Abstract

Background: Many patients with serious kidney disease have an elevated symptom burden, high mortality, and poor quality of life. Palliative care has the potential to address these problems, yet nephrology patients frequently lack access to this specialty.

Objectives: We describe patient demographics and clinical activities of the first 13 months of an ambulatory kidney palliative care (KPC) program that is integrated within a nephrology practice.

Design/Measurements: Utilizing chart abstractions, we characterize the clinic population served, clinical service utilization, visit activities, and symptom burden as assessed using the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale-Renal (IPOS-R), and patient satisfaction.

Results: Among the 55 patients served, mean patient age was 72.0 years (standard deviation [SD] = 16.7), 95% had chronic kidney disease stage IV or V, and 46% had a Charlson Comorbidity Index >8. The mean IPOS-R score at initial visit was 16 (range = 0–60; SD = 9.1), with a mean of 7.5 (SD = 3.7) individual physical symptoms (range = 0–15) per patient. Eighty-seven percent of initial visits included an advance care planning conversation, 55.4% included a medication change for symptoms, and 35.5% included a dialysis decision-making conversation. Overall, 96% of patients who returned satisfaction surveys were satisfied with the care they received and viewed the KPC program positively.

Conclusions: A model of care that integrates palliative care with nephrology care in the ambulatory setting serves high-risk patients with serious kidney disease. This KPC program can potentially meet documented gaps in care while achieving patient satisfaction. Early findings from this program evaluation indicate opportunities for enhanced patient-centered palliative nephrology care.

Keywords: ambulatory palliative care, kidney disease, nephrology, palliative care, symptom burden

Introduction

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) have increased symptoms and experience high health care utilization that often is not goal concordant, particularly at the end of life.1–3 Consequently, this population commonly faces complex medical decisions, including whether to initiate or to withdraw dialysis. To optimize care, nephrology professional societies recommend shared decision-making and incorporation of quality-of-life considerations in clinical decisions.4–7 Despite these recommendations, the ideal model for delivery of such patient-centered care is unknown and shared decision making remains poorly integrated into routine nephrology care. This gap has profound clinical consequences as patients report regret about initiating dialysis and a decision-making process that lacks discussion of nondialysis (conservative) management of kidney disease.8,9 Incorporation of palliative care into nephrology care may potentially address these gaps, particularly early in the disease course. Research has demonstrated benefits of palliative care for heart failure and cancer, yet evidence is limited for kidney disease.10,11

We previously described a conceptual model for an ambulatory kidney palliative care (KPC) program embedded within a nephrology practice.12 That model, and an Australian KPC model13 serve as the framework for our program, Kidney CARES (Comprehensive Advanced Renal disease and End-stage renal disease Support). Herein, we describe our first evaluation assessing this program's ability to: (1) engage and retain patients with serious kidney disease, (2) address palliative care needs specific to CKD, and (3) assess patients' experience.

Methods

Program description and setting

The KPC team conducts patient visits one half-day per week. The team consists of a doctor trained in palliative care and nephrology and a palliative care psychologist. Nephrologists, hospitalists, and dialysis centers refer to the clinic; patients also self-refer. Although the program is designed for patients with serious kidney disease (Table 1), those at any stage of disease can receive care.

Table 1.

Target Population for Referral to the Kidney Palliative Care Program

| (1) Any patient receiving or recently started on renal replacement therapy |

| (2) Any patient with advanced kidney disease experiencing severe physical symptoms, emotional distress, or multiple hospitalizations |

| (3) Any patient who is considering dialysis withdrawal |

| (4) Any patient older than 65 years with CKD stage IV or V |

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation consists of a history focusing on KPC needs (Table 2), determination of comorbidity burden (Charlson comorbidity index [CCI] calculated through chart review), and functional status. In dialysis patients, CCI ≥8 is associated with approximately 50% one-year mortality.14 We assessed functional status using the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) Scale. The KPS ranges from 0 to 100 (%), with 100 representing normal activity and lower scores representing decreased function.15 Increased mortality has been described at scores ≤80 (normal activity with effort) in CKD patients and ≤70 (able to care for oneself, but unable to carry on normal activity or do active work) for those on dialysis.16,17

Table 2.

Components of an Outpatient Kidney Palliative Care Visit

| Building rapport |

| Assessing patients understanding of his or her disease |

| Determining coping mechanisms, including support networks |

| Attaining how the patient would best like to receive information |

| Assessing how the patient defines their quality of life |

| Physical and emotional symptom burden |

| Spiritual well being |

| Caregiver support |

| Assessing functional status |

| Discussions of prognosis if appropriate |

| Dialysis decision making if appropriate |

| Goals of renal replacement |

| Understanding of conservative management of kidney disease |

| Understanding of options of dialysis withdrawala |

| Advance care planning if appropriate |

If appropriate.

Source: Modified from Yoong et al.19

We measured symptom burden at each visit with the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale-Renal (IPOS-R) survey.18 Using this instrument, based on a scale of 0–4 (0 = no affect; 4 = overwhelming affect), patients rate the impact over the past week of 15 physical symptoms, with separate questions on emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression). The symptom score is the sum of individual physical symptoms scored one or greater, range 0–15. Total symptom burden was calculated by adding the severity of physical symptoms, range 0–60.

Data collection

We conducted a chart review of visits from May 6, 2016 to July 1, 2017. Chart abstraction included demographics, symptom burden, and application of a modified established framework for ambulatory palliative care to categorize visit activities.19

All data were recorded, de-identified, and stored on a secure, password-protected server using REDCap software.20 Excel and R were used for all analyses.

Visit activities

We (K.H. and J.F.) reviewed all progress notes and recorded visit activities using the following categories19: (1) addressing symptoms; (2) establishing illness understanding, information preference, and prognostic awareness; (3) addressing coping; (4) dialysis decision making, including discussions of time-limited trials and dialysis withdrawal; and (5) advance care planning (ACP).

We confirmed assigned categories using a 20% random sample blinded to original categorization; agreement between all reviewers concerning categorization was 95%.

Patient satisfaction

We assessed patient satisfaction through an anonymous survey adapted from the University of California-San Francisco Symptom Management Service given at the end of the patient's first visit (Supplementary Data). We asked patients about their visit, including how important it was that KPC services were offered (response was a scale of 1–5, 1 = very unimportant, 5 = very important).21

The New York University Investigational Review Board determined this study to be exempt from review.

Results

Clinic utilization

We evaluated 55 unique patients who completed 113 visits over the 13-month period of observation. Twenty-six (47%) patients had follow-up visits (range = 1–7). There were 31 (13%) no shows, and 104 (42%) cancellations, with 35 (37%) rescheduled within the first 13 months. Excluding calls returned for medication refills, 29 individual (range per patient 0–9) telephone encounters were documented during the period of observation.

Patient demographics

Thirty patients (55%) were men. Mean age was 72.8 (standard deviation [SD] = 16.6, range = 26–98), with 52 (95%) patients having stage IV or V CKD (Table 3). Twenty-three (42%) patients were on renal replacement therapy, whereas 14 (25%) had chosen conservative management. The mean CCI was 7.3 (SD = 3.4), range = 2–17, with 25 (45%) having an index ≥8. Mean KPS score was 57.7% (SD = 20.2, range = 20–100). A majority (n = 37, 67%) had scores of ≤70%. Fourteen (25%) listed a language other than English as their first language. Eight (57%) utilized hospital interpreter resources during visits.

Table 3.

Patient Demographics, n = 55

| Age (mean) years (SD), range | 72.0 (16.7), 26–98 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 30 (55) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 25 (45) |

| Black or African American | 12 (22) |

| Asian | 6 (11) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 12 (22) |

| CKD stage, n (%) | |

| Stage II or III | 3 (5) |

| Stage IV | 6 (11) |

| Stage V | 46 (84) |

| Therapy choice, n (%) | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 23 (42) |

| Conservative management | 14 (25) |

| Deciding | 11 (20) |

| Plan for renal replacement therapy | 4 (7) |

| Neither | 3 (5) |

| CCI score, n (%) | |

| x ≤ 5 | 14 (25) |

| 5 < x ≤ 8 | 16 (29) |

| 8 < x ≤ 17 | 25 (46) |

| Karnofsky Performance Score, mean (SD), range | 57.7 (20.2), 20–100 |

| Number of symptoms, mean (SD) | 7.5 (3.7) |

| Symptom burden, mean (SD) | 16.1 (9.1) |

| Number of follow-up visits, n (%) | |

| 1 | 29 (53) |

| 2 | 26 (25) |

| 3–4 | 7 (13) |

| 5+ | 5 (9) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; SD, standard deviation.

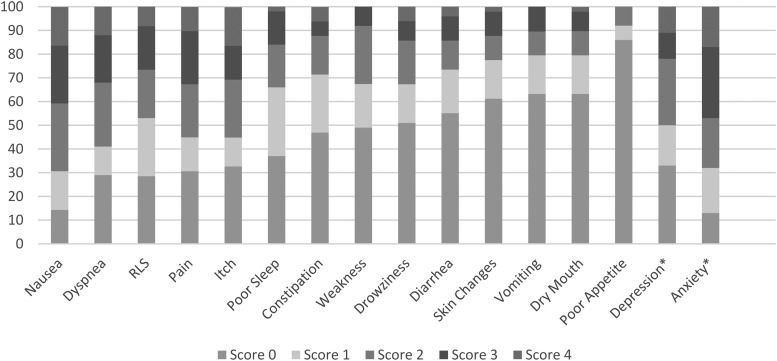

Symptom burden

Forty-nine patients (89%) completed the IPOS-R survey on their first visit. Figure 1 shows the prevalence and severity of each symptom. The mean global physical burden score was 16 of a possible 60 (SD = 9.2, range = 1–34), with the mean number of symptoms being 8 of 15 (SD = 3.4, range = 0–14). Twenty-one patients (44%) rated three or more symptoms as very bothersome or overwhelmingly bothersome. The most prevalent recorded emotional symptom was disease-related anxiety or worry, reported in 87% of patients. Sixty-seven percent of patients who responded reported depression (n = 12 of 18 responses).

FIG. 1.

Symptom prevalence at initial visit (n = 49). *n = 18 for depression, n = 47 for anxiety question, RLS, Restless Legs Syndrome.

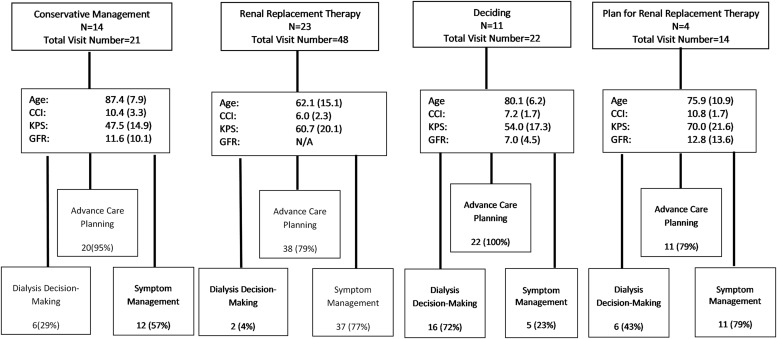

Visit activities

Forty-eight (87.3%) of the 55 initial clinic visits included an ACP conversation, 30 (55.4%) included symptom management, 52 (95.4%) addressed coping with disease, and 19 (35.5%) included a dialysis decision-making conversation (Table 4). Figure 2 gives a break down of visit activities from all clinic visits into three broad categories (ACP, symptom management, and dialysis decision making) and organized by treatment choice. Almost all visits (95%–100%) for patients deciding about treatment, or on conservative management, included an ACP conversation. Patients on dialysis required symptom management in 77% of their visits compared with 49% for those not on dialysis.

Table 4.

Breakdown of Initial Visit Activities

| Breakdown of visit activities | |

|---|---|

| Visit activity, n (%) | Initial visit, n = 55 |

| Advance care planning | 48 (87) |

| Symptom management | 30 (55) |

| Coping with disease | 52 (95) |

| Dialysis decision making | 19 (36) |

| Prognostic awareness | 15 (27) |

| Information preference | 6 (11) |

FIG. 2.

Visit activities by treatment choice. Age: mean years (SD); CCI: mean (SD); KPS: % (SD); GFR: mL/minute/1.73 m2, mean (SD). CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; SD, standard deviation.

Patient satisfaction

Twenty-seven patients (49%) returned surveys. Twenty-six (96%) rated the clinic services at 5 (very important) versus 4% at 4 of 5.

Discussion

We present data from an ambulatory KPC clinic and demonstrate that it achieved its early goals. Kidney CARES reached its target population, those with serious kidney disease, and delivered nephrology-specific palliative care that addressed documented gaps in care. For example, previous research showed that this population views symptom management as a top priority in their care, yet research shows symptoms often are under-recognized and undertreated.22,23 Accordingly, our patients reported a significant emotional (anxiety, depression, and worry) and physical (44%) symptom burden. Appropriately, a large number (55%) of visits offered symptom management. Our program also shows promise in caring for patients who choose conservative management (25% of the population), an under-reported population of patients.

The KPC team conducted ACP conversations in 87% of initial visits. These conversations are integral in the care of serious illness, yet studies cite that kidney disease patients have advance care directives documented 11%–20% lower than those with other serious illness.3,24 In this preliminary report, given the high rate of provision of ACP and the documented need, we hypothesize that an ambulatory KPC is a setting poised to address this issue. It is notable that 25% of our patients were non-native English speakers. As the program grows, it will be essential to consider how to achieve effective and culturally sensitive communication with non-English speaking patients facing complex decisions.

Our no-show rate of 13% is lower than what was reported in the literature for outpatient palliative care.25 Our 48% retention rate may reflect more advanced illness reducing follow-up, but further evaluation is needed. In addition, given that telephone communications were frequent, future expansion of the clinical services should consider use of telemedicine and home visits. Lastly, our postvisit survey data show that patients had a positive view of their experience. In aggregate, these findings suggest opportunities for sustainability and growth.

Limitations

This is a single-center program staffed by a practicing nephrologist and palliative care doctor, limiting generalizability. Although we were able to identify key elements of palliative care through chart review, we could not evaluate the effectiveness of shared decision making and symptom management, or documentation of advance directives in this initial evaluation.

Conclusions and Future Steps

To our knowledge, this is the first report on an ambulatory KPC program in the United States. These findings provide much promise for delivering effective nephrology palliative care. Future development will focus on inclusion of social work services and spiritual care. We plan for a rigorous evaluation of an expanded clinical model to guide improvements, ensure financial sustainability, and to optimize patient-centered care for those with advanced kidney disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Cambia Health Foundation and the MSTAR Program (Grant No. 5T35AG050998-04) in the funding of this work. The authors would also like to acknowledge Stephen P. Wall, MD, MSc, MAEd and Rebecca Wright, PhD, BSc (Hons), RN for their contributions to the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors have no conflict of interest that would influence this article.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ: The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2007;14:82–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States Renal Data System: 2018 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong SP, Kreuter W, O'Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:661–663; discussion 663–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tamura MK, Meier DE: Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1783–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al. : Critical and honest conversations: The evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:1664–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Renal Physicians Association: Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, et al. : Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 2015;88:447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:195–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, et al. : Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2815–2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 20103;63:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. : Palliative care in heart failure: The PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:331–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scherer JS, Wright R, Blaum CS, Wall SP: Building an outpatient kidney palliative care clinical program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:108.e2–116.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Josland E, Brennan F, Anastasiou A, Brown MA: Developing and sustaining a renal supportive care service for people with end-stage kidney disease. Ren Soc Australas J 2012;8:12–18 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, et al. : A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med 2000;108:609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karnofsky performance status scale definitions rating (%) criteria. www.hospicepatients.org/karnofsky.html (Last accessed May10, 2019)

- 16. Ifudu O, Paul HR, Homel P, Friedman EA: Predictive value of functional status for mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol 1998;18:109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ritchie JP, Alderson H, Green D, et al. : Functional status and mortality in chronic kidney disease: Results from a prospective observational study. Nephron Clin Pract 2014;128:22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palliative Care Outcome Scale: Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale-Renal. https://pos-pal.org/maix/ipos-renal-in-english.php (Last accessed May10, 2019)

- 19. Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. : Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. : Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. University of California San Fransisco Symptom Management Service. http://cancer.ucsf.edu/support/sms (Last accessed June29, 2019)

- 22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Carter SM, et al. : Patients' priorities for health research: Focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:3206–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, et al. : Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:960–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, et al. : Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1095–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aggarwal SK, Ghosh A, Cheng MJ, et al. : Initiating pain and palliative care outpatient services for the suburban underserved in Montgomery County, Maryland: Lessons learned at the NIH Clinical Center and MobileMed. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.