Abstract

Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4), an intracellular lipid chaperone and adipokine, is expressed by lung macrophages, but the function of macrophage–FABP4 remains elusive. We investigated the role of FABP4 in host defense in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Compared with wild-type (WT) mice, FABP4-deficient (FABP4−/−) mice exhibited decreased bacterial clearance and increased mortality when challenged intranasally with P. aeruginosa. These findings in FABP4−/− mice were associated with a delayed neutrophil recruitment into the lungs and were followed by greater acute lung injury and inflammation. Among leukocytes, only macrophages expressed FABP4 in WT mice with P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Chimeric FABP4−/− mice with WT bone marrow were protected from increased mortality seen in chimeric WT mice with FABP4−/− bone marrow during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, thus confirming the role of macrophages as the main source of protective FABP4 against that infection. There was less production of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) in FABP4−/− alveolar macrophages and lower airway CXCL1 levels in FABP4−/− mice. Delivering recombinant CXCL1 to the airways protected FABP4−/− mice from increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Thus, macrophage-FABP4 has a novel role in pulmonary host defense against P. aeruginosa infection by facilitating crosstalk between macrophages and neutrophils via regulation of macrophage CXCL1 production.—Liang, X., Gupta, K., Rojas Quintero, J., Cernadas, M., Kobzik, L., Christou, H., Pier, G. B., Owen, C. A., Çataltepe, S. Macrophage FABP4 is required for neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia.

Keywords: CXCL1, host defense, innate immunity

Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) is a member of the FABP family of small-MW (∼15 kDa) intracellular lipid chaperones (1). FABP4 is most abundantly expressed in adipocytes but has also been detected in macrophages and a subset of endothelial cells (2–4). FABP4 exhibits a range of functions in each of these cell types, including regulation of glucose, lipid metabolism, and inflammation; cell survival; and cell proliferation (2, 5–9). The underlying mechanisms of the intracellular biologic activities of FABP4 remain poorly understood but are generally thought to be related to its lipid binding activity. FABP4 is also secreted from the adipocytes through a nonclassic pathway and functions as an adipokine, regulating hepatic glucose production (10). Serum FABP4 levels are significantly increased in obese mice, and genetic deficiency and antibody neutralization of FABP4 improves systemic glucose homeostasis and inflammation (11, 12). Serum FABP4 levels are also increased in patients with metabolic syndrome (13–15), and individuals with a low-expression variant of the FABP4 allele are protected against diabetes and cardiovascular disease (16, 17). Based on these preclinical and clinical observations, there is growing interest in targeting FABP4 as a potential treatment for diseases characterized by meta-inflammation.

In macrophages, FABP4 expression is induced by several agents, including PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ) agonists, oxidized LDL, TNF-α, and LPS, and is down-regulated by unsaturated fatty acids (18–20). Genetic deficiency or chemical inhibition of FABP4 in macrophage cell lines markedly diminishes the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), IL-1β, and IL-6 (7, 21). Furthermore, the proinflammatory activity of macrophage-FABP4 has a key role in promoting atherosclerosis in murine models (6, 22). We and others (4, 20) have shown that macrophages are the main source of FABP4 in the lung. Pulmonary macrophages are a crucial component of defense against infectious agents because of their ability to phagocytose and process pathogens and to produce inflammatory and chemotactic mediators (23, 24). Although the proinflammatory activities of macrophage-FABP4 suggest that it may have a role in pulmonary host defense, to our knowledge, the role of FABP4 in the context of an infection has not yet been studied.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative pathogen that causes severe respiratory tract infections leading to acute lung injury (ALI) and to its more severe from—acute respiratory distress syndrome—especially in immunocompromised, hospitalized, or ventilated patients (25, 26). P. aeruginosa is also the most common cause of chronic airway infection and deterioration of pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis and advanced, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27, 28). Many P. aeruginosa isolates are multiantibiotic resistant and are associated with high morbidity, mortality, and health care burden (29, 30). Macrophages have a direct role in the initial recruitment of neutrophils into P. aeruginosa–infected murine lungs (31, 32). Depletion of alveolar macrophages results in prolonged inflammation, worse lung injury, and decreased survival in mice with P. aeruginosa pneumonia (33). We postulated that deficiency of macrophage-FABP4 would increase the morbidity and mortality associated with P. aeruginosa pneumonia and investigated that hypothesis in a murine model of P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Age- and sex-matched FABP4−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background (34) and C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used in all studies. Mice were 8–10 wk old for all studies, except for mice infected after bone marrow (BM) transplantation around 16 wk of age. All procedures performed on mice were approved by the Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use committees.

Mouse model of P. aeruginosa pneumonia

Pneumonia was induced by intranasal (i.n.) instillation of 50 µl of a bacterial suspension containing 2 × 109 or 2 × 108 colony-forming units (CFUs) of P. aeruginosa S470 strain (a clinical isolate obtained from the late Dr. Jo Rae Wright, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA) under isoflurane anesthesia. In pilot experiments in which we tested a range of P. aeruginosa inocula, we found 2 × 108 and 2 × 109 CFUs to be the 20 and 80% lethal doses, respectively, at 24 h after infection in FABP4−/− mice, whereas 2 × 109 CFU was the 20% lethal dose, and 2 × 108 did not induce mortality in WT mice. Therefore, we employed 2 × 109 CFUs for the survival experiments and 2 × 108 CFUs for all other experiments. Control mice were given 50 µl of LPS-free PBS i.n. In cohorts of mice treated with 2 × 109 CFUs P. aeruginosa, survival of the animals was recorded at 24 h. In cohorts of mice treated with 2 × 108 CFUs P. aeruginosa, euthanasia was performed by CO2 exposure at 6 or 24 h after infection. The right lung was either lavaged or inflated with paraformaldehyde, whereas the left lung was used for assessment of wet-to-dry lung-weight ratios, bacterial burdens, or preparations of lung homogenates as described in detail below.

Determination of bacterial load in tissues

Left lung and spleen were homogenized in PBS. Bacterial load was determined by plating serial, 10-fold dilutions of the homogenates onto Luria-Bertani agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h before the colonies were counted.

Histology and lung injury scoring

Mice were euthanized and lungs inflated to 20 cmH2O with 4% paraformaldehyde. Lungs were washed with PBS and dehydrated in 70% ethanol. The right lung was sectioned, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Features of bacterial pneumonia (inflammatory cells, edema, cell fragmentation, hemorrhage, and interstitial expansion) were evaluated semiquantitatively by a lung pathologist (L.K.) blinded to the genotypes based on an index generated by multiplying a severity score (0–3) by the extent of the involvement in the section (0–3 score) (35).

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Left main-stem bronchus was ligated, and right lung was lavaged twice with 0.5 ml ice-cold PBS. The lavages were combined and centrifuged at 400 g for 3 min. The supernatant was stored at −80°C for cytokine, chemokine, and albumin measurements. The bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were resuspended in PBS and enumerated with a hemocytometer. Differential cell counts were performed on cytocentrifuge preparations stained with modified Wright’s stain.

Wet-to-dry lung-weight ratios

Left lungs were weighed immediately after removal (wet weight) and again after incubation at 65°C for 48 h (dry weight). Wet-to-dry lung weight ratios were calculated.

BAL fluid albumin levels

Albumin levels were measured in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples using an ELISA kit (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Isolation and culture of murine alveolar macrophages

Alveolar macrophages were isolated from mice as previously described (36). Briefly, mice were euthanized, and BAL cultures were performed 6 h after i.n. administration of sterile PBS or P. aeruginosa; 1 ml of PBS was gently infused into the lung via an angiocatheter inserted into the trachea. The lavage was then withdrawn with a 1-ml syringe, and this process was repeated 20 times. The lavages were combined and centrifuged at 400 g for 3 min. The BAL cells were resuspended in PBS and counted with a hemocytometer. Equal numbers of cells were seeded in 6-well plates with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the cells were cultured in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1 h. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing the dishes 3 times with sterile PBS (37). The attached alveolar macrophages were scraped and used for RNA extraction. Approximately 95% of the harvested cells were alveolar macrophages, as confirmed by flow cytometry.

Epididymal fat dissection

Epididymal fat dissection was performed as previously described (38). Briefly, the fat pad was dissected from the left epididymis and then moved into a preweighed tube (W1). The tube and fat pad were weighed together (W2). The fat pad weight (W3) was calculated as follows: W3 = W2 − W1.

Immunostaining of mouse lung sections

Immunohistochemistry and double immunofluorescence were performed as previously described (9, 39). Briefly, lungs removed from uninfected mice or mice infected with P. aeruginosa were inflated to 25 cmH2O pressure, fixed in 10% formalin overnight, embedded in paraffin, and then, sectioned. Lung sections were deparaffinized and incubated with rabbit anti-FABP4 IgG (Ab13979; Abcam) and diluted 1:50 in PBS containing 5% normal horse serum for 18 h at 4°C. The slides were washed in PBS and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to biotin, followed by avidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The signals were developed with a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and the lung sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Omission of the primary antibody and use of FABP4−/− lung sections served as negative controls. For double immunofluorescence, primary antibodies were anti-FABP4 (Ab13979; Abcam) and rat anti-mouse anti-F4/80 (1:50; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Antigen retrieval was performed with citrate pH 6 buffer at 95°C for 10 min before primary antibody incubation. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing in PBS, sections were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and viewed under an Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were captured with NIS-Elements Basic Research software (Nikon).

Real-time RT-PCR

Relative steady-state mRNA expression levels of various genes were assessed by real-time RT-PCR as previously described (8). Lung tissues and alveolar macrophages were harvested at 6 or 24 h after infection from mice that were treated with 2 × 108 CFUs of P. aeruginosa or PBS. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with the First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR amplification assays were performed with CYBR green master mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the ABI Prism 9700 Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. An 18S RNA was used for normalization, and fold change in gene expression was calculated using the comparative threshold method as 2−ΔΔCt.

Quantification of protein levels in BALF, plasma, and lung homogenates

BALF samples, plasma, and lungs were harvested from control and infected mice and stored at −80°C. Lungs were homogenized in RIPA buffer before use. Commercially available ELISA kits were used to quantify the levels of FABP4 (MBL International, Woburn, MA, USA), TNF-α (Thermo Fisher Scientific), IL-6 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), IL-1β (Thermo Fisher Scientific), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), CXCL2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Flow cytometry

Enumeration of all leukocyte (CD45+ leukocytes), polymorphonuclear neutrophil (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G+), and macrophage (CD45+CD11c+SiglecF+MHCIIint) populations were performed as previously described (40). Briefly, lungs were harvested 24 h after i.n. instillation of P. aeruginosa and were digested with type IV collagenase (300 U/ml) and DNase (100 U/ml) in PBS at 37°C for 1 h. The cell suspension was filtered with a 100-µm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min. The cells were washed twice in fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA) and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were quantified using a fluorescence-activated cell sorting Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed on FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). The antibodies used were rat anti-CD45 IgG conjugated to PECy7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:2100 dilution, rat anti-CD11b IgG conjugated to PerCP (BD Biosciences) at a 1:100 dilution, American hamster anti-CD11c conjugated to allophycocyanin (BD Biosciences) at a 1:200 dilution, rat anti-Ly6C conjugated to FITC (BD Biosciences) at a 1:100 dilution, rat anti-Ly6G IgG conjugated to PE (BD Biosciences) at a 1:200 dilution, rat anti-SiglecF IgG conjugated to PE (BD Biosciences) at a 1:50 dilution, and rat anti–major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II IgG conjugated to FITC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:75 dilution.

Generation of FABP4–BM chimeric mice

WT and FABP4−/− recipient mice, at 6–8 wk old, were irradiated twice with 450 cGy irradiation doses 4 h apart. BM was isolated from WT or FABP4−/− donor mice, and 2 × 106 BM cells were injected into tail veins of the recipient mice in a 50-µl volume of LPS-free normal saline solution. Mice were housed for 8–10 wk to permit engraftment of BM cells (36, 41). Four groups of chimeric mice (WT donor into WT recipient, FABP4−/− donor into FABP4−/− recipient, WT donor into FABP4−/− recipient, and FABP4−/− donor into WT recipient) were infected with 2 × 108 or 2 × 109 CFUs of P. aeruginosa i.n. Survival, lung bacterial burdens, and plasma FABP4 levels were determined.

In vitro bactericidal activity of macrophages against P. aeruginosa

The in vitro bactericidal assay was adapted from a previously published protocol from Morissette et al. (42). Briefly, alveolar macrophages were pretreated with LPS (25 ng/ml) overnight and then incubated with bacteria in 2-ml microcentrifuge tubes at a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 5:1 at 37°C for 90 min. After infection, the tubes were centrifuged, and the supernatant was removed. The cell pellet was washed twice with PBS to remove nonphagocytosed bacteria. The number of intracellular, viable bacteria was determined by lysing infected macrophages with a sterile solution of 0.01% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in distilled water for 10 min, and then, 10-fold serial dilutions were made in PBS; 10 μl of diluted samples were stripped on the lysogeny broth agar plates. CFU was determined after incubation at 37°C overnight.

CXCL1 reconstitution

Mice were given 4 µg recombinant murine CXCL1 (rCXCL1; PeproTech) in 30 µl PBS or PBS alone i.n. 30 min before induction of P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are presented as means ± sem. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to show survival over time, and differences between curves were analyzed with the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. For other measurements, statistical significance was determined by Mann-Whitney nonparametric t tests. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

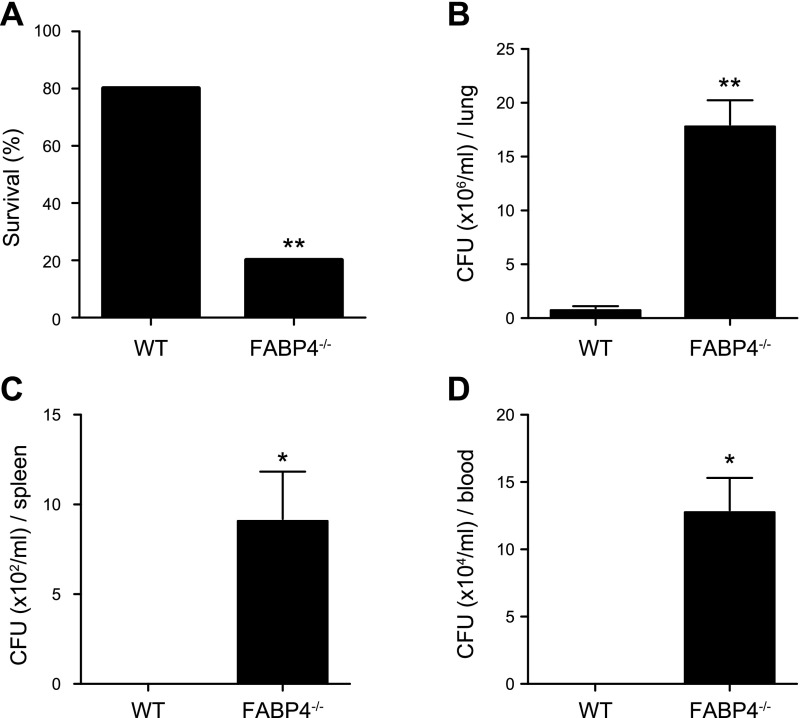

FABP4−/− mice demonstrate increased mortality and decreased bacterial clearance in P. aeruginosa pneumonia

To determine whether FABP4 has a role in the regulation of host responses during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, WT and FABP4−/− mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 109 CFU of P. aeruginosa, and survival was monitored. At 24 h after infection, ∼80% of the WT and 20% of the FAPB4−/− mice were alive (Fig. 1A). To determine whether the increased mortality observed in FABP4−/− mice was due to their reduced capacity to clear P. aeruginosa, bacterial burdens were measured in lung, spleen, and blood samples 24 h after infection. Lung bacterial burden in FABP4−/− mice were 18-fold greater than those in WT mice after P. aeruginosa challenge (Fig. 1B). FAPB4−/− mice also had significantly greater bacterial burden in their spleen and blood samples than WT mice had (Fig. 1C, D). These findings indicate that FABP4 enhances survival and bacterial clearance during P. aeruginosa pneumonia in mice.

Figure 1.

FABP4−/− mice demonstrate increased mortality and decreased bacterial clearance in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. A) C57BL/6 WT and FABP4−/− mice were i.n. infected with 2 × 109 CFUs P. aeruginosa, and survival was monitored ≤3 d, n = 15 mice/group (P = 0.0012). B–D) Bacterial burdens in the lung (B), spleen (C), and blood (D) were assessed 24 h after infection (n = 5/group). Data are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

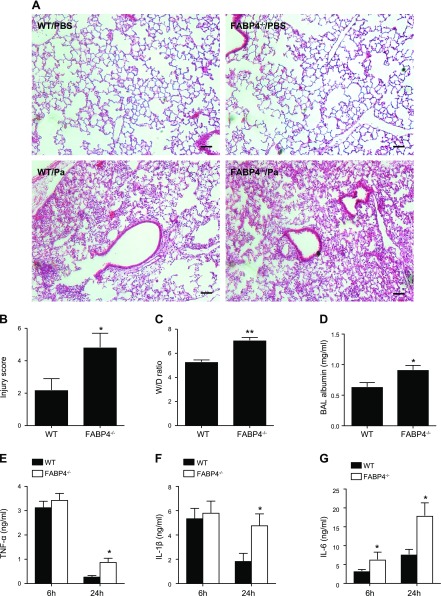

P. aeruginosa pneumonia results in worse ALI in FABP4−/− mice

To begin to delineate the mechanisms by which FABP4 confers protection in P. aeruginosa pneumonia, we examined the histology and other markers of ALI, including alveolar–capillary barrier injury and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the airways and lungs of P. aeruginosa–infected WT vs. FABP4−/− mice. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained lung sections demonstrated no lung inflammation in control WT and control FABP4−/− lungs, but greater neutrophil-predominant inflammatory cell infiltrates in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice at 24 h after infection (Fig. 2A). Blinded scoring of ALI by a senior pathologist (L.K.) revealed higher ALI scores in P. aeruginosa–infected FABP4−/− mice compared with P. aeruginosa–infected WT mice (Fig. 2B). Wet-to-dry lung weight ratios and BALF albumin concentration, markers of increased alveolar capillary barrier permeability, were also significantly higher in P. aeruginosa–infected FABP4−/− mice compared with P. aeruginosa–infected WT mice (Fig. 2C, D). We also measured the levels of key proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) in BALF from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice. At 6 h after infection, TNF-α and IL-1β levels were similar in WT and FABP4−/− mice, whereas IL-6 levels were significantly higher in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2E–G). However, at 24 h after infection, the levels of all these cytokines were significantly higher in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2E–G). Taken together, these data demonstrate that FABP4−/− mice exhibited greater ALI and lung inflammation 24 h after the induction of P. aeruginosa pneumonia compared with WT mice.

Figure 2.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia results in worse ALI in FABP4−/− mice. C57BL/6 WT and FABP4−/− mice were i.n. infected with 2 × 108 CFUs P. aeruginosa, and ALI was assessed 24 h later (n = 5–9/group). A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained control and P. aeruginosa–infected (Pa) lungs 24 h after infection are shown. Scale bars, 50 µm. B) Lung injury scores were determined by a senior pathologist (L.K.) blinded to the genotypes and treatment, based on the presence of interstitial inflammation, alveolar inflammation, pleuritis, bronchitis, and vasculitis. C–G) Wet-to-dry lung-weight ratios (C) and BAL albumin levels (D) 24 h after infection are shown. TNF-α (E), IL-1β (F), and IL-6 (G) protein levels in BALF obtained 6 or 24 h after infection from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

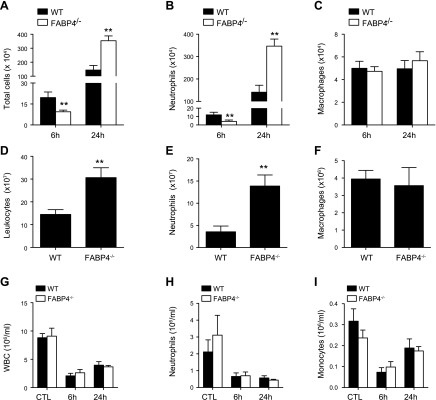

FABP4−/− mice have impaired early neutrophil accumulation in the lung during P. aeruginosa pneumonia

To further characterize the inflammatory responses of FABP4−/− mice during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, BAL cells were enumerated at 6 and 24 h after infection. The total number of leukocytes and neutrophils was significantly lower (∼40%) at 6 h after infection but was significantly higher (∼240%) at 24 h after infection in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A, B). In contrast, the number of lung macrophages was similar in the 2 groups at both times (Fig. 3C). In complementary studies, leukocytes in enzymatic digests of whole lungs from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h after infection. Consistent with the results of histopathology and BALF cell counts, there were significantly more total lung neutrophil numbers in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice, whereas macrophage numbers were similar in both groups at 24 h after infection (Fig. 3D–F). These data indicate that FABP4−/− mice have defective early neutrophil accumulation in their lungs during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, followed by heightened accumulation of neutrophils at 24 h after infection. Because complete blood cell and differential blood leukocyte counts of FABP4−/− and WT mice were similar before and after infection (Fig. 3G–I), the altered neutrophil accumulation in FABP4−/− lungs is unlikely to be secondary to a defect in neutrophil production or mobilization from the BM.

Figure 3.

FABP4−/− mice have impaired early neutrophil accumulation in the lung during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. C57BL/6 WT and FABP4−/− mice were i.n. infected with 2 × 108 CFUs on live P. aeruginosa (n = 8–12/group). BALF samples were collected 6 and 24 h after infection. A–F) Total cells (A), neutrophils (B), and macrophages (C) were quantified in BALF samples. In another cohort of P. aeruginosa–infected mice (n = 5/group), lung homogenates were analyzed by flow cytometry and total number of leukocytes (CD45+) (D), neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G+) (E), and macrophages (CD45+CD11c+SiglecF+MHCIIint) (F) were determined. G–I) Terminal blood collection was performed by cardiac puncture 6 and 24 h after infection from WT and FABP4−/− mice with P. aeruginosa pneumonia for complete blood cell and differential blood counts (n = 5–8/group). Data are presented as means ± sem. **P < 0.01.

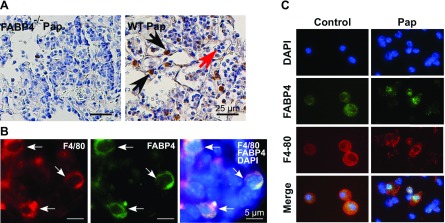

FABP4 is expressed in macrophages in P. aeruginosa–infected lungs

To identify the cell types that express FABP4 in murine lungs during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, lungs were harvested from P. aeruginosa–infected WT mice 24 h after infection, and immunohistochemistry was performed with an anti-FABP4 antibody, the specificity of which has been previously verified in our laboratory (2). Consistent with our previous studies, FABP4 immunoreactivity was detected in macrophages but not in neutrophils in either control or P. aeruginosa–infected lungs (Fig. 4A) (2, 4, 20). The expression of FABP4 in macrophages in P. aeruginosa–infected murine lungs was confirmed by double-immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies against the macrophage marker F4/80 and FABP4 (Fig. 4B). Next, to confirm the expression of FABP4 in alveolar macrophages, WT mice were given i.n. PBS or P. aeruginosa bacteria, and BAL cultures were performed 6 h after infection. Double-immunofluorescence analysis of cytospins stained with F4/80 and FABP4 antibodies verified FABP4 expression in alveolar macrophages but not in any other cell types in BALF samples (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

FABP4 is expressed in macrophages in P. aeruginosa–infected lungs. A, B) Immunohistochemistry for FABP4 (A) and double-immunofluorescence analysis for F4/80 and FABP4 (B) was performed on P. aeruginosa–infected FABP4−/− and WT murine lung sections 24 h after infection. C) Double-immunofluorescence analysis for F4/80 and FABP4 was performed on cytospins of BALF harvested from control and P. aeruginosa–infected WT (Pap) mice 6 h after infection. Representative images are shown (n = 3–5/group).

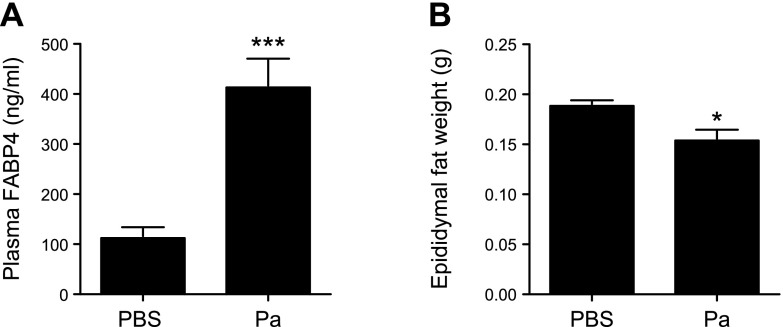

Plasma FABP4 levels are increased during P. aeruginosa pneumonia in mice

Plasma levels of FABP4 are increased in several metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, including type 2 diabetes (14). To determine whether P. aeruginosa infection causes any alterations in circulating levels of FABP4, FABP4 levels were measured in plasma samples from WT mice 24 h after i.n. administration of P. aeruginosa or PBS and were significantly higher in P. aeruginosa–infected mice compared with control mice (Fig. 5A). Because previous studies have demonstrated that plasma FABP4 is primarily derived from adipocytes in response to lipolytic signals (10) and early sepsis is associated with accelerated lipolysis (43), we next investigated whether there was evidence of lipolysis in the murine P. aeruginosa pneumonia model by measuring the weight of epididymal white adipose tissue as a surrogate for adipocyte mass (44). We found a significant decrease in epididymal white adipose tissue in WT mice with P. aeruginosa pneumonia compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Taken together, these data indicated that plasma FABP4 levels are increased during P. aeruginosa pneumonia and are associated with increased lipolysis.

Figure 5.

Plasma FABP4 levels are increased during P. aeruginosa pneumonia in mice. WT mice were given i.n. PBS (n = 5) or 2 × 108 CFUs of live P. aeruginosa (n = 10; Pa). A) Blood was collected 24 h later, and plasma FABP4 levels were measured using ELISA. B) Fat pads from the left epididymis of control and P. aeruginosa–infected mice were dissected and weighed (n = 6/group). Data are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

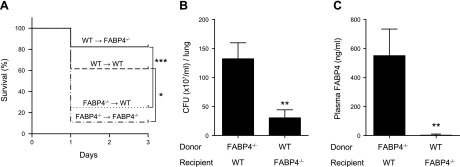

Macrophage-derived FABP4 provides protection in P. aeruginosa pneumonia

We detected FABP4 in lung macrophages (Fig. 4) and found elevated levels of plasma FABP4 (Fig. 5) during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. To determine the contribution of FABP4 derived from macrophages vs. other cellular sources vs. plasma FABP4 to host defense during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, FABP4 BM chimeras and appropriate controls were generated by transplanting WT and FABP4−/− BM into WT or FABP4−/− recipient mice. FABP4 BM chimeric mice were challenged with i.n. P. aeruginosa, and survival was recorded 24 h later. The survival of WT recipients with FABP4−/− BM was significantly lower than WT recipients with WT BM and was comparable to the survival of FABP4−/− recipients with FABP4−/− BM (Fig. 6A). The survival of FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM was significantly greater than that of FABP4−/− recipients with FABP4−/− BM and was comparable to that of WT recipients with WT BM (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that hematopoietic cells (likely macrophages, because FABP4 is not expressed in any other hematopoietic cells) are the major source of protective FABP4 during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. This conclusion was further supported by the finding of significantly decreased lung bacterial burdens in FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM compared with WT recipients with FABP4−/− BM cells (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, plasma FABP4 levels were nearly undetectable in FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM (Fig. 6C). This finding is in agreement with those from a previous study (10) and indicates that circulating FABP4 is not derived from hematopoietic cells/macrophages and does not have a role in host defense against P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Taken together, these results demonstrate that macrophages are the main cellular source of protective FABP4 during P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

Figure 6.

Macrophage-derived FABP4 provides protection in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. WT and FABP4−/− recipient mice were irradiated. BM was isolated from WT or FABP4−/− donor mice, and 2 × 106 BM cells were injected into tail veins of the recipient mice. Mice were infected i.n. with P. aeruginosa 8–10 wk after BM transplant. A) Kaplan-Meier survival plots are shown for FABP4 chimeric mice [WT recipients with WT BM cells (WT → WT, n = 26), WT recipients with FABP4−/− BM cells (FABP4−/− → WT, n = 28), FABP4−/− recipients with FABP4−/− BM cells (FABP4−/− → FABP4−/−, n = 9), and FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM cells (WT → FABP4−/−, n = 16)]. Combined survival curves were compared by Mantel-Cox log-rank test. B) Lung bacterial burdens of WT recipients with FABP4−/− BM cells and FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM cells were assessed 24 h after infection. C) Plasma FABP4 levels of WT recipients with FABP4−/− BM cells and FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM cells were measured 24 h after infection. Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

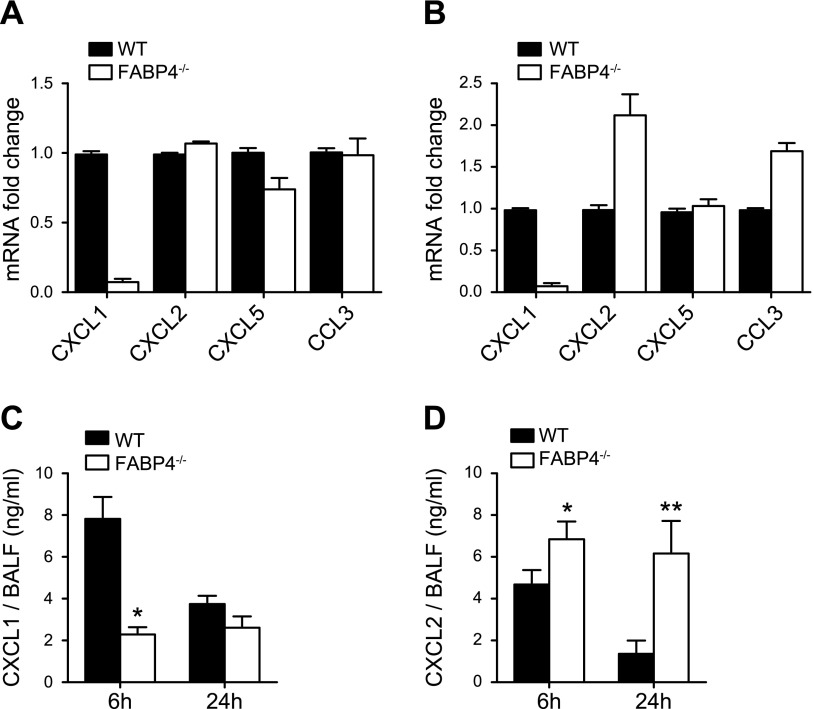

FABP4 deficiency is associated with impaired macrophage-CXCL1 production and decreased BALF CXCL1 levels during P. aeruginosa pneumonia

To determine the mechanism or mechanisms by which macrophage-FABP4 enhances host protection during P. aeruginosa pneumonia, we first investigated whether FABP4 regulates bacterial killing by macrophages. Alveolar macrophages isolated from FABP4−/− and WT mice were incubated with P. aeruginosa in vitro at 1 multiplicity of infection, and bacterial survival was assessed 90 min later. There were no significant differences in bacterial killing of P. aeruginosa mediated by FABP4−/− and WT alveolar macrophages (27 ± 5% vs. 37 ± 3%, n = 6 independent experiments). This result was in accordance with previous studies showing that macrophage killing of P. aeruginosa does not substantially contribute to the outcome of that infection (42).

Those observations coupled with attenuated early neutrophil accumulation in FABP4−/− murine lungs during P. aeruginosa pneumonia suggested that macrophage-FABP4 could enhance host defense by increasing the production of neutrophil chemoattractants by macrophages. Because we did not find any major differences in BALF levels of TNF-α or IL-1β (Fig. 2), 2 major cytokines that promote early neutrophil recruitment during infections, between FABP4−/− and WT mice 6 h after infection, we next assessed the expression of a panel of chemokines by alveolar macrophages isolated from P. aeruginosa–infected FABP4−/− and WT mice 6 h after infection. FABP4−/− alveolar macrophages had ∼10-fold lower CXCL1 mRNA levels than the alveolar macrophage levels in WT mice, whereas the mRNA levels of other chemokines (CXCL2, CCL3, and CXCL5) were essentially similar in FABP4−/− and WT alveolar macrophages (Fig. 7A). As an independent confirmation of positive regulation of CXCL1 by FABP4 in alveolar macrophages, we treated alveolar macrophages from uninfected WT and FABP4−/− mice with LPS in vitro and assessed gene expression levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL3, and CXCL5. In agreement with the results from our in vivo infection model obtained from P. aeruginosa–infected alveolar macrophages, CXCL1 mRNA levels were 20-fold lower in LPS-treated FABP4−/− alveolar macrophages than they were in LPS-treated WT alveolar macrophages (Fig. 7B). In contrast, CXCL2 and CCL3 mRNA levels were ∼2-fold higher in FABP4−/− alveolar macrophages vs. WT alveolar macrophages, and CXCL5 mRNA levels were similar in LPS-treated FABP4−/− and WT alveolar macrophages.

Figure 7.

Macrophage-FABP4 is a key regulator of CXCL1 production during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. A) Alveolar macrophages were isolated from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice 6 h after infection. Relative mRNA levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, and CCL3 were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Means ± sem from 2 independent experiments are shown. B) Alveolar macrophages were isolated from WT and FABP4−/− mice and were treated with 100 ng/ml P. aeruginosa LPS for 6 h. Relative mRNA levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, and CCL3 were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Means ± sem from 2 independent experiments are shown. C) CXCL1 protein levels in BALF from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice 6 or 24 h after infection were measured by ELISA (n = 5–8). D) CXCL2 protein levels in BALF from P. aeruginosa–infected WT and FABP4−/− mice 6 or 24 h after infection were measured by ELISA (n = 5–8). Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CXCL1 is a key neutrophil chemoattractant and is produced by other cell types, such as epithelial cells and neutrophils, in addition to macrophages during bacterial pneumonia (45). To determine whether CXCL1 protein levels were also lower in the FABP4−/− airways, we measured BALF CXCL1 levels in P. aeruginosa–infected FABP4−/− and WT mice. The BALF CXCL1 levels were 3-fold lower in FABP4−/− mice compared with WT mice at 6 h after infection (Fig. 7C). However, at 24 h after infection, airway CXCL1 levels were similar in infected FABP4−/− and WT mice, likely because of subsequent production of CXCL1 by cell types other than macrophages (such as epithelial cells, which do not express FABP4). In contrast to CXCL1, CXCL2 levels were 25 and 300% higher at 6 and 24 h, after infection, respectively, in FABP4−/− BALF compared with WT BALF (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that a later compensatory surge in CXCL2 levels likely contributes to the enhanced accumulation of neutrophils in FABP4−/− airways and lungs 24 h after the onset of P. aeruginosa infection.

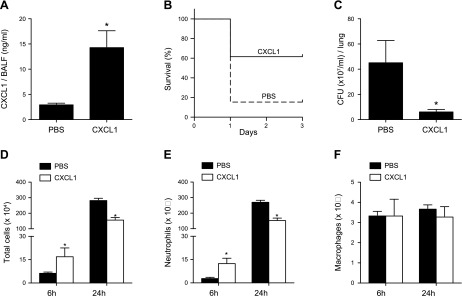

Reconstitution of CXCL1 levels in the airways protects FABP4−/− mice from increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa pneumonia

To investigate the role of decreased airway CXCL1 levels in increasing the susceptibility of FABP4−/− mice to P. aeruginosa pneumonia, FABP4−/− mice were given i.n., endotoxin-free PBS or rCXCL1 protein, followed by P. aeruginosa bacteria 30 min later. BALF CXCL1 levels were measured 6 h after infection and were found to be significantly higher in the rCXCL1 treatment group, with mean CXCL1 levels of 15 ng/ml, compared with PBS-treated mice (Fig. 8A). rCXCL1-treated FABP4−/− mice had improved survival (60 vs. 20%) at 24 h (Fig. 8B) and lower lung bacterial burdens (Fig. 8C) than PBS-treated FABP4−/− mice had (20%) (Fig. 8C). To determine whether the protective effect of CXCL1 was due to improved early neutrophil accumulation in the lungs, BALF leukocytes were enumerated 6 and 24 h after infection. BALF from rCXCL1-treated FABP4−/− mice had significantly higher total leukocyte and neutrophil counts at 6 h after infection, but lower total leukocyte and neutrophil counts at 24 h after infection compared with PBS-treated FABP4−/− mice (Fig. 8D, E). The macrophage numbers were similar between the 2 groups at both times (Fig. 8F). Thus, reconstitution of airway CXCL1 levels restored both the impaired early and enhanced late neutrophil accumulation in FABP4−/− lungs. These data indicate that increased susceptibility of FABP4−/− mice to P. aeruginosa pneumonia is, in large part, due to lower CXCL1 levels in the airways during the early stages of infection. Thus, macrophage-derived FABP4 contributes to host defense by up-regulating macrophage-CXCL1 production, which enhances early neutrophil recruitment, during P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

Figure 8.

Airway CXCL1 reconstitution protects FABP4−/− mice from increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa pneumonia. PBS or recombinant CXCL1 protein was instilled i.n. 30 min before P. aeruginosa infection. A) BALF from P. aeruginosa–infected mice was collected 6 h after infection, and CXCL1 levels were measured. B) Kaplan-Meier survival plots are shown for 13 mice/group (P = 0.02). C) Lung bacterial burdens were measured 24 h after infection. D–F) BALF was performed at 6 and 24 h postinfection and total cells (D), neutrophils (E), and macrophages (F) were enumerated. Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Although many bacterial pathogens primarily elicit a neutrophil response to lung infection and the role of alveolar macrophages can be difficult to discern against the backdrop of massive neutrophil influx, numerous studies indicate macrophage responses are key to coordinating the overall host response to bacterial lung infection (32, 46, 47). To our knowledge, the role of macrophage-FABP4 in pulmonary bacterial infections has not been previously described. In this study, we found that FABP4−/− mice demonstrate increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa pneumonia, and we identified a novel role for macrophage-derived FABP4 in promoting host defense against that infection.

Our initial studies demonstrated impaired neutrophil accumulation in FABP4−/− mice during the early stages of P. aeruginosa pneumonia, which was associated with diminished bacterial clearance and increased mortality. Those observations highlighted the importance of early neutrophil responses in bacterial clearance during acute P. aeruginosa pneumonia and suggested that FABP4 regulated that critical process. Experiments using FABP4 BM chimeras demonstrated that the main cellular source of FABP4 that provided protection against P. aeruginosa was the hematopoietic cells, rather than resident cells, such as adipocytes or endothelial cells. Because macrophages are the only hematopoietic cells that express FABP4, those results led us to focus on pulmonary macrophages to determine the mechanism of protection afforded by FABP4 in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Previous in vitro studies have shown that FABP4-deficient macrophage cell lines exhibit decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines when activated (7). However, in the airway milieu, FABP4−/− mice had comparable or even slightly higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines compared with WT mice during early stages of the infection, suggesting that the macrophage-FABP4 did not have a role in modulating the total levels of those cytokines in the airways during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Indeed, subsequently, in the context of increasing neutrophil accumulation, ALI, and acute lung inflammation 24 h after infection, FABP4−/− BALF samples contained significantly higher levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 compared with that in WT BALF. Interestingly, through a targeted analysis of neutrophil chemoattractants, we identified a profound decrease in the expression level of the CXC-chemokine CXCL1 in FABP4−/− alveolar macrophages compared with WT macrophages at 6 h after infection. There was also a decrease in BALF CXCL1 protein levels in FABP4−/− mice in early stages of P. aeruginosa, which subsequently recovered at 24 h after infection, likely because of the contribution of cells other than macrophages, such as epithelial cells, to CXCL1 levels in the airways during P. aeruginosa infection at that later time. Because FABP4 expression is detected only in macrophages in P. aeruginosa–infected lungs, taken together, those data indicate that macrophages are the likely primary source of CXCL1 during early stages of P. aeruginosa pneumonia. rCXCL1 reconstitution studies restored the morbidity and mortality of FABP4−/− mice in P. aeruginosa pneumonia, thus identifying a novel regulatory axis between macrophage-FABP4 and macrophage-CXCL1 that governs early neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Although detection of FABP4 in alveolar macrophages in control lungs indicated that FABP4 is expressed in resident alveolar macrophages, further studies are needed to determine the macrophage subpopulations, the resident macrophages vs. inflammatory monocyte-derived macrophages, that express FABP4 during pneumonia.

In addition to elucidating a novel role for macrophage-FABP4, these findings have several important implications for our understanding of the pulmonary host defense during P. aeruginosa pneumonia. First, in agreement with previously published studies (48, 49), the findings underscore the critical importance of neutrophil recruitment, especially the requirement for a swift and early influx of neutrophils to the lung, in bacterial clearance during acute P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Second, they provide new evidence for the significance of the crosstalk between macrophages and neutrophils in bacterial clearance and identify macrophage-CXCL1 as a critical mediator downstream of FABP4 in that process. In line with our data, CXCL1 was found to have a key role in host defense against pulmonary Klebsiella pneumoniae infections (45, 50). Furthermore, our findings demonstrate nonredundant roles for CXCL1 and CXCL2 in the murine model of P. aeruginosa pneumonia because CXCL2 levels were not significantly altered in FABP4−/− mice, and decreased CXCL1 levels were sufficient to impair early neutrophil recruitment to the lung. Thus, CXCL1 and CXCL2 appear to be differentially regulated and have distinct roles in the current murine model of P. aeruginosa pneumonia. In a previous study, FABP4-deficient macrophages were found to display reduced levels of IκB kinase and NF-κB activation (7). Although the mechanism or mechanisms by which FABP4 promotes CXCL1 gene expression are not known and requires further study, our results suggest that it is unlikely to be mediated by NF-κB activation because NF-κB is a transcriptional regulator of both CXCL1 and CXCL2 (51).

Serum FABP4 levels were significantly higher in WT mice during P. aeruginosa infection, likely because of increased lipolytic signals, as suggested by the decreased weight of epididymal fat pads consisting of white adipose tissue, which may have resulted in increased secretion of FABP4 from adipocytes (10). Consistent with previous observations (10), we did not detect any circulating FABP4 in FABP4−/− recipients with WT BM, thus confirming the major source of circulating FABP4 as being resident cells. Because these chimeric mice lacking plasma FABP4 did not exhibit increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa pneumonia compared with WT mice with WT BM, we conclude that circulating FABP4 does not have a role in host defense against P. aeruginosa infection. However, based on our observations in the murine model, elevated serum FABP4 levels may serve as a useful marker of pneumonia. Patients with underlying lung disease, such as those with chronic lung disease of prematurity or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, may especially benefit from the availability of such a biomarker for accurate diagnosis of superimposed pneumonia.

In summary, we identified a novel pathway that links macrophage-FABP4 to host defense during pulmonary P. aeruginosa infection via promotion of early macrophage CXCL1 production. Further studies are needed to determine whether the host protection afforded by FABP4 extends to other bacteria and how it may be exploited for translational goals.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Gokhan Hotamisligil (Sabri Ülker Center, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA) for FABP4−/− mice, Dr. Gregory Priebe (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) for helpful discussions, and Meher Iqbal (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) for assistance with immunostaining. This work was supported by the American Heart Association (Grant 11GRNT4900002 to S.C.); the Brigham Research Institute (to S.C.); U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P50 HL107165-01, R21 HL111835, and NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant RO1AI111475 (to C.A.O.); Brigham and Women’s Hospital–Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute Consortium grants (to C.A.O.); and the Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute (Grant CIA 046123 to C.A.O.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ALI

acute lung injury

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BM

bone marrow

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- CXCL1

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1

- FABP4

fatty acid binding protein 4

- i.n.

intranasal(ly)

- rCXCL1

recombinant murine CXCL1

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Cernadas, G. B. Pier, C. A. Owen, H. Christou, and S. Cataltepe designed the research; X. Liang, M. Cernadas, L. Kobzik, C. A. Owen, and S. Cataltepe analyzed the data; X. Liang, K. Gupta, and J. Rojas Quinteros performed the research; and X. Liang, C. A. Owen, and S. Cataltepe wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hertzel A. V., Bernlohr D. A. (2000) The mammalian fatty acid-binding protein multigene family: molecular and genetic insights into function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11, 175–180 10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00257-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmasri H., Karaaslan C., Teper Y., Ghelfi E., Weng M., Ince T. A., Kozakewich H., Bischoff J., Cataltepe S. (2009) Fatty acid binding protein 4 is a target of VEGF and a regulator of cell proliferation in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 23, 3865–3873 10.1096/fj.09-134882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuhashi M., Hotamisligil G. S. (2008) Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 489–503 10.1038/nrd2589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghelfi E., Karaaslan C., Berkelhamer S., Akar S., Kozakewich H., Cataltepe S. (2011) Fatty acid-binding proteins and peribronchial angiogenesis in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 45, 550–556 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0376OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuhashi M., Fucho R., Görgün C. Z., Tuncman G., Cao H., Hotamisligil G. S. (2008) Adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid-binding proteins contribute to metabolic deterioration through actions in both macrophages and adipocytes in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2640–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makowski L., Boord J. B., Maeda K., Babaev V. R., Uysal K. T., Morgan M. A., Parker R. A., Suttles J., Fazio S., Hotamisligil G. S., Linton M. F. (2001) Lack of macrophage fatty-acid-binding protein aP2 protects mice deficient in apolipoprotein E against atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 7, 699–705 10.1038/89076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makowski L., Brittingham K. C., Reynolds J. M., Suttles J., Hotamisligil G. S. (2005) The fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, coordinates macrophage cholesterol trafficking and inflammatory activity. Macrophage expression of aP2 impacts peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and IκB kinase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12888–12895 10.1074/jbc.M413788200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmasri H., Ghelfi E., Yu C. W., Traphagen S., Cernadas M., Cao H., Shi G. P., Plutzky J., Sahin M., Hotamisligil G., Cataltepe S. (2012) Endothelial cell-fatty acid binding protein 4 promotes angiogenesis: role of stem cell factor/c-kit pathway. Angiogenesis 15, 457–468 10.1007/s10456-012-9274-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghelfi E., Yu C. W., Elmasri H., Terwelp M., Lee C. G., Bhandari V., Comhair S. A., Erzurum S. C., Hotamisligil G. S., Elias J. A., Cataltepe S. (2013) Fatty acid binding protein 4 regulates VEGF-induced airway angiogenesis and inflammation in a transgenic mouse model: implications for asthma. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 1425–1433 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao H., Sekiya M., Ertunc M. E., Burak M. F., Mayers J. R., White A., Inouye K., Rickey L. M., Ercal B. C., Furuhashi M., Tuncman G., Hotamisligil G. S. (2013) Adipocyte lipid chaperone AP2 is a secreted adipokine regulating hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 17, 768–778 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burak M. F., Inouye K. E., White A., Lee A., Tuncman G., Calay E. S., Sekiya M., Tirosh A., Eguchi K., Birrane G., Lightwood D., Howells L., Odede G., Hailu H., West S., Garlish R., Neale H., Doyle C., Moore A., Hotamisligil G. S. (2015) Development of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody that targets secreted fatty acid-binding protein aP2 to treat type 2 diabetes. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 319ra205 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac6336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miao X., Wang Y., Wang W., Lv X., Wang M., Yin H. (2015) The mAb against adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein 2E4 attenuates the inflammation in the mouse model of high-fat diet-induced obesity via Toll-like receptor 4 pathway. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 403, 1–9 10.1016/j.mce.2014.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabré A., Babio N., Lázaro I., Bulló M., Garcia-Arellano A., Masana L., Salas-Salvadó J. (2012) FABP4 predicts atherogenic dyslipidemia development. The Predimed study. Atherosclerosis 222, 229–234 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tso A. W., Xu A., Sham P. C., Wat N. M., Wang Y., Fong C. H., Cheung B. M., Janus E. D., Lam K. S. (2007) Serum adipocyte fatty acid binding protein as a new biomarker predicting the development of type 2 diabetes: a 10-year prospective study in a Chinese cohort. Diabetes Care 30, 2667–2672 10.2337/dc07-0413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishimura S., Furuhashi M., Watanabe Y., Hoshina K., Fuseya T., Mita T., Okazaki Y., Koyama M., Tanaka M., Akasaka H., Ohnishi H., Yoshida H., Saitoh S., Miura T. (2013) Circulating levels of fatty acid-binding protein family and metabolic phenotype in the general population. PLoS One 8, e81318 10.1371/journal.pone.0081318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuncman G., Erbay E., Hom X., De Vivo I., Campos H., Rimm E. B., Hotamisligil G. S. (2006) A genetic variant at the fatty acid-binding protein aP2 locus reduces the risk for hypertriglyceridemia, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6970–6975 10.1073/pnas.0602178103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saksi J., Ijäs P., Mäyränpää M. I., Nuotio K., Isoviita P. M., Tuimala J., Lehtonen-Smeds E., Kaste M., Jula A., Sinisalo J., Nieminen M. S., Lokki M. L., Perola M., Havulinna A. S., Salomaa V., Kettunen J., Jauhiainen M., Kovanen P. T., Lindsberg P. J. (2014) Low-expression variant of fatty acid-binding protein 4 favors reduced manifestations of atherosclerotic disease and increased plaque stability. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 7, 588–598 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman S. L., Park Y. K., Lee J. Y. (2011) Unsaturated fatty acids repress the expression of adipocyte fatty acid binding protein via the modulation of histone deacetylation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Eur. J. Nutr. 50, 323–330 10.1007/s00394-010-0140-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Y., Luo N., Lopes-Virella M. F., Garvey W. T. (2002) The adipocyte lipid binding protein (ALBP/aP2) gene facilitates foam cell formation in human THP-1 macrophages. Atherosclerosis 165, 259–269 10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00305-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gautier E. L., Chow A., Spanbroek R., Marcelin G., Greter M., Jakubzick C., Bogunovic M., Leboeuf M., van Rooijen N., Habenicht A. J., Merad M., Randolph G. J. (2012) Systemic analysis of PPARγ in mouse macrophage populations reveals marked diversity in expression with critical roles in resolution of inflammation and airway immunity. J. Immunol. 189, 2614–2624 10.4049/jimmunol.1200495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuhashi M., Tuncman G., Görgün C. Z., Makowski L., Atsumi G., Vaillancourt E., Kono K., Babaev V. R., Fazio S., Linton M. F., Sulsky R., Robl J. A., Parker R. A., Hotamisligil G. S. (2007) Treatment of diabetes and atherosclerosis by inhibiting fatty-acid-binding protein aP2. Nature 447, 959–965 10.1038/nature05844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boord J. B., Maeda K., Makowski L., Babaev V. R., Fazio S., Linton M. F., Hotamisligil G. S. (2002) Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, alters late atherosclerotic lesion formation in severe hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 1686–1691 10.1161/01.ATV.0000033090.81345.E6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneberger D., Aharonson-Raz K., Singh B. (2011) Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity and Toll-like receptors in the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 343, 97–106 10.1007/s00441-010-1032-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne A. J., Mathie S. A., Gregory L. G., Lloyd C. M. (2015) Pulmonary macrophages: key players in the innate defence of the airways. Thorax 70, 1189–1196 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent J. L., Rello J., Marshall J., Silva E., Anzueto A., Martin C. D., Moreno R., Lipman J., Gomersall C., Sakr Y., Reinhart K.; EPIC II Group of Investigators (2009) International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302, 2323–2329 10.1001/jama.2009.1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rello J., Borgatta B., Lisboa T. (2013) Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in the early twenty-first century. Intensive Care Med. 39, 2204–2206 10.1007/s00134-013-3046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson R., Sethi S., Anzueto A., Miravitlles M. (2013) Antibiotics for treatment and prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Infect. 67, 497–515 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaspar M. C., Couet W., Olivier J. C., Pais A. A., Sousa J. J. (2013) Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis lung disease and new perspectives of treatment: a review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32, 1231–1252 10.1007/s10096-013-1876-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun H. Y., Fujitani S., Quintiliani R., Yu V. L. (2011) Pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: part II: antimicrobial resistance, pharmacodynamic concepts, and antibiotic therapy. Chest 139, 1172–1185 10.1378/chest.10-0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujitani S., Sun H. Y., Yu V. L., Weingarten J. A. (2011) Pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: part I: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and source. Chest 139, 909–919 10.1378/chest.10-0166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashimoto S., Pittet J. F., Hong K., Folkesson H., Bagby G., Kobzik L., Frevert C., Watanabe K., Tsurufuji S., Wiener-Kronish J. (1996) Depletion of alveolar macrophages decreases neutrophil chemotaxis to Pseudomonas airspace infections. Am. J. Physiol. 270, L819–L828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manicone A. M., Birkland T. P., Lin M., Betsuyaku T., van Rooijen N., Lohi J., Keski-Oja J., Wang Y., Skerrett S. J., Parks W. C. (2009) Epilysin (MMP-28) restrains early macrophage recruitment in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J. Immunol. 182, 3866–3876 10.4049/jimmunol.0713949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kooguchi K., Hashimoto S., Kobayashi A., Kitamura Y., Kudoh I., Wiener-Kronish J., Sawa T. (1998) Role of alveolar macrophages in initiation and regulation of inflammation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 66, 3164–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotamisligil G. S., Johnson R. S., Distel R. J., Ellis R., Papaioannou V. E., Spiegelman B. M. (1996) Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science 274, 1377–1379 10.1126/science.274.5291.1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh S., Gregory D., Smith A., Kobzik L. (2011) MARCO regulates early inflammatory responses against influenza: a useful macrophage function with adverse outcome. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 45, 1036–1044 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0349OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knolle M. D., Nakajima T., Hergrueter A., Gupta K., Polverino F., Craig V. J., Fyfe S. E., Zahid M., Permaul P., Cernadas M., Montano G., Tesfaigzi Y., Sholl L., Kobzik L., Israel E., Owen C. A. (2013) Adam8 limits the development of allergic airway inflammation in mice. J. Immunol. 190, 6434–6449 10.4049/jimmunol.1202329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y., Li X., Carpinteiro A., Goettel J. A., Soddemann M., Gulbins E. (2011) Kinase suppressor of Ras-1 protects against pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Nat. Med. 17, 341–346 10.1038/nm.2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugii S., Kida Y., Berggren W. T., Evans R. M. (2011) Feeder-dependent and feeder-independent iPS cell derivation from human and mouse adipose stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 6, 346–358 10.1038/nprot.2010.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cataltepe S., Arikan M. C., Liang X., Smith T. W., Cataltepe O. (2015) Fatty acid binding protein 4 expression in cerebral vascular malformations: implications for vascular remodelling. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 41, 646–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Misharin A. V., Morales-Nebreda L., Mutlu G. M., Budinger G. R., Perlman H. (2013) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages and dendritic cell subsets in the mouse lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 503–510 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0086MA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matute-Bello G., Lee J. S., Frevert C. W., Liles W. C., Sutlief S., Ballman K., Wong V., Selk A., Martin T. R. (2004) Optimal timing to repopulation of resident alveolar macrophages with donor cells following total body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation in mice. J. Immunol. Methods 292, 25–34 10.1016/j.jim.2004.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morissette C., Francoeur C., Darmond-Zwaig C., Gervais F. (1996) Lung phagocyte bactericidal function in strains of mice resistant and susceptible to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 64, 4984–4992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rittig N., Bach E., Thomsen H. H., Pedersen S. B., Nielsen T. S., Jørgensen J. O., Jessen N., Møller N. (2016) Regulation of lipolysis and adipose tissue signaling during acute endotoxin-induced inflammation: a human randomized crossover trial. PLoS One 11, e0162167 10.1371/journal.pone.0162167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung Y. W., Ahmad F., Tang Y., Hockman S. C., Kee H. J., Berger K., Guirguis E., Choi Y. H., Schimel D. M., Aponte A. M., Park S., Degerman E., Manganiello V. C. (2017) White to beige conversion in PDE3B KO adipose tissue through activation of AMPK signaling and mitochondrial function. Sci. Rep. 7, 40445 10.1038/srep40445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai S., Batra S., Lira S. A., Kolls J. K., Jeyaseelan S. (2010) CXCL1 regulates pulmonary host defense to Klebsiella infection via CXCL2, CXCL5, NF-κB, and MAPKs. J. Immunol. 185, 6214–6225 10.4049/jimmunol.0903843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arredouani M., Yang Z., Ning Y., Qin G., Soininen R., Tryggvason K., Kobzik L. (2004) The scavenger receptor MARCO is required for lung defense against pneumococcal pneumonia and inhaled particles. J. Exp. Med. 200, 267–272 10.1084/jem.20040731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warszawska J. M., Gawish R., Sharif O., Sigel S., Doninger B., Lakovits K., Mesteri I., Nairz M., Boon L., Spiel A., Fuhrmann V., Strobl B., Müller M., Schenk P., Weiss G., Knapp S. (2013) Lipocalin 2 deactivates macrophages and worsens pneumococcal pneumonia outcomes. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3363–3372 10.1172/JCI67911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anas A. A., van Lieshout M. H., Claushuis T. A., de Vos A. F., Florquin S., de Boer O. J., Hou B., Van’t Veer C., van der Poll T. (2016) Lung epithelial MyD88 drives early pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a flagellin dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 311, L219–L228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koh A. Y., Priebe G. P., Ray C., Van Rooijen N., Pier G. B. (2009) Inescapable need for neutrophils as mediators of cellular innate immunity to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 77, 5300–5310 10.1128/IAI.00501-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Batra S., Cai S., Balamayooran G., Jeyaseelan S. (2012) Intrapulmonary administration of leukotriene B(4) augments neutrophil accumulation and responses in the lung to Klebsiella infection in CXCL1 knockout mice. J. Immunol. 188, 3458–3468 10.4049/jimmunol.1101985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amiri K. I., Richmond A. (2003) Fine tuning the transcriptional regulation of the CXCL1 chemokine. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 74, 1–36 10.1016/S0079-6603(03)01009-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.