Abstract

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has shown satisfactory surgical results for the treatment of thoracic myelopathy (TM) caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF). This study investigated the prognostic factors following MIS and was based on the retrospective analysis of OLF patients who underwent percutaneous full endoscopic posterior decompression (PEPD). Thirty single-segment OLF patients with an average age of 60.4 years were treated with PEPD under local anaesthesia. Clinical data were collected from the medical and operative records. The surgical results were assessed by the recovery rate (RR) calculated from the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) score. Correlations between the RR and various factors were analysed. Patients’ neurological status improved from a preoperative mJOA score of 6.0 ± 1.3 to a postoperative mJOA score of 8.5 ± 2.0 (P < 0.001) at an average follow-up of 21.3 months. The average RR was 53.8%. Dural tears in two patients (6.7%, 2/30) were the only observed complications. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that a longer duration of preoperative symptoms and the presence of a high intramedullary signal on T2-weighted MRI (T2HIS) were significantly associated with poor surgical results. PEPD is feasible for the treatment of TM patients with a particular type of OLF. Patients without T2HIS could achieve a good recovery if they received PEPD early.

Subject terms: Spinal cord diseases, Neurosurgery, Risk factors

Introduction

Thoracic myelopathy (TM) is less common than cervical myelopathy and lumbar spinal stenosis1, and TM is mainly caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF) in East Asian countries, such as Japan, Korea, and China2. As the number of reported cases has increased, OLF has been studied not only in East Asia but also worldwide3–5. Although much of its pathophysiology has been determined, the exact pathogenetic mechanism and the epidemiology of OLF remain poorly understood6,7. Therefore, making an appropriate and timely therapeutic decision for the treatment of OLF may be hindered by the paucity of knowledge. TM caused by OLF remains a challenge for spine surgeons.

OLF generally requires posterior surgical decompression due to its progressive nature and poor response to conservative therapy8,9. Decompression procedures include traditional open surgeries, such as laminectomy with or without posterior fusion10,11, and minimally invasive surgery (MIS), such as microendoscopic decompression12,13 and percutaneous endoscopic decompression14–17. However, the prognostic guidelines are still unclear, and the surgical results vary widely despite complete decompression3,18.

To the best of our knowledge, all the published studies on prognostic factors in OLF patients have been based on traditional open surgery. However, MIS has been advantageous in treating OLF with satisfactory surgical results12,15–17. This study investigated the prognostic factors following MIS and was based on the retrospective analysis of OLF patients who underwent percutaneous full endoscopic posterior decompression (PEPD).

Materials and Methods

The Ethics Committee of Tangdu Hospital approved the study, and all patients signed informed consent. The methods described were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This was not a study commissioned or funded by any manufacturer.

Patient population

Between April 2016 and January 2018, thirty consecutive patients with TM caused by single-segment OLF underwent PEPD under local anaesthesia using the endoscopic system (iLESSYS®, Joimax® GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The indications for surgery were progressive muscle weakness in the lower extremities, gait disturbance, dorsal pain, and sphincter dysfunction. Neurological examinations and preoperative MRI/CT were performed to determine the location of OLF and the target area for decompression. OLF was classified into lateral, extended, enlarged, fusion, and tuberous types based on axial CT as well as round and beak types based on sagittal MRI19,20. Fusion and tuberous types of OLF were excluded based on the surgical difficulties in endoscopic decompression15. In addition, patients with ventral compression (thoracic disc herniation, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament), concomitant cervical or lumbar lesions and severe cardiopulmonary disease were also excluded. The clinical characteristics were recorded, including sex, age, the duration of preoperative symptoms, a history of smoking and comorbidities (diabetes mellitus or hypertension). The presence of a high intramedullary signal on T2-weighted MRI (T2HIS) was recorded. The location of the lesions was classified as upper (T1-T4), middle (T5-T8), and lower (T9-T12) on the basis of the thoracic spine level. The presence of intraoperative dural adhesion/dural ossification (DA/DO), operation time and estimated blood loss (EBL) were also recorded.

Clinical and radiologic assessments

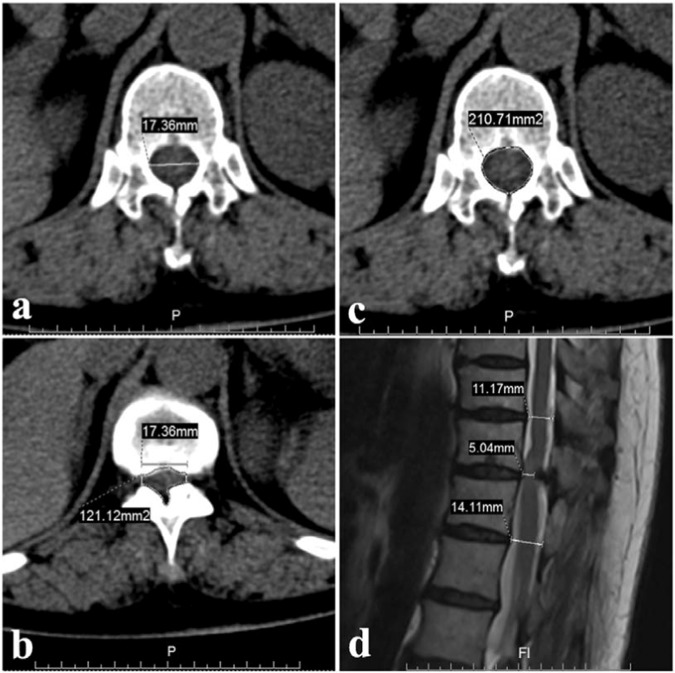

All patients were followed for at least one year. Pre- and postoperative neurological statuses were evaluated using the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) score (Table 1). The recovery rate (RR) = (postoperative mJOA-preoperative mJOA)/(11-preoperative mJOA) × 100%21. According to the RR, the surgical results were divided into good (50–100%), fair (25–49%), unchanged (0–24%), or deteriorated (<0%)22. The cross-section area (CSA) and the anteroposterior diameter (APD) of the spinal canal (Fig. 1) were measured on axial CT and sagittal T2-weighted MRI using the Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS). The CSA was measured as follows23: The widest distance between two pedicles as viewed on a CT scan was measured as the transverse spinal canal diameter (Fig. 1a), equal to the transverse spinal canal diameter at the maximally compressed CT scan. A vertical line extending through the endpoints of the transverse diameter determined the boundary of the spinal canal and was used to measure the compressed CSA (Fig. 1b). The normal CSA was measured on the pedicle section of the same vertebrae (Fig. 1c). The ratio of CSA = (the compressed CSA)/(the normal CSA) × 100%. The APD was measured at the compressed level and at two normal levels above and below the compressed level (Fig. 1d)6. The average value of the APD just above and below the affected segment was the normal APD. The ratio of APD = (the compressed APD)/(the normal APD) × 100%.

Table 1.

Summary of the mJOA scoring system for the assessment of thoracic myelopathy.

| Neurological status | Score |

|---|---|

| Lower-limb motor dysfunction | |

| No dysfunction | 4 |

| Lack of stability and smooth reciprocation of gait | 3 |

| Able to walk on flat floor with walking aid | 2 |

| Able to walk up/downstairs with handrail | 1 |

| Unable to walk | 0 |

| Lower-limb sensory deficit | |

| No deficit | 2 |

| Mild sensory deficit | 1 |

| Severe sensory loss or pain | 0 |

| Trunk sensory deficit | |

| No deficit | 2 |

| Mild sensory deficit | 1 |

| Severe sensory loss or pain | 0 |

| Sphincter dysfunction | |

| No dysfunction | 3 |

| Minor difficulty with micturition | 2 |

| Marked difficulty with micturition | 1 |

| Unable to void | 0 |

Figure 1.

The measurement of the CSA and APD on axial CT and sagittal MRI (case 21). (a) The widest distance between two pedicles as viewed on a CT scan was measured as the transverse spinal canal diameter, equal to the transverse spinal canal diameter at the maximally compressed CT scan. (b) A vertical line extending through the endpoints of the transverse diameter determined the boundary of the spinal canal and was used to measure the compressed CSA. (c) The normal CSA was measured on the pedicle section of the same vertebrae. (d) The APD was measured at the compressed level as well as at two normal levels above and below the compressed level.

Surgical techniques

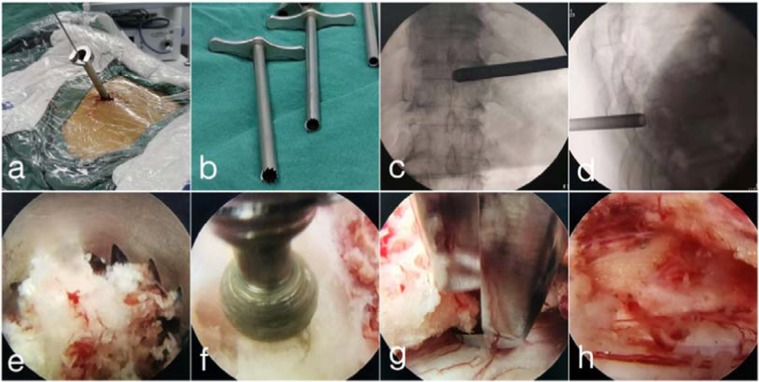

The patient was carefully arranged in the prone position. According to anaesthesiologists, dexmedetomidine (0.2–0.7 μg/kg/min) and sufentanil (0.1 μg/kg) were used to alleviate pain and maintain the sober situation. Patient feedback could be received promptly during the operation. The entry point in the skin was 5–6 cm from the midline. After the infiltration of local anaesthetics (0.5% lidocaine), an 18-gauge spinal needle was introduced under fluoroscopic guidance to the lamina on the root of the spinous process. Then, an approximately 10-mm skin incision was made, and the dilation catheter was inserted in sequence. A specially designed 8.5-mm diameter bevelled working cannula was placed, and a specially designed 7.5-mm diameter circular saw was placed through the cannula (Fig. 2a–d). Finally, the endoscope was placed through a circular saw, and laminotomy was achieved under the view of the endoscope (Fig. 2e). The unossified ligamentum flavum (LF) and soft tissue were removed by forceps and radiofrequency. Diamond abrasors were used to grind the contralateral ossified LF into a thin and translucent shape (Fig. 2f), and then Endo-Kerrison punches were used to remove the remnant ossified LF (Fig. 2g). The ipsilateral lesion was treated in the same manner. The whole procedure utilized the technique of “over-the-top” decompression15. Finally, the dural sac was exposed, and pulsation of the dural sac improved (Fig. 2h). Notably, tight DA/DO should be maintained but completely isolated from the surrounding LF to avoid a dural tear15. After complete decompression, the cannula was removed, and the incision was closed without the use of a suction drain.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative views of PEPD (case 21). (a,b) A specially designed bevelled working cannula was placed, and a specially designed circular saw was placed through the cannula. (c,d) Fluoroscopic views of the circular saw. (e) Laminotomy was achieved via the circular saw under the view of the endoscope. (f) Diamond abrasor was used to grind the contralateral ossified LF into a thin and translucent shape. (g) Endo-Kerrison punch was used to remove the remnant ossified LF. (h) The dural sac was exposed, and pulsation of the dural sac improved.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 18; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Student’s t-tests and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare the statistical significance of the association for continuous data. Pearson’s rank correlation coefficients were used to test the correlations between various factors and the RR. Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the quantitative variables that best correlated with the surgical results. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Qualitative data were converted to numbers for quantitation as follows24: (1) Sex: male, 1; female, 2. (2) Location of lesion: upper, 1; middle, 2; lower 3. (3) CT classification: lateral, 1; extended 2; enlarged 3. (4) MRI classification: round 1; beak 2. (5) Diabetes mellitus (DM): absent, 1; present 2. (6) Hypertension: absent, 1; present 2. (7) History of smoking: absent, 1; present 2. (8) T2HIS: absent, 1; present 2. (9) Intraoperative DA/DO: absent, 1; present 2.

Results

Clinical characteristics

This study included 17 male patients and 13 female patients with an average age of 60.4 (44–84) years. The patients’ symptoms included weakness and paraesthesia in the lower extremities, gait instability, claudication and sphincter dysfunction. Hyperreflexia occurred in all patients. The average duration of preoperative symptoms was 17.4 (0.4–40) months. Three patients (10.0%) were diagnosed with DM, 13 patients (43.3%) with hypertension, and 7 patients (23.3%) with a history of smoking before surgery.

Radiographical findings

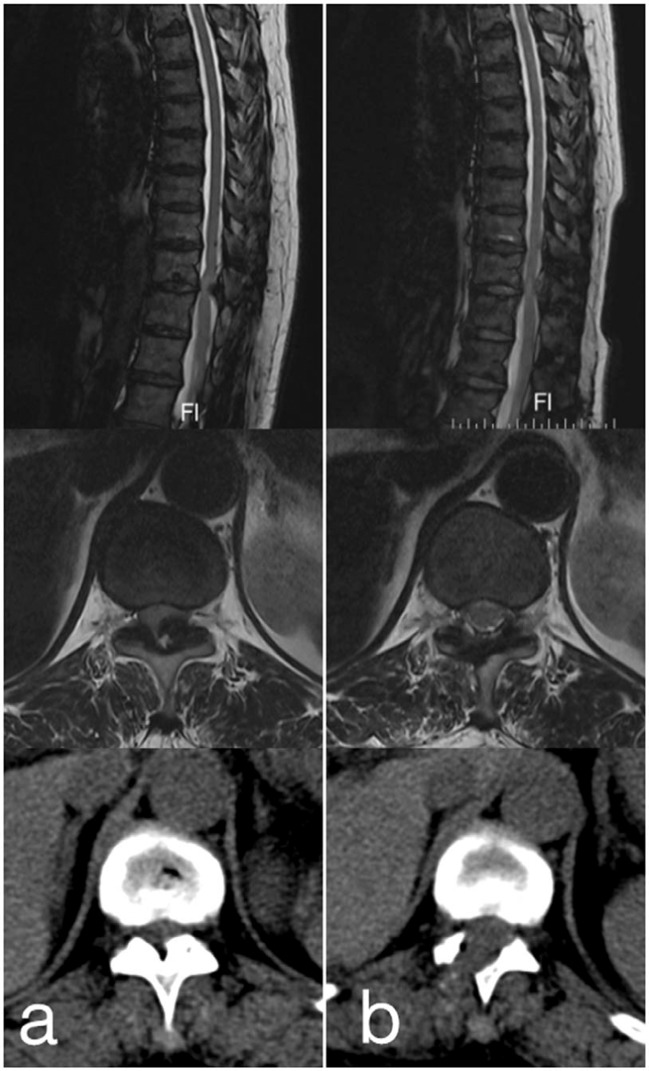

There were 24 lesions (80%) located at the lower thoracic spine, 4 lesions (13.3%) at the middle, and 2 lesions (6.7%) at the upper. According to axial CT images, 3 cases (10.0%) were classified as lateral type, 3 (10.0%) cases were extended type, and 24 (80.0%) cases were enlarged type. According to the sagittal MRI images, 20 cases (66.7%) were classified as round type, and 10 (33.3%) were classified as beak type. T2HIS was observed in 16 cases (53.3%). The mean APD and CSA of the normal thoracic canal were 11.6 (7.7–17.4) mm and 167.0 (110.1–296.0) mm2, and the mean APD and CSA of the compressed level were 5.4 (3.3–8.9) mm and 109.1 (66.3–195.9) mm2. The mean ratios of the APD and CSA were 47.3% and 66.2%, respectively. According to the pre- and postoperative CT and MR images, decompression was completed successfully by PEPD with a dome-shaped laminotomy through limited laminectomy and flavectomy (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Pre- and postoperative images of PEPD (case 21). (a) Sagittal MRI, axial MRI and CT revealed the OLF at T11/12 and the compressed spinal cord. (b) Satisfactory decompression was completed with a dome-shaped laminotomy through limited laminectomy and flavectomy.

Surgical outcome

In general, patients’ neurological status improved from a preoperative mJOA score of 6.0 ± 1.3 to a postoperative mJOA score of 8.5 ± 2.0 points (P < 0.001) at an average follow-up time of 21.3 months, yielding an average RR of 53.8%. According to the RR, 16 (53.3%) cases were classified as good, 7 (23.3%) cases were fair, 7 (23.3%) cases were unchanged, and 0 cases were deteriorated. The mean operation time was 167.0 (100–240) minutes. The mean EBL was 36.2 (25.0–50.0) ml. During PEPD, we found DA/DO in 11 (36.7%) patients, in whom 2 patients (cases 8 and 18) experienced dural tears, yielding an overall incidence of 6.7% (2/30). However, the two patients did not receive repair or indwelled drainage. They healed after staying in a prone position for one week with a pressure dressing. Neither cerebrospinal fluid cysts nor incision dehiscence occurred during their follow-up. No neurological deficits or other complications occurred in this study.

Relationship of the RR to various factors

Univariate analysis revealed that a poor RR was significantly related to a longer duration of symptoms, a lower preoperative mJOA score, a lower ratio of APD, a lower ratio of CSA, the presence of DM, the presence of T2HIS, and the presence of intraoperative DA/DO (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between the recovery rate and various factors.

| Factor | N | RR (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 17 | 45.4 ± 30.3 | 0.102 |

| Female | 13 | 64.7 ± 31.6 | ||

| Location of lesion | Upper | 2 | 70.0 ± 42.4 | 0.191 |

| Middle | 4 | 77.2 ± 29.7 | ||

| Lower | 24 | 48.5 ± 30.6 | ||

| CT classification | Lateral | 3 | 46.0 ± 27.6 | 0.305 |

| Extended | 3 | 80.6 ± 17.3 | ||

| Enlarged | 24 | 51.4 ± 32.8 | ||

| MRI classification | Round | 20 | 50.6 ± 31.8 | 0.447 |

| Beak | 10 | 60.1 ± 32.7 | ||

| DM | No | 27 | 56.7 ± 32.2 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 3 | 27.5 ± 9.0 | ||

| Hypertension | No | 17 | 55.3 ± 36.5 | 0.766 |

| Yes | 13 | 51.7 ± 25.8 | ||

| History of smoking | No | 23 | 55.7 ± 34.3 | 0.562 |

| Yes | 7 | 47.5 ± 22.7 | ||

| T2HIS | No | 14 | 74.7 ± 24.7 | 0.000 |

| Yes | 16 | 35.4 ± 25.7 | ||

| Intraoperative DA/DO | No | 19 | 67.3 ± 29.0 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 11 | 30.4 ± 22.0 | ||

| Age at surgery | R = −0.301 | 0.106 | ||

| Duration of symptoms | R = −0.729 | 0.000 | ||

| Preoperative mJOA score | R = 0.455 | 0.011 | ||

| Operation time | R = 0.219 | 0.245 | ||

| EBL | R = 0.145 | 0.443 | ||

| Ratio of APD | R = 0.661 | 0.000 | ||

| Ratio of CSA | R = 0.553 | 0.002 |

aCT denotes computed tomography; bMRI denotes magnetic resonance imaging; cDM denotes diabetes mellitus; dT2HIS denotes high intramedullary signal on T2-weighted MRI; eDA denotes dural adhesion; fDO denotes dural ossification; gmJOA denotes modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association; hEBL denotes estimated blood loss; iAPD denotes anteroposterior diameter; jCSA denotes cross-section area.

Prognostic factors related to the surgical results

Multiple linear regression analysis showed that a longer duration of preoperative symptoms and the presence of T2HIS were significantly associated with a poor RR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent factors associated with recovery rate.

| Factor | Partial regression coefficient (B) | Standardized partial regression coefficient (Beta) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100.301 (constant) | |||

| Sex | 2.117 | 0.034 | 0.853 |

| Age at surgery | −0.272 | −0.085 | 0.521 |

| History of smoking | −2.926 | −0.040 | 0.822 |

| DM | −25.975 | −0.249 | 0.166 |

| Hypertension | 15.421 | 0.244 | 0.082 |

| Duration of symptoms | −1.114 | −0.430 | 0.013 |

| Preoperative mJOA score | 3.130 | 0.132 | 0.435 |

| Location of lesion | −8.789 | −0.161 | 0.246 |

| CT classification | 3.330 | 0.068 | 0.745 |

| MRI classification | −3.134 | −0.047 | 0.719 |

| T2HIS | −27.950 | −0.445 | 0.012 |

| Ratio of APD | 0.267 | 0.077 | 0.654 |

| Ratio of CSA | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.978 |

| Operation time | 0.076 | 0.101 | 0.507 |

| EBS | 0.407 | 0.102 | 0.437 |

| Intraoperative DA/DO | −1.184 | −0.018 | 0.923 |

aDM denotes diabetes mellitus; bmJOA denotes modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association; cCT denotes computed tomography; dMRI denotes magnetic resonance imaging; eT2HIS denotes high intramedullary signal on T2-weighted MRI; fAPD denotes anteroposterior diameter; gCSA denotes cross-section area; hEBL denotes estimated blood loss; iDA denotes dural adhesion; jDO denotes dural ossification.

Discussion

Percutaneous endoscopic surgery, which is the most minimally invasive spinal surgery, can achieve decompression of spinal stenosis based on improvements in equipment and optical technology25. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study about the prognostic factors of OLF treated by MIS and the largest study about the surgical results of PEPD for the treatment of OLF. We found that PEPD was feasible for the treatment of thoracic OLF, and OLF patients without T2HIS could achieve a good recovery if they received PEPD early.

OLF mostly occurs in the lower thoracic spine and mostly affects male adults aged 40 to 60 years7,24,26–28. We found similar results, and our data showed that 56.7% (17/30) of the patients were male, 53.3% (16/30) were less than 60 years of age, and 80% (24/30) had decompression at the lower thoracic spine. In this study, patients’ neurological status improved significantly after PEPD, and the average RR was 53.8%, which is comparable to the 16–58.7% reported by several studies6,24,27,29,30.

Patients may suffer kyphosis after traditional open laminectomy because of the removal of bone tissue and destruction of the posterior tension band18,31,32. Posterior instrument fusion is recommended but still controversial. Yu et al. found that the overall mean increase in kyphosis was only 2.9° at a minimum of 1 year after surgery in 49 OLF patients, and no patient required additional surgery due to spinal deformity24. Aizawa et al. suggested that there was no relationship between surgical outcomes and an increased kyphotic angle after laminectomy31. In addition, thoracic kyphosis might be influenced by changes in back extensor strength in particular, and providing strong, natural extrinsic support for the spine seems to be important for decreasing the incidence of spinal deformities33. Percutaneous endoscopic surgeries minimize damage to the paraspinal muscles, facet joints, lamina and posterior ligamentous complexes15. We believe that OLF patients who undergo PEPD without fusion may have a much lower risk of kyphosis, and we will continue to conduct a control study to verify this point.

There is great interest in surgical techniques that can minimize complications. Recently, a meta-analysis showed a moderately high rate of perioperative complications after laminectomy for OLF, and the incidence of dural tears, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks, infections, and early neurological deficits were 18.4%, 12.1%, 5.8%, and 5.7%, respectively34. It is promising that the incidence of complications reported in MIS has been much lower12,15. The incidence of dural tears was only 6.7% (2/30) in this study. Since the diameter of punches and forceps used in PEPD was very small and the endoscopic visualization of anatomical structures in a liquid environment was very clear, endoscopic manipulation was so gentle that dural tears could be avoided as much as possible. However, tight DA/DO should remain in situ as a floating adherent fragment12,15.

Several studies have reported that some factors might affect the surgical results of OLF, including the duration of preoperative symptoms, preoperative neurological status, intramedullary signal changes in T2WI, age, sex, type of OLF, and dural tears3,7,20,27,30,35–37. However, it is still uncertain whether these factors are predictive of the surgical results following MIS.

The duration of preoperative symptoms was confirmed to be significantly correlated with the surgical results in our study, which is consistent with many studies3,19,29,35,38,39. We believe that the exacerbation of preoperative neurological status over a long time is mostly irreversible. Thus, earlier surgical intervention might result in better clinical outcomes, regardless of traditional laminectomy or MIS.

The presence of T2HIS was confirmed to be significantly correlated with surgical results in our study, which is similar to some studies7,30. Intramedullary signal changes in the spinal cord occur during pathologic changes, such as the loss of nerve cells, oedema, gliosis, demyelination, and Wallerian degeneration40,41. We believe that patients with intramedullary signal changes have irreversible spinal cord changes. As the symptoms are subjective, objective findings, such as radiologic examinations, are important for evaluating the factors that affect surgical results30.

The severity of myelopathy before surgery, which is mostly indicated by the preoperative mJOA score, was shown to be the most important predictor of surgical results in many studies3,24,36,38,41–43. However, few studies found a significant correlation between the preoperative mJOA score and RR according to multiple regression analysis3,36,41, and one study even showed no significant correlation between them in the univariate analysis1. Of note, we did not find a significant correlation between the preoperative mJOA score and RR in multiple regression analysis, similar to some studies24,29,38. A lower preoperative mJOA score may result in worse recovery, but it is not a predictor of the surgical results following PEPD.

The morphology of OLF might affect the surgical results but is still controversial. Kuh et al. suggested that the beak type of OLF with high intramedullary signal changes might be a poor prognostic factor20. However, Kang et al. found that patients with beak type OLF could achieve satisfactory RRs and considered that localized compression of the spinal cord could be corrected better than diffuse compression of a round type OLF42. Previous studies showed that the RR was significantly better in non-fused compression patients than in fused patients according to axial CT images6. However, Li et al. found that the axial CT configurations (unilateral, bilateral or bridged) were not significantly related to the surgical results41. Ando et al. also found that there were no statistically significant differences in the RR among the five OLF types (lateral, extended, enlarged, fused, and tuberous)27, which was similar to our results.

As the degree of compression increases, the stress distribution on the spinal cord increases. Our data showed that the ratio of APD and CSA had a negative influence on recovery in the univariate analysis, which is consistent with some studies24,29. However, we did not find any statistical correlation between the RR and the ratio of APD/CSA in multiple regression analysis. According to the surgical criteria of PEPD15, we excluded the fusion and tuberous types of OLF, which both tend to have poor surgical results because of the severe compression to the spinal cord and the low APD/CSA ratio6,19,24. The insufficient types of OLF in this study might make it difficult for us to draw significant correlations between the RR and the APD/CSA ratio, as well as between the RR and the types of OLF.

OLF located in the middle thoracic spine may be a predictor of poor outcome24. The middle thoracic spine, as the watershed area of the spinal circulation, has the narrowest canal and the maximal kyphotic angle. Thus, the spinal cord in the middle thoracic spine had insufficient compensatory space during posterior decompression, and there is a much greater risk of iatrogenic injury and ischaemic damage44. However, we did not find a significant correlation between the location of the lesion and RR. In our study, all four patients (cases 8, 17, 23, 28) with OLF located in the middle thoracic spine achieved satisfactory surgical results (good, fair, good, and good). PEPD showed features including small trauma, high safety (local anaesthesia), and fine and accurate manipulation15. It is advantageous to use PEPD to treat OLF, especially to treat OLF located in the middle thoracic spine.

Thoracic OLF is commonly associated with other spinal disorders, such as disc herniation and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Vascular injury is more likely to occur in anterior lesions such as OPLL, which could result in more severe myelopathy and worse recovery regardless of the less severe stenosis28,44. Therefore, we excluded patients with coexisting spinal conditions because their therapeutic decisions were more complicated and the surgical results were more unpredictable6,41.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of a control group which considered as the gold standard, such as the laminectomy. If the control group was established, the significance of this research would be greatly strengthened. We had started to conduct a retrospective case-control study in which laminectomy is used as a control group, and relevant data were being collected and analyzed. In addition, it was a retrospective study with a relatively small number of patients, and only included single-segment and incomplete types of OLF patients, which could have an impact on the adequacy of our results and could have weakened the statistical significance. Nonetheless, we believe that our results may provide preliminary data in support of the guidelines for PEPD to treat OLF. We will continue to refine this minimally invasive approach.

Conclusions

PEPD, as the most minimally invasive spinal decompression surgery, is feasible for the treatment of TM patients with a particular type of OLF. A longer preoperative duration of symptoms and the presence of T2HIS were significantly associated with poor surgical results following PEPD. Patients without T2HIS could achieve a good recovery if they received PEPD early.

Author contributions

Li X.C., An B. and Qian J.X. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study; Li X.C. and An B. performed the statistical analyses and collected the data; Gao H.R., Zhou C.P. and Zhao X.B. drafted parts of the manuscript; Ma H.J., Wang B.S., Yang H.J. and Zhou H.G. participated in drafting the article and interpreting the data; and An B., Gao H.R., Guo X.J., Zhu H.M. and Qian J.X. critically revised the article content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xingchen Li and Bo An.

References

- 1.Onishi E, et al. Outcomes of Surgical Treatment for Thoracic Myelopathy: A Single-institutional Study of 73 Patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:E1356–E1363. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ki AD, et al. Ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Asian Spine Journal. 2014;8:89–96. doi: 10.4184/asj.2014.8.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He S, et al. Clinical and prognostic analysis of ossified ligamentum flavum in a Chinese population. J. Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:348–354. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.5.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffan I, et al. Unusual CT/MR features of putative ligamentum flavum ossification in a North African woman. Br. J. Radiol. 2006;79:e67–e70. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15381140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohindra S, et al. Compressive myelopathy due to ossified yellow ligament among South Asians: analysis of surgical outcome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon SH, et al. Clinical analysis of thoracic ossified ligamentum flavum without ventral compressive lesion. Eur. Spine J. 2011;20:216–223. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1515-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inamasu J, Guiot BH. A review of factors predictive of surgical outcome for ossification of the ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:133–139. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhaddar A, et al. Thoracic spinal cord compression by ligamentum flavum ossifications. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69:319–323. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(02)00400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiura I, et al. Surgical approach to ossification of the thoracic yellow ligament. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:368–372. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(98)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia LS, et al. En bloc resection of lamina and ossified ligamentum flavum in the treatment of thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:1181–1186. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000369516.17394.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirabayashi H, et al. Surgery for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baba S, et al. Microendoscopic posterior decompression for the treatment of thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum: a technical report. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:1912–1919. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikuta K, et al. Decompression procedure using a microendoscopic technique for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2011;54:271–273. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia ZQ, et al. Transforaminal endoscopic decompression for thoracic spinal stenosis under local anesthesia. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:465–471. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An B, et al. Percutaneous full endoscopic posterior decompression of thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:492–501. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-05866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miao X, et al. Percutaneous Endoscopic Spine Minimally Invasive Technique for Decompression Therapy of Thoracic Myelopathy Caused by Ossification of the Ligamentum Flavum. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiaobing Z, et al. “U” route transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic thoracic discectomy as a new treatment for thoracic spinal stenosis. Int Orthop. 2018;43:825–832. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4145-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okada K, et al. Thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Clinicopathologic study and surgical treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:280–287. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aizawa T, et al. Thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum: clinical features and surgical results in the Japanese population. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:514–519. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.6.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuh SU, et al. Contributing factors affecting the prognosis surgical outcome for thoracic OLF. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:485–491. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0903-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirabayashi K, et al. Operative results and postoperative progression of ossification among patients with ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6:354–364. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li M, et al. Management of thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament combined with ossification of the ligamentum flavum-a retrospective study. Spine J. 2012;12:1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng F, Sun C, Chen Z. A diagnostic study of thoracic myelopathy due to ossification of ligamentum flavum. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:947–954. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu S, et al. Surgical results and prognostic factors for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of ligamentum flavum: posterior surgery by laminectomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:1169–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sairyo K, Chikawa T, Nagamachi A. State-of-the-art transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic lumbar surgery under local anesthesia: Discectomy, foraminoplasty, and ventral facetectomy. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang N, et al. Epidemiological survey of ossification of the ligamentum flavum in thoracic spine:CT imaging observation of 993 cases. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:857–862. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ando K, et al. Predictive factors for a poor surgical outcome with thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum by multivariate analysis: a multicenter study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:E748–E754. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828ff736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park BC, et al. Surgical outcome of thoracic myelopathy secondary to ossification of ligamentum flavum. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanghvi AV, et al. Thoracic myelopathy due to ossification of ligamentum flavum: a retrospective analysis of predictors of surgical outcome and factors affecting preoperative neurological status. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi Y, et al. Variables affecting postsurgical prognosis of thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Spine J. 2013;13:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aizawa T, et al. Sagittal alignment changes after thoracic laminectomy in adults. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:510–516. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/6/510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang T, et al. Surgical Technique for Decompression of Severe Thoracic Myelopathy due to Tuberous Ossification of Ligamentum Flavum. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30:E7–E12. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mika A, Unnithan VB, Mika P. Differences in thoracic kyphosis and in back muscle strength in women with bone loss due to osteoporosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:241–246. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000150521.10071.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osman NS, et al. Outcomes and Complications Following Laminectomy Alone for Thoracic Myelopathy due to Ossified Ligamentum Flavum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:E842–E848. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiokawa K, et al. Clinical analysis and prognostic study of ossified ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:221–226. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.94.2.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JK, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Factors in Patients With Myelopathy Caused by Thoracic Ossification of the Ligamentum Flavum. Neurospine. 2018;15:269–276. doi: 10.14245/ns.1836128.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang C, et al. Predictive factors for neurological deterioration after surgical decompression for thoracic ossified yellow ligament. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:2598–2605. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyakoshi Naohisa, Shimada Yoichi, Suzuki Tetsuya, Hongo Michio, Kasukawa Yuji, Okada Kyoji, Itoi Eiji. Factors related to long-term outcome after decompressive surgery for ossification of the ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2003;99(3):251–256. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.3.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang UK, et al. Surgical treatment for thoracic spinal stenosis. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:362–369. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi M, et al. Chronic cervical cord compression: clinical significance of increased signal intensity on MR images. Radiology. 1989;173:219–224. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.1.2781011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcome of thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum: a retrospective analysis of 85 cases. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:188–196. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang KC, et al. Ossification of the ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine in the Korean population. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:513–519. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.SPINE10405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao CC, et al. Surgical experience with symptomatic thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:34–39. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.1.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Min JH, Jang JS, Lee SH. Clinical results of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) of the thoracic spine treated by anterior decompression. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:116–119. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318060091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]