Abstract

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is caused by silencing of the FMR1 gene and consequent absence of its protein product, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). FMRP is an RNA-binding protein that can suppress translation. The absence of FMRP leads to symptoms of FXS including intellectual disability and has been proposed to lead to abnormalities in synaptic plasticity. Synaptic plasticity, protein synthesis and cellular growth pathways have been studied extensively in hippocampal slices from a mouse model of FXS (Fmr1 KO). Enhanced metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5)-dependent long-term depression (LTD), increased rates of protein synthesis, and effects on signaling molecules have been reported. These phenotypes were found under amino acid starvation, a condition that has widespread, powerful effects on activation and translation of proteins involved in regulating protein synthesis. We asked if this nonphysiological condition could have effects on Fmr1 KO phenotypes reported in hippocampal slices. We performed hippocampal slice experiments in the presence and absence of amino acids. We measured rates of incorporation of a radiolabeled amino acid into protein to determine protein synthesis rates. By means of Western blots, we assessed relative levels of total and phosphorylated forms of proteins involved in signaling pathways regulating translation. We measured evoked field potentials in area CA1 to assess the strength of the long-term depression response to mGluR activation. In the absence of amino acids, we replicate many of the reported findings in Fmr1 KO hippocampal slices, but in the more physiological condition of inclusion of amino acids in the medium, we did not find evidence of enhanced mGluR5-dependent LTD. Activation of mGluR5 increased protein synthesis in both wild type and Fmr1 KO. Moreover, mGluR5-activation increased eIF2α phosphorylation and decreased phosphorylation of p70S6k in slices from Fmr1 KO. We propose that the eIF2α response is a cellular attempt to compensate for the lack of regulation of translation by FMRP. Our findings call for a re-examination of the mGluR theory of FXS.

Keywords: fragile X syndrome, hippocampal slice, long term depression, eIF2α, translation rate, protein synthesis

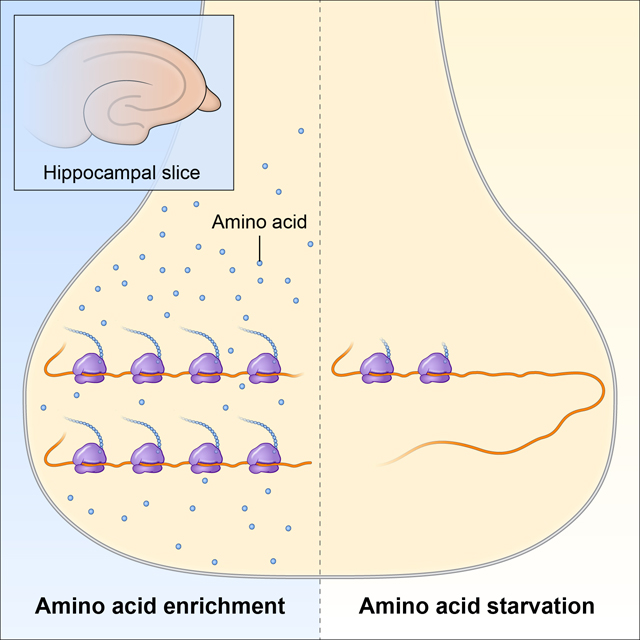

Graphical Abstract

Previous studies of protein synthesis, long-term depression (LTD), and signaling pathways in hippocampal slice preparations indicate effects of the absence of FMRP in Fmr1 KO mice. One of the conditions of these studies was amino acid starvation, a condition that has powerful effects on activation and translation of proteins involved in regulating protein synthesis. Our studies demonstrate that in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice incubated in amino acid-enriched medium, LTD and translation rates are similar to control mice, but following mGluR5 activation, eIF2a phosphorylation is increased and P70S6 kinase phosphorylation is decreased compared to control mice. Results suggest tissue attempts to compensate for the absence of regulation of translation by FMRP.

Graphical Abstract by Alan Hoofring, NIH Medical Arts Design Section

Introduction

In fragile X syndrome (FXS), FMR1, the gene coding for fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), is silenced due to an expanded CGG repeat sequence in the 5’untranslated region of the gene. The absence of FMRP results in a constellation of symptoms including intellectual disability, sensory hypersensitivity, hyperactivity, autistic-like behavior and susceptibility to seizures. FMRP contains RNA-binding motifs including two K homology (KH) domains and an arginine/glycine-rich RNA-binding region (RGG box) and associates with actively translating ribosomes (Ashley et al. 1993; Feng et al. 1997; Siomi et al. 1993). In vitro evidence supports a role for FMRP as a suppressor of translation (Laggerbauer et al. 2001; Li et al. 2001).

Our in vivo studies of regional rates of cerebral protein synthesis (rCPS) in adult Fmr1 knockout (KO) and wild type (WT) mice indicated elevated hippocampal rCPS in Fmr1 KO mice (Qin et al. 2005). In accord with these findings, experiments in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice showed increased translation rates over WT (Dölen et al. 2007; Osterweil et al. 2010). Experiments in hippocampal slices designed to test the efficacy of a plasticity response demonstrated enhanced group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent long-term depression (LTD) in slices from Fmr1 KO mice (Huber et al. 2002). These findings led to the advancement of the mGluR theory of FXS (Bear et al. 2004) which proposed that many of the symptoms of FXS might be explained by excessive protein synthesis downstream of group 1 mGluR activation. Further exploration of the mGluR theory in hippocampal slice experiments found that activation of group 1 mGluRs with dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) resulted in increased rates of translation in WT but not Fmr1 KO slices and increased phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) in both WT and Fmr1 KO slices (Osterweil et al. 2010). A thorough examination of effects of mGluR activation on components of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (Akt)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTORC1) signaling pathways showed no differences in slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice (Osterweil et al. 2010). Ultimately, it was proposed that treatment of FXS with an mGluR negative allosteric modulator would rescue the excessive protein synthesis and ameliorate symptoms in this disease.

Accordingly, we have attempted to establish an in vitro assay for rates of translation in hippocampal slices to facilitate screening of compounds as potential therapeutics in this disease. In the development of our assay we made specific modifications to published methods with the intention of creating a more physiologically relevant system. Previous experiments in the hippocampal slice preparation were performed in the absence of amino acids in the medium; we denote this condition as amino acid starvation (AAS). In our preparation, we adjusted the incubation medium to include unlabeled essential amino acids at physiological concentrations; we use the term amino acid replete (AAR) to describe this condition. In addition, we used radiolabeled leucine (L-[4,5-3H]leucine) as the tracer amino acid to enable the calculation of a rate of incorporation of leucine into protein. Our results do not agree with published reports, and we present herein an explanation for the differences between our results and those published.

Our experiments indicate that the presence or absence of essential amino acids in the medium have a profound influence on translation and the differential effects of activation of group 1 mGluRs on hippocampal slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice. In the presence of amino acids, we found no difference in baseline rates of translation in hippocampal slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice. Activation of group 1 mGluRs resulted in increases in translation rates in both genotypes. Effects on signaling molecules involved in the regulation of translation indicate that, following treatment with DHPG, phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) and p70S6k were increased and decreased respectively in slices from Fmr1 KO but not WT mice. These results indicate that pathways regulating translation in response to group 1 mGluR activation are differentially affected in the absence of FMRP. We further tested for enhanced group 1 mGluR-activated LTD in Fmr1 KO mice as reported previously (Huber et al. 2002), and found no difference in LTD between slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice in AAR conditions.

Materials and Methods

Chemical, reagents and drugs

All reagents used in the current experiment were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA) unless noted otherwise. Reagents used in the preparation of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) included; sucrose (Cat. No. 84097), sodium chloride (Cat. No. 57653), potassium chloride (Cat. No. P5405), NaH2PO4 (Cat. No. 7892), NaHCO3 (Cat. No. S6014), D-(+)-glucose (Cat. No. G7021), HEPES (Cat. No. H4034), (+)-sodium L-ascorbate (Cat. No. A4034), thiourea (Cat. No. T7875), sodium pyruvate (Cat. No. P2256), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Cat. No. A7250), MEM Amino Acids Solution (50X) (Cat. No. 11130), NaOH (Cat. No. S8045). Drug treatments used in our experiments were (RS)-3,5-DHPG; (Tocris; Ellisville, MO, US) (Cat. No. 0342/1) and 2-p-methoxyphenylmethyl-3-acetoxy-4-hydroxypyrrolidine (anisomycin; Tocris) (Cat. No. 1290/10). Other reagents used include ethylenedinitrilotetraacetic acid (EDTA; 0.5 M, pH 8.0; Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) (Cat. No. 351–027), ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) (Cat. No. E3889), Triton™ X-100 Cat. No. (X100), Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) (Cat. No. 78425), trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (Cat. No. T6399), Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail, 100X(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (Cat.No. 78441), T-PER™ Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (Cat. No. 78510), and 2-mercaptoethanol (Cat. No. M6250).

Animals

Male Fmr1 KO (Jackson Labs: B6.129P2-Fmr1tm1Cgr/J Stock No. 003025) (n = 116) and WT (n = 121) mice on a C57BL/6J background were generated from heterozygous Fmr1 KO female and WT male breeder pairs in-house. Animals were weaned at 21 days of age. Genotyping was performed on tail biopsies as previously described (Qin et al. 2005). The following primers were used: 5-ATCTAGTCATGCTATGGATATCAGC-3 and 5-GTGGGCTCTATGGCTTCTGAGG-3primers were used to screen for the presence or absence of the mutant allele. Animals were group housed (2–5/cage) in a climate-controlled facility with access to food and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Care and Use of Animals and approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee (LCM-07). This study was not pre-registered. Animal assignment was not randomized as it was not relevant for the experimental goals. Additionally, animals were used as soon as available. Numbers were assigned to animals by another researcher so that those conducting the experiment were blinded to animal genotype during analysis of rates of protein synthesis, Western Blots, and LTD recordings. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Hippocampal Slice Preparation

The compositions of media in which hippocampal slices were prepared, incubated, and dissected are given in Table 1. For experiments under AAR conditions all media included a full complement of essential amino acids. Similarly, for experiments under amino acid starvation (AAS) conditions, all media lacked amino acids. Unanesthetized animals (postnatal day (P)30-P51) were euthanized by decapitation between 9 and 11:30 am, and brains were rapidly removed and placed in ice cold Sucrose aCSF for 45 s (Figure 1). The frontal cortex was removed, the remaining tissue was glued to a puck, and slices (350 μm in thickness) were prepared in ice cold Sucrose aCSF, bubbled with 95% O2 / 5% CO2, by means of a Leica VT1000 S vibratome (Leica, Deerfield, IL, USA). Hippocampal slices were used in three independent sets of experiments as described below. Each set of experiments had its own endpoint. The first set of experiments was designed to measure the rate of incorporation of leucine into protein in slices from both genotypes and under different conditions. The second set of experiments was designed to assess levels of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of signaling molecules involved in the regulation of translation. Relative levels of these proteins were assessed in both genotypes and under different conditions. The third set of experiments was designed to assess the strength of the LTD response following mGluR5 activation.

Table 1.

Composition of artificial CSF media.

| Amino Acid Replete |

Amino Acid

Starvation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose aCSF | Standard aCSF | Dissection aCSF | Sucrose aCSF | Standard aCSF | Dissection aCSF | |

| Concentration (mM) |

||||||

| Sodium chloride | - | 124 | 124 | - | 124 | 124 |

| Sucrose | 150 | - | - | 150 | - | - |

| Potassium chloride | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| NaH2PO4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| NaHCO3 | 30 | 24 | 24 | 30 | 24 | 24 |

| HEPES | 20 | 5 | - | 20 | 5 | - |

| Glucose | 25 | 12.5 | - | 25 | 12.5 | - |

| Sodium ascorbate | 5 | - | - | 5 | - | - |

| Thiourea | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Sodium pyruvate | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - |

| N-Acetyl-L-cysteine | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| Magnesium sulfate | 10 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| Calcium chloride | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| L-Arginine HCl | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | - | - | - |

| L-Cystine | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | - | - |

| L-Histidine HCl | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| L-Isoleucine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| L-Leucine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| L-Lysine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| L-Methionine | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | - | - |

| L-Phenylalanine | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| L-Threonine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| L-Tryptophan | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | - | - | - |

| L-Tyrosine | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| L-Valine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| Anisomycin | - | - | 0.01 | - | - | 0.01 |

pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH; 291–312 mOsm

Fig. 1.

Timeline of experiment. Following decapitation brains were removed and hippocampal slices prepared for experiments.

Measurement of Rates of Protein Synthesis

Five slices, containing ventral and dorsal hippocampus were transferred by means of a fine paintbrush to 100 μm Falcon™ cell strainers (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in room temperature Sucrose aCSF, bubbled with 95% O2 / 5% CO2, for 10 min. Slices were then transferred to Standard aCSF, bubbled with 95% O2 / 5% CO2, for 4 h of recovery at 37°C. Strainers containing brain slices were then transferred to new baths of 125 mL Standard aCSF for drug/condition treatment. Slices treated with DHPG were incubated in Standard aCSF with 100 μM DHPG for 5 min before transfer to Standard aCSF containing L-[4,5-3H]leucine (SA, 60–120 Ci/mmol, MORAVEK, Inc., Brea, CA) (Cat. No. MT 672), at the concentration of 4 μCi/mL, for 30 min. Following incubation in [3H]leucine, slices were transferred to ice cold Dissection aCSF, and whole hippocampi were dissected and transferred to Precellys™ soft tissue homogenizing CK14 tubes (Bertin Corporation, Rockville, MD).

Dissected hippocampi were homogenized in 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 17 mM Triton X-100, 0.01% by volume Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X), by means of a Precellys Evolution Homogeniser (Bertin Corporation) before addition of TCA to a final concentration of 10%. Precipitated protein was centrifuged and washed 5 times with 10% TCA to remove contaminating free [3H]leucine. Protein pellets were rinsed 3 times with acetone ( −40°C) and air dried for 1 hr. Pellets were resuspended in 0.1 M NaOH and shaken for 45 min at 37°C. Concentrations of [3H] and protein in each sample were determined by liquid scintillation counting and Pierce™ BCA protein assay (Thermo-Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. The specific activity of [3H]leucine in the incubation medium was determined in each experiment. In AAS experiments, we used the specific activity of the [3H]leucine from the supplier as the specific activity of leucine in the medium ( 1.55–2.27 x 105 dpm/pmol ). The rate of PS in each sample was calculated as follows:

in which PS is the rate of incorporation of leucine into protein in pmol/mg protein /min and DPM is disintegrations per minute of 3H.

Western Blot

Samples for Western blot analysis were sliced and recovered as described above. Strainers containing brain slices were then transferred to new baths of 125 mL Standard aCSF for drug/condition treatment. Slices treated with DHPG were incubated in Standard aCSF with 100 μM DHPG for 5 min. Following incubation, slices were transferred to ice cold Dissection aCSF, and whole hippocampi were dissected and immediately frozen on dry ice in pre-weighed Precellys tubes and stored in −80°C until processing. On the day of processing, hippocampal slices were thawed and homogenized two times for 30 s at 5,000 rpm in 10% (weight/volume) solution of T-Per protein extraction reagent with 1% EDTA and 1% Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail by means of Precellys soft tissue homogenizing tubes with ceramic beads (Bertin Corporation). Homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 15 min at 4°C, supernatant fractions collected, and protein concentrations measured by means of a BCA protein assay.

Protein in the supernatant (10 μg) was denatured at 95°C for 5 min with an equal volume of 2x Laemmli buffer (5% 2-mercaptoethanol) and electrophoresed on a 4–15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C in the primary antibody solution followed by 1 h at room temperature in secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked 1:10,000 (Bio-Rad Laboratories)). Antibody staining was visualized after incubation in Clarity substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a ChemiDoc MP Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (RRID: SCR 014210). For normalization of Western blots, we employed the Stain-Free technology (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Primary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) were: p-ERK1/2 (4370) (RRID:AB_2315112), ERK (4695) (RRID:AB_390779), p-eIF2α (3398) (RRID:AB_2096481), eIF2α (5324) (RRID:AB_10692650), p-mTOR (5536) (RRID: AB_10691552), mTOR (2983) (RRID: AB_2105622), p-p70 S6K (9234) (RRID: AB_2269803), p70 S6K (2708) (RRID: AB_390722), p-S6 235/236 (2211) (RRID: AB_331679), p-S6 240/244 (2215) (RRID: AB_331682), S6 (2217) (RRID: AB_331355), p-Akt (4060) (RRID: AB_2315049), Akt (9272) (RRID:AB_329827), p-GCN2 (OABF01173; Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA, US) (RRID:AB_2801396) and GCN2 (ab137543; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (RRID:AB_2801397). Antibodies were diluted 1:1000.

At the outset nine animals per group were examined, however some results were excluded because of artifacts on the blot or because values were greater than two standard deviations from the mean and considered outliers. Details of each removed value are included in the figure legends.

Electrophysiology Recordings

Brain slices (400 μm in thickness) prepared in a similar manner as described above were recovered in Standard aCSF at 32°C for 30 min before being moved to room temperature Standard aCSF for 1.5 h. Following recovery slices were transferred to an interface recording chamber where they were perfused with bubbled (95% O2 / 5% CO2) Standard aCSF at 32°C at a rate of 2 mL/min. Field-recordings were performed by placing a stimulating electrode in the CA3 region of the hippocampus to stimulate the Schaffer collateral pathway and a recording electrode in the CA1 region. Recording electrodes (1 – 2 MΩ) generated the day of recordings by a micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co, USA) were filled with Standard aCSF. Field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSP) were elicited every 15 s through a Master-8 stimulator (A.M.P.I, Israel), recorded with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier, and digitized using Digidata 1440A (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). After baseline recording, 100 uM DHPG was perfused on slices for 15 min, then slices were returned to Standard aCSF, and recording continued for 90 min. fEPSP slopes were analyzed using the Clampfit 9 software (Molecular Devices), and every four fEPSPs were averaged to generate an average slope per minute. A grand average of 30 min of baseline fEPSPs was generated and every fEPSP recorded after DHPG treatment was normalized to this mean. Only slices with fEPSP covariances less than 10% during baseline recording were used for final analysis. The number of successful recordings that met baseline criteria are as follows; 17 LTD recordings generated from 12 WT mice under AAS, 16 LTD recordings generated from 14 Fmr1 KO mice under AAS, 11 LTD recordings generated from 11 WT mice under AAR, 10 LTD recordings generated from 5 Fmr1 KO mice under AAR.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEMs. Our sample sizes were based on numbers used in published studies. We did not test for the normality of data. We did test for outliers; if points were greater than two standard deviations from the mean of all samples they were excluded. Specific explanations of exclusions are presented in the figure legends. For the statistical analysis of PS results, we analyzed the data from AAR and AAS conditions separately because the values differed by two orders of magnitude. Results of PS studies under AAR and AAS conditions were analyzed by means of 2-way ANOVA with genotype and treatment as between subjects factors. Western blot results were analyzed by means of 3-way ANOVA with amino acid condition, genotype and treatment as between subject factors. For the statistical analysis of electrophysiology results, responses were averaged over 10 min epochs for 90 mins following DHPG treatment. These results were analyzed by means of a 3-way repeated measures ANOVA with epoch as a within subjects variable and genotype and amino acid condition as between subjects variables. When appropriate, we further probed for differences by means of Bonferroni t-tests. These analyses were made by means of SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Protein synthesis response of hippocampal slices to group 1 mGluR-activation by DHPG depends on amino acids in the incubation medium

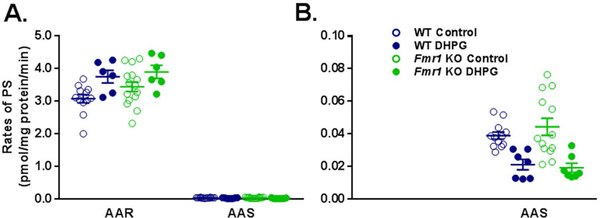

We measured PS rates in slices from both genotypes incubated in AAR or in AAS conditions (see Table 1). The lack of amino acids in the incubation medium drastically reduced the rate of PS by 99% regardless of genotype (Fig. 2A). Under AAR conditions, neither the genotype x condition interaction nor the main effect of genotype was statistically significant (Table 2), but the main effect of DHPG treatment was (p = 0.003). Following DHPG treatment, rates of PS increased 22 and 13% in WT and Fmr1 KO slices, respectively. Similarly, under AAS conditions, neither the genotype x condition interaction nor the main effect of genotype was statistically significant (Table 2) but the main effect of DHPG treatment was (p < 0.001). Treatment with 100 μM DHPG resulted in decreased (46 and 57%) PS rates in slices from both WT and Fmr1 KO, respectively (Fig. 2B). In separate experiments, we confirmed that 95–97% of the incorporation of radiolabeled leucine into the acid precipitable fraction was blocked by treatment with anisomycin in both genotypes under both AAR and AAS conditions (Table S1) indicating that our assay procedure measured de novo PS.

Fig. 2.

Effect of treatment with DHPG (100 μM) on rates of PS in hippocampal slice preparations from WT and Fmr1 KO mice in AAR (A) and in AAS conditions (B). Each point represents the rate measured in one animal. The scale on the ordinate in B. is 1/50th of the scale in A. The number of animals (slices) in each group under AAR was as follows: WT control, n = 12; Fmr1 KO, n = 15; WT DHPG, n = 6; Fmr1 KO DHPG, n = 6. The number of animals (slices) in each group under AAS was as follows: WT control, n = 14; Fmr1 KO, n = 14; WT DHPG, n = 7; Fmr1 KO DHPG, n = 7. Data under each amino acid condition were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype (WT, Fmr1 KO), and treatment (+/− DHPG) as between subject factors (Table 2). Under both conditions, the main effect of treatment was statistically significant (p = 0.003 under AAR, p < 0.001 under AAS). Under AAR conditions treatment with DHPG increased rates of PS and under AAS conditions it decreased rates of PS.

TABLE 2.

Summary of statistical analyses.

| Variable measured | Interaction | Main effect | F(df,error) value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of protein synthesis AAR | Genotype x Treatment | F(1,35)=0.388 | 0.537 | |

| Genotype | F(1,35)=3.281 | 0.079 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,35)=10.053 | 0.003 | ||

| Rate of protein synthesis AAS | Genotype x Treatment | F(1,35)=0.716 | 0.403 | |

| Genotype | F(1,35)=0.447 | 0.508 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,35)=25.37 | <0.001 | ||

| eIF2α | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,62)=1.375 | 0.245 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,62)=0.893 | 0.348 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,62)=0.002 | 0.963 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,62)=0.286 | 0.594 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,62)=14.131 | <0.001 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,62)=1.890 | 0.174 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,62)=0.181 | 0.672 | ||

| p-eIF2 α | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,59)=1.119 | 0.295 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,59)=0.310 | 0.580 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,59)=0.040 | 0.841 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,59)=1.595 | 0.212 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,59)=0.395 | 0.532 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,59)=0.004 | 0.949 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,59)=6.377 | 0.014 | ||

| p-eIF2α/Total eIF2α | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,56)=4.264 | 0.044 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,56)=0.016 | 0.899 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,56)=0.478 | 0.492 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,56)=1.615 | 0.209 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,56)=9.416 | 0.003 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,56)=0.801 | 0.375 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,56)=1.677 | 0.201 | ||

| p70S6k | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,60)=3.097 | 0.084 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,60)=0.609 | 0.438 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,60)=0.153 | 0.697 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,60)=0.128 | 0.722 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,60)=2.610 | 0.111 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,60)=1.762 | 0.189 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,60)=0.357 | 0.552 | ||

| p-p70S6k | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,60)=5.340 | 0.024 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,60)=3.246 | 0.051 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,60)=4.218 | 0.044 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,60)=0.516 | 0.475 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,60)=0.198 | 0.658 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,60)=0.213 | 0.646 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,60)=0.647 | 0.424 | ||

| p-p70S6k/Total | AA condition x genotype x treatment | F(1,56)=4.016 | 0.050 | |

| AA condition x genotype | F(1,56)=0.458 | 0.501 | ||

| AA condition x treatment | F(1,56)=3.869 | 0.054 | ||

| Genotype x treatment | F(1,56)=0.310 | 0.580 | ||

| AA condition | F(1,56)=0.255 | 0.616 | ||

| Genotype | F(1,56)=0.779 | 0.381 | ||

| Treatment | F(1,56)=0.582 | 0.449 | ||

Taken together our results indicate that in the absence of amino acids in the medium, rates of PS are reduced to 1% of rates in the presence of amino acids. In neither AAR nor AAS conditions did we detect a genotype difference in basal rates, but we did find effects of DHPG treatment. The effects of DHPG were present in both genotypes but differed in AAR and AAS conditions.

Effects of group 1 mGluR-activation with DHPG on the mTOR pathway in hippocampal slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice depends on the presence of amino acids in the medium

Signaling through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway is thought to be required for mGluR-dependent LTD in the hippocampal slice (Hou & Klann 2004). Moreover, mTOR activity is reported to be elevated in lysates of hippocampus from young Fmr1 KO mice (Sharma et al. 2010). We examined the abundance of mTOR and the phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser-2448, an indicator of mTOR activity (Hay & Sonenberg 2004) in slices from both genotypes and incubated in either AAR or AAS conditions. For total mTOR and phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser-2448 only the main effects of amino acid condition were statistically significant (Table S1 and Fig. S1). Levels of mTOR (Fig. S1A) and p-mTOR (Fig. S1B) were lower in AAS versus AAR conditions (p < 0.001, p = 0.007, respectively). These results indicate that in the hippocampal slice preparation 3–4 h of AAS conditions lowers mTOR capacity but does so regardless of genotype or treatment. We did not detect genotype differences or effects of DHPG stimulation under either amino acid condition. There were no statistically significant interactions or main effects for the ratio of p-mTOR to total (Fig. S1C).

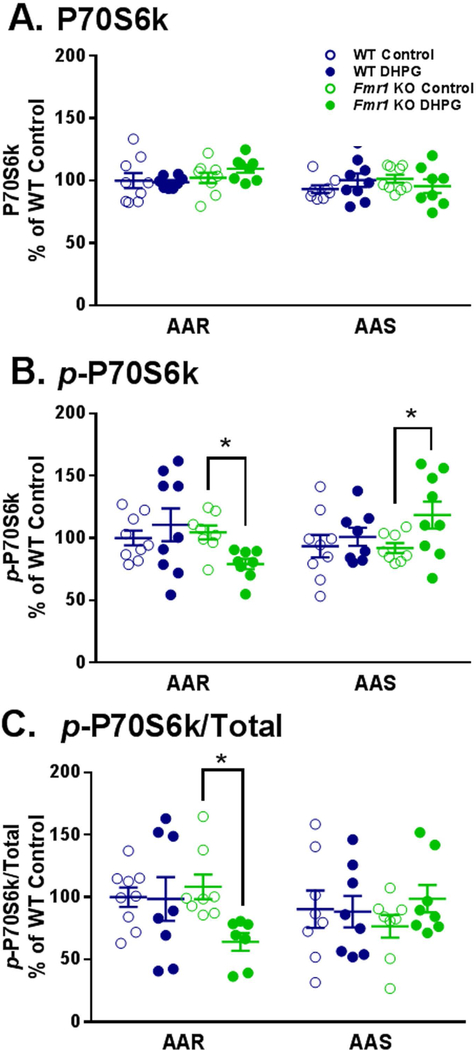

As another marker of mTOR activity, we examined the kinase p70S6k downstream of mTOR for effects of DHPG stimulation. The kinase, p70S6k, is involved in the regulation of ribosomal maturation through its role in catalyzing the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. Phosphorylation of p70S6k at Thr-389 is the site of mTOR-dependent regulation (Burnett et al. 1998). We found no statistically significant effects on abundance of p70S6k (Fig. 3A), but for both p-p70S6k (Thr-389; Fig. 3B) and the ratio of the phosphorylated form to total (Fig. 3C) the amino acid condition x genotype x treatment interactions were statistically significant (Table 2). These results indicate that a genotype-specific response to DHPG is affected by amino acid conditions. In the case of p-p70S6k, treatment with DHPG had no effect on slices from WT mice in either amino acid condition, but in slices from Fmr1 KO mice, DHPG treatment decreased p-p70S6k in AAR conditions (25% of WT, p = 0.042) and increased p-p70S6k in AAS conditions (29% of WT, p = 0.030). A decrease in the ratio of p-p70S6k to total in slices from Fmr1 KO mice in response to DHPG-treatment was also seen (40% of WT, p = 0.013).

Fig. 3.

Effect of treatment with DHPG (100 μM) on levels of p70S6k (A), p-p70S6k (B), and p-p70S6k/Total (C) in hippocampal slice preparations from WT and Fmr1 KO mice in amino acid replete and amino acid starvation conditions. Measurements were made in nine mice for each group. A. In the AAR condition one WT DHPG treated slice and one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice were excluded as outliers. In the AAS condition one WT Control slice was excluded as an outlier, and one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice was excluded because of an artifact on the Western blot. B. In the AAR condition, one Fmr1 KO Control slice and one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice were excluded as outliers. In the AAS condition one WT DHPG treated slice was excluded due to an artifact on the Western blot, and one Fmr1 KO Control slice was excluded as an outlier. C. All exclusions were a result of prior exclusions of either the p-p70S6k or total p70S6k. In the AAR condition, one WT DHPG treated slice, one Fmr1 KO Control slice and two Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slices were excluded. In the AAS condition one WT Control slice, one WT DHPG treated slice, one Fmr1 KO Control slice, and one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice were excluded. Data were analyzed by means of a three-way ANOVA with amino acid condition (AAR, AAS), genotype (WT, Fmr1 KO), and treatment (+/− DHPG) as between subject factors (Table 2). A. For p70S6k, none of the interactions or main effects were statistically significant. B. For p-p70S6k, the amino acid condition x genotype x treatment interaction was statistically significant (p = 0.024). We probed for individual group and condition differences by means of Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-tests. Statistically significant effects are indicated on the figure: *, 0.01 ≤ p ≤ 0.05. C. For p-p70S6k/Total, the amino acid condition x genotype x treatment interaction was statistically significant (p = 0.050). We probed for individual group and condition differences by means of Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-tests. Statistically significant effects are indicated on the figure: *, 0.01 ≤ p ≤ 0.05.

The role of Akt in regulating mTOR and cell growth is complex. Akt is phosphorylated at Thr-308 by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) downstream of PI3K activation (Alessi et al. 1997) and at Ser-473 by mTORC2 (Sarbassov et al. 2005). Activated Akt stimulates mTORC1 by its inhibition of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) which relieves TSC suppression of mTORC1 activity. In our hippocampal slice preparation, we found a statistically significant main effect of genotype (p < 0.001) for total Akt (Fig. S2A), indicating that, regardless of amino acid condition or treatment, slices from Fmr1 KO mice had higher levels of Akt than WT. For p-Akt (Thr-473), levels were higher in AAS conditions regardless of genotype or treatment (Fig. S2B; main effect of amino acid condition, p < 0.001), and levels were higher in slices from Fmr1 KO mice regardless of amino acid condition or treatment (main effect of genotype, p = 0.018). For the ratio of p-Akt to total (Fig. S2C), main effects of both amino acid condition (p < 0.001) and treatment were statistically significant (p = 0.043) indicating higher Akt activation in AAS conditions compared to AAR and decreased activity with DHPG treatment. These results suggest that Akt is activated in AAS conditions likely through mTORC2 signaling and that activation is suppressed with activation of group 1 mGluR receptors likely through feedback by mTORC1.

Another pathway involved in the regulation of cell growth and protein synthesis in response to extracellular cues is the Ras-ERK pathway. There is cross-talk and compensation between the Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways (Mendoza et al. 2011), so it is of interest to consider responses together. Moreover, the ERK pathway has been reported to be implicated in FXS (Osterweil et al. 2010; Osterweil et al. 2013; Sawicka et al. 2016). In our experiment, we found a statistically significant main effect of amino acid condition such that total ERK was lower in AAS compared with AAR regardless of genotype or treatment (Table S1, Fig. S3A). With p-ERK the amino acid condition x treatment interaction was statistically significant indicating that regardless of genotype, p-ERK increased significantly with DHPG treatment in AAS conditions (p < 0.001, Table S1, Fig. S3B); effects in AAR conditions were not statistically significant. Regardless of genotype p-ERK was statistically significantly increased in AAS compared with AAR conditions with (p < 0.001) and without (p < 0.001) DHPG treatment. The treatment x amino acid condition interaction was statistically significant for the ratio of p-ERK to total (p = 0.001) (Fig. S3C). In this case, increases with DHPG treatment regardless of genotype were statistically significant under both AAS (p < 0.001) and AAR (p = 0.040) conditions, but effects were greater in the AAS condition. Ratios of p-ERK to total were higher in AAS conditions compared to AAR regardless of genotype with (p < 0.001) and without (p = 0.001) DHPG. Differences were greater with DHPG treatment.

Effects of group 1 mGluR-activation with DHPG on phosphorylation of eIF2α in hippocampal slices from control and Fmr1 KO mice depends on the presence of amino acids in the medium

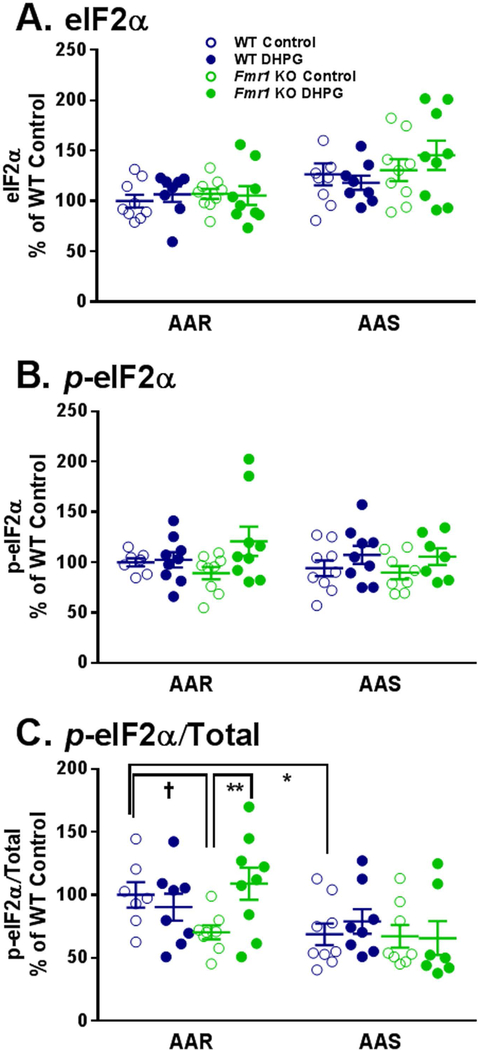

General protein synthesis is suppressed in response to diverse forms of stress through the phosphorylation of eIF2α (Pain 1996). Phosphorylation of eIF2α by one of several kinases generates the integrated stress response which in addition to decreasing general protein synthesis also increases translation of a subset of transcripts containing upstream open reading frames (uORF). One of the stressors known to induce this response is a limitation in availability of amino acids through general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) which senses uncharged tRNAs. Other kinases acting on eIF2α are double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), hemin-regulated inhibitor kinase (HRI), and misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (PERK). Work from the Sonenberg lab reports that phosphorylation of eIF2α is involved in the long-term phase of LTP (Costa-Mattioli et al. 2009). The hippocampal response to group 1 mGluR activation and the late phase of LTD is also thought to involve phosphorylation of eIF2α (Di Prisco et al. 2014). We measured eIF2α activity in lysates of hippocampal slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice under the AAR and AAS conditions with and without treatment with DHPG. For total eIF2α (Fig. 4A) and p-eIF2α (Fig.4B), only the main effects of amino acid condition (p < 0.001) and DHPG treatment (p = 0.014), respectively, were statistically significant. For the p-eIF2α/total response, the amino acid condition x genotype x treatment interaction was statistically significant, so we probed for individual differences (Table 2, Fig. 4C). With AAR, the ratio of p-eIF2α to total under basal conditions was lower in slices from Fmr1 KO mice compared to WT (30% of WT, p = 0.051). Moreover, in AAR conditions the response to DHPG differed between WT and Fmr1 KO mice. Whereas slices from WT mice were unaffected by DHPG, p-eIF2α/total increased (by 50% of basal, p = 0.008) with DHPG treatment in slices from Fmr1 KO mice. In AAS, we found no effects of DHPG on p-eIF2α/total in either genotype.

Fig. 4.

Effect of treatment with DHPG (100 μM) on levels of eIF2α (A), p-eIF2α (B), and p-eIF2α/Total (C) in hippocampal slice preparations from WT and Fmr1 KO mice in AAR and AAS conditions. Measurements were made in nine mice for each group. A. One WT DHPG treated slice was excluded from both the AAR and the AAS conditions as an outlier. B. In the AAR condition, two WT Control slices and in the AAS condition one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice were excluded due to artifacts on Western blots. In AAS, one Fmr1 KO Control slice and one Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slice were excluded as outliers. C. All exclusions were a result of prior exclusions of either the p-eIF2α or total eIF2α. In the AAR condition, two WT Control slices and one WT DHPG treated slice were excluded. In the AAS condition, one WT DHPG treated slice, one Fmr1 KO Control slice, and two Fmr1 KO DHPG treated slices were excluded. Data were analyzed by means of a three-way ANOVA with amino acid condition (AAR, AAS), genotype (WT, Fmr1 KO), and treatment (+/− DHPG) as between subject factors (Table 1). A. For eIF2α, the main effect of amino acid condition was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that regardless of genotype or treatment levels of eIF2α are higher in AAS conditions. B. For p-eIF2α, the main effect of treatment was statistically significant (p = 0.014), indicating that regardless of genotype or amino acid conditions DHPG resulted in an increase in p-eIF2α. C. For p-eIF2α/Total, the amino acid condition x genotype x treatment interaction was statistically significant (p = 0.044). We probed for individual group and condition differences by means of Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-tests. Statistically significant effects are indicated on the figure: †, 0.05 ≤ p ≤ 0.10; *, 0.01 ≤ p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 ≤ p ≤ 0.01.

Considering the effect on p-eIF2α we examined one of the kinases known to phosphorylate eIF2α, GCN2 (Table S1, Fig S4). The only statistically significant effect on GCN2 was a main effect of amino acid condition on the ratio of p-GCN2 to total indicating that in AAS conditions the ratio decreases regardless of genotype or treatment (Fig. S2C). This result is in accord with the lack of activation of eIF2α following 4–5 h of AAS conditions (Fig. 4C).

Effects of group 1 mGluR-activation with DHPG on LTD in hippocampal slices from control and Fmr1 KO mice depends on the presence of amino acids in the medium

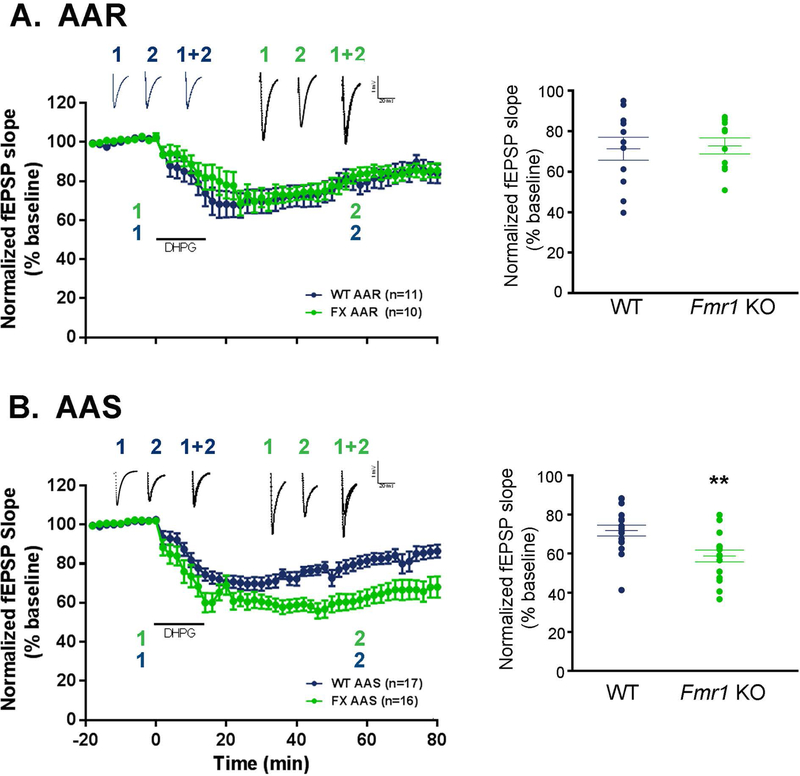

Previous research has shown that DHPG-induced, group 1 mGluR-dependent LTD is enhanced in Fmr1 KO hippocampal slices (Huber et al. 2002). mGluR-dependent LTD is a complex process that is dependent on PS (Huber et al. 2000). Therefore, it is likely that absence of amino acids in the medium may influence this type of LTD. We examined this question in hippocampal slice preparations from WT and Fmr1 KO mice that were maintained in AAS or AAR condition. In both WT and Fmr1 KO slices, fEPSPs decreased after DHPG treatment regardless of AAR or AAS, indicating that LTD is induced. The genotype x amino acid condition x epoch interaction was not statistically significant (F(4.143,207.129) = 1.441, p = 0.22), but the genotype x amino acid condition interaction was (F(1,50) = 5.523, p = 0.023; Fig. 5). Further testing indicates that, regardless of epoch, there was no difference in DHPG-induced LTD in WT slices between AAR and AAS (mean fEPSPs between 50–60 min post DHPG treatment: WT-AAR = 71% and WT-AAS = 72% of baseline; p = 0.950; Fig. 5). In contrast, in Fmr1 KO slices, fEPSPs after DHPG treatment were statistically significantly lower in AAS than in AAR (mean fEPSPs between 50–60 min post DHPG treatment: Fmr1 KO-AAR = 72% and Fmr1 KO-AAS = 59% of baseline; p = 0.002; Fig. 5), indicating that LTD is enhanced in AAS condition. In AAS, the fEPSP decrease after DHPG treatment was greater in Fmr1 KO slices than in WT slices (mean fEPSPs between 50–60 min post DHPG treatment: WT-AAS = 72 % and Fmr1 KO-AAS = 59% of baseline; p = 0.004; Fig. 5), while in AAR, the fEPSP decrease was comparable in WT and Fmr1 KO slices (mean fEPSPs between 50–60 min post DHPG treatment: WT-AAR = 71% and Fmr1 KO-AAR = 71% of baseline; p = 0.568; Fig. 5). These results confirm the previous finding that in AAS, LTD is enhanced in slices from Fmr1 KO compared to WT slices (Huber et al. 2002). By contrast, under more physiological conditions (AAR), there is no difference between Fmr1 KO and WT in DHPG-induced LTD (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

DHPG-induced LTD in Fmr1 KO and WT mice under AAR (A) and AAS (B) conditions. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of fEPSP slope as a percent of baseline for the number of slice preparations indicated on the figure. The number of slices from which recordings were obtained were 17 from 12 WT mice under AAS, 16 from 14 Fmr1 KO mice under AAS, 11 from 11 WT mice under AAR, 10 from 5 Fmr1 KO mice under AAR. The time courses of epoch-binned data were compared between WT and Fmr1 KO mice in AAS and AAR by means of a three-way repeated measures ANOVA. The genotype x amino acid condition x epoch interaction was not statistically significant (F(4.143,207.129) = 1.441, p = 0.22), but the genotype x amino acid condition interaction was (F(1,50) = 5.523, p = 0.023). Further testing indicates that regardless of epoch, the difference between WT and Fmr1 KO was statistically significant in AAS (p = 0.004) but not in AAR (p = 0.568). Regardless of epoch, there was no difference in WT between fEPSPs as percent of baseline in AAR and AAS (p = 0.950). In contrast, in Fmr1 KO the fEPSPs as percent of baseline after DHPG treatment in AAS was statistically significantly lower (p = 0.002) than those in AAR. Representative waveforms of CA1 pyramidal cell depolarization following Schaffer collateral activation are shown in the insets of each graph. Lines (1) denote baseline waveforms while lines (2) denote waveforms 50 min after DHPG induced LTD. Waveforms are the average of 12 sweeps during recordings.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate hippocampal slices from WT and Fmr1 KO mice under AAR conditions. The presence of amino acids in aCSF more closely mimics physiological conditions and is the relevant condition for understanding in vivo states. Addition of amino acids to the incubation media is especially important in studies of PS-dependent processes in hippocampal slices. Research in yeast has characterized the stress response that results from AAS. This stress response leads to alterations in cellular growth pathways and an inhibition in cap-dependent translation which is also involved in synaptic processes such as mGluR-dependent LTD (Yang et al. 2016; Di Prisco et al. 2014). In the current experiment, exploration of how the presence of amino acids affects PS-dependent processes in Fmr1 KO mice revealed distinct effects on general rates of PS, activation of cellular growth proteins, and mGluR-dependent LTD.

The presence or absence of amino acids in aCSF has a profound effect on general rates of PS. A lack of amino acids in aCSF reduced overall rates in WT and Fmr1 KO hippocampal slices to about 1% of rates in AAR aCSF. The effect suggests potential alterations in any process associated with or dependent on PS in AAS. Indeed, DHPG activation of group 1 mGluRs had amino acid-dependent effects on PS. In the presence of amino acids, DHPG increased general rates of PS, whereas in the absence of amino acids DHPG decreased general rates of PS. These results show that the integrated stress response to the lack of amino acids likely influences the downstream synthesis of proteins activated by group 1 mGluR activation. The amino acid condition also affected LTD and did so in a differential manner between the two genotypes. Elevated mGluR-dependent LTD in Fmr1 KO hippocampal slices in AAS is a well-established phenotype of Fmr1 KO mice (Huber et al. 2002). In slices from WT animals, mGluR-dependent LTD is dependent on de novo protein synthesis (Huber et al. 2000), whereas in slices from Fmr1 KO mice it is not (Nosyreva & Huber 2006). This result was interpreted to indicate that “LTD proteins” were already in excess at the synapse due to dysregulated PS allowing LTD to persist in the absence of newly synthesized proteins. In the light of our present study, we think that all these results were influenced by the integrated stress response provoked by the AAS conditions of the experiments.

We considered that the lack of enhanced mGluR-dependent LTD in Fmr1 KO slices in the presence of amino acids was due to differential activity of signaling pathways regulating PS. In support of differential effects on signaling pathways is our observation that PS increased with DHPG treatment in AAR and decreased with DHPG treatment in AAS. One of the most likely candidates is through regulation of the phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine-51. eIF2α is part of the regulatory subcomplex of eIF2B, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, that regulates the formation of the ternary complex (eIF2 • GTP • Met-tRNA) and therefore initiation of cap-dependent translation. Phosphorylation of eIF2α is a critical step in the integrated stress response. In the hippocampal slice in AAR and under basal conditions, phosphorylation of eIF2α is lower in slices from Fmr1 KOs compared to WT. With DHPG treatment, phosphorylation of eIF2α is elevated over basal in Fmr1 KOs but not in WT. This result implies that regulation of translation initiation by eIF2 is altered in Fmr1 KOs. It is conceivable that tight local control of translation by FMRP is especially critical with activation of mGluRs. In the Fmr1 KO, this system of local control is lost and may be supplanted by an integrated stress response. Phosphorylation of eIF2α in slices from Fmr1 KO mice following DHPG treatment is in accord with this scenario. Moreover, the decrease in p-p70S6k activity suggests that other systems are also working to quell an unbridled PS response.

Our study provides an overview of the effects of amino acid conditions on phenotypes observed in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice. We have not, in this initial report, done a comprehensive study of all possible parameters and mechanisms underlying these phenotypes. Our electrophysiological studies did not address possible genotype and condition differences in baseline responses and in paired-pulse facilitation responses. These properties have been investigated previously (Parradee et al., 1999; Huber et al., 2002) and found not to be appreciably affected by a lack of FMRP in the mouse. Whereas these properties have not been investigated in slices incubated in medium containing amino acids, it seems unlikely that the presence or absence of amino acids would affect the protein synthesis-independent properties. The effects of AAR conditions on these responses will be the subject of future investigations. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that the presence or absence of amino acids in the incubation medium will affect the measured LTD response in Fmr1 KO slices.

Our report brings to light several key methodological differences that have large effects on results of studies of PS and PS-dependent processes. First and foremost is the presence of amino acids in the incubation media. Another difference is the use of an inhibitor of transcription. We did not include actinomycin-D in our incubation medium, because we did not wish to eliminate control through the synthesis of transcription factors. Actinomycin-D was included in the media of experiments in which an increase in PS in slices from Fmr1 KO mice was reported in AAS (Dölen et al. 2007; Osterweil et al. 2010). Phosphorylation of eIF2α results in inhibition of general PS at the same time instituting translation of a set of mRNAs with ORFs. These include transcription factors including ATF4 (or CREB2), ATF6, CHOP, XBP-1 and others known to induce transcription of genes coding for endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and enzymes to cope with an excess of unfolded proteins or a lack of amino acids (Wek et al. 2006). In previous studies (Osterweil et al. 2010), treatment with DHPG occurred in the presence of amino acid tracer, capturing the early PS response to DHPG. Under these conditions DHPG was seen to increase PS in WT slices, but it did not affect PS in Fmr1 KO slices. The early response to DHPG treatment may have a disproportionate effect on the measured PS response and may account for our measurement of a decreased rate of PS in AAS with DHPG treatment.

A puzzling result is our observation that neither p-GCN2 nor p-eIF2α increased in AAS conditions compared with AAR. As GCN2 is known to sense AAS and eIF2α is the direct target of GCN2 activity these results are the opposite of the reported roles these proteins play in the integrated stress response to amino acid deficit. It is possible that the lack of activation of GCN2 and eIF2α is due to the amount of time hippocampal slices were maintained in AAS. In studies of mouse embryonic stem cells, it was shown that the phosphorylation of eIF2α lessened over time during leucine deprivation (Zhang et al. 2002). It is possible that a similar mechanism is occurring here. There may have been an immediate increase in the activity of GCN2 and eIF2α in response to the absence of amino acids that dissipated over the 4–5 h incubation period. This could explain why it was observed that protein synthesis did not reach stable levels until 4 hours after incubation in Standard aCSF lacking amino acids (Osterweil et al. 2010). Future experiments will need to examine the time course of activity of GCN2 and eIF2α in hippocampal slices during the recovery period following slice preparation in AAS and AAR conditions.

Another important concern is that the current experiment did not replicate previously seen increases in global rates of PS in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice. Increased rates of global PS in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice have been shown both in vivo (Qin et al. 2005) and in vitro (Osterweil et al. 2010) in hippocampal slices, whereas in the present study we saw no genotype differences in PS under either amino acid condition. One consideration is the use of anesthesia. In the present study, mice were euthanized by rapid decapitation; no anesthesia was used. Previous in vivo PS measurements were made in mice after surgical implantation of vascular catheters; surgery was carried out under isoflurane anesthesia 24 h prior to measurements (Qin et al. 2005). In previous in vitro studies, hippocampi were dissected after mice were given an overdose of Nembutal (Osterweil et al. 2010). Our study of the effects of propofol anesthesia on PS rates measured in vivo indicated that Fmr1 KO, but not WT, mice respond to propofol anesthesia with altered rates of global PS (Qin et al. 2013). Moreover, work of others has shown lasting effects of quickly cleared anesthetics such as isoflurane and halothane in WT mice on the activation of proteins such as ERK, mTOR, eIF2α, and p70S6K (Qin et al. 2013; Antila et al. 2017; Kang et al. 2017; Palmer et al. 2005). These proteins are involved in the regulation of PS and are thought to be involved in the group 1 mGluR response. The use of anesthetics may confound results of experiments designed to measure effects of lack of FMRP on PS and PS-dependent processes.

Our studies call for a re-examination of the mGluR theory of FXS. Whereas our present results do not show enhanced DHPG-induced LTD in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice under normal physiological conditions (AAR), they do show that the response to DHPG stimulation is abnormal in other respects. In Fmr1 KO slices, the response to DHPG includes phosphorylation of eIF2α indicating that an integrated stress response has been mounted. We propose that this integrated stress response may be a cellular attempt to compensate for the lack of regulation of translation by FMRP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Zengyan Xia for genotyping the mice.

Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH, ZIA MH0088936 and ZIA MH002882.

Abbreviations:

- FXS

fragile X syndrome

- FMRP

fragile X mental retardation protein

- mGluR5

metabotropic glutamate receptor 5

- LTD

long term depression

- eIF2

eukaryotic initiation factor 2

- eIF2α

alpha subunit of eIF2

- KO

knockout

- RGG

arginine/glycine-rich RNA-binding region

- rCPS

rate of cerebral protein synthesis

- WT

wild type

- DHPG

dihydroxyphenylglycine

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- Akt

protein kinase B

- AAR

amino acid replete

- AAS

amino acid starvation

- PS

protein synthesis

Footnotes

Data and materials availability: N/A.

Laboratory of origin: Section on Neuroadaptation and Protein Metabolism, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- Alessi DR, Deak M, Casamayor A et al. (1997) 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1): structural and functional homology with the Drosophila DSTPK61 kinase. Current biology : CB 7, 776–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antila H, Ryazantseva M, Popova D et al. (2017) Isoflurane produces antidepressant effects and induces TrkB signaling in rodents. Sci Rep 7, 7811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley CT Jr., Wilkinson KD, Reines D and Warren ST (1993) FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science 262, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, Huber KM and Warren ST (2004) The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci 27, 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett PE, Barrow RK, Cohen NA, Snyder SH and Sabatini DM (1998) RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95, 1432–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E and Sonenberg N (2009) Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron 61, 10–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco GV, Huang W, Buffington SA et al. (2014) Translational control of mGluR-dependent long-term depression and object-place learning by eIF2α. Nature neuroscience 17, 1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dölen G, Osterweil E, Rao BS, Smith GB, Auerbach BD, Chattarji S and Bear MF (2007) Correction of fragile X syndrome in mice. Neuron 56, 955–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Absher D, Eberhart DE, Brown V, Malter HE and Warren ST (1997) FMRP associates with polyribosomes as an mRNP, and the I304N mutation of severe fragile X syndrome abolishes this association. Molecular Cell 1, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N and Sonenberg N (2004) Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev 18, 1926–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou LF and Klann E (2004) Activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-akt-mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway is required for metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression. Journal of Neuroscience 24, 6352–6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST and Bear MF (2002) Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, 7746–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Kayser MS and Bear MF (2000) Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science 288, 1254–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Jiang D, Ryu YK et al. (2017) Early postnatal exposure to isoflurane causes cognitive deficits and disrupts development of newborn hippocampal neurons via activation of the mTOR pathway. PLoS Biol 15, e2001246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laggerbauer B, Ostareck D, Keidel EM, Ostareck-Lederer A and Fischer U (2001) Evidence that fragile X mental retardation protein is a negative regulator of translation. Human Molecular Genetics 10, 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Ku L, Wilkinson KD, Warren ST and Feng Y (2001) The fragile X mental retardation protein inhibits translation via interacting with mRNA. Nucleic acids research 29, 2276–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza MC, Er EE and Blenis J (2011) The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci 36, 320–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyreva ED and Huber KM (2006) Metabotropic receptor-dependent long-term depression persists in the absence of protein synthesis in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurophysiol 95, 3291–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Chuang SC, Chubykin AA, Sidorov M, Bianchi R, Wong RK and Bear MF (2013) Lovastatin corrects excess protein synthesis and prevents epileptogenesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neuron 77, 243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K and Bear MF (2010) Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 30, 15616–15627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain VM (1996) Initiation of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells. Eur J Biochem 236, 747–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LK, Shoemaker JL, Baptiste BA, Wolfe D and Keil RL (2005) Inhibition of translation initiation by volatile anesthetics involves nutrient-sensitive GCN-independent and -dependent processes in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 16, 3727–3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Kang J, Burlin TV, Jiang C and Smith CB (2005) Postadolescent changes in regional cerebral protein synthesis: an in vivo study in the FMR1 null mouse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 25, 5087–5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Schmidt KC, Zametkin AJ et al. (2013) Altered cerebral protein synthesis in fragile X syndrome: studies in human subjects and knockout mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33, 499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM and Sabatini DM (2005) Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307, 1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicka K, Pyronneau A, Chao M, Bennett MV and Zukin RS (2016) Elevated ERK/p90 ribosomal S6 kinase activity underlies audiogenic seizure susceptibility in fragile X mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, E6290–E6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Hoeffer CA, Takayasu Y, Miyawaki T, McBride SM, Klann E and Zukin RS (2010) Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi H, Siomi MC, Nussbaum RL and Dreyfuss G (1993) The Protein Product of the Fragile-X Gene, Fmr1, Has Characteristics of an Rna-Binding Protein. Cell 74, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek RC, Jiang HY and Anthony TG (2006) Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem Soc Trans 34, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Zhou X, Zimmermann HR, Cavener DR, Klann E and Ma T (2016) Repression of the eIF2alpha kinase PERK alleviates mGluR-LTD impairments in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 41, 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, McGrath BC, Reinert J et al. (2002) The GCN2 eIF2 Kinase Is Required for Adaptation to Amino Acid Deprivation in Mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22, 6681–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.