Abstract

The effects of the selective 5HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT were assessed on the play behavior of juvenile rats. When both rats of the test pair were comparably motivated to play, the only significant effect of 8-OH-DPAT was for play to be reduced at higher doses. When there was a baseline asymmetry in playful solicitation due to a differential motivation to play and only one rat of the pair was treated, low doses of 8-OH-DPAT resulted in a collapse of asymmetry in playful solicitations. It did not matter whether the rat that was treated initially accounted for more nape contacts or fewer nape contacts, the net effect of 8-OH-DPAT in this model was for low doses of 8-OH-DPAT to decrease a pre-established asymmetry in play solicitation. It is concluded that selective stimulation of 5HT1A receptors changes the dynamic of a playful interaction between two participants that are differentially motivated to play. These results are discussed within a broader framework of serotonergic involvement in mammalian playfulness.

Keywords: Play, Serotonin, 5HT1A, Autoreceptors, 8-OH-DPAT, Motivation, Rat

1. Introduction

Play is a fundamental neurobehavioral process that is shared widely among the juveniles of most mammalian species, several avian and reptilian species, and even among some invertebrates (Burghardt, 2005, Fagen, 1981, Pellis and Pellis, 2009). Play has been particularly well characterized in the rat (Panksepp, 1998, Panksepp et al., 1984, Pellis and Pellis, 2009, Trezza et al., 2010, Vanderschuren et al., 1997) and shows a distinctive ontogenetic trajectory, appearing in the behavioral repertoire shortly after independent locomotion begins, peaking at around 35 days of age and then steadily decreasing as puberty approaches (Meaney and Stewart, 1981, Panksepp, 1981, Small, 1899). At its peak, play in the rat accounts for about 3–6% of the daily energy budget and about 3% of the time budget (Siviy and Atrens, 1992, Thiels et al., 1990). There is good evidence that a playful phenotype is heritable as robust differences have been reported between different strains of rats (Ferguson and Cada, 2004, Siviy et al., 1997, Siviy et al., 2003, Siviy et al., 2011) and between rats that have been selectively bred on other related components such as affective vocalizations (Brunelli et al., 2006) and susceptibility to amygdala kindling (Reinhart et al., 2004, Reinhart et al., 2006).

Play is a highly regulated behavior and, in rats, levels of play are exquisitely sensitive to how long it has been since a previous opportunity to play (Panksepp and Beatty, 1980). Rats that have been isolated for 4 h will play more than rats that have not been isolated, while rats that have been isolated for 24 h will play more than rats that have been isolated for 4 h. Play is also affectively positive (i.e., it is fun for the participants). For example, rats will readily learn to navigate a maze where an opportunity to play is the reward (Humphreys and Einon, 1981, Normansell and Panksepp, 1990) and will show a clear preference for a context previously associated with play (Calcagnetti and Schechter, 1992, Douglas et al., 2004, Trezza et al., 2009b). Rats will also emit short (<0.5 s) bursts of high frequency (∼50 kHz) vocalizations when playing and when placed in a context where they have previously played (Knutson et al., 1998a, Knutson et al., 1998b) and these types of vocalizations have also been observed in other affectively positive states (Burgdorf et al., 2000, Burgdorf et al., 2001, Burgdorf et al., 2008, Burgdorf and Panksepp, 2001, Knutson et al., 1999, McIntosh and Barfield, 1980). Taken together, these data suggest that play is a stable behavioral phenotype among most mammals and likely arises from activity in specific neural circuits that are sensitive to motivational and affective processes.

At the neurochemical level, several neurotransmitters have emerged as strong candidates for modulating play. Among these, a specific role for endogenous opioid and cannabinoid systems are particularly prominent. Endogenous opioids are released in many areas of the brain during play (Panksepp and Bishop, 1981, Vanderschuren et al., 1995c) while low doses of morphine increase play and opioid antagonists decrease play (Niesink and Van Ree, 1989, Panksepp et al., 1985, Trezza and Vanderschuren, 2008b, Vanderschuren et al., 1995a, Vanderschuren et al., 1995b, Vanderschuren et al., 1996). Compounds that prevent the breakdown or reuptake of endogenous cannabinoids once released into the synapse also increase play (Trezza and Vanderschuren, 2008a, Trezza and Vanderschuren, 2008b, Trezza and Vanderschuren, 2009), suggesting that a subset of cannabinoid synapses are active during play and that prolonging activity in these synapses makes rats more playful. There is also considerable overlap between opioid and cannabinoid involvement in play as increases in play following enhanced endocannabinoid signaling or with morphine can be blocked by either opioid and cannabinoid CB1 antagonists.

Brain monoamines have long been thought to be involved in the modulation of play. Indeed, one of the first pharmacological studies using play as a measure showed that low doses of psychomotor stimulants such as amphetamine and methylphenidate are very potent in reducing play (Beatty et al., 1982). Given the extent to which dopamine is well known to be involved in other motivational and affective processes it is not surprising to find the imprint of dopamine on play behavior as well. Dopamine utilization increases during play bouts (Panksepp, 1993), dopamine antagonists uniformly reduce play (Beatty et al., 1984, Niesink and Van Ree, 1989, Siviy et al., 1996), and neonatal 6-OHDA lesions impair the sequencing of behavioral elements during play bouts (Pellis et al., 1993). While it has been difficult to obtain consistent increases in play with dopamine agonists (Beatty et al., 1984, Field and Pellis, 1994, Siviy et al., 1996) increases in play following alcohol, nicotine, and indirect cannabinoid agonists can all be blocked by silent doses of dopamine antagonists (Trezza et al., 2009a, Trezza and Vanderschuren, 2008a). These data suggest that play is associated with increased release of dopamine (Robinson et al., 2011), and it has been suggested that an optimal level of dopamine functioning is necessary for play to occur (Trezza et al., 2010).

Both norepinephrine and serotonin have fairly extensive and diffuse projections throughout the forebrain and a specific role for norepinephrine was initially indicated from findings that selective alpha-2 noradrenergic antagonists can increase play while alpha-2 agonists reduce play (Normansell and Panksepp, 1985a, Siviy et al., 1990, Siviy et al., 1994, Siviy and Baliko, 2000). A specific role for alpha-2 receptors is also indicated by the finding that reductions in play following methylphenidate can be reversed by a silent dose of the alpha-2 antagonist RX821002 but not by either an alpha-1 or beta antagonist (Vanderschuren et al., 2008). Vanderschuren et al. (2008) also reported that the play-disrupting effects of methylphenidate could be mimicked by the selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine but not by the selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909. These data suggest that increased synaptic availability of NE is incompatible with play and this is apparently due to action at post-synaptic alpha-2 receptors.

Serotonin is thought to have considerable impact on a wide range of neurobehavioral processes including affective regulation (Dayan and Huys, 2009, Hariri and Holmes, 2006), establishing and maintaining dominance (Huber et al., 2001, Raleigh et al., 1991), and defensive behavior (Blanchard et al., 1998, Graeff, 2002), to name just a few, so it is very likely that serotonin may also be involved in at least some aspect of play. Indeed, augmenting serotonin functioning through acute treatment with either fluoxetine or MDMA (“Ecstasy”) reduces play (Homberg et al., 2007, Knutson et al., 1996). Homberg et al. (2007) reported less play among serotonin transporter knockout rats as well. Although these data would suggest that enhanced serotonergic functioning is incompatible with play, a more complex pattern emerges when only one rat of a pair is treated and attention is paid to the reciprocal interactions between the two rats of the testing pair. When rats were allowed to establish a dominance relationship such that one rat accounted for more pinning than the other (this being the dominant rat) the effects of either fluoxetine or serotonin depletion depended on the status of the rat that was treated. Augmenting serotonin levels through fluoxetine reduced the pinning asymmetry when the dominant rat was treated (Knutson et al., 1996) while depleting serotonin enhanced the pinning asymmetry (Knutson and Panksepp, 1997). Interestingly, these effects were largely due to changes in the behavior of the untreated partner towards the treated partner. Also, treating the subordinate rat had no effect on the pinning asymmetry and playful solicitations were not affected in this set of experiments. These data suggest a more subtle role for serotonin in modulating play behavior that may be more sensitive to interactive cues between the play partners.

In addition to having extensive projection throughout the forebrain, there is also considerable diversity in the receptor mechanisms associated with serotonergic functioning. There are believed to be at least 14 different receptor subtypes for serotonin (Martin and Humphrey, 1994, Millan et al., 2008) although the 5HT1A receptor is the best characterized of these. The 5HT1A receptor is located at both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites and many of the behavioral effects associated with stimulation of this receptor are generally ascribed to a reduction in 5HT release due to stimulation of somato-dendritic autoreceptors (Carboni and Di Chiara, 1989, Hjorth et al., 1982) although stimulation of post-synaptic 5HT1A receptors may also reduce 5HT cell firing and release as well through an indirect feedback pathway (Sharp et al., 2007). In either case, the net effect of stimulating 5HT1A receptors is a reduction in serotonin neurotransmission. As the prototypical agonist for the 5HT1A receptor (Hjorth et al., 1982), the behavioral effects of 8-OH-DPAT have been studied most extensively, yet the effects of this compound on play have not been well characterized. While the complexity of 5HT1A receptor systems may make it difficult to predict exactly how any given dose of systemically administered 8-OH-DPAT reflects a specific change in 5HT functioning (De Vry, 1995), understanding the effects of stimulating 5HT1A receptors seems a necessary step in further defining any role for serotonin in play behavior. Accordingly, the current study sought to determine the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on play in juvenile rats.

2. Experiment 1

Earlier studies from our lab suggested that low autoreceptor-selective doses of 8-OH-DPAT may increase playfulness in young rats (Siviy, 1998) although these effects were neither robust nor easily reproducible. In this first experiment we sought to initially characterize the dose-related effects of 8-OH-DPAT on play. Playful interactions between two rats are very energetic and dynamic, yet play in the rat can be readily characterized primarily by contacts directed towards the nape of the neck and by how rats respond to those contacts. When rats are young the most common response to a nape contact is a complete rotation along the longitudinal axis such that the rat is on its back with all four paws in the air and the other rat on top in what looks like a pinning posture (Panksepp et al., 1984, Pellis and Pellis, 1987, Siviy, 1998, Vanderschuren et al., 1997). Due largely to the contagious nature of play (Pellis and McKenna, 1992) it is often difficult to determine if any pharmacological effect is modifying solicitation, responsiveness, or both if the rats are similarly treated. In order to address this potential concern, the effects of 8-OH-DPAT were assessed when either both rats were similarly treated or when only one rat was treated.

2.1. Materials and methods

2.1.1. Subjects and housing

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were obtained at approximately 19 days of age. Upon arrival and unless stated otherwise in the specific procedures, animals were housed in groups of four in solid bottom cages (48 × 27 × 20 cm) and periodically handled for a few days after arrival in order to acclimate to the laboratory. Food and water were always freely available. The colony room was maintained at 22 °C with a 12/12 h reversed light/dark cycle (lights off at 08:00), with all testing done during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. All housing and testing was done in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Gettysburg College.

2.1.2. Quantifying play

Play behavior was assessed in a clear Plexiglas chamber (40 × 40 × 50 cm) that was enclosed within a sound-attenuated wooden chamber illuminated by a single 25 W red light bulb. The floor of the testing chamber was covered with approximately 3 cm of Aspen pine shavings. Play bouts were recorded as digital video files and scored later using behavioral observation software (Noldus XT: Noldus Information Technology) by an observer unaware of the treatment condition.

Rats were initially acclimated to the testing chamber by being placed individually in the testing chamber for 5 min/day for 2 days prior to testing. For testing rats were placed in the testing chamber and play was quantified by counting the frequency of contacts directed towards the nape (nape contacts) and the likelihood that a nape contact resulted in that rat rotating completely to a supine position (complete rotation). Nape contacts were quantified by frequency of occurrence, while complete rotations were quantified in probabilistic terms by calculating the probability of a complete rotation occurring in response to a nape contact. These two measures of playfulness have been commonly used in this lab and are also thought to be controlled by independent motivational and neural substrates (Pellis and Pellis, 1991, Pellis and Pellis, 1987, Siviy et al., 1997, Siviy and Panksepp, 1987).

2.1.3. Procedures

Eight pairs of rats were used to initially assess the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on play behavior when both rats of the pair were similarly treated. Rats were isolated in solid-bottom cages (27 cm × 21 cm × 14 cm) 4 h prior to testing. Food and water were always available during isolation. For this and all subsequent experiments, four doses of (±)-8-OH-DPAT (0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 mg/kg) and vehicle (0.9% physiological saline) were tested and administered subcutaneously (SC) in the hip 45 min before testing. Every pair received each of the five treatments in a counterbalanced order with at least 48 h separating each test. Rats were tested in the same pairs (cage-mates) for all treatments. Nape contacts and probability of complete rotations reflect values for the pair. Social investigation was also quantified by the relative amount of time spent by either animal sniffing the ano-genital area of their play partner.

In order to assess the extent to which 8-OH-DPAT affected overall activity during play bouts, an additional eight pairs of rats were used to simultaneously monitor both play and locomotor activity. Testing parameters and doses were the same as above. Locomotor activity was monitored by a video-tracking system (Ethovision; Noldus Information Technology) that was capable of tracking the movement of both animals at the same time. In order to facilitate the ability of the software to track the rats, there was no bedding in the test chamber. Play was quantified as it occurred (i.e., these sessions were not taped) by counting the frequency of nape contacts. Locomotor activity was quantified by distance (cm) traveled by both of the rats and by average velocity (cm/s) over the course of the 5 min session.

An additional 14 pairs of rats were used to assess the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on play when only rat of the testing pair was treated. The rat designated to receive 8-OH-DPAT received each of the five treatments in a counterbalanced order, and at least 48 h separated each test. For this experiment, rats were tested with a novel untreated partner on each test day in such a way that the untreated partner was also paired with a rat receiving a different dose each day. Both rats of the test pair were isolated 4 h before testing as described above. Nape contacts and probability of complete rotations were recorded for each rat of the testing pair (treated and untreated). Social investigation was also quantified for each rat of the test pair.

2.2. Results

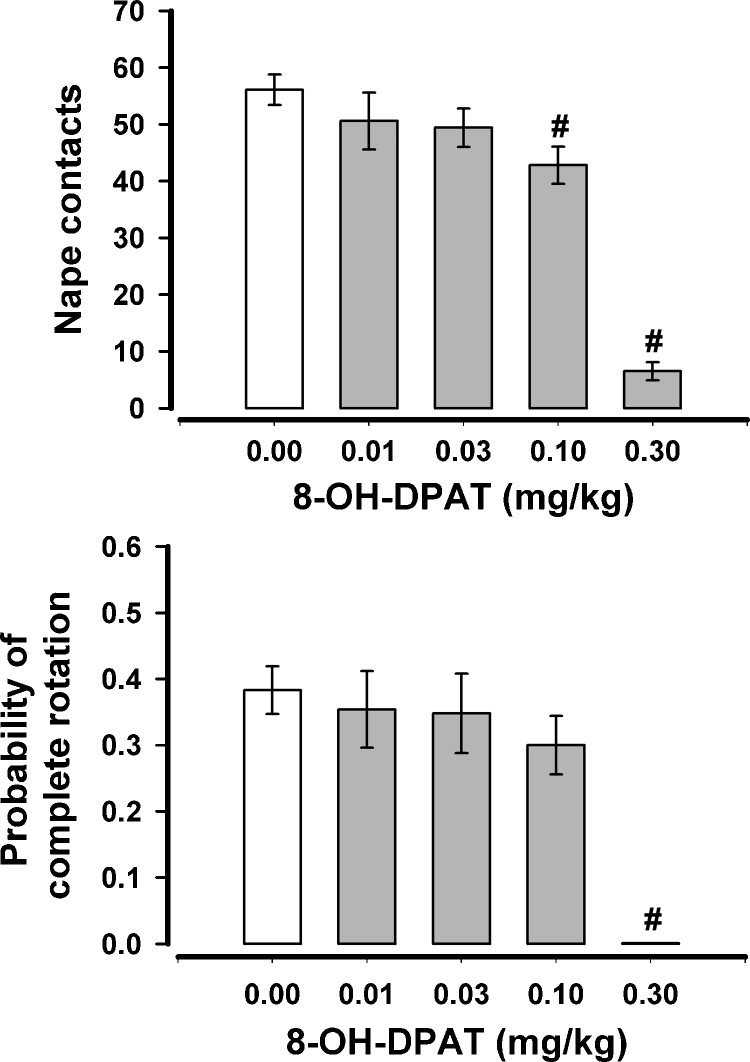

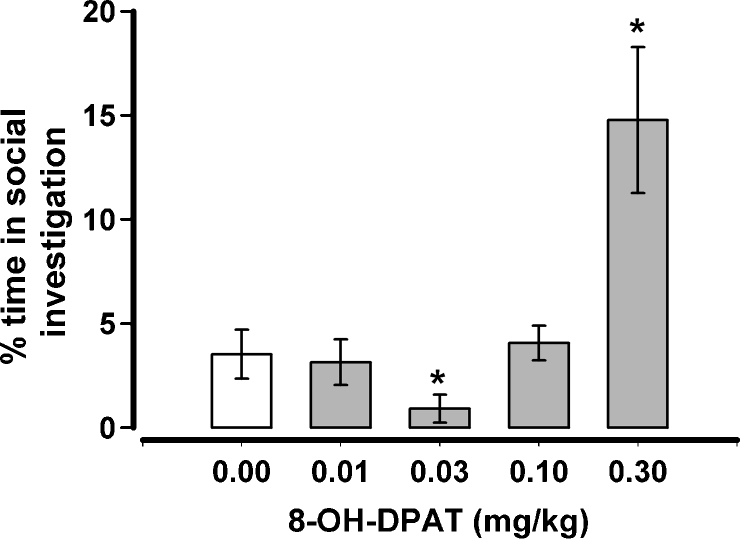

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT when both rats of the test pair were treated and when tested after 4 h of isolation can be seen in Fig. 1. When these data were submitted to a repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) there was found to be a significant effect for nape contacts, F(4,28) = 35.69, p < .001, and for the probability of a complete rotation, F(4,28) = 10.66, p < .001. Nape contacts differed significantly (p < .05, paired comparisons test) from vehicle after the two highest doses (0.1, 0.3 mg/kg) while complete rotations differed significantly from vehicle only after highest dose (0.3 mg/kg). 8-OH-DPAT also had a significant effect on time spent in social investigation, F(4,28) = 9.03, p < .001 (Fig. 2). When compared to vehicle, social investigation significantly decreased after 0.03 mg/kg but increased after 0.3 mg/kg.

Fig. 1.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on nape contacts and the probability of responding to nape contacts with a complete rotation in rats that were isolated for 4 h prior to testing. Both rats of the test pair were treated similarly. #p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg.

Fig. 2.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on social investigation when both rats were treated similarly and both were isolated for 4 h prior to testing. *p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on play and locomotor activity can be seen in Table 1. 8-OH-DPAT had a significant effect on all 3 measures, Fs(4,28) > 9.10, p < .001. The highest dose significantly reduced nape contacts, distance traveled, and average velocity of movement.

Table 1.

Effects of 8-OH-DPAT on nape contacts and locomotor activity.

| 8-OH-DPAT (mg/kg) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| Nape contacts | 16.6 (2.2) |

22.1 (4.1) |

17.5 (2.9) |

12.4 (3.9) |

2.0* (0.7) |

| Distance traveled (cm) | 4698.4 (274.5) |

4762.1 (354.2) |

4595.8 (297.9) |

3912.8 (412.4) |

2473.5* (230.8) |

| Average velocity (cm/s) | 15.7 (0.9) |

15.9 (1.2) |

15.3 (1.0) |

13.1 (1.4) |

8.3* (0.8) |

Notes: numbers in parentheses indicate standard error of the mean.

p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg.

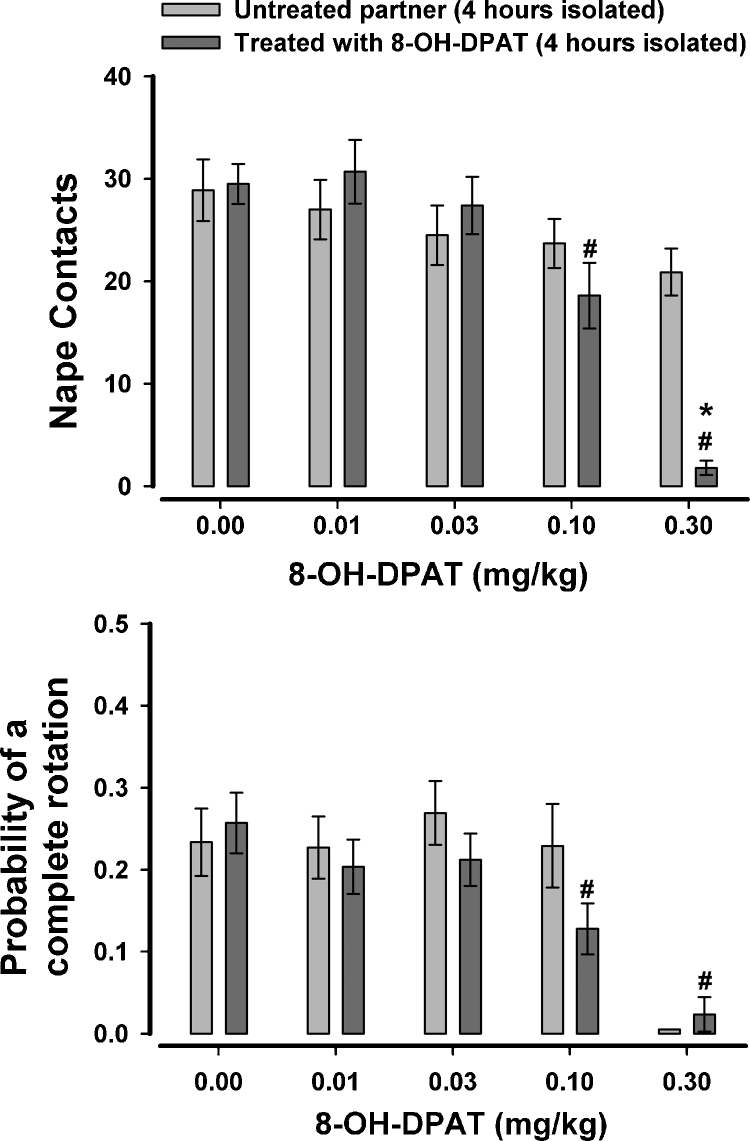

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT when only one rat of a test pair was treated and when both rats were isolated for 4 h prior to testing is shown in Fig. 3. These data were submitted to a 2 × 5 ANOVA with one between-subjects factor for partner (treated or untreated) and one within-subjects factor for the five doses. For nape contacts there was found to be a significant effect of dose, F(4,104) = 15.89, p < .001, a marginal effect of partner, F(1,26) = 4.22, p = .05, and a significant dose × partner interaction, F(4,104) = 6.47, p < .001. Separate ANOVAs were conducted on the data from the treated and untreated partners and it was found that 8-OH-DPAT reduced nape contacts in the treated rats at the two highest doses. Nape contacts for the untreated rat were unaffected by the treatment of the partner. The only significant effect from the analysis of complete rotations was a significant effect of dose, F(4,104) = 6.14, p < .001, with the highest dose reducing the likelihood of responding to a nape contact with a complete rotation. For social investigation there was found to be a significant partner × dose interaction, F(4,104) = 3.02, p = .021 (Fig. 4) with social investigation increasing in the untreated partner when the partner was treated with 0.1 mg/kg of 8-OH-DPAT.

Fig. 3.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on nape contacts and the probability of responding to nape contacts with a complete rotation when only one rat of the test pair was treated. Both rats were isolated for 4 h prior to testing. #p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg; *p < .05 when compared to untreated partner at the same dose level.

Fig. 4.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on social investigation when only one rat of the test pair was treated. Both rats were isolated for 4 h prior to testing. *p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg and when compared to same dose given to treated rat.

3. Experiment 2

The results from the previous experiment showed that the only consistent effect of 8-OH-DPAT was for play to be reduced at higher doses. There was no indication of an increase in play at the lower autoreceptor-selective doses and this is pretty consistent with a number of preliminary studies done in our lab. However, given that the effects of fluoxetine and 5HT depletion on play have been shown to be dependent on an initial asymmetry in pinning between established pairs of rats (Knutson and Panksepp, 1997, Knutson et al., 1996) it seemed reasonable to predict that 8-OH-DPAT may also be sensitive to a pre-existing asymmetry in play. Rather than allowing rats to establish a dominance/subordinate relationship, rats in this experiment played with a new partner on each test day and we sought to establish an asymmetry in play by varying the amount of isolation prior to the play bout. In particular, one rat of a pair was chronically isolated for 24 h while its partner was isolated for only 4 h prior to testing and, as predicted, rats that were isolated for 24 h accounted for more nape contacts than those isolated for 4 h. The effects of 8-OH-DPAT were then assessed when either given to the rat isolated for 24 h or to the rat isolated for 4 h.

3.1. Procedure

Subjects, housing, and testing protocols for play were the same as in Experiment 1. In one experiment (n = 8 pairs), the treated rat was isolated for 4 h prior testing while its untreated partner was isolated for 24 h. In a separate experiment (n = 8 pairs) the treated rat was isolated for 24 h prior to testing while its untreated partner was isolated for 4 h. As in Experiment 1, all injections were given SC 45 min before a 5 min opportunity to play. The rat designated to receive 8-OH-DPAT received each of the five treatments in a counterbalanced order, and at least 48 h separated each test. Rats were tested with a different untreated partner on each test day in such a way that the untreated partner was also paired with a rat receiving a different dose each day.

3.2. Results

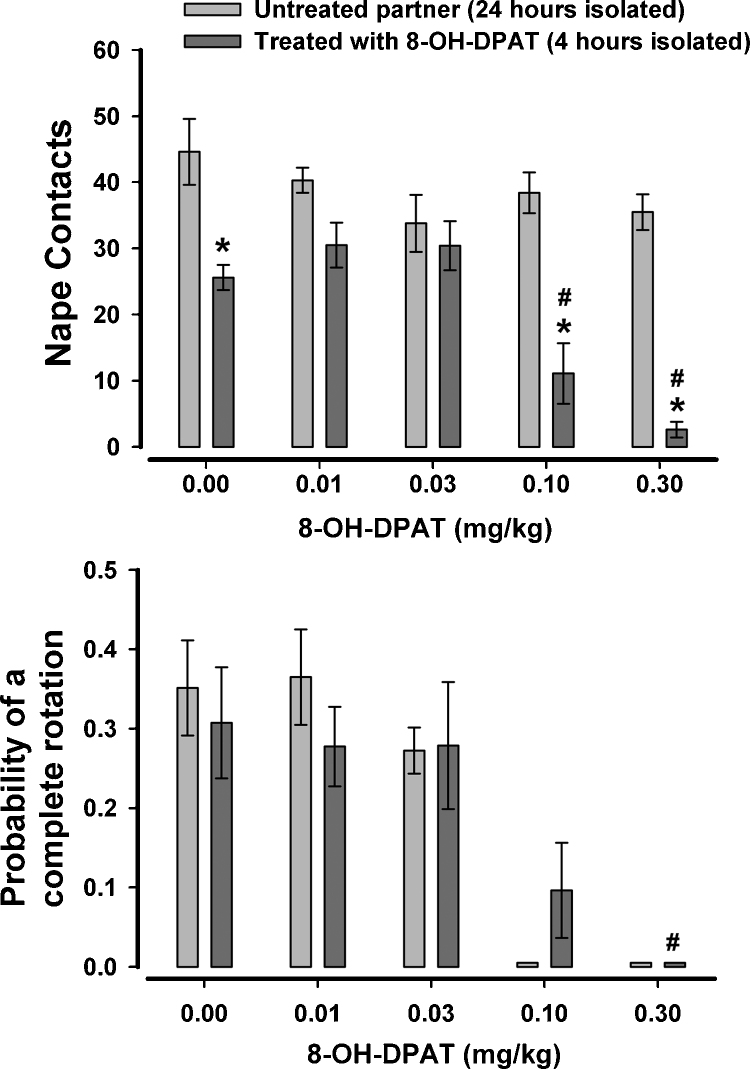

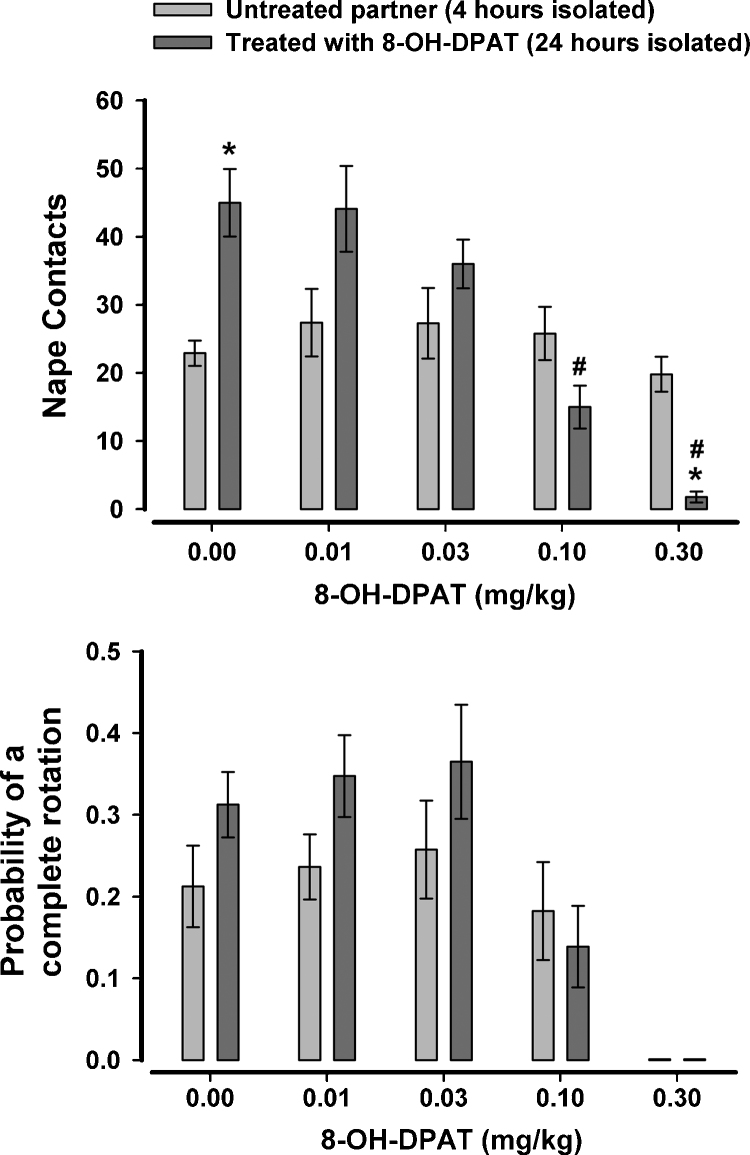

As can be seen in Fig. 5, Fig. 6, pairing a rat that has been isolated for 24 h with another rat that has been isolated for 4 h resulted in an asymmetry of nape contacts, with the rat isolated for 24 h accounting for more play solicitation than the rat isolated for only 4 h. When 8-OH-DPAT was given to the rat that was isolated for only 4 h (Fig. 5), there was found to be a significant effect of dose, F(4,56) = 7.97, p < .001, a significant effect of partner, F(1,14) = 126.03, p < .001, and a significant dose × partner interaction, F(1,14) = 5.75, p = .001. When nape contacts between untreated and treated partners were compared at each of the five doses, it was found that the treated rat had fewer nape contacts after vehicle and after the two higher doses of 8-OH-DPAT. There was no difference between the partners at the two lower doses, suggesting that the motivation-induced asymmetry in play solicitation collapsed when one of the rats (4 h isolated) was administered low autoreceptor-selective doses of 8-OH-DPAT. Several treated rats exhibited no nape contacts at the higher two doses of 8-OH-DPAT, making it impractical to compute the probability of a complete rotation for the untreated rats in these dyads. As a result, a full ANOVA was not done for responsiveness. Instead, the data from the vehicle and lower two doses were analyzed with a 2 × 3 ANOVA. There were no significant effects with this analysis. When just the data from the treated rat was analyzed using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA, there was found to be a significant effect of dose, F(4,28) = 7.56, p < .001, with the highest dose significantly reducing the probability of a complete rotation.

Fig. 5.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on nape contacts and the probability of responding to nape contacts with a complete rotation when only one rat of the test pair was treated. The rat treated with 8-OH-DPAT was isolated for 4 h prior to testing while the untreated partner was isolated for 24 h prior to testing. #p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg; *p < .05 when compared to untreated partner at the same dose level.

Fig. 6.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on nape contacts and the probability of responding to nape contacts with a complete rotation when only one rat of the test pair was treated. The rat treated with 8-OH-DPAT was isolated for 24 h prior to testing while the untreated partner was isolated for 4 h prior to testing. #p < .05 when compared to 0.0 mg/kg; *p < .05 when compared to untreated partner at the same dose level.

In order to see if the effect with 8-OH-DPAT was limited to a situation where the treated rat had a lower motivation to play, we also treated rats that were isolated for 24 h and allowed them to play with untreated rats that were isolated for only 4 h (Fig. 6). For nape contacts there was a significant effect of dose, F(4,56) = 14.51, p < .001 and a significant dose × partner interaction, F(4,56) = 9.71, p < .001. Further analysis of this interaction indicated that, as expected, the treated rat solicited more play after vehicle. However, as with the previous study, this difference collapsed after the two lower doses of 8-OH-DPAT. There was also no difference in nape contacts between the treated and untreated rat at 0.1 mg/kg but this dose also reduced nape contacts when compared to vehicle. The treated rat solicited less play than the untreated partner at the highest dose and this dose also reduced nape contacts compared to vehicle. Responsiveness to nape contacts were largely unaffected by either partner or dose. As with the preceding experiment, several treated rats exhibited no nape contacts at the highest dose of 8-OH-DPAT, making it impractical to compute the probability of a complete rotation for the untreated rats in these dyads. When a 2 × 4 ANOVA was done with the remaining 3 doses and vehicle, there was found to be a significant main effect of dose, F(3,42) = 4.19, p = .01, with the likelihood of responding with a complete rotation reduced at 0.1 mg/kg. When the data from the treated rats only were submitted to a one-way ANOVA, there was a significant effect of dose, F(4,28) = 21.58, p < .001, with the likelihood of responding to a nape contact with a complete rotation significantly reduced at 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg.

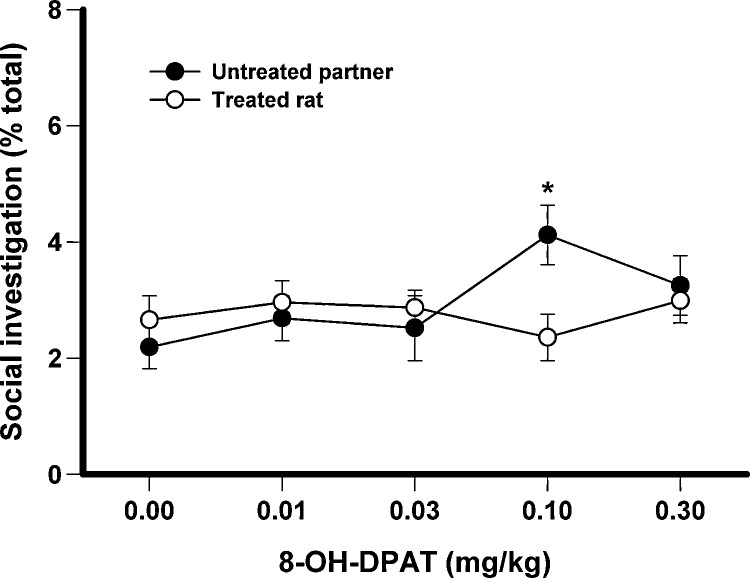

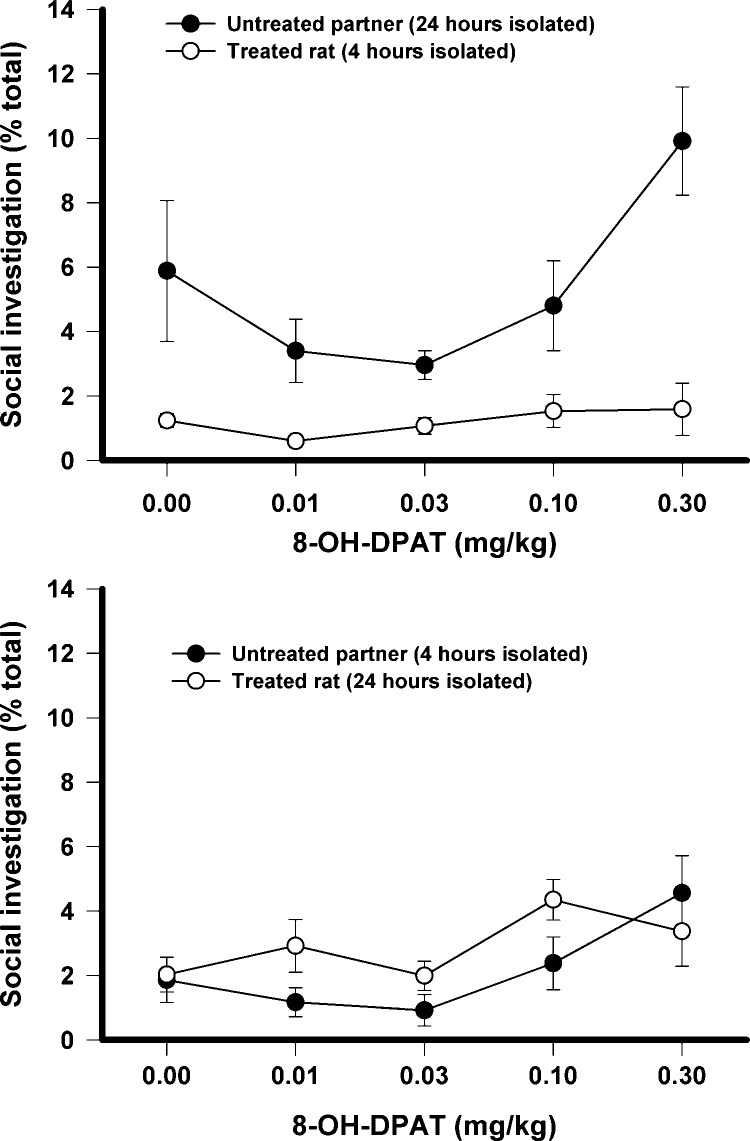

Social investigation in both the experiments is shown in Fig. 7. When given to a rat that was isolated for 4 h prior to testing (top panel), there was found to be a significant main effect of dose, F(4,56) = 3.98, p < .01, a significant main effect of partner, F(1,14) = 93.6, p < .001, and a significant dose × partner interaction, F(4,56) = 2.66, p < .05. While 8-OH-DPAT had no effect in the treated rats, analysis of the untreated partner showed that the highest dose differed from the other 3 doses, but not from the vehicle. When given to a rat that was isolated for 24 h prior to testing (bottom panel), there was a significant effect of dose, F(4,56) = 4.09, p < .01, with social investigation increasing after the highest dose.

Fig. 7.

The effects of 8-OH-DPAT on social investigation when only one rat of the test pair was treated. In the top panel the treated rat was isolated for 4 h prior to testing while the untreated partner was isolated for 24 h. In the bottom panel the treated rat was isolated for 24 h prior to testing while the untreated partner was isolated for 4 h prior to testing.

4. Discussion

Serotonin is pervasive throughout the brain and is known to be involved at some level in a wide variety of behaviors. Just on this basis alone, one would predict at least some role for serotonin in the modulation of play as well, although the specificity and direction of that modulation could still be open to speculation. While several studies have looked at serotonergic involvement in play, most of these have used manipulations that either up-regulate or down-regulate global serotonergic tone (Homberg et al., 2007, Knutson and Panksepp, 1997, Knutson et al., 1996, Taravosh-Lahn et al., 2006). From most of these early studies, it was concluded that increased activity in 5HT circuits decreases play and, by extension, that decreasing 5HT tone might be expected to facilitate playfulness. However, no studies have yielded significant increases in play following serotonergic down-regulation, although few of these studies assessed the effects of selective 5HT agonists and/or antagonists on play in rats.

There is an incredible diversity of serotonin receptor subtypes, although the 5HT1A receptor is the best characterized of these. 8-OH-DPAT is the prototypical 5HT1A agonist and has actions at both pre- and post-synaptic sites. It has been used extensively to study a variety of behavioral processes including feeding (Dourish et al., 1985, Hutson et al., 1986), aggression (Ferris et al., 1999, Haug et al., 1990, Muehlenkamp et al., 1995), sexual behavior (Rehman et al., 1999, Schnur et al., 1989) and social dominance (Bonson et al., 1994, Woodall et al., 1996), to name a few. At low doses 8-OH-DPAT is thought to bind preferentially to pre-synaptic auto-receptors, reducing firing of 5HT neurons in the raphe nuclei, thus decreasing levels of 5HT in forebrain target areas (Carboni and Di Chiara, 1989, Hjorth et al., 1982). So the behavioral effects of 8-OH-DPAT at low doses are often thought to be due to decreases in 5HT activity in forebrain areas, although effects due to activation of post-synaptic heteroreceptors cannot be discounted (De Vry, 1995).

Our initial interest in looking at the effects of 8-OH-DPAT began with the relatively straightforward hypothesis that an acute decrease in 5HT tone would increase play. As mentioned above, it is well established that play can be reliably reduced by acute increases of synaptic 5HT (Homberg et al., 2007, Knutson et al., 1996) and play among 5HT-transporter knockout rats is much lower than wild-type rats (Homberg et al., 2007). Play can also be reduced by the relatively non-selective 5HT receptor agonist quipazine, which is reversed by co-administration of the equally non-selective 5HT antagonist methysergide (Normansell and Panksepp, 1985b). By itself, methysergide only decreased play at higher doses. Doses of 8-OH-DPAT greater than or equal to 0.1 mg/kg reduced play in the present study as well and this would be consistent with the prevailing idea that enhanced activity at 5HT post-synaptic receptors reduces playfulness. These high-dose effects were also associated with decreases in locomotor activity (both distance traveled and velocity) and increases in social investigation. Given that social investigation also increased in untreated partners towards a treated partner (Fig. 7, top panel) it is likely that the increased sniffing at these higher doses may be the beneficiary of lower levels of playful activity being exhibited by the treated rat, perhaps increasing the likelihood of other social behaviors occurring, such as sniffing. This may be facilitated even further by a treated rat that is moving slower as well.

By using lower doses of 8-OH-DPAT that are known to decrease 5HT release, we believed that this would be a useful pharmacological tool for assessing effects of 5HT down-regulation on play. When tested in adult rats, low doses of 8-OH-DPAT have also been shown to increase social interactions when animals are made anxious, which is consistent with this class of compounds being used clinically as anxiolytics (Higgins et al., 1992, Olivier et al., 1991, Schreiber and DeVry, 1993, Shields and King, 2008). It was then reasoned that low autoreceptor-selective doses of 8-OH-DPAT may be expected to increase play in the rat. Initial results from our lab were promising, with doses in the 0.01–0.03 mg/kg range having a tendency to increase play (Siviy, 1998, Siviy et al., 1998). However, these increases in play were small and difficult to replicate. In our early studies and in the data shown in Fig. 1, both rats of the pair were treated similarly and in light of the work by Knutson and colleagues showing a more complex pattern of pharmacological effects when only one rat of the pair is treated (Knutson and Panksepp, 1997, Knutson et al., 1996) we chose to assess the effects of 8-OH-DPAT when only one rat of the testing pair was treated. When this was done in Experiment 1 the results were identical; no effect of 8-OH-DPAT on play was observed at low doses although decreases in both measures of play were still observed at higher doses.

In Experiment 1 both rats of the testing pair were isolated for 4 h prior to testing so the motivation to play was comparable between partners. This can be readily seen in Fig. 2, where nape contacts between the untreated and treated partner do not differ after vehicle. In Experiment 2 we then sought to determine whether 8-OH-DPAT would have a differential effect when an artificial asymmetry in play solicitation was established by varying the motivation to play between the partners. As expected, the partner that was isolated for 24 h accounted for more play solicitation (nape contacts) than the partner that was only isolated for 4 h prior to testing. Low doses of 8-OH-DPAT resulted in a collapse of this asymmetry such that there was no significant difference between the treated and untreated partner at 0.01 and 0.03 mg/kg. Most importantly, it did not matter whether the rat treated with 8-OH-DPAT was isolated for 24 h prior to testing, thus accounting for more nape contacts after vehicle, or was isolated for 4 h prior to testing and accounting for fewer nape contacts after vehicle. The net effect was for low doses of 8-OH-DPAT to decrease a pre-established asymmetry in play solicitation. Particularly interesting about this pattern of response is that the effect does not appear to be due solely to a change in behavior by the treated rat. Rather, there appear to be subtle changes in the behavior of both treated and untreated rats that combine to result in a lack of asymmetry.

While nape contacts were responsive to varying levels of motivation, the likelihood of responding to those contacts was not. Rats isolated for 24 h were no more likely to respond to nape contacts with a complete rotation than those isolated for 4 h. This is consistent with earlier reports showing that play solicitation and playful responsiveness are motivationally distinct aspects of play (Pellis and Pellis, 1991, Siviy et al., 1997). At low doses, 8-OH-DPAT had no effect on responsiveness. Although higher doses reduced the likelihood of responding with a complete rotation, these doses also reduced nape contacts and decreased overall activity so the behavioral specificity of effects at these doses is questionable. Knutson et al. (1996) also established an asymmetry in the play of two rats prior to treating one rat of the pair with fluoxetine but used pinning as an index for identifying a rat as either the dominant or subordinate member of the play dyad. In particular, the dominant rat was defined as the one which accounted for most of the pinning. In their study, treating the dominant rat with fluoxetine resulted in a collapse of the asymmetry in pinning activity such that after a few days of treatment the previously subordinate rat was pinning the dominant as often as the dominant pinned the subordinate. Interestingly, treating the subordinate had no effect on the pinning asymmetry. Furthermore, the collapse of asymmetry was largely due to increased pinning by the untreated and previously subordinate rat. These data show that prior social status can modulate the effects of fluoxetine on play and it was concluded by these investigators that treating the dominant partner of a play dyad with fluoxetine may enhance reciprocation by the subordinate partner. If we evaluate our own findings in this light, it suggests that serotonin may be broadly involved in how conspecifics interact with each other during playful encounters. Animals may then be particularly sensitive to serotonergic manipulations when there is some type of stable asymmetry between the participants. If that asymmetry is in the form of play solicitation, such as when one animal is more motivated to play than the other, then nape contacts are preferentially affected. On the other hand, if that asymmetry is in the form of responsiveness to these contacts, such as might be seen when social status factors into the play bouts, then responsiveness may be preferentially affected and the relative social status of the treated rat could determine whether any effect is observed.

There is already considerable evidence in the literature suggesting a modulatory influence of serotonin on how conspecifics interact with one another. However, much of this literature has focused on dominance and aggression. For example, aggression and dominance can be readily enhanced in crustaceans by increasing synaptic levels of serotonin (Huber et al., 1997, Huber et al., 2001) and changes in the dominance status of crustaceans can, in turn, alter the effects of serotonergic manipulations on subsequent behaviors (Yeh et al., 1996, Yeh et al., 1997). While increased aggression is consistent with increased dominance in a crayfish or lobster, the same cannot always be said for mammals where establishment of dominance can be a more nuanced affair. For example, Raleigh et al. (1991) looked at the effects of increasing or decreasing serotonergic tone on dominance among vervet monkeys. When the dominant male was removed from the group, thus producing instability among the remaining group members, and one of the remaining males was treated with either fluoxetine or tryptophan, the treated male showed less aggression towards the other males, showed more affiliative behavior towards the females, and acquired dominant status. Conversely, when serotonergic tone was reduced in one of the remaining males this resulted in a male that displayed more aggression towards the remaining males and less affiliative behavior. Increased affiliative behaviors in humans have also been reported after chronic treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors, along with decreased hostility and increased cooperation (Knutson et al., 1998a, Knutson et al., 1998b, Tse and Bond, 2002). Conversely, serotonin depletion in healthy humans can decrease cooperation in a prisoner's dilemma game (Wood et al., 2006). These data suggest that ambient levels of serotonin can have a subtle, but significant and consistent modulatory influence over how conspecifics interact with each other in dynamic social situations.

Returning to our own data, selective stimulation of 5HT1A receptors with low doses of 8-OH-DPAT seems to change the dynamic of a playful interaction between two participants that are differentially motivated to play. Play is a contagious behavior in the sense that high levels of playfulness by one rat can have a positive impact on the playfulness of another rat (Pellis and McKenna, 1992, Varlinskaya et al., 1999). A contagion effect would then need to reflect both an increased desire to play by the less playful partner along with willingness by the more playful partner to cede to that increased desire. In the present study, the net effect on playfulness of 8-OH-DPAT was essentially the same whether the more playful or less playful partner was treated. This suggests that activation of 5HT1A receptors may modulate how juvenile rats interpret and/or act on interactive cues that occur during playful encounters, perhaps making them more susceptible to a contagion effect.

Since 5HT1A receptors are present as both pre-synaptic autoreceptors and post-synaptic heteroreceptors, it cannot be easily determined from these experiments if the effects on play reflect either decreased or increased serotonin activity. It has even been argued that because of the complexity of the serotonin system in general and the 5HT1A system in particular, it may be difficult to predict exact effects associated with specific doses of systemically administered 8-OH-DPAT or any other 5HT1A agonist for that matter (De Vry, 1995). With this caveat in mind, however, we can still begin with the assumption that the lower doses of 8-OH-DPAT used in this study (0.01–0.03 mg/kg) are most likely acting at autoreceptors to reduce firing of serotonin neurons in the raphé nuclei, resulting in an acute decrease in forebrain levels of serotonin. When these data are then viewed in a broader context of serotonergic functioning we can begin piecing together a working hypothesis on how serotonin may be involved in juvenile playfulness. For example, it has recently been posited that increased serotonin neurotransmission may favor the expression of those types of social behaviors that are associated with low levels of arousal (Tops et al., 2009). Since play is a highly arousing activity, this conceptualization would be consistent with the hypothesis described earlier that low levels of serotonin would tend to facilitate playfulness. Low levels of serotonin are also known to result in behavioral disinhibition and, in this context, it has been suggested that increased serotonin neurotransmission leads to motivational processes opposite to those mediated by dopamine (Cools et al., 2007). Given that play seems to be associated with increased release of dopamine (Robinson et al., 2011, Trezza et al., 2010) an acute reduction in serotonin levels may then modulate play through subtle interactions with brain dopamine systems.

It is hoped that hypotheses such as these can be more vigorously addressed using methods to target specific subpopulations of 5HT receptors. For example, a recent study reported a novel means to independently manipulate 5HT1A autoreceptors and heteroreceptors in mice (Richardson-Jones et al., 2011), allowing these authors to demonstrate that 5HT1A involvement in anxiety is a developmental process involving autoreceptors, but not heteroreceptors. As comparable models become more readily available for the rat (Hamra, 2010, Tong et al., 2010), studies such as these that can target subpopulations of 5HT1A receptors in the more social rat may become possible. In the meantime, further studies using behavioral models such as those described in this paper and those used by Knutson et al. (1996), when combined with a pharmacological toolbox that includes drugs with varying degrees of specificity for autoreceptors and heteroreceptors (de Boer and Koolhaas, 2005), may yield significant insights into the role that serotonin may have in the modulation of juvenile playfulness.

References

- Beatty W.W., Costello K.B., Berry S.L. Suppression of play fighting by amphetamine: effects of catecholamine antagonists, agonists and synthesis inhibitors. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1984;20:747–755. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty W.W., Dodge A.M., Dodge L.J., White K., Panksepp J. Psychomotor stimulants, social deprivation and play in juvenile rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1982;16:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard D.C., Griebel G., Rodgers R.J., Blanchard R.J. Benzodiazepine and serotonergic modulation of antipredator and conspecific defense. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1998;22(5):597–612. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonson K.R., Johnson R.G., Fiorella D., Rabin R.A., Winter J.C. Serotonergic control of androgen-induced dominance. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;49:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli S.A., Nie R., Whipple C., Winiger V., Hofer M.A., Zimmerberg B. The effects of selective breeding for infant ultrasonic vocalizations on play behavior in juvenile rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;87:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J., Knutson B., Panksepp J. Anticipation of rewarding electrical brain stimulation evokes ultrasonic vocalization in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J., Knutson B., Panksepp J., Ikemoto S. Nucleus accumbens amphetamine microinjections unconditionally elicit 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:940–944. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J., Kroes R.A., Moskal J.R., Pfaus J.G., Brudzynski S.M., Panksepp J. Ultrasonic vocalizations of rats (Rattus norvegicus) during mating, play, and aggression: behavioral concomitants, relationship to reward, and self-administration of playback. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2008;122(4):357–367. doi: 10.1037/a0012889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J., Panksepp J. Tickling induces reward in adolescent rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2001;72:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt G.M. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits. [Google Scholar]

- Calcagnetti D.J., Schechter M.D. Place conditioning reveals the rewarding aspect of social interaction in juvenile rats. Physiology and Behavior. 1992;51:667–672. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E., Di Chiara G. Serotonin release estimated by transcortical dialysis in freely-moving rats. Neuroscience. 1989;32:637–645. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R., Roberts A.C., Robbins T.W. Serotoninergic regulation of emotional and behavioural control processes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;12:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P., Huys Q.J.M. Serotonin in affective control. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32(1):95–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer S.F., Koolhaas J.M. 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists and aggression: a pharmacological challenge of the serotonin deficiency hypothesis. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2005;526(1-3):125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J. 5-HT1A receptor agonists: recent developments and controversial issues. Psychopharmacology. 1995;121(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02245588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas L.A., Varlinskaya E.I., Spear L.P. Rewarding properties of social interactions in adolescent and adult male and female rats: impact of social versus isolate housing of subjects and partners. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45(3):153–162. doi: 10.1002/dev.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourish C.T., Hutson P.H., Curzon G. Low doses of the putative serotonin agonist 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) elicit feeding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1985;86:197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00431709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagen R. Oxford University Press; New York: 1981. Animal Play Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S.A., Cada A.M. Spatial learning/memory and social and nonsocial behaviors in the spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto and Sprague-Dawley rat strains. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2004;77(3):583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris C.F., Stolberg T., Delville Y. Serotonin regulation of aggressive behavior in male golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Behavioral Neuroscience. 1999;113:804–815. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field E.F., Pellis S.M. Differential effects of amphetamine on the attack and defense components of play fighting in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 1994;56:325–330. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff F.G. On serotonin and experimental anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163(3–4):467–476. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamra F.K. Enter the rat. Nature. 2010;467:161–163. doi: 10.1038/467161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A.R., Holmes A. Genetics of emotional regulation: the role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug M., Wallian L., Brain P.F. Effects of 8-OH-DPAT and fluoxetine on activity and attack by female mice towards lactating intruders. General Pharmacology. 1990;21:845–849. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(90)90443-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins G.A., Jones B.J., Oakley N.R. Effect of 5-HT1A receptor agonists in two models of anxiety after dorsal raphe injection. Psychopharmacology. 1992;106:261–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02801982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth S., Carlsson A., Lindberg P., Sanchez D., Wikstrom H., Arvidsson L.-E. 8-Hydroxy-2-(Di-n-propylamino)tetralin, 8-OH-DPAT, a potent and selective simplified ergot congener with central 5-HT-receptor stimulating activity. Journal of Neural Transmission. 1982;55:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Homberg J.R., Schiepers O.J.G., Schoffelmeer A.N.M., Cuppen E., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Acute and constitutive increases in central serotonin levels reduce social play behaviour in peri-adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;195:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0895-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R., Orzeszyna M., Pokorny N., Kravitz E.A. Biogenic amines and aggression: experimental approaches in crustaceans. Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 1997;50(Suppl. 1):60–68. doi: 10.1159/000113355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R., Panksepp J.B., Yue Z., Delago A., Moore P. Dynamic interactions of behavior and amine neurochemistry in acquisition and maintenance of social rank in crayfish. Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 2001;57(5):271–282. doi: 10.1159/000047245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys A.P., Einon D.R. Play as a reinforcer for maze-learning in juvenile rats. Animal Behavior. 1981;29:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hutson P.H., Dourish C.T., Curzon G. Neurochemical and behavioural evidence for mediation of the hyperphagic action of 8-OH-DPAT by 5-HT cell body autoreceptors. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1986;129:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B., Burgdorf J., Panksepp J. Anticipation of play elicits high-frequency ultrasonic vocalizations in young rats. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1998;112:65–73. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B., Burgdorf J., Panksepp J. High-frequency ultrasonic vocalizations index conditioned pharmacological reward in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 1999;66:639–643. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B., Panksepp J. Effects of serotonin depletion on the play of juvenile rats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;807:475–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B., Panksepp J., Pruitt D. Effects of fluoxetine on play dominance in juvenile rats. Aggressive Behavior. 1996;22:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B., Wolkowitz O.M., Cole S.W., Chan T., Moore E.A., Johnson R.C. Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:371–379. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G.R., Humphrey P.P.A. Receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine: current perspectives on classification and nomenclature. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:261–273. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh T.K., Barfield R.J. The temporal patterning of 40–60 kHz ultrasonic vocalizations and copulation in the rat (Rattus norvegicus) Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1980;29:349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Meaney M.J., Stewart J. A descriptive study of social development in the rat (Rattus norvegicus) Animal Behaviour. 1981;29:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Millan M.J., Marin P., Bockaert J., Mannoury la Cour C. Signaling at G-protein-coupled serotonin receptors: recent advances and future research directions. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2008;29(9):454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp F., Lucion A., Vogel W.H. Effects of selective serotonergic agonists on aggressive behavior in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1995;50:671–674. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesink R.J.M., Van Ree J.M. Involvement of opioid and dopaminergic systems in isolation-induced pinning and social grooming of young rats. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normansell L., Panksepp J. Effects of clonidine and yohimbine on the social play of juvenile rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1985;22(5):881–883. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normansell L., Panksepp J. Effects of quipazine and methysergide on play in juvenile rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1985;22:885–887. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normansell L., Panksepp J. Effects of morphine and naloxone on play-rewarded spatial discrimination in juvenile rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1990;23:75–83. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier B., Tulp M.T.M., Mos J. Serotonergic receptors in anxiety and aggression: evidence from animal pharmacology. Human Psychopharmacology. 1991;6:S73–S78. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. The ontogeny of play in rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1981;14:327–332. doi: 10.1002/dev.420140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. Rough and tumble play: a fundamental brain process. In: MacDonald K., editor. Parent–Child Play. SUNY Press; Albany: 1993. pp. 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Beatty W.W. Social deprivation and play in rats. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1980;30:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)91077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Bishop P. An autoradiographic map of [3H]diprenorphine binding in rat brain: effects of social interaction. Brain Research Bulletin. 1981;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(81)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Jalowiec J., DeEskinazi F.G., Bishop P. Opiates and play dominance in juvenile rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1985;99:441–453. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Siviy S.M., Normansell L. The psychobiology of play: theoretical and methodological considerations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1984;8:465–492. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M., Casteneda E., McKenna M.M., Tran-Nguyen L.T., Whishaw I.Q. The role of the striatum in organizing sequences of play fighting in neonatally dopamine-depleted rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;158:13–15. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90600-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M., McKenna M.M. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on play fighting in rats: effects of dominance, partner's playfulness, temperament and neonatal exposure to testosterone propionate. Behavioural Brain Research. 1992;50:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M., Pellis V.C. Attack and defense during play fighting appear to be motivationally independent behaviors in muroid rodents. The Psychological Record. 1991;41:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M., Pellis V.C. Oneworld Publications; Oxford: 2009. The Playful Brain: Venturing to the Limits of Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M., Pellis V.M. Play-fighting differs from serious fighting in both target of attack and tactics of fighting in the laboratory rat Rattus norvegicus. Aggressive Behavior. 1987;13:227–252. [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh M.J., McGuire M.T., Brammer G.L., Pollack D.B., Yuwiler A. Serotonergic mechanisms promote dominance acquisition in adult male vervet monkeys. Brain Research. 1991;559:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90001-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman J., Kaynan A., Christ G., Valcic M., Maayani S., Melman A. Modification of sexual behavior of Long–Evans male rats by drugs acting on the 5-HT1A receptor. Brain Research. 1999;821:414–425. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart C.J., McIntyre D.C., Metz G.A., Pellis S.M. Play fighting between kindling-prone (FAST) and kindling-resistant (SLOW) rats. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2006;120:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart C.J., Pellis S.M., McIntyre D.C. Development of play fighting in kindling-prone (FAST) and kindling-resistant (SLOW) rats: how does the retention of phenotypic juvenility affect the complexity of play? Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45(2):83–92. doi: 10.1002/dev.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Jones J.W., Craige C.P., Nguyen T.H., Kung H.F., Gardier A.M., Dranovsky A. Serotonin-1A autoreceptors are necessary and sufficient for the normal formation of circuits underlying innate anxiety. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(16):6008–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5836-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D.L., Zitzman D.L., Smith K.J., Spear L.P. Fast dopamine release events in the nucleus accumbens of early adolescent rats. Neuroscience. 2011;176:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnur S.L., Smith E.R., Lee R.L., Mas M., Davidson J.M. A component analysis of the effects of DPAT on male rat sexual behavior. Physiology and Behavior. 1989;45:897–901. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R., DeVry J. Neuronal circuits involved in the anxiolytic effects of the 5-HT1A receptor agonists 8-OH-DPAT, ipsapirone and buspirone in the rat. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;249:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90531-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp T., Boothman L., Raley J., Quérée P. Important messages in the post: recent discoveries in 5-HT neurone feedback control. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2007;28(12):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields J., King J.A. The role of 5HT1A receptors in the behavioral responses associated with innate fear. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122:611–617. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M. Neurobiological substrates of play behavior: glimpses into the structure and function of mammalian playfulness. In: Bekoff M., Byers J.A., editors. Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative, and Ecological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Atrens D.M. The energetic costs of rough-and-tumble play in the juvenile rat. Developmental Psychobiology. 1992;25:137–148. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Atrens D.M., Menendez J.A. Idazoxan increases rough-and-tumble play, activity and exploration in juvenile rats. Psychopharmacology. 1990;100:119–123. doi: 10.1007/BF02245801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Baliko C.N. A further characterization of alpha-2 adrenoceptor involvement in the rough-and-tumble play of juvenile rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;37:24–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(200007)37:1<25::aid-dev4>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Baliko C.N., Bowers K.S. Rough-and-tumble play behavior in Fischer-344 and Buffalo rats: effects of social isolation. Physiology and Behavior. 1997;61:597–602. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Boustani M., Birkholz J.H., Pineault M. Serotonergic involvement in the rough-and-tumble play of juvenile rats. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998;24:1922–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Crawford C.A., Akopian G., Walsh J.P. Dysfunctional play and dopamine physiology in the Fischer 344 rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2011;220:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Fleischhauer A.E., Kerrigan L.A., Kuhlman S.J. D2 dopamine receptor involvement in the rough-and-tumble play behavior of juvenile rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1996;110:1–9. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.5.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Fleischhauer A.E., Kuhlman S.J., Atrens D.M. Effects of alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonists on rough-and-tumble play in juvenile rats: evidence for a site of action independent of non-adrenoceptor imidazoline binding sites. Psychopharmacology. 1994;113:493–499. doi: 10.1007/BF02245229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Love N.J., DeCicco B.M., Giordano S.B., Seifert T.L. The relative playfulness of juvenile Lewis and Fischer-344 rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2003;80:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siviy S.M., Panksepp J. Sensory modulation of juvenile play in rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1987;20:39–55. doi: 10.1002/dev.420200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W.S. Notes on the psychic development of the young white rat. The American Journal of Psychology. 1899;11(1):80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Taravosh-Lahn K., Bastida C., Delville Y. Differential responsiveness to fluoxetine during puberty. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:1084–1092. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E., Alberts J.R., Cramer C.P. Weaning in rats: II. Pup behavior patterns. Developmental Psychobiology. 1990;23:495–510. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C., Li P., Wu N.L., Yan Y., Ying Q.-L. Production of p53 gene knockout rats by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells [10.1038/nature09368] Nature. 2010;467(7312):211–213. doi: 10.1038/nature09368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops M., Russo S., Boksem M.A.S., Tucker D.M. Serotonin: modulator of a drive to withdraw. Brain and Cognition. 2009;71(3):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Baarendse P.J.J., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Prosocial effects of nicotine and ethanol in adolescent rats through partially dissociable neurobehavioral mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2560–2573. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Baarendse P.J.J., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2010;31:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Damsteegt R., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Conditioned place preference induced by social play behavior: parametrics, extinction, reinstatement and disruption by methylphenidate. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Bidirectional cannabinoid modulation of social behavior in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Cannabinoid and opioid modulation of social play behavior in adolescent rats: differential behavioral mechanisms. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;18:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V., Vanderschuren L.J.M.J. Divergent effects of anandamide transporter inhibitors with different target selectivity on social play behavior in adolescent rats. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2009;328:343–350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse W.S., Bond A.J. Serotonergic intervention affects both social dominance and affiliative behaviour. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:324–330. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Niesink R.J.M., Spruijt B.M., Van Ree J.M. μ- and κ-opioid receptor-mediated opioid effects on social play in juvenile rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;276:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00040-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Niesink R.J.M., Spruijt B.M., Van Ree J.M. Effects of morphine on different aspects of social play in juvenile rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995;117:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02245191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Niesink R.J.M., Van Ree J.M. The neurobiology of social play behavior in rats. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1997;21:3090–3326. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Spruijt B.M., Hol T., Niesink R.J.M., Van Ree J.M. Sequential analysis of social play behavior in juvenile rats: effects of morphine. Behavioural Brain Research. 1996;72:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Stein E.A., Wiegant V.M., Van Ree J.M. Social play alters regional brain opioid receptor binding in juvenile rats. Brain Research. 1995;680:148–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00256-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L.J.M.J., Trezza V., Griffioen-Roose S., Schiepers O.J.G., Van Leeuwen N., De Vries T.J. Methylphenidate disrupts social play behavior in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2946–2956. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya E.I., Spear L.P., Spear N.E. Social behavior and social motivation in adolescent rats: role of housing conditions and partner's activity. Physiology and Behavior. 1999;67:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R.M., Rilling J.K., Sanfey A.G., Bhagwagar Z., Rogers R.D. Effects of tryptophan depletion on the performance of an iterated prisoner's dilemma game in healthy adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(5):1075–1084. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall K.L., Domeney A.M., Kelly M.E. Selective effects of 8-OH-DPAT on social competition in the rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1996;54:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh S.-R., Fricke R.A., Edwards D.H. The effect of social experience on serotonergic modulation of the escape circuit of crayfish. Science. 1996;271:366–369. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh S.-R., Musolf B.E., Edwards D.H. Neuronal adaptations to changes in the social dominance status of crayfish. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:697–708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00697.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]