Abstract

Background:

Surgical training has long been to “never let the sun set on a bowel obstruction” without an operation to rule out and/or treat compromised bowel. However, advances in diagnostics have called into question the appropriate timing of non-emergent operations and expectant management is increasingly used. We performed a systematic review to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of expectant management for adhesive small bowel obstruction (aSBO) compared to early, non-emergent operation.

Materials & Methods:

We queried PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases for studies (1990–present) comparing early, nonemergent operations and expectant management for aSBO (PROSPERO #CRD42017057676).

Results:

Of 4873 studies, 29 cohort studies were included for full-text review. Four studies directly compared early surgery with expectant management, but none excluded patients who underwent emergent operations from those having early non-emergent surgery, precluding a direct comparison of the two treatment types of interest. When aggregated, the rate of bowel resection was 29% in patients undergoing early operation vs. 10% in those undergoing expectant management. The rate of successful, nonoperative management in the expectant group was 58%. There was a 1.3-day difference in LOS favoring expectant management (LOS 9.7 vs. 8.4 days), and the rate of death was 2% in both groups.

Conclusion:

Despite the shift towards expectant management of aSBO, no published studies have yet compared early, nonemergent operation and expectant management. A major limitation in evaluating the outcomes of these approaches using existing studies is confounding by indication related to including patients with emergent indications for surgery on admission in the early operative group. A future study, randomizing patients to early non-emergent surgery or expectant management, should inform the comparative safety and value of these approaches.

Keywords: Small bowel obstruction, Non-operative management, Systematic review, Adhesive small bowel obstruction

Introduction

Despite advances in technique and minimally invasive approaches, small bowel obstruction (SBO) remains a common surgical problem in the United States accounting for approximately 350,000 hospital stays averaging 8 days in length, and costing up to $2.3 billion, annually.1, 2 The historical paradigm for surgical training around the management of SBO has been to “never let the sun rise and set” without an operation to rule out compromised bowel.3 In the era prior to ubiquitous CT scanning, early surgical exploration of patients was needed to rule out ischemia, closed-loop obstruction, or SBO due to tumor, hernia, or other causes. However modern cross-sectional imaging combined with lab tests allow surgeons to readily distinguish most patients that have indications for and emergency operation on presentation from those with benign non-ischemic adhesive SBO (aSBO).4

In the setting of a complete aSBO without indications for emergency surgery on presentation, the contemporary surgeon and patient now have a choice of early operation or expectant management, allowing the chance to resolve the aSBO without an operation. Many surgeons no longer strictly follow the historical paradigm of routine, early operative intervention and instead practice expectant management (gastric decompression and serial examination); however, this practice has not clearly been supported by evidence. Current guidelines from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) recommend 3–5 days of non-operative management for patients with SBO based upon limited evidence.5 In prior work, our research group hypothesized that there was significant practice variation in the timing of surgery for aSBO. In a quantitative analysis, Washington State surgeons who were interviewed about their management of SBO reported a tolerance for watchful waiting ranging from 12 h to greater than 7 days. A third of surgeons interviewed wait 3 days or longer prior to operating.6 Given the apparent frequency of expectant management and variation in the timing of non-emergent surgery, we aimed to evaluate the evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of expectant management compared with usual care (early non-emergent surgery) for patients with aSBO.

Methods

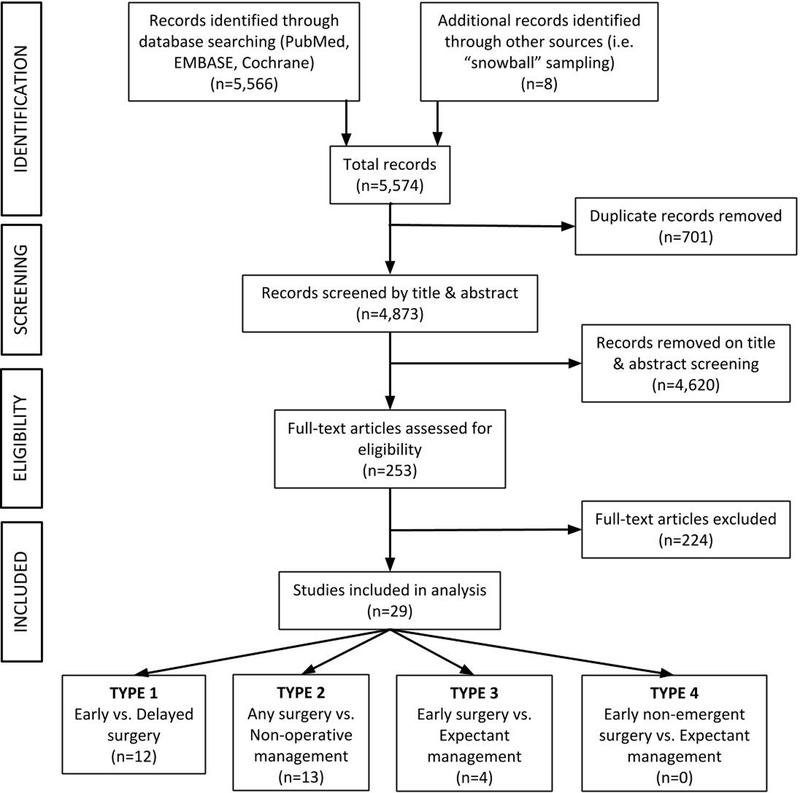

We performed a comprehensive and systematic review of the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases to identify all studies pertaining to the safety or effectiveness of expectant management for adhesive small bowel obstruction (aSBO). Search terms were developed in order to identify two general types of studies: (1) those comparing early and delayed surgery for aSBO and (2) those reporting nonoperative management for aSBO. Search terms are summarized in Table 1. Searches were limited to full-text articles in the English language involving human subjects published between January 1, 1990 and August 31, 2016. This study was designed and performed according to PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) standards (see Supplement A for the completed PRISMA checklist) (Fig. 1).7 The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews, registration #: CRD42017057676).8

Table 1:

Search strategies applied in systematic review of the literature regarding

| Studies on the timing SBO management | Studies comparing surgery and non-operative management | |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“surgical management”[Title/Abstract] OR “operative management”[Title/Abstract] OR surgical[Title/Abstract] OR surgery[tiab] OR adhesiolysis[Title/Abstract] OR laparoscopy[Title/Abstract] OR laparotomy[Title/Abstract] OR celiotomy[Title/Abstract] OR laparoscopic[Title/Abstract] OR operation[tiab]) AND ((“Intestinal Obstruction”[Mesh] AND “Intestine, Small”[Mesh])OR (obstruction[Title/Abstract] AND (“Intestine, Small”[Mesh] OR small bowel[Title/Abstract] OR small intestine[Title/Abstract] OR adhesive[Title/Abstract] OR adhesion[Title/Abstract] OR mechanical[Title/Abstract]))) AND (timing[Title/Abstract] OR time[Title/Abstract] OR delay[Title/Abstract] OR early[Title/Abstract] OR late[Title/Abstract] OR hours[Title/Abstract] OR days[Title/Abstract] OR length[Title/Abstract]) NOT (Crohn’s[tiab] OR “Inflammatory Bowel Disease”[tiab]) AND ((“1990/01/01”[PDAT] : “3000/12/31”[PDAT]) AND English[lang]) Records: 2650 |

((non-operative[Title/Abstract] OR conservative[Title/Abstract] OR expectant[Title/Abstract] OR nonoperative[Title/Abstract] OR non operative[Title/Abstract]) AND (treatment[Title/Abstract] OR management[Title/Abstract])) AND ((“Intestinal Obstruction”[Mesh] AND “Intestine, Small”[Mesh])OR(obstruction[Title/Abstract] AND (“Intestine, Small”[Mesh] OR small bowel[Title/Abstract] OR small intestine[Title/Abstract] OR adhesive[Title/Abstract] OR adhesion[Title/Abstract] OR mechanical[Title/Abstract]))) NOT (Crohn’s[tiab] OR “Inflammatory Bowel Disease”[tiab]) AND ((“1990/01/01”[PDAT] : “3000/12/31”[PDAT]) AND English[lang]) Records: 444 |

| EMBASE | (‘surgical management’:ab,ti OR ‘operative management’:ab,ti OR surgical:ab,ti OR surgery:ab,ti OR adhesiolysis:ab,ti OR laparoscopy:ab,ti OR laparotomy:ab,ti OR celiotomy:ab,ti OR laparoscopic:ab,ti OR operation:ab,ti) AND ‘small intestine obstruction’/exp AND(timing:ab,ti OR time:ab,ti OR delay:ab,ti OR early:ab,ti OR late:ab,ti OR hours:ab,ti OR days:ab,ti OR length:ab,ti) NOT(crohn*:ab,ti OR ‘inflammatory bowel disease’:ab,ti) AND [english]/lim AND [1990–2016]/py Records: 2079 |

((non-operative:ab,ti OR conservative:ab,ti OR expectant:ab,ti OR nonoperative:ab,ti OR non operative:ab,ti) AND (treatment:ab,ti OR management:ab,ti)) AND ‘small intestine obstruction’/exp NOT (crohn*:ab,ti OR ‘inflammatory bowel disease’:ab,ti) AND [english]/lim AND [1990–2016]/py Records: 161 |

| Cochrane | obstruction or adhes* in Title, Abstract, Keywords AND intestin* in Title, Abstract, Keywords AND tim* or early or late or non-operat* or nonoper* in Title, Abstract, Keywords NOT postoperative in Title, Abstract, Keywords NOT malignant in Title, Abstract, Keywords Publication Year from 1990, IN Cochrane Reviews (Reviews and Protocols), Other Reviews, Trials, Methods Studies, Technology Assessments, Economic Evaluations and Cochrane Groups (Word variations have been searched) Records: 232 |

|

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for identification, screening, full-text review, and inclusion of studies of small bowel obstruction

Title and Abstract Screening

Database searches yielded 5566 records. After duplicates were removed (n = 701), a total of 4873 unique records were screened by title and abstract for inclusion in the study. On screening, records were included for full-text review if they met the following three criteria:

the study included patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction or with bowel obstruction not otherwise specified (e.g., all types of bowel obstruction)

for studies reporting expectant management of aSBO, the study reported the rate of failure of expectant management (i.e., number ultimately requiring surgery)

for studies reporting only surgical management, patients were grouped by time until surgery (e.g., early surgery group vs. delayed surgery group);

Studies were excluded for any of the following five conditions:

the study did not report any short term clinical outcomes (e.g., wound infection, length of stay, death)

the study specifically analyzed patients with obstruction due to hernia, mass, volvulus, or inflammatory bowel disease;

the study specifically included patients with early postoperative SBO (i.e., obstruction occurring within 30 days of a primary abdominal operation);

the study was of pediatric patients

the study was a research letter, review article, case report, case series of ten or fewer patients, or was published in abstract form only (i.e., studies were only included if a full-text manuscript was published).

Each record was reviewed by at least two members of the research team. Knowing that usual scientific abstracts may not provide sufficient detail, we took a conservative approach and included for full-text review those studies that either satisfied all or may on full-text review satisfy all screening criteria. Some studies reported a greater number of patients than those described in this review but if results were not reportable by the groups defined in this review those subjects were excluded. Any disagreement between screeners was resolved through a consensus process by the entire research group. Title and abstract screening was facilitated by standardized online systematic review software (Covidence).9

Full-Text Review

After title and abstract screening, 253 studies were selected for full-text review. On full-text review, studies were examined for eligibility to ensure they met all screening criteria. Common reasons for exclusion included studies not reporting clinical outcomes after intervention, studies not grouping surgical patients by time until surgery, and studies of SBO specifically due to causes other than adhesion (i.e., inflammatory bowel disease or cancer). Figure 2 demonstrates the PRISMA flow diagram for identification, screening, full-text review, and inclusion of studies of small bowel obstruction. After full-text review, 28 studies were selected for inclusion in the study. We performed “snowball” sampling of the references in all included studies, yielding eight additional studies of interest, of which only one met criteria for inclusion. For each of the 29 studies ultimately selected for inclusion, researchers recorded the following: study design, data source, dates of data collection, type of SBO studied, methods for patient selection, exclusion criteria applied in cohort selection, use of CT scan for diagnosis of SBO, and details of any adjusted analyses performed. We recorded the following outcomes: bowel resection, surgical site infection (SSI), mortality, length of hospital say (LOS), as well as healthcare costs. Some studies simply reported the rate of “complications” among treatment groups but this type of composite outcome varied significantly from study to study and therefore it was not documented for this review. Lastly, we documented the time threshold defining early versus delayed surgery and the rate of failure of non-operative management, as applicable. Study features and unadjusted outcomes from included studies are summarized in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Data collection was performed using an online survey platform (REDCap v.7.2.2).21

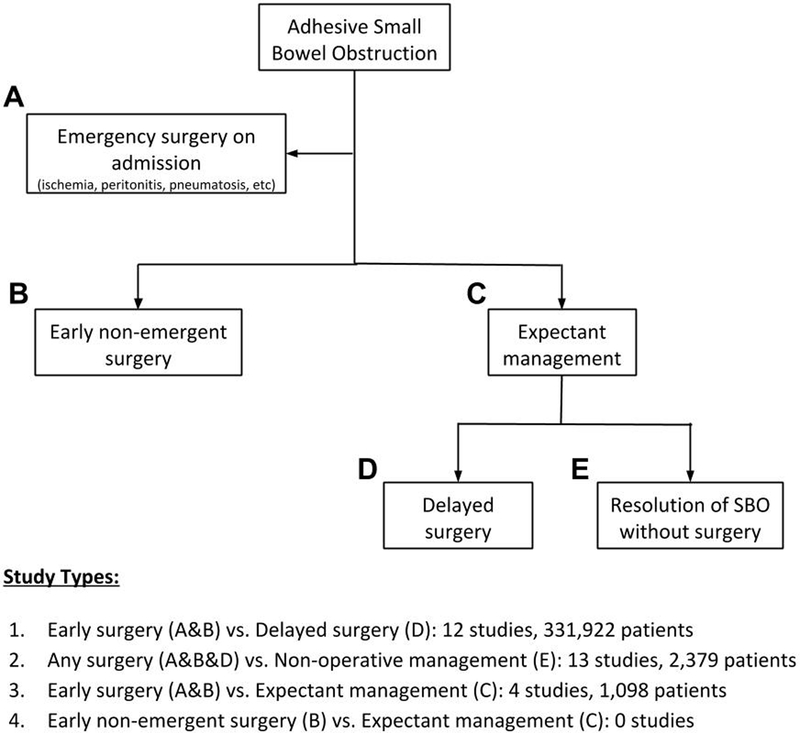

Figure 2.

Concept chart demonstrating possible treatment groups for management of small bowel obstruction and corresponding study types.

Table 2:

Details of studies on the management of small bowel obstruction

| Study Design | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Year | Journal | Country | Data Collection |

Data Source | Retrospective Cohort | Prospective Cohort | Randomized Trial |

| 2a: TYPE 1 - Studies comparing early surgery versus delayed surgery | ||||||||

| Cox et al.25 | 1993 | Aus NZ J Surg | Australia | 1982–1990 | Single institution | X | ||

| Seror et al.26 | 1993 | Am J Surg | Israel | 1976–1990 | Single institution | X | ||

| Fevang et al.12 | 2000 | Ann Surg | Norway | 1961–1995 | Single institution | X | ||

| Fevang et al.27 | 2003 | Scand J Surg | Norway | 1961–1995 | Single institution | X | ||

| Leung et al.20 | 2012 | Am Surg | USA | 2003–2007 | Single institution | X | ||

| Joseph et al.28 | 2013 | Am Surg | USA | 2001–2006 | Single institution | X | ||

| Schraufnagel et al.3 | 2013 | JTACS | USA | 2009 | National claims database | X | ||

| Chu et al.11 | 2013 | J GI Surg | USA | 2007 | National claims database | X | ||

| Teixeira et al.29 | 2013 | Ann Surg | USA | 2005–2010 | National clinical database | X | ||

| Keenan et al. 14 | 2014 | JTACS | USA | 2005–2010 | National clinical database | X | ||

| Jafari et al.15 | 2015 | Am Surg | USA | 2001–2011 | National claims database | X | ||

| Karamanos et al.30 | 2016 | World J Surg | USA | 2004–2010 | National clinical database | X | ||

| 2b: TYPE 2 - Studies comparing any surgery versus non-operative management | ||||||||

| Matter et al.31 | 1997 | Eur J Surg | Israel | 1980–1994 | Single institution | X | ||

| Menzies et al. 16 | 2001 | Ann R Col Surg Eng | UK | - | Multi institution | X | ||

| Kössi et al.32 | 2004 | Scand J Surg | Finland | 1999 | Multi institution | X | ||

| Ryan et al. 33 | 2004 | ANZ J Surg | Australia | 1999–2002 | Single institution | X | ||

| Jones et al.34 | 2007 | Am J Surg | USA | 2004–2005 | Single institution | X | ||

| Chen et al.35 | 2008 | J Chin Int Med | China | 1995–2002 | Single institution | X | ||

| Rocha et al.18 | 2009 | Arch Surg | USA | 2000–2005 | Single institution | X | ||

| Isaksson et al.36 | 2011 | Eur J Tr Emerg Surg | Sweden | 2005–2006 | Single institution | X | ||

| Springer et al.37 | 2014 | Can J Surg | Canada | 2011–2012 | Single institution | X | ||

| Meier et al.38 | 2014 | Colon Dis | Switzerland | 2004–2007 | Single institution | X | ||

| Kulvatunyou et al.39 | 2015 | JTACS | USA | 2011–2013 | Multi institution | X | ||

| Akrami et al. 40 | 2015 | Bull Emerg Trauma | Iran | 2006–2012 | Single institution | X | ||

| Bueno-Lledo et al. 41 | 2016 | Dig Surg | Spain | 2008–2013 | Single institution | X | ||

| 2c: TYPE 3 - Studies comparing early surgery versus expectant management | ||||||||

| Sosa et al.42 | 1993 | Am Surg | USA | 1980–1985 | Single institution | X | ||

| Fevang et al.43 | 2002 | Eur J Surg | Norway | 1994–1995 | Single institution | X | ||

| Nauta44 | 2005 | JACS | USA | 1991–2004 | Single institution | X | ||

| Bauer et al.45 | 2015 | Am Surg | USA | 2001–2011 | Single institution | X | ||

Table 3:

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies on the management of small bowel obstruction

| Inclusions | Exclusions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBO type | Pts admitted w/SBO | Pts operated w/SBO | Emergency surgery | Tumors | Hernia | IBD | Early post-op SBO | Reports preop CT? | Definition of early surgery (days) | |

| 3a: TYPE 1 - Studies comparing early surgery versus delayed surgery | ||||||||||

| Cox et al.25 | Adhesive | X | X | X | X | ≤2 | ||||

| Seror et al.26 | Not specified | X | X | ≤5 | ||||||

| Fevang et al.12 | Not specified | X | X | ≤1 | ||||||

| Fevang et al.27 | Not specified | X | X | ≤1 | ||||||

| Leung et al.20 | Not specified | X | X | ≤1 | ||||||

| Joseph et al.28 | Adhesive | X | X | ≤2 | ||||||

| Schraufnagel et al.3 | Not specified | X | <4 | |||||||

| Chu et al.11 | Not specified | X | ≤2 | |||||||

| Teixeira et al.29 | Adhesive | X | ≤1 | |||||||

| Keenan et al. 14 | Not specified | X | X | X | ≤1 | |||||

| Jafari et al.15 | Adhesive | X | X | X | <7 | |||||

| Karamanos et al.30 | Adhesive | X | <1 | |||||||

| 3b: TYPE 2 - Studies comparing any surgery versus non-operative management | ||||||||||

| Matter et al.31 | Adhesive | - | - | X | - | |||||

| Menzies et al. 16 | Adhesive | - | - | X | X | - | ||||

| Kössi et al.32 | Not specified | - | - | X | - | |||||

| Ryan et al. 33 | Adhesive | - | - | - | ||||||

| Jones et al.34 | Not specified | - | - | X | X | - | ||||

| Chen et al.35 | Not specified | - | - | - | ||||||

| Rocha et al.18 | Not specified | - | - | X | - | |||||

| Isaksson et al.36 | Not specified | - | - | X | - | |||||

| Springer et al.37 | Not specified | - | - | X | X | - | ||||

| Meier et al.38 | Adhesive | - | - | X | - | |||||

| Kulvatunyou et al.39 | Adhesive | - | - | X | X | X | X | X | X | - |

| Akrami et al. 40 | Not specified | - | - | - | ||||||

| Bueno-Lledo et al. 41 | Adhesive | - | - | X | X | X | X | X | X | - |

| 3c: TYPE 3 - Studies comparing early surgery versus expectant management | ||||||||||

| Sosa et al.42 | Not specified | - | - | X | X | X | X | - | ||

| Fevang et al.43 | Adhesive | - | - | X | X | - | ||||

| Nauta44 | Not specified | - | - | X | X | - | ||||

| Bauer et al.45 | Not specified | - | - | X | X | X | X | - | ||

Table 4:

Selected results from studies on the management of small bowel obstruction.

| Cohort Size | Bowel Resection | SSI | Mortality | LOS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a: TYPE 1 - Studies comparing early surgery versus delayed surgery | |||||||||||

| Early surgery, n |

Delayed surgery, n |

Early surgery, n (%) |

Delayed surgery, n (%) |

Early surgery, n (%) |

Delayed surgery, n (%) |

Early surgery, n (%) |

Delayed surgery, n (%) |

Early surgery, days |

Delayed surgery, days |

||

| Cox et al.25 | 15 | 26 | - | - | 3 (20) | 6 (23) | - | - | - | - | |

| Seror et al.26 | 61 | 19 | - | - | - | - | 2 (3) | 1 (5) | - | - | |

| Fevang et al.12 | 334 | 489 | - | - | - | - | 6 (2) | 32 (7) | - | - | |

| Fevang et al.27 | 142 | 329 | 21 (15) | 20 (28) | - | - | - | - | 7.0 | 7.4 | |

| Leung et al.20 | 325 | 80 | 39 (12) | 23 (29) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Joseph et al.28 | 30 | 34 | - | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 7.6 | 12.3 | |

| Schraufnagel et al.3 | 3854 | 972 | 934 (24) | 274 (28) | - | - | 88 (2) | 50 (5) | - | - | |

| Chu et al.11 | 2897 | 2546 | - | - | - | - | 60 (2) | 78 (3) | 7.3 | 8.8 | |

| Teixeira et al.29 | 1641 | 2522 | 399 (24) | 671 (27) | 164 (10) | 325 (13) | 50 (3) | 163 (7) | - | - | |

| Keenan et al. 14 | 3153 | 1830 | - | - | 391 (12) | 227 (12) | 99 (3) | 73 (4) | 8.0 | 9.0 | |

| Jafari et al.15 | 294,461 | 14,554 | 1635 (1) | 204 (1) | - | - | 204 (1) | 597 (4) | - | - | |

| Karamanos et al.30 | 554 | 1054 | 148 (27) | 304 (29) | 62 (11) | 154 (15) | 22 (4) | 101 (10) | - | - | |

| Totals | 307,467 | 24,455 | 3176 (1) | 1,496 (8) | 620 (12) | 712 (13) | 531 (<1) | 1096 (5) | 7.5 | 9.4 | |

| 4b: TYPE 2 - Studies comparing any surgery versus non-operative management | |||||||||||

| Non-op mgmt, n |

Surgery, n |

Non-op mgmt, n (%) |

Surgery, n (%) |

Non-op mgmt, n (%) |

Surgery, n (%) |

Non-op mgmt, n (%) |

Surgery, n (%) |

Non-op mgmt, days |

Surgery, days |

||

| Matter et al.31 | 178 | 68 | - | 24 (35) | - | - | 2 (1) | 2 (3) | - | - | |

| Menzies et al. 16 | 69 | 41 | - | - | - | - | 5 (7) | 4 (10) | 7 | 16.6 | |

| Kössi et al.32 | 84 | 39 | - | 15 (39) | - | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | |

| Ryan et al. 33 | 17 | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.1 | 21.6 | |

| Jones et al.34 | 43 | 53 | - | 27 (51) | - | 7 (13) | 4 (9) | 2 (4) | - | - | |

| Chen et al.35 | 250 | 101 | - | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - | |

| Rocha et al.18 | 66 | 79 | - | 35 (44) | - | - | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 4.7 | 10.8 | |

| Isaksson et al.36 | 65 | 44 | - | 10 (23) | - | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 | 13 | |

| Springer et al.37 | 51 | 53 | - | 18 (34) | - | - | 2 (4) | 8 (15) | 3 | 10 | |

| Meier et al.38 | 85 | 136 | - | 44 (32) | - | - | 0 (0) | 9 (7) | 6.6 | 12 | |

| Kulvatunyou et al.39 | 148 | 52 | - | 20 (39) | - | - | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 3 | 10 | |

| Akrami et al. 40 | 302 | 109 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.6 | 8.1 | |

| Bueno-Lledo et al. 41 | 198 | 37 | - | 7 (19) | - | - | - | - | 4.9 | 7.4 | |

| Totals | 1556 | 823 | - | 200 (36) | - | 7 (13) | 15 (2) | 28 (4) | 4.4 | 12.0 | |

| Table 4c: TYPE 3 - Studies comparing early surgery versus expectant management | |||||||||||

| Early surgery, n |

Expectant mgmt, n |

Operations after expectant mgmt, n (%) |

Early Surgery, n (%) |

Expectant mgmt, n (%) |

Early surgery, n (%) |

Expectant mgmt, n (%) |

Early surgery, n (%) |

Expectant mgmt, n (%) |

Early surgery days |

Expectant mgmt (days) |

|

| Sosa et al.42 | 21 | 95 | 33 (35) | 4 (19) | 9 (9) | 1 (5) | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 12.3 | 13.7 |

| Fevang et al.43 | 14 | 95 | 34 (36) | 5 (36) | 4 (4) | - | - | 1 (7) | 2 (2) | 7 | 3 |

| Nauta44 | 72 | 341 | 47 (14) | 22 (31) | 0 (0) | - | - | 2 (3) | 5 (1) | - | - |

| Bauer et al.45 | 106 | 354 | 254 (72) | 31 (29) | 71 (20) | 9 (8) | 21 (6) | 1 (1) | 10 (4) | - | - |

| 213 | 885 | 368 (42) | 62 (29) | 84 (10) | 10 (8) | 27 (6) | 4 (2) | 19 (2) | 9.7 | 8.4 | |

Analysis

Based upon a concept map of possible treatment groups for aSBO (Fig. 2), we assigned studies into one of four study types. Type 1 studies compared early surgery for aSBO (including either emergency surgery for ischemia, peritonitis, etc. or early non-emergent surgery) versus delayed surgery occurring after some period of watchful waiting. All patients in Type 1 studies underwent surgical intervention for their obstruction. Type 2 studies compared patients undergoing any surgery for aSBO (early or delayed) versus patients who were successfully managed non-operatively. Type 3 studies compared patients undergoing early surgery (early emergent or non-emergent) versus expectant management (including those who required delayed surgery and those who resolved without surgery). Finally, Type 4 studies compared early non-emergent surgery (excluding patients who required emergency surgery on presentation) versus expectant management. In any study arm that included expectant management, surgical outcomes were reported among those who ultimately required an operation. Evidence from all included studies was graded using a modified Downs & Black grading scheme to estimate the associated risk of bias.16 The Downs and Black checklist was designed to assess both randomized and nonrandomized studies and provides four sub-scales of quality assessment including reporting, external quality, bias, and confounding. A rating for power is also provided in the checklist, but was excluded in this study due to inadequate information in most studies to allow for a power calculation. Because of significant heterogeneity in study design and a considerable risk of bias and residual confounding across selected studies, we did not perform a meta-analysis of primary data.

Results

From a total of 4873 unique records, 29 studies reporting outcomes of 335,399 patients with SBO were identified for inclusion.

Type 1 Studies—Early Vs. Delayed Surgery for aSBO

We identified 12 retrospective cohort studies (331,922 patients) comparing outcomes between groups of patients with aSBO undergoing either early or delayed surgery from single institutions, and national clinical or claims databases (Tables 2, 3, and 4). Six studies studied specifically patients with aSBO while the remainder did not specify the type of obstruction and only two studies report the use of CT scans for diagnosis of SBO. The median time cutoff for defining early surgery was 1.5 days (range 1–7 days). Rates of bowel resection were lower in early surgery groups (mean 1%, range 1– 27%) than delayed surgery groups (mean 8%, range 1–29%) in all six studies reporting this outcome. Four studies reported rates of SSI which were similar between early (mean 12%, range 10–20%) and delayed (mean 13%, range 12–23%) surgery groups. Rates of mortality were lower in the early surgery group (mean < 1%, range 0–4%) compared with the delayed surgery group (mean 5%, range 3–10%) in all nine studies reporting deaths. Average hospital LOS was 7.5 days (range 7–8) after early surgery and 9.4 days (range 7.4–12.3) in four reporting studies. Only one study reported costs, finding that costs of hospitalization were lower among patients undergoing early surgery ($45,233) compared with delayed surgery ($71,892).12 Adjusted analysis of the risk of mortality was reported in six studies using either multivariable adjustment or propensity score matching controlling for either patient factors or both patient and operative factors.3, 12, 17–19, 22 Four of six adjusted analyses identified a significant association of delayed surgery with significantly greater odds of mortality while two analyses did not find any significant difference between groups.

Type 2 Studies—Any Surgery Vs. Non-operative Management

An additional ten retrospective cohort and three prospective cohort studies were identified (2379 patients) comparing any surgical intervention (regardless of timing) against nonoperative management for SBO. Three of these studies were multi-institution while the remainder were from single institutions. Only two studies applied strict criteria to exclude patients requiring emergency surgery, early post-operative SBO, and those with obstructions due to tumors, hernia, or IBD. Six of 13 studies used CT scan diagnosis to confirm the diagnosis of obstruction. Bowel resection occurred in 36% of patients undergoing surgery (range 19–51%) in the nine studies reporting this outcome. Mortality was 4% after surgery (range 0–15%) and 2% after non-operative management (range 0– 9%) in nine studies. Average LOS was considerably shorter after non-operative management (4.4 days, range 2 –7) than after surgical management (12 days, range 7.4 –21.6). Cost of non-operative management was also lower ($2329) than surgery ($6782) as reported by a single study.23 No studies reported adjusted outcomes between operative and nonoperative groups.

Type 3 Studies —Early Surgery Vs. Expectant Management

We identified four studies (one prospective and three retrospective cohorts, 1098 patients, all from single institutions) comparing early surgery (either emergency surgery on presentation or early, non-emergent surgery) against expectant management. Two of these studies applied exclusions to early post-operative bowel obstruction and patients with obstruction due to tumor, hernia, and IBD. Of 885 patients who underwent expectant management, 42% ultimately required surgery (range 14 –72%). Rates of bowel resection were lower among patients managed expectantly (average 10%, range 0 –20%) compared with those treated by early surgery (average 29%, range 19 –36%). SSI was documented in two studies and rates were 8% after early surgery (range 5–8%) and 6% after expectant management (range 6 –6%). Mortality was similar among both groups (2% (range 0–7%) after early surgery and 2% (range 1–4%) after expectant management). Average LOS was 9.7 days after early surgery and 8.4 days after expectant management in two studies. No cost data or adjusted analyses were reported.

Type 4 Studies —Early Non-emergent Surgery Vs. Expectant Management

We did not identify any studies that compared early nonemergent surgery (i.e., excluding patients with emergent indication for surgery on presentation) against expectant management. However, in snowball sampling of references, we identified an abstract reporting a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 127 patients randomized by a single surgeon to early non-emergent surgery or expectant management.20 Because it was not published as a full-text, this study was not formally included in the systematic review. In this study, rates of death were 6% vs 3%, and rates of bowel resection 22% vs 17% for early surgery and expectant management, respectively (all p > 0.05). In total, 65% of those treated with expectant management went did not require an operation.

Grading Quality of Observational Studies

Upon grading, major limitations of studies included in Table 4 this review included failure to report a distribution of confounders between comparison groups (24 of 29 studies), failure to provide estimates of random variability for outcomes (23 of 29 studies), a lack of reporting characteristics of subjects that were lost to follow-up (19 of 29 studies), absence of randomized assignment to treatment groups (29 of 29 studies), and inadequate adjustment for confounding (21 of 29 studies). A table detailing the grading of evidence from studies included in this review can be referenced in Supplement B.

Discussion

After systematic review of the literature, we identified 29 studies that might inform the safety and effectiveness of expectant management compared with usual care (early nonemergent surgery) for aSBO. All studies were observational and none captured patient-reported outcomes. These studies were classified into four groups by type of treatment or management reported. Most studies either compared early versus delayed surgery or any surgery versus non-operative management. While four studies reported outcomes from patients managed by early surgery compared with expectant management, we did not identify any full-text studies reporting outcomes of early non-emergent surgery versus expectant management. An RCT, published as an abstract only, did not identify significant differences between patients randomized to early surgery or expectant management. Because of methodological flaws present in all included studies, there remains an important evidence gap for surgeons considering watchful waiting for patients with aSBO.

Unadjusted outcomes from studies comparing early and delayed surgery appear to favor early operative intervention in rates of bowel resection and mortality, hospital LOS, and even cost. In addition, among those studies reporting adjusted outcomes, two-thirds demonstrated lower odds of mortality associated with early surgery while the other third did not observe a significant difference. Because they present an incomplete picture of patients who present with bowel obstruction however, these data should be interpreted with caution. Studies that analyze data exclusively from patients who underwent surgery for SBO fail to capture the experience of patients who resolved their obstruction without surgery. The study design comparing early versus delayed surgery introduces bias into the delayed surgery group because these patients represent only those who either developed an indication for surgical exploration or those who failed to progress after a period of observation. A more appropriate study design is one which analyzes all patients who are observed clinically over some period of time, whether they ultimately require surgery or not (i.e., expectant management).

Among studies comparing any surgery versus nonoperative management, none applied adjusted analysis but unadjusted outcomes appear to favor non-operative management in rates of mortality, LOS, and cost. However, these studies all contain a serious design flaw due to confoundingby-indication, meaning the groups studied likely varied in disease severity based upon which treatment they received. Patients who required surgery for their obstruction may have had emergency indications for surgery (i.e., peritonitis, closed-loop obstruction) or failed to progress after observation, both of which portend worse outcomes, while those managed successfully without surgery likely represent either the healthiest patients or those with the mildest forms of obstruction. Despite the large number of studies of this type, these data do not provide meaningful insight into the safety of expectant management of patients with SBO.

The findings from four studies of early surgery versus expectant management were mixed. Rates of bowel resection were somewhat lower after expectant management; however SSI, mortality, and LOS appear similar whether patients underwent either treatment modality. Examining these studies in detail revealed another methodological flaw, specifically that none excluded patients who required emergency surgery on admission from the early surgery group. This means that early surgery in these studies included both patients who were operated upon prophylactically early in their hospital course as well as those who required urgent or emergent exploration. For surgeons choosing whether to proceed with an early operation or undertake watchful waiting for patients with SBO, these studies provide incomplete data regarding this choice. Among the studies included in this review, we did not identify any that compared early non-emergent surgery (i.e., surgery performed early in the hospital course absent emergent indications) with expectant management. The RCT identified on snowball reference review (published as an abstract only) did not reveal any significant differences in rates of bowel resection, death, or LOS between patients randomized to early surgery or expectant management for aSBO. The authors conclude that expectant management is safe given that 65% of patients in this group resolved without an operation.20 Since this study was not published in full-text form, our ability to evaluate these findings is limited. We were unable to assess adjustment for confounders, patient characteristics, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and whether blinding may have been present.

There are important limitations to this review. First, we searched for studies that grouped patients by the timing of their surgery or whether the patients underwent expectant or non-operative management. Other studies have approached this question by examining time from presentation to surgery as a continuous variable;24 however, generating meaningful conclusions presents methodological challenges. Still other studies have applied prediction modeling to determine which patient features indicate the need for an early exploratory surgery for SBO.14, 25, 26 There remains uncertainty about the comparative effectiveness between the historic standard early surgery for all SBOs and the apparently common yet varied practice of expectant management and predictive modeling studies have not resolved this gap in evidence. Second, we have excluded data from studies published prior to 1990. While this approach may have overlooked relevant studies for review, it is unlikely that any data on outcomes of SBOs prior to the era of ubiquitous CT scanners would be applicable to today’s practice. Third, when deciding on whether or not to consider expectant management for obstructed patients, there is an important influence of other diagnostic and prognostic procedures. Strong evidence has emerged to suggest that enteral contrast studies, such as Gastrografin®, can help in determining those patients who are highly likely to resolve without surgery (those who have partial aSBO demonstrated by contrast moving to colon).10, 27, 28 While not the subject of this review, this diagnostic modality should be used in future studies to identify which patients qualify for a trial of expectant management.

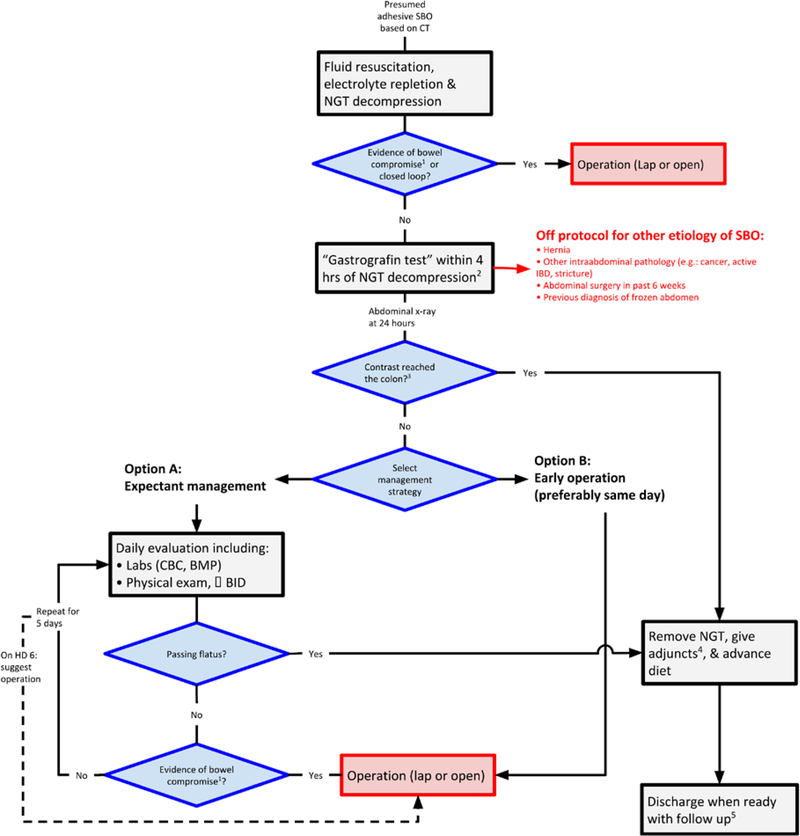

The surgical community has general agreement on indications for emergent surgery in the setting of an aSBO. However, for those patients that do not meet criteria to go to emergently to the operating room, previously identified surgeon practice variability in the timing and indications for operative interventions motivated a search for evidence to support the safety of this practice.6 After a systematic review of the literature, we conclude that there are significant evidence gaps to support the safety and effectiveness of expectant management compared to early non-emergent surgery for aSBO. Washington State surgeons participating in the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) network are now collecting data on expectant versus early operative management for SBO. At the University of Washington, a protocol for the management of suspected complete SBO due to adhesions has been developed to support standardization of care and allow for future studies on optimal treatment pathways (Fig. 3). Importantly, the protocol is meant to apply only to patients who do not require an emergency surgery and also fail to pass contrast to the colon within 24 h of administration (e.g., fail a water soluble oral contrast test). Such standardization is the first step preparing for research to address these evidence gaps.

Figure 3.

Clinical care protocol for the management of adhesive bowel obstruction, developed at the University of Washington Medical Center

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anjali Truitt, PhD MPH and Erika Wolff, PhD from the Surgical Outcomes Research Center as well as Ann W. Gleason from the University of Washington Health Sciences Library for technical assistance in completing this project.

Funding Information

Drs. Thornblade, Verdial, and Bartek are supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32DK070555.

Abbreviations

- aSBO

Adhesive small bowel obstruction

- CT

Computed tomography

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- LOS

Length of stay

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- SBO

Small bowel obstruction

- SSI

Surgical site infection

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sikirica V, Bapat B, Candrilli SD, Davis KL, Wilson M, Johns A. The inpatient burden of abdominal and gynecological adhesiolysis in the US. BMC Surg. 2011;11(1):13 10.1186/1471-2482-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray NF, Denton WG, Thamer M, Scott C, Henderson C, Perry S. Abdominal adhesiolysis: Inpatient care and expenditures in the United States in 1994. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(1):1–9. 10.1016/S1072-7515(97)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schraufnagel D, Rajaee S, Millham FH. How many sunsets? Timing of surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction: a study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(1):181–189. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827891a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallo RD, Salem L, Lalani T, Flum DR. Computed tomography diagnosis of ischemia and complete obstruction in small bowel obstruction: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 9(5):690–694. 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maung AA, Johnson DC, Piper GL, et al. Evaluation and management of small-bowel obstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5):S362–S369. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827019de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornblade LW, Truitt AR, Davidson GH, Flum DR, Lavallee DC. Surgeon attitudes and practice patterns in managing small bowel obstruction: a qualitative analysis. J Surg Res. 2017;219:347–353. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):873–880. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews.

- 9.Covidence. https://www.covidence.org/. Accessed April 21, 2017.

- 10.Galardi N, Collins J, Friend K. Use of early gastrografin small bowel follow-through in small bowel obstruction management. Am Surg. 2013;79(8):794–796. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23896246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Galati M, et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2013 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):42 10.1186/1749-7922-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu DI, Gainsbury ML, Howard LA, Stucchi AF, Becker JM. Early versus late adhesiolysis for adhesive-related intestinal obstruction: a nationwide analysis of inpatient outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(2):288–297. 10.1007/s11605-012-1953-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbas S, Bissett IP, Parry BR. Oral water soluble contrast for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;284(3):478–482. 10.1002/14651858.CD004651.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aldemir M, Yagnur Y, Taçyildir I. The Predictive Factors for the Necessity of Operative Treatment in Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction Cases. 2017;5458(January). 10.1080/00015458.2003.11681150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S-C. Nonsurgical management of partial adhesive smallbowel obstruction with oral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(10):1165–1169. 10.1503/cmaj.1041315. J Gastrointest Surg (2019) 23:846–859 857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teixeira PG, Karamanos E, Talving P, Inaba K, Lam L, Demetriades D. Early operation is associated with a survival benefit for patients with adhesive bowel obstruction. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):459–465. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a1b100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenan JE, Turley RS, McCoy CC, Migaly J, Shapiro ML, Scarborough JE. Trials of nonoperative management exceeding 3 days are associated with increased morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for uncomplicated adhesive small bowel obstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(6):1367–1372. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jafari MD, Jafari F, Foe-Paker JE, et al. Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction in the United States: Has Laparoscopy Made an Impact? Am Surg. 2015;81(10):1028–1033. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26463302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosley Shoaib. Operative versus conservative management of adhesional intestinal obstruction. Br J Surg. 2000;87(3):362–373. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01383-17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.RedCap. https://redcap.iths.org/. Accessed April 21, 2017.

- 22.Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L, Søreide O. Complications and Death After Surgical Treatment of Small Bowel Obstruction. Ann Surg. 2000;231(4):529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menzies D, Parker M, Hoare R, Knight A. Small bowel obstruction due to postoperative adhesions: treatment patterns and associated costs in 110 hospital admissions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(1): 40–46. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2503561&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha FG, Theman TA, Matros E, Ledbetter SM, Zinner MJ, Ferzoco SJ. Nonoperative management of patients with a diagnosis of high-grade small bowel obstruction by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2009;144(11):1000–1004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=19917935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung AM, Vu H. Factors predicting need for and delay in surgery in small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 2012;78(4):403–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary EA, Desale SY, Yi WS, et al. Letting the sun set on small bowel obstruction: Can a simple risk score tell us when nonoperative care is inappropriate? Am Surg. 2014;80(6):572–579. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khasawneh MA, Ugarte ML, Srvantstian B, Dozois EJ, Bannon MP, Zielinski MD. Role of gastrografin challenge in early postoperative small bowel obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(2): 363–368. 10.1007/s11605-013-2347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roadley G, Cranshaw I, Young M, Hill AG. Role of gastrografin in assigning patients to a non-operative course in adhesive small bowel obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(10):830–832. 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox MR, Gunn IF, Eastman MC, Hunt RF, Heinz AW, Serials HS. The safety and duration of non-operative treatment for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63(5):367–371. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8481137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seror D, Feigin E, Szold A, et al. How conservatively can postoperative small bowel obstruction be treated? Am J Surg. 1993;165(1):121–5–6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8418687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fevang BT, Fevang JM, Svanes K, Viste A. Delay in operative treatment among patients with small bowel obstruction Background and Aims: Delay in operative treatment for small bowel obstruction ( SBO ) has been shown to affect outcome adversely . The objective of this study was to detect time tre. Scand J Surg. 2003:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fevang BT, Jensen D, Svanes K, Viste A, (2002) Early Operation or Conservative Management of Patients with Small Bowel Obstruction?. The European Journal of Surgery 168(8): 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joseph SP, Simonson M, Edwards C. “Let”s just wait one more day’: impact of timing on surgical outcome in the treatment of adhesion-related small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 2013;79(2):175–179. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23336657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karamanos Efstathios, Dulchavsky Scott, Beale Elizabeth, Inaba Kenji, Demetriades Demetrios, (2016) Diabetes Mellitus in Patients Presenting with Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: Delaying Surgical Intervention Results in Worse Outcomes. World Journal of Surgery 40(4):863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matter I, Khalemsky L, Abrahamson J, Nash E, Sabo E, Eldar S. Does the index operation influence the course and outcome of adhesive intestinal obstruction? Eur J Surg. 1997;163(10):767–772. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9373228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kössi J, Salminen P, Laato M. The epidemiology and treatment patterns of postoperative adhesion induced intestinal obstruction in varsinais-suomi hospital district Background and Aims: The epidemiology and treatment patterns of postoperative adhesion induced intestinal obstruction. Scand J Surg. 2004:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan Matthew D., Wattchow David, Walker Margaret, Hakendorf Paul, (2004) Adhesional small bowel obstruction after colorectal surgery. ANZ Journal of Surgery 74(11):1010–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones K, Mangram AJ, Lebron RA, Nadalo L, Dunn E. Can a computed tomography scoring system predict the need for surgery in small-bowel obstruction? Am J Surg. 2007;194(6 PG-780–784): 780–784. http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L350086556NS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen XZ, (2008) Etiological factors and mortality of acute intestinal obstruction:a review of 705 cases. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine 6(10):1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isaksson K, Weber E, Andersson R, Tingstedt B, (2011) Small bowel obstruction: early parameters predicting the need for surgical intervention. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 37(2):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springer Jeremy, Bailey Jonathan, Davis Philip, Johnson Paul, (2014) Management and outcomes of small bowel obstruction in older adult patients: a prospective cohort study. Canadian Journal of Surgery 57(6):379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier Raphael P. H., Saussure Wassila Oulhaci de, Orci Lorenzo A., Gutzwiller Eveline M., Morel Philippe, Ris Frédéric, Schwenter Frank, (2014) Clinical Outcome in Acute Small Bowel Obstruction after Surgical or Conservative Management. World Journal of Surgery 38(12):3082–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulvatunyou N, Pandit V, Moutamn S, et al. A multi-institution prospective observational study of small bowel obstruction: Clinical and computerized tomography predictors of which patients may require early surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):393–398. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A M, H AG, B M, Z V Clinical characteristics of bowel obstruction in Southern Iran; results of a single center experience. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2015;3(1):22–26. 10.7508/beat.2015.01.004.Introduction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jose Bueno-Lledó, Sebastian Barber, Javier Vaqué, Mateo Frasson, Eduardo Garcia-Granero, Manuel Juan-Burgueño, (2016) Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: Predictive Factors of Lack of Response 858 J Gastrointest Surg (2019) 23:846–859 in Conservative Management with Gastrografin. Digestive Surgery 33(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sosa J, Gardner B. Management of patients diagnosed as acute intestinal obstruction secondary to adhesions. Am Surg. 1993;59(2):125–128. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8476142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nauta RJ. Advanced abdominal imaging is not required to exclude strangulation if complete small bowel obstructions undergo prompt laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(6 PG-904–911):904–911. http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L40744799NS-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauer J, Keeley B, Krieger B, et al. Adhesive Small Bowel [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.