Abstract

Rivers are a major supplier of particulate and dissolved material to the ocean, but their role as sources of bio-essential dissolved iron (dFe) is thought to be limited due to rapid, efficient Fe removal during estuarine mixing. Here, we use trace element and radium isotope data to show that the influence of the Congo River margin on surface Fe concentrations is evident over 1000 km from the Congo outflow. Due to an unusual combination of high Fe input into the Congo-shelf-zone and rapid lateral transport, the Congo plume constitutes an exceptionally large offshore dFe flux of 6.8 ± 2.3 × 108 mol year−1. This corresponds to 40 ± 15% of atmospheric dFe input into the South Atlantic Ocean and makes a higher contribution to offshore Fe availability than any other river globally. The Congo River therefore contributes significantly to relieving Fe limitation of phytoplankton growth across much of the South Atlantic.

Subject terms: Element cycles, Ocean sciences

The influence of the Congo River margin on surface Fe concentrations is understudied. Here the authors show that such influence is evident over 1000 km from the Congo outflow.

Introduction

Elevated dissolved trace element (dTE; defined by <0.2 µm filtration) concentrations in coastal regions are derived from riverine inputs1,2, benthic pore-water and resuspended sediment supply3, atmospheric deposition4, and submarine groundwater discharge (SGD)5. Whilst riverine fluxes of dTEs into the ocean are significant, estuarine processes remove a high, but variable, fraction of riverine dissolved Fe (dFe). Typically 90–99% of dFe is removed at low salinity in estuaries due to the rapid aggregation of Fe and organic species with increasing ionic strength6, with further removal by biological uptake and scavenging in estuarine and shelf regions7. Whilst riverine Fe concentrations are 3–5 orders of magnitude greater than those in seawater8, rivers provide only ~3% (after estuarine removal) of the new Fe delivered annually to the oceans9. Consequently, there is typically limited potential for river-derived Fe to directly affect productivity in offshore ocean regions where Fe often limits, or co-limits, primary production10.

The Congo is the second largest river on Earth by discharge volume11, and is the only major river to discharge into an eastern boundary ocean region with a narrow shelf12—unique characteristics for a near-equatorial river plume subject to low Coriolis forces11. Although the Congo is a large source of freshwater to the SE Atlantic13, little is known about associated TE fluxes and their influence on SE Atlantic productivity. In November–December 2015, the GEOTRACES cruise GA08 proceeded along the SW African shelf to determine the lateral extent of chemical enrichment from the Congo plume. Here we use a conservative terrigenous tracer, naturally occurring radium isotopes (228Ra and 224Ra), in combination with TE distributions to derive TE fluxes from the Congo plume into the South Atlantic. Radium isotopes are produced by sedimentary thorium decay, released from river plumes and shelf sediments, and then transported to the open ocean by turbulent mixing and advection14,16. In seawater, only mixing and decay processes control Ra distribution.

Here we show that the dFe removal occurring within the Congo estuary is balanced by other dFe inputs into the shelf region near the Congo River outflow (Congo-shelf-zone; Fig. 1). River input of dissolved and desorbed particulate Ra cannot maintain the Ra inventory observed in the Congo-shelf-zone. There must be a significant Ra and TE source between the river and the Congo-shelf-zone, likely shelf sediments and/or SGD. These inputs, combined with strong lateral advection, sustain a pronounced plume of dTEs evident in an off-shelf transect at 3°S. The presence of TEs and 228Ra, and their strong inverse correlation with salinity in surface waters several hundreds of kilometers off-shelf indicates rapid horizontal mixing of the river plume. This facilitates the delivery of high levels of TEs from the Congo River outflow into the Southeast Atlantic Ocean, a reportedly oligotrophic region10.

Fig. 1. Map of the study region showing station locations along the GEOTRACES GA08 cruise transect.

Ship underway salinity measurements along the cruise section (a). Insets provide a detailed view of the study region including bathymetry and 228Ra stations sampled in the Congo-shelf-zone (b; stations 1202, 1206, and 1210), along the coastal transect (between stations 1210 and 1218), and along the offshore 3°S transect (c; stations 1218–1247). Satellite-derived surface seawater salinity during GEOTRACES cruise GA08 is provided in the Supplementary Information. Bathymetry and shoreline data were obtained from ref. 65 and ref. 66.

Results and Discussion

Trace element and radium distributions

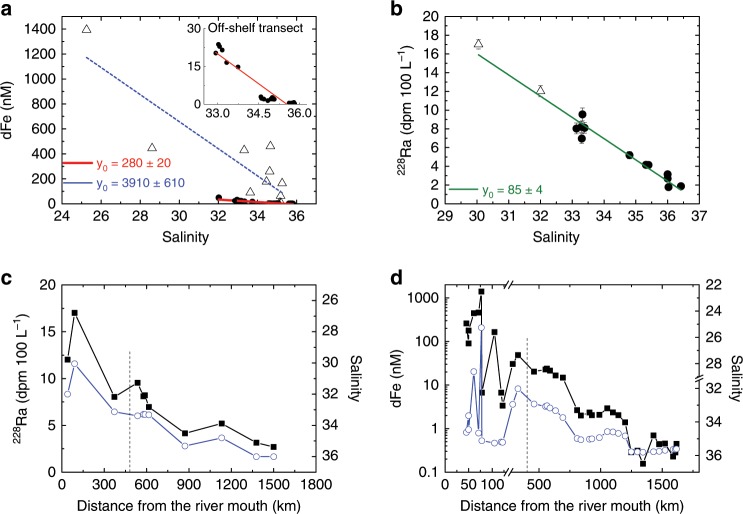

On the shelf where Congo waters first encounter the Atlantic Ocean, hereafter the Congo-shelf-zone (Fig. 1), the mean dFe concentration was ~15% of the Congo River concentration, indicating low apparent dFe removal compared with Congo River freshwater. About 50–85% of river-derived dFe is reportedly removed from solution at low salinities (0–5) in the Congo estuary, with the greatest removal in large size fractions2. Mean (± standard deviation) dFe concentration in the Congo River freshwater (measured in April, July, and October 2017) was 7380 ± 3150 nM, similar to limited previous measurements (~9000 nM)2. Extrapolating the linear regression line of dFe vs. salinity in the Congo-shelf-zone (Fig. 2a) to zero salinity provides an effective-zero-salinity-endmember concentration of 3910 ± 610 nM (R2 = 0.76), indicating that only ~50% of dFe is removed during estuarine mixing processes. This is consistent with prior work2, but notably limited compared with other river systems where 90–99% is typically stripped from the water column2,6. Slow removal of Fe in some estuaries17 has been attributed to stabilization by organic ligands, making the dFe pool resistant to flocculation18. Alternatively, sources of Fe other than river water may simply offset the loss from estuarine mixing. Indeed, similar 228Ra and other TE enrichments over the Congo-shelf-zone (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 1) suggest they have a common source, likely shelf sediments3,19 or SGD5. This indicates that the apparently low removal primarily reflects additional sources of dFe rather than unusually pronounced stabilization of the river-derived dFe. Strong benthic Fe input in this region is consistent with observed high rates of sediment accumulation and high rates of iron solubilization from the shelf break down to deep-sea fan sediments20,21, which may also contribute to the relatively high dFe concentrations in the Congo-shelf-zone.

Fig. 2. Distributions of dFe, Ra and salinity in surface waters.

Mixing diagram between river and open ocean waters from the Congo-shelf-zone to the end of the 3°S transect (stations 1202-1247) for dFe (a) and 228Ra concentrations (b). Open triangles represent the samples collected in the Congo-shelf-zone and circles represent the samples in the off-shelf 3°S transect. Dashed blue line in a represents the regression line for the Congo-shelf-zone, and the red line represents linear regression for the off-shelf transect. Intercepts are represented as y0 and considered as the effective-zero-salinity-endmembers. Inset in a is an expanded version of the off-shelf transect. The regression line for 228Ra (green line in b) includes all data. c, d 228Ra, dFe (note log scale) (solid squares), and inverse salinity distributions (open circles) in plume surface waters from the Congo-shelf-zone to the end of the 3°S transect (stations 1202-1247). Dashed vertical lines in c and d represent the beginning of the off-shelf transect at 3°S. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Covariations of dissolved manganese (dMn) and cobalt (dCo) with salinity indicate an effective-zero-salinity-endmember higher than dMn and dCo concentrations measured in the river (Table 1). This is also indicative of nonconservative dTE inputs into the Congo-shelf-zone relative to simple mixing of river and seawater (Supplementary Fig. 1). An additional TE source in the Congo-shelf-zone is also evident in the lower Fe/Mn (6.3 ± 6.0) and Fe/Co (525 ± 490) ratios compared with the Congo River (Fe/Mn = 71.2 ± 37.5; Fe/Co = 4.29 ± 2.34). These ratios reflect how dFe is removed relative to the other elements, which is unclear from the available gross fluxes alone. These ratios suggest that Congo River dFe is removed by a factor of 10, whereas the fluxes (Table 1, discussed below) indicate that the removal is only a factor of 2. In summary, a multielement approach also corroborates significant dTE inputs into the Congo-shelf-zone other than Congo River water.

Table 1.

Radium-228 and trace element fluxes.

| Congo Rivera | Congo-shelf-zoneb | Off-shelf 3°S transectb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 228Ra Flux (atoms year−1) | 4.8 ± 0.4 × 1021 | 3.4 ± 0.9 × 1021 | 6.2 ± 2.0 × 1021 |

| dFe-Flux (mol year−1) | 9.6 ± 4.1 × 109 | 5.6 ± 4.6 × 109 | 6.8 ± 2.3 × 108 |

| dMn-Flux (mol year−1) | 1.3 ± 0.4 × 108 | 4.4 ± 1.8 × 108 | 3.1 ± 1.2 × 108 |

| dCo-Flux (mol year−1) | 2.2 ± 0.8 × 106 | 5.3 ± 2.0 × 106 | 4.6 ± 1.8 × 106 |

| dFe/228Ra gradient (pmol atoms−1) | – | 1.66 ± 1.3 | 0.1 ± 0.02 |

| dMn/228Ra gradient (pmol atoms−1) | – | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| dCo/228Ra gradient (fmol atoms−1) | – | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Average 228Ra activity (dpm 100 L−1) | – | 12.7 ± 3.6 | 8.62 ± 0.86 |

| Average dFe concentration (nM) | 7380 ± 3150 | 920 ± 670 | 20.9 ± 1.67 |

| Average dMn concentration (nM) | 105 ± 30 | 73 ± 4.0 | 14.7 ± 4.48 |

| Average dCo concentration (nM) | 1.72 ± 0.59 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

aTrace element (TE) fluxes from the Congo River were determined using the measured TE concentrations in the Congo River (Supplementary Table 1) and river discharge reported in ref. 30. Radium-228 flux from the Congo River was estimated by extrapolating the regression line to zero salinity (Fig. 2b) and multiplying the intercept by the river discharge

bSee “Methods” for details on TE and 228Ra concentrations and fluxes in the Congo-shelf-zone and off-shelf transect

Elevated 228Ra and TEs in the Congo River plume can be traced off-shelf at 3°S over 1000 km from the Congo River mouth (Fig. 2c). Benthic input supplies 228Ra and TEs between the river mouth and the Congo-shelf-zone (here considered as the 10,000 km2 plume area; “Methods”), but conservative 228Ra mixing behavior (Fig. 2b) then indicates no additional 228Ra inputs beyond the Congo-shelf-zone. The similarity between the 228Ra and TE distributions with salinity (Fig. 2c, d; Supplementary Fig. 1) indicates that the plume forms the only major source of Ra and TEs in this region. Salinity increased offshore along the 3°S transect, with occasional fresher pockets coincident with elevated 228Ra and TE concentrations (e.g., at 1100 km; Fig. 2c, d). These likely result from transport by filaments, meanders, or eddies originating near the Congo River mouth22,23. The linear 228Ra gradient with distance beyond 360 km offshore (R2 = 0.91) (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicates that the 228Ra distribution is controlled by eddy diffusion near the shelf break24 (Supplementary Note 1). The slope of 228Ra vs. distance changes beyond the shelf break, likely due to offshore advection.

The effective-zero-salinity-endmember concentration calculated for dFe was 90% lower for the off-shelf samples compared with the Congo-shelf-zone samples (280 nM vs. 3910 nM; Fig. 2a), indicating substantial removal of dFe along the flow path of the Congo plume within 400 km of the river mouth. Despite this removal, elevated dFe was still observed at the start of the off-shelf transect, up to 600 km from the river mouth (~25 nM; Fig. 3). dFe concentrations in other shelf systems typically decline sharply at the shelf break to less than 1 nM25,26 and thus the influence of major rivers (e.g., the Amazon River) on surface ocean Fe concentrations is more limited27. dFe concentrations of ~15 nM were observed 100 km beyond the shelf break, and remained >2 nM for 500 km beyond the shelf break. These features indicate a sustained Fe flux into the South Atlantic Gyre where Fe limitation or co-limitation of primary production has been observed10.

Fig. 3. Comparison of dFe concentrations vs. distance from the river mouth in other riverine systems globally.

The presence of dFe several hundreds of kilometer off-shelf indicates more rapid horizontal mixing of Congo River plume compared with other systems1,5,27,54,67–69. TPD indicates transpolar drift, and NY Bight indicates New York Bight. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Radium and trace element fluxes in the Congo-shelf-zone

Ra isotopes were used to quantify TE fluxes for the Congo-shelf-zone, where additional TE and Ra inputs created an intermediate endmember that mixed approximately conservatively along the Congo plume (Fig. 2a, b); and also for the 3°S off-shelf transect, where there was no additional Ra input.

The highest 228Ra concentration (224Ra = 8.15 dpm 100 L−1; 228Ra = 17.2 dpm 100 L−1) was found at the lowest observed salinity (S = 30; 100 km from river mouth; Fig. 2b). At salinity 30, all surface-associated Ra from river particles is desorbed16,28,29 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The 228Ra Congo-shelf-endmember (“Methods”) therefore includes all dissolved 228Ra derived from desorption from river-borne particles, the river dissolved phase, and shelf sediments near the river mouth. The water residence time in the Congo-shelf-zone is ~3 days13,30. Assuming steady state and negligible loss by decay, the residence time and 228Ra inventory in the Congo-shelf-zone (“Methods”), indicate a 228Ra flux into this region of 3.4 ± 0.9 × 1011 atoms m−2 year−1, or ~3.4 ± 0.9 × 1021 atoms year−1 when scaled to a plume area of 10,000 km2.

Conservative mixing between the Congo-shelf-endmember and offshore waters (Fig. 2b) indicates a riverine 228Ra effective-zero-salinity-endmember concentration of 85 ± 4 dpm 100 L−1, including both dissolved and desorbed Ra. Together with the river discharge (1.3 × 1012 m3 year−1)31, this suggests a fluvial 228Ra flux of 4.8 ± 0.4 × 1021 atoms year−1, which is similar to the 228Ra flux estimated for the Congo-shelf-zone (3.4 ± 0.9 × 1021 atoms year−1). If the assumption of conservative mixing behavior is correct, the effective-zero-salinity-endmember would be similar to actual river Ra concentrations, which are not known.

Radium-228 data are not available for the Congo River, but global rivers are generally less than 20 dpm 100 L−132 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Assuming the Congo is similar to other major rivers (~20 dpm 100 L−1), the average Congo River discharge31 would supply 2.6 × 1014 dpm year−1, or ~10 × 1020 atoms year−1 of dissolved 228Ra. Desorption of surface-bound Ra from river-borne particles generally supplies <2 dpm g−115. The Congo suspended sediment load is 43 Mt year−131, so desorption can supply no more than ~3.75 × 1020 atoms year−1, or an equivalent dissolved 228Ra activity of 6 dpm 100 L−1. Thus, the total supply of 228Ra from the Congo River itself is estimated to be ~1.4 × 1021 atoms year−1, or only ~30–35% of the determined flux into the Congo-shelf-zone. If the remainder was supplied by benthic diffusion, it would represent a flux on the order of 400 × 109 atoms m−2 year−1, nearly fourfold higher than the maximum reported globally33. This suggests that either the dissolved 228Ra concentration in the Congo River is exceptionally high compared with other large rivers (~79 dpm 100 L−1 vs. <20 dpm 100 L−1 elsewhere); or 228Ra diffusion from shelf sediments in this region is anomalously high compared with other regions globally; or there is another source of Ra such as SGD34,35. Based on observations elsewhere of large variability of 228Ra diffusion from shelf sediments36 and SGD input14, the second and third hypothesis, or a combination of both, are most likely.

Radium-228 and TEs have a common source in the estuarine mixing zone up to our Congo-shelf-endmember, and combining the 228Ra flux and concentration ratios of TE/228Ra (“Methods”) for the Congo-shelf-zone provides a dFe-flux (dFe-FluxCongo-shelf) of 5.6 ± 4.6 × 105 µmol m−2 year−1 (5.6 ± 4.6 × 109 mol year−1), an order of magnitude higher than reported along other continental margins37,38. The corresponding dMn-FluxCongo-shelf was 4.4 ± 1.8 × 108 mol year−1; and dCo-FluxCongo-shelf was 5.3 ± 2.0 × 106 mol year−1 (Table 1). The large 228Ra and TE fluxes determined here are derived from their inventories in the Congo-shelf-zone, and this does not take into account seasonal variations in their supply to surface waters. Sample collection at sea occurred during the high discharge season of the Congo River. Seasonal variations of the river flow (mean annual range between 35 and 60 × 103 m3 s−139 with approximately a twofold seasonal variation in dFe concentrations (Supplementary Table 1) can strongly affect the Congo River plume dispersion40, and potentially the delivery of river-derived materials to the SE Atlantic Ocean. The corresponding seasonal variation in benthic supply of 228Ra and TEs to overlying plume waters on the Congo shelf is also unconstrained.

Radium and trace element off-shelf fluxes at 3°S

The shelf width at 3°S is 70 km, giving an offshore 228Ra inventory within the plume cross section of 2.6 ± 0.2 × 1013 atoms m−2. With a residence time of 7 ± 2 days (“Methods”), a 228Ra input from the Congo plume into the open Atlantic Ocean is 1.4 ± 0.4 × 1015 atoms m−2 year−1, or assuming a plume thickness of 15 m (Supplementary Fig. 4), 22 ± 6.2 × 1015 atom year−1 m-shoreline−1. Satellite-derived surface salinity at 3°S (Supplementary Fig. 5) indicates a shoreline plume width of ~300 km, so the total offshore 228Ra flux is 6.2 ± 2.0 × 1021 atoms year−1. Within uncertainties, this flux matches that estimated for the Congo-shelf-zone (3.4 ± 0.9 × 1021 atoms year−1), consistent with the observed conservative mixing behavior of 228Ra in the plume. The flux represents 4% of previous estimates of total annual 228Ra input into the Atlantic Ocean33.

Tracer derived flux calculations in dynamic cross-shelf regions are complicated by meso-scale features like eddies23, which may influence TE and Ra distributions. Nevertheless, our data unambiguously indicate that the Congo plume is a dominant regional source of Fe, Mn, and Co to the South Atlantic Gyre. Similarity between the TE and 228Ra distributions suggests that the fluxes scale proportionally38. Given a Fe/228Ra ratio of 0.1 pmol atom−1, the off-shelf dFe-Flux from the Congo River plume into the South Atlantic Ocean is 6.8 ± 2.3 × 108 mol year−1 (or 138 ± 51 mol m−2 year−1). On a global scale, this represents 0.7–2.3% of the global sedimentary Fe flux (2.7–8.9 × 1010 mol year−1)3,41, or ~40 ± 15% (based on the uncertainties of our estimate) of total dFe atmospheric deposition into the entire South Atlantic Ocean42. The similarity between dMn and dCo fluxes in the Congo-shelf-zone and off-shelf transect (Table 1) is consistent with their conservative behavior along the Congo River plume, likely because of slow Mn and Co oxidation43,44 and Mn photo reduction in surface waters45, which keeps Mn in solution and facilitates its off-shelf transport. Our total off-shelf TE fluxes are similar to those reported elsewhere for other ocean margin regions37,38, although in the current study this flux occurs over a much smaller area.

Atmospheric deposition is thought to be an important source of dFe to the surface ocean, and the West African margin receives dust fluxes which are amongst the highest in the world46. So how does atmospheric deposition compare to lateral dFe supply from the Congo across this region? Dissolved Al is a useful tracer of recent dust deposition to the surface ocean, and atmospheric deposition has been estimated from GA08 Al data47 as 2.65 g m−2 year−1 for the offshore (3°S) section and 2.67 g m−2 year−1 for the coastal transect. The offshore values exclude stations within the coastal shelf zone where other dAl sources, certainly including a contribution from direct Congo River discharge, preclude the use of this tracer. Nevertheless, if all dAl within the study region were attributed to atmospheric deposition it would correspond to deposition of 26.2 g m−2 year−147. The fractional composition and solubility of Fe in dust vary widely. Using a broad range of plausible dust Fe content (1.9–5.0%) and Fe solubility (0.14–21%)48,49 suggests that Fe deposition in these regions is within the range of 13–4900 µmol m−2 year−1 (a minimum and maximum limit given the contribution of dAl from nonatmospheric sources in this zone), or 0.01–4.93 × 107 mol year−1, 1–3 orders of magnitude lower than our estimated dFe fluxes from the Congo-shelf-zone to the same region (Table 1).

Whilst considerable in a global context, these estimates of atmospheric deposition therefore represent only a small fraction (<1%) of the TE fluxes into the Congo-shelf-zone. Combined with the strong correlation between TE concentrations, 228Ra concentrations and salinity, this strongly suggests that outflow from the Congo-shelf-zone dominates TE supply across this region, with atmospheric deposition only a minor contributing factor.

As the Congo is the dominant river in the region (approximately four times larger than other more northerly rivers combined31), we consider that the contribution of other rivers to the low salinity plume observed in the study region is minimal. The enhanced dFe-flux from the Congo, relative to other rivers (see Fig. 3), into the South Atlantic may partially result from stabilization by organic ligands50. However, elevated dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations are common in many major river systems51,52, and dFe removal in the Congo estuary has been explicitly demonstrated2. Therefore high DOC alone cannot explain the unique dFe distribution observed along the Congo plume. Similarly, near-conservative behavior of Fe has been found in some estuaries with rapid flushing53. Indeed, rapid lateral advection appears to enhance TE transport from the Congo compared with other rivers (Fig. 3). A similar feature has been reported in the Arctic Ocean, where rapid transport of river-derived organic carbon and TEs through the Transpolar Drift leads to nanomolar TE concentrations in the central Arctic Ocean54.

The elevated dFe export observed here appears to impact phytoplankton in the South Atlantic Gyre. Primary production across extensive regions of the SE Atlantic is proximally limited, or co-limited by availability of the micronutrients Fe and Co due to limited atmospheric supply beyond the equatorial dust belt10. However, primary productivity within the offshore region in the current study was instead found to be limited by nitrogen availability10, likely due to the large TE input from the Congo plume. Changes to the spatial orientation of the plume due to shifts in wind patterns or changing freshwater discharge may therefore directly affect TE supply and thus offshore primary production within the South Atlantic Gyre. Wind speeds are likely to decrease in the Congo region over the coming century55 and a future reduction in Atlantic thermohaline circulation is projected to further alter prevailing wind patterns in the intertropical convergence zone56,57. On a decadal timescale, total annual rainfall across the Congo River Basin is not expected to change significantly, but an amplification of the seasonal variability of Congo River runoff is predicted58. There is therefore clear potential for consequences of climate change in the Congo region to affect nutrient availability and marine primary production in the SE Atlantic Ocean.

Methods

Sample collection and analysis

Surface seawater samples (3 m depth) for Ra isotopes and dFe analyses were collected onboard R/V Meteor during the GEOTRACES GA08 cruise in the Southern Atlantic between November 22 and December 27, 2015 (Fig. 1).

Radium isotopes

Surface samples (3 m depth) were collected by pumping ca. 250 L of seawater into a barrel. Seawater was then filtered through MnO2-impregnated acrylic fiber (Mn-fibers) at a flow rate <1 L min−1 to quantitatively extract Ra isotopes. After collection, the Mn-fibers were rinsed and air dried. Concentrations of 224Ra were determined using four Ra delayed coincidence counters (RaDeCC)59. The fibers were counted onboard and aged for 6 weeks, in order to allow excess 224Ra to completely decay. They were then recounted to determine 228Th concentrations and thus correct the total 224Ra for the supported activity. RaDeCC counters were calibrated with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reference solutions60.

After measurement of 224Ra, fibers were ashed and subsequently leached in order to determine the activity of long-lived Ra (228Ra and 226Ra) isotopes using a high-purity, well-type germanium (HPGe) gamma spectrometer. As the remaining amount of ash obtained was too large to fit inside the well of the HPGe detector (Canberra Eurisys GMBH, EGPC 150), the ashes were subsequently leached followed by coprecipitation with BaSO4. Ashing the fibers before leaching produced a more homogeneous material that was easier to handle as has been demonstrated occasionally elsewhere61. The fibers were ashed at 600 °C for 20 h, then leached in 6 M HCl followed by coprecipitation with BaSO4. The precipitate was then sealed in 1 mL vials and analyzed after at least 3 weeks to allow 222Rn to reach equilibrium with its parent 226Ra. Radium-226 concentrations were determined using the 214Pb peak (352 keV) and the 214Bi peak (609 keV), and 228Ra concentrations were determined using the 228Ac peaks (338 and 911 keV). Sample counting efficiencies were determined by spiking Mn-fibers with known amounts of 228Ra and 226Ra, and processing similar to samples. Sample activities were corrected for detector background counts and fiber blank activities. The radium calibration solution was provided by the IAEA, and had a reported activity accuracy of 6% for 226Ra and 5% for 228Ra. Measured precisions for 228Ra and 226Ra were ~5% (1–σ). These levels of accuracy and precision led to an uncertainty on the sample concentrations of <10%.

Trace elements

Surface trace element sampling was conducted using a tow fish deployed alongside the ship at about 3–4 m depth. Seawater was collected in a shipboard clean laboratory container and stored in acid-cleaned low density polyethylene 125 mL bottles. Samples for dTEs were collected using a cartridge filter (0.8/0.2 µm, Acropak 500 – PALL). All seawater samples were acidified onboard with ultra clean HCl (UpA grade, Romil) to pH 1.9. Freshwater Congo River samples were collected at three timepoints (April, July, and October 2017), retained for analysis of dFe after syringe filtration (0.20 µm, Millipore), and acidified as per seawater. Samples with concentrations below 20 nM dFe or dMn were measured following ref. 62. Samples with higher concentrations were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry after dilution with ultra-pure 1 M HNO3 (Romil SpA grade, sub-boiled), and calibration by standard addition. The accuracy and precision of measurements were evaluated by analysis of SAFe S, SAFe D2, and CASS6 reference seawater (Supplementary Table 2).

Radium-228 inventory and trace element flux estimates

The 228Ra Congo-shelf-endmember was determined by the average 228Ra concentrations (14.5 ± 3.5 dpm 100 L−1; Table 1) of samples with salinity less than 32 psu, which best reflect river influenced waters in the Congo-shelf-zone. This excess 228Ra was then corrected for the average offshore 228Ra concentration (1.8 ± 0.5 dpm 100 L−1)63, in order to account for mixing with offshore waters containing a background concentration of 228Ra. The 228Ra Congo-shelf-endmember is therefore 12.7 ± 3.6 dpm 100 L−1. We estimated the 228Ra inventory (I228) in the surface water of our Congo-shelf-endmember as 2.8 ± 0.8 × 109 atoms m−2 by considering a plume thickness of 5 m in the Congo-shelf-zone (Supplementary Fig. 4) and assuming a uniform 228Ra distribution within this plume thickness. Radium-228 flux from the Congo-shelf-zone was determined using the 228Ra inventory of our Congo-shelf-endmember and the residence time of water in the Congo-shelf-zone (Flux 228Ra = inventory/residence time). A residence time of 3 days13 is consistent with the Congo discharge volume required to produce the observed salinity within the plume region30. As our Congo-shelf-endmember is ~100 km away from the river mouth, the area of our sampling region was considered as a square of 100 × 100 km (whenever referring to the Congo-shelf-zone). Taking the 228Ra at the lowest measured salinities (S < 32) as representative of the entire Congo River mouth zone likely produces a lower estimate of the true inventory because concentrations are likely higher at mid-salinities nearer to the river mouth and shoreline (Supplementary Fig. 3). Note that the regional satellite-derived salinity shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 corresponds only qualitatively with measured salinity for the Ra samples in the Congo-shelf-zone (~30 psu). Radium-228 flux from the Congo River was estimated by extrapolating the regression line to zero salinity (Fig. 2b) and multiplying the intercept by river discharge. These two approaches were used to check if the Congo River flux and the 228Ra flux estimated for the Congo-shelf-zone were comparable, and thus to investigate to what extent the River flux on its own could explain 228Ra concentrations on the shelf.

Because dFe, dMn, and dCo in our study appear to have a source similar to Ra, the 228Ra flux was used to determine the fluxes of these TEs in the Congo-shelf-zone, by multiplying the 228Ra flux in this region by the average ratio of dTE concentrations (Table 1) observed in samples with the lowest measured salinity (i.e., <29 psu; TE Congo-shelf-endmember) and the 228Ra concentration of the Congo-shelf-endmember (dTE/228Ra). Samples with salinity < 29 represent intermediate TE endmembers that reflect mixing between the river and seawater (S > 33 psu). Ra and TE sampling locations do not coincide exactly, as unlike Ra samples, TE samples were collected as small volumes (125 mL) from a tow fish while the research vessel was underway.

The residence time of 7 ± 2 days at the start of the off-shelf transect (3°S; between stations 1218 and 1229, at the shelf break) was determined using the 224Ra/228Ra ratios as per ref. 64. We used the 224Ra/228Ra ratio at station 1218 as our initial ratio. Radium-224 was detectable over the next 40 km at the next two stations along this transect (station 1229). Once Ra isotopes are released into the water column, their activities decrease with increasing distance from the source as a result of dilution and radioactive decay. Both isotopes are affected by dilution, but radioactive decay is negligible for 228Ra (half-life = 5.8 years) over short distances, so changes in the 224Ra/228Ra ratio reflect the time elapsed since the water was isolated from the source. Within the Congo plume, strong density stratification isolates the freshwater plume from bottom waters, so surface waters are unlikely to be affected by additional Ra input. Therefore, the residence time (T) can be derived as follows:

| 1 |

where (224Ra/228Ra)i is the initial ratio at station 1218, (224Ra/228Ra)o is the ratio observed away from the source (offshore) at station 1229, and λ224 is the decay constant of 224Ra.

Previous studies have combined the 228Ra flux with water column dTE to 228Ra ratios (TE/228Ra) in order to quantify shelf-ocean input rates37,38. We propose the use of this approach to estimate the fluxes of TEs (dFe, dMn, and dCo) from the Congo River plume to the Atlantic Ocean following ref. 38.

| 2 |

where dTEshelf and 228Rashelf are the average concentrations of the dTE and 228Ra in surface waters over the shelf (between station 1218 and station 1229), respectively; and dTEoff-shelf and 228Raoff-shelf are the dTE concentration and 228Ra concentrations in surface waters of the open ocean station (station 1234). Note that a diffusion-dominated system between the stations 1218 and 1234 was observed as indicated by a linear gradient in both dFe and 228Ra distributions. The dTE/Ra ratios are presented in Table 1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the captain and crew of the RV Meteor M121 cruise/GEOTRACES GA08 section and the chief scientist M. Frank for cruise support. We thank S. Koesling, P. Lodeiro, and C. Schlosser for their assistance in sample collection on the GA08 expedition and T. Browning for the assistance with satellite data. We thank Mr Bomba Sangolay from the National Institute of Fisheries Research (Instituto Nacional de Investigação Pesqueira, Luanda, Angola) for collection of samples in the Congo River. The PhD Fellowships to L. H. Vieira and S. Krisch were funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil (CNPq - grant number 239548/2013-2) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AC 217/1-1), respectively. The cruise was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Source data

Author contributions

E.P.A., J.S., and L.H.V. designed the GA08 study. L.H.V. carried out the sampling, analyzed the radium samples, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.J.B., M.J.H. and L.H.V. worked on subsequent drafts. S.K. and M.J.H. analyzed GA08 trace element samples. A.J.B. and M.J.H. contributed with interpretation of results. V.L. helped with Ra analysis by gamma spectrometry. All authors contributed to final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. Source data for dTEs and Ra isotopes are provided as a Source Data File.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jordon Beckler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-14255-2.

References

- 1.Buck KN, Lohan MC, Berger CJM, Bruland KW. Dissolved iron speciation in two distinct river plumes and an estuary: implications for riverine iron supply. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2007;52:843–855. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.2.0843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figuères G, Martin JM, Meybeck M. Iron behaviour in the Zaire estuary. Neth. J. Sea Res. 1978;12:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0077-7579(78)90035-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elrod VA, Berelson WM, Coale KH, Johnson KS. The flux of iron from continental shelf sediments: a missing source for global budgets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004;31:2–5. doi: 10.1029/2004GL020216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jickells T. Atmospheric inputs of metals and nutrients to the oceans: their magnitude and effects. Mar. Chem. 1995;48:199–214. doi: 10.1016/0304-4203(95)92784-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windom HerbertL, et al. Submarine groundwater discharge: a large, previously unrecognized source of dissolved iron to the South Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Chem. 2006;102:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2006.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle EA, Edmond JM, Sholkovitz ER. The mechanism of iron removal in estuaries. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1977;41:1313–1324. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(77)90075-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birchill AJ, et al. The eastern extent of seasonal iron limitation in the high latitude North Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37436-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaillardet, J., Viers, J. & Dupré, B. Trace elements in river waters. In: Surface and Groundwater Weathering and Soils (ed. Drever, J. I.) 225–272 (Elsevier-Pergamon, Oxford, 2013).

- 9.Raiswell, R. & Canfield, D. E. The iron biogeochemical cycle past and present (Geochemical Perspectives, 2012).

- 10.Browning TJ, et al. Nutrient co-limitation at the boundary of an oceanic gyre. Nature. 2017;551:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature24063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins J, et al. Detection and variability of the Congo River plume fromsatellite derived sea surface temperature, salinity, ocean colour and sea level. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013;139:365–385. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2013.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stramma L, England MH. On the water masses and mean circulation Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 1999;104:863–20,883. doi: 10.1029/1999JC900139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisma D, van Bennekom AJ. The Zaire river and estuary and the Zaire outflow in the Atlantic Ocean. Neth. J. Sea Res. 1978;12:255–272. doi: 10.1016/0077-7579(78)90030-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon Eun Young, Kim Guebuem, Primeau Francois, Moore Willard S., Cho Hyung‐Mi, DeVries Timothy, Sarmiento Jorge L., Charette Matthew A., Cho Yang‐Ki. Global estimate of submarine groundwater discharge based on an observationally constrained radium isotope model. Geophysical Research Letters. 2014;41(23):8438–8444. doi: 10.1002/2014GL061574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore WS, Shaw TJ. Fluxes and behavior of radium isotopes, barium, and uranium in seven Southeastern US rivers and estuaries. Mar. Chem. 2008;108:236–254. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2007.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Key RM, Stallard RF, Moore WS, Sarmiento JL. Distribution and flux of 226Ra and 228Ra in the Amazon River estuary. J. Geophys. Res. 1985;90:6995–7004. doi: 10.1029/JC090iC04p06995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell RT, Wilson-Finelli A. Importance of organic Fe complexing ligands in the Mississippi River plume. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2003;58:757–763. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7714(03)00182-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krachler R, Jirsa F, Ayromlou S. Factors influencing the dissolved iron input by river water to the open ocean. Biogeosciences. 2005;2:311–315. doi: 10.5194/bg-2-311-2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elderfield H, Hepworth A. Diagenesis, metals and pollution in estuaries. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1975;6:85–87. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(75)90149-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckler, J. S., Kiriazis, N., Rabouille, C., Stewart, F. J. & Taillefert, M. Importance of microbial iron reduction in deep sediments of river-dominated continental-margins. Mar. Chem. 178, 22–34 (2016).

- 21.Taillefert M, et al. Early diagenesis in the sediments of the Congo deep-sea fan dominated by massive terrigenous deposits: part II – iron–sulfur coupling. Deep. Res. Part II. 2017;142:151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vangriesheim A, et al. The influence of Congo River discharges in the surface and deep layers of the Gulf of Guinea. Deep. Res. Part II. 2009;56:2183–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palma ED, Matano RP. Journal of geophysical research: oceans an idealized study of near equatorial river plumes. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017;122:3599–3620. doi: 10.1002/2016JC012554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore WS. Determining coastal mixing rates using radium isotopes. Cont. Shelf Res. 2000;20:1993–2007. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4343(00)00054-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Luther GW. Spatial and temporal distribution of iron in the surface water of the northwestern Atlantic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996;60:2729–2741. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(96)00135-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rijkenberg, M. J. A. et al. Fluxes and distribution of dissolved iron in the eastern (sub-) tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles26, GB3004 (2012).

- 27.Rijkenberg MJA, et al. The distribution of dissolved iron in the West Atlantic Ocean. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsinger RJ, Moore WS. 226Ra and 228Ra in the mixing zones of the Pee Dee River-Winyah Bay, Yangtze River and Delaware Bay Estuaries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1984;18:601–613. doi: 10.1016/0272-7714(84)90033-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li YH, Mathieu G, Biscaye P, Simpson HJ. The flux of 226Ra from estuarine and continental shelf sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1977;37:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(77)90168-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowden, K. Physical factors: salinity, temperature, circulation and mixing processes. in: Chemistry and Biogeochemistry of Estuaries (eds. Olausson, E., Cato, I.) 38–68 (John Wiley and Sons, 1980).

- 31.Milliman, J. D. & Farnsworth, K. L. River Discharge to the Coastal Ocean: A Global Synthesis (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- 32.McKee, B. A. U- and Th-series nuclides in estuarine environments. In: Radioactivity in the Environment 13, U–Th Series Nuclides in Aquatic Systems (eds. S. Krishnaswami and J. Kirk Cochran) 193–225 (Elsevier, 2008).

- 33.Moore WS, Sarmiento JL, Key RM. Submarine groundwater discharge revealed by 228Ra distribution in the upper Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2008;1:309–311. doi: 10.1038/ngeo183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore WS. Using the radium quartet for evaluating groundwater input and water exchange in salt marshes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996;60:4645–4652. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00289-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodellas V, Garcia-Orellana J, Masqué P, Font-Muñoz JS. The influence of sediment sources on radium-derived estimates of submarine groundwater discharge. Mar. Chem. 2015;171:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2015.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vieira LH, et al. Benthic fluxes of trace metals in the Chukchi Sea and their transport into the Arctic Ocean. Mar. Chem. 2019;208:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2018.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanial V, et al. Radium-228 as a tracer of dissolved trace element inputs from the Peruvian continental margin. Mar. Chem. 2018;201:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2017.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charette MA, et al. Coastal ocean and shelf-sea biogeochemical cycling of trace elements and isotopes: lessons learned from GEOTRACES. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2016;374:1–19. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Materia S, Gualdi S, Navarra A, Terray L. The effect of Congo River freshwater discharge on eastern equatorial Atlantic climate variability. Clim. Dyn. 2012;39:2109–2125. doi: 10.1007/s00382-012-1514-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Signorini SR, Murtugudde RG, Mcclain CR, Christian PJR, Busalacchi AJ. Biological and physical signatures in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic. J. Geophys. Res. 1999;104:18367–18385. doi: 10.1029/1999JC900134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tagliabue, A., Aumont, O. & Bopp, L. The impact of different external sources of iron on the global carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 920–926 (2014).

- 42.Duce, R. A. & Tindale, N. W. Atmospheric transport of iron and its deposition in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 1715–1726 (1991).

- 43.Sunda WG, Huntsman SA. Effect of sunlight on redox cycles of manganese in the southwestern Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part A. 1988;35:1297–1317. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(88)90084-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moffett JW, Ho J. Oxidation of cobalt and manganese in seawater via a common microbially catalyzed pathway. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996;60:3415–3424. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(96)00176-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sunda WG, Huntsman SA, Harvey GR. Photoreduction of manganese oxides in seawater and its geochemical and biological implications. Nature. 1983;301:234–236. doi: 10.1038/301234a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jickells TD, et al. Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. Science. 2005;308:67–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1105959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barraqueta JLM, et al. Atmospheric deposition fluxes over the Atlantic Ocean: A GEOTRACES case study. Biogeosciences. 2019;16:1525–1542. doi: 10.5194/bg-16-1525-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paris, R., Desboeufs, K. V. & Journet, E. Variability of dust iron solubility in atmospheric waters: investigation of the role of oxalate organic complexation. Atmos. Environ. 45, 6510–6517 (2011).

- 49.Guieu, C., Loÿe-Pilot, M. D., Ridame, C. & Thomas, C. Chemical characterization of the Saharan dust end-member: some biogeochemical implications for the western Mediterranean Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 107, ACH 5-1-ACH 5-11 (2002).

- 50.Spencer RGM, et al. An initial investigation into the organic matter biogeochemistry of the Congo River. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2012;84:614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sholkovitz ER, Boyle EA, Price NB. The removal of dissolved humic acids and iron during estuarine mixing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1978;40:130–136. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(78)90082-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benner R, Opsahl S. Molecular indicators of the sources and transformations of dissolved organic matter in the Mississippi river plume. Org. Geochem. 2001;32:597–611. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00197-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayer LM. Retention of riverine iron in estuaries. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1982;46:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90055-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rijkenberg MJA, Slagter HA, Rutgers van der Loeff M, van Ooijen J, Gerringa LJA. Dissolved Fe in the deep and upper Arctic ocean with a focus on Fe limitation in the Nansen Basin. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018;5:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mcinnes KL, Erwin TA, Bathols JM. Global climate model projected changes in 10 m wind speed and direction due to anthropogenic climate change. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2011;12:325–333. doi: 10.1002/asl.341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang R, Delworth TL. Simulated tropical response to a substantial weakening of the Atlantic thermohaline circulation. J. Clim. 2005;18:1853–1860. doi: 10.1175/JCLI3460.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong, B.-W. & Sutton, R. T. Adjustment of the coupled ocean-atmosphere system to a sudden change in the Thermohaline Circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 18-1–18-4 (2002).

- 58.Hänsler, A., Saeed, F. & Jacob, D. Assessment of projected climate change signals over central Africa based on a multitude of global and regional climate projections. in: Climate Change Scenarios for the Congo Basin (eds. Hänsler A, Jacob, D., Kabat, P., Ludwig, F.) 1–15, (Climate Service Centre Report No. 11, 2013).

- 59.Moore WS, Arnold R. Measurement of 223Ra and 224Ra in coastal waters using a delayed coincidence counter. J. Geophys. Res. 1996;101:1321–1329. doi: 10.1029/95JC03139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scholten JC, et al. Preparation of Mn-fiber standards for the efficiency calibration of the delayed coincidence counting system (RaDeCC) Mar. Chem. 2010;121:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2010.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsieh YTe, Henderson GM. Precise measurement of 228Ra/226Ra ratios and Ra concentrations in seawater samples by multi-collector ICP mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011;26:1338–1346. doi: 10.1039/c1ja10013k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rapp I, Schlosser C, Rusiecka D, Gledhill M, Achterberg EP. Automated preconcentration of Fe, Zn, Cu, Ni, Cd, Pb, Co, and Mn in seawater with analysis using high-resolution sector field inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;976:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vieira, L. H. Radium Isotopes as Tracers of Element Cycling at Ocean Boundaries. (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, 2019).

- 64.Moore WS. Ages of continental shelf waters determined from 223Ra and 224Ra. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2004;105:22117–22122. doi: 10.1029/1999JC000289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.GEBCO Compilation Group. GEBCO 2019. (GEBCO Compilation Group, 2019). Available at: 10.5285/836f016a-33be-6ddc-e053-6c86abc0788e.

- 66.Wessel P, Smith WHF. A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1996;101:8741–8743. doi: 10.1029/96JB00104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joung DJ, Shiller AM. Temporal and spatial variations of dissolved and colloidal trace elements in Louisiana Shelf waters. Mar. Chem. 2016;181:25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2016.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Symes JL, Kester DR. The distribution of iron in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Chem. 1985;17:57–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-4203(85)90036-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Ruifeng, Zhu Xunchi, Yang Chenghao, Ye Liping, Zhang Guiling, Ren Jingling, Wu Ying, Liu Sumei, Zhang Jing, Zhou Meng. Distribution of dissolved iron in the Pearl River (Zhujiang) Estuary and the northern continental slope of the South China Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 2019;167:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. Source data for dTEs and Ra isotopes are provided as a Source Data File.