Despite the increasing reliance on polymyxin antibiotics (polymyxin B and colistin) for treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections, many clinical laboratories are unable to perform susceptibility testing due to the lack of accurate and reliable methods. Although gradient agar diffusion is commonly performed for other antimicrobials, its use for polymyxins is discouraged due to poor performance characteristics.

KEYWORDS: antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, colistin, etest, gradient agar diffusion, Gram-negative bacteria, multidrug resistance, polymyxins

ABSTRACT

Despite the increasing reliance on polymyxin antibiotics (polymyxin B and colistin) for treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections, many clinical laboratories are unable to perform susceptibility testing due to the lack of accurate and reliable methods. Although gradient agar diffusion is commonly performed for other antimicrobials, its use for polymyxins is discouraged due to poor performance characteristics. Performing gradient agar diffusion with calcium enhancement of susceptibility testing media has been shown to improve the identification of polymyxin-resistant isolates with plasmid-mediated resistance (mcr-1). We therefore sought to evaluate the broad clinical applicability of this approach for colistin susceptibility testing by assessing a large and diverse collection of resistant and susceptible patient isolates collected from multiple U.S. medical centers. Among 217 isolates, the overall categorical and essential agreement for calcium-enhanced gradient agar diffusion were 73.7% and 65.5%, respectively, compared to the results for reference broth microdilution. Performance varied significantly by organism group, with agreement being highest for Enterobacterales and lowest for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nevertheless, even for Enterobacterales, there was a high rate of very major errors (9.2%). Performance was similarly poor for calcium-enhanced broth microdilution. While calcium enhancement did allow for more accurate categorization of mcr-1-resistant isolates, there were unacceptably high rates of errors for both susceptible and non-mcr-1-resistant isolates, raising serious doubts about the suitability of these calcium-enhanced methods for routine colistin susceptibility testing in clinical laboratories.

INTRODUCTION

Polymyxin antibiotics (colistin and polymyxin B) have been increasingly relied upon as therapies of last resort for patients with carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections (1). Resistance to polymyxins has become increasingly common, being noted in Klebsiella species (2, 3), Acinetobacter species (4), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5) isolates. Until recently, most acquired resistance was thought to arise from chromosomal changes (6). However, the recognition of plasmid-mediated resistance (7) has further highlighted polymyxin resistance as a growing public health concern. This threat is further compounded by the lack of routinely available and accurate testing methods for polymyxin susceptibility (8). Many clinical laboratories are unable to perform susceptibility testing for colistin or polymyxin B, in large part due to the lack of FDA-cleared tests on commonly used automated systems. While disk diffusion and gradient agar diffusion (Etest) tests are available and still used in some clinical laboratories, published data provide substantial evidence of poor analytic performance (8, 9), and both the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) recommend against their use (10).

High rates of very major errors (VMEs) are a major concern for disk diffusion and gradient agar diffusion tests, and these methods pose a significant risk of failing to detect resistant isolates (11, 12). This is particularly disappointing for gradient agar diffusion, as gradient strips are widely available, simple to set up and interpret, and in contrast to disk diffusion, also provide MICs. Therefore, modifications to the gradient agar diffusion method that would allow for accurate and reliable MIC determination from carbapenem-resistant clinical isolates would be of significant value. Gwozdzinski et al. (13) recently published an approach that adds calcium to the susceptibility testing media (Mueller-Hinton broth and agar [MHB and MHA, respectively]), thus improving the detection of polymyxin resistance in organisms with plasmid-mediated resistance (mcr-1) without overestimating the MICs of susceptible isolates. However, only a relatively small number of susceptible isolates and isolates with non-plasmid-mediated resistance were included in the study, limiting its generalizability.

The colistin testing ad hoc working group (ahWG) was convened by CLSI to address the challenges of polymyxin susceptibility testing and assess promising novel testing methods. We completed a multicenter study to evaluate the colistin broth disk elution (CBDE) and colistin agar test (CAT), which were both provisionally approved in June 2019 for Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa by the CLSI Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Subcommittee (14). Clinical isolates gathered from this multicenter study were made available to members of the ahWG to assess the performance of other novel methods. We therefore sought to further evaluate calcium enhancement (CE) of Mueller-Hinton media with Etest and broth microdilution (BMD) to determine their potential applicability for clinical laboratory testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overall design.

To assess the clinical applicability of calcium-enhanced (CE) Etest and CE-broth microdilution (CE-BMD), a broad range of colistin-intermediate and colistin-resistant clinical isolates were collected from four U.S. academic medical centers (Johns Hopkins University, Mayo Clinic, University of California Los Angeles, and Columbia University Irving Medical Center [CUIMC]), with additional isolates obtained from the CDC and FDA Antimicrobial Resistance (AR) Isolate Bank, JMI Laboratories, and Accelerate Diagnostics (Tucson, AZ). All testing was performed at CUIMC from 13 December 2018 to 14 February 2019. CE-Etest and CE-BMD were compared to reference broth microdilution (rBMD) to assess agreement and error rates. Standard Etest using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) was also performed to further delineate the effects of calcium enhancement versus test method.

Study isolates.

Study isolates were comprised of 87 challenge isolates from the ahWG collection (14) and 140 isolates collected from CUIMC (Table 1). All isolates were obtained from patient samples that had undergone clinical laboratory testing for colistin or polymyxin susceptibility as part of routine care and were selected to represent balanced proportions that were susceptible and resistant to polymyxins. Seven isolates were positive for mcr-1 as determined by laboratory-developed PCR (7), with the remaining resistant isolates being from species with acquired resistance (e.g., Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp., and Acinetobacter spp.); no intrinsically resistant species (e.g., Serratia, Morganella, and Proteus spp.) were evaluated, as these would not be routinely tested in clinical laboratories.

TABLE 1.

Analytic performance of the CE-Etest, CE-BMD, and Etest compared to the results for rBMD

| Methoda | Organism group | Rate of agreement (%) or error [% (no. of isolates whose results were in error/no. of isolates tested)] compared to rBMD resultb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | EA | VME | ME | ||

| CE-Etest | All isolates | 73.7 | 65.4 | 9.7 (11/113) | 44.2 (46/104) |

| Enterobacterales | 94.5 | 79.8 | 8.0 (7/87) | 0 (0/42) | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 87.5 | 70.0 | 10.3 (3/22) | 11.1 (2/18) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6.2 | 4.2 | 0 (0/4) | 100 (44/44) | |

| CE-BMD | All isolates | 76.5 | 58.5 | 5.3 (6/113) | 43.2 (45/104) |

| Enterobacterales | 95.3 | 79.8 | 5.7 (5/87) | 2.4 (1/42) | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 87.5 | 60.0 | 0 (0/22) | 27.7 (5/18) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 16.6 | 10.4 | 25.0 (1/4) | 88.6 (39/44) | |

| Etest | All isolates | 88.5 | 80.2 | 12.4 (14/113) | 10.6 (11/104) |

| Enterobacterales | 97.6 | 86.0 | 3.4 (3/87) | 0 (0/42) | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 72.5 | 55 | 50 (11/22) | 0 (2/18) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 81.3 | 72.9 | 0 (0/4) | 20.5 (9/44) | |

CE-Etest, calcium-enhanced Etest; CE-BMD, calcium-enhanced broth microdilution.

rBMD, reference broth microdilution; CA, categorical agreement; EA, essential agreement; VME, very major error; ME, major error.

Testing methods.

Frozen stock cultures were subcultured onto 5% sheep blood agar plates. For resistant isolates, a colistin disk (BD, Sparks, MD) was added to maintain selective pressure and prevent potential loss of resistance (8). Colonies from around the disk were selected for subculture, from which pure isolated colonies were suspended in sterile saline to generate a single 0.5 McFarland suspension, which was used as the starting inoculum for all testing methods.

rBMD and CE-BMD.

Frozen BMD panels were made by Accelerate Diagnostics with polystyrene trays containing rows of wells with doubling concentrations of colistin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) ranging from 0.25 to 16 μg/ml without polysorbate 80. Two of these rows were used to determine the reference MIC by reference BMD (rBMD) (14). An additional row, which consisted of Sigma Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) in which the calcium content was adjusted to a final concentration of 5 mM, was used to assess the CE-BMD as previously described (13). Each plate contained growth control wells without colistin for each broth preparation, as well as a negative-control well. BMD panels underwent quality control testing with Escherichia coli strain ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain ATCC 27853 prior to being frozen and shipped to CUIMC on dry ice and stored at −80°C prior to use. MICs were determined as the first well that showed no visible growth.

Etest and CE-Etest.

Agar plates for the CE-Etest were prepared and provided by Hardy Diagnostics (Santa Maria, CA) by supplementing calcium chloride dihydrate to Mueller-Hinton agar to achieve a final concentration of 5 mM (13).

From the initial 0.5 McFarland suspension, a sterile swab was used to evenly inoculate the entire surface of a CE-agar plate and a cation-adjusted MHA plate (Hardy Diagnostics) and allowed to dry for 10 min prior to placement of the gradient strip (bioMérieux, Durham, NC). MIC determination was performed by visual interpretation of the intersection of the zone of inhibition with the gradient strip, rounded up to the next highest doubling concentration. Colonies growing within the main zone of inhibition were counted as true growth.

QC testing/isolates.

Quality control (QC) testing was performed on all testing days with Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain ATCC 28753 (CLSI reference range, 0.5 to 4 μg/ml) and Escherichia coli AR Bank strain #0349, an mcr-1-positive strain selected to provide on-scale results of 2 to 4 μg/ml. Study isolate results were only recorded if each daily QC strain provided in-range results.

Data analysis and repeat testing.

CLSI breakpoints were used for determination of categorical agreement (CA; the percentage of isolates that have the same categorical interpretation). Given the lack of a susceptible category, intermediate results were considered susceptible for the performance calculations (14). Accordingly, isolates with a MIC of ≤2 μg/ml were considered susceptible and those with a MIC of ≥4 μg/ml were considered nonsusceptible. CA and essential agreement (EA; the percentage of isolates in which the test method result was not more than 1 doubling dilution different from the reference method result) were compared, and rates of very major errors (VMEs) and major errors (ME) were calculated accordingly.

Testing was also repeated for isolates with >1 skipped well on rBMD or CE-BMD, and isolates were excluded if wells were skipped on repeat testing (15). Repeat testing was also performed by all methods for isolates with categorical disagreement between rBMD and any of the other test methods. If the repeat result confirmed the first result, a categorical error was confirmed; if the repeat result was instead in CA, the isolate was tested a third time, using the modal MIC for the final result.

RESULTS

A total of 229 isolates underwent testing by each method (Table S1 in the supplemental material). There were 12 exclusions, all due to categorical disagreement between the two rBMD media, and thus, a reference MIC could not be established for these isolates. MICs were compared for the remaining 217 isolates, comprised of 129 Enterobacterales, 48 P. aeruginosa, and 40 Acinetobacter species isolates. There were balanced proportions of colistin-resistant (52.1%) and colistin-intermediate (47.9%) isolates.

CE-Etest.

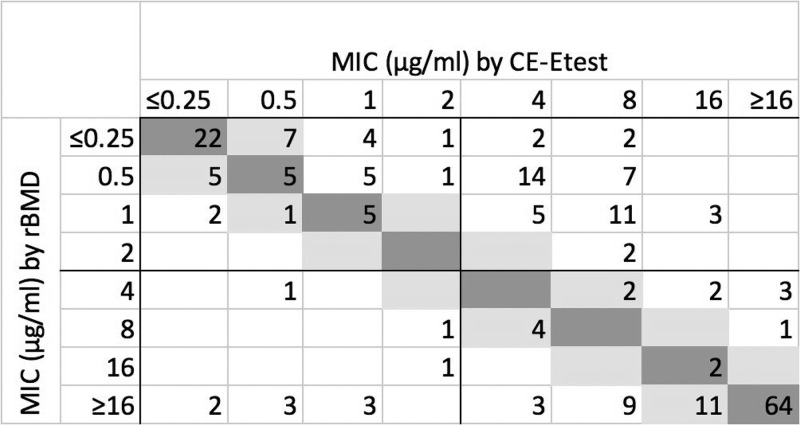

The overall categorical agreement (CA) and essential agreement (EA) for the CE-Etest were 73.7% and 65.5%, respectively (Table 1); there were 11 very major errors (VMEs) (9.7%) and 46 major errors (MEs) (44.2%). Agreement varied significantly by organism group; CA and EA were highest for Enterobacterales isolates, at 93.7% and 79.8%, respectively, and lowest for P. aeruginosa isolates, at 6.2% and 4.2%, respectively. There were high rates of VMEs among Enterobacterales isolates (9.2%) and Acinetobacter species isolates (10.3%) and an extremely high rate of MEs among P. aeruginosa isolates (100%). When considering all isolates, MICs were higher by CE-Etest than by rBMD (Fig. 1). However, this effect was more pronounced for P. aeruginosa isolates than for Acinetobacter or Enterobacterales isolates (Fig. S1A to C). CE-Etest overestimated the reference MIC for nearly all P. aeruginosa isolates but underestimated the reference MIC for some Enterobacterales isolates, including 7 VMEs for isolates for which the MICs were >16 μg/ml by rBMD but ≤0.25 to 1 μg/ml by CE-Etest. MICs for Acinetobacter spp. trended neither higher nor lower than the reference MIC, with both VMEs and MEs seen in >10% of susceptible and resistant isolates, respectively. Calcium supplementation generally led to higher MIC estimation, and MICs were also higher by CE-Etest than by standard Etest, especially for P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species isolates (Fig. S2A to C).

FIG 1.

Scatterplot of MICs by calcium-enhanced Etest (CE-Etest) versus reference broth microdilution (rBMD) for all study isolates (n = 217; numbers in cells show frequency among isolates). Dark gray, absolute agreement; light gray, essential agreement.

mcr-1-positive isolates were more appropriately categorized as resistant by CE-Etest, with MICs that ranged from 2 to 8 μg/ml by rBMD and Etest but increased to 8 to 32 μg/ml by CE-Etest (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MICs for mcr-1-positive isolates

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) ina

: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rBMD | CE-BMD | Etest | CE-Etest | |

| 1 | 4 | >16 | 4 | 16 |

| 2 | 2 | >16 | 2 | 8 |

| 3 | 4 | >16 | 4 | 16 |

| 4 | 4 | >16 | 4 | 32 |

| 5 | 4 | >16 | 4 | 32 |

| 6 | 4 | >16 | 2 | 8 |

| 7 | 4 | >16 | 8 | 8 |

rBMD, reference broth microdilution; CE-BMD, calcium-enhanced broth microdilution; CE-Etest, calcium-enhanced Etest.

CE-BMD.

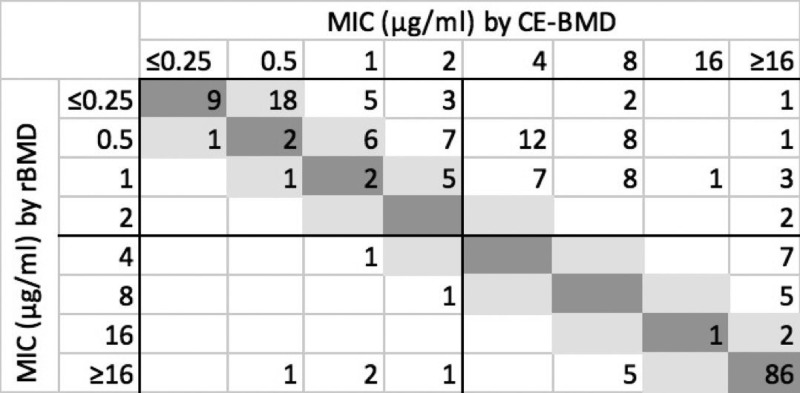

The overall CA and EA for CE-BMD were 76.5% and 58.5%, respectively (Table 1). As with the CE-Etest, performance also varied by organism group, with much higher CA for Enterobacterales (95.3%) and Acinetobacter (87.5%) species isolates than for P. aeruginosa isolates (16.6%). As with CE-Etest, a very high rate of MEs (88.6%) was seen among P. aeruginosa isolates. No VMEs were observed for Acinetobacter species isolates, but there were 5 MEs (27.7%). Calcium enhancement resulted in higher MICs than rBMD (Fig. 2). Although this effect was seen for all three organism groups (Fig. S3A to C), the strongest effect was again seen for P. aeruginosa. Despite this general overestimation effect, as with CE-Etest, there were some Enterobacterales isolates that showed lower MICs with CE-BMD than with rBMD, including 5.7% VMEs (Table 1 and Fig. S3A).

FIG 2.

Scatterplot of MICs by calcium-enhanced broth microdilution (CE-BMD) versus reference broth microdilution (rBMD) for all study isolates (n = 217; numbers in cells show frequency among isolates). Dark gray, absolute agreement; light gray, essential agreement.

As with CE-Etest, mcr-1-positive isolates were also more appropriately categorized as resistant with CE-BMD, with all showing MICs of >16 μg/ml (Table 2).

Etest.

The overall CA and EA for the Etest were 88.5% and 80.2%, respectively (Table 1). Agreement again varied significantly by organism group, with CA highest for Enterobacterales (97.6%) and lowest for Acinetobacter (72.5%) species isolates. Etest overestimated the reference MIC for the majority of P. aeruginosa isolates (Fig. S4C), resulting in 20.5% MEs, whereas Etest underestimated the reference MIC for the majority of Acinetobacter species isolates (Fig. S4B), resulting in 50% VMEs. Surprisingly, Etest showed high agreement with rBMD for Enterobacterales isolates, with CA and EA of 97.6% and 86.0%, respectively, and only 1 VME that was not in EA (Fig. S4A), for an Enterobacter cloacae isolate with a MIC of >6 μg/ml by rBMD but a MIC of <0.25 μg/ml by Etest. There were 2 other VMEs among Enterobacterales isolates, with MICs of 4 μg/ml by rBMD and 2 μg/ml by Etest (thus they were in EA), and no MEs. Almost all isolates with results outside EA had lower MICs by Etest than by rBMD.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated calcium enhancement of colistin susceptibility testing media with the calcium-enhanced (CE) Etest and CE-broth microdilution (CE-BMD) against a large and diverse set of clinical isolates. Both methods showed low overall agreement with reference testing by rBMD, with MICs that often overestimated the MICs by rBMD. Although categorical agreement (CA) for Enterobacterales isolates was >90% for both methods and there was a relatively low rate of majors (MEs), the very major error (VME) rates of 9.2% by CE-Etest and 5.7% by CE-BMD were nevertheless concerning for this group.

Gwozdzinski et al. (13) first reported that CE media enabled more robust identification of colistin-resistant mcr-1-positive isolates. Accordingly, the 7 mcr-1-positive isolates in this study were also more easily identified as resistant with CE-Etest and CE-BMD.

In contrast, whereas the prior study found an overall high rate of agreement for the CE methods, with the rBMD CA rates for CE-Etest and CE-BMD being 100% and 91% for susceptible isolates and 87% and 99% for resistant isolates, we found substantially lower rates of CA in our study. Notably, the prior study did show low essential agreement (EA) for colistin-resistant isolates (less than 25% for both methods), whereas our data showed low EA among both resistant and susceptible isolates. The variability in results between the two studies is most likely attributable to the number and diversity of isolates tested. Gwozdzinski et al. (13) evaluated 65 resistant isolates, 50 of which were mcr-1 mediated, with only 8 having non-mcr acquired resistance and 7 having intrinsic polymyxin resistance. Moreover, among the 32 colistin-susceptible isolates evaluated by Gwozdzinski, the majority were Acinetobacter spp. and E. coli strains not obtained from human clinical specimens (13).

In contrast, our diverse collection of 113 resistant isolates from multiple U.S. medical centers included only 7 that were positive for mcr-1, which reflects the overall low prevalence of mcr-1 in the United States. Importantly, the susceptible isolates of Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were obtained from clinical specimens. As such, our isolates more accurately reflect those submitted for clinical testing for susceptibility to polymyxins. Consequently, the performance data presented here raise significant concerns about the applicability of CE methods to colistin susceptibility testing in clinical laboratories.

An unexpected finding of this study was high CA for Enterobacterales isolates with the standard Etest (97.6%), with only 1 VME that was not in EA. Gradient diffusion is generally regarded as an inaccurate method for colistin susceptibility testing. However, historical data have been highly variable, ranging from excellent agreement for Enterobacterales (16–18) to either moderate (9, 19–21) or high (2, 8, 11, 12, 22, 23) rates of errors, particularly VMEs. This variability is likely attributable to multiple factors, in particular the diversity of isolates evaluated in each study, as represented by MIC distributions, species and strain types, and mechanisms of resistance, including heteroresistance. While clinical strains from multiple medical centers were evaluated in our study, relatively few Enterobacterales isolates with MICs near the CLSI breakpoint were included (n = 8 with a reference MIC of 4 μg/ml and n = 0 with a reference MIC of 2 μg/ml), making an accurate estimation of categorical error rates more challenging (24). We also only included 5 isolates from the Enterobacter cloacae complex, which can frequently be heteroresistant to polymyxins. These limitations and prior literature suggest that Etest is not suitable for clinical use despite the good performance noted in our study. Further studies of the resistance mechanisms associated with VMEs by Etest may nevertheless be useful to elucidate the underlying reasons for these errors.

Other limitations of this study include the fact that only a single brand of MHB for the CE-BMD and a single brand of gradient strips for the CE-Etest were evaluated, the latter of which was a different brand from those used by Gwozdzinski et al. (13).

In summary, we found that clinical isolates tested for colistin susceptibility with CE media demonstrated low overall agreement (CA and EA) with rBMD results. Although the CE-Etest and CE-BMD did allow for more appropriate categorization of mcr-1-positive resistant isolates, these findings were not broadly applicable to organisms with other mechanisms of colistin resistance or to colistin-susceptible isolates. These methods therefore do not seem suitable for testing in clinical laboratories. Fortunately, two novel colistin susceptibility methods (colistin broth disk elution [CBDE] and colistin agar test [CAT]) were recently provisionally approved by CLSI, providing clinical laboratories with alternative methods that can be performed in-house rather than sending isolates to reference laboratories for rBMD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Andre Hsuing and the staff at Hardy Diagnostics for preparing the CE-MHA and cation-adjusted MHA, as well as Leland Vought at Accelerate Diagnostics for preparing the rBMD and CE-BMD panels.

R.M.H. is an employee and shareholder of Accelerate Diagnostics.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biswas S, Brunel JM, Dubus JC, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Rolain JM. 2012. Colistin: an update on the antibiotic of the 21st century. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10:917–934. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rojas LJ, Salim M, Cober E, Richter SS, Perez F, Salata RA, Kalayjian RC, Watkins RR, Marshall S, Rudin SD, Domitrovic TN, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Doi Y, Kaye KS, Evans S, Fowler VG, Bonomo RA, van Duin D, Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. 2017. Colistin resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: laboratory detection and impact on mortality. Clin Infect Dis 64:711–718. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monaco M, Giani T, Raffone M, Arena F, Garcia-Fernandez A, Pollini S, Network Euscape-Italy, Grundmann H, Pantosti A, Rossolini GM. 2014. Colistin resistance superimposed to endemic carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a rapidly evolving problem in Italy, November 2013 to April 2014. Euro Surveill 19:pii20939. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.42.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qureshi ZA, Hittle LE, O’Hara JA, Rivera JI, Syed A, Shields RK, Pasculle AW, Ernst RK, Doi Y. 2015. Colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: beyond carbapenem resistance. Clin Infect Dis 60:1295–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sader HS, Huband MD, Castanheira M, Flamm RK. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa antimicrobial susceptibility results from four years (2012 to 2015) of the International Network for Optimal Resistance Monitoring Program in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02252-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02252-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivas P, Rivard K. 2017. Polymyxin resistance in gram-negative pathogens. Curr Infect Dis Rep 19:38. doi: 10.1007/s11908-017-0596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y-Y, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi L-X, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu L-F, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu J-H, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindler JA, Humphries RM. 2013. Colistin MIC variability by method for contemporary clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol 51:1678–1684. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03385-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matuschek E, Ahman J, Webster C, Kahlmeter G. 2018. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of colistin: evaluation of seven commercial MIC products against standard broth microdilution for Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. Clin Microbiol Infect 24:865–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EUCAST. 2016. Recommendations for MIC determination of colistin (polymyxin E): as recommended by the joint CLSI-EUCAST Polymyxin Breakpoints Working Group. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/General_documents/Recommendations_for_MIC_determination_of_colistin_March_2016.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2019.

- 11.Kulengowski B, Ribes JA, Burgess DS. 2019. Polymyxin B Etest® compared with gold-standard broth microdilution in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae exhibiting a wide range of polymyxin B MICs. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutgring JD, Kim A, Campbell D, Karlsson M, Brown AC, Burd EM. 2019. Evaluation of the MicroScan colistin well and gradient diffusion strips for colistin susceptibility testing in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 57:e01866-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01866-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwozdzinski K, Azarderakhsh S, Imirzalioglu C, Falgenhauer L, Chakraborty T. 2018. An improved medium for colistin susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01950-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01950-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphries RM, Green DA, Schuetz AN, Bergman Y, Lewis S, Yee R, Stump S, Lopez M, Macesic N, Uhlemann A-C, Kohner P, Cole N, Simner PJ. 11 September 2019. Multi-center evaluation of colistin broth disk elution and colistin agar test: a report from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. J Clin Microbiol doi: 10.1128/JCM.01269-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CLSI. 2019. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 11th ed. M07-A11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 16.Maalej SM, Meziou MR, Rhimi FM, Hammami A. 2011. Comparison of disc diffusion, Etest and agar dilution for susceptibility testing of colistin against Enterobacteriaceae. Lett Appl Microbiol 53:546–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein FW, Ly A, Kitzis MD. 2007. Comparison of Etest with agar dilution for testing the susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other multidrug-resistant bacteria to colistin. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:1039–1040. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malli E, Florou Z, Tsilipounidaki K, Voulgaridi I, Stefos A, Xitsas S, Papagiannitsis CC, Petinaki E. 2018. Evaluation of rapid polymyxin NP test to detect colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in a tertiary Greek hospital. J Microbiol Methods 153:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chew KL, La MV, Lin RTP, Teo J. 2017. Colistin and polymyxin B susceptibility testing for carbapenem-resistant and mcr-positive Enterobacteriaceae: comparison of Sensititre, MicroScan, Vitek 2, and Etest with broth microdilution. J Clin Microbiol 55:2609–2616. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00268-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan TY, Ng SY. 2007. Comparison of Etest, Vitek and agar dilution for susceptibility testing of colistin. Clin Microbiol Infect 13:541–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfennigwerth N, Kaminski A, Korte-Berwanger M, Pfeifer Y, Simon M, Werner G, Jantsch J, Marlinghaus L, Gatermann SG. 2019. Evaluation of six commercial products for colistin susceptibility testing in Enterobacterales. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behera B, Mathur P, Das A, Kapil A, Gupta B, Bhoi S, Farooque K, Sharma V, Misra MC. 2010. Evaluation of susceptibility testing methods for polymyxin. Int J Infect Dis 14:e596–e601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dafopoulou K, Zarkotou O, Dimitroulia E, Hadjichristodoulou C, Gennimata V, Pournaras S, Tsakris A. 2015. Comparative evaluation of colistin susceptibility testing methods among carbapenem-nonsusceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4625–4630. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00868-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasoo S. 2017. Susceptibility testing for the polymyxins: two steps back, three steps forward? J Clin Microbiol 55:2573–2582. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00888-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.