Abstract

Objective:

Both trauma exposure and coping are strong predictors of mental health outcomes. There is evidence that trauma and coping are linked, with cross-sectional work suggesting that individuals with more trauma exposure show poorer coping ability (i.e., more avoidance coping, less approach coping). To date, no study has examined the temporal directionality of this association, a question with important clinical implications.

Method:

Using a longitudinal dataset over four years of college (N = 787), we examined bidirectional associations between trauma exposure and three coping styles (approach, avoidance, social support-seeking). Our data analytic approach allowed us to examine both within-person and between-person effects, to better determine how change occurs at the individual level. Coping was assessed using the Brief Cope (Carver, 1997) and trauma exposure was assessed using the Traumatic Life Experiences Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000). Gender, baseline PTSD symptoms, and pre-college trauma were included as statistical control variables.

Results:

The between-person effects were consistent with the cross-sectional literature. Interestingly, rather than an increase in avoidance coping and trauma exposure over time, the within-person findings suggested an adaptive cycle over time, in which increased trauma exposure marginally predicted an increase in approach coping (B= .05, p = .07), and approach coping predicted decreased trauma exposure (B= −.07, p = .04).

Conclusions:

Our study sheds new light on how coping and stressful events may impact one another across time. Findings suggest that a focus on approach-based coping skills may be an important direction for prevention efforts.

Keywords: Coping, trauma, longitudinal, stress generation, transactional theory

Introduction

Trauma is defined in APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violation. It includes events such as natural disasters, serious accidents, sudden deaths of loved ones, or physical and sexual abuse (e.g., APA, 2013; Creamer, Burgess & MacFarlan, 2001; Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Trauma exposure has been implicated in the etiology of myriad mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder (e.g., Ball & Links, 2009; Dulin & Passmore, 2010; Hovens et al., 2010). Yet, of the 50% to 90% of those in the U.S. exposed to trauma, not all go on to experience such deleterious mental health outcomes. The identification of risk and protective factors that may serve to delineate who is at greatest risk for poor post-trauma adaptation is a mental health priority. Coping is one such factor.

The ability to cope effectively with emotional, social, and psychological challenges is a powerful determinant of longer-term mental health (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Coping strategies primarily have been classified using two approaches (Skinner et al., 2003). The first of these is an inductive approach, using statistical methods such as exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The second is a deductive approach, rationally classifying strategies based on shared characteristics. Across these methods, approach and avoidance (i.e., approaching or avoiding stressor-related emotions and experiences) are two common coping domains that have consistently emerged. Generally, approach styles are associated with better mental health outcomes and functioning, whereas avoidant coping strategies are associated with maladaptive outcomes (Taylor et al., 2007). Evidence has also emerged for a third major coping style, social support-seeking (e.g. Snell, Siegert, Hay-Smith, & Surgenor, 2011). Though the literature on this style is still nascent, the few studies that have been conducted suggest that coping by seeking out support from others is linked to better mental health outcomes (Hill, 2016; Thoits, 2011).

Importantly, trauma and coping style appear to be related, with several lines of research showing a link between increased trauma exposure and poorer coping efforts (i.e., increased avoidance coping, and/or decreased approach and social support-seeking coping) (e.g., Leitenberg, Gibson, & Novy, 2004; Vaughn-Coaxum, Wang, Kiely, Weisz, & Dunn, 2018). Yet, the temporal direction of this association has not yet been well examined. As such, whether poor coping confers risk for trauma exposure, trauma exposure leads to poorer coping, or both, is not known. This is an important question, as different etiological processes would point to distinct directions for prevention and for treatment.

Directional association between trauma and coping.

To date, much of what is known about trauma-coping associations comes from the literature on early childhood trauma. This literature has focused almost entirely on the putative unidirectional association of trauma on coping, finding that a history of childhood (i.e., emotional, physical, sexual) trauma is associated with an increased reliance on avoidance coping styles (Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Leitenberg et al., 2004; Ullman et al., 2013; Vaughn-Coaxum et al, 2018). These findings have been interpreted as evidence that coping changes for the worse, in response to trauma (e.g., McLaughlin and Lambert, 2017), a view that is consistent with frameworks such as Transactional Theory (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). It has been suggested that such changes in coping are due to neurobiological dysregulation that occurs in the face of severe stress (e.g., Marusak, Martin, Etkin, & Thomason, 2015). However, the inference that trauma impacts coping in this manner is tenuous, given that most of this work has relied on cross-sectional, retrospective designs. The absence of any assessment of pre-trauma coping in these studies precludes true examination of directionality, as temporal precedence cannot be established. Further, the near exclusive focus on early childhood traumas in this literature, with assessment of coping several years later, prevents conclusions about more temporally proximal changes in coping that might be associated with trauma. Hence, whether and how trauma exposure may influence subsequent coping is not well understood. Finally, studies on this topic have focused exclusively on between-person effects. This is problematic because, like most theories of psychological change, theories about coping (e.g., Transactional Theory) implicitly predict within-person change (Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane, & McGinley, 2014).

Importantly, studies have not examined other possibilities for how trauma and coping may be related to one another over time. Specifically, an emerging literature suggests that coping style may not only be influenced by but may also influence risk for subsequent trauma (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Brennan, & Schutte, 2005; Najdowski & Ullman, 2011), a view that is consistent with Stress Generation Theory (Hammen, Marks, Mayol, & DeMayo, 1985). That is, individuals who rely on avoidance-based coping strategies (i.e., behavioral avoidance, distraction, suppression of emotion) may be less attuned to stressors or threats in the environment, rendering them more vulnerable to trauma exposure. It is also possible that if stressors are not adequately managed, they may fester and increase in severity (e.g., an illness that is not proactively addressed).

Putting these ideas together, Moos and Holahan (2003) articulated a model in which life events, such as trauma, are bidirectionally associated with coping style. Najdowski and Ullman (2011) provided what is to our knowledge the only study to examine this theorized bidirectional relationship. These investigators studied women first sexually assaulted in late adolescence or adulthood (after age 14) and followed them for one year during adulthood. Almost half of the sample (45%) experienced another sexual assault during the one-year assessment. Those who were sexually revictimized reported using more coping strategies (approach as well as avoidance) at the second time point. The finding that both kinds of coping increased following trauma differs from the cross-sectional work described above, and suggests a new picture of trauma-coping associations. In line with Stress Generation Theory, the Najdowski and Ullman work also revealed evidence for a bidirectional effect; sexual assault victims who relied more heavily on avoidance coping styles at baseline were more likely to be revictimized one year later.

Though Najdowski and Ullman’s (2011) study offered important preliminary findings, there are limitations to the generalizability of the study, given its focus on a single trauma type (sexual revictimization) in a circumscribed risk sample (women sexually assaulted in adulthood). Further, this study examined change across only two time points over one year, precluding understanding of how these associations unfold reciprocally across time. Perhaps most importantly, Najdowski and Ullman (2011) examined only between-person effects, and thus do not capture dynamic, within-person coping processes.

The Present Study

Theoretical formulations suggest several patterns of association between trauma exposure and coping style (Hammen et al., 1983; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Moos & Holahan, 2003), which could have clinical implications for the treatment of trauma-related symptoms. For example, evidence that trauma is associated with a negative effect on coping (i.e., increases avoidance coping, and/or decreases approach coping and social support-seeking), would point to coping as a transdiagnostic mechanism by which trauma leads to vulnerability for the development of psychological disorders (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety). If, on the other hand, poorer coping predicts increased trauma exposure, this would explain why some individuals are more at-risk for experiencing trauma (see O’Donnell et al., 2017). Finally, if trauma and coping styles impact one another reciprocally, as some have suggested (Moos & Holahan, 2003), individuals exposed to trauma may be at greater risk for future re-traumatization due to increased inadequate coping. In this model, risk is cyclical, aggregating across time.

The primary aim of the present study is to examine this potential bidirectional association between trauma and coping styles. Our study utilized an empirically-derived method of classifying coping. Specifically, we examined three coping styles (approach coping, avoidance coping, social support seeking), which were derived from these data in a previous study, using EFA (Jenzer, Read, Gainey, & Prince, 2018). We used a longitudinal design with multiple time points spanning across four years in college, allowing us to model reciprocal processes. We also used a data analytic approach that disaggregates between- and within-person associations, providing a stringent test of individual coping responses following trauma, and how these responses in turn may lead to risk for re-traumatization. Our sample was comprised of emerging adults currently in college. Emerging adulthood (ages 18–25; Arnett, 2000) is a developmental period marked by significant changes in personality, the adoption of new social roles, and new responsibilities (Arnett, 2000). Further, this is a population with rates of trauma exposure that are comparable to general community samples (e.g., Read, Ouimette, White, Colder, & Farrow, 2011). For many, this period co-occurs with college attendance.

Consistent with the abundance of work showing a correlation between avoidance coping and trauma, we hypothesized that increased trauma exposure would be associated with increased avoidance coping at the subsequent year. Furthermore, consistent with Stress Generation Theory, we hypothesized that higher avoidance coping would predict higher rates of future trauma. In contrast, we hypothesized that approach coping would be protective against additional trauma exposure. Our analyses regarding social support-seeking and trauma were exploratory, as there is much less work on this coping domain.

Method

Participants and procedures

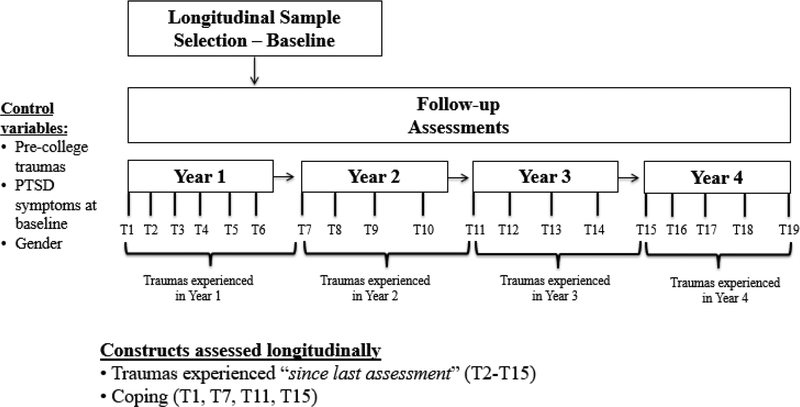

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The present study was drawn from a larger study on trauma exposure and substance use in college students (Read et al., 2011). Three cohorts of college freshmen (N = 5,885) were invited to a screening survey. Of those invited, 3,391 students completed the screening and received a $5 gift card. Those invited to the baseline survey included trauma-exposed students (n = 649) and a random sample of non-trauma-exposed students (n = 585). Of those invited, 1002 students completed the baseline and received a $25 gift card. This sample was then assessed four to six times per year for up to five additional years. Participants were compensated with gift cards for each survey completed. Figure 1. depicts a study flow chart as well as when each construct was assessed as part of the present study.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. Coping was assessed in September of every year. Traumas experienced was asked at every timepoint. Traumas across the year were summed to create a yearly total score.

Of the three cohorts included in the parent study, two (n = 787) were followed into the 4th and 5th years post-matriculation. These cohorts comprise the sample for the current study. Retention rates were high (93.2% from Year 1 to Year 2, and approximately 99% from Year 2 to Year 3 and from Year 3 to Year 4). The sample’s ethnic composition was 73.1% White (n = 576), 13.7 % Asian (n = 108), 6.1 % African American (n = 48), 3.4 % Hispanic/Latino (n = 27), and 2.8 % multi-racial or other (n = 22). At baseline, the average age was 18.11 years old (SD = 0.44) and 94% (n = 741) identified as heterosexual.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants reported on several demographic characteristics including gender, age, and ethnicity.

Trauma Exposure.

At each time point, trauma exposure was assessed using the Traumatic Life Experiences Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000; copyright 2004 by Western Psychological Services; format adapted by Jennifer P. Read, University at Buffalo, State University of New York). At baseline, participants were presented with a list of 22 traumatic events (e.g., natural disaster, motor vehicle accident, sexual assault, etc.) and asked whether they experienced each event (0 = no, 1 = yes), and if so, how many times (1 = 1 time to 6 = 5+ times). This allowed us to assess pre-college trauma exposure. For each subsequent time point (T2–T15), participants were asked “Since your last survey, have you experienced…” and presented with a reduced list of 17 Criterion A events and asked whether they experienced each event (0 = no, 1 = yes). This measure was given between 4 and 6 times a year. We created a total score for number of different types of traumas experienced each year by summing the responses across the assessments every year.

Coping.

At the start of each college year, coping strategies were assessed using the Brief Cope (Carver, 1997). From a list of 28 items, participants were asked whether they engaged in various strategies to cope with stress using response options of 1 = I usually don’t do this at all to 4 = I usually do this a lot. Prior analytic work (Jenzer et al., 2018) on this measure supports three coping factors: Approach (11 items; e.g., “I take action to try to make the situation better”), Avoidance (9 items; e.g., “I will give up trying to deal with it”), and Social Support-Seeking (5 items; e.g., “I get emotional support from others”). Higher scores represent higher use of each coping style. For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .76 to .81 for approach, .74 to .78 for avoidance, and .85 to .88 for social support-seeking.

PTSD symptoms.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed with the PTSD Checklist – Civilian version (DSM-IV version; PCL-C; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). Participants were asked how much they were bothered by 17 PTSD symptoms in the past month, with response options of 1= not at all to 5 = extremely. Sample items included “repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of the stressful experience(s),” and “avoiding activities or situations because they remind you of the stressful experience(s). The PCL-C has demonstrated good psychometric properties in non-clinical samples of college students (e.g., Conybeare, Behar, Solomon, Newman, & Borkovec, 2012). This measure shows good construct validity and correlates with gold standard PTSD interview assessments (Dobie et al., 2002). A sum score was calculated to determine PTSD severity and the Cronbach’s alpha across time points ranged from .94 to .95.

Data Analytic Strategy

Latent Curve Modeling with Structured Residuals

We examined cross-lagged associations between coping strategies and trauma using multivariate Latent Curve Modeling with Structured Residuals (LCM-SR; Curran et al., 2014). LCM-SR models include a growth model, and cross-lag model for the residual variance in the observed variables. An advantage of this modeling framework is that it imposes structure on the time-specific residuals of both coping strategies and trauma such that the time-specific residuals represent within-person variability after accounting for between-person differences in growth. This variability can be attributed to factors that lead an individual’s score to deviate from her/his expected growth trajectory (e.g., trauma at an adjacent time period predicts subsequent coping). For these reasons, LCM-SR is particularly well-suited for examining cross-lagged associations because it allows for the disaggregation of the within- and between-person effects. In our application, this allowed us to examine the dynamic influence of coping strategies in one year on trauma exposure in the subsequent year (within-person effect), accounting for typical growth in coping during this developmental period. LCM-SR also allows for the estimation of covariances among growth factors, which represent between-person associations.

We estimated our LCM-SR models in Mplus 8.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012) with full-information maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). This modeling approach allowed us to include individuals with missing data. LCM-SR models were estimated in a sequential fashion (Curran et al., 2014). Univariate growth curves were first estimated for the three coping styles and for trauma. Next structured residuals were specified and the nested chi-square test (Kline, 2005) was used to determine whether the addition of autoregressive paths for the structured residuals were supported, and if so, whether constraining the autoregressive parameters to be equal across time were supported. After specifying our univariate LCM-SR models, we estimated bivariate LCM-SR models separately for each coping style and trauma. This was done because including all coping styles in one model was too complex for estimation. Nested model tests were conducted to determine whether our bivariate LCM-SR models supported the inclusion of between-person associations in the form of growth factor covariances, and within-person associations in the form cross-lagged effects between structured residuals of coping styles and trauma exposure. Gender was a statistical control variable in all models given its association with both trauma and coping (Gavranidou & Rosner, 2003, Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002). Pre-college trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms were also included as statistical control variables because of the nature of our sample, which was selected for trauma exposure. This allowed us to distinguish current (past year) from lifetime trauma and also distinguish the emotional sequela of trauma exposure (PTSD symptoms) from trauma exposure. Further, these variables have been related to both trauma and coping in the literature (Biro, Novovic, & Gavrilov, 1997; Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, & Davis, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1. describes means and standard deviations for study variables, including the most reported trauma types. Table 2. includes bivariate correlations. For trauma variables, descriptive information is prior to log transformation. Across time points, trauma was highly skewed (Range = 3.76 to 6.78) and kurtotic (Range = 21.43 to 84.76). A log transformation was used to reduce the skew and kurtosis of trauma (skew <1.36 and kurtosis <1.57).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (Means and Standard Deviations)

| Variable | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Avoidance Coping | 1.83 (.49) | 1.80 (.51) | 1.79 (.50) | 1.78 (.51) |

| Approach Coping | 2.62 (.54) | 2.56 (.55) | 2.57 (.51) | 2.59 (.51) |

| Social Support Seeking | 2.64 (.81) | 2.60 (.81) | 2.64 (.81) | 2.69 (.82) |

| Total number of traumas | 1.78 (2.90) | .92 (1.91) | .71 (1.49) | .66 (1.27) |

| Experienced traumas | ||||

| Sudden death of loved one | .30 (.64) | .21 (.51) | .22 (.52) | .19 (.51) |

| Uninvited or wanted sexual attention | .28 (.77) | .15 (.52) | .09 (.37) | .06 (.31) |

| Loved one experience a disabling accident, assault, or illness | .27 (.72) | .16 (.48) | .13 (.45) | .09 (.38) |

| Natural Disaster | .22 (.45) | .01 (.13) | .02 (.13) | .10 (.30) |

| Being stalked, causing you to feel concerned for your safety | .16 (.52) | .06 (.29) | .04 (.26) | .03 (.18) |

| Someone threatened to cause you serious physical harm | .09 (.37) | .03 (.37) | .02 (.16) | .03 (.18) |

| Physical altercation | .09 (.46) | .05 (.30) | .03 (.23) | .03 (.21) |

| Sexual assault (i.e. Touching sexual parts against your will) | .09 (.41) | .04 (.26) | .03 (.18) | .03 (.17) |

| Life-threatening illness | .05 (.39) | .03 (.25) | .02 (.23) | .02 (.20) |

| Motor vehicle accident | .04 (.24) | .05 (.26) | .03(.21) | .02 (.15) |

| Other accidents | .04 (.18) | .02 (.20) | .02(.14) | .01 (.14) |

| Other traumas | .14 (.49) | .09 (.43) | .05 (.27) | .04 (.23) |

| PTSD symptoms | 32.43 (13.60) | - | - | - |

| Pre-college trauma | 3.17 (2.68) | - | - | - |

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Avoidance Coping Year 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Avoidance Coping Year 2 | .55** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Avoidance Coping Year 3 | .53** | .58** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Avoidance Coping Year 4 | .46** | .51** | .54** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Social support coping year 1 | .01 | −.004 | −.01 | −.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6. Social support coping year 2 | −.03 | .08* | .01 | .03 | .54** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Social support coping year 3 | .01 | .06 | .06 | .04 | .51** | .59** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8. Social support coping year 4 | .02 | −.03 | .001 | .07 | .50** | .57** | .−62** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9. Approach coping year 1 | −.18** | −.18** | −.11** | −.14** | .28** | .10** | .06 | .03 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10. Approach coping year 2 | −.19** | −.12** | −.13** | −.11** | .13** | −.27** | −.15** | .12** | .57** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11. Approach coping year 3 | −.15** | −.15** | −.11** | −.16** | .17** | .18** | .32** | .18** | .48** | .59** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12. Approach coping year 4 | −.16** | −.11** | −.10** | −.09* | .11** | .12** | .12** | .23** | .50** | .58** | .57** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13. Trauma Year 1 | .19** | .23** | .15** | .17** | .09* | .12** | .05 | .07 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .02 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 14. Trauma Year 2 | .13** | .15** | .17** | .18** | .06 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .05 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .64** | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15. Trauma Year 3 | .10** | .09* | .10** | .15** | .05 | .09* | .04 | .07 | .03 | .05 | .00 | .06 | .54** | .66** | - | - | - | - |

| 16. Trauma Year 4 | .03 | .03 | .07 | .11** | .05 | .05 | .08* | .09* | .001 | .04 | .03 | .01 | .41** | .54** | .66** | - | - | - |

| 17. Pre-college trauma | 29 ** | .23** | .17*. | .17** | .01 | −.002 | .02 | .02 | −.04 | −.004 | −.02 | −.02 | .52** | .39** | .31** | .27** | - | - |

| 18. Baseline PTSD | .44** | .37** | .27** | .25** | −.01 | −.01 | .03 | .02 | −.10** | −.05 | −.09* | −.05 | 29** | .22** | .18** | .13** | .48** | - |

| 19. Gender | −.06 | −.06 | −.05 | −.02 | −.26** | −.29** | −.35** | −.35** | .08** | .02 | .03 | .06 | −.13** | −.09* | −.07* | −.06 | −.13** | −.11** |

Correlation is significant at p < 0.01

Correlation is significant at p < 0.05

Univariate LCM-SR Models for Trauma and Coping Strategies

Trauma.

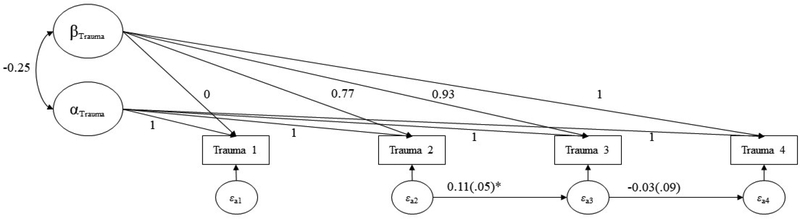

Non-linear slope factors provided the best fit for growth in trauma. Slope factor loadings were fixed for the first and fourth time points and freely estimated for the second and third time points (slope loadings of 0, 0.77, 0.93, 1 for times 1–4, respectively). The slope factor mean (M = −0.38, p <.001) was statistically significant and indicated a significant decrease in trauma over the course of college that was more rapid at the beginning of the study There was significant variability in both the intercept (σ2=0.52, p <.001) and slope (σ2= 0.41, p <.001) of trauma, suggesting significant individual differences in levels of trauma during freshman year and significant variability in change in trauma over the course of college. The intercept and slope covariance was statistically significant (covariance= −0.41, p <.001) and indicated that higher initial levels of trauma during freshman year were associated with quicker declines in trauma over the course of college. Next, structured residuals were specified, but the model converged with a warning message due to a negative residual variance for the structured residual of trauma at the first timepoint. After constraining the structured residual for trauma at the first time point to be zero, nested model tests supported the inclusion of autoregressive pathways for the residuals across time (χ2= 8.27(1), p = .004). Constraining the structured residuals to be equal across time (see Figure 2) was not supported (χ2= 4.10(1), p = .04). The final model fit the data well (χ2= 0.62(2), p = .73, CFI= 1, TLI= 1, RMSEA= .00, SRMR= .01).

Figure 2.

Univariate LCM-SR model for trauma across four time points. Coefficients from the latent slope to observed trauma variables represent slope factor loadings and the slope-intercept covariance is depicted with a double-headed arrow. β= latent slope, α= latent intercept, ε= structured residual.

Approach Coping.

In the approach coping growth model, the residual for approach coping at T1 was negative and constrained to be zero. A non-linear slope factor provided the best fit for growth with slope factor loadings fixed for the first and last timepoints (slope loadings of 0, 0.89, 1.06, 1 for times 1–4, respectively). The slope factor mean (M = −0.05, p = .005) indicated a significant decrease in approach coping over the course of college that was more rapid at the beginning of the study. There was significant variability in both the intercept (σ2= 0.30, p <.001) and slope (σ2= 0.16, p <.001), suggesting significant individual differences in approach coping during freshman year and significant variability in change in approach coping over the course of college. The intercept and slope covariance was statistically significant (covariance= −0.15, p <.001) and indicated that higher initial levels of approach coping during freshman year were associated with quicker declines in approach coping over the course of college. Next, structured residuals were estimated and nested model tests did not support the inclusion of autoregressive pathways for the residuals across time (χ2= 3.87(2), p = .14). The final model provided a strong fit to the data (χ2= 7.63(4), p = .10, CFI= .99, TLI= .99, RMSEA= .03, SRMR= .05).

Social Support-Seeking.

Linear slope factors provided the best fit for growth in social support-seeking (slope loadings of 0, 1, 2, 3 for times 1–4, respectively). The slope factor mean (M= 0.02, p = .07) was marginally significant and indicated an increase in social support-seeking over the course of college. There was significant variability in both the intercept (σ2= 0.36, p <.001) and slope (σ2= 0.02, p = .005) of social support-seeking suggesting that there were significant individual differences in social support-seeking during freshman year and significant variability in change in this coping style over the course of college. The intercept and slope covariance was not statistically significant (covariance= −0.01, p = .44). Next, structured residuals were specified, and nested model tests did not support the inclusion of autoregressive pathways for the residuals across time (χ2= 2.21(3), p = .54). The final model provided a strong fit to the data (χ2= 6.14(5), p = .29, CFI= .99, TLI= .99, RMSEA= .01, SRMR= .02).

Avoidance Coping.

Linear slope factors provided the best fit for growth in avoidance coping (slope loadings of 0, 1, 2, 3 for times 1–4, respectively). The slope factor mean (M= −0.01, p = .02) was statistically significant and indicated a significant decrease in avoidance coping over the course of college. There was significant variability in the intercept (σ2= 0.14, p <.001) and slope (σ2= 0.005, p = .03), suggesting that there were significant individual differences in maladaptive coping during freshman year and that maladaptive coping significantly decreased over the 4-year period. The intercept and slope covariance was not statistically significant (covariance= −0.01, p = .16). Next, structured residuals were specified and nested model tests did not support the inclusion of autoregressive pathways for the residuals across time (χ2= 3.93(3), p = .26). The final model provided a strong fit to the data (χ2= 4.48(5), p = .48, CFI= 1, TLI= 1, RMSEA= .00, SRMR= .03).

Summary for Univariate Models.

Results revealed declines in trauma exposure, approach coping, and avoidance coping, as well as a marginal increase in social support-seeking over the four years of college. There was significant variability for all these trajectories, suggesting that individual differences in the rate of change.

Bivariate LCM-SR Models of Coping Strategies and Trauma

Approach Coping and Trauma.

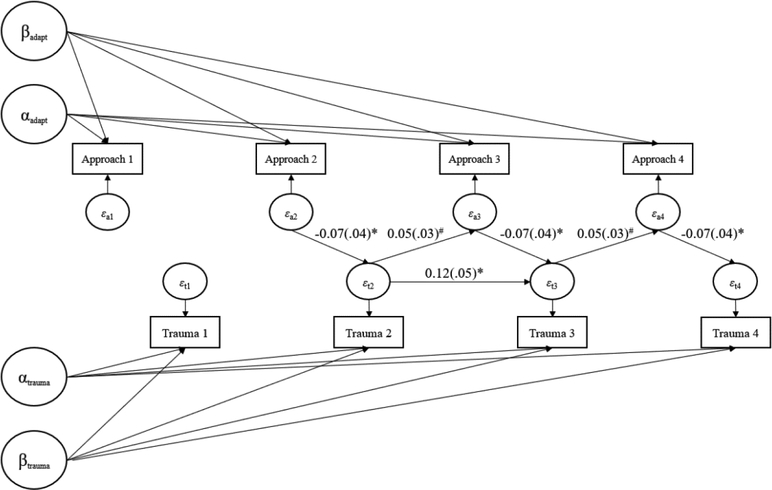

The bivariate LCM-SR model for approach coping and trauma, depicted in Figure 3, provided a good fit to the data (χ2= 41.33(32), p = .12, CFI= 1.00, TLI= .99, RMSEA= .02, SRMR= .03). Nested model tests did not support the inclusion of between-person covariances between the intercepts and growth factors for approach coping and trauma (χ2= 4.23(4), p = .37), but did support the inclusion of within-person cross-lagged paths from trauma to approach coping (χ2= 8.12(2), p = .01) and from approach coping to trauma (χ2= 12.50(3), p = .005). Further, nested model tests supported constraining the cross-lagged paths from trauma to approach coping (χ2= 0.79(1), p = .37) and from approach coping to trauma (χ2= 3.41(2), p = .18) to be equal across time. On the within-person level of analysis, trauma was marginally associated with approach coping one year later (B= .05, p = .07), such that when a college student’s trauma exposure was higher than her/his expected level of trauma given growth, levels of approach coping increased at the subsequent time point. Conversely, when a college student’s approach coping was higher than expected given growth, levels of trauma decreased one year later (B= −.07, p = .04). Gender was significantly related to the intercept of trauma (B= −.18, p <.001) and the intercept of approach coping (B= .08, p = .04), with females having significantly higher levels of trauma during freshman year and significantly lower levels of approach coping. Baseline PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with higher initial levels of trauma (B= .01, p = .003) and lower initial levels of approach coping (B= −.004, p = .01). Pre-college trauma was associated with higher levels of trauma in freshman year (B= .12, p <.001) and quicker decreases in trauma over the course of college (B= −.08, p <.001).

Figure 3.

Bivariate LCM-SR model for approach coping and trauma. Significant paths are depicted in the figure. Coefficients next to double headed arrows represent covariances and coefficients next to single headed areas represent standardized regression coefficients. Approach= approach coping, β= latent slope, α= latent intercept, ε= structured residual.

#p<.10, *p<.05.

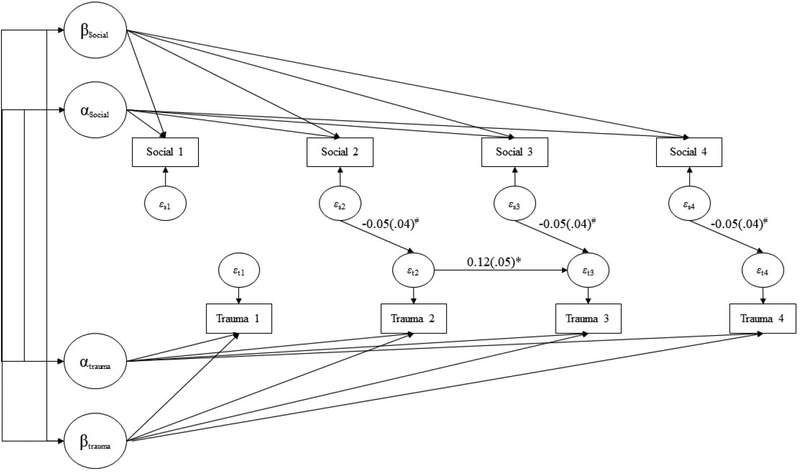

Social Support-Seeking and Trauma.

The bivariate LCM-SR model for social support-seeking and trauma, depicted in Figure 4, provided a good fit to the data (χ2= 42.56 (29), p = .05, CFI= .99, TLI= .99, RMSEA= .02, SRMR= .02). Nested model tests supported the inclusion of between-person covariances between the intercepts and growth factors for social support-seeking and trauma (χ2=22.04(4), p = .0001). High levels of trauma during freshman year were significantly associated with high levels of social support-seeking during freshman year (covariance= 0.06, p = .001) and slower increases in social support-seeking over the course of college (covariance= −.01, p = .02). High levels of social support-seeking during freshman year were significantly associated with rapid decreases in trauma over the course of college (covariance= −.04, p = .04) and the slope of trauma was significantly associated with rapid increases in social support-seeking (covariance= .02, p = .02). Nested model tests supported the inclusion of within-person cross-lagged paths from trauma to social support-seeking (χ2= 6.74(2), p = .03) and from social support-seeking to trauma (χ2= 11.91(3), p = .007). Further, nested model tests supported constraining the cross-lagged paths from trauma to social support-seeking (χ2= 2.15(1), p = .14) and from social support-seeking to trauma (χ2= 5.61(2), p = .06) across time. Trauma was not significantly associated with social support-seeking one year later (B= .04, p = .35). However, when a college student’s social support-seeking was higher than expected given her/his growth, levels of trauma marginally decreased one year later (B= −.05, p = .08). Gender was significantly related to the intercept of trauma (B= −.18, p <.001), the intercept of social support-seeking (B= −.44, p <.001), and the slope of social support-seeking (B= −.05, p = .01). Females had significantly higher levels of trauma during freshman year, significantly higher levels of social support-seeking, and significantly greater increases in social support-seeking over the course of college. Baseline PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with higher initial levels of trauma (B= .01, p = .003). Pre-college trauma was associated with higher levels of trauma during freshman year (B= .12, p <.001) and quicker decreases in trauma over the course of college (B= −.08, p <.001).

Figure 4.

Bivariate LCM-SR model for social support-seeking and trauma. Significant paths and covariances are depicted in the figure. Coefficients next to double headed arrows represent covariances and coefficients next to single headed areas represent regression coefficients. Social= Social support seeking, β= latent slope, α= latent intercept, ε= structured residual.

#p<.10, *p<.05.

Avoidance Coping and Trauma.

The bivariate LCM-SR model for avoidance coping and trauma provided an excellent fit to the data (χ2= 37.49(31), p = .19, CFI= .99, TLI= .99, RMSEA= .02, SRMR= .03). Nested model tests supported the inclusion of between-person covariances between the intercepts and growth factors for avoidance coping and trauma (χ2= 42.32(4), p <.001). In the model without covariates, between-person associations suggested that high levels of trauma during freshman year were significantly associated with high levels of avoidance coping during freshman year (covariance= 0.07, p <.001). High levels of avoidance coping during freshman year were marginally associated with quicker decreases in trauma over the course of college (covariance= −0.001, p = .05). There was a positive correlation between the slope of avoidance coping and trauma, such that a slow decrease in avoidance coping over the course of college also was associated with a slow decrease in trauma over the course of college (covariance= 0.01, p = .006). High initial levels of avoidance coping were also associated with rapid declines in trauma over the course of college (B= −.05, p <.001). Importantly, none of these covariances remained significant after including gender, pre-college trauma, and PTSD symptoms. Nested model tests did not support the inclusion of within-person cross-lagged paths from either trauma to avoidance coping (χ2= 2.83(2), p = .24) or avoidance coping to trauma (χ2=1.30(3), p = .73), suggesting no evidence for prospective within-person associations. Gender was significantly related to the intercept of trauma (B= −.18, p <.001), such that females had significantly higher levels of trauma during freshman year. Baseline PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with high initial levels of trauma (B= .01, p = .003), high initial levels of avoidance coping (B= .01, p <.001), and quick decreases in avoidance coping over the course of college (B= −.002, p <.001). Pre-college trauma was associated with high levels of trauma during freshman year (B= .12, p <.001), quick decreases in trauma over the course of college (B= −.08, p <.001), and higher initial levels of avoidance coping (B= .02, p = .007).

Summary for Bivariate Models.

The slope of trauma was positively associated with the slopes of both social support-seeking and avoidance coping. These findings suggest that slower than average declines in trauma are associated with slow decreases in avoidance coping and increases in social support-seeking over the course of college. Importantly, there was also support for within-person effects. When approach coping and social-support seeking were higher than expected given an individual’s growth trajectory, levels of trauma decreased one year later, though the effect for social support-seeking fell just short of conventional criteria for statistical significance. We also observed a marginally significant within-person effect of trauma exposure on approach coping, such that trauma was associated with increases in approach coping subsequent time point. We did not find within-person associations for avoidance coping.

Discussion

Trauma can have devastating effects on mental health and functioning (Dulin & Passmore, 2010; Hovens et al., 2010; Ball & Links, 2009). Coping is an important transdiagnostic factor implicated in mental health and may be a critical focal point for prevention and treatment of psychological distress. Research suggests an association between trauma exposure and coping style, yet the ways in which trauma and coping influence one another across time have not been well-examined. With the present study, we offer what is to our knowledge the first prospective test of theorized associations between traumatic events and coping styles. Our study had several strengths. First, our analytic approach allowed us to disaggregate within-person and between-person effects to explore individual level changes that characterize how trauma and coping may influence one another. Further, we were able to follow our large sample of young adults across four time points and spanning four years, allowing for strong tests of the directionality of the proposed associations. Finally, in addition to an approach and avoidance style, our inductive approach to classifying coping revealed a social support-seeking style, which has been much less studied and is a novel contribution to the extant literature. This style may be particularly relevant for those with trauma exposure given that having social support is an important factor in predicting positive adaptation following trauma (e.g. Brewin et al., 2000).

Taken together, findings from baseline associations suggest that individuals with a history of trauma show a distinct pattern of coping that differs from those without such a history. At baseline, pre-college trauma exposure predicted higher avoidance coping, higher social support-seeking, and lower approach coping. This finding is consistent with the cross-sectional work on approach and avoidance coping (Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Leitenberg, Gibson, & Novy, 2004; Ullman et al., 2013; Vaughn-Coaxum et al, 2018) and lends support to the idea that those with trauma histories tend to have poorer coping abilities compared to their peers. Findings pertaining to social support-seeking suggest that those with trauma histories tend to rely on others to cope with stress. This is consistent with at least some prior work showing increased efforts to seek out social connection by those with trauma (Shira, Read, Young, Bachrach, & Troisi, 2017). Findings from our longitudinal analyses yielded several interesting patterns of association, which are detailed next. Interestingly, our within-person associations revealed a different pattern of findings compared to the between-level baseline associations described above.

Coping Influences on Trauma Exposure.

At the within-person level, we found support for Stress Generation Theory (Hammen, 1985). Our results indicated an effect for approach coping and a marginal effect for social support-seeking, such that when an individual’s approach or social support-seeking was higher than expected given growth, this predicted a decrease in subsequent trauma exposure. These findings point to the potentially protective role of these coping styles in preventing new trauma and may help explain why individuals appear to have different risks for experiencing trauma (see review by O’Donnell et al., 2017). The mechanism behind this finding is not clear, but we offer some speculation. For one, individuals higher in approach coping and social support-seeking may be more proactive in anticipating, mitigating, and perhaps even preventing trauma. It is also possible that coping impacts trauma exposure indirectly; individuals who are more proactive in addressing problems may be more likely to garner resources (e.g. financial, educational, social; Moos, Brennan, Fondacaro, & Moos, 1990) which may help prevent certain traumas. Further, these individuals may select into less risky contexts (e.g. healthier relationships) and may be less likely to engage in risky behaviors (e.g. substance use), which may also protect against trauma exposure. More work is needed to examine these hypotheses.

Trauma Influences Exposure on Coping.

As noted, some work suggests that coping may change in response to life experiences (e.g., Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Leitenberg et al., 2004; Marusak et al., 2015; Ullman et al., 2013; Vaughn-Coaxum et al, 2018). Based on the cross-sectional research on childhood trauma and poor coping, we hypothesized that trauma exposure would have a detrimental effect of coping ability (i.e. increase in avoidance coping, decrease in approach coping). Yet, in our within-person examination, we did not find evidence for such a deleterious effect. Instead, we observed a trend that suggested positive adaptation in the aftermath of trauma. That is, increases in trauma exposure marginally predicted higher use of approach coping at the subsequent year. This finding is consistent with the one other longitudinal study that has been conducted, by Najdowski and Ullman (2011), which found an increase in adaptive coping styles following sexual assault. When considered with the Najdowski and Ullman (2011) findings, our data suggest that in response to trauma, individuals may learn and adopt new and adaptive coping strategies in order to meet the psychological and emotional demands of trauma exposure. This is consistent with a growing literature on the phenomenon of posttraumatic growth. Posttraumatic growth is characterized by personal growth following trauma, including an increased appreciation of life, increased personal strength, or a positive spiritual change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). In summary, rather than observing vicious cycle in which individuals become more vulnerable to trauma over time, our findings suggest that those in our sample were less at-risk for trauma over the four years and developed more adaptive ways of coping.

Interestingly, we did not observe any within-person effects for avoidance coping. This is in striking contrast to findings from most of the cross-sectional work on trauma and coping (i.e. Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Leitenberg, Gibson, & Novy, 2004; Ullman et al., 2013; Vaughn-Coaxum et al, 2018) and from the Najdowki and Ullman (2011) longitudinal study, much of which has shown positive associations between trauma and avoidance strategies. It may be that this form of coping is more trait-like, and less malleable in response to trauma relative to other forms of coping during emerging adulthood. We offer this interpretation cautiously, as this finding warrants further inquiry.

Clinical Implications

Our findings have important clinical implications. Interventions targeted towards populations most at-risk for trauma (e.g., those with victimization histories, homeless youth) may consider incorporating coping skills training in which individuals could be taught to proactively address stressors and seek out others for help. This may be more important than trying to decrease avoidance strategies, which did not have an impact on future trauma in our sample. Furthermore, in addition to treating post-trauma symptoms, clinicians working with trauma-exposed populations may also work towards fostering and encouraging ways in which clients may be able to grow or develop (e.g., posttraumatic growth; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) in the wake of a trauma, given that we observed an increase in approach coping after trauma. This is consistent with emerging positive psychology perspectives, focusing on fostering growth and resilience, and not simply on ameliorating hazardous outcomes. Finally, our findings may help prevention efforts in identifying those most at risk for experiencing future trauma (i.e., low approach coping and social support-seeking).

Limitations and future directions

There are limitations to this study that should be considered in the interpretation of our findings. First, in this study, coping was assessed yearly, which precludes examination of finer-grained changes that may occur in the immediate aftermath of trauma. In the weeks following a trauma, many individuals experience acute stress symptoms that they must adequately cope with, such as anxiety, fear, helplessness, and increased hyperarousal symptoms (see Vance, Kovachy, Dong, & Bui, 2018). Importantly, the way in which individuals cope with acute, post-trauma distress has been shown to predict the development of PTSD, among other psychological disorders (Holeva, Tarrier, & Wells, 2001). Future studies should examine how trauma impacts coping in the short-term, and to examine whether these changes impact longer-term post-trauma adaptation. The fact that we assessed coping at one-year intervals may account for why we did not see any change in avoidance coping with trauma exposure in the timeframe we studied. Still, increases in avoidance coping in the aftermath of trauma may acutely influence post-trauma adaptation, even if these changes in coping are not sustained in the long-term. These short-term processes may still be of clinical significance, and thus, more work in this area is warranted. Further, given the relatively low base rates for the traumas in our sample, we did not have statistical power to examine these associations for individual trauma types (e.g., the impact of car accidents, sexual assault, etc.). This may be an important future direction. Further, our sample consisted of college students. Young adulthood is an important developmental time period (Arnett, 2000) during which trauma is common (Marx & Sloan, 2002; Read, Ouimette, White, Colder, & Farrow, 2011; Scarpa et al., 2002). Moreover, the college setting is a context associated with high rates of trauma exposure, particularly sexual trauma (Read et al., 2011; Ullman & Filipas, 2005). As such, our examination of trauma and coping during this important developmental period lays new groundwork in understanding these processes. Nonetheless, college students may differ from other samples in ways important to trauma responding. As such, our findings are generalizable only to college students. It will be important to examine these associations in other age groups, developmental periods, and contexts in order to increase generalizability of these findings and to capture period when coping might be most malleable. Next, it should be noted that many of the effect sizes for change in our variables were small, which is consistent with our prior work in this sample (Jenzer et al., 2018). This may also explain why some of our findings were marginally significant. It would be important to compare our effect sizes with those in other samples. Finally, our measure of PTSD symptoms (which was a control variable) utilized the DSM-IV version of the PCL because data collection started prior to publication of the DSM-V, and may therefore not fully reflect the current operationalization of the construct in the newer DSM-5 version.

Clinical Impact Statement:

This study highlights the role of coping in being protective against trauma exposure, particularly social support-seeking and approach coping. Findings suggest that coping is a key process to target in vulnerable populations to improve trauma prevention efforts. There was also evidence for increased approach coping in the aftermath of trauma, potentially suggestive of posttraumatic growth in college students.

Narrative description of other published works.

Most of the published studies with this dataset have focused on variable 1 and its relationship to variable 2 and 3. None of these studies have looked at the effects of variable 4, which is one of the primary aims of the current manuscript. Further, only two other studies have used variable 5. MS 1 (published) examined how variable 3 and variable 6 predicted variable 5 across college. MS 2 (published) examined the bidirectional associations among variable 2, variable 5, and variable 1. The current article does not focus on variables 1, 2, or 3 and thus differs significantly from other manuscripts using this dataset. Furthermore, the primary aims of this paper have never been examined in previous publications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA018993) to Dr. Jennifer P. Read. We would like to thank Craig Colder, Jacquelyn White, Paige Ouimette, Jennifer Merrill, Jeffrey Wardell, the members of the ARL for their assistance with data collection and preparation of study materials, as well as the participants who made this study possible.

References

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American psychologist, 55(5), 469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball JS, & Links PS (2009). Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: evidence for a causal relationship. Current psychiatry reports, 11, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF (2003). Ego depletion and self-regulation failure: A resource model of self-control. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(2), 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro M, Novović Z, & Gavrilov V (1997). Coping strategies in PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(4), 365–369. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, & Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour research and therapy, 34(8), 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, & Davis GC (1999). Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. American journal of Psychiatry, 156, 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, & Schultz LR (2000). A second look at comorbidity in victims of trauma: The posttraumatic stress disorder–major depression connection. Biological psychiatry, 48, 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, & Valentine JD (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 748–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. International journal of behavioral medicine, 4(1), 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Hammen C, & Brennan PA (2012). Expanding stress generation theory: Test of a transdiagnostic model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 754–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conybeare D, Behar E, Solomon A, Newman MG, & Borkovec TD (2012). The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version: Reliability, validity, and factor structure in a nonclinical sample. Journal of clinical psychology, 68, 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Burgess P, & McFarlane AC (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychological medicine, 31, 1237–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Howard AL, Bainter SA, Lane ST, & McGinley JS (2014). The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: A latent curve model with structured residuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual review of psychology, 62, 583–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, Bush KR, McFall M, Epler AJ, & Bradley KA (2002). Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in female Veteran’s Affairs patients: validation of the PTSD checklist. General Hospital Psychiatry, 24(6), 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin PL, & Passmore T (2010). Avoidance of potentially traumatic stimuli mediates the relationship between accumulated lifetime trauma and late-life depression and anxiety. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 23, 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipas HH, & Ullman SE (2006). Child sexual abuse, coping responses, self-blame, posttraumatic stress disorder, and adult sexual revictimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(5), 652–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Read JP, Young AF, Bachrach RL, & Troisi JD (2017). Social surrogate use in those exposed to trauma: I get by with a little help from my (fictional) friends. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 36(1), 41–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavranidou M, & Rosner R (2003). The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depression and anxiety, 17(3), 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, Van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, & Zitman FG (2010). Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(1), 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Marks T, Mayol A, & DeMayo R (1985). Depressive self-schemas, life stress, and vulnerability to depression. Journal of abnormal psychology, 94(3), 308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EM (2016). Quality of life and mental health among women with ovarian cancer: examining the role of emotional and instrumental social support seeking. Psychology, health & medicine, 21(5), 551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, & Schutte KK (2005). Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 73(4), 658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeva V, Tarrier N, & Wells A (2001). Prevalence and predictors of acute stress disorder and PTSD following road traffic accidents: Thought control strategies and social support. Behavior Therapy, 32(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jenzer T, Read JP, Naragon-Gainey K, & Prince MA (2018). Coping trajectories in emerging adulthood: The influence of temperament and gender. Journal of personality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of traumatic stress, 26, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed). New York, NY: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, & Burns K (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological assessment, 12(2), 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Coping and adaptation. The handbook of behavioral medicine, 282–325. [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Gibson LE, & Novy PL (2004). Individual differences among undergraduate women in methods of coping with stressful events: The impact of cumulative childhood stressors and abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(2), 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, & Alloy LB (2010). Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical psychology review, 30(5), 582–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusak HA, Martin KR, Etkin A, & Thomason ME (2015). Childhood trauma exposure disrupts the automatic regulation of emotional processing. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(5), 1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, & Sloan DM (2002). The role of emotion in the psychological functioning of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Behavior Therapy, 33(4), 563–577. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & Lambert HK (2017). Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: mechanisms of risk and resilience. Current opinion in psychology, 14, 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Zimering R, Daly E, Knight J, Kamholz BW, & Bird GS (2012). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological symptoms in trauma-exposed firefighters. Psychological Services, 9, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Brennan PL, Fondacaro MR, & Moos BS (1990). Approach and avoidance coping responses among older problem and nonproblem drinkers. Psychology and Aging, 5, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, & Holahan CJ (2003). Dispositional and contextual perspectives on coping: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of clinical psychology, 59(12), 1387–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, & Ullman SE (2011). The effects of revictimization on coping and depression in female sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(2), 218–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, & Pattison P (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma: understanding comorbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1390–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell ML, Schaefer I, Varker T, Kartel D, Forbes D, Bryant RA, … & Felmingham K (2017). A systematic review of person-centered approaches to investigating patterns of trauma exposure. Clinical psychology review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Johnson DC, & Southwick SM (2010). Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation in veterans of operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Journal of Affective Disorders, 123, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Haden SC, & Hurley J (2006). Community violence victimization and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(4), 446–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell DL, Siegert RJ, Hay-Smith EJC, & Surgenor LJ (2011). Factor structure of the Brief COPE in people with mild traumatic brain injury. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 26(6), 468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, & Helgeson VS (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and social psychology review, 6(1), 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, & Stanton AL (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol, 3, 377–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, & Calhoun LG (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of traumatic stress, 9(3), 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of health and social behavior, 52, 145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Ouimette P, White J, Colder C, & Farrow S (2011). Rates of DSM–IV–TR trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among newly matriculated college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(2), 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, & Filipas HH (2005). Ethnicity and child sexual abuse experiences of female college students. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 14(3), 67–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance MC, Kovachy B, Dong M, & Bui E (2018). Peritraumatic distress: A review and synthesis of 15 years of research. Journal of clinical psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn-Coaxum RA, Wang Y, Kiely J, Weisz JR, & Dunn EC (2018). Associations between trauma type, timing, and accumulation on current coping behaviors in adolescents: results from a large, population-based sample. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(4), 842–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]