Abstract

This study aimed to genetically and clinically characterize a unique cohort of 25 individuals from 21 unrelated families with autosomal recessive nanophthalmos (NNO) and posterior microphthalmia (MCOP) from different ethnicities. An ophthalmological assessment in all families was followed by targeted MFRP and PRSS56 testing in 20 families and whole-genome sequencing in one family. Three families underwent homozygosity mapping using SNP arrays. Eight distinct MFRP mutations were found in 10/21 families (47.6%), five of which are novel including a deletion spanning the 5′ untranslated region and the first coding part of exon 1. Most cases harbored homozygous mutations (8/10), while a compound heterozygous and a monoallelic genotype were identified in the remaining ones (2/10). Six distinct PRSS56 mutations were found in 9/21 (42.9%) families, three of which are novel. Similarly, homozygous mutations were found in all but one, leaving 2/21 families (9.5%) without a molecular diagnosis. Clinically, all patients had reduced visual acuity, hyperopia, short axial length and crowded optic discs. Retinitis pigmentosa was observed in 5/10 (50%) of the MFRP group, papillomacular folds in 12/19 (63.2%) of MCOP and in 3/6 (50%) of NNO cases. A considerable phenotypic variability was observed, with no clear genotype-phenotype correlations. Overall, our study represents the largest NNO and MCOP cohort reported to date and provides a genetic diagnosis in 19/21 families (90.5%), including the first MFRP genomic rearrangement, offering opportunities for gene-based therapies in MFRP-associated disease. Finally, our study underscores the importance of sequence and copy number analysis of the MFRP and PRSS56 genes in MCOP and NNO.

Subject terms: Hereditary eye disease, Molecular medicine

Introduction

Congenital microphthalmia (MCO) is a heterogeneous developmental eye disease characterized by small, hyperopic eyes secondary to several etiological factors affecting the early formation of the optic cup1–3. MCO has a reported incidence of approximately 15/100,000 live births per year4 and may be isolated, complex or syndromic based on the presence or absence of associated ocular malformations and systemic involvement2,5. Moreover, MCO can be subclassified into two clinical subtypes called nanophthalmos (NNO) and posterior microphthalmia (MCOP), based on the involvement (NNO) or not (MCOP) of the anterior segment6,7. Both NNO and MCOP may be associated with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), foveoschisis and optic disc drusen8–10.

Clinically both conditions are characterized by a short axial length that gives rise to high hyperopia ranging between +8.00 to +25.00 diopters11. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) is reduced and rarely better than 20/4012–15. This poor BCVA is primarily caused by the hyperopia but may be aggravated by posterior segment changes such as an abnormal foveal structure and so-called papillomacular folds, uveal effusion, and an abnormal foveal avascular zone13,16. Patients with NNO or MCOP are prone to complications such as angle closure glaucoma, uveal effusion after intra-ocular surgery, non-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and intraretinal cysts13,16–18.

Biallelic mutations in the MFRP (encoding membrane-type frizzled related protein, MIM 606227) or PRSS56 (encoding protease serine 56, MIM 613858) genes have been reported to cause autosomal recessive NNO or MCOP. MFRP19,20 was found to be expressed predominantly in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and ciliary epithelium of the eye, with a weak expression in fetal brain3. Mouse and zebrafish studies confirmed its expression in the RPE and ciliary body20. Zebrafish models recapitulated reduced axial length causing hyperopia, reduced visual acuity and RPE folding21. Apart from its role in eye development and emmetropization, MFRP plays a role in photoreceptor maintenance, explaining the risk for RP-like changes when mutated8,22,23. PRSS56 was found to be expressed in human neural retina, cornea, sclera, and the optic nerve. Mouse Prss56 is expressed in the eye from embryonic development until adult life17. Mouse studies and genome-wide association studies suggest that PRSS56 is taking part of a regulatory network influencing postnatal eye development and emmetropization24–26.

Here, we aimed to genetically and clinically characterize 25 individuals from 21 unrelated families with autosomal recessive NNO or MCOP from different ethnicities, representing the largest cohort reported to date. This revealed eight distinct MFRP and six distinct PRSS56 mutations respectively, providing a molecular diagnosis in 19/21 families (90.5%) and uncovering opportunities for gene-based therapies in MFRP-associated disease.

Methods

Patients and clinical assessment

Twenty-five patients out of 21 unrelated families from different ethnicities with either isolated or complex NNO or MCOP were recruited from three centers: Ghent University Hospital, Belgium (n = 11); Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, UK (n = 7); and Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK (n = 7) (Table 1). A full ophthalmological examination included BCVA measurement and dilated fundus examination. Retinal fundus imaging was obtained by conventional 30-degree fundus colour photographs (Topcon Great Britain Ltd, Berkshire, UK) or via ultra-wide field confocal scanning laser imaging (Optos plc, Dunfermline, UK), near-infrared and blue light fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering Ltd, Heidelberg, Germany), and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering Ltd, Heidelberg, Germany). Full-field electroretinography (ERG) was performed according to the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standards27 (using either Roland Consult, Brandenburg an den Havel, Germany or Diagnosys, Cambridge, UK equipment). Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA blood using standard procedures. This study was conducted following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients from 21 unrelated families with isolated or complex NNO or MCOP.

| FA# | PT# | Extended ID | Sex | Ethnicity/Consanguinity | Age (year) | Group | Gene | BCVA, logMAR (Snellen) | Posterior segment features | AL (mm) | Posterior coat thickness (mm) | Refraction (diopter) | ERG | Diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | L | Crow-ded discs | Papillo-macular fold | Macular edema | White dots | Perip-heral pigment | R | L | R | L | |||||||||||

| F1 | P1 | B03271 | F | Belgian/Consanguineous | 23 | Ghent | MFRP | 0.6 | 0.3 | + | + | + | + | + | 16.1 | 15.7 | NA | NA |

R + 14,00 /−0,50 × 13 L + 15,50 /−0,25 × 117 |

SN | NNO/RP |

| F2 | P2 | B14785 | M | Moroccan/Consanguineous | 3 | Ghent | MFRP | 0.4 | 0.5 | + | + | - | + | - | 14.5 | 14.4 | NA | NA |

R+12.00 / + 1.00 × 180 L + 12.00/ + 1.00 × 180 |

SN | MCOP |

| F3 | P3 | GC19623 | F | Indian/NA | 29 | London | MFRP | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | - | + | - | - | 13.3 | 12.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

R + 15.25/−0.25 × 175 L + 15.25/−0.50 × 155 |

NL | MCOP |

| F4 | P4 | GC19691 | F | British Caucasian/NA | 15 | London | MFRP | 0.2 | 0.3 | + | + | - | + | + | 15.5 | 15.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

R + 16.00/−0.5 × 50 L + 16.00/−0.5 × 100 |

SN | MCOP |

| F5 | P5 | B09352 | F | Dagestanian/Consanguineous | 68 | Ghent | MFRP | 0.3 | 0.1 | + | - | + | + | + | 16.5 | 16.5 | NA | NA |

R + 8,50 /−1,00 × 106 L + 8,75 /−0,75 × 113 |

NR | NNO/RP |

| F6 | P6 | GC18886 | M | Kurdish/NA | 31 | London | MFRP | 0.8 | 0.6 | + | - | + | - | + | 16.5 | 16.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

R + 17.5/−0.50 × 95 L + 16.00/−0.50 × 90 |

NA | MCOP/RP |

| F7 | P7 | GC20271 | F | Iranian/NA | 51 | London | MFRP | 0.6 | 1.3 | + | - | + | - | + | NA | NA | NA | NA |

R + 15.0/−1.00 × 100 L + 15.5/−0.75 × 110 |

SN | MCOP/RP |

| F8 | P8 | B10315 | M | Italian/NA | 26 | Ghent | MFRP | LP | LP | + | - | + | + | - | 15.7 | 15.7 | NA | NA |

R +15.25/−0.25 × 175 L + 15.25/−0.50 × 155 |

SN | NNO/RP |

| F9 | P9 | B16796 | F | Belgian/NA | 75 | Ghent | MFRP | 0.1 | 0.1 | + | - | + | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA |

R+17,00/ 0,75 × 15 L + 15,00/ −0,75 × 170 |

SN | MCOP |

| F10 | P10 | B08047 | M | Moroccan/Consanguineous | 8 | Ghent | MFRP | 0.25 | 0.25 | + | - | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

R + 13.75 L+13.25 |

NA | NNO |

| F11 | P11 | GC20258 | F | British Caucasian/NA | 18 | London | PRSS56 | 0.6 | 0.3 | + | - | - | + | - | 15.7 | 15.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 | R + 15.00/−0.5 × 180 L + 13.50/−0.75 × 180 | NL | MCOP |

| F12 | P12 | GC18588 | M | Pakistani/NA | 37 | London | PRSS56 | 0.5 | 0.6 | + | + | + | + | - | 15.4 | 15.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

R + 2/−1.25 × 180 L + 4.5/−1.5 × 180 |

SN | MCOP |

| F13 | P13 | GC16899 | M | Somalian/NA | 20 | London | PRSS56 | 0.6 | 0.6 | + | + | + | + | - | 16.5 | 16.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

R + 15.00/−0.75 × 110 L + 15.50/−0.50 × 75 |

SN | MCOP |

| F14 | P14 | GC19721 | M | Pakistani/NA | 23 | London | PRSS56 | 0.8 | 0.8 | + | + | - | + | - | 15.9 | 15.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

R + 9.50/−1.00 × 20 L + 11.00/−1.00 × 40 |

SN | MCOP |

| F15 | P15 | RXK-4624916 | F | Pakistani/Consanguineous | 44 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | NA | NA | + | + | - | - | + | 17 | 17 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

R + 15.00 L + 15.50 |

NA | MCOP/RP |

| P16 | RXK-3297132 | M | Pakistani/Consanguineous | 13 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.2 | 0.1 | + | + | - | + | + | 15.2 | 15.6 | NA | NA |

R + 14.00 L + 14.50 |

NL | MCOP/RP | |

| P17 | RXK-33447157 | F | Pakistani/Consanguineous | 8 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.6 | 0.6 | + | - | - | + | - | 14.0 | 14.2 | NA | NA |

R + 16.00 L + 18.50/−1.00 × 10 |

SN | MCOP | |

| P18 | RXK-3113374 | F | Pakistani/Consanguineous | 12 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | + | - | - | - | 14.8 | 14.6 | NA | NA |

R + 15.50/−1.50 × 30 L + 14.50/−1.00 × 8 |

SN | MCOP | |

| P19 | RXK-4633376 | F | Pakistani/Consanguineous | 17 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | - | - | - | - | 14.5 | 14.5 | NA | NA |

R + 16.00/−1.00 × 180 L + 15.00/−1.00 × 180 |

NL | MCOP | |

| F16 | P20 | RXK-4941281 | M | Mirpuri/Consanguineous | 7 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.5 | 0.1 | + | + | - | - | - | 16.0 | 16.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

R + 16.25/−1.00 × 180 L + 17.25/−1.75 × 180 |

NA | MCOP |

| F17 | P21 | RXK-4985235 | F | Mirpuri/Consanguineous | 10 | Birmin-gham | PRSS56 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | + | - | - | - | 15.0 | 15.1 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

R + 19.50 L + 19.50 |

NA | MCOP |

| F18 | P22 | B05802 | M | Turkish/Consanguineous | 4 | Ghent | PRSS56 | 0.3 | 0.3 | + | + | + | - | - | 15.3 | 15.1 | NA | NA |

R + 14,25/ −0,50 × 4 L + 15,00 /−0,50 × 174 |

NL | MCOP |

| F19 | P23 | B01921 | M | Bulgarian/NA | 26 | Ghent | PRSS56 | 0.4 | 0.5 | + | + | + | - | - | 14.8 | 14.6 | NA | NA |

R + 15.25/−0.25 × 175 L + 15.25/−0.50 × 155 |

SN | NNO |

| F20 | P24 | B03421 | M | Belgian/NA | 7 | Ghent | / | 0.3 | 0.4 | + | + | + | - | - | 14.5 | 14.5 | NA | NA |

R + 14,25 /−1.00 × 13 L + 15,25 /−1.75 × 173 |

NL | MCOP |

| F21 | P25 | B07457 | M | Belgian/NA | 8 | Ghent | / | 0.2 | 0.2 | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

R NA L NA |

NA | NNO |

Abbreviations used: FA#: family number; PT#: patient number; NR: not-reported; AL: axial length; BCVA: best-corrected visual acuity; ERG: electroretinogram; F: female; L: left eye; M: male; mm: millimeters; NA: not available; NL: normal limit; NR: non-recordable; R: right eye; SN: subnormal; “/”: no mutation identified; + : presence; −: absence; MCOP: isolated posterior microphthalmia; MCOP/RP: posterior microphthalmia with RP; NNO: isolated nanophthalmos; NNO/RP: nanophthalmos with RP; retinitis pigmentosa: RP.

Homozygosity mapping

Homozygosity mapping using genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) arrays was performed in three patients originating from a self-reported consanguineous marriage, using HumanCytoSNP-12 BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Homozygous regions (>1 Mb) were identified using PLINK28 software integrated in ViVar29. Resulting homozygous regions were ranked according to their length and number of SNPs, as described30.

Mutation screening by Sanger sequencing and by whole genome sequencing

Primers for PCR amplification of the coding region and splice site junctions of MFRP and PRSS56 were designed (available upon request). Sanger sequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BigDyeTerminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, ABI 3730XL genetic analyzer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

One family (F7.GC20271) was included in a whole genome sequencing (WGS) study. Genome enrichment was performed using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample preparation kit (Illumina, Inc.), followed by sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 with a minimum coverage of 15x for approximately 95% of the genome. The Isaac Genome Alignment Software (version 01.14; Illumina, Inc.) was used for reads mapping against the Genome Reference Consortium human genome build 37 (GRCh37)31. Standard variant filtering was performed as previously described32,33. Structural variant (SV) assessment was done by interrogation of copy number variation (CNV), SV calls and visual inspection of the individual split and chimeric reads (Integrated Genome Viewer, IGV) across the breakpoints as described by Carss et al.32. A genomic rearrangement found in MFRP (GRCh37 [hg19] chr11:119, 217, 130_119, 223, 310delinsACCACTA, NM_031433.3) was confirmed using a junction PCR followed by Sanger sequencing of the junction product and by characterization of the breakpoint junctions.

Variant interpretation

Variant classification was performed following ACMG guidelines34. Using Alamut Visual (v. 2.7) (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France), following in silico prediction tools were used: Align GVGD, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant [SIFT], MutationTaster, and PolyPhen-2, Grantham score calculation, conservation. Several genomic databases including dbSNP build 145 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) and gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org) were used to assess variant frequencies in a general population. Segregation analysis was performed in all available family members. Mutation nomenclature uses numbering with the A of the initiation codon ATG as +1 (http://varnomen.hgvs.org/) based on the following RefSeqs: NM_031433.3 (MFRP) and NM_001195129.1 (PRSS56).

Results

Novel and known variants in MFRP and PRSS56

Homozygosity mapping in three families with a reported consanguineous background revealed the presence of MFRP in homozygous regions of 10.2 Mb and 6.2 Mb in two families (F1 and F2) respectively, while PRSS56 was found in a homozygous region of 6.5 Mb in the third family (F18) (Fig. S1). Subsequent testing of the MFRP and PRSS56 genes revealed three distinct homozygous mutations in these families, two of which are novel (Table 2). Direct testing of MFRP and PRSS56 in 17 families revealed 11 additional distinct mutations in MFRP and PRSS56, five of which are novel (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variant assessment of the identified MFRP and PRSS56 mutations in 21 unrelated families with NNO or MCOP.

| FAM. PID | Diagnosis | Gene | cDNA | Protein | Geno-type | Exon | Segregation | Grantham distance | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 | GVGD | Mutation Taster | gnomAD (Total population frequency) | ACMG Classifi-cation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

F1. |

NNO/RP | MFRP | c.1090_1094del | p.(Thr364Glnfs*26) | HOM | 9 | NP | / | / | / | / | / |

0.0004102% (0 HOM) |

Class 4 | This study |

|

F2. |

MCOP | MFRP | c.498del | p.(Asn167Thrfs*25) | HOM | 5 | Yes | / | / | / | / | / |

0.0004024% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | 20,38,44,45,52 |

|

F3. GC19623 |

MCOP | MFRP | c.1549C > T | p.(Arg517Trp) | HOM | 13 | NP | 101 | D |

Prob. dam. |

C25 |

Dis. caus. |

0.002022% (0 HOM) |

Class 4 | 41 |

|

F4. GC19691 |

MCOP | MFRP |

c.491_492insT 2nd variant unknown |

p.(Asn167Glnfs*34) | HTZ | 5 | NP | / | / | / | / | / |

0.005723% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | 36 |

|

F5. |

NNO/ RP |

MFRP | c.498dup | p.(Asn167Glnfs*34) | HOM | 5 | NP | / | / | / | / | / |

0.005723% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | 8,36,41 |

|

F6. GC18886 |

MCOP/ RP |

MFRP | c.1231T > C | p.(Tyr411His) | HOM | 10 | NP | 83 | D |

Prob. dam. |

C0 |

Dis. caus. |

Absent | Class 3 | This study |

|

F7. GC20271 |

MCOP/ RP |

MFRP | c.955C > T | p.(Gln319*) | HTZ | 8 | / | / | / | / | / | / | Absent | Class 5 | This study |

| c.6087_54 +40delinsTAGTGGT | none | HTZ | 5′UTR & 1 | / | / | / | / | / | / | Absent | ? | This study | |||

|

F8. |

NNO/ RP |

MFRP | c.498del | p.(Asn167Thrfs*25) | HOM | 5 | NP | / | / | / | / | / |

0.0004024% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | 36,39,42,48 |

|

F9. |

MCOP | MFRP | c.1090_1094del | p.(Thr364Glnfs*26) | HOM | 9 | Yes | / | / | / | / | / |

0.0004102% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | This study |

|

F10. |

NNO | MFRP | c.498del | p.(Asn167Thrfs*25) | HOM | 5 | Yes | / | / | / | / | / |

0.0004024% (0 HOM) |

Class 5 | 36,39,42,48 |

|

F11. GC20258 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | c.833dup | p.(Val279Argfs*2) | HTZ | 7 | NP | / | / | / | / | / | Absent | Class 5 | 49 |

| c.1571del | p.(Val525Cysfs*55) | HTZ | 13 | NP | / | / | / | / | / | Absent | Class 5 | This study | |||

|

F12. GC18588 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | c.1066dupC | p.(Gln356Profs*152) | HOM | 9 | NP | / | / | / | / | / | Absent | Class 5 | 17,51,53 |

|

F13. GC16899 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | c.320G > A | p.(Gly107Glu) | HOM | 4 | NP | 98 | D |

Poss. dam. |

C25 |

Dis. caus. |

0.009375% (0 HOM) |

Class 3 | This study |

|

F14. GC19721 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | c.1555G > C | p.(Gly519Arg) | HOM | 13 | NP | 125 | D |

Prob. dam. |

C0 |

Dis. caus. |

Absent | Class 4 | 53 |

|

F15. RXK4624916 |

MCOP/ RP |

PRSS56 | HOM | Yes | |||||||||||

|

F15. RXK3297132 |

MCOP/ RP |

HOM | |||||||||||||

|

F15. RXK33447157 |

MCOP | HOM | |||||||||||||

|

F15. RXK3113374 |

MCOP | HOM | |||||||||||||

|

F15. RXK4633376 |

MCOP | HOM | |||||||||||||

|

F16. RXK4941281 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | HOM | Yes | |||||||||||

|

F17. RXK4985235 |

MCOP | PRSS56 | HOM | Yes | |||||||||||

|

F18. |

MCOP | PRSS56 | c.766T > C | p.(Cys256Arg) | HOM | 7 | Yes | 180 | D |

Prob. dam. |

C0 |

Dis. caus. |

Absent | Class 4 | This study |

|

F19. |

NNO | PRSS56 | c.766T > C | p.(Cys256Arg) | HOM | Yes | |||||||||

|

F20. |

NNO | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

|

F21. |

NNO | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

Abbreviations used: FAM. PID: Family. Patient ID; HOM: homozygous; HTZ: heterozygous; NNO: isolated nanophthalmos; MCOP: isolated posterior microphthalmia; RP: retinitis pigmentosa; MCOP/RP: posterior microphthalmia with RP; NNO/RP: nanophthalmos with RP; /: no mutation identified; NP: not performed; D: deleterious; Prob. Dam.: probably damaging; Poss. Dam.: possibly damaging; Dis. Caus.: disease causing; Class 3: uncertain significance; Class 4: likely pathogenic; Class 5: pathogenic.

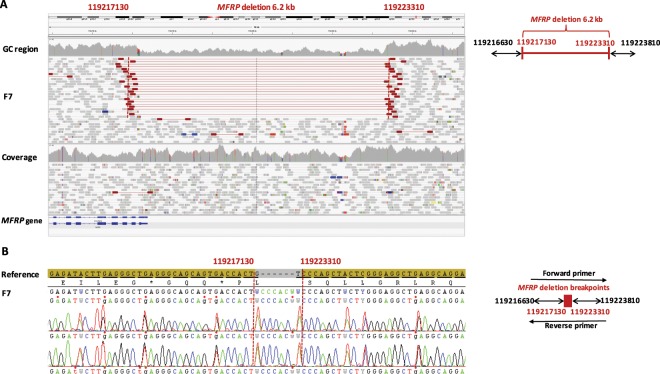

WGS in one family (F7) revealed two novel heterozygous mutations in MFRP: a coding nonsense variant c.955C > T p.(Gln319*) and genomic rearrangement consisting of a deletion of 6.2 kb and an insertion of 7 nucleotides c.−6087_54 +40delinsTAGTGGT p.(?). This genomic rearrangement encompasses the 5′UTR and the coding part of exon 1 and is predicted to abolish the transcription initiation site (Fig. 1A). The breakpoints of this deletion were characterized by a junction PCR followed by sequencing (Fig. 1B). An assessment of the breakpoints at the nucleotide level showed the insertion of seven base pairs (TAGTGGT), representing a potential information scar. As no microhomology was detected at the breakpoints and only one breakpoint overlapped with an Alu repeat, non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) and microhomology-based mechanisms are unlikely. Altogether, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is the most likely mechanism underlying this rearrangement35–37.

Figure 1.

Heterozygous copy number variation implicating MFRP found by whole genome sequencing. The affected patient in family 7 (F7) with MCOP and RP-like changes carries a partial MFRP deletion. (A) Left panel: IGV plot generated by whole genome sequencing, showing a heterozygous deletion of 6.2 kilobases (kb) and an insertion of 7 base pairs (bps) (GRCh37 [hg19] chr11:119, 217, 130_119, 223, 310delinsACCACTA, NM_031433.3 MFRP: c.−6087_54 +40 delinsTAGTGGT; p.?). Highlighted red read pairs have an unusually large insert size suggestive of a large deletion, and the read depth is reduced across the heterozygous deletion. The deletion spans exon 1 of MFRP probably abolishing transcription. Right panel: schematic representation of the deletion. (B) The deletion was confirmed by junction PCR and Sanger sequencing. The arrows in the schematic left panel represent the positions of the primers.

Overall, genetic defects were found in 19 of the 21 families (90.5%): eight distinct MFRP mutations in ten families (10/21, 47.5%) and six distinct PRSS56 mutations in nine families (9/21, 42.9%). Biallelic mutations were found in 18 families, while a monoallelic MFRP mutation was found in one family, with an undiscovered second mutation. With mutations neither in MFRP nor PRSS56, two Belgian families (2/21, 9.5%) remained molecularly unaccounted for. A summary of all variants identified, their in silico assessment and ACMG variant classification can be found in Table 2. Flowchart of the molecular workflow and outcomes is provided in Fig. S2.

Phenotypic characteristics

Twenty-five patients from 21 unrelated families were investigated, six with a diagnosis of NNO and 19 with MCOP. The age of diagnosis varied from 3–75 years. Overall, all eyes had an axial length of <18 mm and hyperopia of >8 diopters with crowded discs and foveal hypoplasia. The clinical features of all studied individuals are summarized in Table 1. Based on the genotypes found, the families were divided into two genetic subtypes: a MFRP- and PRSS56-associated group.

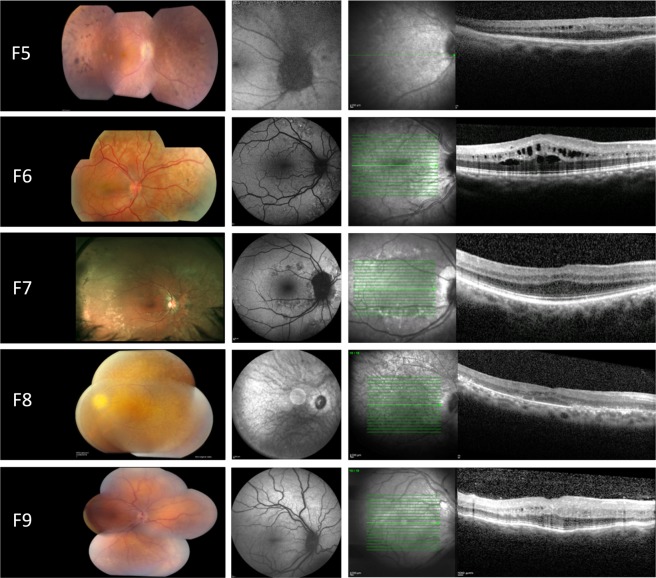

MFRP group. All affected individuals had reduced BCVA ranging from 0.1 logMAR to light perception. All had crowded discs and loss of normal foveal architecture. In 3/10 (30%) of the patients, there was evidence of papillomacular folds and intraretinal cysts. Moreover, peripheral retinal pigmentary changes were observed in 5/10 (50%) patients, ranging from mild RPE hypopigmentation to extensive reticular hypopigmentation and occasional hyperpigmented lesions. ERG was performed on 8/10 (80%) of MFRP-mutated patients, showing subnormal ERG responses for rod and cones in 6/8 (75%) of the patients P1, P2, P4, P7, P8 and P9), a non-recordable ERG in 1/8 (12.5%) (P5) and normal ERG responses in 1/8 (12.5%) (P3). Representative retinal imaging of these individuals is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Retinal imaging from the right eye of patients with NNO or MCOP due to mutations in MFRP. Left panel: color fundus. Middle panel: fundus autofluorescence imaging (FAF). Right panel: optical coherence tomography (OCT). F5: color fundoscopy showing crowded optic disc, mid-peripheral intraretinal hyperpigmentation with corresponding hypo-autofluorescence on FAF, foveal hypoplasia and intraretinal cystic cavities on OCT. F6: mid-peripheral hypopigmentary retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) changes with corresponding hyper- and hypo-autofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence imaging (FAF), cystic macular cavities on optical coherence tomography (OCT). F7: posterior pole and mid-peripheral hyper- and hypo-pigmentary RPE change with corresponding hyper- and hypo-autofluorescence on FAF, thickened OCT with foveal hypoplasia. F8: color fundoscopy with crowded optic disc, slight peripheral intraretinal hyperpigmentation and large posterior pole white dots corresponding with hyper- and hypo-autofluorescence on FAF imaging, foveal hypoplasia and cystic macular cavities on OCT. F9: color fundoscopy showing crowded optic disc and normal autofluorescence on FAF imaging, thickened OCT with foveal hypoplasia and occasional intraretinal cyst.

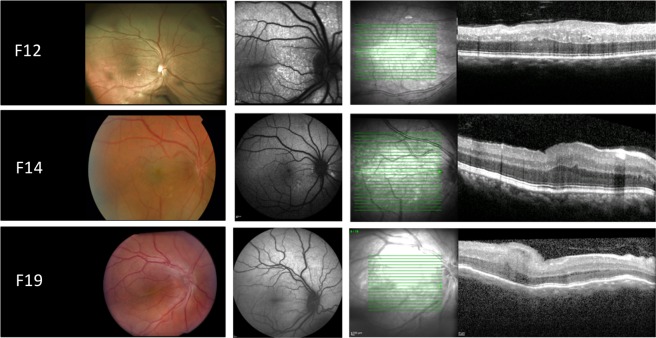

PRSS56 group. All affected individuals had reduced BCVA ranging from 0.1 to 0.8 logMAR. Crowded discs, loss of normal foveal architecture and papillomacular folds were observed in 7/13 (53.8%) patients. Peripheral retinal pigmentary changes were only found in two affected siblings (P15 and P16) (2/13, 15.4%). ERG was performed on 9/13 (69.2%) patients, showing subnormal ERG recordings in 5/13 (71.4%) (P12, P13, P14, P17 and P18), whereas normal responses were found in 4/13 (30.8%) (P11, P16 and P19 and P22). Representative retinal imaging of these individuals is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Retinal imaging from the right eye of patients with NNO or MCOP due to mutations in PRSS56. Left panel: color fundus. Middle panel: fundus autofluorescence imaging (FAF). Right panel: optical coherence tomography (OCT). F12: papillomacular fold with diffuse white dots in the posterior pole and to a lesser extent throughout retina, increased autofluorescence at sites of white dots, thickened OCT with occasional intraretinal cyst. F14: papillomacular fold, large posterior pole white dots that have increased autofluorescence, thickened OCT. F19: color fundoscopy showing crowded optic disc and prominent papillomacular fold, normal autofluorescence on FAF imaging, thickened OCT with foveal hypoplasia and papillomacular fold.

Discussion

This study characterizes 21 unrelated families with NNO (n = 6) or MCOP (n = 19). Fourteen distinct MFRP and PRSS56 variants were identified in the majority of the studied families (19/21, 90.5%). Eight different MFRP variants were found in 10/21 (47.6%) of the families, five of which are novel. Biallelic pathogenic variants were found in 9/10 families, supporting autosomal recessive inheritance. In line with the previously reported 19 distinct MFRP variants, mainly causing the introduction of a premature termination codon20,38–44, frameshift and nonsense variants represent the majority of the MFRP mutation spectrum of this study. Some of these variants were found to be recurrent: a novel mutation c.1090_1094del p.(Thr364Glnfs*26) in two unrelated Belgian families (F1 and F9) and a known mutation c.498del p.(Asn167Thrfs*25) in two Moroccan (F2, F10) and one Italian family (F8). The latter variant was previously reported amongst other consanguineous and non-consanguineous families of Spanish, Palestinian, Mexican and Japanese origin9,22,38,42,45,46. Interestingly, the previously reported reciprocal duplication c.498dup p.(Asn167Glnfs*34)8,43, which might point to a mutational hotspot, was found in a Dagestanian family (F5) in our cohort.

In one individual with MCOP (F4) a monoallelic MFRP variant was found c.491_492insT p.(Asn167Glnfs*34)43, with an as yet unidentified second mutation. A structural variant including a copy number variant (CNV), deep intronic mutation of regulatory mutation are possible underlying causes to be explored further. Indeed, this study provided evidence for the occurrence of CNVs affecting MFRP with the identification of the 6.2 kb deletion c.6087_54 +40delinsTAGTGGT.

To date, nine distinct PRSS56 pathogenic variants have been described, mostly frameshift and nonsense mutations17,24,47,48. In our cohort, we detected six different PRSS56 mutations in 9/21 (42.8%) families, some of which are known as recurrent mutations. Specifically, the previously reported missense variant c.1555G > A p.(Gly519Arg), which was found in a Saudi Arabian family41,48, was identified in four unrelated families of Pakistani origin in this study (F14, F15, F16 and F17), suggestive of a founder mutation in this population. Another recurrent mutation is c.1066dup p.(Gln356Profs*152) found in a Pakistani family (F12), which was previously reported in six Tunisian and five Saudi Arabian families17,48,49. Furthermore, two novel missense mutations were found in the PRSS56 group in patients with isolated MCOP (F13, F18) and NNO (F19).

Overall, isolated cases with NNO or MCOP were found in 13/19 (68.4%) of the families with a molecular diagnosis, mostly in the PRSS56-associated group (11/13, 84.6%). Complex cases with retinal involvement (RP features or ERG changes) were found in 6/19 (31.6%) of the families with a molecular diagnosis, mostly due to MFRP mutations (5/6, 83.3%). The retinal involvement in the MFRP-associated group is in line with previous phenotypic studies39 and is in agreement with its expression pattern in human, mouse and zebrafish eyes including neural and pigmentary retina3,20,21 and its role in photoreceptor outer segment maintenance50. An additional explanation could be the fact that MFRP and a gene implicated in late-onset retinal dystrophy, C1QTNF5 (encoding C1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein 5) are both expressed as a bicistronic transcript and found to co-localize to the same tissues with a clear functional relationship in the retina51,52.

The presence of papillomacular folds was found to be more frequent in MCOP (12/19, 63.2%) than in NNO (3/6, 50%). It has been proposed that these papillomacular folds result from the disparity between the retinal and scleral growth which seems to be more prominent in MCOP cases, although no clear genotype-phenotype correlations have been established yet16,21,48.

Finally, no clear genotype-phenotype correlations could be established in our studied cohort. For instance in the MFRP group both F2 and F3, having a ‘null’ allele and a missense variant respectively, displayed posterior microphthalmos without RP-like changes. On the other hand, clinical heterogeneity was observed in the PRSS56 group, illustrated by a missense variant c.766T > C, p.(Cys256Arg) identified in F18 with a clinical diagnosis of MCOP and in F19 with a diagnosis of NNO.

Finally, a definite genetic diagnosis opens up opportunities for gene-based therapies in MFRP-associated retinal disease. Indeed, studies in two mouse models have demonstrated that MFRP-retinopathy is a potential target for gene-based therapy: Mfrprd6/Mfrprd6 described by Dinculescu et al.53 and Mfrp KI/KI described by Chekuri et al.54.

In conclusion, MFRP and PRSS56 pathogenic variants, including the first genomic rearrangement of MFRP, were found in the majority (19/21, 90.5%) of the studied families, displaying a large phenotypic variability. No mutations were found in two Belgian families with NNO, leaving the possibility to identify underlying mutations in other NNO genes, or to uncover (a) novel NNO gene(s). Overall, this study expands the phenotypic and molecular spectrum of MFRP- and PRSS56-associated autosomal recessive NNO and MCOP in the largest cohort reported to date.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was approved and funded by grants from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO, Brussels, Belgium) to E.D.B. and B.P.L. who are FWO Senior Clinical Investigators (1802220N and 1803816N), and King Saud University (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) to B.A. E.D.B. and B.P.L. are members of ERN-EYE. This study was supported by the Ghent University Special Research Fund (BOF15/GOA/011) to E.D.B., Hercules Foundation AUGE/13/023 to E.D.B., by Funds for Research in Ophthalmology (FRO) to B.A. NIHR-Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, Fight for Sight, RP Fighting Blindness, The Rosetrees Trust, Moorfields Special Trustees. G.A. is supported by a Fight for Sight Early Career Investigator award. The authors are very grateful to the families who participated in this study.

Author contributions

B.A. performed the genetic analyses, the experiments and data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. G.A. performed the genetic analyses, the experiments and data analysis, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. H.V. assisted with the data analysis, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. J.D.Z., I.B., I.C., T.D.R., S.H., M.S., A.D., M.P., D.W., J.R.A., A.R.W., B.P.L. and A.T.M. managed patients, provided and interpreted clinical data and critically reviewed the manuscript. E.D.B. conceptualized the study, supervised genetic analyses and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical input and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-57338-2.

References

- 1.Warburg M. Classification of microphthalmos and coloboma. Journal of medical genetics. 1993;30:664–669. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.8.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elder MJ. Aetiology of severe visual impairment and blindness in microphthalmos. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1994;78:332–334. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.5.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundin OH, et al. Developmental basis of nanophthalmos: MFRP Is required for both prenatal ocular growth and postnatal emmetropization. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008;29:1–9. doi: 10.1080/13816810701651241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kallen B, Tornqvist K. The epidemiology of anophthalmia and microphthalmia in Sweden. European journal of epidemiology. 2005;20:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s10654-004-6880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma AS, Fitzpatrick DR. Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2007;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auffarth GU, Blum M, Faller U, Tetz MR, Volcker HE. Relative anterior microphthalmos: morphometric analysis and its implications for cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1555–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu W, et al. Cataract surgery in patients with nanophthalmos: results and complications. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2004;30:584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala-Ramirez R, et al. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Molecular vision. 2006;12:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zenteno JC, Buentello-Volante B, Quiroz-Gonzalez MA, Quiroz-Reyes MA. Compound heterozygosity for a novel and a recurrent MFRP gene mutation in a family with the nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa complex. Molecular vision. 2009;15:1794–1798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonmez K, Ozcan PY. Angle-closure glaucoma in a patient with the nanophthalmos-ocular cystinosis-foveoschisis-pigmentary retinal dystrophy complex. BMC ophthalmology. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs J, et al. Hereditary high hypermetropia in the Faroe Islands. Ophthalmic genetics. 2005;26:9–15. doi: 10.1080/13816810590918406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross HE, Yoder F. Familial nanophthalmos. American journal of ophthalmology. 1976;81:300–306. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh MK, Goldberg MF. Abnormal foveal avascular zone in nanophthalmos. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007;143:1067–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarvananthan N, et al. The prevalence of nystagmus: the Leicestershire nystagmus survey. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2009;50:5201–5206. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zacharias LC, et al. Efficacy of topical dorzolamide therapy for cystoid macular edema in a patient with MFRP-related nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disk drusen syndrome. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2015;9:61–63. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano JC, Hodgkins PR, Taylor DS, Gole GA, Kriss A. The nanophthalmic macula. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1998;82:276–279. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gal A, et al. Autosomal-recessive posterior microphthalmos is caused by mutations in PRSS56, a gene encoding a trypsin-like serine protease. American journal of human genetics. 2011;88:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albar AA, Nowilaty SR, Ghazi NG. Posterior microphthalmos and papillomacular fold-associated cystic changes misdiagnosed as cystoid macular edema following cataract extraction. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.) 2015;9:73–76. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S75771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoh M. Molecular cloning and characterization of MFRP, a novel gene encoding a membrane-type Frizzled-related protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2001;282:116–123. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundin OH, et al. Extreme hyperopia is the result of null mutations in MFRP, which encodes a Frizzled-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9553–9558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501451102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collery RF, Volberding PJ, Bostrom JR, Link BA, Besharse JC. Loss of Zebrafish Mfrp Causes Nanophthalmia, Hyperopia, and Accumulation of Subretinal Macrophages. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57:6805–6814. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neri A, et al. Membrane frizzled-related protein gene-related ophthalmological syndrome: 30-month follow-up of a sporadic case and review of genotype-phenotype correlation in the literature. Molecular vision. 2012;18:2623–2632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soundararajan R, et al. Gene profiling of postnatal Mfrprd6 mutant eyes reveals differential accumulation of Prss56, visual cycle and phototransduction mRNAs. PloS one. 2014;9:e110299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair KS, et al. Alteration of the serine protease PRSS56 causes angle-closure glaucoma in mice and posterior microphthalmia in humans and mice. Nature genetics. 2011;43:579–584. doi: 10.1038/ng.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiefer AK, et al. Genome-wide analysis points to roles for extracellular matrix remodeling, the visual cycle, and neuronal development in myopia. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verhoeven VJ, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of multiancestry cohorts identify multiple new susceptibility loci for refractive error and myopia. Nature genetics. 2013;45:314–318. doi: 10.1038/ng.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCulloch DL, et al. ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update) Documenta ophthalmologica. Advances in ophthalmology. 2015;130:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10633-014-9473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sante T, et al. ViVar: a comprehensive platform for the analysis and visualization of structural genomic variation. PloS one. 2014;9:e113800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coppieters F, et al. Massively parallel sequencing for early molecular diagnosis in Leber congenital amaurosis. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2012;14:576–585. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raczy C, et al. Isaac: ultra-fast whole-genome secondary analysis on Illumina sequencing platforms. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013;29:2041–2043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carss KJ, et al. Comprehensive Rare Variant Analysis via Whole-Genome Sequencing to Determine the Molecular Pathology of Inherited Retinal Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hull S, et al. Nonsyndromic Retinal Dystrophy due to Bi-Allelic Mutations in the Ciliary Transport Gene IFT140. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1053–1062. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vissers LE, et al. Rare pathogenic microdeletions and tandem duplications are microhomology-mediated and stimulated by local genomic architecture. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3579–3593. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verdin H, et al. Microhomology-mediated mechanisms underlie non-recurrent disease-causing microdeletions of the FOXL2 gene or its regulatory domain. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang F, Gu W, Hurles ME, Lupski JR. Copy number variation in human health, disease, and evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:451–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crespi J, et al. A novel mutation confirms MFRP as the gene causing the syndrome of nanophthalmos-renititis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disk drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukhopadhyay R, et al. A detailed phenotypic assessment of individuals affected by MFRP-related oculopathy. Mol Vis. 2010;16:540–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pehere N, Jalali S, Deshmukh H, Kannabiran C. Posterior microphthalmos pigmentary retinopathy syndrome. Doc Ophthalmol. 2011;122:127–132. doi: 10.1007/s10633-011-9266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aldahmesh MA, et al. Posterior microphthalmos as a genetically heterogeneous condition that can be allelic to nanophthalmos. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:805–807. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsushita I, Kondo H, Tawara A. Novel compound heterozygous mutations in the MFRP gene in a Japanese patient with posterior microphthalmos. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s10384-012-0145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wasmann RA, et al. Novel membrane frizzled-related protein gene mutation as cause of posterior microphthalmia resulting in high hyperopia with macular folds. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:276–281. doi: 10.1111/aos.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y, et al. Identification of MFRP Mutations in Chinese Families with High Hyperopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:19–26. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beryozkin A, et al. Identification of mutations causing inherited retinal degenerations in the israeli and palestinian populations using homozygosity mapping. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1149–1160. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson R, Tracey-White D, Webster A, Moosajee M. The zebrafish eye-a paradigm for investigating human ocular genetics. Eye (Lond) 2017;31:68–86. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orr A, et al. Mutations in a novel serine protease PRSS56 in families with nanophthalmos. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1850–1861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowilaty SR, et al. Biometric and molecular characterization of clinically diagnosed posterior microphthalmos. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:361–372 e367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang D, et al. Evaluation of PRSS56 in Chinese subjects with high hyperopia or primary angle-closure glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2013;19:2217–2226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Won J, et al. Membrane frizzled-related protein is necessary for the normal development and maintenance of photoreceptor outer segments. Vis Neurosci. 2008;25:563–574. doi: 10.1017/S0952523808080723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mandal MN, et al. Spatial and temporal expression of MFRP and its interaction with CTRP5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5514–5521. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fogerty J, Besharse JC. 174delG mutation in mouse MFRP causes photoreceptor degeneration and RPE atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7256–7266. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dinculescu A, et al. Gene therapy for retinitis pigmentosa caused by MFRP mutations: human phenotype and preliminary proof of concept. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:367–376. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chekuri A, et al. Long-Term Effects of Gene Therapy in a Novel Mouse Model of Human MFRP-Associated Retinopathy. Hum Gene Ther. 2019;30:632–650. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.