Abstract

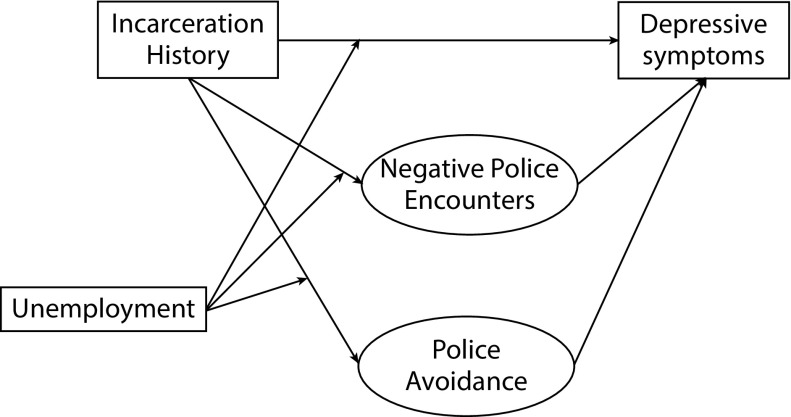

Objectives. To examine negative police encounters and police avoidance as mediators of incarceration history and depressive symptoms among US Black men and to assess the role of unemployment as a moderator of these associations.

Methods. Data were derived from the quantitative phase of Menhood, a 2015–2016 study based in Washington, DC. Participants were 891 Black men, 18 to 44 years of age, who completed computer surveys. We used moderated mediation to test the study’s conceptual model.

Results. The results showed significant indirect effects of incarceration history on depressive symptoms via negative police encounters and police avoidance. Unemployment moderated the indirect effect via police avoidance. Participants with a history of incarceration who were unemployed reported significantly higher police avoidance and, in turn, higher depressive symptoms. Moderation of unemployment on the indirect effect via negative police encounters was not significant.

Conclusions. There is a critical need to broaden research on the health impact of mass incarceration to include other aspects of criminal justice involvement (e.g., negative police encounters and police avoidance) that negatively affect Black men’s mental health.

Mass incarceration is a potent reminder that the historical legacies of slavery, the Black Codes, and Jim Crow endure for US Black communities.1 In a 2018 report to the United Nations, the Sentencing Project detailed the magnitude of racial inequities in mass incarceration: “African Americans are more likely than White Americans to be arrested; once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to experience lengthy prison sentences.”2

A vast theoretical3 and empirical literature documents the deleterious impact of mass incarceration on the health not just of those incarcerated1,3,4 but also their families5 and, in the case of neighborhoods characterized by high rates of incarceration, entire communities.6 Yet, critical empirical gaps exist about the influence of “the full spectrum of mass incarceration”4(p46)—stop and frisk, hyperpolicing and aggressive policing, arrest, cash bail, sentencing, incarceration, parole, and reincarceration, for example—on health in Black communities. Our aims in this study were to examine negative police encounters and police avoidance as mediators of incarceration histories and depressive symptoms among US Black men and to assess the role of unemployment as a moderator.

Police encounters in Black communities are a critical antecedent to mass incarceration but are an understudied link in the health inequities pathway. Black and White communities have starkly and distinctly different experiences with police. Relative to White people, police speak more disrespectfully to Black people,7 are approximately 5 times more likely to shoot Black people,8 and typically use more excessive nonlethal and lethal force with Black suspects.9 “The Talk”—a routine conversation in which Black parents educate their children, typically sons, about how to minimize the chance of injury and death if stopped by police—accentuates the ubiquity of Black people’s negative interactions with police.

Black communities also bear the disproportionate brunt of hyperpolicing, an aggressive form of policing characterized by intensive and extensive police surveillance, the “noticing” of crime in racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods, and the designation of entire neighborhoods and residents as potential or actual criminals.4 Hyperpolicing highlights “both the breadth and depth of the criminal justice system’s reach [with respect to] health and well-being.”4(p46) Hyperpolicing also transcends racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods. In recent years, a slew of cell phone videos have captured the alarming frequency with which White people perturbed by Black people’s most mundane acts (e.g., 2 Black men awaiting a colleague in a Starbucks, a Black male realtor monitoring properties, Black people barbequing in a park) have summoned police to serve as what Phillip Atiba Goff, president of the Center for Policing Equity, has termed “personal racism concierges.”10

Black men are the focus of the current research. Black boys and men have been subjected to aggressive policing at every stage in the criminal justice system,11 but so too have Black girls, women, and transgender people. As such, it is important to note that our study’s specific focus on Black men is not meant to connote that negative police encounters and mass incarceration are the sole purview of Black men.

Nonetheless, the impact of mass incarceration on Black men is staggering. Black males represent just 6% of the US population but in 2017 were sentenced to prison at a rate almost 6 times greater than that of their White counterparts.12 The disparity is particularly stark for younger Black males; those 18 and 19 years old are approximately 12 times more likely to be imprisoned than their White counterparts. And although the latest federal prison statistics document that the imprisonment rate among Black males dropped by one third in 2017—reaching the lowest rate in almost 28 years—this promising news is outweighed by the reality that Black men continue to bear the disproportionate brunt of the full spectrum of mass incarceration.11

NEGATIVE POLICE ENCOUNTERS AND POLICE AVOIDANCE

Police encounters in Black communities include a broad continuum of interactions that range in severity and lethality, such as racial profiling, stop and frisk, police harassment, arrests, hyperpolicing, aggressive policing, police brutality (e.g., chokeholds13), and nonlethal and lethal police shootings. Although a description of each police encounter type is beyond the scope of this article, 2 types are disturbingly commonplace for Black men: stop and frisk and fatal police shootings. These negative encounters often lead Black men to actively avoid the police.

Stop-and-frisk policies allow police to detain and question pedestrians for whom there is a “reasonable suspicion” that they have committed, are committing, or are about to commit a crime and pat them down in search of a weapon. Relative to White men, Black men are disproportionately more likely to be victims of stop-and-frisk searches even though White men, when stopped, are more likely to be found with weapons.14 In Washington, DC, the site of our study, Black residents account for 83% of stop-and-frisk searches despite representing just 47% of the population.15

As with stop and frisk, Black men are also the group most likely to be shot and killed by police.1,11,13 Underscoring the link between structural racism and fatal police shootings of Black people is empirical evidence that a state’s racism index is a significant predictor of Black–White disparities in police shootings of victims not known to be armed.16 This harsh reality is well documented in mass and social media coverage of cell phone and surveillance camera encounters in which police officers have fatally shot Black boys and men, most of whom were unarmed.

Fear and mistrust of and animus for police are recurrent themes in qualitative research with Black men17 and scholarship focused specifically on the policing of Black men.11,13 We conceptualize Black men’s behaviors to avoid police as a specific type of system avoidance, the practice by which people with prior criminal justice system experience—“those who have been stopped, arrested, convicted or incarcerated”18(p19)—avoid contact with and surveillance by medical, financial, employment, and educational institutions that maintain formal records.18

DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS

Despite mounting advocacy to conceptualize excessive police violence and aggressive policing as public health concerns,19–21 research on negative police encounters as social-structural drivers of health inequities in Black communities is rare. Among the small group of studies documenting the harmful impact of aggressive policing on health are those that show that living in neighborhoods where police use more aggressive pedestrian stop and frisks is significantly associated with negative health outcomes for Black and Latino residents22; that Black and Latino men who report more frequent police encounters, particularly those perceived as more intrusive and unfair, report higher rates of trauma and anxiety23; and that frequent reports of discriminatory police and law enforcement encounters are associated with higher depressive symptom scores among Black men.24

Ecosocial25 and biopsychosocial26 theoretical frameworks posit that repeated exposures to social-structural stressors such as racism and, in the case of our study, negative police encounters and police avoidance trigger severe psychological and physiological stress responses that result in negative health outcomes. Because Black people on parole and probation are disproportionately more likely than their White counterparts to be monitored aggressively and reincarcerated for minor or technical violations,27 Black men with incarceration histories may have more negative police encounters and motivations to avoid police. As such, negative police encounters and police avoidance are potential mechanisms in the link between incarceration histories and depressive symptoms. In light of empirical evidence that a history of incarceration28 is associated with depression, especially among young Black men,29 we examined depressive symptoms as our main outcome.

Incarceration, unemployment, and depressive symptoms are inextricably linked among Black men. Because multiple social-structural stressors (e.g., having a criminal record and being unemployed) are deleterious to mental health,25,26 we assessed whether unemployment moderates the indirect link between incarceration history and depressive symptoms via negative police encounters and police avoidance.

In our study, we addressed substantial gaps in public health research about the effects of criminal justice exposure on Black men’s health. Informed by ecosocial and biopsychosocial theoretical frameworks, we tested a conceptual model of negative police encounters and police avoidance as mediators of the relationship between incarceration history and depressive symptoms among a sample of Black men in Washington, DC. We also assessed whether current unemployment moderated these mediated effects (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual Model of Indirect Effects of Incarceration History on Depressive Symptoms via Negative Police Encounters and Police Avoidance, Moderated by Unemployment Among Black Men

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001

METHODS

We collected data between 2015 and 2016 as part of Menhood, a mixed-methods study focusing on the effects of individual and neighborhood-level social-structural stressors (e.g., racial discrimination, incarceration, unemployment) and resilience on the sexual HIV risk and protective behaviors of Black men in Washington, DC. Eligible participants self-identified as non-Latino Black/African American cisgender men and were between 18 and 50 years of age (qualitative phase participants) and 18 and 44 years of age (quantitative phase participants; reflecting the highest HIV prevalence age range). Participants screened for eligibility for the quantitative phase of the study had to live in the neighborhood in which they were screened and had to report having had sex within the preceding 6 months. All participants received a $50 cash incentive.

Qualitative Phase

Focus group participants were from 9 socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods in Washington, DC. In 2013 and 2014, recruiters approached and screened potential participants in public settings (e.g., streets, corner stores, barbershops). Focus groups ranged from 5 to 11 participants, lasted 90 to 120 minutes, were conducted by a trained Black male facilitator, were digitally audio-recorded and professionally transcribed, and were analyzed via thematic analysis (focus group demographics are highlighted in Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Focus group narratives informed this study’s quantitative measures of negative police encounters and police avoidance. In response to questions about what one might see during a visit to participants’ neighborhoods, respondents—65% of whom reported a history of incarceration—frequently recounted negative encounters with police, most typically hyperpolicing, stop and frisk, harassment, and violence. Focus group narratives also detailed a variety of strategies that respondents reported using to avoid interactions with police such as planning their walking or driving routes and limiting the number of Black men with whom they walked or drove.

Quantitative Phase

We used a sampling frame of census block groups with at least 40% Black households for the quantitative phase. This yielded 256 census block groups (from a total of 450) from which we randomly selected addresses using the US Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File. We sent letters about the study to prospective households before the interview team’s arrival. Teams of 2 Black interviewers then visited identified households to screen for eligibility, obtain written informed consent, and collect the data. Participants completed an interviewer-administered computer-assisted personal interviewing survey with an audio-computer-assisted self-interview section including questions about sexual behavior (these data were not included in our analyses). The response rate was 80%.

Measures

Incarceration history.

Participants’ incarceration history was assessed with a single yes or no question: “Have you ever been incarcerated (i.e., confined in jail or prison while waiting for a trial or after being convicted of a crime) since turning 18 years old?”

Police encounters.

Participants responded to 12 questions about the frequency of their encounters with police over the preceding 12 months (e.g., “How often have the police asked you for your photo ID?” and “How often have the police stopped and questioned you?”) developed from focus group findings. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 5 (more than 10 times). We used the mean of the 12 items as an indicator for this variable. The Cronbach α value for this measure was 0.94.

Police avoidance.

Participants responded to 6 questions about strategies used to avoid police (e.g., “How often do you watch how you dress to avoid getting harassed by the police?” and “How often do you drive in a way to make sure that you do not attract attention from the police?”) developed from focus group findings. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). We used the mean of the 6 items as an indicator of police avoidance. The Cronbach α value was 0.88.

Depressive symptoms.

Participants responded to the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale30 to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms in the preceding 2 weeks (e.g., “You felt lonely” and “Your sleep was restless”). Two positively worded items were reversed so that higher mean scores reflected higher levels of depressive symptoms. Response options ranged from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all of the time). We used the sum of the 10 items as an indicator of depression. The Cronbach α value was 0.72.

Covariates.

Sociodemographic characteristics included as covariates were

1. age;

2. education, ranging from 1 (some high school) to 5 (graduate degree);

3. current unemployment (0 = employed, 1 = unemployed); and

4. relationship status, ranging from 0 (single [single, widowed, or divorced]) to 1 (committed [married or cohabitating partnership]).

Statistical Analysis

Moderated mediation occurs when the strength of an indirect effect is contingent on the level of a moderator variable. On the basis of our conceptual model (Figure 1), we hypothesized that the link between incarceration history and depressive symptoms would be mediated by negative police encounters and police avoidance and that these indirect effects would be stronger for unemployed participants. To test this hypothesis, we employed a first-stage moderation model (model 8) from PROCESS macro version 3.4,31 with 10 000 bootstrapping resamples used to produce 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects. To assess the significance of the moderated pathways, we used the index of moderated mediation.31 Statistical significance was set at P < .05. We used SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) in conducting all of our analyses. Because we excluded 43 cases owing to missing data for one or more of the included variables, our analytical sample size for the moderated mediation analysis was 848.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sample’s demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics for negative encounters with police, police avoidance, and depressive symptoms, for the entire sample and separately by incarceration history.

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics, Negative Police Encounters, Police Avoidance, and Depressive Symptoms Among a Weighted Sample of Black Men, Overall and by History of Incarceration: Washington, DC, 2015–2016

| History of Incarceration |

|||

| Overall,a No. (%) or Mean ± SD | No,b No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Yes,b No. (%) or Mean ±SD | |

| Sample size | 891 (100) | 629 (70.6) | 251 (28.2) |

| Educationc | |||

| Some high school | 91 (10.2) | 56 (8.9) | 35 (13.9) |

| High school or equivalent | 333 (37.4) | 204 (32.4) | 129 (51.4) |

| Some college | 264 (29.6) | 196 (31.2) | 68 (27.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 129 (14.5) | 115 (18.3) | 14 (5.6) |

| Graduate degree | 60 (6.7) | 56 (8.9) | 4 (1.6) |

| Currently unemployedc | 323 (36.2) | 200 (31.8) | 123 (49.0) |

| Married or cohabitating | 328 (36.8) | 222 (35.3 | 106 (42.2) |

| Aged | 30.25 ±7.80 | 29.36 ±7.92 | 32.46 ±7.04 |

| Negative police encountersd | 1.22 ±1.11 | 1.00 ±1.01 | 1.76 ±1.16 |

| Police avoidanced | 1.13 ±0.90 | 0.98 ±0.85 | 1.50 ±0.90 |

| Depressive symptomse | 7.82 ±5.45 | 7.57 ±5.41 | 8.47 ±5.53 |

Note. The sample size was n = 891.

Percentages are for the full sample.

Percentages are specific to the stratified sample.

Significant group difference (χ2; P < .001).

Significant group difference (t test; P < .001).

Significant group difference (t test; P < .05).

Results from the moderated mediation analysis (Table 2) indicate that the direct effect of incarceration history on depressive symptoms was not significant regardless of unemployment status. The indirect effect of incarceration history on depressive symptoms mediated by negative police encounters was significant regardless of unemployment status (employed: effect = 0.049; 95% CI = 0.018, 0.086; unemployed: effect = 0.058; 95% CI = 0.021, 0.103). The moderated mediation index for negative police encounters was not significant (index = 0.009; 95% CI = −0.014, 0.037), indicating no significant differences by unemployment status for the indirect effect via negative police encounters.

TABLE 2—

Regression Coefficients From a First-Stage Moderated Mediation Model of Depressive Symptoms on Incarceration History via Negative Police Encounters and Police Avoidance, Conditioned on Unemployment Among Black Men: Washington, DC, 2015–2016

| Coefficienta (SE or Bootstrap SE; 95% CI) | t | |

| Outcome variable: depressive symptoms (R2 = 0.062; P < .001) | ||

| Incarceration history | −0.079 (0.058; −0.193, 0.034) | −1.376 |

| Negative police encountersb | 0.070 (0.020; 0.031, 0.109) | 3.526 |

| Police avoidanceb | 0.070 (0.024; 0.024, 0.117) | 2.976 |

| Unemployment | −0.111 (0.050; −0.109, 0.087) | −0.223 |

| Incarceration history × unemployment | 0.108 (0.082; −0.052, 0.268) | 1.323 |

| Age | 0.001 (0.003; −0.005, 0.006) | 0.234 |

| Marital status | −0.048 (0.040; −0.126, 0.031) | −1.189 |

| Education | −0.033 (0.021; −0.074, 0.007) | −1.607 |

| Conditional indirect effects via negative police encounters by unemploymentc | ||

| Employedb | 0.049 (0.017; 0.018, 0.086) | . . . |

| Unemployedb | 0.058 (0.021; 0.021, 0.103) | . . . |

| Conditional indirect effects via police avoidance by unemploymentd | ||

| Employedb | 0.023 (0.011; 0.005, 0.046) | . . . |

| Unemployedb | 0.047 (0.019; 0.013, 0.085) | . . . |

Note. CI = confidence interval. The sample size was n = 843.

Ordinary least squares regression coefficient.

Statistically significant.

Index of moderated mediation = 0.009 (SE = 0.013; 95% CI = −0.014, 0.037).

Index of moderated mediation = 0.024 (SE = 0.014; 95% CI = 0.003, 0.055).

The indirect effect of incarceration history on depressive symptoms mediated by police avoidance was significant for both employed (effect = 0.023; 95% CI = 0.005, 0.046) and unemployed (effect = 0.047; 95% CI = 0.013, 0.085) men. The moderated mediation index in this case, however, was significant (index = 0.024; 95% CI = −0.003, 0.055), indicating that the indirect effect of incarceration history on depressive symptoms via police avoidance was significantly higher for unemployed men.

DISCUSSION

Policing is a critical step in the mass incarceration pipeline for Black boys and men. Policing has historically been the purview of disciplines such as criminology and law, not public health. Consequently, there is a considerable void of research on police encounters as a social-structural driver of mass incarceration and health inequities. Notably, our study is one of the first to demonstrate that negative police encounters and police avoidance are empirically documented pathways in the incarceration history and depression link for Black men.

Our study’s results echo burgeoning advocacy to consider police violence a critical public health issue20,21,24 with at least 3 noteworthy empirical contributions. First, our results showed that, for Black men with incarceration histories, police interactions need not rise to the level of the excessive violence that characterizes most mass and social media accounts to have an impact on depressive symptoms. For example, most of the items on the negative police encounter measure assessed police interactions that were nonviolent (e.g., being approached for just standing on the street) or deemed harassing (being harassed while outside of one’s home or in a public place). Just 2 questions assessed violent (e.g., being pushed or hit by a police officer) and threatening (e.g., having police point a gun at you) actions.

This finding has important implications for future research and interventions involving police violence. Namely, it suggests that future research on Black men’s police encounters should assess a broader continuum of police interactions, ranging, for example, from racial profiling to excessive violence. And because racial profiling presages “almost every stop, frisk, search, assault, or killing of Black boys and men,”11(pxix) our research also bolsters the need for implicit racial bias training to address all aspects of police interactions with Black people, not just aggressive encounters or shootings.2

A second contribution highlights one of our most interesting findings, namely that police avoidance mediates the incarceration history and depressive symptoms pathway. Ecosocial and biopsychosocial theoretical frameworks help explain how avoidance behaviors may get embodied.25 Whereas police avoidance may be a coping mechanism for Black men without an incarceration history, for those who have been incarcerated, the cumulative stress and hypervigilance needed to avoid police may become maladaptive if the stress of engaging in these strategies depletes the very psychological resources needed to protect against depressive symptoms. As for the mediating effects of negative police encounters, as previous studies have shown, these encounters may be directly or vicariously traumatic and stressful22; psychological responses may be exacerbated for men who fear reincarceration. Negative encounters with police may also be associated with trauma experienced firsthand, incarceration, or vicarious trauma from having observed police violence.17

Finally, given the relative dearth of research on the mechanisms that link incarceration and Black men’s depressive symptoms,28 our study highlights a need for additional research to better understand the pathways by which police avoidance affects depressive symptoms. We found that the individual effects of negative police encounters and police avoidance were significant for men with incarceration histories regardless of unemployment status. The effects of police avoidance were especially strong among participants who both had incarceration histories and were unemployed. A possible explanation for this result is that these participants may be more likely to stay at home, which is a successful strategy for avoiding police but not for reducing depressive symptoms (e.g., by visiting friends and family for social support or spending time outdoors).

Limitations

Our study should be considered within the context of 5 limitations. First, the study’s cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about relationships between variables. Second, the incarceration measure assessed lifetime incarceration only. There is a need for future research to assess the impact of both current and previous incarceration on depressive symptoms to account for divergences in short-term and long-term effects.28 For example, depressive symptoms may worsen after incarceration as returning citizens face a proliferation of stress (e.g., finding a job, financial or material hardships, and returning to children, romantic partners, and families) related to their community reintegration.28 The absence of information about the timing of incarceration (e.g., time since last release) also limited our ability to assess how or whether negative police encounters reported in the preceding 12 months might have led to incarceration. Similarly, we lacked information about the timing of police avoidance behaviors.

Third, to limit the exorbitant recruitment costs associated with recruiting Black men between 18 and 44 years of age, we restricted the sampling frame to those who lived in census block groups that were at least 40% Black. Consequently, our sample does not reflect the experiences of Black men who live in more socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse Washington, DC, neighborhoods.

Fourth, although the measure that we used to assess depressive symptoms has been validated with Black men, there are legitimate concerns that the criteria informing the instrument neglect how depressive symptoms manifest in Black men by emphasizing more emotion-focused symptoms (e.g., crying) and obscuring the more culturally and masculinity-specific depressive symptoms that many Black men express (e.g., restricted emotionality, anger, aggression, sleep disturbances).29,32 Finally, although our results may be generalizable to other predominantly low- and middle-income Black men who live in urban settings, the extent to which the results are generalizable to upper-middle-class men and those who live in rural areas is unknown.

Conclusions

Our research lays the groundwork for future studies of how negative police encounters and police avoidance may mediate the relationship between mass incarceration and health in other Black populations such as girls, women, and transgender people. One theoretical implication of our work is that, pursuant to research on the collateral damage of mass incarceration,6,22 future research in this area should conceptualize Black men’s incarceration histories and experiences with police not simply as individual-level demographic or risk factors but rather as larger social-structural contextual determinants of health inequity.6

Our study has obvious and important implications for policy, including those addressed in the 2018 American Public Health Association policy statement Addressing Law Enforcement Violence as a Public Health Issue.21 In addition, our study highlights a critical need for implicit racial bias training for police to reduce negative police encounters, hyperpolicing, aggressive policing, and fatal police shootings of Black men. There is also a need to repeal stop-and-frisk laws in light of their racially disparate impact on Black men, most of whom are found innocent,14 and empirical evidence indicating that stop and frisks are associated with negative health outcomes (e.g., greater odds of an asthma episode22) as well as trauma and anxiety.23

Our research also underscores a dire need for structural interventions to reduce personal racism concierge10 calls. Recent initiatives in which city (e.g., Grand Rapids, MI) and state (e.g., New York, Michigan) lawmakers have introduced legislation to criminalize calls to police involving racially biased complaints against people of color offer a potential, albeit difficult to enforce, remedy.10

It is noteworthy that Black men’s qualitative focus group narratives, as opposed to the existing theoretical and empirical literature, shaped our examination of negative police encounters and police avoidance. This affirms 2 key principles of critical health equity research. First, because many qualitative methods align epistemologically with critical approaches that emphasize the dismantling of oppressive structures, they are invaluable for research on social-structural drivers of health inequities.33 Second, these methods bolster core tenets of critical theoretical frameworks (e.g., intersectionality and critical race theory34) regarding the necessity and utility of centering the experiences of marginalized groups such as Black men to better ground research and inform multilevel interventions aimed at reducing health inequities and improving health and well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant awarded to L. Bowleg from the National Institute of Mental Health (7 R01 MH100022-02).

The Temple University Institute for Survey Research (Philadelphia, PA) conducted all sampling and recruitment for the study. We are especially grateful to the men who participated in all phases of the study. Their participation is invaluable to this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional review board at George Washington University approved all of the study procedures. All study participants provided informed consent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sentencing Project. Report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the US criminal justice system. Available at: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 3.Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–1474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankenship KM, del Rio Gonzalez AM, Keene DE, Groves AK, Rosenberg AP. Mass incarceration, race inequality, and health: expanding concepts and assessing impacts on well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2018;215:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Wildeman C, Wang EA, Matusko N, Jackson JS. A heavy burden: the cardiovascular health consequences of having a family member incarcerated. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):421–427. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Hamilton A, Uddin M, Galea S. The collateral damage of mass incarceration: risk of psychiatric morbidity among nonincarcerated residents of high-incarceration neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):138–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voigt R, Camp NP, Prabhakaran V et al. Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(25):6521–6526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702413114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Justice. Policing and Homicide, 1976–98: Justifiable Homicide by Police, Police Officers Murdered by Felons. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith BW. Structural and organizational predictors of homicide by police. Policing. 2004;27(4):539–557. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thebault R, Brice-Saddler M. This city wants to make it illegal to call 911 on people of color who are just living their lives. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/04/25/last-year-livingwhileblack-went-viral-now-city-wants-make-biased-calls-illegal. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 11.Davis AJ, editor. Policing the Black Man. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bronson J, Carson EA. Prisoners in 2017. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p17.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 13.Butler P. Chokehold: Policing Black Men. New York, NY: New Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York Civil Liberties Union. Stop-and-frisk in the de Blasio era. Available at: https://www.nyclu.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/20190314_nyclu_stopfrisk_singles.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 15.American Civil Liberties Union. Racial disparities in DC policing: descriptive evidence from 2013–2017. Available at: https://www.acludc.org/en/racial-disparities-dc-policing-descriptive-evidence-2013-2017. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 16.Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A et al. The relationship between structural racism and Black-White disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(2):106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich JA, Grey CM. Pathways to recurrent trauma among young Black men: traumatic stress, substance use, and the “Code of the Street. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):816–824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brayne S. Surveillance and system avoidance: criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. Am Sociol Rev. 2014;79(3):367–391. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. Characterizing perceived police violence: implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1109–1118. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and Black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Public Health Association. Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue. Available at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence. Accessed December 15, 2019.

- 22.Sewell AA, Jefferson KA. Collateral damage: the health effects of invasive police encounters in New York City. J Urban Health. 2016;93(suppl 1):42–67. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-0016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English D, Bowleg L, del Río-González AM, Tschann JM, Agans RP, Malebranche DJ. Measuring Black men’s police-based discrimination experiences: development and validation of the Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) Scale. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2017;23(2):185–199. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–944. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Columbia University Justice Lab. Too big to succeed: the impact of the growth of community corrections and what should be done about it. Available at: https://justicelab.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/Too_Big_to_Succeed_Report_FINAL.pdf.

- 28.Turney K, Wildeman C, Schnittker J. As fathers and felons: explaining the effects of current and recent incarceration on major depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(4):465–481. doi: 10.1177/0022146512462400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perkins DEK, Kelly P, Lasiter S. “Our depression is different”: experiences and perceptions of depression in young Black men with a history of incarceration. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28(3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendrick L, Anderson NLR, Moore B. Perceptions of depression among young African American men. Fam Community Health. 2007;30(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowleg L. Towards a critical health equity research stance: why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(5):677–684. doi: 10.1177/1090198117728760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase “women and minorities”: intersectionality, an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]