics. 2002;11:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.16.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fogerty J, Besharse JC. 174delG mutation in mouse MFRP causes photoreceptor degeneration and RPE atrophy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52:7256–7266. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawes NL, Chang B, Hageman GS, et al. Retinal degeneration 6 (rd6): a new mouse model for human retinitis punctata albescens. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2000;41:3149–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velez G, Tsang SH, Tsai Y-T, et al. Gene Therapy Restores Mfrp and Corrects Axial Eye Length. Scientific Reports. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16275-8. 16151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paylakhi S, Labelle-Dumais C, Tolman NG, et al. Muller glia-derived PRSS56 is required to sustain ocular axial growth and prevent refractive error. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thaung C, West K, Clark BJ, et al. Novel ENU-induced eye mutations in the mouse: models for human eye disease. Human molecular genetics. 2002;11:755–767. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.7.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White JK, Gerdin A-K, Karp NA, et al. Genome-wide generation and systematic phenotyping of knockout mice reveals new roles for many genes. Cell. 2013;154:452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. 1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soding J. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2005;21:951–960. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nature protocols. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janson G, Zhang C, Prado MG, Paiardini A. PyMod 2.0: improvements in protein sequence-structure analysis and homology modeling within PyMOL. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2017;33:444–446. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q, Canutescu AA, Dunbrack RL., Jr SCWRL and MolIDE: computer programs for side-chain conformation prediction and homology modeling. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1832–1847. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schymkowitz J, Borg J, Stricher F, Nys R, Rousseau F, Serrano L. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:W382–388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puk O, Dalke C, Favor J, de Angelis MH, Graw J. Variations of eye size parameters among different strains of mice. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:851–857. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu W, Cheng Y, Zhang Y, et al. The Secreted Form of Transmembrane Protein 98 Promotes the Differentiation of T Helper 1 Cells. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2015;35:720–733. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis GP, Fisher SK. Up-regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in response to retinal injury: its potential role in glial remodeling and a comparison to vimentin expression. International review of cytology. 2003;230:264–290. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)30005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown SD, Holmes CC, Mallon A-M, Meehan TF, Smedley D, Wells S. High-throughput mouse phenomics for characterizing mammalian gene function. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2018;1 doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng KT, Lo CM, Guo DY, et al. Identification of transmembrane protein 98 as a novel chemoresistance-conferring gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014;13:1285–1297. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao M, Chen J, Li X, Wu Z. siRNA-TMEM98 inhibits the invasion and migration of lung cancer cells. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015;8:15661–15669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang H, Teng P, Du J, et al. Interactive repression of MYRF self-cleavage and activity in oligodendrocyte differentiation by TMEM98 protein. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2018 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0154-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stuck MW, Conley SM, Naash MI. Defects in the outer limiting membrane are associated with rosette development in the Nrl-/- retina. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soundararajan R, Won J, Stearns TM, et al. Gene profiling of postnatal Mfrprd6 mutant eyes reveals differential accumulation of Prss56, visual cycle and phototransduction mRNAs. PloS one. 2014;9:e110299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokuriki N, Stricher F, Serrano L, Tawfik DS. How protein stability and new functions trade off. PLoS computational biology. 2008;4:e1000002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barlow DJ, Thornton JM. Helix geometry in proteins. Journal of molecular biology. 1988;201:601–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.