Abstract

At least 200 million girls and women across the world have experienced female genital cutting (FGC). International migration has grown substantially in recent decades, leading to a need for health care providers in regions of the world that do not practice FGC to become knowledgeable and skilled in their care of women who have undergone the procedure. There are four commonly recognized types of FGC (Types I, II, III, and IV). To adhere to recommendations advanced by the World Health Organization (WHO) and numerous professional organizations, providers should discuss and offer deinfibulation to female patients who have undergone infibulation (Type III FGC), particularly before intercourse and childbirth. Infibulation involves narrowing the vaginal orifice through cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or labia majora, and creating a covering seal over the vagina with appositioned tissue. The World Health Organization has published a handbook for health care providers that includes guidance in counseling patients about deinfibulation and performing the procedure. Providers may benefit from additional guidance in how to discuss FGC and deinfibulation in a manner that is sensitive to each patient’s culture, community, and values. Little research is available to describe decision-making about deinfibulation among women. This article introduces a theoretically-informed conceptual model to guide future research and clinical conversations about FGC and deinfibulation with women who have undergone FGC, as well as their partners and families. This conceptual model, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, may facilitate conversations that lead to shared decision-making between providers and patients.

Keywords: Theory of Planned Behavior, Female Genital Cutting, Female Genital Mutilation, Female Circumcision, Infibulation, Deinfibulation, Reinfibulation, Shared Decision-Making

At least 200 million girls and women across the world have experienced female genital cutting (FGC) (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016). While FGC is practiced primarily in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, and to a lesser extent in Asia and the Middle East (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016), international migration has grown substantially in recent decades (United Nations, 2015). For this reason, FGC is becoming a localized concern in regions of the world that do not practice FGC (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). Health care providers who treat migrant and immigrant populations are increasingly being called upon to demonstrate knowledge and skill in their care of women who have undergone FGC (WHO, 2018). To adhere to recommendations advanced by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) and numerous professional organizations (American College of Nurse-Midwives [ACNM], 2017; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007; Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists [RCOG], 2015; Perron, Senikas, Burnett, & Davis, on behalf of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada [SOGC], 2013), providers should discuss and offer deinfibulation to female patients who have undergone infibulation, a specific type of FGC, particularly before intercourse and during pregnancy, in preparation for childbirth.

Providers are often unprepared to discuss FGC and deinfibulation in a manner that is sensitive to each patient’s culture, community, and values (Hamid, Grace, & Warren, In Press; Johnson-Agbakwu, Helm, Killawi, & Padela, 2014). Without a model for addressing FGC and deinfibulation in a culturally sensitive manner, providers risk offending and alienating their patients, which in turn may reduce the likelihood that girls and women choose deinfibulation, despite its potential for alleviating chronic health conditions that are caused by FGC. The World Health Organization (2016) has noted that research is urgently needed to understand factors that facilitate or act as barriers to deinfibulation. The purpose of the present article is to introduce a theoretically-informed conceptual model to guide future research and clinical conversations about FGC and deinfibulation with women who have undergone FGC, as well as their partners and families. This conceptual model may facilitate conversations that lead to shared decision-making between providers and patients (Dugas et al., 2012; Légaré, Ratté, Gravel, & Graham, 2008).

Female Genital Cutting (FGC)

Terminology

Female genital cutting (FGC), also known as female genital mutilation or FGM, refers to any procedure involving the partial or total removal of external genitalia (WHO, 2016). Female genital mutilation was adopted as a term by the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices, and World Health Organization in the 1990s to frame FGC as a form of violence against women and a violation of women’s rights to bodily integrity and health (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). The term “female genital mutilation” drew a sharp distinction between feminist and human rights perspectives of FGC, which were becoming more dominant, and perspectives that had prevailed within academic and professional circles in the past. These perspectives had framed FGC as a social and cultural tradition subject to sovereign autonomy (e.g., a rite of passage on a par with circumcision of boys) (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). Indeed, communities that adhere to FGC may refer to the practice as “female circumcision” (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). Arguably, the term “female genital mutilation” has been instrumental in generating political will to curb the practice of FGC and work towards eradicating FGC. However, many communities who have adhered to the practice of FGC in the past or present find the word “mutilation” to be judgmental, demeaning, offensive, and alienating (ACOG, 2007; United Nations Population Fund, 2018; von Rege & Campion, 2017). To be respectful of the community whose medical decision-making is the focus of this article, the term FGC is used henceforth. “Cutting” accurately describes different FGC procedures that are described below, whereas “circumcision” is a misleading term given the extent of female anatomy that may be altered by FGC and harmful effects of FGC on girls’ and women’s health (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). However, providers should be willing to use any terminology that is viewed positively by patients and their families, including “circumcision,” “excision,” and other terminology that is specific to patients’ culture and language (National FGM Centre, 2017).

FGC Types

There are four commonly recognized types of FGC: Types I, II, III, and IV (WHO, 2008; WHO, 2016). Only Type III FGC involves infibulation, the focus of this article. Type III FGC, infibulation, is defined as the “narrowing of the vaginal orifice with the creation of a covering seal” over the vagina. Infibulation is achieved “by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris” (WHO, 2008; WHO, 2016). Infibulation may occur as a result of the practitioner’s stitching the appositioned genitalia together or as a result of natural healing after tissue of the labia minora or majora has been cut (WHO, 2016). The remaining types of FGC do not involve infibulation. Type I FGC involves “partial or total removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy) and/or the prepuce.” Type II FGC involves “partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)” (WHO, 2008; WHO, 2016). Type IV FGC involves “all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization” (WHO, 2016).

Health Complications of FGC

Immediate physical health complications of FGC include hemorrhage, pain, shock, swelling of genital tissue, problems with urination, infections of the genital, reproductive, and urinary tracts, problems with wound healing, and death (Berg, Underland, Odgaard-Jensen, Fretheim, & Vist, 2014; Ivazzo, Sardi, & Gkegkes, 2013). Long-term physical health complications include infections of the genital, reproductive, and urinary tracts, vaginal itching and discharge, problems with menstruation, painful urination, and chronic vulvar and clitoral pain (Berg et al., 2014; Ivazzo et al., 2013). Negative effects of FGC on mental health and psychological well-being (e.g., anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder; Vloeberghs, van der Kwaak, Knipsheer, & van den Muijsenbergh, 2012) have also been observed. FGC may negatively impact relationships with caregivers who permitted FGC to occur (Parikh, Saruchera, & Liao, In Press). Relationships with partners may also be impacted, as FGC may reduce sexual desire, arousal, and lubrication; frequency of orgasm; and sexual satisfaction (Berg et al., 2014; Berg, Denison, & Fretheim, 2010). Infibulation (Type III FGC) is particularly likely to be associated with pain during sexual intercourse and complications of labor and childbirth (WHO, 2006; Berg, Odgaard-Jensen, Fretheim, Underland, & Vist, 2014; Connor et al., 2016). Both neurobiological and sociocultural mechanisms may influence perceptions of pain among women who have undergone infibulation (Einstein, 2008; Johansen, 2002).

Historical Origins and Cultural Perspectives of FGC

FGC is described by leaders from the United Nations and World Health Organization as a “manifestation of gender inequality that is deeply entrenched in social, economic, and political structures” (WHO, 2008). The practice of FGC is thought to pre-date both Christianity and Islam (WHO, 2008) and is not mentioned in the Bible or Quran (WHO, 2016). Justifications by practitioners have included the preservation of virginity, prevention of rape, restraint of women’s sexual desire, assurance of women’s fidelity after marriage, and belief that men will only marry women who have undergone the procedure (Graamans, Ofware, Nguura, Smet, & ten Have, 2018; WHO, 2008; WHO, 2016). Infibulation, Type III FGC, may have been practiced on female slaves in Ancient Rome to prevent pregnancy, which would have “rendered slaves unfit for work” (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). Centuries of practice in different societies across socioeconomic strata may have led to widespread beliefs that FGC is necessary to make a girl or woman’s body “clean,” beautiful, and more feminine (Graamans et al., 2018; WHO, 2008; WHO, 2016) and that the pain constitutes a rite of passage (Graamans et al., 2018). Even when adults recognize that FGC inflicts harm against girls and women, they may fear that departing from the norm of FGC will lead to condemnation and stigmatization by one’s elders, peers, and community (WHO, 2008). For those who view FGC as essential to the identity of girls and women, efforts to combat the practice may be viewed as an attack on their community’s identity and culture (WHO, 2008). International campaigns to ban FGC have been perceived by some as racialist, post-colonial, and “a crusade by feminists from the North”; these campaigns may inadvertently overshadow community initiatives to curb FGC (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016).

Current Prevalence of FGC

Today, the prevalence of FGC varies greatly across countries. It is most concentrated in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, and to a lesser extent in Asia – particularly Indonesia – and parts of the Middle East (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016). Among countries for which data is available, prevalence rates range from 0.2% (Benin) to 56% (Gambia) among girls aged 0–14 years, and from 1% (Cameroon and Uganda) to 98% (Somalia) among girls and women aged 15–49 years (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016). Infibulation, Type III FGC, is localized in eastern Africa, with 77% of women in Somalia, 62% in Djibouti, and 35% in Eritrea estimated to have undergone the procedure (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). In other regions, infibulation represents less than 10% of FGC cases (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). In countries of immigration, direct estimates of FGC are not available due to the lack of nationally representative surveys with modules on FGC (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). The “extrapolation method” of obtaining indirect estimates involves identifying age-specific prevalence rates from surveys administered in countries of origin, and then using migration statistics to estimate the number of women in countries of immigration who have experienced FGC (Macfarlane & Dorkenoo, 2015). Characteristics of women who immigrate are not necessarily representative of women who are surveyed in countries of origin, however. One study of women presenting for maternity care in the Lothian region of Scotland suggests that the extrapolation method can overestimate the true prevalence of FGC (Ford, Darlow, Massie, & Gorman, 2018).

There has been an overall decline in the worldwide prevalence of FGC during the past three decades. However, not all countries have made progress and the pace of decline has been uneven (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016). Local structures of power and authority, including elder women, religious leaders, and some medical personnel, may uphold the practice of FGC (WHO, 2008). International migration has grown substantially in recent decades (United Nations, 2015), which exposes families to the beliefs and practices of different cultures. While it is anticipated that immigrant communities will be influenced by norms of the countries in which they have settled, and that community members will be less likely to adhere to FGC over time, this progression is not guaranteed. Some scholars have hypothesized that experiences of discrimination and disadvantage in one’s new home could lead to the continued practice of FGC as a means of affirming one’s identity (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). Thus, a variety of factors may serve to reinforce the practice of FGC, both in regions of the world that do and do not support a cultural norm of FGC.

Deinfibulation

Current Recommendations for Deinfibulation

Deinfibulation refers to the practice of cutting open the narrowed vaginal opening in a woman who has been infibulated (Type III FGC); this is often necessary to enable vaginal intercourse or childbirth (Abdulcadir, Marras, Catania, Abdulcadir, & Petignat, In Press; WHO, 2016). The World Health Organization (2016, 2018) recommends deinfibulation in girls and women living with Type III FGC to prevent and treat gynecologic and urologic complications – particularly menstrual disorders such as hematocolpos (menstrual blood that has accumulated in and cannot easily pass through the vagina) or other causes of dysmenorrhea (painful periods), recurrent urinary tract infections, and urinary retention – as well as to facilitate childbirth and prevent and treat obstetric complications. For these reasons, several professional organizations, including the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (2015), Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (Perron et al., on behalf of SOGC, 2013), American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2007) and American College of Nurse-Midwives (2017), also recommend deinfibulation. Deinfibulation may confer benefits to sexual health as well as physical health. Berg and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the literature and found that deinfibulation reduces pain during intercourse and improves sexual functioning (e.g., desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction) (Berg, Taraldsen, Said, Sorbye, & Vangen, 2018).

Barriers to Deinfibulation

Despite the fact that deinfibulation – the surgical separation of fused labia – is a recommended procedure (WHO, 2016), both provider and patient factors can limit its implementation. Many health care providers lack knowledge about deinfibulation and avoid offering it (Smith & Stein, 2017). Some providers fear that discussing the procedure will be perceived as intrusive or culturally insensitive by women who have undergone infibulation (Smith & Stein, 2017). Even if a health care provider is comfortable discussing and offering deinfibulation, several factors may result in patient reluctance to be deinfibulated. Many women who have undergone infibulation are not aware that deinfibulation is an option (Berg, Taraldsen, Said, Sorbye, & Vangen, 2017). When deinfibulation is understood, women may fear that their husband, a future husband, female elders, and community will not accept the procedure (Berg et al., 2017; Johnson-Agbakwu, Helm, Killawi, & Padela, 2014), particularly if deinfibulation is provided before marriage or childbirth. Cultural associations between the practice of FGC and women’s virginity and virtue are a major barrier to the adoption of premarital deinfibulation (Johansen, 2017a). In some cultures, men and women believe that penile deinfibulation (i.e., penetrating the infibulated vagina with the husband’s penis) is a means of proving men’s virility and masculinity; it could bring shame to a couple if one’s community learned that deinfibulation was achieved through a medical procedure (Johansen, 2017b). Even after pregnancy and childbirth, both women and men may wish to retain a small vaginal opening because they consider it to be a prerequisite for male sexual pleasure (Johansen, 2017b). While most women readily understand that deinfibulation will facilitate an easier childbirth, many prefer to have the procedure performed during labor rather than antenatally (Berg et al., 2017). They may also wish to heal naturally or be reinfibulated after childbirth in order to return to having a small vaginal opening (Rushwan, 2000), rather than being “sewn open” to prevent tissue from resealing. Deinfibulation may cause distress in women who perceive that their new genitalia are unattractive (Berg et al., 2017), and this could conceivably impact whether a woman chooses to remain deinfibulated.

Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to the Decision to Deinfibulate

Behavioral scientists and clinical providers can apply theory to better understand and address patient reluctance to deinfibulate. A theory is a set of concepts, definitions, and propositions that explain or predict behaviors or situations (National Cancer Institute, 2005). Theories must be applicable to a broad variety of behaviors and situations and must be testable; results may or may not support the theory (National Cancer Institute, 2005). In contrast to a theory, a conceptual model is a diagram of proposed causal linkages among a set of concepts believed to be related to a particular behavior or situation (Earp & Ennett, 1991). Of relevance to this article, theory can be used to develop a conceptual model that guides research inquiry about proposed determinants of a woman’s decision to deinfibulate. The same conceptual model can be used to guide topics of conversation when clinical providers attempt to have culturally appropriate conversations with patients about deinfibulation.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015) is an ideal theory to apply to the design of a conceptual model explaining deinfibulation – a behavior that appears to be both individually and socially determined. The Theory of Planned Behavior focuses on three constructs – one’s attitudes towards the behavior, perceived norms with respect to the behavior, and perceived control over the behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior was developed to improve the explanatory power of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), which includes the first two constructs, attitudes and perceived norms. Both the Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action posit that the most proximal determinant of a deliberate behavior is intention to perform the behavior. Intention is determined by attitudes towards and perceived norms about the behavior. By adding the construct of perceived control as a determinant of intention, the Theory of Planned Behavior acknowledges situations where one may not have complete control over behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015).

The Theory of Planned Behavior has been used to explain and change a myriad of health behaviors (Godin & Kok, 1996), including diet (Hackman & Knowlden, 2014), physical activity (Blue, 1995), smoking (Tola & Moriano, 2010), alcohol use (Kuther, 2002), driving practices (Godin & Kok, 1996), and sexual behaviors (Tyson, Covey, & Rosenthal, 2014). The Theory of Planned Behavior has also been used to explain medical decision-making (Godin & Kok, 1996), including seeking dental care services (Vieira & Leles, 2014), mammography (Griva, Anagnostopoulos, & Madoglou, 2009), and other cancer screening (Godin & Kok, 1996). In at least two studies – one conducted in Nigeria and the other in Iran – the Theory of Planned Behavior has been used to understand parents’ intentions to allow or disallow their daughters to undergo FGC (Ilo et al., 2018; Pashaei, Ponnet, Moeeni, Khazaee-pool, Majlessi, 2016). In both studies, attitudes, perceived norms, and perceptions of control about FGC were independently associated with parents’ intentions, even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors.

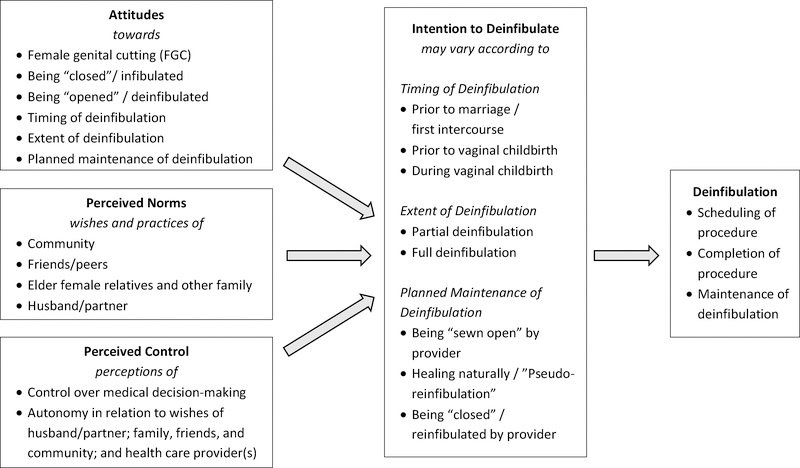

A literature search yielded no instances in which the Theory of Planned Behavior or other health behavior theories have been applied to women’s decision-making with respect to deinfibulation in research contexts (e.g., understanding decision-making, attempting to influence decisions through intervention programs) or clinical contexts (e.g., guiding providers’ conversations with patients about deinfibulation). Figure 1 depicts a conceptual model in which the Theory of Planned Behavior has been applied to a woman’s decision to deinfibulate after experiencing infibulation (Type III FGC). This model characterizes deinfibulation as an individually and socially determined behavior over which women may have varying levels of control.

Figure 1.

Theory of Planned Behavior, applied to a woman’s decision to deinfibulate after experiencing female genital cutting (FGC).

Attitudes towards Deinfibulation

Attitudes may be assessed in relation to the practice of FGC, the experience of being infibulated (“closed”), and the idea of being deinfibulated (“opened”). A woman’s attitudes towards deinfibulation may vary with respect to timing (i.e., prior to marriage and/or first intercourse, prior to vaginal childbirth, during vaginal childbirth), extent (i.e., partial or full deinfibulation), and planned maintenance (i.e., being “sewn open” by a health care provider to prevent tissue of the genitalia from resealing, healing naturally after childbirth, or being reinfibulated after childbirth) (Figure 1, upper left).

The first column of Table 1 includes definitions of the Theory of Planned Behavior constructs that are featured in Figure 1. The Theory of Planned Behavior defines attitudes as values attached to anticipated behavioral outcomes (e.g., perceptions of whether good or bad things will happen after being deinfibulated; Ajzen, 1991). In extensions of the Theory of Planned Behavior, this type of expectancy-value is also known as an instrumental attitude (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). Instrumental attitudes that may increase intention to deinfibulate include beliefs that deinfibulation will facilitate sexual intercourse and reduce accompanying pain, improve sexual functioning, facilitate childbirth, prevent obstetric complications, and prevent gynecological and urologic complications. Instrumental attitudes that may decrease intention to deinfibulate include beliefs that deinfibulation will make one less eligible as a marriage partner, decrease a husband’s sexual pleasure, and bring shame to oneself and one’s family. Experiential attitudes – feelings attached to a behavior – have been discussed in extensions of the Theory of Planned Behavior and may also be important to consider (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). Experiential attitudes that may increase or decrease intention to deinfibulate include feelings of delight or revulsion towards the idea of having an “open” vagina, respectively.

Table 1.

Applying Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs to qualitative research and clinical practice.

| TPB Construct and Definition a | Relevant Questions and Suggested Language to Enhance Cultural Sensitivity and Competence d |

|---|---|

|

Attitudes Instrumental Attitudes: Value attached to an anticipated behavioral outcome Experiential Attitudes: Feeling attached to a behavior b |

Preface to questions: In every community and culture, there are beliefs and practices that have been passed down from generation to generation. Sometimes these beliefs and practices fit with our own way of thinking, and other times they do not. It is also possible to have conflicting or mixed thoughts about the practices of our community and culture – to think of things as both good and bad. I’d like to ask what you think about the practice of female genital cutting in your community and culture. I’d also like to ask what you think about having your genitalia be “closed,” which medical providers call being “infibulated,” and what you think about the idea of having your genitalia be opened, which medical providers call being “deinfibulated.” Would it be acceptable to you if we have this conversation together? • What good things may happen for a girl or woman whose genitalia are “closed”? What bad things may happen for a girl or woman whose genitalia are “closed”? What good and bad things have happened for you since you were “closed”? • What good things may happen for a girl or woman whose genitalia are “opened”? What bad things may happen for a girl or woman whose genitalia are “opened”? What good and bad things do you think would happen for you if you decided to have your genitalia be “opened”? • How do you feel about... – the practice of female genital cutting in your community and culture? – living with your genitalia being “closed,” or in other words, infibulated? – the idea of being “opened” one day, or in other words, deinfibulated? |

| • Do your feelings about being “opened,” or in other words, deinfibulated, depend on... – The timing of deinfibulation, such as whether it occurs prior to marriage and first intercourse, prior to vaginal childbirth, or during vaginal childbirth? – The extent of deinfibulation, such as whether you are only partially “opened” or “opened” all the way? – Your plans for whether you will stay “opened”? For example, some women are “sewn open” by their health care provider so that they will stay open after being cut open. Some women are “opened” prior to childbirth and heal naturally afterwards so that the tissue of the genitalia will close again. And some women ask their health care provider to “sew them closed” after childbirth. (Be prepared to address whether this is allowable.) |

|

| Preface to additional questions: Often times, we are members of different communities. For example, there is the community and culture of the country where your family has moved from. There is the community and culture of other (ethnic group or nationality) people where you live now. There is also the broader community and culture, which includes everybody here in our (town/city), state, and (country of residence). | |

| • To what communities do you feel a sense of belonging? • Would your answers to the questions we have been talking about be any different if you thought of the different communities to which you belong? (If so), – Do your feelings about living with your genitalia being “closed” differ when you think about the different communities to which you belong? – Do your feelings about the idea of being “opened” differ when you think about the different communities to which you belong? |

|

|

Perceived Norms Subjective/ Injunctive Norms: Whether others approve of the behavior Descriptive Norms: Whether others have engaged in the behavior b |

Preface to questions: We all can think of other people who we look to for guidance on important issues, such as how we take care of our bodies. These people might include our elder female relatives, such as a mother, mother- in-law, auntie, or grandmother; our wider family and community; our friends; and (if applicable) our husband or partner. • When it comes to how you take care of your body, whose opinions and advice is very important to you? • If you were to talk about the idea of being “opened,” or in other words, deinfibulated, who would support your doing this? Who would be against your doing this? (If not mentioned, probe about the wishes of the woman’s husband/partner, elder female relatives and other family members, friends/peers, and different communities to which the woman belongs.) • Would the opinions and advice of these valued people depend on... – The timing of deinfibulation, such as whether it occurs prior to marriage and first intercourse, prior to vaginal childbirth, or during vaginal childbirth? – The extent of deinfibulation, such as whether you are only partially “opened” or “opened” all the way? – Your plans for whether you will stay “opened”? For example, some women are “sewn open” by their health care provider so that they will stay open after being cut open. Some women are “opened” prior to childbirth and heal naturally afterwards so that the tissue of the genitalia will close again. And some women ask their health care provider to “sew them closed” after childbirth. (Be prepared to address whether this is allowable.) |

| • Of the women whose opinions and advice is very important to you, how many do you think have been “closed” at any point in their life, or in other words, infibulated? (Try to get a sense of the general percentage or proportion.) | |

| • Of the women whose opinions and advice is very important to you, and who have been “closed” in the past, how many do think have been “opened” at any point in their life, or in other words, deinfibulated? After being “opened,” how many do you think have stayed “opened?” (Try to get a sense of the general percentages or proportions.) | |

|

Perceived Control

c Extent to which external conditions facilitate or constrain behavior |

Preface to questions: In many places, such as (country of residence), women have a lot of control over decisions that are made about their medical care. In other places, women have little control. Even if women do have a lot of control over decisions about their medical care, they may wish to share this decision-making with others. This may be the case because they value other people’s opinions and advice, or because they worry about going against the wishes of people who are important to them, such as family members. • When it comes to making decisions about your medical care, to what extent do you think that you have control? To what extent do you share decision-making about your medical care with others? • (If women share decision-making to any degree) To what extent do you share decision-making with others because you value other people’s opinions and advice? To what extent do you share decision-making with others because you worry about going against the wishes of important others? Who do you share your medical decision-making with? (For each person) For what reasons do you share medical decision-making with this person? Who would have the “final say” about a medical decision? (If women do not list health care provider(s) as people with whom they share medical decision-making, probe about these individuals.) |

| • If you were leaning towards being “opened,” or in other words, deinfibulated, what would make this decision easy to do? What would make this decision hard to do? | |

| • If you were leaning towards staying “opened,” what would make this decision easy to do? What would make this decision hard to do? | |

| Intention to Deinfibulate | • Do you intend to be “opened,” or in other words, deinfibulated, over the next (time period)? – (If yes) What timing are you thinking of? (If not mentioned, probe about prior to marriage and first intercourse, prior to vaginal childbirth, and during childbirth) – (If yes) To what extent do you plan to be deinfibulated – partially, or all the way? – (If yes) What are your plans for whether you will stay “opened”? (If not mentioned, probe about being “sewn open” so that the genitalia will stay open after being cut open, being “opened” prior to childbirth and healing naturally afterwards, and – if allowable by one’s practice – being “sewn closed” to a certain extent after childbirth.) – (If no) Are there any conditions under which you could imagine being “opened” in the future? |

| • Concluding statements: Thank you for answering all of these questions. They have enhanced my understanding of you, your community, and (if the interviewer is of a different culture) your culture. Are there any questions that I can answer for you? |

Definitions are taken from Montaño and Kasprzyk (2015).

This definition of the construct was developed subsequent to the TPB and is included in an extension of the TPB, the Integrated Behavioral Model (IBM) (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). The IBM distinguishes between instrumental and experiential attitudes, and between subjective/injunctive and descriptive norms.

Questions designed to assess the extent to which women share decision-making with important referents are integrated within the perceived control section. Shared decision-making is a construct that is distinct from perceived control. In the context of health care, shared decision-making with providers may serve to reinforce or enhance patients’ perceived control and autonomy over their medical decision-making (Dugas et al., 2012; Légaré et al., 2008).

Questions could be asked during elicitation interviews (qualitative research) or culturally appropriate conversations (practice). Questions to assess each Theory of Planned Behavior construct are adapted from Montaño and Kasprzyk (2015).

Perceived Norms of Deinfibulation

Perceived norms of deinfibulation may be assessed with respect to the wishes and practices of important referents, including one’s community, friends and peers, elder female relatives and other family members, one’s husband or partner, and—for girls and women who are not yet engaged or married—one’s imagined future husband or partner (Figure 1, middle left). The Theory of Planned Behavior focuses on whether important referents approve of the behavior, which has been referred to as subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991) or injunctive norms (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015; Table 1, first column). Descriptive norms – whether important referents engage in the behavior – have been discussed in extensions of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015).

Based on the literature reviewed above, it is likely that many individuals in a woman’s social network will approve of and practice FGC. It is also likely that many social network members will disapprove of deinfibulation outside of necessary contexts (e.g., impending vaginal childbirth). Community-based social norms campaigns against FGC may change a woman’s perceptions of how others in her social network feel about FGC (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016). For example, women may perceive that others disapprove of and are abandoning the practice of FGC, and that others approve of deinfibulation in a wider variety of contexts (e.g., to prevent or alleviate adverse health consequences of FGC). Similar to a woman’s individual attitudes, the wishes and practices of important referents may vary according to the timing, extent, and planned maintenance of deinfibulation.

Perceived Control over Deinfibulation

A woman’s perceptions of her personal control over medical decision-making should be examined, particularly with respect to deinfibulation (Figure 1, lower left). A woman’s perceived control may be a function of her perceived autonomy in relation to the wishes of her husband or partner; family, friends, and community; and health care provider(s). Based on the literature reviewed above, women’s perceived control over deinfibulation may be particularly low prior to marriage, first intercourse, and childbirth. Even if a woman has favorable attitudes toward deinfibulation at these times, she may be likely to perceive that her partner, husband, or other family members will not “let” her undergo deinfibulation or that the procedure would incur displeasure from others.

In the Theory of Planned Behavior, the construct of perceived control reflects a value for individual autonomy held by many communities and societies. Patient autonomy, also known as self-determination, is at the core of medical decision-making in the United States and other countries (Fan, 1997; Ho, 2008; USLegal, n.d.). Patients are seen to have the right to make their own decisions about medical care, as long as those decisions are within the boundaries of law (USLegal, n.d.). Although women may understand that the laws of a specific country ensure their right to autonomy with respect to medical decision-making, they may worry about going against the wishes of important referents, which may serve to limit their perceptions of individual control.

An alternative conceptualization to self-determination is to view family involvement in medical decision-making as a key component of a women’s ability to act in an agentic manner. Ho (2008) examined the role of family members in critical areas of medical decision-making (e.g., resuscitation and other life-extending measures in the context of intensive care). She observed that an emphasis on self-determination by western systems of health care and bioethics can lead to suspicion against family members who exert influence on patients’ medical decision-making, which in turn can lead to animosity between health care providers and family members of patients. Ho (2008) noted that in certain ethnic and immigrant groups, patients prefer to defer decision-making to family members or to consider the wishes of family members extensively in their own decision-making. Ho (2008) distinguished between relational autonomy – culturally appropriate family involvement in decision-making and the patient’s consideration of family wishes – from undue pressure of family members on the patient’s medical decision-making. She argued that family involvement in medical decision-making and consideration of family members’ wishes by patients can be integral in promoting patients’ overall agency, particularly when the health care system is unfamiliar and may be a source of stress. Ho (2008) suggested that if family members refuse to consider the patient’s well-being and attempt to override the patient’s expressed preferences, their involvement in decision-making is unhelpful and inappropriate.

Intention to Deinfibulate and Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that a woman’s attitudes towards, perceived norms about, and perceived control over deinfibulation influences her intention to deinfibulate (Figure 1, center). Women who intend to be deinfibulated will be more likely to schedule and complete the procedure (Figure 1, far right). Those women who intend to maintain deinfibulation (e.g., beyond childbirth) will be more likely to do so. Figure 1 illustrates the complexity of medical decision-making with respect to deinfibulation. Attitudes, perceived norms, perceived control, and intentions may all vary according to the timing, extent, and planned maintenance of deinfibulation. In addition, thoughts that serve as facilitators or barriers to deinfibulation may coexist. These considerations underscore the importance of developing nuanced questions to assess each construct.

Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

Table 1 defines key constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior and applies each definition to questions that can be asked in research and clinical contexts. These questions were adapted from standard elicitation interviews developed by Montaño and Kasprzyk (2015) to assess constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior in relation to any health behavior. Unique features of the present application of theory derive from the fact that deinfibulation is a medical procedure that aims to alleviate the most pronounced physical effects of Type III FGC, a cultural practice. Given this cultural backdrop, it is recommended that research and clinical interviews not only assess how women think and feel about deinfibulation, but also how they think and feel about the practice of FGC and the experience of being infibulated. Also unique to the present application of theory are questions that assess whether (1) perceptions vary by the timing, extent, and planned maintenance of deinfibulation, and (2) women wish to share decision-making with others. It is anticipated that women might report shared decision-making for at least two primary reasons: valuing the opinions and advice of others and worrying about going against the wishes of important referents. Worry about going against the wishes of important referents is particularly suggestive of low levels of perceived control. It is possible for women to value the opinions and advice of others and still perceive high levels of autonomy or complete autonomy over their medical decision-making (Ho, 2008).

In addition to questions that directly “map onto” key constructs of the theory, Table 1 offers specific language that may enhance cultural sensitivity of interviewers. Prefaces to questions serve to normalize the passing of beliefs and practices from generation to generation, feelings of potential conflict about traditions that have been passed down over time, and fears about going against the wishes of important referents. The intent is to create a non-judgmental environment in which a woman can comfortably disclose her thoughts and feelings, regardless of whether they favor, disfavor, or are mixed with respect to FGC. In settings where a clinical provider’s time with a patient is limited, the provider should consider whether another member of the health care team could engage in an extended conversation with the patient to explore constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior.

Ideally, providers and their professional organizations, boards, and institutions should work to establish partnerships with local community-based organizations serving refugee and immigrant women who have undergone FGC. Community-engaged approaches to research and practice should include a review of the questions and language suggested in Table 1 to determine whether and how this material should be tailored to better fit populations served by providers and their institutions.

Planning Research to Understand Women’s Decision-Making about Deinfibulation

Semi-structured elicitation interviews and – depending on the comfort of participants – focus groups are needed to confirm the appropriateness of the Theory of Planned Behavior as an explanatory model for the decision to deinfibulate. Qualitative research among communities who practice FGC may provide insights about ways in which deinfibulation and the maintenance of deinfibulation may be tactfully promoted. While research has not yet examined attitudes, perceived norms, and perceptions of control in relation to deinfibulation, research has examined beliefs that may contribute to ending the practice of FGC. For example, Graamans and colleagues (2018) conducted research among Maasai and Samburu communities in Kenya and observed four rationales for challenging the practice of FGC: religious grounds (e.g., FGC is against the will of God); medical grounds (e.g., FGC poses a health risk); modernistic grounds (e.g., FGC is a violation of human rights); and love and intimacy (e.g., FGC impedes the ability to experience pleasure). These rationales may be used to inform questions designed to assess attitudes towards deinfibulation among women who have undergone Type III FGC. It is likely that focusing on variety of attitudes would yield more useful information for the development of intervention programs than focusing on health complications alone. Andro and Lesclingand (2016) observed that the first campaigns against FGC, which focused heavily on short-term health risks such as hemorrhage and infections, proved to be counter-productive because they contributed to the medicalization of FGC – performance of the procedure by a health care provider under hygienic conditions. Research is needed to identify the most compelling rationales in support of deinfibulation, including specific attitudes, perceived norms, and perceptions of control.

Qualitative data can inform item and scale development for quantitative measures of theory constructs as applied to deinfibulation. Cognitive interviewing (Willis, 1999) can assist in item and scale refinement. Quantitative research can be conducted to test hypothesized links between theory constructs among women who have experienced FGC, as shown in Figure 1. If descriptive research supports hypothesized links, interventions (e.g., decision aid tools, brief counseling modules) can be designed to deliver support to women who have undergone infibulation (Type III FGC). Content of interventions could potentially be tailored to specific attitudes, perceived norms, and perceptions of control endorsed by women on a screening tool. A focus on theoretically-informed and empirically supported determinants of deinfibulation may increase the likelihood that women will develop intentions to deinfibulate and choose to be deinfibulated. Additional details about the process of conducting qualitative and quantitative research to inform the development of interventions is described by Montaño and Kasprzyk (2015) in their chapter on the Theory of Planned Behavior, as well as precursors to and extensions of this theory.

Other theories and constructs can be considered along with the Theory of Planned Behavior, as appropriate. For example, the Stages of Change Model has been applied to assess readiness for change with respect to discontinuing the practice of FGC (Shell-Duncan & Hernlund, 2006; Andro & Lesclingand, 2016), and could be extended to readiness for deinfibulation. Among migrants and immigrants, acculturation is a construct that may impact the communities to which women feel a sense of belonging, as well as women’s attitudes, perceived norms, perceived control, and intentions with respect to deinfibulation. One might expect degree of acculturation to also be associated with women’s readiness for change in the practice of FGC, both in terms of discontinuing the practice among daughters and being receptive to deinfibulation if one has undergone Type III FGC.

Culturally Appropriate Clinical Care and Shared Decision-Making with Providers

Johansen and colleagues describe substantial variation across countries with respect to practices and policies guiding healthcare for communities who practice FGC, as well as the extent to which countries have monitoring and evaluation systems (Johansen, Ziyada, Shell-Duncan, Kaplan, & Leye, 2018). Practices and policies that vary include systematic training of healthcare providers, documentation of FGC in medical records, involvement of providers in prevention of FGC, provision of psychological counseling and sexual counseling for women who have experienced FGC, provision of deinfibulation, and prohibitions against FGC and reinfibulation. Variation in practices and policies may make it difficult for patients to navigate conversations about FGC when they have migrated to a new country. In addition, laws prohibiting the practice of FGC and attainment of FGC for daughters while traveling, permitting prosecution of parents and guardians who attain FGC for daughters, and mandating that providers report observed cases of FGC among children (e.g., Mishori, Warren, & Reingold, 2018) may make some patients reluctant to discuss FGC with providers. While a review of different countries and states’ laws, other policies, and practices with respect to FGC is beyond the scope of this article, providers should become familiar with the laws, policies, and practices within their region.

When women migrate to countries where FGC is not the norm, health care providers may unintentionally react to FGC in a way that makes women feel “othered,” abnormal, and lacking in health care options due to their FGC (e.g., assumption that a cesarean-section will be necessary during childbirth; Jacobson et al., 2018). To avoid alienating patients, health care providers should react calmly to observed FGC and acknowledge the importance of traditional beliefs and practices passed down from generation to generation. Health care providers should emphasize that their role is to provide information, share recommendations, and facilitate conversations that allow the patient to make decisions about her body that she judges to be in her best interests. When discussing infibulation, deinfibulation, reinfibulation, or any other stitching procedures (e.g., repair of vaginal tearing or episiotomies during childbirth), providers should show illustrations to minimize confusion and misunderstandings about the preferences of patients and their families.

The questions in Table 1, informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior, could be utilized as one tool to clarify the values of both patients and providers and make shared decisions. Whereas shared decision-making with family members may serve to enhance or diminish patients’ perceived control (Ho, 2008), shared decision-making with providers is intended to enhance patients’ perceived control and autonomy over their medical decision-making (Dugas et al., 2012; Légaré et al., 2008). Shared decision-making is a model of health care in which providers and patients openly discuss the risks and benefits of different health care options, reveal their preferences, and jointly make a decision (Dugas et al., 2012; Légaré et al., 2008). This model has been applied to support women’s decision-making in pregnancy and birth, and could be extended to the decision to deinfibulate among women who have undergone Type III FGC (infibulation).

Two features of the shared decision-making model are particularly well-suited to the decision to deinfibulate. One is the intent to shift the provider-patient relationship from one of paternalism to partnership (Dugas et al., 2012). By providing women with information and asking about their preferences, providers will reinforce and potentially enhance women’s perceptions of control over medical decision-making. This may assist some women in choosing to deinfibulate, despite their worry about going against the wishes of important referents (e.g., female elders). The second feature of shared decision-making that is well-suited to the decision to deinfibulate is the expectation that decisional conflict can emerge from the decision-making process, particularly if one party’s values and expectations cannot be met (Dugas et al., 2012). Because the shared decision-making model anticipates potential conflict between patients and health care providers, providers can prepare in advance for how they will handle conflict. Dugas and colleagues (2012) note that decision aid tools can be used to improve knowledge among patients while also decreasing decisional conflict between providers and patients.

Questions in Table 1 may also yield information about facilitators of and barriers to deinfibulation that could be addressed by the health care team. Tailored communication and support can be provided based on a woman’s responses to questions designed to assess theory constructs. For example, women may have negative attitudes towards the appearance of “open” genitalia. To allay concerns about the attractiveness of genital appearance, a provider can provide information about the great diversity in clitoral, labial, and vaginal characteristics that constitute female genital appearance (Berg et al., 2017), and frame this diversity as healthy and beautiful. As another example, women may perceive low control over medical decision-making and worry about going against the wishes of important referents, such as elder female relatives. In this instance, a provider can ask if there are other close individuals who would support the decision to deinfibulate, and whether the woman can show respect and regard for family members in other ways than remaining infibulated. In the spirit of shared decision-making, such tailored communication and support should be provided in a way that makes it clear that the provider will accept the woman’s decision, within the boundaries of the law and the provider’s medical ethics.

Depending on the degree to which a woman values the opinions and advice of individuals who are close to her (e.g., elder female relatives, husband) and shares control over medical decision-making with these individuals, health care providers can ask if the woman would like to invite these support sources to join the conversation during another appointment. Culturally sensitive inquiry about a partner’s or other family members’ views of deinfibulation may help a woman decide to choose deinfibulation. A health care provider may also wish to recommend individual, couple, or family counseling structured around discussion of Theory of Planned Behavior constructs.

Timing of Deinfibulation Relative to Pregnancy and Requests for Reinfibulation after Childbirth

While experts recommend that deinfibulation should be discussed with and offered to girls and women who have undergone Type III FGC regardless of pregnancy status (ACNM, 2017; ACOG, 2007; RCOG, 2015; Perron et al., on behalf of SOGC, 2013; WHO, 2016), pregnancy is likely to precipitate many conversations about deinfibulation between women and their health care providers. The World Health Organization (2018) recommends that deinfibulation not be performed during the first trimester of a pregnancy because there is a generally increased risk of spontaneous abortion during this time. If a spontaneous abortion occurs soon after a first-trimester deinfibulation, women may blame the procedure for the miscarriage, which in turn may lead communities to believe that deinfibulation is a dangerous procedure (WHO, 2018). When deinfibulation cannot occur prior to labor, providers should not attempt to avoid deinfibulation (also known as an anterior episiotomy) in favor of other procedures that facilitate childbirth (e.g., by instead electing for a different type of episiotomy or a cesarean-section as a first approach) (Johansen, 2006; Rodriguez, Seuc, Say, & Hindin, 2016, WHO, 2016; WHO, 2018). Rodriguez and colleagues (2016) note that while episiotomies can protect against anal sphincter tears and postpartum hemorrhage among women with Type III FGC, performing the smallest episiotomy necessary to achieve maternal or fetal gain is the best approach. Johansen (2006) distinguishes between deinfibulation, which involves opening the infibulation seal consisting of relatively thin, bloodless layers of skin, and other types of episiotomies, which involve cutting through relatively muscular and blood-filled tissues. She observes that some providers – in an attempt to be culturally sensitive – may conduct other types of episiotomies during childbirth instead of deinfibulation, when this is not in the best interests of the patient’s health.

Health care providers should also be prepared to address the issue of reinfibulation after childbirth. Providers may mistakenly believe that reinfibulation is desired and offer the procedure or complete the procedure without asking women if this is their preference (Almroth-Berggren et al., 2001; Berggren, Salam, Bergström, Johansson, & Edberg, 2004; Johansen, 2006). Reinfibulation should never be performed without an express request from the patient. When a request for reinfibulation is made, providers must act in accordance with the laws of their country or state and best practices endorsed by their profession, board, and institution. They may also need to examine their own ethical views in light of recommendations against reinfibulation advanced by the World Health Organization (2018) and several professional organizations, including the American College of Nurse-Midwives (2017), American Academy of Family Physicians (n.d.), Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Perron et al., on behalf of SOGC, 2013), and Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2015). The World Health Organization (2018) asserts that reinfibulation is a violation of women’s human rights and is never medically recommended. Similarly, the American College of Nurse-Midwives (2017) asserts that reinfibulation is a form of medicalized FGC and a violation of medical ethics. Both organizations judge the risks of reinfibulation to outweigh perceived benefits. The World Health Organization (2018) suggests that it would be “relatively simple” to respond to requests for reinfibulation by patients in countries where there are laws against reinfibulation, as providers can explain that the law does not permit re-suturing the labia together. In countries where there are no such laws, the World Health Organization (2018) suggests following guidelines of the medical institution, while also making every effort to discourage the practice of reinfibulation. Other organizations vary with respect to their guidance for the reinfibulation of adult women after childbirth upon their request. In 2007, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) observed that it was “vital to understand that … patients may have lived with infibulation for decades” and recommended that providers review applicable laws on FGC before performing reinfibulation. While ACOG has no current guidelines on reinfibulation, the American Academy of Family Physicians (2015) strongly cautions its members against performing reinfibulation and the Canadian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2013) has urged its members to decline requests for reinfibulation. The Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2015) of the United Kingdom warns its members that reinfibulation is illegal.

In regions of the world where laws do not prohibit reinfibulation and one’s profession, board, and institution(s) provide guidance that allows for different interpretations, providers must examine and act in concert with their own ethical views (Mishori, 2017). Some providers may draw a distinction between the ethics of “healing naturally” after childbirth versus being reinfibulated by the provider. Figure 1 refers to healing naturally after vaginal childbirth as “pseudo-reinfibulation” (Rushwan, 2000) because “natural healing” of scar tissue from FGC will likely lead to partial resealing (Figure 1, bottom center). Some providers may also draw a distinction between partial versus full reinfibulation after childbirth. Because the World Health Organization (2018) advises providers to decline requests for a “mini” deinfibulation, partial reinfibulation – which would be structurally similar to a “mini” deinfibulation – might be declined on the same ethical grounds.

It may be helpful for providers to discuss their views on deinfibulation and reinfibulation with colleagues, either informally or during organized forums on culturally appropriate care for women who have undergone FGC. Such forums may be sponsored by medical professional organizations, boards, and medical institutions. Conversations about deinfibulation should extend beyond care for pregnant women who are preparing for a vaginal childbirth to include the decision-making of women who have given birth through cesarean-section, as well as girls and women who have not experienced pregnancy. Conversations should address nuances in care that are likely to generate differences of opinion, such as the legality and ethics of providing girls and women with a “mini” deinfibulation or partial reinfibulation procedure, and allowing “pseudo-reinfibulation” to occur after childbirth.

Conclusion

To adhere to recommendations advanced by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) and numerous professional organizations (ACNM, 2017; ACOG, 2007; RCOG, 2015; Perron et al., on behalf of SOGC, 2013), providers should discuss and offer deinfibulation to female patients who have undergone Type III FGC. The World Health Organization (2016) has noted that research is urgently needed to understand factors that facilitate or act as barriers to deinfibulation. This article introduces a theoretically-informed conceptual model to guide future research and clinical conversations about FGC and deinfibulation with women who have undergone infibulation, as well as women’s partners and families. Without guidance in how to discuss FGC and deinfibulation in a manner that is sensitive to each patient’s culture, community, and values, providers risk offending and alienating their patients, which may in turn reduce the likelihood that girls and women choose to be deinfibulated. The conceptual model offered in this article applies the Theory of Planned Behavior to the decision to deinfibulate. Discussion of a woman’s attitudes, perceived norms, and perceived control may facilitate shared decision-making between providers and patients (Dugas et al., 2012; Légaré et al., 2008). The Theory of Planned Behavior may also guide future qualitative and quantitative research examining women’s intentions to be deinfibulated, which may in turn inform decision-making aids and other intervention tools that health care providers can utilize to better serve their patients.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this article was partially supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01HD091685-01A1) and the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Abdulcadir J, Marras S, Catania L, Abdulcadir O, & Petignat P (In Press). Defibulation: A visual reference and learning tool. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Almroth-Berggren V, Almroth L, Bergström S, Hassanein OM, El Hadi N, & Lithell U (2001). Reinfibulation among women in a rural area in central Sudan. Health Care for Women International, 22, 711–721. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Family Physicians. (AAFP). (n.d.). Female genital mutilation. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/genital-mutilation.html

- American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM). (2017). Position Statement: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. Retrieved from http://www.midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000068/FemaleGenitalMutilationCuttingMay2017.pdf

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2007). Female genital cutting: Clinical management of circumcised women (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: ACOG. [Google Scholar]

- Andro A, & Lesclingand M (2016). Translated by M. Grieve & P. Reeve. Les mutilations génitales féminines. État des lieux et des connaissances. [Female genital mutilation: Overview and current knowledge]. Population, 71, 217–296. [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Denison E, & Fretheim A (2010). Psychological, social and sexual consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): A systematic review on quantitative studies. Report from Kunnskapssenteret nr 13–2010. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Odgaard-Jensen J, Fretheim A, Underland V, & Vist GE (2014). An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the obstetric consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 542859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Taraldsen S, Said MA, Sorbye IK, & Vangen S (2017). Reasons for and experiences with surgical interventions for female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): A systematic review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14, 977–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Taraldsen S, Said MA, Sorbye IK, & Vangen S (2018). The effectiveness of surgical interventions for women with FGM/C: A systematic review. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125, 278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Underland V, Odgaard-Jensen J, Fretheim A, & Vist GE (2014). Effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal (BMJ) Open, 4 (11), e006316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren V, Salam GA, Bergström S, Johansson E, & Edberg A (2004). An explorative study of Sudanese midwives’ motives, perceptions and experiences of re-infibulation after birth. Midwifery, 20, 299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue CL (1995). The predictive capacity of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior in exercise research: An integrated literature review. Research in Nursing & Health, 18, 105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JJ, Hunt S, Finsaas M, Ciesinski A, Ahmed A, & Robinson BE (2016). Sexual Health Care, Sexual Behaviors and Functioning, and Female Genital Cutting: Perspectives from Somali Women Living in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 53(3), 346–359. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1008966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas M, Shorten A, Dube E, Wassef M, Bujold E, & Chaillet N (2012). Decision aid tools to support women’s decision making in pregnancy and birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1968–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp JA, & Ennett ST (1991). Conceptual models for health education research and practice. Health Education Research, 6, 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein G (2008). From body to brain: Considering the neurobiological effects of female genital cutting. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 51 (1), 84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan R (1997). Self-determination vs family-determination: Two incommensurable principles of autonomy. Bioethics, 11 (¾), 309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CM, Darlow K, Massie A, & Gorman DR (2018). Using electronic maternity records to estimate female genital mutilation in Lothian from 2010 to 2013. The European Journal of Public Health, 28 (4), 657–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, & Kok G (1996) The Theory of Planned Behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11 (2), 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graamans E, Ofware P, Nguura P, Smet E, & ten Have W (2018). Understanding different positions on female genital cutting among Maasai and Samburu communities in Kenya: A cultural psychological perspective. Culture, Health & Sexuality, DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1449890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griva F, Anagnostopoulos F, & Madoglou S (2009). Mammography screening and the Theory of Planned Behavior: Suggestions toward an extended model of prediction. Women & Health, 49, 662–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman CL, & Knowlden AP (2014). Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behavior-based dietary interventions in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 5, 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A, Grace KT, & Warren N (In Press). A meta-synthesis of the birth experiences of African immigrant women affected by female genital cutting. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A (2008). Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilo CI, Darfour-Oduro SA, Okafor JO, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Nwimo IO, & Onwunaka C (2018). Factors associated with parental intent not to circumcise daughters in Enugu State of Nigeria: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 22 91), 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivazzo C, Sardi TA, & Gkegkes ID (2013). Female genital mutilation and infections: A systematic review of the clinical evidence. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 287 (6), 1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson D, Glazer E, Mason R, Duplessis D, Blom K, Du Mont J, Jassal N, & Einstein G (2018) The lived experience of female genital cutting (FGC) in Somali-Canadian women’s daily lives. PLoS ONE, 13 (11), e0206886. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen REB (2002). Pain as a counterpoint to culture: toward an analysis of pain associated with infibulation among Somali immigrants in Norway. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 16 (3), 312–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen REB (2006). Care for infibulated women giving birth in Norway: An anthropological analysis of health workers’ management of a medically and culturally unfamiliar issue. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 20 (4), 516–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen REB (2017a). Undoing female genital cutting: Perceptions and experiences of infibulation, deinfibulation and virginity among Somali and Sudanese migrants in Norway. Culture, Health, & Sexuality, 19 (4), 528–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen REB (2017b). Virility, pleasure and female genital mutilation/cutting: A qualitative study of perceptions and experiences of medicalized deinfibulation among Somali and Sudanese migrants in Norway. Reproductive Health, 14 (1), 25 (12 pages). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen REB, Ziyada MM, Shell-Duncan B, Kaplan AM, & Leye E (2018). Health sector involvement in the management of female genital mutilation/cutting in 30 countries. BMC Health Services Research, 18 (1), 240. (13 pages). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Helm T, Killawi A, & Padela AI (2014). Perceptions of obstetrical interventions and female genital cutting: Insights of men in a Somali refugee community. Ethnicity & Health, 19 (4), 440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuther TL (2002). Rational decision perspectives on alcohol consumption by youth: Revising the Theory of Planned Behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, & Graham ID (2008). Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 73, 526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane A, & Dorkenoo E (2015). Prevalence of female genital mutilation in England and Wales: National and local estimates. City University London: London. [Google Scholar]

- Mishori R (2017, August 31). On reinfibulation: Part of the female genital mutilation/cutting discussion that rarely gets mentioned. Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/on-reinfibulation-part-of-the-female-genital-mutilation_us_59a85813e4b096fd8876c15e [Google Scholar]

- Mishori R, Warren N, & Reingold R (2018). Female genital mutilation or cutting. American Family Physician, 97 (1), 49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, & Kasprzyk D (2015). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (Eds.) Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice (5th ed., pp. 95–124). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2005). Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- National FGM Centre. (2017). Traditional Terms for Female Genital Mutilation. Retrieved from http://nationalfgmcentre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/FGM-Terminology-for-Website.pdf

- Parikh N, Saruchera Y, & Liao L (In Press). It is a problem and it is not a problem: Dilemmatic talk of the psychological effects of female genital cutting. Journal of Health Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashaei T, Ponnet K, Moeeni M, Khazaee-pool M, & Majlessi F (2016). Daughters at risk of female genital mutilation: Examining determinants of mothers’ intentions to allow their daughters to undergo female genital mutilation. PLoS ONE, 11 (3), e0151630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron L, Senikas V, Burnett M, & Davis V, on behalf of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). (2013). Female genital cutting. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 35 (11), e1–e18. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MI, Seuc A, Say L, Hindin MJ (2016). Episiotomy and obstetric outcomes among women living with type 3 female genital mutilation: a secondary analysis. Reproductive Health, 13 (1), 131. 10.1186/s12978-016-0242-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RCOG). (2015, July). Female genital mutilation and its management. Green-top Guideline No. 53. Retrieved from https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-53-fgm.pdf

- Rushwan H (2000). Female genital mutilation (FGM) management during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. International journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 70, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell-Duncan B, & Hernlund Y (2006). Are there “stages of change” in the practice of female genital cutting? African Journal of Reproductive Health, 10 (2), 57–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, & Stein K (2017). Surgical or medical interventions for female genital mutilation. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 136 (Suppl. 1), 43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tola G, & Moriano JA (2010). Theory of Planned Behavior and smoking: Meta-analysis and SEM model. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 1, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson M, Covey J, & Rosenthal HES (2014). Theory of Planned Behavior interventions for reducing heterosexual risk behaviors: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 33 (12), 1454–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. (2016). Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A global concern. UNICEF, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2015). Trends in International Migration, 2015. Population Facts. No. 2015/4. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. (2018). Female genital mutilation (FGM) frequently asked questions. Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/resources/female-genital-mutilation-fgm-frequently-asked-questions#FGM_terms

- USLegal. (n.d.) Right to autonomy and self determination. Retrieved from https://healthcare.uslegal.com/patient-rights/right-to-autonomy-and-self-determination/

- Viera AH, & Leles CR (2014). Exploring motivations to seek and undergo prosthodontic care: An empirical approach using the Theory of Planned Behavior construct. Patient Preference and Adherence, 8, 1215–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vloeberghs E, van der Kwaak A, Knipsheer J, & van den Muijsenbergh M (2012). Coping and chronic psychosocial consequences of female genital mutilation in the Netherlands. Ethnicity & Health, 17 (6), 677–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rege I, & Campion D (2017). Female genital mutilation: Implications for clinical practice. British Journal of Nursing, 26 (18), S22–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB (1999). Cognitive Interviewing: A “How To” Guide. Research Triangle Institute. Retrieved from http://www.chime.ucla.edu/publications/docs/cognitive%20interviewing%20guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Women in Balance Institute, National University of Natural Medicine, Portland, OR. https://womeninbalance.org/2017/03/14/female-genital-mutilation-and-clitoral-reconstructive-surgery [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2008). Eliminating Female genital mutilation: An interagency statement: OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Document Production Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Care of girls & women living with female genital mutilation: A clinical handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome. (2006). Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet, 367 (9525), 1835–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]