Abstract

Objective:

The engagement of peers and service users is increasingly emphasized in mental health clinical, educational, and research activities. A core means of engagement is via the sharing of recovery narratives, through which service users present their personal history of moving from psychiatric disability to recovery. We critically examine the range of contexts and purposes for which recovery narratives are elicited in global mental health.

Methods:

We present four case studies that represent the variability in recovery narrative elicitation, purpose, and geography: a mental health Gap Action Programme clinician training program in Nepal, an inpatient clinical service in Indian-controlled Kashmir, a recovery-oriented care program in urban Australia, and an undergraduate education program in the rural United States. In each case study, we explore the context, purpose, process of elicitation, content, and implications of incorporating recovery narratives.

Results:

Within each context, organizations engaging service users had a specific intention of what ‘recovery’ should constitute. This was influenced by the anticipated audience for the recovery stories. These expectations influenced the types of service users included, narrative content, and training provided for service users to prepare and share narratives. Our cases illustrate the benefit of these co-constructed narratives and potential negative impacts on service users in some contexts, especially when used as a prerequisite for accessing or being discharged from clinical care.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice:

Recovery narratives have the potential to be used productively across purposes and contexts when there is adequate identification of and responses to potential risks and challenges.

Introduction

“Recovery narratives” – that is, publicly rendered narratives that are used for explicitly therapeutic or pedagogical purposes – have become a critical component of efforts to engage service users in mental health training and care provision. Recovery narratives generally have several purposes, which may or may not overlap, including: instructing professionals about their role in facilitating recovery, modeling recovery, promoting the narrator’s own recovery, establishing the idea that recovery is possible, and demonstrating the efficacy of a particular intervention (Jacobson, 2001). Recovery narratives are not “unconscious productions, rather, are carefully constructed and contextually situated” (Jacobsen, 2001, p. 250).

Social scientists have documented the use of recovery narratives in a range of therapeutic and legal contexts, including for asylum seekers and refugees to gain access to humanitarian benefits (Fassin & d’Halluin, 2005; Giordano, 2014; Zhang, 2016), to combat stigma around HIV/AIDS or mental illnesses (Lester, 2009; Nguyen, 2010; Shohet, 2007; Spagnolo, Murphy, & Librera, 2008; Yanos et al., 2015), to gauge positive subjective transformation during and after substance abuse treatment (Carr, 2010; Chenhall, 2007; Paik, 2006), and of course as part of formal peer support programs (Davidson et al., 2012; Solomon, 2004). In this article, we critically examine how recovery narratives are actively elicited in mental health clinical, education, and research activities globally.

Recovery narratives can be powerful tools to publicize and destigmatize diseases, empower individual sufferers, and facilitate recovery and coping. Efforts to change mental health stigma fall into three domains: knowledge-based, social contact, and protest. Most knowledge-based approaches focus on biomedical models and have shown little benefit, in some cases exacerbating prejudice and discrimination (Pescosolido, 2010). In contrast, initiatives such as Time to Change in the UK emphasize the voices of service users (Koschorke et al., 2016) and are more effective than education programs (Corrigan et al., 2012).

However, the institutional uses of recovery narratives also raise ethical questions. Anthropologists have argued that producing standard or formulaic narratives that are legible by legal or state authorities can flatten the experiences of survivors. For example, victims of human trafficking in Italy are encouraged to produce a denuncia – a legal document which initiates the filing of criminal charges against sex traffickers – in order to gain state benefits, such as rehabilitation, residency, or employment permits (Giordano, 2014). By coercing female migrants to produce “univocal autobiographical narratives” about their experience, women are not treated as “individuals with rights and privileges,” but are reduced to “the stories that the state expects to hear” in order to grant basic rights and recognition (2014, p. 11).

The contextual specificity of recovery narratives, their audience, and the social conditions in which they are elicited also have significant consequences for how we think about the relationship between recovery narratives, authenticity, and truth (Chenhall, 2007; Kornfield, 2014; Paik, 2006). For example, in institutional settings in the US, narratives are often received as a transparent form of truth. However, anthropological work shows how narratives are shaped by specific contexts, audiences, and social and cultural demands. For example, in the US, cultural and ethnopsychological orientations tend to produce particular narratives of optimism and progress through individual effort in everyday life and in clinical settings (Carr, 2010; Chang, 2001; Jenkins & Carpenter-Song, 2005; Shweder & Bourne, 1984).

We contribute to this literature by critically examining how, why, and with what consequences recovery narratives are elicited in the context of global mental health. We draw on four case studies that represent the range of contexts and purposes for which recovery narratives are used: from clinician training programs to care provision to undergraduate education. In each case study, we explore the context, purpose, process of elicitation, and content of recovery narratives, and we ultimately ask what are the benefits and harms of recovery narrative elicitation?

Case Studies

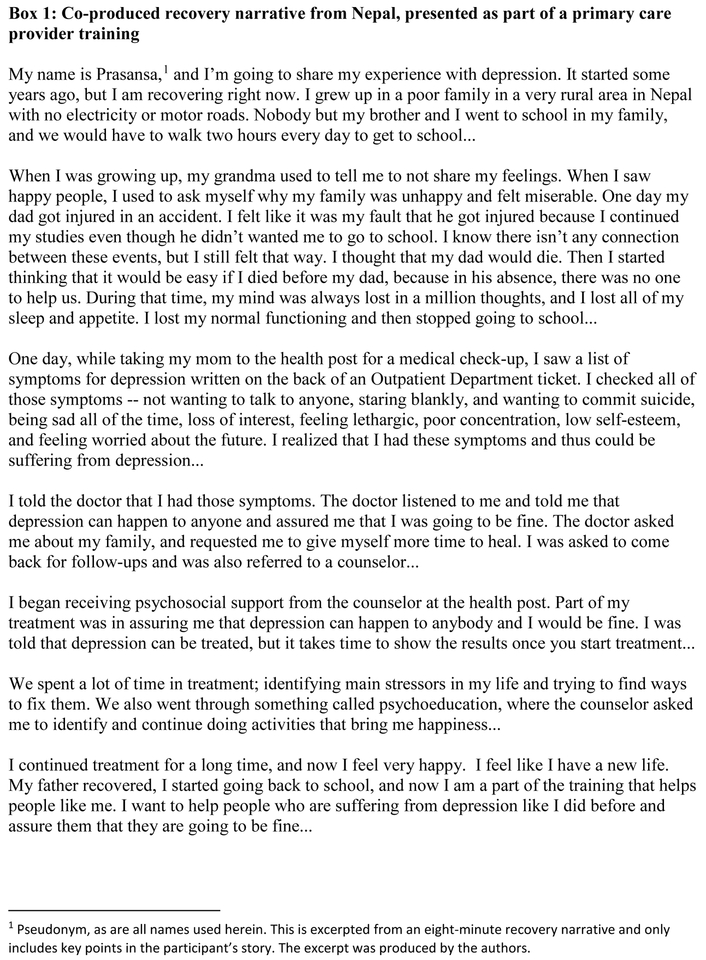

Nepal

In Nepal, as in many low-and-middle-income countries, there are increased efforts to incorporate mental healthcare into primary care settings, to address the shortage of mental health specialists. The non-profit Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal is spearheading these efforts, as part of the multi-country Programme for Improving Mental Health Care (PRIME) consortium (Jordans, Luitel, Pokhrel, & Patel, 2016; Lund et al., 2012). Primary care providers underwent 5–10 days of training, based on the World Health Organization (2016) mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP), largely consisting of didactic presentations with some role plays. As a modification of this training, (Kohrt et al., 2018; Rai et al., 2018) tested an approach in which service users delivered portions of the training, with a focus on sharing their recovery narratives, with the explicit goal of reducing stigma among providers.

Recovery narratives were elicited through an intense period of training and feedback involving a group of 12–15 service users, and were facilitated through the use of PhotoVoice. PhotoVoice is a qualitative research technique that asks participants to take photos related to a certain theme in order to provide insight into community needs and experiences (Wang & Burris, 1997). It is often used in participatory action research and at times is used to generate compelling narratives to influence policy-makers (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). Service users and caregivers were trained in PhotoVoice techniques and in the process of developing recovery narratives to share as part of clinician training. Participants then took photos in their homes and communities that represented compelling components of their recovery narrative – such as a bed where a woman spent most of her time before beginning treatment and the same bedroom with her helping her children with homework after receiving treatment. Through a 10-session process of group meetings with supervisor guidance, participants wrote their recovery narratives, rehearsed them, and received feedback for adapting them or including new photos. Service users were instructed that their narratives should not focus on symptom reduction nor try to communicate an experience of being “cured.” Rather, they were asked to describe how they live with symptoms as a valued member of society (see Box 1).

Figure 1.

Service users and caregivers then presented their final recovery narratives with accompanying photos at trainings for primary care providers. This was followed by interactive discussion and questions from healthcare providers, covering topics such as service users’ struggle with medication management, roles played by their healthcare provider, and differences in family and community reactions before and after treatment.

The inclusion of service user recovery narratives significantly reduced stigmatizing attitudes of providers, compared to trainings that did not involve service users. In interviews, providers noted increases in knowledge, empathy, and confidence in relation to mental healthcare provision, and they emphasized the positive impact of hearing personal testimony from patients. Service users described feeling that they could communicate their thoughts and experiences more easily and confidently and were glad that providers accepted them positively, without any discriminatory behavior (Rai et al., 2018).

At the same time, the study team monitored for any negative consequences of participation. Two service users withdrew from the training, as they thought that their stories would be published in the newspaper and wanted to avoid this due to fear of stigma and rejection by their community. Additionally, one young female service user reported experiencing gossip and judgment by her neighbors, who asked her family why she left home regularly to hang out at a hotel (where meetings were held). However, after the research team invited her father to accompany her to the next meeting, he was able to explain to the neighbors what she was doing, and the neighbors began asking about the training with interest (Rai et al., 2018). Involvement of family members has since become a requirement of the program.

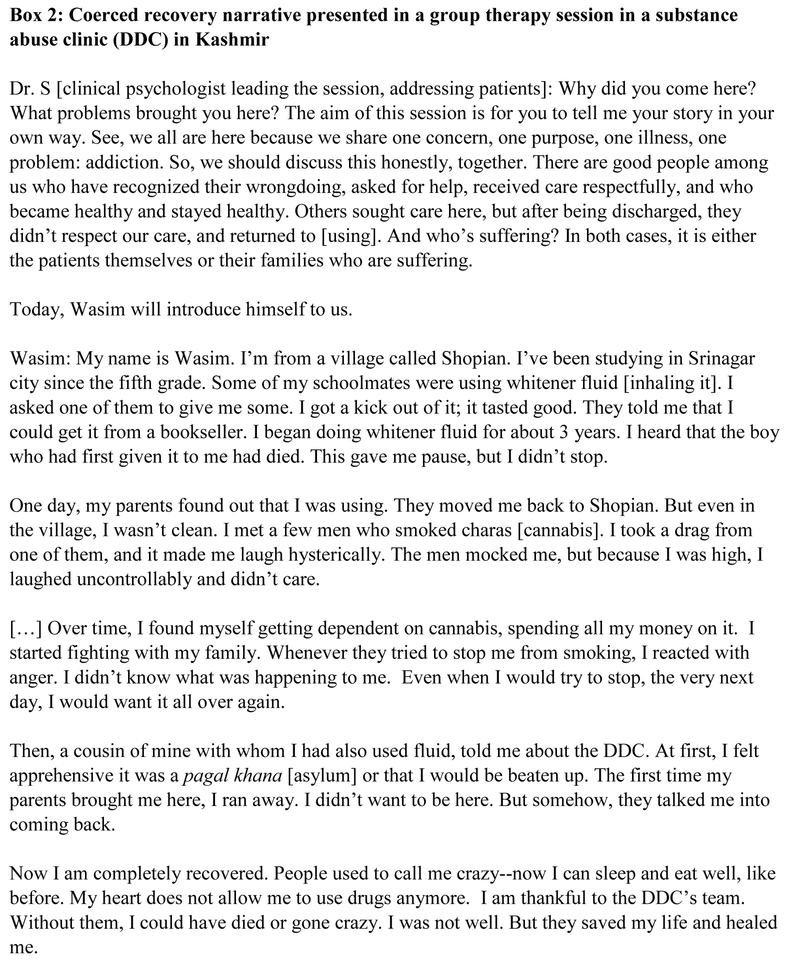

Kashmir

Indian-controlled Kashmir is the most densely militarized place on earth (Kak 2011). Since the start of an armed movement for independence from Indian rule in 1988—which was met with the imposition of draconian security and anti-terrorist legislation, large-scale militarization, and social and political violence by the Indian state—rates of mental illness, including substance abuse, have skyrocketed. According to epidemiological reports, approximately 11% of the adult male population is addicted to benzodiazepines, and more than 40% of young people report experimenting with drugs (Bhat & Imtiaz, 2017).

One of the only inpatient substance abuse centers in the state (for a population of six million) is run by the police and is located in the highly militarized police headquarters in Kashmir’s capital, Srinagar. The substance abuse clinic – called the De-Addiction Centre (DDC) – was started in 2008 as part of Indian state and military counterinsurgency efforts to “win hearts and minds” of the population after three decades of war and militarization.

While conducting ethnographic fieldwork on Kashmir’s mental health crisis (2009–2011), Varma spent 1–2 days a week at the DDC. Clinicians deployed a range of therapeutic strategies, borrowing and improvising on Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and 12-step models of substance abuse by using “local” methodologies, such as inviting imams (religious teachers) to speak on the place of addiction in Qu’ranic teachings. At the DDC, patients were required to participate in daily individual and group therapy sessions. Group therapy was a critical site for evaluating that patients had undergone positive subjective transformations and had successfully recovered from their substance abuse (Varma, 2016).

Patients who were approaching their discharge date had to tell a “recovery narrative” in order to demonstrate their sobriety and improvement as a result of inpatient treatment (see Box 2). These recovery narratives served a dual purpose. On the one hand, they helped demonstrate that patients had successfully remade themselves into new, sober persons and had cut off from harmful persons, experiences, or triggers that had led them to use drugs. On the other hand, the recovery narratives were used to teach other patients—those newer to the process of recovery—how to speak about their addiction and demonstrate positive transformation. The recovery narratives had a highly formulaic quality to them: they began with descriptions of substance use (how much money was spent, what kinds of drugs were used, how long the use went on), to low points of drug use, to finally, their time in treatment and their gratitude to the police and military establishment for curing them. Public expressions of gratitude and obeisance were especially important ways of evaluating a patient’s sincerity and wellbeing. However, because “recovery narratives,” occurred in a highly militarized space, and because the aims of the DDC were folded into the broader aims of the Indian state’s counterinsurgency project in Kashmir, they gained a different valence. The relationship between patients and doctors, and the modes of dependence generated by the recovery narrative, replicated or mirrored relations of dependency between (occupied) Kashmiris and the (occupying) Indian state more broadly. By publicly articulating their gratitude for Indian state care, patients unintentionally helped shore up the state’s counterinsurgency imperatives. Thus, recovery narratives reveal how clinical relations and treatment outcomes can have social and political reverberations.

Figure 2.

Wasim’s narrative exemplifies a trajectory of transformation: from an out-of-control user who had jeopardized relations with his family, to someone who was responsible and grateful for care. Wasim’s declaration of subjective transformation – “my heart does not allow me to abuse drugs anymore” – was attributed to the DDC. In contrast, many patients who did not successfully demonstrate this trajectory from out-of-control to grateful subject in their recovery narratives were denied discharge. However, rather than transparent outpourings of their inner feelings or demonstrations of sincerity, these public recovery narratives were pragmatic performances that patients were tacitly coerced to give. “Recovery narratives” contrasted with the more cynical and critical perspectives of treatment, the DDC, and the police, that patients shared with me ‘behind the scenes’ (see Varma, 2016). For example, during one-on-one interviews with patients in the clinic – which were out of the earshot and purview of clinicians – patients expressed ambivalent feelings towards being treated by a highly mistrusted public institution (the police). In private, they also told narratives about their histories of substance abuse that were very different from public recovery narratives, ones that did not establish a radical break between past and present, but which revealed their continued entanglements with forms of intoxication – substance abuse, but also love affairs – that they saw as entangled (see Varma, 2016).

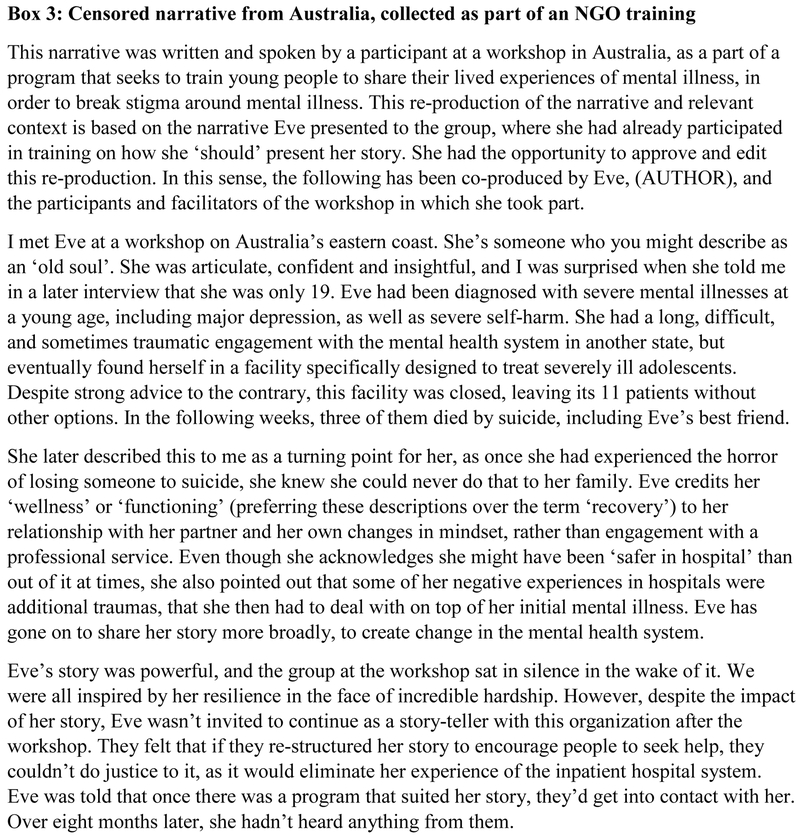

Australia

As part of an ethnography of mental healthcare sites in urban and regional Australia, Sareff (2017) studied a non-profit that trains service users to share their stories in public. This sharing of recovery narratives is explicitly aimed at encouraging sufferers listening in the audience to seek professional mental health services if they need them. The co-production of these narratives occurs through a two-day workshop, held over a weekend, that is open to any young person (aged 18–30) with a lived experience of mental illness.

In these workshops, service users receive training on self-care and how to tell stories that are safe and effective. Specifically, they are taught that stories shouldn’t discuss self-harm or suicide in detail or using specific words. Additionally, their stories should fit into a structure that reflects a recovery journey with a beginning, middle, and positive ending. Participants are also instructed to speak positively about seeking mental health services. This expectation is in place so that their narratives will not discourage listeners from seeking help; however, it creates complications for participants with largely negative experiences of mental health services.

At the end of the first day, participants share their narratives with the group, then are given feedback by the workshop facilitators on how they can improve their narratives. This process is repeated the second day. After the workshop, some participants are invited to continue their training and become speakers, while many are not. The workshop organizers do not tell participants that their stories “aren’t good enough,” as they are committed to an ideal that all authentic stories are equally valid. However, the lack of explanation leaves the process of speaker selection unclear, and the overall workshop experience unresolved, for the participants whose stories are not deemed appropriate for them to continue with the organization.

Additionally, the editing and restructuring of narratives along specific guidelines result in a loss of diversity in recovery narratives that communities have access to. The only stories that the organization is willing to give a broad platform are ones that meet their criteria as “safe” or “risk-free” and “effective.” For the non-profit, “risk-free” refers to the idea that stories are only acceptable when participants share them in a way that prevents any distress to listeners, and “effective” means they reflect well on mental health services and encourage listeners to seek help. The workshop series is a part of a broader movement in Australia that seeks to censor both fictional and non-fictional accounts of mental illness in pursuit of stories that meet these criteria as “risk-free.” There is a clear tension in the way organizations enact these values: while they feel that narratives cannot be explicitly censored, as that would contradict an expressed value that lived experiences are inherently valid when shared authentically, they must ensure “risk-free” and “effective” narratives. The de facto censorship that results limits the critical power of survivors’ personal narratives, as they are selected and edited to only reflect positively on the mental health system in Australia (see Box 3).

Figure 3.

There are many reasons why participants choose to come to these workshops. Most notable is their desire, like Eve’s, to transform their experiences into something meaningful. For them, if their negative experiences can encourage listeners to seek help, this creates a positive consequence from their illness and transforms it into something meaningful. Ultimately, in an effort to manage cultural concerns around risk, effective narratives, and authenticity, the workshops constrain participants’ ability to create meaningful narratives and limits the capacity for their narratives to show diversity and create change.

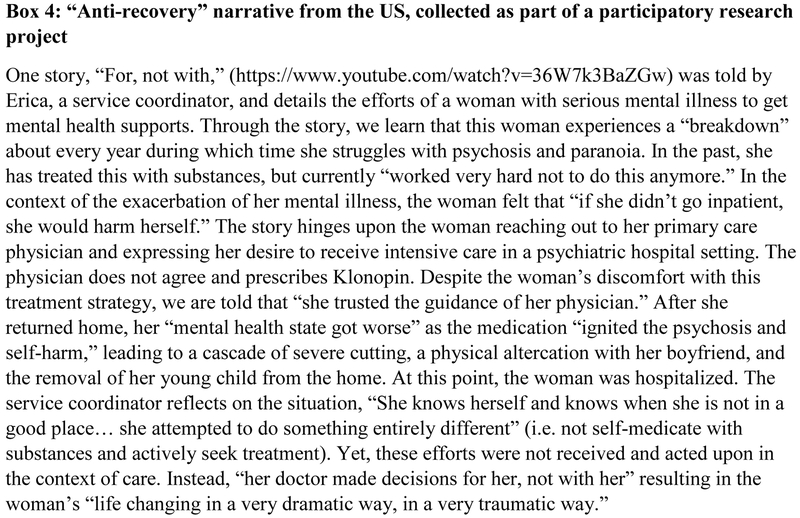

United States

Since 2016, Carpenter-Song has led the project, “Mental Health at the Margins” (MHM), that combines anthropological methods with community engaged research techniques. The goal is to place the voices and lived experiences of people who live ‘at the margins’ in rural US communities – by virtue of poverty, mental health and substance use challenges, oppression, and stigma – at the center of designing meaningfully patient-centered mental health services. This work was built on a foundation of longitudinal ethnographic research with rural families impacted by homelessness, mental health, and substance use challenges. The research team partnered with a non-profit providing shelter, food, and after-care services in the Upper Connecticut River Valley in Vermont.

MHM included a participatory element of multimedia mental health narratives, with the goal of facilitating participants telling a personal experience related to mental health issues. The participatory approach was included to disrupt the traditional power dynamics of research and to provide a framework for participants to take an active role in studying problems and developing strategies for change that reflect the needs and values of the community (Gubrium & Harper, 2013). The research team anticipated a broad range of potential media products, including audio podcasts, multimedia slideshows, and blog style essays and also envisioned diverse potential audiences, including clinicians, students, advocates, and policymakers.

Over the course of 12 months, Carpenter-Song and her team worked collaboratively to create brief, 3–5 minute mental health narratives with 11 community service users and 6 service coordinators in the shelter setting. The stories spanned a range of experiences, as suggested by some of the titles: “Trust,” “Are you new?,” “Find my Hope,” “Permission to be Calm,” “Acceptance,” “Judgment,” Unconditional Support,” “Survival,” and “Lessons in Compassion.” These stories – co-edited by a research assistant and the participant – were drawn from a series of in-depth interviews and were intended to distill key features of the lived realities of survival and cultures of care “at the margins.” Participants engaged in the process knowing that the stories were intended to be disseminated publicly and gave informed consent to share stories across a range of educational and community settings.

Erica’s story serves as a counterpoint to a traditional “recovery narrative.” As an “anti-recovery narrative,” it brings into bold relief the social and interactive contexts that either support or – in this case—shatter possibilities for recovery. Specifically, as the story focuses on the response of a physician to a person with serious mental illness, it raises serious questions about the structure and culture of current medical services to meaningfully care for people with complex needs.

Carpenter-Song has shared this story in the context of teaching medical students. “For, not with” has been particularly effective in sparking dialogue and debate surrounding issues of caring for patients living with mental illness and surviving in poverty. The stories provide an accessible grounding in the subjective experience of patients and care providers that can then serve as a point of departure for a more nuanced discussion of the culture of medicine and structural inequalities and perhaps to spark a reimagining of the possibilities for humane and inclusive care of those on the margins.

Ethical considerations

The research described herein was approved by Nepal Health Research Council, Duke University, George Washington University, Cornell University, Macquarie University, and Dartmouth College (see Ethical Approval section for additional detail). In the Kashmir study, work in the substance abuse clinic study was also approved by clinicians and administrators. All participants gave informed consent using contextually appropriate procedures (e.g., verbal consent). Where participating/observing workshops, Sareff gained opt-in consent from participants, and only their stories were included in the research. Participants in the U.S. consented to interviews and engaged in a collaborative process of distilling and editing the content. Following this, they reviewed a written document detailing a range of specific potential dissemination avenues (e.g., publication, classroom teaching) and gave written consent to share their story. Service users in Nepal were compensated for their participation. Psychosocial counselors were available throughout the trainings in Nepal and Australia, and psychiatrists were available in Nepal. During interviews, Sareff provided the details for local support services.

Discussion

In this article, we consider case studies that represent the variability within which recovery narratives are elicited in global mental health. There is contextual variability in geographies, populations, care settings, disorders, and reasons and processes for eliciting recovery narratives. Most of the case studies relate to care delivered by non-profits, which reflects the reality of global mental health service delivery. Significantly, these stories do not capture the perspectives of peer support workers – para-professionals in mental healthcare systems who often draw upon their own recovery narratives (Myers, 2016a; Repper & Carter, 2014; Solomon, 2004) – because our focus is on elicited recovery narratives. Our attention to the creation of recovery narratives across diverse ethnographic settings raises critical questions regarding the explicit and implicit purposes of creating narratives, to whom and in what contexts narratives are shared (or not), and the consequences of creating and disseminating narratives. Below we explore the benefits and potential harms revealed through these case studies.

Support, recovery, and symbolic healing

Each of the programs highlighted in our case studies sought – and to varying extents achieved – to benefit service users concretely. Several incorporated instruction on self-care, stress management, and confidentiality. Beyond these concrete benefits, the elicitation of recovery narratives sought to produce and communicate healing at individual, interpersonal, and community levels. Anthropologists have thought deeply about how healing occurs across cultures, professions, and health conditions (cf, Csordas, 2002; Kleinman, 1988a; Mattingly and Garro, 2000). One approach has used the heuristic of symbolic healing. In symbolic healing, the healer frames suffering in a manner that is culturally salient to the person in suffering and relevant audience, such as family or community, evoking an emotional investment to the persons involved and their narrative (Dow 1986). Through emotional transformation attached to culturally salient concepts and symbols, the healer demonstrates to the individual and audience that they have moved onto a road toward recovery (Dow, 1986; Levi-Strauss, 2000). The anthropologist and psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman (1988b) describes that symbolic aspects of healing do not reside in eradication of pathology but upon the relationship in which healer and sufferer are convinced that the sufferer has changed for the better.

Assumed within efforts to achieve symbolic healing are specific cultural scripts regarding “recovery.” In Kashmir, patients must perform a recovery narrative that meets the criteria of beginning with a cultural stereotype of what it means to be a substance abuser, then going through a culturally sanctioned transformation, i.e., police enforced treatment, then experience a physical and moral recovery. In Australia, individuals whose recovery did not meet the organization’s expectations of the recovery journey in terms of behaviors (e.g., proactive help-seeking of biomedical or psychological care), were not considered to have symbolic journeys that would communicate the organizational message to convince others of being changed for the better, in Kleinman’s framing. In the U.S., expectations of recovery engage with ethnocultural orientations toward self-reliance (cf. Myers, 2015) and control (cf. Jenkins & Carpenter-Song, 2005). In the anti-recovery narrative presented, both of these dimensions of autonomy are undermined by the physician in acting “for” rather than “with” the patient.

In Nepal, symbolic healing components were explicitly embedded into the PhotoVoice process, with the goal of transforming health workers’ conceptions about recovery from mental illness. PhotoVoice presentations described a healing journey using culturally salient images (i.e., symbols) related to suffering, value in society, and healing, paired with humanizing descriptions of their personal relationships, life goals, and daily routines. Health workers in the training could invest emotionally in these stories and conceptualize their primary care clinics as spaces of recovery. Recovery narratives were intended to recreate the process of symbolic healing, such that health workers left the training more emotionally invested in the belief that mental illness could be successfully treated in their primary care health facilities.

The anthropological framing of symbolic healing is also important to interpret the experience of participants in recovery narrative programs. In Nepal, participants described that both in their own self-reflection and in the eyes of family and community members, they went from being a person for whom mental illness was a liability to being a person for whom mental illness was a gateway for teaching and supporting others (Rai et al., 2018). In Australia, participants experienced symbolic healing from the transformation of their illness experiences. By using their stories of recovery to potentially help others who were in the midst of suffering, the participants could transform their illnesses into productive and positive experiences through helping others. This also transformed them as subjects into provisioners of healing rather than illness sufferers.

Confessional technologies and potential harms

Despite the potential benefits of sharing recovery narratives, there are several ways that service users could experience harm, and these risks must be carefully considered in designing programs to elicit recovery narratives. One of the first risks to consider is coercion, which is closely tied to autonomy and fear of stigma. Anthropologist Vinh-Kim Nguyen (2013) has critiqued “confessional technologies” or “practices that incite people to talk about themselves” (S441). Writing in the context of HIV counseling, Nguyen questions tendencies to view disclosure as a necessary step in the process of healing. Rather, he argues, disclosures are elicited as part of a historically and culturally specific notion of healing and facilitate access to treatment, creating conditions for coerced disclosure. In Kashmir, service users reported feeling stigmatized being forced to tell their stories. Similarly, some Nepali participants wanted to withdraw because they thought that their stories would be printed in the newspaper, despite reassurances that this was not an aspect of the PhotoVoice program. In Australia, participants in the workshop experienced social coercion to make themselves vulnerable to distress through sharing ‘authentic’ narratives, as well as being vulnerable to rejection if their stories were not considered appropriate to be shared publicly.

There is an amplified risk of coercion when recovery narratives are tied to treatment provision. In Kashmir, recovery narratives were treated as a requirement for discharge from inpatient care, creating conditions in which patients were coerced into not only sharing a narrative but one with specific features. In contrast, in the U.S., narratives were co-constructed by participants and researchers and, as such, were not tied to treatment provision. Instead, the process of constructing narratives was intended as an opportunity to comment on – and potentially critique – experiences of mental health treatment.

Nguyen also critiques tendencies to consider “confessional technologies” as culture-free reflections of some objective reality, arguing that they are instead active in constituting notions of the self. We have shown how, far from being a spontaneous outpouring of an inner state, within clinical settings, recovery narratives are renegotiated, reconstructed, and reformulated in order to demonstrate positive treatment outcomes (Chenhall, 2007). Our case studies show the range of ways that recovery narratives are co-constructed, either explicitly – such as through PhotoVoice workshops with feedback in Nepal or in the U.S. with collaborative video editing – or implicitly, such as being shaped by clinicians’ expectations in Kashmir, or at times outright censored in Australia. While self-help discourses often assume that “healthy” individuals’ speech emerges from a natural process of conveying inner states through language, there is significant expertise and labor involved in producing recovery narratives (Carr, 2010). Scholars working in substance abuse treatment programs have also shown how as 12-step programs become hybridized with social services, premises of self-reflection and epistemic authenticity may be compromised (Kornfield, 2014; Lester, 2009; Paik, 2006). Such effects are particularly clear in Kashmir, where inpatients shape their narratives based on what they think clinicians want to hear and what will enable their discharge, and in Australia, where participants are explicitly told what to include and exclude from their narratives.

Just as there is harm in making recovery narratives a requirement for treatment provision or discharge, so there is harm in forcing what Slade and colleagues (2014) call “monocultural” notions of recovery onto service users’ narratives. Recovery holds significance at many levels: recovery as lived experience (Deegan, 1996); recovery as enacting moral agency (Myers, 2016b); recovery as social movement (Anthony, 1993) and political discourse (DHHS, 2003); recovery as cultural construct (Jenkins & Carpenter-Song, 2005; Myers, 2015); recovery as measured outcome in the context of services (Shanks et al., 2013). These case studies offer insight into how, under some conditions, recovery narratives can be usefully deployed to prompt reform (e.g., stigma-reduction) while, under other conditions, such narratives become instrumental evidence for institutions to “demonstrate recovery” as already being achieved in their work. In some contexts, such as when pursuing political asylum claims, it has been suggested that one needs to demonstrate a state of “non-recovery”, as evidence to immigration judges that the threat was sufficiently severe (Goier, 2014; Spade, 2014). Close ethnographic attention to recovery narratives illuminates the multiple initial renderings of recovery from the perspective of service users, but also reveals the ways that these initially diverse renderings are forced into a narrow definition of recovery through institutional practices that reflect broader social discourse and values. In some instances (such as the censored narrative from Australia), those narratives that cannot be made to fit the required definition are discarded.

In Nepal, service users were asked to adopt a specific 3-act structure for telling their story, while in Kashmir, individuals learned the implicit “rules” regarding recovery narratives, such as including expressions of gratitude to the police. Not only do such expectations create the potential that narratives not do justice to the varied ways that recovery can be defined and experienced, but they force service users to recraft their own narratives in an overly polished way. In Nepal, some primary care workers who heard narratives in the course of a training reported that only having stories with positive personal and societal outcomes ultimately sounded “too good.” They felt would be helpful to hear more stories from persons continuing to struggle with psychiatric disability. This has led to including more narrative elements about areas of continued struggle. This suggests the need to present multiple diverse narratives with different types and stages of recovery in order to effectively engage health workers in training.

In Australia, the process of re-structuring, re-editing, or outright censoring personal recovery narratives demonstrates the power differential between the service users and persons conducting the program. Service users’ narratives underwent fragmentation and then reformation of their experiences into objects that serve a particular cultural purpose. Participants were told to fit their stories into structures that would reflect positively on a mental health recovery journey and to eliminate or post-rationalize any critiques of the Australian mental health system. This was to make their stories more “effective” in breaking stigma and encouraging help-seeking behaviors. However, they also diminished the diversity of stories being told through the program, as well as any critical potential held through the narratives. This process alienates participants from their own recovery narratives. In contrast, the “anti-recovery” narratives elicited in the rural U.S. provide space for such diversity of lived experience to be expressed. Broadening the range of narratives to include stories of negative experiences of care and the daily struggle of mental illness may encourage a more empathic understanding of mental illness and also provoke action toward needed reforms in mental healthcare delivery.

Conclusions and recommendations

Based on the case studies critically analyzed here, we make five recommendations for programs seeking to elicit recovery narratives. First, it is imperative that such narratives never be a prerequisite to care provision or discharge. It is essential that participants understand this and that participation is indeed voluntary.

Second, programs should not expect service users to present recovery narratives without adequate preparation or support structures. Such conditions can lead individuals to feel vulnerable or distressed or to withdraw (Aggarwal, 2016; James, 2007). Service users should feel supported in preparing for potential distress of reliving painful experiences, developing their narratives, ensuring proper self-care, and seeking additional support when needed.

Third, programs should be open to the diverse ways that service users experience and define recovery. They should not be forced into one understanding of recovery or de facto censored through selecting out certain recovery experiences. Care should be taken to balance this recommendation alongside the benefits of assisting service users in structuring narratives, which can help prevent traumatization, empower individuals, and more effectively enact change such as stigma reduction. While some programs will require particular narrative structuring, some training and de-stigmatization efforts are best served by representing a fuller diversity of narratives. Programs should critically consider how to balance the goals and needs of the overall intervention and of service users to best represent genuine experiences of recovery.

Fourth, context must be considered when disseminating recovery narratives, with sensitivity to audience and venue. This is particularly relevant where narratives are recorded, as they may have been produced for a particular context and may not translate smoothly into another. For example, where narratives are produced and shared within a small group setting, this needs to be considered if they are subsequently shared online.

Finally, recovery narratives should not be reified, or thought of as objective, spontaneous outpourings. They are elicited narratives, and there should be transparency regarding the process of co-creation. Instead of being treated as static representations, recovery narrative-based approaches should be treated as complementary opportunities to amplify lived experience as a part of de-stigmatization efforts. Wherever possible, opportunities should be provided for interaction between service users and the audience.

Figure 4.

Impact and Implications.

Programs engaging with mental health service users to share their recovery narratives can reduce stigma, facilitate healing, and promote engagement in mental healthcare. Yet there are risks to mitigate. Such programs should provide adequate preparation for service users, accommodate diversity of recovery experiences, be transparent regarding co-creation of narratives, attend to context, and ensure that recovery narratives are never prerequisites for discharge or other clinical decisions.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal (Suraj Koirala, Executive Manager; Nagendra Luitel, Head of Research; Dristy Gurung, Research Coordinator; Manoj Dhakal, Field Research Coordinator) and Mark Jordans (co-PI, PRIME, King’s College London). Dr. Carpenter-Song is grateful for the research assistance of Connor Gibson and community research partners at the Upper Valley Haven.

Funding:

BNK, SR, and BAK are supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH111280, K01 MH104310). SV was supported by a Social Science Research Council-International Dissertation Research Fellowship. ECS’s research was supported by a Dartmouth Synergy Community Engagement Pilot Award from the Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (1UL1TR001086–04). RS’s research was supported by the Macquarie University RTPMRES stipend. This document is an output from the PRIME Research Programme Consortium, funded by the UK Department of International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the funders.

Footnotes

Ethical approval:

The Nepal research with service users was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council, Duke University, and George Washington University. Service users and their caregivers completed written consent if literate and verbal consent with a witness if illiterate. Service users and their caregivers were compensated for their participation in the PhotoVoice training and mhGAP health worker training with transportation costs, meals, and a per diem honorarium. A psychosocial counselor was available throughout the PhotoVoice training for any experience of distress, and psychiatrists were available for any concerns of symptom relapse. Dr. Varma’s research was approved by Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board, and the substance abuse clinic study was approved by clinicians and administrators. Interviews with patients were conducted after receiving oral consent. Ms. Sareff’s research was approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee. The program that was studied provided a social worker or counsellor for the duration of the workshops to provide mental health support for the participants. Where participating/observing the workshops, RS gained opt-in consent from participants. Where participants opt-ed out, RS did not include their stories in the research. During interviews, RS provided the details for local support services for interview participants. Dr. Carpenter-Song’s project was approved by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the process of creating “mental health moments,” which were intended for public forms of dissemination. The process typically involved a series of interviews followed by a collaborative process of distilling and editing the content. Following this process, we met individually with participants to review their story and to open a second conversation regarding dissemination. Participants reviewed a written document detailing a range of specific potential dissemination avenues (e.g., publication, classroom teaching) and gave written consent to share their story

Contributor Information

Bonnie N. Kaiser, Department of Anthropology, Global Health Program, University of California San Diego.

Saiba Varma, Department of Anthropology, University of California San Diego.

Elizabeth Carpenter-Song, Department of Anthropology, Dartmouth College.

Rebecca Sareff, Macquarie University.

Sauharda Rai, The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington.

Brandon A. Kohrt, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, George Washington University.

References

- Aggarwal N (2016). Empowering people with mental illness within health services. Acta Psychopathologica, 2(4), 36. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat SA, & Imtiaz N (2017). Drug Addiction in Kashmir: Issues and Challenges. Journal of Drug Abuse, 3(3), 19. [Google Scholar]

- Carr ES. (2010). Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, & Minkler M (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37(3), 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC. (2001). Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall R (2007). Benelong’s Haven: Recovery from Alcohol and Drug Abuse within an Aboriginal Australian Residential Treatment Center. Victoria: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, & Rüsch N (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas T (2002). Body, meaning, healing. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, & Miller R (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow J (1986). Universal Aspects of Symbolic Healing - a Theoretical Synthesis. American Anthropologist, 88(1), 56–69 [Google Scholar]

- Dunn CD. (2014). ‘Then I Learned about Positive Thinking’: The Genre Structuring of Narratives of Self Transformation. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 24(2), 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C (2014). Migrants in Translation: Caring and the Logics of Difference in Contemporary Italy. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gojer J (2014). Post-traumatic stress disorder and the refugee determination process in Canada: Starting the discourse. Geneva: UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N (2001). Experiencing Recovery: A Dimensional Analysis of Recovery Narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24(3), 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AM. (2007). Principles of youth participation in mental health services. Medical Journal of Australia, 187(7), S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH, & Carpenter-Song E (2005). The New Paradigm of Recovery from Schizophrenia: Cultural Conundrums of Improvement without Cure. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 29: 379–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJ, Luitel NP, Pokhrel P, Patel V. Development and pilot testing of a mental healthcare plan in Nepal. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;208 Suppl 56:s21–8. Epub 2015/10/09. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A (1988a). The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, And The Human Condition. Basic Books. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A (1988b). Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. New York: Free Press; Collier Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Turner EL, Sikkema KJ, Luitel NP, Rai S, Singla DR, Lamichhane J, Lund C and Patel V (2018). Reducing stigma among healthcare providers to improve mental health services (RESHAPE): Protocol for a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial of a stigma reduction intervention for training primary healthcare workers in Nepal. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4(1), 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kak S (2011). Until my Freedom has Come: The New Intifada in Kashmir. New Delhi, Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfield R (2014). (Re)Working the Program: Gender and Openness in Alcoholics Anonymous. Ethos, 42(4), 415–439. [Google Scholar]

- Koschorke M, Evans-Lacko S, Sartorius N, & Thornicroft G (2017). Stigma in different cultures. In The Stigma of Mental Illness-End of the Story? (pp. 67–82). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Strauss C (2000). The effectiveness of symbols In: Littlewood R, Dein S, editors. Cultural Psychiatry and Medical Anthropology: An Introduction and Reader (pp. 162–78). New Brunswick, NJ: The Athlone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, … & Thornicroft G (2012). PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine, 9(12), e1001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C, & Garro LC (Eds.). (2000). Narrative and the cultural construction of illness and healing. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers NL (2015). Recovery’s edge: An ethnography of mental health care and moral agency. Vanderbilt University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N (2016a). Shared humanity among nonspecialist peer care providers for persons living with psychosis: Implications for global mental health. In Kohrt B, and Mendenhall E Global mental health: Anthropological perspectives, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N (2016b). Recovery stories: An anthropological exploration of moral agency in stories of mental health recovery. Transcultural Psychiatry, 53(4), 427–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VK. (2010). The Republic of Therapy: Triage and Sovereignty in West Africa’s Time of AIDS. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paik L (2006). Are You Truly a Recovering Dope Fiend? Local Interpretive Practices at a Therapeutic Community Drug Treatment Program. Symbolic Interactionism, 29(2), 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2010). “A disease like any other”? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(11), 1321–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai S, Gurung D, Kaiser B, Sikkema K, Dhakal M, Bhardwaj A, Tergesen C, and Kohrt B (2018). A service user co-facilitated intervention to reduce mental illness stigma among primary healthcare workers: Utilizing perspectives of family members and caregivers. Families, Systems, & Health, 36(2),198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repper J, & Carter T (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels A (2018). ‘This Path is Full of Thorns’: Narrative, Subjunctivity and HIV in Indonesia. Ethos, 46(1), 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sareff R (2017). The paradoxes of mental illness recovery narratives (Unpublished masters thesis). Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks V, Williams J, Leamy M et al. (2013). Measures of personal recovery: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 64, 974–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA, & Bourne E (1984). Does the Concept of the Person Vary Cross-Culturally? In Shweder A and LeVine RA, eds. Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion (pp. 158–190). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P (2004). Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spade C (2014). The ‘good’ refugee is traumatized: Post-traumatic stress disorder as a measure of credibility in the Canadian refugee determination system Thesis. Toronto: Ryerson University. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo AB, Murphy AA, & Librera LA (2008). Reducing stigma by meeting and learning from people with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31(3), 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VK. (2013). Counselling against HIV in Africa: A genealogy of confessional technologies. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15, S440–S452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma Saiba. (2016). Love in the Time of Occupation: Reveries, Longing and Intoxication in Kashmir. American Ethnologist, 43(1), 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA. (1997). PhotoVoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) – version 2.0. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, Roe D, & Lysaker P (2015). Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: A review and comparison. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q (2016). Disaster response and recovery: Aid and social change. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 40(1), 86–97. [Google Scholar]