Abstract

To develop treatments for salivary gland dysfunction, it is important to understand how human salivary glands are maintained under normal homeostasis. Previous data from our lab demonstrated that murine salivary acinar cells maintain the acinar cell population through self-duplication under conditions of homeostasis, as well as after injury. Early studies suggested that human acinar cells are mitotically active, but the identity of the resultant daughter cells was not clear. Using markers of cell cycle activity and mitosis, as well as an ex-vivo EdU assay, we show that human salivary gland acinar cells divide to generate daughter acinar cells. As in mouse, our data indicate that human salivary gland homeostasis is supported by the intrinsic mitotic capacity of acinar cells.

Keywords: Salivary gland, EdU, Acinar, Human, Explant, Submandibular, Parotid, Ki67, PHH3, AURKB

Introduction

Salivary gland (SG) dysfunction is a common off-target side effect of radiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. This results in the loss of secretory acinar cells causing permanently decreased saliva production [1]. Current treatments for SG dysfunction are palliative. To restore long term function of the SG, a regenerative therapeutic approach is needed. The current focus in the pursuit of therapies for SG dysfunction is on identifying a source of cells to drive regeneration, characterization of signaling pathways important for maintaining the niche environment, and understanding the tissue interactions in the context of homeostasis and injury [reviewed in 2].

In the mouse, we have demonstrated that submandibular gland acinar cells are maintained and supported by acinar cell division under conditions of normal homeostasis and following injury [3,4]. Subsequent studies, using lineage tracing, support this finding, and indicated that the SG acinar and duct cell populations are maintained as separate lineages [4–7]. However, the mechanism whereby acinar cells are maintained in the human SG has not been firmly established.

Early studies of human SG tissue showed that cells in both the acinar and duct compartments are mitotically active [8]. It was suggested that the differentiated acinar cell population possesses an intrinsic regenerative capacity [8]. While these studies supported the hypothesis that differentiated acinar cells were capable of maintaining the SG acinar cell population, they lacked direct evidence. To determine whether human SG acinar cells undergo cell division to support the acinar cell population we stained for markers of cell cycle, mitosis, and DNA replication. We demonstrate that differentiated human SG acinar cells are mitotically active and give rise to daughter acinar cells. As hypothesized from earlier studies, our data indicate that the intrinsic mitotic capacity of human acinar cells supports homeostasis of the human SG [8].

Materials and Methods

Tissue collection

Adult human SG tissue was collected from both male and female patients undergoing neck dissection and surgical resection of non-malignant parotid (PG) or submandibular (SMG) gland tissue. All tissue was collected following informed consent. This study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board (RSRB00060088). Acquired tissue was rinsed in sterile PBS on ice and immediately dissected into 1–3mm3 pieces for fixation in 4% PFA or for explant culture.

Tissue culture

Human PG and SMG samples were immediately washed in sterile PBS warmed to 37°C to remove blood. Tissue was carefully sliced into ~2mm3 pieces using a sterile razor blade and forceps. Half of the tissue was placed in incubation media (DMEM (Gibco), 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% Pen-Strep, 1% L-Glutamine) with 10uM EdU (Roche), and the other half was incubated without EdU, as control, for 24 hours at 37°C, 20% O2, and 5% CO2. Tissue was then removed from culture and processed as described below.

Tissue processing

Tissue samples were washed in sterile PBS and subsequently fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C overnight. Fixed specimens were then rinsed twice with sterile PBS followed by an overnight incubation in 70% ethanol. After fixation, tissue was dehydrated and infiltrated with paraffin during a 4-hour protocol on a Sakura Tissue Tek-VIP tissue processing machine. Processed tissue samples were embedded in paraffin blocks prior to sectioning, rehydration, and staining.

Immunofluorescent staining

Tissue was sectioned at 5μm or 3μm (for AURKB staining) and allowed to dry. Sections were then deparaffinized and rehydrated prior to heat-induced epitope retrieval in 10mM Tris, 1mM EDTA buffer, pH 9.0, at 100°C in a pressure cooker for 10 minutes. Tissue was allowed to cool for 45 minutes prior to EdU detection or blocking with 10% natural donkey serum in 0.1% Bovine Serum Albumin in PBS (0.1% PBSA) for immunofluorescence staining. Primary antibodies, NKCC1 (1:100 goat SC-21545, 1:250 rabbit CST 85403), Mist1 (1:250 rabbit Abcam ab187978), E-Cadherin (1:250 BD 610181), phospho-histone H3 (1:500 or 1:1000 rabbit Millipore 06–570), aurora-B kinase (1:500 or 1:1000 rabbit Abcam ab2254), and Ki67 (1:500 mouse BD 550609) were applied overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies Alexa-fluor 594 α goat (Invitrogen, A11058), Alexa-fluor 594 α rabbit (Invitrogen, A21207), Alexa-fluor 488 α mouse (Invitrogen, A21202), Alexa-fluor 488 α rabbit (Invitrogen, A21207), and Alexa-fluor 488 α goat (Invitrogen, A11055) were applied at a dilution of 1:250 or 1:500 (for Ki67) in 0.1% PBSA and incubated in the dark at room temperature for one hour. DAPI (1:1000, Invitrogen, D1306) was applied for 5 minutes in 0.1% PBSA prior to mounting with Immu-Mount solution (Thermo, 9990402). Slides were allowed to dry overnight at 4°C prior to imaging.

Click-It EdU

Following antigen retrieval, EdU detection was performed using the Alexa-fluor 488 Click-IT EdU Plus kit (Thermo C10637), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunofluorescent staining was subsequently performed as described above.

Imaging and Analysis

Confocal imaging was performed using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope with a 40X oil immersion objective and Argon laser. Images were taken in stacks of 10 and combined as a series projection representing maximum intensity or 85–90% transparency using the Leica TCS software. Analysis of images was performed in ImageJ. Images were first inverted, converted to 8-bit format, thresholded to binary, and then the watershed function was used to distinguish between individual cells. The particle analysis plugin was used to automatically count binary nuclei. Thresholding was used to select and count all acinar cells based on NKCC1 or MIST1 expression. Ki67-positive cells were counted by two independent observers.

Images for EdU analysis were taken on an Olympus IX85 phase contrast microscope at 40X magnification. Images were merged and processed using Metamorph Basic prior to manual analysis using the cell counting plugin on ImageJ.

Data analysis

For each stain, five images were acquired from three slides of each tissue sample. To estimate the rates of cell division, among NKCC1+ cells, the ratio of the sum of all dividing cells for a given tissue sample (Ki67+ or EdU+) to the total number of cells for a given tissue sample was taken and an exact 95% confidence interval was applied. Confidence intervals for each subject were computed using `binom.test` in R 3.4.3 after aggregating cell counts across all slide-zones for a subject. To estimate the overall average rates and 95% credible intervals across subjects, a mixed effect binomial regression model was estimated using rstanarm version 2.17.3, with random effects for subject and zone-of-slide within subject. For hPG EdU, a total 150 slide zones from 5 subjects were analyzed; for hPG KI67+, a total 180 zones from 6 subjects were analyzed; for hSMG Ki67+ a total of 90 zones from 3 subjects were analyzed. In every case, 3 slides were made for each subject.

Results

Human tissue samples

Human PG and SMG samples were obtained from patients undergoing surgical excision of non-malignant SG tissue. In total, 14 hPG and 6 hSMG samples were collected. Sections from all samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to confirm normal SG tissue morphology (Supplemental Fig. S1). All tissues included in this study had non-pathological morphology with clearly discernable acinar and duct structures. All work with human samples was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Human salivary gland acinar cells are mitotically active

To determine whether human acinar cells are mitotically active, we stained tissue sections for the marker of mitotic activity, Ki67, in conjunction with acinar cell-specific markers (Fig. 1). We found that a population of cells in hPG and hSMG expressing MIST1 (BHLHA15), a transcription factor marking differentiated acinar cells, co-expressed Ki67 (Fig. 1A, B). Similarly, staining for the sodium-potassium-chloride channel 1 (NKCC1), a membrane protein expressed by acinar cells, revealed co-localization with Ki67 in some cells (Fig. 1C, D), as did staining for aquaporin 3 (AQP3), a membrane channel also specific to acinar cells (Fig. 1E, F). In support of these results, we used antibody to phosphohistone-H3 (PHH3). As the phosphorylation of histone H3 occurs in late G2 and M phase of the cell cycle, PHH3 serves as a specific marker for cells undergoing mitosis [9]. We found that a subset of acinar cells marked by NKCC1 expression were also stained with antibody to PHH3 (Fig. 1G, H).

Figure 1. Human salivary gland acinar cells are mitotically active.

Adult human salivary gland tissue sections were co-stained for markers of cell cycle activity and cell type-specific markers to identify mitotically active populations. (A) Human parotid gland (hPG) stained for the nuclear acinar cell marker, MIST1 (red), and the proliferation marker, Ki67 (green). (B) Human submandibular gland (hSMG) stained for MIST1 (red), and Ki67 (green). (C) hPG stained for the acinar cell membrane protein, NKCC1 (red), and Ki67 (green). (D) hSMG stained for NKCC1 (red), and Ki67 (green). (E) hPG stained for the acinar cell membrane marker, AQP3 (red), and Ki67 (green). (F) hSMG stained for the acinar cell membrane marker, AQP3 (red), and Ki67 (green). (G) hPG stained for the acinar cell membrane marker NKCC1 (green) and the proliferation marker, phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3) (red). (H) hSMG stained for the acinar cell membrane marker NKCC1 (green) and the proliferation marker, PHH3 (red). White asterisks indicate Ki67+ or PHH3+ acinar cells. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars =50 μm.

A significant population of human salivary gland acinar cells is mitotically active

We quantified the number of Ki67-positive acinar and duct cells, based on co-expression of NKCC1 (Fig. 1C, D), using automated image analysis of fluorescent confocal images. We used binomial mixed effect models to estimate the proportion of mitotically active acinar cells in hPG and hSMG. Analysis of the tissues from 6 subjects showed that an average of 0.3% acinar cells in hPG were mitotically active (95% credible interval [CI] 0.2%−−0.4%, Fig. 2A). Similarly, an average of 0.5% acinar cells in hSMG from 3 subjects were mitotically active (95% CI 0.1% -- 1.7%, Fig. 2B). The average percentage of Ki67-positive acinar cells was found to be greater than or equal to that of duct cells, supporting the conclusion that acinar cells in adult human SG are mitotically active (Fig. S2A–S2B).

Figure 2. Quantification of mitotically active cells in human salivary glands.

(A) Quantification of Ki67+ NKCC1+ acinar cells in hPG displayed as a percentage of the total NKCC1+ cell population. (B) Quantification of Ki67+ NKCC1+ acinar cells in hSMG displayed as a percentage of the total NKCC1+ cell population. Dots indicate the percentage of Ki67+ NKCC1+ cells from one of 5 images from three individual slides per sample. Circles represent sample averages from 15 total images with 95% confidence intervals.

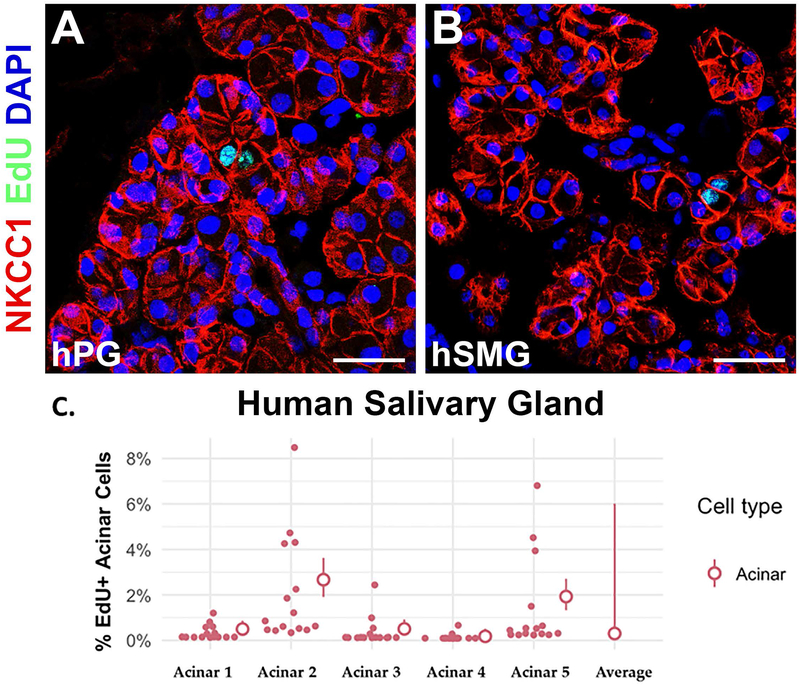

Human salivary gland acinar cells incorporate EdU in explant culture

As a secondary method to demonstrate that human acinar cells are mitotically active, hSMG and hPG tissue was incubated in ex vivo culture with media containing the thymidine analog, ethynyldeoxyuridine (EdU). Mitotically active cells should incorporate EdU during S-phase DNA replication. After 24 hours, the explant culture tissue was fixed, sectioned, and co-stained for NKCC1, and EdU. We found 0.3% (95% CI 0.2%−0.4%) and 0.7% (95% CI 0.1%−3.1%) of hPG and hSMG acinar cells, respectively, were labeled with EdU (Fig. 3). In agreement with Ki67 labeling, we found EdU incorporation of acinar cells to be greater than or equal to the duct cell population (Fig. S2C).

Figure 3. Human salivary gland acinar cells incorporate EdU in explant culture.

(A) Human PG incubated in explant culture with EdU for 24 hours, fixed and stained for EdU (green) and the acinar cell marker, NKCC1 (red). (B) Human SMG incubated with EdU in explant culture and stained for EdU (green) and the acinar cell marker, NKCC1 (red). White asterisks indicate EdU+ acinar cells. (C) Quantification of EdU+ NKCC1+ acinar cells in hPG and hSMG explant cultures displayed as a percentage of the total NKCC1+ cell population. Dots indicate the percentage of EdU+ NKCC1+ cells from one of 5 images from three individual slides per sample. Circles represent sample averages from 15 total images with 95% confidence intervals. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Human salivary gland acinar cells divide to generate acinar cell progeny

To determine whether human acinar cells are generated by self-duplication, we stained for the epithelial cell membrane marker, E-cadherin (E-cad), or the acinar cell markers NKCC1 and AQP3, in combination with Aurora Kinase B (AURKB). The expression of AURKB, an enzyme required for arrangement of the mitotic spindle, is regulated by cell cycle progression. Shortly after mitosis, the AURKB protein localizes to the cleavage site between two recently-divided cells [10]. Thus, staining with antibody to AURKB is used to detect related daughter cells. We found AURKB localized between cells labeled by E-cad, in both human (Fig. 4A,B) and mouse tissue (Supplemental Fig. S3). To confirm that the dividing cells generated differentiated acinar cell progeny, we co-stained sections of hPG and hSMG for AURKB and the acinar cell markers NKCC1 or AQP3. We found that AURKB foci were present between cells positive for AQP3 and NKCC1 (Fig. 4C,D), indicating that human acinar cells generate daughter cells through duplication.

Figure 4. Aurora kinase B is localized at cleavage site of recently divided human salivary gland acinar cells.

Human salivary gland tissue was stained for aurora kinase B (AURKB) (red), which localizes between two recently divided cells at the cleavage site shortly after mitosis, and epithelial cadherin (E-CAD) (green) or acinar cell membrane markers, NKCC1 or AQP3 (green). (A) hPG stained for AURKB (red) and E-CAD (green). (B) hSMG stained for AURKB (red) and E-CAD (green). (C) hPG stained for AURKB (red) and the acinar cell marker, NKCC1 (green). (D) hPG stained for AURKB (red) and the acinar cell marker, AQP3 (green). Inserts show 4X magnified AURKB foci between cells. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Discussion

In a previous study, we demonstrated that differentiated acinar cells in the adult mouse SMG are maintained through simple cell division, without detectable contribution from other cell populations [3]. The study demonstrated that the murine SG acinar cell population possesses an intrinsic proliferative capacity necessary for the maintenance of adult SG acinar cells under normal homeostasis. Furthermore, we showed that differentiated acinar cells have the potential to regenerate in mice following duct ligation or acute radiation injury [3,4]. Together, these results prompted us to investigate the hypothesis that differentiated acinar cells in the adult human SG possess intrinsic proliferative capacity and give rise to acinar daughter cells [8].

In agreement with previous studies, we show that human SG acinar cells possess a low, yet significant, capacity for proliferation [8]. Furthermore, the use of antibodies specific for cell cycle activity and for recent cell division allowed us to demonstrate that the proliferating cells generate differentiated acinar daughter cells.

Co-expression of the proliferation markers, Ki67 or PHH3, with acinar cell markers in samples of normal adult human PG and SMG demonstrated that acinar cells are actively cycling in adult human SG. We also found that adult human acinar cells incorporated EdU in explant cultures of both hPG and hSMG tissue. Notably, the range of 95% confidence intervals generated by quantification of the percentage of Ki67+ acinar cells was remarkably similar in the diverse human SG samples we collected. This consistency supports our conclusion that acinar cells remain mitotically active in adult human SG, and argues that the detection of mitotically active SG acinar cells cannot be attributed to specific genetic background or patient health history.

To demonstrate that acinar cells in human SG self-renew and give rise to daughter acinar cells, as shown in mice, we stained for AURKB. AURKB is a serine/threonine kinase crucial to successful cytokinesis, and staining with an antibody allows visualization of the spindle midbody both during and after cytokinesis [reviewed in 11]. Shortly after mitosis is completed, AURKB is localized at the cleavage site between the two daughter cells [10]. Taking advantage of this, AURKB has been used to identify daughter cells from cardiac myocyte and hepatocyte cell divisions [10,12]. We used AURKB staining in conjunction with E-Cadherin (an epithelial cell membrane marker), and the acinar cell-specific markers NKCC1 and AQP3, to definitively determine whether cycling acinar cells give rise to acinar daughter cells. We found AURKB foci in the membrane between acinar cells in both mouse and human adult SG tissue. This result confirms that under normal homeostasis human acinar cells generate acinar daughter cells, and supports the hypothesis that acinar cells in adult human SG are capable of maintaining the endogenous acinar cell population under normal homeostasis, as shown previously in mice.

While these results indicate that acinar cells can be maintained by cell division, we cannot rule out the possibility that other cell populations may contribute to the acinar cell population in human SGs. However, recent lineage studies conducted in our laboratory and by others have failed to find evidence that putative progenitor cell populations contribute to acinar cell replacement [4–7]. We have recently shown that duct cells exhibit lineage plasticity to replace acinar cells, but this occurs only under conditions of acute stress [4].

It is unclear whether proliferative capacity is intrinsic to the entire acinar cell population or is an attribute of a discrete subset of SG acinar cells. In our previous study, we used multicolor lineage tracing to determine whether murine acinar cells continue to proliferate [3]. Notably, in that study, we observed that a consistent population of labeled acinar cells did not divide, even after a 3-month chase time. Instead, they remained single labeled cells and did not give rise to a clone of more than one cell. These results suggested that the SG acinar cell population may not be homogenous with respect to proliferative capacity. Acinar cell heterogeneity has been demonstrated in the adult pancreas, where it was shown that only a minor subset of acinar cells retains proliferative ability [13]. Furthermore, heterogeneous expression of Sox2 distinguishes a subset of progenitor-like acinar cells which can facilitate regeneration in the secretory compartment of the sublingual gland (SLG) following injury [7]. As this population of Sox2 cells is only present in the SLG, future studies are required to determine whether acinar cells in the PG and SMG possess equivalent proliferative capacity.

In conclusion, our results firmly support the hypothesis that differentiated acinar cells in human SG possess intrinsic proliferative capacity to generate acinar daughter cells [8]. These data suggest that, as has been demonstrated in the mouse, human SG acinar cells may be maintained by self-duplication [3]. This finding raises the intriguing possibility that strategies to repair damaged SG could be based on the proliferation of residual acinar cells for regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Pei-Lun Weng and Dr. Abeer Shaalan for their valuable suggestions regarding the staining protocols used in this work; and Dr. Paul Allen for assistance with tissue procurement.

Funding Sources and Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR/NIH) R56DE025098 (CEO), NIDCR/NCI/NIH UG3DE02769501 (CEO); and by the Training Program in Oral Sciences, T90 DE021985 (MHI).

Abbreviations:

- SMG

Submandibular gland

- PG

Parotid gland

- hSMG

human submandibular gland

- hPG

human parotid gland

- mSMG

mouse submandibular gland

- mPG

mouse parotid gland

- PHH3

phospho-histone H3

- AURKB

aurora kinase B

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2´-deoxyuridine

- NKCC1

sodium potassium chloride channel 1

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicting interests.

References

- [1].Vissink A et al. (2010). Clinical Management of Salivary Gland Hypofunction and Xerostomia in Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients: Successes and Barriers. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 78, 983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aure MH, Symonds JM, Mays JW and Hoffman MP (2019). Epithelial Cell Lineage and Signaling in Murine Salivary Glands. Journal of Dental Research, 0022034519864592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aure MH, Konieczny SF and Ovitt CE (2015). Salivary Gland Homeostasis Is Maintained through Acinar Cell Self-Duplication. Developmental Cell 33, 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Weng PL, Aure MH, Maruyama T and Ovitt CE (2018). Limited Regeneration of Adult Salivary Glands after Severe Injury Involves Cellular Plasticity. Cell Rep 24, 1464–1470.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kwak M, Ninche N, Klein S, Saur D and Ghazizadeh S (2018). c-Kit+ Cells in Adult Salivary Glands do not Function as Tissue Stem Cells. Scientific Reports 8, 14193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Song EC, Min S, Oyelakin A, Smalley K, Bard JE, Liao L, Xu J and Romano RA (2018). Genetic and scRNA-seq Analysis Reveals Distinct Cell Populations that Contribute to Salivary Gland Development and Maintenance. Sci Rep 8, 14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Emmerson E et al. (2018). Salivary glands regenerate after radiation injury through SOX2-mediated secretory cell replacement. EMBO Mol Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ihrler S, Blasenbreu-Vogt S, Sendelhofert A, Rossle M, Harrison JD and Lohrs U (2004). Regeneration in chronic sialadenitis: an analysis of proliferation and apoptosis based on double immunohistochemical labelling. Virchows Arch 444, 356–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li DW, Yang Q, Chen JT, Zhou H, Liu RM and Huang XT (2005). Dynamic distribution of Ser-10 phosphorylated histone H3 in cytoplasm of MCF-7 and CHO cells during mitosis. Cell Research 15, 120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hesse M, Doengi M, Becker A, Kimura K, Voeltz N, Stein V and Fleischmann BK (2018). Midbody Positioning and Distance Between Daughter Nuclei Enable Unequivocal Identification of Cardiomyocyte Cell Division in Mice. Circ Res 123, 1039–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ruchaud S, Carmena M and Earnshaw WC (2007). Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 8, 798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Miyaoka Y, Ebato K, Kato H, Arakawa S, Shimizu S and Miyajima A (2012). Hypertrophy and unconventional cell division of hepatocytes underlie liver regeneration. Curr Biol 22, 1166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wollny D et al. (2016). Single-Cell Analysis Uncovers Clonal Acinar Cell Heterogeneity in the Adult Pancreas. Developmental Cell 39, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.