The Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B (Clarity) assay is an automated, ultrasensitive immunoassay for the detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins in stool. In this study, the performance of the Clarity assay was compared to that of a multistep algorithm using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for detection of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and toxins A and B arbitrated by a semiquantitative cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA).

KEYWORDS: C. difficile, C. difficile EIA, C. difficile PCR, CDI, single-molecule counting, cytotoxin, toxin, ultrasensitive

ABSTRACT

The Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B (Clarity) assay is an automated, ultrasensitive immunoassay for the detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins in stool. In this study, the performance of the Clarity assay was compared to that of a multistep algorithm using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for detection of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and toxins A and B arbitrated by a semiquantitative cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA). The performance of the assay was evaluated using 211 residual deidentified stool samples tested with a GDH-and-toxin EIA (C. Diff Quik Chek Complete; Techlab), with GDH-and-toxin discordant samples tested with CCNA. The stool samples were stored at –80°C before being tested with the Clarity assay. For samples discordant between Clarity and the standard-of-care algorithm, the samples were tested with PCR (Xpert C. difficile; Cepheid), and chart review was performed. The testing algorithm resulted in 34 GDH+/toxin+, 53 GDH−/toxin−, and 124 GDH+/toxin− samples, of which 39 were CCNA+ and 85 were CCNA−. Clarity had 96.2% negative agreement with GDH−/toxin− samples, 100% positive agreement with GDH+/toxin+ samples, and 95.3% agreement with GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− samples. The Clarity result was invalid for one sample. Clarity agreed with 61.5% of GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ samples, 90.0% of GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ (high-positive) samples, and 31.6% of GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ (low-positive) samples. The Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay demonstrated high agreement with a testing algorithm utilizing a GDH-and-toxin EIA and CCNA. This novel automated assay may offer an accurate, stand-alone solution for C. difficile infection (CDI) diagnostics, and further prospective clinical studies are merited.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) is an anaerobic, Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium first identified in 1935 (1, 2). In the 1970s, the causative relationship between C. difficile infection (CDI) and antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis was established, and CDI is now the most common cause of nosocomial diarrhea (3–6).

CDI is a clinical diagnosis, requiring the presence of symptoms, usually acute diarrhea, and identification of either C. difficile toxins A and/or B or toxigenic species in stool. In vitro diagnostic tests for CDI have either poor clinical specificity (nucleic acid amplification tests [NAATs]), poor sensitivity (toxin enzyme immunoassays [EIAs]), or long turnaround time (cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay [CCNA] and toxigenic culture [TC]) (7, 8). Consequently, current guidelines recommend multistep testing algorithms for CDI diagnosis (9, 10).

The Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay (Clarity) is an automated and ultrasensitive assay, powered by single-molecule counting technology, for the detection of C. difficile toxins A and B in stool. In this study, the performance of the Clarity assay was compared to that of a standard-of-care algorithm using an EIA for detection of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and toxins A and B arbitrated by CCNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay.

The Clarity assay detects C. difficile toxins A and B in stool on the Singulex Clarity system, as has been described previously (11–14). Briefly, either 100 μl of a liquid or semisolid or 0.1 g (not tested in this study) of a solid stool sample is mixed (1:20) with diluent buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min. Three hundred microliters of the resulting supernatant is loaded onto the Singulex Clarity system. The sample is mixed with paramagnetic microparticles precoated with antitoxin A and antitoxin B monoclonal antibodies (capture reagent) and fluorescently labeled toxin-specific antibodies (detection reagent) and incubated at 37°C for 5 min in a reaction vessel. After incubation, unbound material is washed away, and an elution buffer is added to dissociate the immune complexes from the paramagnetic microparticles. The resulting mixture is exposed to a magnetic field to separate the paramagnetic microparticles from the dissociated fluorescently labeled antibodies, and the resulting eluate is transferred to a detection vessel where the dye-labeled molecules are detected. A proprietary algorithm counts detected events and compares these to a previously established standard curve. The Singulex Clarity software interpolates the data into a combined toxin A-toxin B concentration. The limits of detection for toxins A and B are 0.8 and 0.3 pg/ml in buffer and 2.0 and 0.7 pg/ml in stool, respectively (11). The cutoff for the Clarity assay compared to CCNA, as stated in the manufacturer’s instructions for use, is set at 12.0 pg/ml (13). Time to first result is 32 min.

Study design.

Stool samples (n = 211) from patients with suspected CDI were tested and collected at Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH) in New Haven, CT, from July to November 2018. One hundred sixteen (55.0%) of the patients were women, and 204 (96.7%) were age 18 years or older. In total, there were 194 unique patients included in the study; 13 patients had two samples and 2 patients had three samples entered. Samples were tested onsite within 2 to 12 h of collection with a rapid EIA for the detection of GDH and toxins A and B (C. Diff Quik Chek Complete [QCC], TechLab, Inc., Blacksburg, VA), and GDH-and-toxin discordant samples were tested with a semiquantitative CCNA using the C. difficile toxin/antitoxin kit reagents (catalog no. T5000; TechLab, Inc.). CCNA was performed by testing serial dilutions (1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000) of fecal filtrate of a 1:1 dilution of stool to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) suspension, in 96-well plates of laboratory-prepared human foreskin fibroblast culture (Quidel, San Diego, CA).

Residual deidentified stool samples were stored at –80°C and shipped to Singulex (Alameda, CA) for testing with the Clarity assay. The performance of Clarity was compared to that of the standard-of-care algorithm. For samples discordant between Clarity and the standard-of-care algorithm, chart review was performed and the samples were tested with NAAT (Xpert C. difficile; Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) tested at YNHH, and with a second qualitative CCNA (C. difficile TOX-B test; catalog no. T5003, TechLab; tested at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT), which utilizes a 1:10-diluted fecal filtrate in PBS, tested at a single final dilution of 1:50.

RESULTS

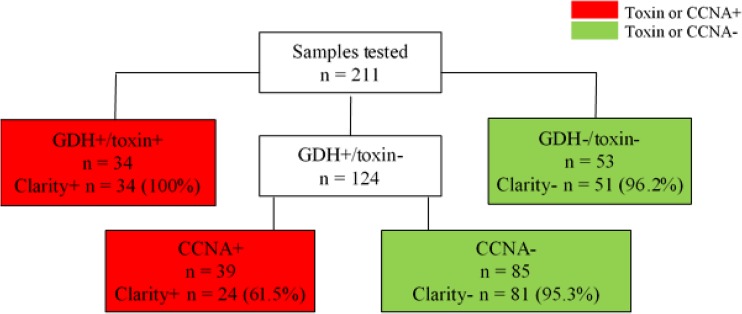

Of 211 samples tested, the standard-of-care testing algorithm (YNHH) resulted in 34 QCC GDH+/toxin+ and 53 QCC GDH−/toxin− samples (Fig. 1). Among the 124 GDH+/toxin− samples that reflexed to CCNA testing, 39 were CCNA+ and 85 were CCNA−, using the semiquantitative CCNA. Of the 73 total samples toxin+ by the standard-of-care algorithm, QCC detected 34 (46.6%), while Clarity detected all 34 QCC toxin+ and 24 of 39 CCNA+ samples, or a total of 58 of 73 toxin+ samples (79.5%). One GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− sample had invalid Clarity and NAAT results and was excluded from analysis. Thus, Clarity had 100% positive agreement with GDH+/toxin+ samples, 96.2% negative agreement with GDH−/toxin− samples, and 95.7% negative agreement with the standard-of-care algorithm. In addition, Clarity agreed with 95.3% of GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− samples.

FIG 1.

The standard-of-care testing algorithm (YNHH) and Clarity results. One GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− sample had invalid Clarity and NAAT results and was excluded from analysis. Abbreviations: GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; CCNA, cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay.

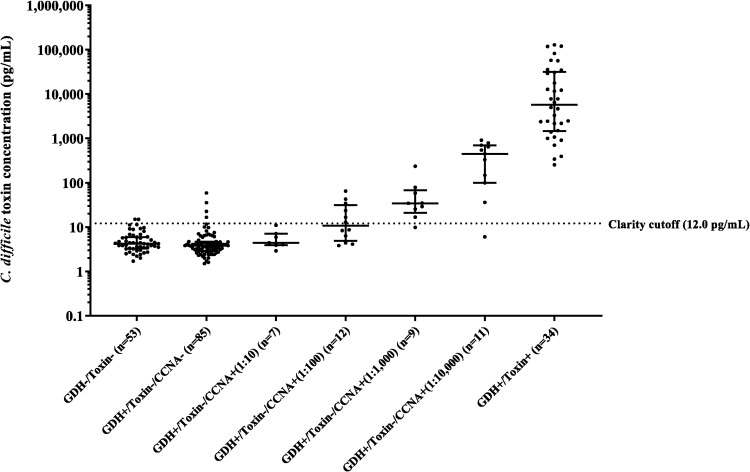

Results were further analyzed by correlating Clarity values with semiquantitative CCNA results (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Clarity agreed with 18/20 (90.0%) of high-positive GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ samples (dilution steps 1:1,000 to 1:10,000) and 6/19 (31.6%) of low-positive GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ samples (dilution steps 1:10 to 1:100) samples. Clarity was also positive in three GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− samples and two GDH−/toxin− samples.

TABLE 1.

Correlation of semiquantitative CCNA (YNHH) titers and Singulex Clarity resultsa

| CCNA dilution factor | Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| 10 | 0 | 7 | 7b |

| 100 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 1,000 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 10,000 | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Total | 24 | 15 | 39 |

Cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA) at YNHH was performed by testing serial dilutions (1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000) of a 50% stool–PBS filtrate.

Only 3 of 7 were positive by qualitative CCNA at ARUP.

FIG 2.

C. difficile toxin concentration in samples in various result categories. Combined toxin A and B concentrations are shown for stool samples with different results by GDH-and-toxin EIA and a semiquantitative CCNA (dilution steps, 1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000). The dotted line represents the cutoff for the Clarity assay (12.0 pg/ml).

Analysis of discrepant samples.

Twenty-one discrepant samples were tested by NAAT and by qualitative CCNA (Tables 2 and 3). All 15 GDH+/toxin−/CCNA+ samples that were negative by Clarity were positive by NAAT for the toxin B gene. However, only 11 of the 15 were positive for toxin by qualitative CCNA at ARUP. In particular, 3 of 7 CCNA+ at the 1:10 dilution at YNHH tested CCNA− at a 1:50 final dilution at ARUP.

TABLE 2.

Comparison between the Clarity toxin assay and the standard-of-care algorithm utilizing a GDH-and-toxin EIA and a semiquantitative CCNAa

| No. with indicated result | Standard-of-care algorithm (YNHH) |

Singulex Clarity | Arbitration of discrepant results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QCC GDH | QCC toxin | Reflex to CCNA | Toxin B gene NAAT | CCNA ARUP | ||

| Toxin positive by algorithm (n = 73) | ||||||

| 34 | Pos | Pos | ND | Pos | ND | ND |

| 24 | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | ND | ND |

| 15b | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | 11/15 pos |

| Toxin negative by algorithm (n = 137) | ||||||

| 81c | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | ND | ND |

| 2d | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | 1/ 2 Pos |

| 1 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg |

| 51 | Neg | Neg | ND | Neg | ND | ND |

| 2 | Neg | Neg | ND | Pos | Neg | Neg |

QCC, C. Diff Quick Chek Complete; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; Pos, positive; Neg, negative; ND, not done.

Only 11 of 15 were positive by qualitative CCNA at ARUP.

One sample invalid by both Clarity and NAAT was excluded.

Both were NAAT positive; one of two was positive by CCNA at ARUP. The other patient became QCC toxin positive 8 days later.

TABLE 3.

C. difficile discrepant test result chart reviewa

| Result and study IDb | Age | Host | Significant diarrhea | History of CDI | Laxative | CDI Rx | Response to Rx | Follow-up | CCNA YNHH | PCR CT value | CCNA ARUP | Clarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCNA+/PCR+/Clarity− | ||||||||||||

| CD2-189 | 75 | ESRD, abdominal pain, diarrhea | Large stool in rectum; given mineral oil to pass stool | Y | Y | Y | No further diarrhea | Negative tests | 10 | 29.6 | Neg | 10.9 |

| CD2-104 | 88 | Dementia, stroke, PNA | Liquid stool | N | N | Y | No response | Transfer to comfort care; deceased | 10 | 30.8 | Neg | 3.9 |

| CD-44 | 87 | Lives in ECF. Melena, reported diarrhea, given loperamide (Imodium) | No diarrhea in hospital; formed stool tested | Y | N | Y | No diarrhea in hospital | Doing well | 10 | 33 | Neg | 7.1 |

| CD2-209 | 74 | Fell at home, COPD, CKD, GI bleed, history of CDI | GI bleed | Y | N | Y | GI bleed resolved | WBC remained elevated for wks | 10 | 34.7 | Neg | 4 |

| CD2-190 | 81 | Stroke, PNA | Liquid stool | N | N | Y | Died acutely | NA | 10 | 34.6 | Pos | 5.9 |

| CD2-48 | 87 | Metastatic CA | None. Given laxative for constipation. | N | Y | N | Not treated | Transfer to Hospice; deceased | 10 | 35.1 | Pos | 2.9 |

| CD2-132 | 58 | Metastatic prostate CA, diverticulitis, ETOH withdrawal, suicide attempt | Intermittent loose stools. Prior result [CD2-09] noted and treated | N | N | Y | Not stated | No further tests | 10 | 28.5 | Pos | 4.4 |

| CD2-09 | 58 | Metastatic prostate CA, diverticulitis, ETOH withdrawal | Intermittent. Asymptomatic at discharge. Cytotoxin result not seen. | N | N | N | Not treated | Readmitted. See CD2-132. | 100 | 30 | Pos | 6.3 |

| CD2-07 | 64 | Fall, aspiration PNA | Liquid stool | N | N | Y | Died acutely respiratory failure | Deceased | 100 | 21.2 | Pos | 8.3 |

| CD2-211 | 44 | ESRD, BKA stump infection | Chronic diarrhea, no clear etiology despite prior colonoscopy. Discharged before finishing treatment. | Y | N | Y | Readmitted 2 mo later, again reported chronic diarrhea, C. difficile tests negative | Subsequent C. difficile tests negative | 100 | 25.3 | Pos | 8.6 |

| CD2-165 | 78 | Surgery, pituitary adenoma, intracranial bleed, PNA | Loose stools, incontinent. On tube feeds. | N | Y | Y | Some diarrhea continued, but C. difficile test negative | Subsequent C. difficile tests negative | 100 | 25.7 | Pos | 4.1 |

| CD2-78 | 80 | Metastatic prostate CA, ESRD, dialysis, UTI, WBC increased to 37,000 on antibiotics | Details not recorded | Y | Y | Y | Notes state diarrhea improved, WBC fell | Repeat C. difficile test while on therapy positive | 100 | 29.5 | Pos | 4.4 |

| CD2-22 | 71 | Respiratory failure | Watery stools x 2 d | N | N | Y | Died acutely from respiratory failure | Deceased | 100 | 32.9 | Pos | 3.8 |

| CD2-108 | 89 | Admission diagnosis: sepsis due to CDI | Liquid stools | N | N | Y | Resolved | None | 1,000 | 31.6 | Pos | 9.8 |

| CD2-80 | 88 | Lives in ECF. ESRD, PNA, diarrhea | Diarrhea, abdominal pain | Y | N | Y | Resolved | None | 10,000 | 27.8 | Pos | 6 |

| CCNA−/PCR+/Clarity+ | ||||||||||||

| CD2-171 | 77 | Cirrhosis. On antibiotics for PNA. | Slightly worse than baseline | Y | N | N | Not treated | Discharged without therapy. No further C. difficile tests. | Neg | 22.6 | Pos | 35.2 |

| CD2-179 | 74 | Cervical CA, BO, ileostomy | Ostomy output increased, slight blood | Y | Y | N | Not treated | Rapid toxin positive 8 days later, treated | Neg | 28.5 | Neg | 22.4 |

| CCNA−/PCR−/Clarity+ | ||||||||||||

| CD2-30 | 55 | MI, MVR, VAP | Not stated | N | Y | N | Not treated | No diarrhea or further testing | ND (GDH neg) | Neg | Neg | 14.8 |

| CD2-81 | 51 | Lymphoma, transplant | No. Copious formed stool in bowel. | N | N | N | Not treated | C. difficile tests negative | ND (GDH Neg) | Neg | Neg | 14.9 |

| CD2-17 | 64 | Outpatient. Esophageal reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, IBS | Reported diarrhea for 2 wks | N | N | Y | Treated inappropriately based on GDH+ only | No other diarrhea or C. difficile testing | Neg | Neg | Neg | 16.6 |

Abbreviations: ID, identifier; CDI, C. difficile infection; Rx, treatment; YNHH, Yale New Haven Hospital; CT, cycle threshold; ARUP, ARUP reference laboratory; Y, yes; N, no; NA, not applicable; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; CA, cancer; PNA, pneumonia; ECF, extended-care facility; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ETOH, ethanol; BKA, below-knee amputation; UTI, urinary tract infection; BO, bowel obstruction; MI, myocardial infarction; MVR, mitral valve replacement; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; WBC, white blood cell.

CCNA performed at YNHH.

Chart reviews revealed the difficulty in making a clinical diagnosis of CDI as the cause of a patient’s symptoms. Selected data from chart reviews are presented in Table 3. For 15 CCNA+/Clarity− discrepant samples, 14 patients had prior hospital admissions and multiple comorbidities. Two patients with the highest CCNA titers, 1:1,000 and 1:10,000, appeared to have CDI and responded to therapy. Of note, their NAAT cycle threshold (CT) values were higher than the cutoff of 27, which has been reported to correlate with the presence of free toxins (15–17). Of the other 12 patients with CCNA-positive results of 1:10 or 1:100, 3 had no diarrhea in the hospital. Indeed, two of these were constipated and had been given laxatives and one had a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed that could also account for loose stools. Two had chronic diarrhea, one was on tube feedings, and both had minimal or no response to treatment. Two were on laxatives, two were not treated, three died acutely of other causes, and two patients were transferred to hospice care.

Two GDH+/toxin−/CCNA− samples positive by Clarity were NAAT+. One of these was also CCNA+ at ARUP, had a CT of 22.6, and had a Clarity result of 35.2 pg/ml (cutoff, 12.0 pg/ml), yet the patient was not treated and recovered. The other patient with a NAAT+ (CT, 28.5) and Clarity+ (22.4) stool, but negative by CCNA at both YNHH and ARUP, had a GDH+/toxin+ sample 8 days later and was then treated for CDI. In addition, three Clarity+ samples were negative by both NAAT and qualitative CCNA.

DISCUSSION

Making a timely and accurate laboratory diagnosis of CDI remains a challenge. Toxigenic culture and NAATs target the C. difficile toxin gene and detect toxigenic bacteria and cannot differentiate a carrier state from active disease (18–20). CCNA, a gold standard method since its introduction in 1978 (3), has been shown in recent reports to correlate with mortality, in contrast to NAAT (18), but requires cell culture expertise, use of sensitive cell monolayers, and 24 to 48 h of incubation; thus, it is rarely used for routine diagnosis. The most common method to detect free toxin in stool, toxin EIA, has suboptimal sensitivity (7). Thus, more sensitive, rapid, and user-friendly toxin assays are urgently needed.

In this study, the Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay was found to be significantly more sensitive than the QCC toxin EIA, detecting all samples (n = 34) positive by QCC and 61.5% (24 of 39) of the samples positive only by the semiquantitative CCNA. In addition, Clarity detected two additional likely true positives missed by CCNA at YNHH. Clarity toxin concentration had a strong linear correlation with semiquantitative CCNA titers.

The semiquantitative CCNA used in this study was shown to be more sensitive than the qualitative CCNA available at commercial reference laboratories and used in a previous study (11). Of the 15 semiquantitative CCNA+/Clarity− samples, 13 were low positives and for many patients, the diagnosis of CDI could be questioned due to presence of other possible causes of diarrhea, absence of diarrhea, failure to respond to treatment, and/or chronic diarrhea with subsequent negative CDI test results. Although all CCNA+ samples were also NAAT+, and thus toxigenic bacteria were present, it has been shown that free toxin can also be found in patients without CDI (21), and a low-positive CCNA might therefore not indicate that C. difficile is the cause of the patient’s symptoms. While it is possible that the Clarity result may actually correlate better with CDI, further prospective clinical studies are needed to answer this question.

In this study, there were also 3 samples positive by Clarity and negative by both NAAT and qualitative CCNA. However, the NAAT assay detects the presence of the toxin B gene and CCNA primarily detects the presence and activity of toxin B (7), while the Clarity assay detects both toxins A and B. However, these Clarity+ samples were not tested for toxin A, and two were GDH negative and thus negative for C. difficile bacteria. Thus, although not applicable in these cases, it should be noted that some Clarity-positive samples could potentially be explained by detection of toxin A. The role of the different toxins in CDI has been debated (22), and recent studies have shown that strains predominantly producing toxin A are relevant in CDI and can cause disease (23–25). Unfortunately, determination of the prevalence of toxin A, toxin B, and toxins A and B among the samples tested was beyond the scope of the study.

This study highlights the challenges in accurately diagnosing CDI in symptomatic patients. CDI is a toxin-mediated disease; due to the high incidence of both diarrhea and colonization in tested populations, the detection of toxigenic organisms leads to overdiagnosis and overtreatment (7, 18, 19). In a recent study, it was shown that presence of toxins, as measured with the Clarity assay, correlated with CDI relapse, death, and severity of disease and that the proportion of CDI overdiagnosis was more than three times higher in NAAT+/toxin− than in NAAT+/toxin+ patients (14). Use of the Clarity ultrasensitive toxin assay improved clinical specificity compared with that of NAAT, without the poor sensitivity shown by contemporary toxin EIAs (14).

In summary, the Singulex Clarity C. diff toxins A/B assay demonstrated high agreement with a testing algorithm utilizing a GDH-and-toxin EIA and a semiquantitative CCNA, and there was a strong linear correlation between Clarity toxin concentration and semiquantitative CCNA results.

While the novel, automated Clarity toxin assay may offer an accurate, stand-alone solution for CDI diagnostics, at the time of publication of this article, Singulex has chosen not to pursue commercial application of the Clarity assay. Nevertheless, our results shed further light onto the potential of single-molecule counting technology for free-toxin detection, which should continue to inform C. difficile diagnostics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The contributions of Sandra Cohen, Greta Edelman, and the Clinical Virology Laboratory staff at Yale New Haven Hospital are greatly appreciated.

J.E., P.K., N.N., and J.S. were employees of Singulex, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall I, O’Toole E. 1935. Intestinal flora in newborn infants, with description of a new pathogenic anaerobe Bacillus difficilis. Am J Dis Child 49:390–402. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1935.01970020105010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawson PA, Citron DM, Tyrrell KL, Finegold SM. 2016. Reclassification of Clostridium difficile as Clostridioides difficile (Hall and O’Toole 1935) Prévot 1938. Anaerobe 40:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. 1978. Role of Clostridium difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology 75:778–782. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(78)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, Farley MM, Holzbauer SM, Meek JI, Phipps EC, Wilson LE, Winston LG, Cohen JA, Limbago BM, Fridkin SK, Gerding DN, McDonald LC. 2015. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 372:825–834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies KA, Ashwin H, Longshaw CM, Burns DA, Davis GL, Wilcox MH, EUCLID study group. 2016. Diversity of Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes in Europe: results from the European, multicentre, prospective, biannual, point-prevalence study of Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalised patients with diarrhoea (EUCLID), 2012 and 2013. Euro Surveill 21:30294. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.29.30294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voth DE, Ballard JD. 2005. Clostridium difficile toxins: mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnham C-A, Carroll KC. 2013. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: an ongoing conundrum for clinicians and for clinical laboratories. Clin Microbiol Rev 26:604–630. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock NR. 2016. Ultrasensitive detection and quantification of toxins for optimized diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol 54:259–264. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02419-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, Dubberke ER, Garey KW, Gould CV, Kelly C, Loo V, Shaklee Sammons J, Sandora TJ, Wilcox MH. 2018. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 66:e1–e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crobach MJT, Planche T, Eckert C, Barbut F, Terveer EM, Dekkers OM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ. 2016. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the diagnostic guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 22(Suppl 4):S63–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandlund J, Bartolome A, Almazan A, Tam S, Biscocho S, Abusali S, Bishop JJ, Nolan N, Estis J, Todd J, Young S, Senchyna F, Banaei N. 2018. Ultrasensitive detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins A and B by use of automated single-molecule counting technology. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00908-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00908-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandlund J, Mills R, Griego-Fullbright C, Wagner A, Estis J, Bartolome A, Almazan A, Tam S, Biscocho S, Abusali S, Nolan N, Bishop JJ, Todd J, Young S. 2019. Laboratory comparison between cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay and ultrasensitive single molecule counting technology for detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins A and B, PCR, enzyme immunoassays, and multistep algorithms. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 95:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen G, Young S, Wu AHB, Herding E, Nordberg V, Mills R, Griego-Fullbright C, Wagner A, Ong CM, Lewis S, Yoon J, Estis J, Sandlund J, Friedland E, Carroll KC. 2019. Ultrasensitive detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins in stool using single molecule counting technology: comparison with CCCNA free toxin detection. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00719-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00719-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandlund J, Estis J, Katzenbach P, Nolan N, Hinson K, Herres J, Pero T, Peterson G, Schumaker J-M, Stevig C, Warren R, West T, Chow S-K. 2019. Increased clinical specificity with ultrasensitive detection of Clostridioides difficile toxins: reduction of overdiagnosis compared to nucleic acid amplification tests. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00945-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00945-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senchyna F, Gaur RL, Gombar S, Truong CY, Schroeder LF, Banaei N. 2017. Clostridium difficile PCR cycle threshold predicts free toxin. J Clin Microbiol 55:2651–2660. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00563-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandlund J, Wilcox MH. 2019. Ultrasensitive detection of Clostridium difficile toxins reveals suboptimal accuracy of toxin gene cycle thresholds for toxin predictions. J Clin Microbiol 57:e01885-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01885-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies K, Wilcox M, Planche T. 2018. The predictive value of quantitative nucleic acid amplification detection of Clostridium difficile toxin gene for faecal sample toxin status and patient outcome. PLoS One 13:e0205941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Planche TD, Davies KA, Coen PG, Finney JM, Monahan IM, Morris KA, O’Connor L, Oakley SJ, Pope CF, Wren MW, Shetty NP, Crook DW, Wilcox MH. 2013. Differences in outcome according to Clostridium difficile testing method: a prospective multicentre diagnostic validation study of C difficile infection. Lancet Infect Dis 13:936–945. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, Leslie JL, Chin DL, Wang S, Nguyen HH, Huang B, Tang Y-W, Lee LW, Kim K, Taylor S, Romano PS, Panacek EA, Goodell PB, Solnick JV, Cohen SH. 2015. Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med 175:1792–1801. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kvach EJ, Ferguson D, Riska PF, Landry ML. 2010. Comparison of BD GeneOhm Cdiff real-time PCR assay with a two-step algorithm and a toxin A/B enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of toxigenic Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol 48:109–114. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01630-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollock NR, Banz A, Chen X, Williams D, Xu H, Cuddemi CA, Cui AX, Perrotta M, Alhassan E, Riou B, Lantz A, Miller MA, Kelly CP. 2019. Comparison of Clostridioides difficile stool toxin concentrations in adults with symptomatic infection and asymptomatic carriage using an ultrasensitive quantitative immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis 68:78–86. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyerly DM, Krivan HC, Wilkins TD. 1988. Clostridium difficile: its disease and toxins. Clin Microbiol Rev 1:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzenbach P, Dave G, Murkherjee A, Todd J, Bishop J, Estis J. 2018. Single molecule counting technology for ultrasensitive quantification of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. IDWeek 2018, San Francisco, CA.

- 24.Banz A, Lantz A, Riou B, Foussadier A, Miller M, Davies K, Wilcox M. 2018. Sensitivity of single-molecule array assays to detect Clostridium difficile toxins in comparison to conventional laboratory testing algorithms. J Clin Microbiol 65:e00452-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00452-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Q, Pollock NR, Banz A, Lantz A, Xu H, Gu L, Gerding DN, Garey KW, Gonzales-Luna AJ, Zhao M, Song L, Duffy DC, Kelly CP, Chen X. 11 August 2019. Toxin A-predominant pathogenic C. difficile: a novel clinical phenotype. Clin Infect Dis. pii:ciz727. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]