Abstract

The term primary progressive aphasia (PPA) describes a group of neurodegenerative disorders with predominant speech and language dysfunction as their main feature. There are three main variants – the semantic variant, the nonfluent or agrammatic variant and the logopenic variant – each with specific linguistic deficits and different neuroanatomical involvement. There are currently no curative treatments or symptomatic pharmacological therapies. However, speech and language therapists have developed several impairment-based interventions and compensatory strategies for use in the clinic. Unfortunately, multiple barriers still need to be overcome to improve access to care for people with PPA, including increasing awareness among referring clinicians, improving training of speech and language therapists and developing evidence-based guidelines for therapeutic interventions. This review highlights this inequity and the reasons why neurologists should refer people with PPA to speech and language therapists.

INTRODUCTION

Progressive neurodegenerative disorders of speech and language have been reported since the late 19th century. However it was only in the last quarter of the 20th century that they were codified and fully described as the primary progressive aphasias (PPA).1–3 These were initially felt to fall mainly within the frontotemporal dementia spectrum but evidence from postmortem—and more recently from amyloid positron-emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid—studies have shown that a proportion of cases have underlying Alzheimer’s disease pathology.4

In the present diagnostic criteria there are three PPA subtypes: the semantic, the nonfluent or agrammatic, and the logopenic variants.3 While most people with primary progressive speech or language dysfunction fit within these groups, a substantial minority does not. This unclassified, or ‘not otherwise specified’ group includes those with very early clinical features not yet fulfilling diagnostic criteria, and those with a mixed picture of symptoms and signs.5

There is currently no curative treatment for PPA, and the disease progresses inexorably over time. Symptomatic pharmacological therapies have also not shown any evidence of effectiveness and many clinicians therefore tend to be nihilistic about treating people with PPA. In fact, speech and language therapists across the world have worked for many years on tailored programmes for such people with PPA, and multiple speech and language therapeutic interventions have emerged.6,7 This review brings together current approaches to managing PPA, highlighting the barriers to access to specialist speech and language therapy and suggests future priorities for developing better care.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF PPA

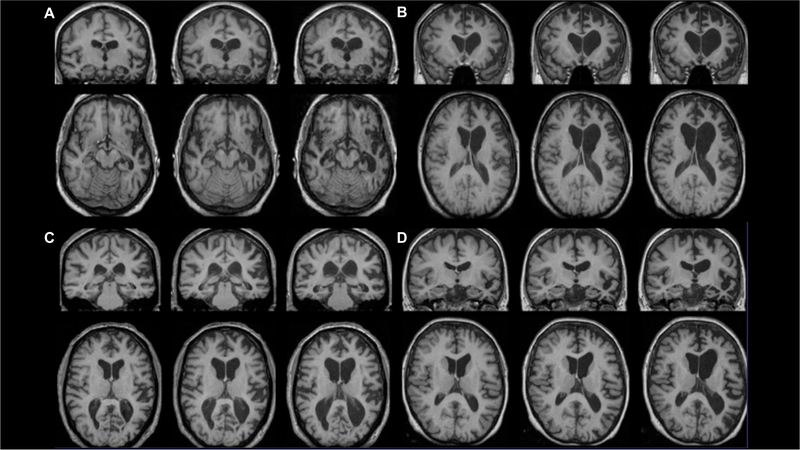

PPA is a clinical diagnosis, made with the support of neuroimaging, usually in the form of either MRI or PET (figures 1 and 2; table 1). The overarching PPA diagnosis is usually relatively clear as it requires the presence of a progressive disorder where the predominant symptom is speech and/or language dysfunction.3 In our experience, this is easier for the nonfluent and logopenic variants compared with the semantic variant which can occasionally be misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia when word-finding complaints are mistaken for ‘memory problems’. The more complex issue is usually the diagnosis of a specific PPA variant: first, it can be difficult to distinguish between the subtypes, particularly early (and conversely, very late) in the illness, and, second, some people’s problems do not fit neatly into one of the three diagnostic groups. figure 1 provides a relatively simple diagnostic algorithm for the PPA variants (see Marshall et al, 20188 for more details), table 1 describes the clinical features in more detail and figure 2 shows their classical neuroimaging features.

Figure 1.

A clinical ‘road map’ for diagnosing the PPA subtypes – adapted from Marshall et al, 2018.8 ‘Atypical’ PPA here includes the unclassified or ‘not otherwise specified’ group of patients.

lvPPA, logopenic variant; nfvPPA, nonfluent variant; svPPA, semantic variant.

Figure 2.

Classical neuroimaging features of the PPA variants. Longitudinal imaging patterns at baseline and approximately 1 year and 2 years from baseline – top row shows coronal sections and bottom row shows axial sections (left hemisphere on right of picture for both): (A) asymmetrical anteroinferior temporal lobe atrophy in semantic variant PPA, (B) asymmetrical posteroinferior frontal and insular atrophy in nonfluent variant PPA, (C) asymmetrical posterior-superior temporal and inferior parietal atrophy in logopenic variant PPA, (D) widespread left hemispheric atrophy in PPA-not otherwise specified (in this case due to a progranulin mutation).

Table 1.

Clinical and neuropsychological features of the primary progressive aphasia variants (adapted from Woollacott et al, 2016)46

| Semantic variant PPA | Nonfluent variant PPA | Logopenic variant PPA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous speech(fluency, errors, grammar, prosody) | Fluent, garrulous and circumlocutory, semantic errors, intact grammar and prosody | Slow and hesitant, Effortful +/−apraxic, phonetic errors, may be agrammatic, aprosodic | Hesitant, not effortful or apraxic, frequent word-finding pauses and loss of train of sentence, intact grammar and prosody |

| Naming | Severe anomia with semantic paraphasias | Moderate anomia with phonetic errors and phonemic paraphasias | Mild-to-moderate anomia with occasional phonemic paraphasias |

| Single word comprehension | Poor | Intact early on, but affected later in the disease | Intact early on, but affected later in the disease |

| Sentence comprehension | Initially preserved, later on becomes affected as word comprehension is impaired | Impaired if grammatically complex | Impaired, especially if long |

| Single word repetition | Relatively intact | Mild-to-moderately impaired if polysyllabic | Relatively intact (compared with sentence repetition) |

| Sentence repetition | Relatively intact | Can be effortful, impaired if grammatically complex | Impaired, with length effect |

| Reading | Surface dyslexia | Phonological dyslexia +/−phonetic errors on reading aloud | Phonological dyslexia |

| Writing | Surface dysgraphia | Phonological dysgraphia | Phonological dysgraphia |

PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

Importantly from a speech and language perspective, people with PPA may develop a motor disorder as the disease progresses. This is most common in the nonfluent variant, manifesting either as a non-specific hemiparkinsonian syndrome or a disorder resembling progressive supranuclear palsy or a corticobasal syndrome. Consequently, some patients also develop an associated dysarthria, and, over time, dysphagia.

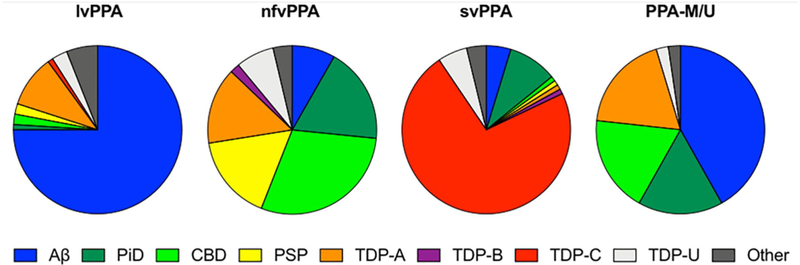

PPA is pathologically and genetically heterogeneous (figure 3). Most semantic variant PPA cases are associated with neuronal inclusions containing the TDP-43 protein, while the nonfluent variant is usually associated with tau inclusions. The logopenic variant is most commonly an atypical form of Alzheimer’s disease, with postmortem findings of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Each variant is generally sporadic but a small proportion are genetic—particularly among nonfluent cases (probably less than 5%) as well as several with PPA-not otherwise specified—typically with progranulin gene mutations. It is important that these patients and their families receive appropriate genetic counselling.

Figure 3.

Clinicopathological correlations in primary progressive aphasia (adapted from Bergeron et al, 2018). Aβ is Alzheimer’s pathology; PiD is Pick’s disease, CBD is corticobasal degeneration, and PSP is progressive supranuclear palsy (all forms of tauopathy); TDP-A, TDP-B, TDP-C and TDP-U (unclassified) are all forms of TDP-43 proteinopathy. PPA-M/U here represents a mixed-unclassified variant, equivalent to the PPA-NOS group discussed in the text. lvPPA, logopenic variant; nfvPPA, nonfluent variant; NOS, not otherwise specified; svPPA, semantic variant.

SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR PEOPLE WITH PPA AND THEIR FAMILIES

(A). Impairment-based approaches

(i). Word retrieval interventions

A number of studies have demonstrated that word retrieval interventions can be helpful for people with PPA9,10: a systematic review of 39 studies suggested that both semantic and phonologically-based treatments, and in some cases combinations of both, demonstrate immediate positive gains for people with PPA.9 It is less clear how generalisable the gains are, and how long they are maintained.11 A recent systematic review examined those questions in the context of semantic word retrieval therapies across the PPA subtypes12: generalisation was more likely in the nonfluent and logopenic variants, with maintenance of gains demonstrated across all subtypes over a short time period, although degrading quickly without ongoing practice. Targeting functional, individually-tailored training sets, with pictures of participants’ own items, in both daily sessions with the clinician and home practice, as well as ongoing practice after the end of the formal treatment period, have all been found to promote relearning and maintenance.11 Ongoing research aims to identify additional components to word learning interventions that will facilitate generalisation to functional communication, for example, whether the provision of a verb or noun facilitates successful sentence production, and whether it helps to supplement spoken word retrieval treatment with written naming. figure 4 provides an example of how word retrieval interventions work using Repetition and Reading in the Presence of a Picture13.

Figure 4.

Examples of interventions used for people with primary progressive aphasia. AAC, augmentative and alternative communication.

(ii). Script training and other approaches to improving fluency

Few studies have implemented interventions to improve fluency in nonfluent variant PPA14–19 and, among those, only two have addressed the core symptoms of agrammatism14 and apraxia of speech.18 Schneider and colleagues examined a treatment for verb production in a single case with nonfluent variant PPA,14 and saw gains for treated verb tenses as well as generalised improvement on untrained verbs. Henry and colleagues implemented an oral reading treatment for apraxia of speech,18 observing generalised improvement in speech production at post-treatment, as well as relative stability in speech production over the year following treatment.

While these initial small studies documented positive outcomes, there is a need for more research investigating interventions tailored to the specific linguistic and motoric deficits that occur in nonfluent variant PPA. A new study has attempted to address this need by implementing a script training approach, designed to improve speech production and fluency in nonfluent variant PPA, documenting not only immediate response to treatment but also long-term outcomes up to 1 year after treatment.19 Script training is an established intervention technique developed in stroke aphasia/apraxia and involves repeated rehearsal, with the goal of improving automisation of production and, in turn, intelligibility and grammaticality of output. Findings so far in nonfluent variant PPA have shown significant improvement in accurate production of scripted content as well as improved overall intelligibility and grammaticality for trained topics post-treatment. Intelligibility also improved for untrained topics and gains in accurate production of trained scripts were maintained up to 1 year post-treatment. This work confirms that treatment targeting the core deficits of agrammatism and impaired motor speech can confer significant and lasting benefit to people with nonfluent variant PPA. Figure 4 provides an example of such a script.

(B). Compensatory-based approaches

There is limited research on functional communication focused interventions for people with PPA.20 The studies that have focused on such interventions have tended to examine either communication skills training21–23 or augmentative and alternative communication development or use.24–29

In contrast to the lack of research, many specialist speech and language therapists prioritise communication skills training in their management approaches with people with PPA above more impairment-based interventions in actual day-to-day clinical practice.30,31 Taking its evidence base from the post-stroke aphasia literature, this approach targets everyday use of conversation between a person with PPA and a family member or carer, and is underpinned by an assessment of strategies that facilitate communication (eg, gesture) and those that act as a barrier (eg, interruptions or abrupt topic changes).32 A recent study showed that the use of facilitative behaviours by communication partners enhanced successful conversation in semantic variant PPA,33 and there is currently work underway piloting a randomised controlled trial of a freely-available internet based resource (‘Better Conversations with PPA’) to support speech and language therapists to deliver communication training to people with PPA and their families.34

Assistive augmentative communication devices that employ both high technology (such as smart phones) and low technology (such as communication books) can support activities of daily living, such as shopping23,24 and cooking25 (see figure 4), and conversations with trained conversation partners.6,28,29 While communication books can often be quite simple reminders of everyday activities, a more detailed ‘life story book’ may facilitate improved emotional interactions between people with PPA and their partners.35 Harnessing technology to meet the complex communication needs of people with PPA provides opportunities beyond compensatory strategies. Technology could potentially help in other ways, including providing speech–language treatment via a web-based platform (eg, the Communication Bridge telemedicine platform)7,36 and using technology for leisure activities (eg, playing Solitaire online, reading a book on Kindle, etc).

(C). Group education and support

Group education and support, tailored to the needs of people with PPA and their families, can provide opportunities to practise and problem solve communication strategies with other communication partners.37 Research shows that people with PPA and their families feel valued and more confident after attending these groups.37,38 Providing information about progression of their symptoms within a group environment can provide peer support about future challenges.37 Additionally, focusing on both language and non-language based activities can enable interaction in a group setting as the person’s communication declines.38,39 table 2 lists PPA support groups across the UK, the USA and Australia.

Table 2.

Regional and national support groups across the UK, the USA and Australia

| UK | |

| Rare dementia support (which includes separate support groups for PPA (patients and carers), and all FTD disorders (carers only)) | www.raredementiasupport.org |

| Dyscover (a group for all forms of aphasia, but offers support for people with PPA and their partners) | www.dyscover.org.uk |

| USA | |

| The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration | www.theaftd.org/living-with-ftd/support-for-care-partners/ |

| Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease | www.brain.northwestern.edu/support/supportgroup/ |

| Australia | |

| The Australian FTD Association | www.theaftd.org.au/support-groups/ |

FTD, frontotemporal dementia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

(D). Therapeutic models – heading to a person-centred approach

There are several different models proposed as frameworks for structuring treatment interventions for PPA. A ‘staging’ approach offers impairment-based interventions (focusing on remediation and rehabilitation) to people in the early stages of PPA, and then providing compensatory strategies (with the goal to develop strategies to facilitate completion of a particular task) only after restoration has failed and language skills have been lost. However, such a model risks promoting generic, one-size-fits-all solutions, which do not address the complex biopsychosocial impact that PPA has on the individual and their family.40 However, in a person-centred care approach, the individual proactively informs the decisions being made about care in dynamic interactions with the clinician. Models consistent with this approach include the Life Participation Approach for Aphasia41 and the CARE Pathway model.42 Instead of a traditional ‘diagnostic assessment’ approach of administering standardised tests that focus on identifying an individual’s impairments, a ‘flip the rehab’ model starts by identifying the goals and expectations of the individual and family members, as well as the self-reported barriers to achieving their goals. This process is then followed by assessments to help document strengths and weaknesses to assist with achieving the therapy goals.

CURRENT BARRIERS TO PROVISION OF SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY SERVICES ACROSS THE UK, USA AND AUSTRALIA

So why are all people with PPA not being seen by speech and language services? It is clear that there are several barriers that limit access.

First, many people with PPA are never referred to speech and language therapy services in the first place. There may be scepticism on the part of the referrer, due to the lack of evidence that these interventions give clinically meaningful benefit in PPA. The healthcare community undoubtedly has poor awareness of the breadth of the speech and language therapist role, and the potential benefit of non-pharmacological interventions for PPA. Neurologists more often refer people with PPA to speech and language therapy than other professionals, across the UK and Australia,30,43 perhaps due to their familiarity with this profession’s role with people with post-stroke aphasia.

Second, there are limited speech and language therapy services available specifically for people with PPA. Many people are seen by speech and language therapy services that have no experience of PPA and therefore may have an inadequate assessment or management plan – specialist services are currently sparsely and inequitably distributed: a review of speech and language therapy services in the UK National Health Service (NHS) found wide geographical variation, with few available resources in some areas and many more in others.30 While most speech and language therapists receive training in graduate school on how to evaluate and provide treatment for people with stroke-induced aphasia, many do not receive formal training in the area of PPA. This sometimes leads to a lack of confidence in their ability to work with this patient group.43 Speech and language therapists without the proper training may be unaware of how to adapt evidence-based interventions for a neurodegenerative condition or how to write reimbursable goals for people with a progressive aphasia. Consequently, individuals may be discharged prematurely, rather than providing the ongoing treatment and support that people with this condition need.

Third, there has been only limited speech and language therapy research in PPA and so many interventions rely on expert evidence rather than on studies showing clear effectiveness: this has resulted in the lack of professional guidelines for speech and language therapy interventions in PPA. In the UK, the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapy position paper outlined the role of a speech and language therapist in the differential diagnosis of PPA, and in training family carers and health and social care staff, and refers the reader to the research literature on interventions. Unfortunately, the research literature underpinning this position paper is limited and while approaches described under person-centred dementia care are assumed to inform care across the dementias, commonly used therapies within such approaches—including reminiscence and life story work—have largely been developed for those with memory rather than language difficulties.44

Finally, there is the more complex issue of commissioning of services (eg, in England) and insurance reimbursement (eg, in the USA), the latter often resulting in a financial burden for people with PPA and their families. In the UK NHS, speech and language therapists are able to offer on average only four therapy sessions to people with PPA, with many services being limited to single assessment and advice sessions. In the USA, because the onset of PPA often occurs under the age of 65, many people diagnosed with this condition do not have access to their Medicare benefits for therapy services. Private insurances, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, United Healthcare, Aetna or Cigna, all have different policies in terms of their coverage of therapy for neurodegenerative conditions, with some plans stating that they do not cover ‘rehabilitation services’ for progressive conditions where symptoms will worsen over time. More positively, Medicare in the USA has recently instated an important coverage change—which is relevant for individuals with PPA—whereby ‘coverage for therapy and nursing services is based on a beneficiary’s need for skilled care, not on the ability to improve’. Also, the recent implementation of the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme is expected to break down barriers to services for those with younger onset dementia syndromes.

FUTURE PRIORITIES

Speech and language therapy services currently face the task of maximising the efficient use of limited resources in clinical practice. Restrictive referral criteria and priority schedules mean that it is not always straightforward to provide the best care. Future priorities in this area should target: (1) education for all healthcare providers on the potential benefit of speech and language therapy for people with PPA, (2) education and training for speech and language therapists across graduate school programmes regarding PPA, (3) development of a set of evidence-based speech and language therapy clinical practice guidelines for assessment and management of PPA, and (4) advocacy efforts to increase available services and insurance reimbursement for speech and language therapy for PPA, in addition to coverage of telemedicine services for this population to increase access to care.

Nearly all those with PPA can potentially benefit from person-centred speech and language therapy. It is important to identify the variables that impact the potential benefits of treatment, which may include such things as the presence of an engaged care partner in treatment sessions, motivation and anosognosia for deficits. Furthermore, it is useful to attempt to identify the ideal candidates for different approaches at each stage of disease severity. Some interventions may be difficult to test with conventional trial methods, meaning an n-of-1 trial method may sometimes be preferable. Nevertheless, research—particularly longitudinal studies with larger groups—will provide information about if and how a broad range of speech and language approaches can better meet the needs of people with PPA and their families. table 3 provides an overview of the type of studies currently available.

Table 3.

Overview of the design of speech and language therapy intervention studies in primary progressive aphasia

| Case study | Case series | Non-randomised, noncontrolled trial | Non-randomised controlled trial | Systematic review | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impairment based approaches - word retrieval therapies | |||||

| 9 | ✔ | ||||

| 10 | ✔ | ||||

| 11 | ✔ | ||||

| 12 | ✔ | ||||

| 13 | ✔ | ||||

| Impairment based approaches - script training and other approaches to improving fluency | |||||

| 14 | ✔ | ||||

| 15 | ✔ | ||||

| 16 | ✔ | ||||

| 17 | ✔ | ||||

| 18 | ✔ | ||||

| 19 | ✔ | ||||

| Compensatory-based approaches | |||||

| 20 | ✔ | ||||

| 21 | ✔ | ||||

| 22 | ✔ | ||||

| 23 | ✔ | ||||

| 24 | ✔ | ||||

| 25 | ✔ | ||||

| 26 | ✔ | ||||

| 27 | ✔ | ||||

| 28 | ✔ | ||||

| 29 | ✔ | ||||

| 32 | ✔ | ||||

| 35 | ✔ | ||||

| 7 | ✔ | ||||

| 36 | ✔ | ||||

| Group education and support | |||||

| 37 | ✔ | ||||

| 38 | ✔ | ||||

| 39 | ✔ | ||||

Speech and language therapists also require accessible evidence-based resources in this area. Developing internet-based resources such as the ‘Better Conversations with PPA’ package34 will deliver free therapy resources. Similarly the Communication Bridge telemedicine clinical trial,7 currently underway, will provide information about the effectiveness of delivering therapy remotely. There is work underway exploring those aspects that people with PPA would like speech and language therapists to research and to provide clinically, and how overall to improve quality of life for people with PPA.45 We know very little about what people with PPA and their families feel is a priority for their conversations and relationships or their support from services more generally.

CONCLUSION

People with PPA should routinely be referred for speech and language therapy interventions. Care pathways that direct physicians to refer to speech and language therapy services will provide equity of access and care. Healthcare funders should reconsider how they reimburse non-pharmacological interventions, such as speech and language therapy, which can potentially maintain people’s independence for longer. Speech and language therapists can provide a broad variety of interventions to meet the needs of people with PPA and their families. As a profession, speech and language therapists are becoming more skilled in delivering these interventions and the research literature in this area is rapidly developing. More evidence in this area will continue to reduce many of the barriers, enabling more people with PPA and their families to access evidence-based speech and language therapy.

Key points.

Nearly everyone with primary progressive aphasia has the potential to benefit from person-centred speech and language therapy.

Interventions do not ‘cure’ speech and language difficulties but they support people to be able to maintain independence for as long as possible.

Participants should be referred to speech and language therapy as early as possible on their journey to allow person-centred interventions to be collaboratively planned and developed.

Creative methods of service delivery are being explored and participants may benefit from being referred to national centres and research institutes to participate in new and evolving intervention studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Queen Square Dementia Biomedical Research Unit and the University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre; the Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre; the MRC Dementias Platform UK and the UK Dementia Research Institute. The Dementia Research Centre is an Alzheimer’s Research UK coordinating centre and is supported by Alzheimer’s Research UK, the Brain Research Trust and the Wolfson Foundation.

Funding JDR is an MRC Clinician Scientist (MR/M008525/1) and has received funding from the NIHR Rare Diseases Translational Research Collaboration (BRC149/NS/MH), the Bluefield Project and the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. JDW receives grant support from the Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research UK. ER is supported by AG055425 and AG13854 (Alzheimer Disease Core Centre) from the National Institute on Ageing. AV is funded by an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2015-08-182).

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned. Externally peer reviewed by Michael O’Sullivan, Queensland, Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol 1982;11:592–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2004;55:335–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011;76:1006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergeron D, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rabinovici GD, et al. Prevalence of amyloid-b pathology in distinct variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2018;84:729–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, et al. Classification and pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2013;81:1832–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried-Oken M, Rowland C, Gibbons C. Providing Augmentative and Alternative Communication Treatment to Persons With Progressive Nonfluent Aphasia. Perspect Neurophysiol Neurogenic Speech Lang Disord 2010;20:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogalski EJ, Saxon M, McKenna H, et al. Communication Bridge: A pilot feasibility study of Internet-based speech–language therapy for individuals with progressive aphasia. Alzheimers Dement 2016;2:213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol 2018;265:1474–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jokel R, Graham NL, Rochon E, et al. Word retrieval therapies in primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology 2014;28:1038–68. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage SA, Ballard KJ, Piguet O, et al. Bringing words back to mind: Word retraining in semantic dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012;34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry ML, Hubbard HI, Grasso SM, et al. Treatment for word retrieval in semantic and logopenic variants of primary progressive aphasia: Immediate and long-term outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadório I, Lousada M, Martins P, et al. Generalization and maintenance of treatment gains in primary progressive aphasia (PPA): a systematic review. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2017;52:543–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croot K, Raiser T, Taylor-Rubin C, et al. Lexical retrieval treatment in primary progressive aphasia: An investigation of treatment duration in a heterogeneous case series. Cortex 2019;115:133–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider SL, Thompson CK, Luring B. Effects of verbal plus gestural matrix training on sentence production in a patient with primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology 1996;10:297–317. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis M, Espesser R, Rey V, et al. Intensive training of phonological skills in progressive aphasia: a model of brain plasticity in neurodegenerative disease. Brain Cogn 2001;46:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jokel R, Cupit J, Rochon E, et al. Relearning lost vocabulary in nonfluent progressive aphasia with MossTalk Words®. Aphasiology 2009;23:175–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcotte K, Ansaldo A. The neural correlates of semantic feature analysis in chronic aphasia: Discordant patterns according to the etiology. Semin Speech Lang 2010;31:052–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry ML, Meese MV, Truong S, et al. Treatment for apraxia of speech in nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia. Behav Neurol 2013;26:77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry ML, Hubbard HI, Grasso SM, et al. Retraining speech production and fluency in non-fluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. Brain 2018;141:1799–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kindell J, Wilkinson R, Sage K, et al. Combining music and life story to enhance participation in family interaction in semantic dementia: A longitudinal study of one family’s experience. Arts Heal Publ. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray LL. Longitudinal treatment of primary progressive aphasia: A case study. Aphasiology 1998;12:651–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong SB, Anand R, Chapman SB, et al. When nouns and verbs degrade: Facilitating communication in semantic dementia. Aphasiology 2009;23:286–301. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers MA, Alarcon NB. Dissolution of spoken language in primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology 1998;12:635–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bier N, Paquette G, Macoir J. Smartphone for smart living: Using new technologies to cope with everyday limitations in semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2015:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bier N, Brambati S, Macoir J, et al. Relying on procedural memory to enhance independence in daily living activities: Smartphone use in a case of semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2015;25:913–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bier N, Macoir J, Joubert S, et al. Cooking “shrimp à la créole”: a pilot study of an ecological rehabilitation in semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2011;21:455–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cress C, King J. AAC strategies for people with primary progressive aphasia without dementia: two case studies. Augment Altern Commun 1999;15:248–59. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Góral-Półrola J, Półrola P, Mirska N, et al. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) for a patient with a nonfluent/agrammatic variant of PPA in the mutism stage. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23:182–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pattee C, Von Berg S, Ghezzi P. Effects of alternative communication on the communicative effectiveness of an individual with a progressive language disorder. Int J Rehabil Res 2006;29:151–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volkmer A, Spector A, Warren JD, et al. Speech and language therapy for primary progressive aphasia: Referral patterns and barriers to service provision across the UK. Dementia 2018;52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kindell J, Sage K, Cruice M. Supporting communication in semantic dementia: clinical consensus from expert practitioners. Quality Ageing Older Adults 2015;16:153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kindell J, Sage K, Keady J, et al. Adapting to conversation with semantic dementia: using enactment as a compensatory strategy in everyday social interaction. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2013;48:497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor-Rubin C, Croot K, Power E, et al. Communication behaviors associated with successful conversation in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Int Psychogeriatrics 2017:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volkmer A, Spector A, Warren JD, et al. The ‘Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia (BCPPA)’ program for people with PPA (Primary Progressive Aphasia): protocol for a randomised controlled pilot study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2018;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kindell J, Wilkinson R, Keady J. From conversation to connection: a cross-case analysis of life-story work with five couples where one partner has semantic dementia. Ageing Soc 2018;269:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dial HR, Hinshelwood HA, Grasso SM, et al. Investigating the utility of teletherapy in individuals with primary progressive aphasia. Clin Interv Aging. In Press 2019;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jokel R, Meltzer J, D.R. J, et al. Group intervention for individuals with primary progressive aphasia and their spouses: Who comes first? J Commun Disord 2017;66:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morhardt DJ, O’Hara MC, Zachrich K, et al. Development of a psycho-educational support program for individuals with primary progressive aphasia and their care-partners. Dementia 2017;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mooney A, Beale N, Fried-Oken M. Group Communication Treatment for Individuals with PPA and Their Partners. Semin Speech Lang 2018;39:257–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morhardt D, Weintraub S, Khayum B, et al. The CARE pathway model for dementia: Integrating psychosocial and rehabilitative strategies for care of persons with FTD disorders. J Neurochem 2016;138. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kagan A, Simmons-Mackie N, Rowland A, et al. Counting what counts: A framework for capturing real-life outcomes of aphasia intervention. Aphasiology 2008;22:258–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morhardt D, Weintraub S, Khayum B, et al. The CARE Pathway Model for Dementia: Psychosocial and Rehabilitative Strategies for Care in Young-Onset Dementias. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2015;38:333–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor C, Kingma RM, Croot K, et al. Speech pathology services for primary progressive aphasia: Exploring an emerging area of practice. Aphasiology 2009;23:161–74. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kindell J, Sage K, Wilkinson R, et al. Living with semantic dementia: a case study of one family’s experience. Qual Health Res 2014;24:401–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruggero L, Nickels L, Croot K. Quality of life in primary progressive aphasia: What do we know and what can we do next? Aphasiology 2019;33:498–519. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woollacott IOC, Rohrer JD. The clinical spectrum of sporadic and familial forms of frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem 2016;138 Suppl 1:6–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]