Abstract

Background

Observational data and preliminary studies suggest serotonin 2A agonist psychedelics may hold potential in treating a variety of substance use disorders (SUDs), including opioid use disorder (OUD).

Aims

The study aim was to describe and analyze self-reported cases in which naturalistic psychedelic use was followed by cessation or reduction in other substance use.

Methods

An anonymous online survey of individuals reporting cessation or reduction in cannabis, opioid, or stimulant use following psychedelic use in non-clinical settings.

Results

Four hundred forty-four respondents, mostly in the USA (67%) completed the survey. Participants reported 4.5 years of problematic substance use on average before the psychedelic experience to which they attributed a reduction in drug consumption, with 79% meeting retrospective criteria for severe SUD. Most reported taking a moderate or high dose of LSD (43%) or psilocybin-containing mushrooms (29%), followed by significant reduction in drug consumption. Before the psychedelic experience 96% met SUD criteria, whereas only 27% met SUD criteria afterward. Participants rated their psychedelic experience as highly meaningful and insightful, with 28% endorsing psychedelic-associated changes in life priorities or values as facilitating reduced substance misuse. Greater psychedelic dose, insight, mystical-type effects, and personal meaning of experiences were associated with greater reduction in drug consumption.

Conclusions

While these cross-sectional and self-report methods cannot determine whether psychedelics caused changes in drug use, results suggest the potential that psychedelics cause reductions in problematic substance use, and support additional clinical research on psychedelic-assisted treatment for SUD.

Keywords: psychedelics, hallucinogens, psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), addiction, opioid, cannabis, stimulant

Introduction

Substance misuse is a leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality (1, 2), and contributed to over 63,000 drug overdose deaths in the US in 2016 (3). An estimated 23.3 million Americans have met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Ed. (DSM-5; 4) criteria for a substance use disorder (SUD) regarding a drug besides alcohol or tobacco in their lifetime (5). Cannabis, opioids, and cocaine constitute the greatest proportion of these diagnoses (5). Recent trends have shown increased adult use of cannabis (6–8), opioids (9–11), and stimulant drugs (12, 13), and associated adverse public health outcomes (3).

Though cannabis use among those age 12–17 has largely decreased in recent years (6, 14), adults have shown greater use as more states have approved medical or recreational accessibility (8, 15). Concurrently, cannabis related emergency room visits (16) and prevalence of cannabis use disorder have risen (8). The United States has recently seen unprecedented levels of opioid misuse and overdose deaths, including a notable increase in prescription opioid misuse between 2001 and 2013 (17), and over 42,000 opioid-related deaths in 2016 (3). Additionally, recent increases in cocaine and other stimulant use (13, 18–20) have contributed to a substantial number of hospitalizations (21, 22) and deaths (3).

Available SUD treatments typically exhibit limited success with most patients not achieving long-term abstinence (23–26). Medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) include the agonist treatments methadone and buprenorphine, and the opioid antagonist naltrexone (27). However, many people who use opioids are unable or unwilling to access these treatments or do not adhere to them consistently enough to achieve long-term improvement (28–30). There are no approved pharmacotherapies for cannabis (31) and stimulant use disorders (32), and with the exception of contingency management (33, 34), behavioral therapies generally have modest efficacy for treating SUDs (35, 36). Thus, the current public health landscape highlights an urgent need for novel, innovative strategies for treating SUDs.

Use of serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) agonist psychedelics such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin-containing mushrooms (hereafter referred to as psilocybin), peyote, and the dimethyltryptamine (DMT) containing admixture ayahuasca in both naturalistic and clinical settings have been implicated in decreased substance misuse (37–48). The strongest evidence is for LSD in the treatment of alcoholism, with six randomized studies showing an aggregated statistically significant effect for LSD improving outcomes in meta-analysis (49).

An early study in 74 male parolees with a history of chronic heroin use examined a 4- to 6-week residential treatment program involving roughly 5 weeks of preparatory therapy in conjunction with a single high-dose administration of LSD (300–450 µg), compared with treatment as usual outpatient care involving weekly group therapy (46). The LSD treatment was well tolerated among this sample, which was largely African American (76%) and with relatively low education (mean of 8.6 years). Biologically verified continuous abstinence was significantly greater in the LSD than control conditions at 6 month (32% vs. 8%) and 12 month (25% vs 5%) follow-ups (46). Epidemiological data from the 2008–2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed lifetime serotonin 2A agonist psychedelic use was associated with 27% reduced risk of past year opioid dependence and 40% reduced risk of past year opioid abuse when controlling for relevant covariates (43). Preliminary observational data have shown significant reductions in cocaine use in a small sample (n = 6) after participation in a ceremonial ayahuasca retreat geared toward addressing substance misuse (47). Pilot clinical research currently underway has also found promising early results of psilocybin-assisted treatment in people with cocaine use disorder (50, 51). In addition to these preliminary clinical findings, anecdotal reports further corroborate potential benefits of psychedelics in people with various substance use issues (e.g., 52).

We have previously published findings on individuals who self-reported reductions in tobacco (53), and alcohol misuse (40) attributed to naturalistic psychedelic use. However, instances in which people experienced a marked reduction in problematic cannabis, opioid, or stimulant use following ingestion of a psychedelic have not been systematically documented to date. Therefore, the current study sought to characterize instances in which individuals experienced a reduction in cannabis, opioid, or stimulant use after taking a psychedelic in a non-clinical setting. We hypothesized that greater improvements in substance misuse would be associated with greater mystical-type effects of the psychedelic experience consistent with preliminary clinical data (54, 55).

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional, anonymous (i.e., no name or IP address recorded) online survey hosted on SurveyMonkey between October 2015 and August 2017. Study advertisements were posted on social media and on websites devoted to drug discussion, education, or research such as Erowid Center (erowid.org) and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (maps.org). Ads sought individuals who had “overcome alcohol 1 or drug addiction after using psychedelics,” and took interested individuals to a page detailing introductory information regarding the study aims, participation requirements (e.g., filling out a survey), and study inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) able to speak, read, and write English fluently, (3) self-identified as having had problematic cannabis, opioid, or stimulant use, and (4) had used a serotonin 2A agonist psychedelic 2 outside of a research or medical setting, followed by reduction or cessation of subsequent cannabis, opioid, or stimulant use. This study used purposive sampling (56) to specifically seek out people who had experienced improvements in substance use after psychedelic use for two reasons. First, to better characterize these individuals and their experiences, and second, as a preliminary step towards designing and studying psychedelic-assisted interventions for SUDs in clinical settings. People who indicated that they met inclusion criteria, understood the study procedures, and were willing to voluntarily participate were able to begin the survey. Individuals who read the introductory information and then chose to complete the survey were considered to have provided informed consent. Participants were not financially compensated for completing the survey. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Measures

Information on participant demographics and drug use history were collected. Participants' drug use was assessed retrospectively in the periods before and after the psychedelic experience to which they attributed their reduction or cessation in drug use (hereafter referred to as “reference psychedelic experience”). This included ratings of distress related to drug use prior to the reference psychedelic experience, overall duration of drug misuse, use of medication or other SUD treatments before and after the reference psychedelic experience, age of first drug use, and lifetime presence of other mental health diagnoses. 3

Participants provided data on the reference psychedelic experience, including the psychedelic used and approximate dose, type of setting where the experience occurred, intention for self-administering the psychedelic, and any adverse effects or other behavioral changes attributed to the reference psychedelic experience. Participants were asked about possible mechanisms of change attributed to their psychedelic-associated reductions in drug use. Participants also provided ratings of withdrawal symptom severity after the reference psychedelic experience relative to prior attempts to reduce or stop drug use. Further information on the reference psychedelic experience and related changes in drug use patterns was gathered using assessments described below. Participants were asked to identify a specific drug or class of drugs among cannabis, opioids, and stimulants, that was the primary substance of abuse that they reduced or stopped after psychedelic use, and about which they answered specifically targeted questions.

Because this survey was conducted concurrently for people reporting psychedelic-associated reductions in alcohol (40), cannabis, opioid, and stimulant use, some of the measures used here were originally designed and validated to probe alcohol use, and were adapted for this survey to assess other drug use and craving. This was done so that scores on given assessments could be meaningfully compared across drug classes, rather than compared across a number of disparate measures of consumption and/or craving. Participants completed two iterations of a modified version of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (DUDIT-C), the DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Symptom Checklist, and a modified version of the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ), each asking specifically about the primary drug/class of interest (i.e., cannabis, opioids, or stimulants). In the first iteration, participants were asked about their drug use in the year prior to their reference psychedelic experience. In the second, they responded regarding their drug use in the time since the reference psychedelic experience.

DUDIT-C

The DUDIT is an 11-item assessment designed to screen for problematic drug use (57), which largely parallels the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) developed by the World Health Organization to assess alcohol misuse (58). The first three items of the AUDIT probe frequency of drinking, quantity of alcohol use, and frequency of heavy use, and are often used to provide an abbreviated measure of alcohol consumption called the AUDIT-Consumption or AUDIT-C (59, 60). For this survey we administered a modified version of the DUDIT asking specifically about frequency of drug use, quantity used, and frequency of heavy use regarding the specific drug of choice identified by the participant (i.e., cannabis, opioids, or stimulants) to provide an overall score of drug consumption we identify here as DUDIT-C.

DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Symptom Checklist

This checklist was modified to assess DSM-5 symptoms for past and current cannabis, opioid, and stimulant use disorder (4, 61). Participants endorsed whether each of the 11 diagnostic criteria for SUD were true or false based on their drug use in the year before their reference psychedelic experience, and in the time since the reference psychedelic experience. According to DSM-5 criteria, presence of 2–3 symptoms indicates a mild, four to five symptoms indicate a moderate, and six or more symptoms indicate a severe SUD (4).

Drug Urge Questionnaire (DUQ)

This instrument is a modified version of the eight-item Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ; 62). The AUQ is a validated alcohol craving measure that assesses three domains: (1) desire to drink; (2) expectation of positive effects from drinking; and (3) inability to resist drinking when alcohol is accessible, with scores ranging from 8 to 56, and higher scores indicating greater craving. For this study, items were modified to ask about craving for the specific drug of choice (i.e., cannabis, opioids, or stimulants), rather than alcohol.

Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30)

The MEQ30 is a validated 30-item questionnaire designed to assess mystical-type subjective effects of psychedelics (63–66). There are four major dimensions of the MEQ30: (1) mystical, including feelings of unity, sacredness, and noetic quality (i.e., direct knowledge or insight); (2) positive mood (e.g., awe, joy); (3) transcendence of time and space; and (4) ineffability. Participants completed the MEQ30 regarding their reference psychedelic experience. A “complete” mystical experience was defined by ≥60% of the maximum possible score on each of the four subscales of the MEQ30 (63).

Ratings of Persisting Effects

The personal meaning, psychological challenge, psychological insight, spiritual significance, and change in well-being or life satisfaction attributed to the reference psychedelic experience were rated by respondents (40, 67, 68). Participants rated personal meaning, psychological challenge, and psychological insight on a scale from 1 to 8 (1 = no more than routine, everyday experiences; 7 = among the five most meaningful/challenging/insightful experiences of my life; and 8 = the single most meaningful/challenging/insightful experience of my life). Spiritual significance was rated on a scale from 1 to 6 (1 = not at all; 5 = among the five most spiritually significant experiences of my life; 6 = the single most spiritually significant experience of my life). Change in well-being or life satisfaction was rated on a scale from −3 (decreased very much) to 0 (no change) to +3 (increased very much).

Data Analyses

First, descriptive statistics of background and demographic characteristics, history of psychedelic use and characteristics of psychedelic session, substance use and history of treatment, substance withdrawal symptoms, and psychiatric history were calculated. Next, all study variables were subjected to chi-square and one-way analysis of variance tests (with between-subject factor for type of substance) to examine whether there were any differences in study variables as a function of the type of substance (cannabis, opioids, stimulants) affected by the psychedelic experience.

DUDIT-C change scores (post-score minus pre-score) were examined to assess how much each participant's overall substance use had changed from pre- to post-psychedelic experience. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the degree to which DUDIT-C change scores were associated with primary study variables (substance, age, country of residence, mean age at time of psychedelic experience, dose of psychedelic, mystical experiences, insight experiences, personal meaning of psychedelic experience, pre-DUDIT-C, substance distress prior to experience, substance craving prior to experience, post-DUDIT-C, age of first substance use). These analyses were conducted using SPSS software v.24 (69).

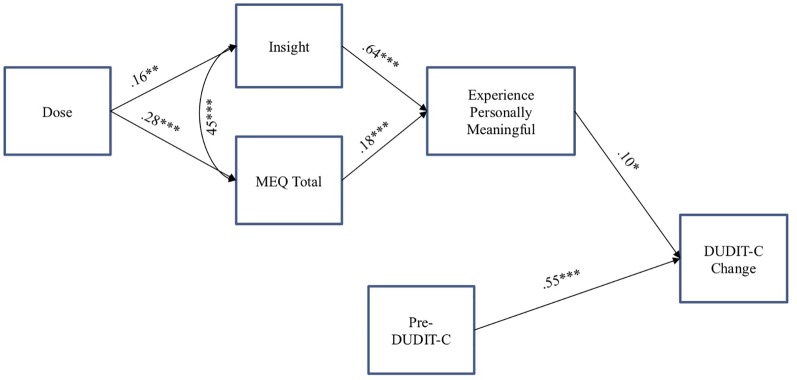

Finally, a path analysis was conducted to examine a model of substance use change associated with a psychedelic experience. The model included (1) Pre-DUDIT-C as a predictor of DUDIT-C change score, (2) dose of the psychedelic as a predictor of acute mystical and insight experiences during psychedelic session, (3) insight and mystical experiences as predictors of ratings of personal meaning associated with the psychedelic session, and (4) personal meaning as a predictor of DUDIT-C change score (see Figure 1 ). We also controlled for the intercorrelation of age with DUDIT-C change score and the intercorrelation of acute mystical and insightful experiences. We conducted this path analysis using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors in MPlus software v.7.0 (70).

Figure 1.

Path analysis examining predictors of substance consumption change score from pre- to post-psychedelic experience among individuals meeting criteria for risky substance use while controlling for the positive association between acute insight and mystical experiences. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. DUDIT-C = Drug Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption. ME, Mystical Experience Questionnaire.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

During data collection (October, 2015 through August, 2017), 3,987 people clicked a recruitment advertisement and started filling out the survey. Of these, 2,556 met all inclusion criteria, provided informed consent, and initiated a response regarding cannabis, opioids, or stimulants. Among these, a total of 630 individuals completed the full survey regarding their use of one of these three classes of substances. Of those that completed the entire survey, 186 respondents were excluded because their reference psychedelic experience occurred within 3 months of filling out the survey, thus limiting the ability to assess lasting change in substance use on the modified DUDIT-C (71). The final sample was comprised of 444 adults. Demographics are presented in Table 1 . The majority were white (82.4%), male (79.1%), and from the U.S. (66.9%), with a mean age of 28.4 (SD = 10.6). Of these, 166 reported they experienced a change in their cannabis use, 155 reported a change in opioid use, and 123 reported a change in stimulant use, following a psychedelic experience. It took participants a median duration of 1 h to complete the survey (inter-quartile range: 0 h 43 min to 1 h 38 min).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, substance use, and mental health history in the sample (N = 444) and in each substance-specific subsample.

| Total sample (N = 444) | Cannabis (n = 166) | Opioids (n = 155) | Stimulants (n = 123) | Post-hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age*** | 28.4 (10.6) | 25.2 (7.8) | 30.6 (11.8) | 29.9 (11.0) | C < O = S |

| Female sex | 93 (20.9%) | 31 (18.7%) | 35 (22.6%) | 27 (22.0%) | |

| White | 365 (82.4%) | 136 (81.9%) | 131 (84.5%) | 98 (80.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 38 (8.6%) | 13 (7.8%) | 14 (9.0%) | 11 (8.9%) | |

| Single/not married | 254 (57.2%) | 105 (63.3%) | 90 (58.1%) | 59 (48.0%) | |

| United States resident*** | 297 (66.9%) | 84 (50.6%) | 123 (79.4%) | 90 (73.2%) | C < O = S |

| Education | |||||

| Did not complete high school/GED | 21 (4.7%) | 11 (6.6%) | 6 (3.9%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| High school/GED | 75 (16.9%) | 33 (19.9%) | 18 (11.6%) | 24 (19.5%) | |

| Some college | 183 (41.2%) | 61 (36.7%) | 75 (48.4%) | 47 (38.2%) | |

| College graduate | 88 (19.8%) | 30 (18.1%) | 30 (19.4%) | 28 (22.8%) | |

| Some grad school or graduate | 77 (17.3%) | 31 (18.7%) | 26 (16.8%) | 20 (16.3%) | |

| Income | |||||

| 0–19.9K | 137 (31.2%) | 58 (35.6%) | 43 (27.7%) | 36 (29.8%) | |

| 20–39.9K | 106 (24.1%) | 35 (21.5%) | 44 (28.4%) | 27 (22.3%) | |

| 40–59.9K | 64 (14.6%) | 28 (17.2%) | 23 (14.8%) | 13 (10.7%) | |

| 60–99.9K | 67 (15.3%) | 20 (12.3%) | 24 (15.5%) | 23 (19.0%) | |

| 100K+ | 65 (14.8%) | 22 (13.5%) | 21 (13.5%) | 22 (18.2%) | |

| Substance use variables and SUD diagnosis | |||||

| Substance distress*** | 2.6 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.2 (2.1) | C < O = S |

| Pre-DUDIT C | 8.0 (2.5) | 8.4 (2.1) | 8.0 (2.6) | 7.7 (2.7) | |

| Pre-DSM5 | |||||

| No SUD | 19 (4.3%) | 9 (5.4%) | 5 (3.2%) | 5 (4.1%) | |

| Mild SUD | 29 (6.5%) | 11 (6.6%) | 7 (4.5%) | 11 (8.9%) | |

| Moderate SUD | 47 (10.6%) | 22 (13.3%) | 12 (7.7%) | 13 (10.6%) | |

| Severe SUD | 349 (78.6%) | 124 (74.7%) | 131 (84.5%) | 94 (76.4%) | |

| Pre-DUQ (Craving)*** | 40.7 (10.4) | 36.6 (9.7) | 45.1 (9.6) | 40.7 (10.2) | C < S < O |

| Post-DUDIT C*** | 2.6 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.8) | 1.8 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.5) | C > S = O |

| Post-DSM5 | |||||

| No SUD | 323 (72.7%) | 109 (65.7%) | 117 (75.5%) | 97 (78.9%) | |

| Mild SUD | 62 (14.0%) | 25 (15.1%) | 22 (14.2%) | 15 (12.2%) | |

| Moderate SUD | 24 (5.4%) | 14 (8.4%) | 3 (1.9%) | 7 (5.7%) | |

| Severe SUD | 35 (7.9%) | 18 (10.8%) | 13 (8.4%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Post DUQ (Craving) | 16.1 (8.9) | 16.4 (9.0) | 16.2 (9.6) | 15.4 (7.8) | |

| Years of having a substance use problem | 4.5 (5.3) | 3.9 (4.8) | 5.4 (5.8) | 4.4 (5.2) | |

| Age of first use*** | 17.2 (4.4) | 15.9 (2.3) | 18.5 (5.4) | 17.2 (4.7) | C < S < O |

| DUDIT-C Change Score*** | -5.4 (3.2) | -4.7 (2.9) | -6.2 (3.4) | -5.6 (3.2) | C < O |

| History of mental health conditions | |||||

| Any mental health disorder | 391 (88.1%) | 141 (84.9%) | 142 (91.6%) | 108 (87.8%) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 277 (62.4%) | 102 (61.4%) | 104 (67.1%) | 71 (57.7%) | |

| Eating disorder | 49 (11.0%) | 21 (12.7%) | 15 (9.7%) | 13 (10.6%) | |

| Impulse control disorder | 31 (7.0%) | 7 (4.2%) | 13 (8.4%) | 11 (8.9%) | |

| Mood disorder | 276 (62.2%) | 104 (62.7%) | 89 (57.4%) | 83 (67.5%) | |

| Personality disorder | 65 (14.6%) | 28 (16.9%) | 12 (7.7%) | 25 (20.3%) | |

| Psychotic disorder | 30 (6.8%) | 8 (4.8%) | 9 (5.8%) | 13 (10.6%) | |

| Substance use disorder*** | 266 (59.9%) | 73 (44.0%) | 122 (78.7%) | 71 (57.7%) | C = S < O |

All values shown are Mean (SD), except where % is noted to indicate n (%). GED, General Education Diploma; DUDIT-C, Drug Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption; DSM5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; 5th Edition; SUD, Substance Use Disorder; DUQ, Drug Urge Questionnaire. ***p < .001.

Substance Use, Mental Health, and Treatment History Prior to Psychedelic Experience

Table 1 shows data regarding participant history of substance use and mental health. Prior to their reference psychedelic experience, 95.7% met criteria for a SUD (severe: 78.6%, moderate: 10.6%, mild: 6.5%). Of the total sample, a minority did not meet DSM-5 criteria for SUD (4.3%) but reported prior problematic use. Mean substance use score on the retrospective DUDIT-C was 8.0 (SD = 2.5), suggesting respondents had a history of heavy substance use, including notable substance use-related consequences before their reference psychedelic experience (recommended AUDIT-C cutoffs for problematic use are ≥4 for men and ≥3 for women; 59). Respondents had been experiencing substance use problems for mean of 4.5 (SD = 5.3) years, had been using their primary substance since the mean age of 17 (SD = 4.4), and the mean reported distress associated with their substance use was between “a moderate amount” and “a lot” (M = 2.6/4, SD = 1.6). Mode responses regarding lifetime psychedelic use ranged from “never used” for peyote (85%), San Pedro (82%), mescaline (80%), ayahuasca (79%), morning glory seeds (70%), and DMT (pure compound; 52%), to 2–5 lifetime psilocybin uses (22%), and 11–20 lifetime LSD uses (17%). Large proportions of the sample had been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (62%), mood disorder (62%), or a SUD not otherwise specified (60%). Table 2 shows SUD treatment history. The majority of participants (59%) had received no treatment for their substance use prior to the reference psychedelic experience, with some having sought treatment via counseling (26%), self-help (17%), or support group (16%).

Table 2.

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) treatment history in the sample (N = 444) and in each substance specific subsample.

| Total sample (N = 444) | Cannabis (n = 166) | Opioids (n = 155) | Stimulants (n = 123) | Post-hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD treatment history prior to psychedelic session | |||||

| None*** | 262 (59.0%) | 122 (73.5%) | 63 (40.6%) | 77 (62.6%) | C = S > O |

| Treatment center/detox*** | 59 (13.3%) | 7 (4.2%) | 41 (26.5%) | 11 (8.9%) | C = S < O |

| Counseling*** | 115 (25.9%) | 24 (14.5%) | 64 (41.3%) | 27 (22.0%) | C = S < O |

| Phone counseling | 13 (2.9%) | 1 (.6%) | 7 (4.5%) | 5 (4.1%) | |

| Website counseling | 30 (6.8%) | 6 (3.6%) | 17 (11.0%) | 7 (5.7%) | |

| Hypnosis | 7 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Acupuncture | 17 (3.8%) | 2 (1.2%) | 11 (7.1%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Support group*** | 72 (16.2%) | 9 (5.4%) | 42 (27.1%) | 21 (17.1%) | C < O = S |

| Self-help | 74 (16.7%) | 17 (10.2%) | 35 (22.6%) | 22 (17.9%) | |

| Spiritual practice | 61 (13.7%) | 17 (10.2%) | 27 (17.4%) | 17 (13.8%) | |

| Medications (for opioid group only) | |||||

| Methadone | – | – | 24 (15.5%) | – | |

| Naltrexone | – | – | 8 (5.2%) | – | |

| Buprenorphine | – | – | 35 (22.6%) | – | |

| SUD treatment history following psychedelic session | |||||

| None*** | 281 (63.3%) | 129 (77.7%) | 73 (47.1%) | 79 (64.2%) | C > S > O |

| Treatment center/detox | 16 (3.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 8 (5.2%) | 6 (4.9%) | |

| Counseling*** | 55 (12.4%) | 9 (5.4%) | 34 (21.9%) | 12 (9.8%) | C = S < O |

| Phone counseling | 4 (.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.9%) | 1 (.8%) | |

| Website counseling | 8 (1.8%) | 4 (2.4%) | 3 (1.9%) | 1 (.8%) | |

| Hypnosis | 4 (.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Acupuncture | 6 (1.4) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Support group | 30 (6.8%) | 5 (3.0%) | 20 (12.9%) | 5 (4.1%) | |

| Self-help*** | 36 (8.1%) | 6 (3.6%) | 25 (16.1%) | 5 (4.1%) | C = S < O |

| Medications (for opioid group only) | |||||

| Methadone | – | – | 5 (3.2%) | – | |

| Naltrexone | – | – | 6 (3.9%) | – | |

| Buprenorphine | – | – | 11 (7.1%) | – | |

| Spiritual practice | 71 (16.0%) | 20 (12.0%) | 36 (23.2%) | 15 (12.2%) |

SUD, Substance Use Disorder. ***p < .001.

Reference Psychedelic Experience

Table 3 shows data regarding the reference psychedelic experience. Approximately three quarters of the sample reported using either LSD (43%) or psilocybin (29%) in the psychedelic experience that contributed to a change in substance misuse. Respondents reported using a moderate (47%), high (33%), or very high (12%) dose and most reported that at least 1 year had passed since their experience (70%), with 20% reporting 6 or more years since their experience. As Table 3 shows, most respondents had their reference psychedelic experience in their home (59%), with the intention for psychological (61%) or spiritual (41%) exploration. Notably, only 14% reported that they intended to reduce/quit their problematic substance use through using the psychedelic substance. Although most participants did not report an explicit intention to change their substance use, 28% of respondents attributed a change in their life priorities or values to their reference psychedelic experience, which was the most commonly reported mechanism for how the psychedelic experience helped change their substance use.

Table 3.

Psychedelic experience locations, intentions, variables, beliefs, and behavioral changes in the sample (N = 444) and in each substance specific subsample.

| Total sample (N = 444) | Cannabis (n = 166) | Opioids (n = 155) | Stimulants (n = 123) | Post-hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of psychedelic experience | |||||

| Home | 260 (58.6%) | 98 (59.0%) | 93 (60.0%) | 69 (56.1%) | |

| Party | 37 (8.3%) | 20 (12.0%) | 8 (5.2%) | 9 (7.3%) | |

| Public place | 30 (6.8%) | 14 (8.4%) | 8 (5.2%) | 8 (6.5%) | |

| Concert | 34 (7.7%) | 9 (5.4%) | 12 (7.7%) | 13 (10.6%) | |

| Nature | 162 (36.5%) | 69 (41.6%) | 48 (31.0%) | 45 (36.6%) | |

| Religious | 45 (10.1%) | 19 (11.4%) | 14 (9.0%) | 12 (9.8%) | |

| Other | 34 (7.7%) | 8 (4.8%) | 16 (10.4%) | 10 (8.1%) | |

| Intention for psychedelic experience | |||||

| No serious intention, other people were using | 14 (3.2%) | 7 (4.2%) | 5 (3.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Curiosity | 73 (16.4%) | 33 (19.9%) | 24 (15.5%) | 16 (13.0%) | |

| Recreation | 231 (52.0%) | 105(63.3%) | 69 (44.5%) | 57 (46.3%) | |

| Psychological self-exploration | 269 (60.6%) | 97 (58.4%) | 94 (60.6%) | 78 (63.4%) | |

| Explore spirituality or the sacred | 180 (40.5%) | 67 (40.4%) | 65 (41.9%) | 48 (39.0%) | |

| To reduce/quit using substance*** | 60 (13.5%) | 7 (4.2%) | 32 (20.6%) | 21 (17.1%) | C < O = S |

| Psychedelic experience variables | |||||

| Psilocybin | 129 (29.1%) | 51 (30.7%) | 43 (27.7%) | 35 (28.5%) | |

| LSD | 192 (43.2%) | 82 (49.4%) | 61 (39.4%) | 49 (39.8%) | |

| Other (e.g., DMT, mescaline) | 123 (27.7%) | 33 (19.9%) | 51 (32.9%) | 39 (31.7%) | |

| Psychedelic dose | |||||

| Very low | 3 (.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (.8%) | |

| Low | 33 (7.4%) | 22 (13.3%) | 4 (2.6%) | 7 (5.7%) | |

| Moderate | 208 (46.8%) | 80 (48.2%) | 67 (43.2%) | 61 (49.6%) | |

| High | 146 (32.9%) | 52 (31.3%) | 58 (37.4%) | 36 (29.3%) | |

| Very high | 54 (12.2%) | 12 (7.2%) | 24 (15.5%) | 18 (14.6%) | |

| Mean age at time of experience*** | 23.7 (7.8) | 21.9 (6.0) | 25.0 (8.7) | 24.7 (8.3) | C < O = S |

| Time since experience | |||||

| 4–6 months | 72 (16.2%) | 32 (19.3%) | 18 (11.6%) | 22 (17.9%) | |

| 7–12 months | 63 (14.2%) | 32 (19.3%) | 17 (11.0%) | 14 (11.4%) | |

| 1–2 years | 112 (25.2%) | 52 (31.3%) | 34 (21.9%) | 26 (21.1%) | |

| 3–5 years | 108 (24.3%) | 30 (18.1%) | 47 (30.3%) | 31 (25.2%) | |

| 6–10 years | 50 (11.3%) | 12 (7.2%) | 23 (14.8%) | 15 (12.2%) | |

| More than 10 years | 39 (8.8%) | 8 (4.8%) | 16 (10.3%) | 15 (12.2%) | |

| MEQ total mean (SD)*** | 66.8 (20.7) | 63.0 (21.4) | 70.8 (20.6) | 66.9 (19.1) | C < O = S |

| MEQ complete mystical experience | 178 (40.1%) | 58 (34.9%) | 75 (48.4%) | 45 (36.6%) | |

| PEQ—personally meaningful | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.4) | |

| PEQ—spiritual significance | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.4) | |

| PEQ—challenging | 3.8 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.2) | |

| PEQ—psychological insight | 5.1 (1.7) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.9) | 5.0 (1.6) | |

| PEQ—change in well-being / life satisfaction | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.9) | C < O = S |

| Proportion ranked each reason as most important for drug use reduction | |||||

| Increased belief in ability to quit | 88 (19.8%) | 26 (15.7%) | 39 (25.2%) | 23 (18.7%) | |

| Reducing stress involved with quitting | 35 (7.9%) | 12 (7.2%) | 15 (9.7%) | 8 (6.5%) | |

| Reframing quitting as a spiritual task | 58 (13.1%) | 16 (9.6%) | 27 (17.4%) | 15 (12.2%) | |

| Changing life priorities or values | 126 (28.4%) | 51 (30.7%) | 34 (21.9%) | 41 (33.3%) | |

| Increased delayed gratification | 83 (18.7%) | 39 (23.5%) | 25 (16.1%) | 19 (15.4%) | |

| Increased ability to cope with craving | 40 (9.0%) | 14 (8.4%) | 13 (8.4%) | 13 (10.6%) | |

| Other behavioral changes after psychedelic experience | |||||

| None | 23 (5.2%) | 6 (3.6%) | 9 (5.8%) | 8 (6.5%) | |

| Reduced/quit other drugs | 251 (56.5%) | 90 (54.2%) | 98 (63.2%) | 63 (51.2%) | |

| Started using other drugs | 41 (9.2%) | 14 (8.4%) | 16 (10.3%) | 11 (8.9%) | |

| Improved diet | 261 (58.8%) | 95 (57.2%) | 98 (63.2%) | 68 (55.3%) | |

| Worsened diet | 12 (2.7%) | 4 (2.4%) | 4 (2.6%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Increased exercise | 255 (57.4%) | 89 (53.6%) | 93 (60.0%) | 73 (59.3%) | |

| Decreased exercise | 11 (2.5%) | 8 (4.8%) | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Improved relationships | 343 (77.3%) | 123 (74.1%) | 129 (83.2%) | 91 (74.0%) | |

| Worsened relationships | 25 (5.6%) | 12 (7.2%) | 7 (4.5%) | 6 (4.9%) | |

| Improved career | 252 (56.8%) | 92 (55.4%) | 91 (58.7%) | 69 (56.1%) | |

| Worsened career | 23 (5.2%) | 10 (6.0%) | 9 (5.8%) | 4 (3.3%) |

LSD, Lysergic acid diethylamide; DMT, N,N-Dimethyltryptamine; MEQ, Mystical Experience Questionnaire; PEQ, Persisting Effects Questionnaire. ***p < .001.

Participant MEQ30 scores were 67% of maximum total score on average, with about 40% of respondents meeting criteria for a “complete mystical experience.” Overall, 76% of respondents rated their reference psychedelic experience among the top 10 most personally meaningful of their lives; 45% rated it among the top 10 most psychologically challenging of their lives; and 71% rated it among the top 10 most psychologically insightful experiences of their lives. Approximately one-half of the sample (51%) rated the reference psychedelic experience among the top 5 most spiritually significant experiences of their lives, and 69% said their sense of well-being or life satisfaction had increased “very much” as a result of the experience and/or contemplation of it. Two individuals (0.5%) reported strong negative change to well-being or life satisfaction attributed to the reference psychedelic experience. One of these described developing “acute HPPD, hallucinogenic perception persistence disorder [sic]” after taking LSD and reported ongoing reduction in cannabis use afterwards. Details regarding the other person who reported strong negative change in well-being are included in the Adverse Effects section below.

Adverse Effects

A majority of respondents (81%) reported no persisting adverse effects from their reference psychedelic experience; 9% reported possible adverse effects (i.e., they were unsure whether there were any adverse effects) and 10% reported definite adverse effects. Those reporting possible or definite adverse effects largely rated them as not severe or slightly severe (59% of the 19% who reported possible or definite adverse effects; e.g., transient paranoia, anxiety). Five individuals (1.1% of the total sample) reported adverse effects rated as extremely severe. Among these five individuals, two reported decreased well-being or life satisfaction related to the reference psychedelic experience (#3, moderately and #4, strongly). Four of the five extreme adverse reactions were in cannabis users, with the remaining (#1) occurring in a stimulant user.

The five extremely severe adverse effects were described as, (1) “The psychedelic experience had me convinced I am heterosexual when actually I am bisexual.” (2) “Night terrors, paranoia. hallucinations; both visual and auditory, feeling like I'm leaving my body, losing my sanity. Many more; these persisted for years.” (3) “Again, the bad trip gave the panic disorder and caused me massive generalized anxiety for half a decade to come. Only with abstinence from cannabis and hallucinogens, tons of medication and therapy for 6 years have I been able to come out on top from this condition of absolute existential dread triggered by the mushroom experience.” (4) “After this overdose, smoking weed gave me painful and disorienting brain zaps. These reduced in severity over approximately 2 weeks and changed into anxiety…. I'm not sure why I even kept smoking, it was a terrible experience but I think I was depressed from the overall after affects and still needed some sort of escape (weed had always been my favorite escape).” (5) “Had nightmares for 6 months and lived in constant fear of death, experienced tactile hallucinations and heard voices for months. Took a long time to process the shame that came through this experience. It's all been beautifully necessary, however.”

Among these individuals reporting extreme adverse reactions, one reported prior history of depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, one reported history of anxiety, mood, personality, and oppositional defiant disorders, one reported a history of anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, one reported a history of anxiety, mood, eating, and personality disorders, and one reported a history of anxiety, mood, personality, and psychotic disorders. Thus, all these individuals reported some mental health conditions that may have been related to or contributed to adverse effects. However, because the survey did not probe whether these issues developed before or after the reference psychedelic experience, no causal attributions can be inferred from the present data.

Substance-Specific Differences in Demographics and Other Variables

As shown in Tables 1 – 3 , few differences were found between cannabis, opioid, and stimulant using groups on demographic variables, substance use and treatment history, and psychedelic-related variables. When differences were found it was frequently the cannabis-using group that was different from the other substance use groups. For example, cannabis users were significantly younger and fewer of them were from the United States, compared to opioid and stimulant users. Additionally, cannabis users had lower mean ratings of substance-related distress, substance craving prior to the reference psychedelic experience, age of first primary substance use, and DUDIT-C change scores compared to opioid and stimulant users. When examining the proportion of respondents who received SUD treatment prior to and following the psychedelic experience, smaller proportions of cannabis and stimulant users had sought treatment including detoxification and counseling, compared to opioid users, but a larger proportion of them had engaged in self-help prior to the psychedelic experience. Furthermore, a larger proportion of opioid users sought treatment following the reference psychedelic experience, and more of them had been previously diagnosed with a substance use disorder, compared to cannabis or stimulant users. Cannabis users also had significantly lower MEQ30 total scores, and ratings of change in well-being or life satisfaction, than opioid users.

Substance-Specific Withdrawal Symptoms

Table 4 shows several withdrawal symptoms were endorsed by roughly two-thirds of the cannabis-using subsample, including depression (68%), craving (66%), and insomnia (66%). Despite experiencing these withdrawal symptoms, many of these respondents (range = 45%–75%) reported that these symptoms were “less severe” or “much less severe” after the reference psychedelic experience compared to prior quit attempts. Although less frequently reported, many respondents endorsed experiencing anxiety (60%), difficulty concentrating (60%), restlessness (57%), irritability (57%), and fatigue (52%). Most reported that the symptom severity was the same or less/much less severe compared to prior quit attempts. Of particular interest, craving appeared to be dampened in those who had previously experienced this withdrawal symptom, with 56% reporting that their cannabis craving was much less severe after the reference psychedelic experience compared to prior quit attempts.

Table 4.

Withdrawal severity after psychedelic-associated cannabis cessation or reduction in comparison with previous quit attempts. (n = 166).

| Withdrawal Symptom | n a | Symptom Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Much less severe | Less severe | Same | More severe | Much more severe | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Lack of appetite | 75 | 18 (24.0%) | 13 (17.3%) | 31 (41.3%) | 12 (16.0%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Fatigue | 87 | 24 (27.6%) | 20 (23.0%) | 30 (34.5%) | 7 (8.0%) | 6 (6.9%) |

| Headaches | 70 | 19 (27.1%) | 15 (21.4%) | 25 (35.7%) | 11 (15.7%) | 0 (.0%) |

| Drowsiness | 72 | 19 (26.4%) | 16 (22.2%) | 24 (33.3%) | 11 (15.3%) | 2 (2.8%) |

| Fever | 24 | 4 (16.7%) | 2 (8.3%) | 17 (70.8%) | 0 (.0%) | 1 (4.2%) |

| Nausea | 34 | 8 (23.5%) | 6 (17.6%) | 17 (50.0%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (.0%) |

| Tremors | 41 | 11 (26.8%) | 6 (14.6%) | 16 (39.0%) | 6 (14.6%) | 2 (4.9%) |

| Increased heart rate | 45 | 11 (24.4%) | 10 (22.2%) | 16 (35.6%) | 4 (8.9%) | 4 (8.9%) |

| Chills | 35 | 9 (25.7%) | 4 (11.4%) | 16 (45.7%) | 5 (14.3%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Seizures | 18 | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0 (.0%) | 0 (.0%) |

| Hallucinations | 30 | 4 (13.3.%) | 3 (10.0%) | 13 (43.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 3 (10.0%) |

| Cravings | 110 | 62 (56.4%) | 20 (18.2%) | 17 (15.5%) | 6 (5.5%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Depression | 113 | 45 (39.8%) | 23 (20.4%) | 20 (17.7%) | 15 (13.3%) | 10 (8.8%) |

| Confusion | 70 | 23 (32.9%) | 13 (18.6%) | 17 (24.3%) | 9 (12.9%) | 8 (11.4%) |

| Heart pounding | 49 | 17 (34.7%) | 4 (8.2%) | 16 (32.7%) | 7 (14.3%) | 5 (10.2%) |

| Difficulty concentrating | 100 | 32 (32.0%) | 25 (25.0%) | 22 (22.0%) | 10 (10.0%) | 11 (11.0%) |

| Irritability | 94 | 30 (31.9%) | 27 (28.7%) | 17 (18.1%) | 15 (18.1%) | 5 (5.3%) |

| Insomnia | 110 | 32 (29.1%) | 17 (15.5%) | 26 (23.6%) | 21 (19.1%) | 14 (12.7%) |

| Restlessness | 95 | 27 (28.4%) | 22 (23.2%) | 23 (24.2%) | 17 (17.9%) | 6 (6.3%) |

| Anxiety | 100 | 28 (28.0%) | 27 (27.0%) | 20 (20.0%) | 12 (12.0%) | 13 (13.0%) |

Sample size varies by symptom (range = 18–113), as some participants had never experienced particular withdrawal symptoms. Percentages were calculated based on the number of individuals who reported a particular withdrawal symptom.

Modal responses shown in bold type.

Table 5 shows approximately three quarters of the opioid-using subsample reported the following withdrawal symptoms after the reference psychedelic experience: depression (77%), irritability (76%), craving (75%), fatigue (74%), muscle aches (72%), insomnia (72%), restlessness (72%), anxiety (71%), and difficulty concentrating (70%). Despite experiencing these withdrawal symptoms, large proportions (range = 49%–75%) rated these symptoms as “less severe” or “much less severe” after the reference psychedelic experience compared to prior quit attempts. Similar to cannabis-using respondents, craving seemed to be attenuated among opioid users who had previously experienced this withdrawal symptom, with 75% reporting that their opioid craving was less or much less severe after the reference psychedelic experience compared to prior quit attempts.

Table 5.

Withdrawal severity after psychedelic-associated opioid cessation or reduction in comparison with previous quit attempts. (n = 155).

| Withdrawal Symptom | n a | Symptom Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Much less severe | Less severe | Same | More severe | Much more severe | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Lacrimation | 92 | 26 (28.3%) | 17 (18.5%) | 39 (42.4%) | 7 (7.6%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 93 | 24 (25.8%) | 20 (21.5%) | 39 (41.9%) | 7 (7.5%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| Fever | 72 | 25 (34.7%) | 11 (15.3%) | 28 (38.9%) | 6 (8.3%) | 2 (2.8%) |

| Muscle aches | 112 | 34 (30.4%) | 21 (18.8%) | 43 (38.4%) | 7 (6.3%) | 7 (6.3%) |

| Diarrhea | 94 | 32 (34.0%) | 17 (18.1%) | 36 (38.3%) | 4 (4.3%) | 5 (5.3%) |

| Headaches | 100 | 32 (32.0%) | 19 (19.0%) | 37 (37.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | 6 (6.0%) |

| Heart pounding | 100 | 26 (26.0%) | 21 (21.0%) | 37 (37.0%) | 8 (8.0%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Drowsiness | 106 | 24 (22.6%) | 24 (22.6%) | 39 (36.8%) | 10 (9.4%) | 9 (8.5%) |

| Chills | 107 | 35 (32.7%) | 24 (22.4%) | 37 (34.6%) | 4 (3.7%) | 7 (6.5%) |

| Insomnia | 111 | 34 (30.6%) | 21 (18.9%) | 37 (33.3%) | 7 (6.3%) | 12 (10.8%) |

| Increased heart rate | 100 | 30 (30.0%) | 23 (23.0%) | 33 (33.0%) | 9 (9.0%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Restlessness | 111 | 30 (27.0%) | 33 (29.7%) | 33 (29.7%) | 6 (5.4%) | 9 (8.1%) |

| Fatigue | 115 | 32 (27.8%) | 33 (28.7%) | 33 (28.7%) | 9 (7.8%) | 8 (7.0%) |

| Cravings | 116 | 58 (50.0%) | 29 (25.0%) | 15 (12.9%) | 6 (5.2%) | 8 (6.9%) |

| Irritability | 118 | 53 (44.9%) | 21 (17.8%) | 28 (23.7%) | 8 (6.8%) | 8 (6.8%) |

| Depression | 120 | 53 (44.2%) | 31 (25.8%) | 19 (15.8%) | 9 (7.5%) | 8 (6.7%) |

| Anxiety | 110 | 44 (40.0%) | 26 (23.6%) | 24 (21.8%) | 8 (7.3%) | 8 (7.3%) |

| Seizures | 33 | 13 (39.4%) | 4 (12.1%) | 12 (36.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Nausea | 98 | 34 (34.7%) | 25 (25.5%) | 29 (29.6%) | 4 (4.1%) | 6 (6.1%) |

| Tremors | 90 | 31 (34.4%) | 19 (21.1%) | 27 (30.0%) | 10 (11.1%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| Lack of appetite | 107 | 34 (31.8%) | 25 (23.4%) | 32 (29.9%) | 10 (9.3%) | 6 (5.6%) |

| Difficulty concentrating | 109 | 33 (30.3%) | 24 (22.0%) | 33 (30.3%) | 10 (9.2%) | 9 (8.3%) |

Sample size varies by symptom (range = 33–120), as some participants had never experienced particular withdrawal symptoms. Percentages were calculated based on the number of individuals who reported a particular withdrawal symptom.

Modal responses shown in bold type.

Table 6 shows more than three quarters of the stimulant-using sample reported the following withdrawal symptoms after the reference psychedelic experience: depression (84%), irritability (79%), craving (77%), anxiety (77%), and difficulty concentrating (76%). Despite experiencing these withdrawal symptoms, large proportions (range = 53%–65%) reported that these symptoms were “less severe” or “much less severe” after the reference psychedelic experience compared to prior quit attempts. Similar to cannabis- and opioid-using respondents, craving seemed to be attenuated among stimulant users who had previously experienced this withdrawal symptom, with 65% reporting that their stimulant craving was less or much less severe compared to prior quit attempts.

Table 6.

Withdrawal severity after psychedelic-associated stimulant cessation or reduction in comparison with previous quit attempts. (n = 123).

| Withdrawal Symptom | n a | Symptom Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Much less severe | Less severe | Same | More severe | Much more severe | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Fever | 46 | 8 (17.4%) | 9 (19.6%) | 26 (56.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Heart pounding | 73 | 16 (21.9%) | 21 (28.8%) | 29 (39.7%) | 4 (5.5%) | 3 (4.1%) |

| Psychomotor retardation | 75 | 20 (26.7%) | 23 (30.7%) | 27 (36.0%) | 4 (5.3%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Increased appetite | 87 | 15 (17.2%) | 19 (21.8%) | 31 (35.6%) | 17 (19.5%) | 5 (5.7%) |

| Drowsiness | 87 | 17 (19.5%) | 23 (26.4%) | 30 (34.5%) | 12 (13.8%) | 5 (5.7%) |

| Unpleasant dreams | 70 | 13 (18.6%) | 22 (31.4.%) | 23 (32.9%) | 7 (10.0%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Increased heart rate | 77 | 18 (23.4%) | 24 (23.4%) | 25 (32.5%) | 8 (10.4%) | 2 (2.6%) |

| Psychomotor agitation | 69 | 19 (27.5%) | 18 (26.1%) | 21 (30.4%) | 8 (11.6%) | 3 (4.3%) |

| Difficulty concentrating | 93 | 24 (25.8%) | 25 (26.9%) | 28 (30.1%) | 10 (10.8%) | 6 (6.5%) |

| Headaches | 83 | 20 (24.1%) | 22 (26.5%) | 24 (28.9%) | 11 (13.3%) | 6 (7.2%) |

| Restlessness | 89 | 19 (21.3%) | 31 (34.8%) | 20 (22.5%) | 14 (15.7%) | 5 (5.6%) |

| Confusion | 68 | 16 (23.5%) | 23 (33.8%) | 22 (32.4%) | 7 (10.3%) | 0 (.0%) |

| Irritability | 97 | 27 (27.8%) | 31 (32.0%) | 18 (18.6%) | 15 (15.5%) | 6 (6.2%) |

| Fatigue | 88 | 20 (22.7%) | 26 (29.5%) | 26 (29.5%) | 12 (13.6%) | 4 (4.5%) |

| Insomnia | 87 | 17 (19.5%) | 24 (27.6%) | 24 (27.6%) | 13 (14.9%) | 9 (10.3%) |

| Cravings | 95 | 40 (42.1%) | 22 (23.2%) | 18 (18.9%) | 8 (8.4%) | 7 (7.4%) |

| Anxiety | 95 | 33 (34.7%) | 30 (31.6%) | 16 (16.8%) | 11 (11.6%) | 5 (5.3%) |

| Depression | 103 | 35 (34.0%) | 29 (28.2%) | 17 (16.5%) | 13 (12.6%) | 9 (8.7%) |

Sample size varies by symptom (range = 46–103), as some participants had never experienced particular withdrawal symptoms. Percentages were calculated based on the number of individuals who reported a particular withdrawal symptom.

Modal responses shown in bold type.

Substance Consumption Following the Psychedelic Experience

Over 70% of participants (n = 331) reported that they had greatly reduced or quit using their primary substance following their reference psychedelic experience as evidenced by an average DUDIT-C change score of −5.4 (SD = 3.2; range = 4 to −12). Though 95.7% met SUD criteria before the reference psychedelic experience, only 27.3% met criteria for a SUD in the time since their reference psychedelic experience. Small proportions continued to meet criteria for mild (14%), moderate (5%), and severe (8%) SUDs. Overall, the average post-DUDIT-C score (M = 2.6; SD = 2.8) suggested that most respondents were no longer using substances above the threshold for which he/she would be considered a risky substance user based on established cutoffs for the AUDIT-C (≥4 for males, ≥3 for females; 59). Additionally, most participants (63%) did not seek other treatment for substance use after their reference psychedelic experience, but smaller proportions noted they engaged in a spiritual practice (16%), had received counseling (12%), or attended a support group (7%).

Path Analysis

Table 7 shows Pearson correlations among variables. As shown in the table, greater decreases in consumption as quantified by DUDIT-C change scores were significantly associated with greater age, ratings of the experience as personally meaningful and insightful, pre-DUDIT-C scores, and intensity of substance use distress. Aside from significant correlations with DUDIT-C change scores, clusters of variables within the overall matrix that were significantly positively correlated included mystical and persisting effects of the reference psychedelic experience (e.g., greater MEQ30 scores associated with greater meaning and insight), and substance use variables (e.g., greater pre-DUQ craving associated with greater substance-related distress).

Table 7.

Correlation among study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DUDIT-C change score | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.56 | −0.67 | −0.01 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| 2 | Age | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| 3 | Country | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.13 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 | |||

| 4 | Substance distress | 0.30 | 0.06 | −0.17 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||||

| 5 | Pre-DUQ Craving | 0.50 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.16 | |||||

| 6 | Pre DUDIT-C | 0.24 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | ||||||

| 7 | Post DUDIT-C | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.01 | |||||||

| 8 | Age of first use | 0.42 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.03 | ||||||||

| 9 | Mean age at time of experience | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | |||||||||

| 10 | MEQ Mean | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.28 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Insight | 0.73 | 0.17 | |||||||||||

| 12 | Meaning | 0.18 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Dose |

Bolded values are significant correlations at p < .001 (conservative alpha). DUDIT-C, Drug Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption; DUQ, Drug Urge Questionnaire; MEQ, Mystical Experience Questionnaire.

Based on previously published survey data among individuals reporting reductions in alcohol consumption after taking a serotonin 2A agonist psychedelic (40), and informed by the present correlation data on variables associated with change in DUDIT-C substance use scores, a path analysis was conducted examining a proposed model to explain the effect of psychedelic consumption on problematic substance use reduction ( Figure 1 ). While controlling for the positive association between acute insight and mystical experiences, greater substance consumption prior to the reference psychedelic experience (pre-DUDIT-C) was directly related to greater change in substance use (DUDIT-C change score). Higher doses of the psychedelic substance were directly related to higher intensity of acute mystical and insight experiences during the psychedelic session, both of which were directly related to greater personal meaning of the experience. Moreover, higher ratings of personal meaning were directly related to greater DUDIT-C change score. Two indirect effects were also found between greater intensity of acute mystical effects [β = .02, SE = .01, p < .05, 95% CI (.00,.03)] and insight [β = .07, SE = .03, p < .05, 95% CI (.01,.11)] on higher DUDIT-C change score via higher ratings of personal meaning. Model fit was good, X 2 (7, N = 444) = 10.13, p = .181; root-mean-square error of approximation = .03 [CI (.00,.07)], standardized root-mean-square residual = .040, and Tucker-Lewis index = .99.

Discussion

The current study provides data on 444 individuals who self-reported reductions in cannabis, opioid, and stimulant misuse after taking a psychedelic drug in a non-clinical setting. The majority of respondents retrospectively reported meeting DSM-5 criteria for severe SUD before their psychedelic experience, whereas in the time since that experience, the majority no longer met criteria for any SUD. Most of the respondents claimed lasting reductions in their substance use for over 1 year after using a psychedelic, consistent with persisting benefits observed in laboratory studies with psilocybin (54, 55, 72–74). Serious adverse effects, though relatively rare, were reported and included both ongoing perceptual disturbances described as hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD; 75), and persisting psychotic symptoms such as paranoia and hallucinations. These were more common among individuals reporting reductions in cannabis use after the reference psychedelic experience, possibly related to observed associations between cannabis use and psychosis (76). Despite adverse events being rare, these data highlight the potential risks of psychedelic use in naturalistic settings by individuals who have not received medical screening or preparation, as is common practice in clinical trials involving psychedelic administration (77). A minority of the present sample (range = 2.5–9.2%) reported negative impacts on overall life adjustment, including increased use of other drugs ( Table 3 ), indicating some cases in which outcomes may have been mixed or otherwise undesirable. Such cases warrant further study to examine what factors may be associated with these challenges.

The findings of the present study are limited by the nature of the anonymous, retrospective self-report data collected, which cannot be verified, and are subject to participant self-selection and recall bias. The cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inferences to be derived from the findings, nor is this study able to provide any information regarding the overall prevalence of psychedelic-associated reductions in other substance use. The purposive sampling used in the current study specifically sought out people reporting positive outcomes regarding substance misuse after naturalistic psychedelic use to characterize these cases, therefore data were not explicitly collected on instances where psychedelic use led to no change or exacerbation of drug misuse. This method limits our ability to generalize these findings across all psychedelic users with other substance misuse issues (e.g., 78, 79), but provides valuable information for designing future psychedelic-assisted treatments for SUD. Additionally, because the survey sought to assess changes in drug use across several pharmacological classes, modified versions of alcohol assessments (AUDIT-C and AUQ) were used, which have not been validated for use in this manner. Due to these limitations, the current data should be interpreted with caution. However, taken in combination with preliminary clinical findings (46, 49, 54, 80) and previous anonymous survey studies (40, 55), these results further bolster the potential utility of serotonergic psychedelics as aids in the treatment of addiction.

Congruent with findings from prior surveys on individuals reporting reductions in tobacco (55) and alcohol consumption (40) after naturalistic psychedelic use, the current sample reported cravings for their primary problematic substance to be less or much less severe than previous attempts to reduce or stop using ( Tables 4 – 6 ). While the veracity and underpinnings of such psychedelic-associated craving reductions remain uncertain, that these patterns of responses are stable across several unrelated drug classes is noteworthy and points to a potential mechanism by which psychedelics may help reduce subsequent substance misuse. Although lifetime psychedelic use was queried, we did not collect the information necessary to make any chronological inference regarding whether reference psychedelic experiences that were closer to initial psychedelic use were more or less likely to impact other substance misuse, a question that remains for future research.

Participants also reported less severity of anxiety and depression symptoms after the reference psychedelic experience compared with other attempts to reduce their substance use. A growing body of literature has shown persisting anxiolytic effects of psilocybin (81–83) and LSD (84), and antidepressant effects of psychedelics including psilocybin (85–87) and ayahuasca (88). Furthermore, data suggest ayahuasca's antidepressant effects are associated with post-acute modulation of cortisol (89) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; 90), shedding light on possible biological mechanisms of psychedelics' lasting mood effects. In turn, reductions in anxiety and depressed mood may also help individuals remain abstinent from drugs in the post-acute “after-glow” period by improving their outlook and ability to manage withdrawal (91, 92).

Additionally, participants endorsed changes in life priorities or values, increased belief in their ability to abstain, and increased ability to delay gratification, as among the most important reasons their psychedelic experience impacted other substance use. These data are in agreement with prior surveys of people reporting psychedelic-associated reductions in tobacco (55) and alcohol consumption (40), and are in accordance with hypotheses regarding psychedelic-related changes in values, self-efficacy, and decision-making as relevant psychological mechanisms for addiction treatment (93–96). As in prior surveys on psychedelic-associated reductions in alcohol consumption (40) participants reported high levels of personal meaning, psychological insight, and mystical-type effects, which were associated with higher psychedelic dose and greater reported change in drug consumption after the psychedelic experience. Thus, the psychological impact of these experiences and acute subjective drug effects seem to play an important role in facilitating subsequent change in substance misuse as observed in pilot studies of psilocybin-assisted interventions for tobacco (55, 97) and alcohol dependence (54).

Preclinical data are further elucidating our understanding of psychedelics' biological mechanisms, with recent findings showing serotonergic psychedelics can promote structural and functional neural plasticity (98), and have potent anti-inflammatory effects (99), which may be correlated with observed therapeutic benefits. Animal models suggest diverse anti-addictive properties of serotonergic psychedelics for alcohol (100, 101) as well as other drugs of abuse. Ayahuasca has been shown to reduce amphetamine self-administration in adolescent rats and normalize amphetamine related locomotor behavior (102). Vargas-Perez and colleagues found a single administration of the serotonin 2A agonist psychedelic 4-AcO-DMT (103) prevented development of opioid and nicotine dependence and blunted withdrawal response in rats and mice (104). Together, these data suggest serotonin 2A psychedelics may hold considerable potential as novel therapeutics in treating various SUDs.

Although medications for opioid use disorder exist, the present opioid overdose rates indicate the need for different treatment avenues (3, 29, 30). For cannabis (31) and stimulant (32) use disorders there are no approved medications at present and limited treatment options, underscoring the necessity for new treatments and approaches. Psychedelic-assisted interventions for addictions may offer an attractive alternative to current treatment models in that they may result in lasting change in substance misuse after only one or a few psychedelic administration sessions (e.g., 55). Importantly, serotonin 2A psychedelics are not themselves physiologically addictive (105), yet they seemingly enhance processes often targeted by accepted addiction treatments such as insight, self-efficacy, and spirituality, which may underlie these lasting effects (93, 94, 96). While challenges remain for the development of psychedelics as medications (106, 107), converging evidence reveals a compelling signal of efficacy. Given the current public health landscape and state of addiction treatment (1, 3), this potential demands rigorous clinical research efforts and federal funding. Although psychedelics might not be a “magic bullet” to solve the pervasive issues of substance misuse and addiction, they may well constitute a much-needed addition to our current armamentarium of medication-assisted treatment for SUDs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this article are not publicly available. Data may be made available on a case by case basis at the discretion of the Principal Investigator.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required as per local legislation and national guidelines.

Author Contributions

AG-R made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition and interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the manuscript. AD made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the manuscript. EE made substantial contributions to the design of the study, participant recruitment, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. FE made substantial contributions to the design of the study, participant recruitment, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. RG made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and made critical revisions to the manuscript. MJ made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition and interpretation of the data, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Heffter Research Institute, and by Tim Ferriss, Matt Mullenweg, Craig Nerenberg, Blake Mycoskie, and the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Foundation. Support for AG-R and AD was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant T32DA07209. Support for RG was provided in part by NIDA Grant R01DA003889.

Conflict of Interest

RG is on the board of directors of the Heffter Research Institute.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Grant Glatfelter, PhD, Toni White, BA, Jefferson Mattingly, BA, and Nora Belblidia, MPS assisted in data collection.

Footnotes

Data on alcohol were previously published elsewhere. See (40).

i.e., psilocybin [magic] mushrooms, LSD, morning glory seeds, mescaline, peyote or San Pedro cactus, DMT, or Ayahuasca.

A copy of the survey questionnaire is available online ( Supplementary Material ).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00955/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet (2012) 379(9810):55–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. Am J Transplant (2016) 16(4):1323–7. 10.1111/ajt.13776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants—united states, 2015–2016. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep (2018) 67(12):349–58. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73(1):39–47. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, Lyerla R. National estimates of marijuana use and related indicators—national survey on drug use and health, United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries (2016) 65(No. SS-11):1–25. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6511a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. Recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use and associated disorders in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73(3):300–1. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry (2015) 72(12):1235–42. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Internal Med (2017. b) 167(5):293. 10.7326/M17-0865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martins SS, Sarvet A, Santaella-Tenorio J, Saha T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Changes in US lifetime heroin use and heroin use disorder: prevalence from the 2001-2002 to 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry (2017) 74(5):445–55. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schepis TS, McCabe SE. Trends in older adult nonmedical prescription drug use prevalence: Results from the 2002–2003 and 2012–2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behav (2016) 60:219–22. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Compton WM. National trends in and correlates of nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, nonmedical use frequency, and Use Disorders. J Clin Psychiatry (2017. a) 78(9):e1250–8. 10.4088/JCP.17m11760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. John WS, Wu L-T. Trends and correlates of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder in the United States from 2011 to 2015. Drug Alcohol Depend (2017) 180:376–84. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson RM, Fairman B, Gilreath T, Xuan Z, Rothman EF, Parnham T, et al. Past 15-year trends in adolescent marijuana use: Differences by race/ethnicity and sex. Drug Alcohol Depend (2015) 155:8–15. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Stohl M, Galea S, et al. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry (2017) 74(6):579–88. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu H, Wu L-T. Trends and correlates of cannabis-involved emergency department visits: 2004 to 2011. J Addict Med (2016) 10(6):429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry (2016) 77(6):772. 10.4088/JCP.15m10386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kerridge BT, Chou SP, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Jung J, et al. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. Addictive Behav (2019) 90:250–7. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piper BJ, Ogden CL, Simoyan OM, Chung DY, Caggiano JF, Nichols SD, et al. Trends in use of prescription stimulants in the United States and Territories, 2006 to 2016. PloS One (2018) 13(11):e0206100. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen L-Y, Crum RM, Strain EC, CalebAlexander G, Kaufmann C, Mojtabai R. Prescriptions, nonmedical use, and emergency department visits involving prescription stimulants. J Clin Psychiatry (2016) 77(3):e297–304. 10.4088/JCP.14m09291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saxena A, Rubens M, Das S, Ramamoorthy V, McGranaghan P, Veledar E. Abstract 17208: Trends in hospitalizations due to cocaine-induced acute Myocardial Infarction: Results From National Inpatient Sample, 2005-2014. Circulation (2018) 138(Suppl_1):A17208–8. 10.1161/circ.138.suppl_1.17208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anglin MD, Hser Y-I, Grella CE. Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychol Addictive Behav (1997) 11(4):308–23. 10.1037/0893-164X.11.4.308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM. Drug abuse treatment: A national study of effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2002) 59(6):538–44. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychol Addictive Behav (1997) 11(4):294. 10.1037/0893-164X.11.4.294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harvard Rev Psychiatry (2015) 23(2):63–75. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health (2015) 105(8):e55–63. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saloner B, Karthikeyan S. Changes in substance abuse treatment use among individuals with opioid use disorders in the United States, 2004-2013. JAMA (2015) 314(14):1515–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.10345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. New Engl J Med (2014) 370(22):2063–6. 10.1056/NEJMp1402780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brezing CA, Levin FR. The current state of pharmacological treatments for cannabis use disorder and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology (2018) 43(1):173–94. 10.1038/npp.2017.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan B, Kondo K, Ayers C, Freeman M, Montgomery J, Paynter R, et al. (2018). Pharmacotherapy for Stimulant Use Disorders: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Dept. of Veterans Affairs; Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536789/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction (2006) 101(11):1546–60. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stitzer ML, Vandrey R. Contingency management: utility in the treatment of drug abuse disorders. Clin Pharmacol Ther (2008) 83(4):644–7. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, Foll BL, Gowing L. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2016)(5):CD005336. 10.1002/14651858.CD005336.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knapp WP, Soares B, Farrell M, Silva de Lima M. Psychosocial interventions for cocaine and psychostimulant amphetamines related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2007) 3:CD003023. 10.1002/14651858.CD003023.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barbosa PCR, Mizumoto S, Bogenschutz MP, Strassman RJ. Health status of ayahuasca users. Drug Test Anal (2012) 4(7–8):601–9. 10.1002/dta.1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blum K, Futterman SFL, Pascarosa P. Peyote, a potential ethnopharmacologic agent for alcoholism and other drug dependencies: possible biochemical rationale. Clin Toxicol (1977) 11(4):459–72. 10.3109/15563657708988210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fábregas JM, González D, Fondevila S, Cutchet M, Fernández X, Barbosa PCR, et al. Assessment of addiction severity among ritual users of ayahuasca. Drug Alcohol Depend (2010) 111(3):257–61. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid F, Erowid E, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol (2019) 33(9):1088–101. 10.1177/0269881119845793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halpern JH. Hallucinogens in the treatment of alcoholism and other addictions. In: . Psychedelic medicine: New evidence for hallucinogenic substances as treatments, vol. 2 . Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, US: (2007). p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halpern JH, Sherwood AR, Passie T, Blackwell KC, Ruttenber AJ. Evidence of health and safety in American members of a religion who use a hallucinogenic sacrament. Med Sci Monitor (2008) 14(8):SR15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pisano VD, Putnam NP, Kramer HM, Franciotti KJ, Halpern JH, Holden SC. The association of psychedelic use and opioid use disorders among illicit users in the United States. J Psychopharmacol (2017) 31(5):606–13. 10.1177/0269881117691453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prue B. Indigenous supports for recovery from alcoholism and drug abuse: The Native American Church. J Ethnic Cult Diversity Soc Work (2013) 22(3–4):271–87. 10.1080/15313204.2013.843138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rios MDde, Grob CS, Baker JR. Hallucinogens and Redemption. J Psychoactive Drugs (2002) 34(3):239–48. 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Savage C, McCabe OL. Residential psychedelic (LSD) therapy for the narcotic addict: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1973) 28(6):808–14. 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750360040005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thomas G, Lucas P, Capler NR, Tupper KW, Martin G. Ayahuasca-assisted therapy for addiction: results from a preliminary observational study in Canada. Curr Drug Abuse Rev (2013) 6(1):30–42. 10.2174/15733998113099990003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Winkelman M. Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca. Curr Drug Abuse Rev (2014) 7(2):101–16. 10.2174/1874473708666150107120011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krebs TS, Johansen P al-Ø. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol (2012) 26(7):994–1002. 10.1177/0269881112439253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hendricks PS. Psilocybin treatment of cocaine use disorder . In: . Presented at the College on Problems of Drug Dependence 80th Annual Scientific Meeting, San Diego, CA. Brentwood, TN: The College on Problems of Drug Dependence; (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 51. Johnson MW. Psychedelics in the treatment of addiction. In: Grob CS, editor. Handbook of Medical Hallucinogens. Guilford Press: New York, NY: (In Press). [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roes T. (2014). I Quit Smoking After an LSD Trip. New York, NY: Vice Media; Retrieved July 25, 2019, from Vice website: https://www.vice.com/sv/article/5gkq4x/quit-smoking-with-lsd-876. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Johnson PS, Griffiths RR. An online survey of tobacco smoking cessation associated with naturalistic psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol (2017) 31(7):841–50. 10.1177/0269881116684335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol (2015) 29(3):289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse (2017) 43(1):55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat (2016) 5(1):1–4. 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]