Abstract

Alkylphosphocholine (APC) analogs are a novel class of broad-spectrum tumor-targeting agents that can be used for both diagnosis and treatment of cancer. The potential for clinical translation for APC analogs will strongly depend on their pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles. The aim of this work was to understand how the chemical structures of various APC analogs impact binding and PK. To achieve this aim, we performed in silico docking analysis, in vitro and in vivo partitioning experiments, and in vivo PK studies. Our results have identified 7 potential high-affinity binding sites of these compounds on human serum albumin (HSA) and suggest that the size of the functional group directly influences the albumin binding, partitioning, and PK. Namely, the bulkier the functional groups, the weaker the agent binds to albumin, the more the agent partitions onto lipoproteins, and the less time the agent spends in circulation. The results of these experiments provide novel molecular insights into the binding, partitioning, and PK of this class of compounds and similar molecules, as well as suggests pharmacological strategies to alter their PK profiles. Importantly, our methodology may provide a way to design better drugs by better characterizing PK profile for lead compound optimization.

Keywords: Molecular imaging, in silico modeling, pharmacokinetics, theranostics

Introduction

The plasma binding properties of a drug are of vital importance because they affect the pharmacokinetic properties such as rates of uptake and clearance, and impacts clinical efficacy and safety. Drug binding to serum proteins impacts the rate of clearance and uptake by target tissues, as only the unbound drug is taken up by metabolic or target tissues1–3. Consequently, a high affinity for plasma proteins may be beneficial or detrimental depending on the drug’s clinical indications. Very high binding affinity may be detrimental if there are off-target effects, since long systemic circulation may increase the exposure time and lead to dose-limiting toxicities such as myelosuppression commonly seen with long circulating antibody therapies4–7. Very low levels of binding may result in rapid clearance, and result in low levels of target tissue delivery.

Even after demonstrating preclinical efficacy, only a small percentage of anticancer drugs (5%) are approved by the Food and Drug Administration8. Non-optimal pharmacokinetic profiles are primary contributors to regulatory attrition (39%)9–10. Therefore, in silico modeling that is predictive of pharmacokinetic behavior based on chemical composition and physicochemical properties represents a powerful and economical approach to designing drug analogs with more favorable characteristics10–12. Importantly, lead compound optimization of pharmacokinetic properties will drastically improve the successful development of these anticancer compounds8. In silico modeling can identify lead compounds more quickly than classical methods. Therefore, we developed a methodology to study protein binding and serum partitioning of alkylphosphocholine analogs (APC) analogs and related compounds to facilitate its optimization for clinical applications. We characterized the serum protein binding for diagnostic and therapeutic APC analogs using a multifaceted approach of in silico docking analysis, and performed corroborative partitioning and pharmacokinetic studies for insights into better next generation drug design13–15. In addition, we describe the development of a novel in silico methodology that is specific to characterizing human serum albumin binding to lipophilic compounds. This methodology may be generally useful in achieving better pharmacokinetics and safety profiles for future lipophilic drugs, and offer insights into pharmacological strategies that alter the pharmacokinetics of lipoprotein-bound drugs13–14, 16.

Alkylphosphocholine (APC) analogs are a class of compounds that exhibit long plasma residence times due to tight binding to serum proteins that result in slow clearance rates. These APC analogs have strong clinical potential because they exhibit broad-spectrum tumor- targeting and possess multimodal diagnostic imaging and therapy potential17–21. Currently, a suite of APC analogs are in preclinical and clinical development for diagnostic positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, near-infrared (NIR) intraoperative detection, and targeted radiotherapy for multiple cancer types, and more analogs are under development for other diagnostic imaging modalities and targeted chemotherapy delivery18–25. However, the pharmacokinetic profiles of these APC analogs have not been formally optimized. Increasing the rate of clearance and uptake of these imaging and therapy compounds to allow for faster imaging, as well as larger therapeutic windows may improve the efficacy and safety of these APC analogs facilitating clinical approval. In addition, the serum protein binding characteristics are not well understood for this class of agents and warrant further investigation. A better understanding of how these structures affect protein binding may yield important insights into smarter drug design of diagnostic imaging and therapy agents that have pharmacokinetic tailored profiles. These analogs may be used to develop predictive models and establish important behaviors for similar lipophilic compounds.

The binding of APC analogs and structurally related Alkylphospholipid (APL) analogs to serum proteins have been reported in scientific literature15, 26–28. However, the purported binding sites and partitioning characteristics have not been well characterized. APC analogs bear a striking resemblance to endogenous fatty acids. The binding of fatty acids to plasma proteins have been well characterized, and they predominantly bind to several distinct sites on albumin29–33. Moreover, crystal structure analyses of monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and fatty acid-like molecules such as lysophosphatidylcholine display binding to these same albumin pockets despite structural dissimilarities between these classes of compounds26, 34. These albumin binding sites are well conserved between mammalian species, although it has been reported that fatty acids bind to these pockets with less affinity on murine serum albumin35. These data suggest that the binding of these fatty acid-like molecules is in well-conserved binding pockets, and minor alterations of these compounds do not affect gross binding characteristics. Moreover, evidence suggests as fatty acid chain length increases, more partitioning is observed into the lipoprotein layer36–37. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that there is an indirect correlation between drug-affinity for FA sites on albumin at and lipoprotein affinity for APCs and structurally similar compounds.

We hypothesized that these APC analogs exhibit binding properties similar to endogenous fatty acids, and further explored their partitioning characteristics. We used a combination of in silico docking methods, experimental binding assays, partitioning assays, and PK studies to interrogate the structure-binding relationship and attempt to predict residence times of APC agents based on albumin docking energies. Our methodology may be generalized to facilitate drug optimization of lipophilic compounds which display similar characteristics.

Materials and Methods

APC analogs

NM404 (18-(p-Iodophenyl)octadecylphosphocholine), 1501 (18-[p-(4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-8-yl)-phenyl]-octadecyl phosphocholine), 1502 (1,3,3-trimethyl-2-[(E)-2-[(3E)-3-(2-[(2E)-1,3,3-trimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidene]ethylidene}−2-[4-(18-([2-(trimethylazaniumyl)ethyl hosphonato]oxy)octadecyl)phenyl]cyclohex-1-en-1-yl]ethenyl]-3H-indol-1-ium), were provided by Cellectar Biosciences, Inc. (Madison, WI). Their synthesis was previously reported17. Roughly 0.05mg/mL of the APC analogs were used for plasma partitioning studies. NM404 was labeled with 124Iodine via isotope exchange reaction as previously reported38.

Ultracentrifugation

Fresh murine plasma was obtained from athymic nude mice and fresh human unfrozen plasma was purchased from Zenbio (Cat #: SER-PLE10ML), and incubated with APC analogs compounds obtained from Cellectar Biosciences Inc, in separate glass tubes and incubated and shaken for 4hrs at 37°C. Samples were transferred to ultracentrifuge columns (Beckman Cat#: 344090) and tubes were spun at 250g for 8 hrs in Beckman Coulter L-60 Ultracentrifuge39–41. Samples were then carefully removed and the three phases were separated and imaged using Xenogen IVIS Imaging System 100 for fluorescence or the 2480 Automatic Gamma Counter from PerkinElmer for radioactivity or the to determine signal intensity in each layer.

Native Gel Electrophoresis

Fresh human unfrozen plasma was purchased from Zenbio (Cat #: SER-PLE10ML), and incubated with different APC compounds in separate Eppendorf tubes and incubated and shaken for 4hrs at 37°C. Samples were mixed with sample buffer (BioRad Cat#: 161–0738) and were run in non-denaturing conditions and in Tris-Glycine gels (Biorad Cat#: 456–1024, 161–1158). All gels were run under the same voltage and for the same duration. The position of the signal and the band intensities were determined using the Xenogen IVIS Spectrum imaging system under the well plate setting for fluorescence signals, and also BioScan AR2000 for radioactivity signals. Bands were then Coommassie stained (Protea SB-G250X). SeeBlue Plus2 Prestained standard from life technologies (Cat#: LC5925), mouse albumin from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: A3139), low-density human lipoprotein from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: L7914), high-density human lipoprotein from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: L8039), human gamma-globulins from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: G4286), human alpha1-acid glycoprotein from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#:G9885), fatty acid free human serum albumin from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: A3782) were used as standards.

Albumin Spectrofluorescence Assay

Excitation scans and emission scans of human serum albumin fatty acid free (Cat# A3782) in phosphate buffered saline were obtained at 37°C using the Tecan Safire II42. Myristic acid (Cat # M3128) at different molar concentrations were allowed to bind to human serum albumin and monitored via kinetic analysis mode at the emission wavelengths determined from previous experiment on the Tecan Safire II. After 10 minutes, APC was injected and monitored via kinetic analysis mode on the Tecan Safire II.

Equilibrium Dialysis

Rapid equilibrium dialysis device (Cat # 90006) and well inserts (Cat # 89810) were purchased from ThermoScientific43. Fatty acid free human serum albumin from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: A3782) was dissolved in PBS and placed in the equilibrium dialysis chamber, and PBS was added to the collection well. The device was allowed to incubate on a shaker at 37°C during which small aliquots were taken from the collection well. Samples were analyzed via NanoDrop 200c for UV detection or 2480 Automatic Gamma Counter for radioactivity to determine concentration.

In Silico Docking Studies

Crystal structures of human serum albumin containing stearic acid was obtained from the RCSB Protein Databank (PDB ID: 1EI7)30. The ligands were removed from the albumin crystal structure using gedit version 2.30.2, while new APC ligands were created using Marvin v15.9.14.0 (2015) from ChemAxon and converted to the appropriate format using OpenBabel v2.3.1. The APC ligands were docked to albumin globally and also specifically to the sites previously occupied with fatty acids or similar lipophilic molecules using Autodock Vina v1.1.244–45. Each ligand was docked to each specific docking site ten times and docking energies from these runs were averaged. Figures and videos were made with PyMol v1.7.6. Nonspecific binding energies were quantitated by docking the APC ligands to human serum albumin with ligands occupying the fatty acid binding sites. This particular methodology was employed because these compounds partition to lipoproteins, which signifies that non-specific surface binding molecules have more access to lipoproteins in plasma, but not buried proteins in the binding sites. Due to the similarities of docking conformations, the average docking energies and SEMs were calculated after normalizing to non-specific binding energies.

Pharmacokinetic modeling

Concentration versus time data for NM404, 1501, and 1502 were analyzed by non-compartmental analysis to determine clearance, mean residence times, area under the curve, and area under the first moment curve. Calculations were normalized to the starting doses of compounds.

Log D determination

124I-NM404, 1501, and 1502 were added to octanol (Sigma-Aldrich 472328) and allowed to equilibrate overnight. Equal volumes of distilled water constituted at pH 7.4 were added and the mixture was rotated at room temperature shielded from light for 48hrs. The octanol and water phases were separated and analyzed using the gamma counter for 124I-NM404 or Tecan Safire II for optically active 1501 and 1502 to determine relative concentrations.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

All studies were performed in athymic, nude mice, with body weights ranging from 20–26g. Eighteen nude athymic mice were used for studies assessing the pharmacokinetic impact of different functional moieties. APC analogs for injection were prepared and formulated as previously reported17. Injected dose was normalized to the mass of radiolabeled compound and bodyweight of the animal in order to maintain consistency of injected mass dose between animals in comparative studies. Optical analogs, 1501 and 1502, were intravenously injected into mice at quantities of 2.6μmol/kg, which is within the range of dosage used for past animal studies46. Care of animals and all experimental protocols and methods were approved and in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12hr light/dark cycle, and were fed a standard rodent chow containing 6.2% fat, mostly polyunsaturated (Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet, Envigo). Free access to food and water was permitted prior to experiments. Prior to studies, blood was collected from each mouse to normalize for background fluorescence signal and radioactivity signal. The mice were injected with different APC compounds via tail-vein injection. Small amounts of blood were collected via maxillary puncture into EDTA vials. Concentrations of compound were determined using Tecan Safire II spectrophotometer or using the 2480 Automatic Gamma Counter from PerkinElmer.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel version 15.0.4779.1002 or GraphPad Prism 5.0. Ten simulations for each fatty acid pocket were performed for each APC analog, and repeated measures ANOVA, and paired t-Tests were calculated to determine differences in docking between APC analogs. All p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Numbers of experiments and mice used are indicated. A total of 18 nude athymic mice were used for pharmacokinetic studies assessing the impact of the functional moiety.

Results

APC analogs share similar targeting moiety, but differ in their functional moiety

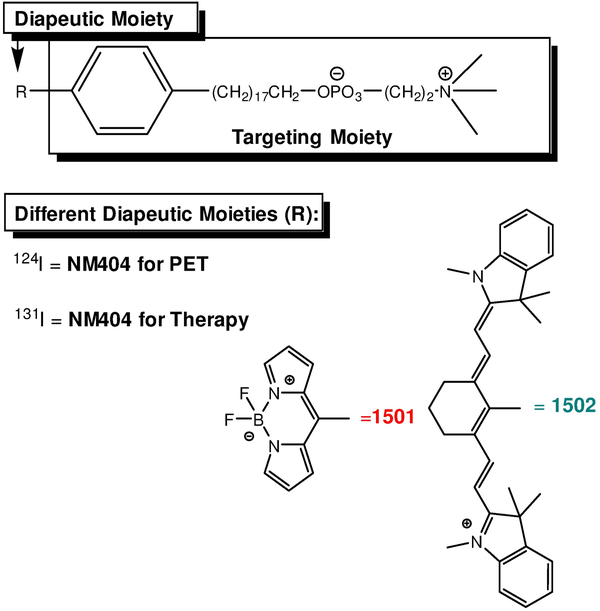

The structures of the APC analogs are shown in figure 1. The targeting group consists of an alkyl chain and a phosphocholine polar head. NM404 derivatives including 124I-NM404, 131I-NM404, 1501, and 1502 share a targeting alkylphosphochline moiety consisting of 18 carbon alkyl chain (Figure 1). Addition of different functional moieties confers different diagnostic and therapeutic qualities.

Figure 1.

Structures of different analogs of alkylphosphocholine analogs and their clinical uses. Structures of 1501, 1502, and NM404.

APC analogs bind primarily to the serum albumin and lipoproteins

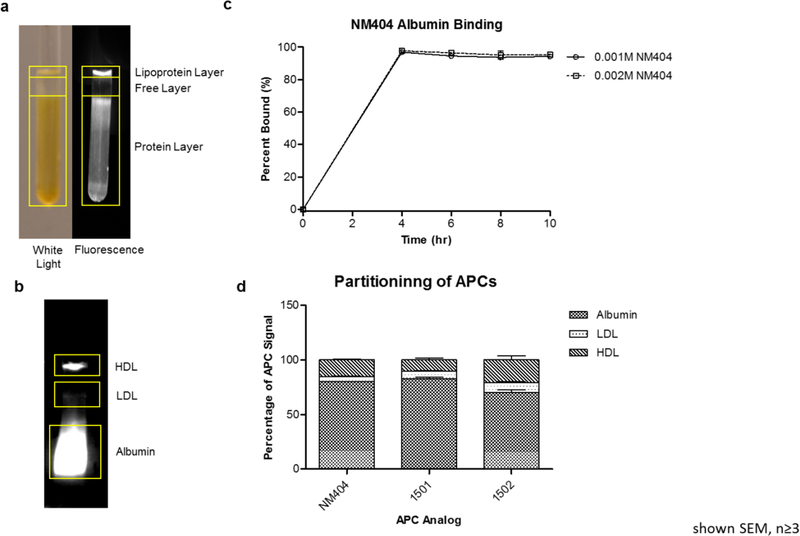

Partitioning studies using human plasma indicate binding of APC analogs primarily to two distinct layers after ultracentrifugation. Fresh, unfrozen human plasma was incubated with different APC analogs (100nM) at 37°C for 4 hours with stirring. The samples were then either ultracentrifuged or separated via native gel electrophoresis to determine partitioning of these compounds to different plasma components (Figure 2)40. APC analogs primarily segregated to the protein layer and the low density lipoprotein layer, but very little remained in the free layer (Figure 2A). Native gel electrophoresis indicates binding of the APC analogs to high density lipoprotein (HDL) and low density liproprotein (LDL), and the main protein component albumin (Figure 2B). No appreciable binding was seen to alpha-acid glycoprotein, gamma globulins, or erythrocytes (data not shown). Furthermore, equilibrium dialysis revealed high affinity (96%) binding of 124I-NM404 to fatty acid-free human serum albumin (HSA). These data suggest that APC analogs bind predominantly to human serum albumin, but may incorporate into lipoproteins as well.

Figure 2.

Partitioning of alkylphosphocholine analogs to plasma proteins. A) Ultracentrifugation of 1502 reveals binding predominantly to lipoproteins and protein in human plasma. B) Native gel electrophoresis reveals 1502 binding predominantly to albumin in human plasma. C) Equilibrium dialysis reveals that NM404 is highly bound (96%) to human serum albumin. D) Partitioning of APC analogs to lipoproteins and proteins using native gel electrophoresis.

Native gel analysis was performed on all three APC analogs (Figure 2D). Quantification of fluorescence (1501 and 1502) and radioactivity (NM404) revealed significant differences in partitioning between 1502 and the other two analogs. Significantly more LDL and HDL binding was observed with 1502 compared to the other two analogs (Table 1). Furthermore, albumin binding was significantly lower in 1502 (69.88%) compared to NM404 (79.99%, p=0.01) and 1501 (82.64%, p=0.03).

Table 1.

Native Gel Electrophoresis of APC analogs in Human Plasma. Quantitation of fluorescence (1501 and 1502) and radioactivity (NM404) signals in bands corresponding to HDL, LDL and albumin on native gel. Data reported as means ± SEM

| APC Analog | HDL | LDL | Albumin |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM404 | 15.42 ± 0.41 | 4.60 ± 0.28 | 79.99 ± 0.22 |

| 1501 | 10.25 ± 1.25 | 7.11 ± 0.41 | 82.64 ± 1.62 |

| 1502 | 20.90 ± 2.57 | 9.21 ± 0.86 | 69.88 ± 3.32 |

In order to assess the effect of the increasing lipoprotein concentration on partitioning, fresh unfrozen plasma was incubated with APC analogs and different concentrations of intralipid. Intralipid is a FDA approved essential fat formulation composed of 20% soybean oil, 1.2% egg yolk phospholipids, 2.25% glycerin, and water. The main fat constituents are linoleic acid (44–62%), oleic acid (19–30%), palmitic acid (7–14%), α-linolenic acid (4–11%) and stearic acid (1.4–5.5%). Due to its safety and chylomicron-like constitution, intralipid was used to determine the effect of chylomicron or lipoprotein rich plasma on partitioning of APC analogs. Preliminary experiments with NM404, 1501 and 1502 and intralipid demonstrated increased partitioning of the APC analogs to the lipoprotein fraction when these compounds were incubated in fresh unfrozen human plasma in the presence of increasing intralipid concentrations of 0%, and 20% vol/vol (v/v). For 1501, the lipoprotein percentage of fluorescence intensity (measured in the units of radiance efficiency) increased from 7.33% with no intralipid to 14.40% with 20% v/v intralipid (Supplemental Figure S1). Concomitantly, the albumin-binding percentage decreased from 85.93% with no intralipid to 79.32% with 20% intralipid added.

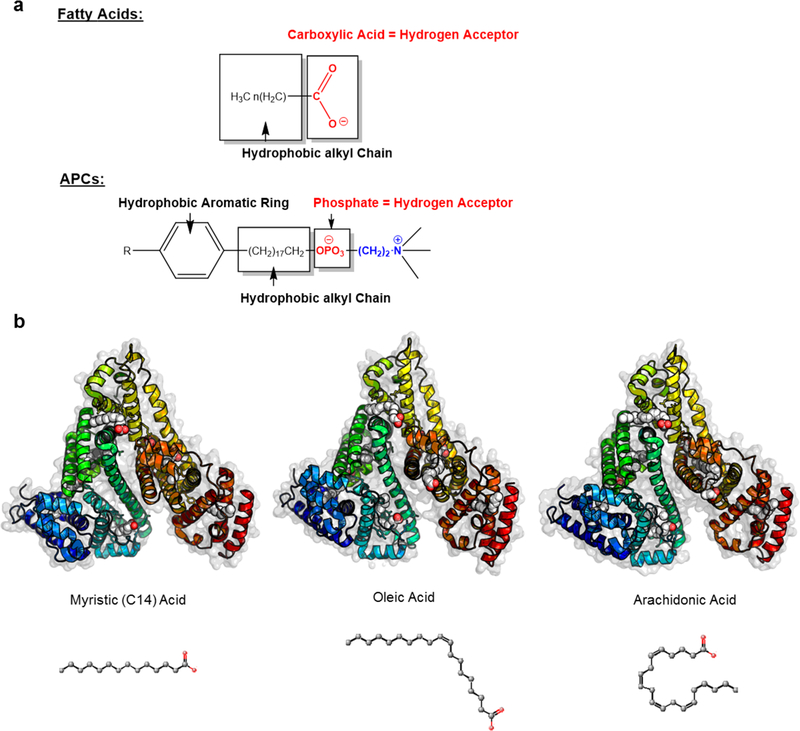

In silico docking analysis reveals APC analogs bind to same seven fatty acid binding sites corroborated by albumin spectrofluorescence assays

APCs and fatty acids share striking structural similarities, which include a polar head group, and hydrophobic alkyl chain (Figure 3A). Crystal structures of long chain fatty acids show binding primarily to seven distinct sites on human serum albumin (Figure 3B)30. Moreover, binding of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are well conserved to these seven binding sites (Figure 3A and Supplemental Videos V1).

Figure 3.

Structural analysis of fatty acids and alkylphosphocholine analogs reveal similarities. A) Alkylphosphocholines and fatty acids bear striking similarities in chemical structure. B) Crystal structure analysis reveals well-conserved binding sites for fatty acids to human serum albumin despite variations in chemical structures between different classes of fatty acids. Long-chain fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids bind to 7 specific sites on human serum albumin.

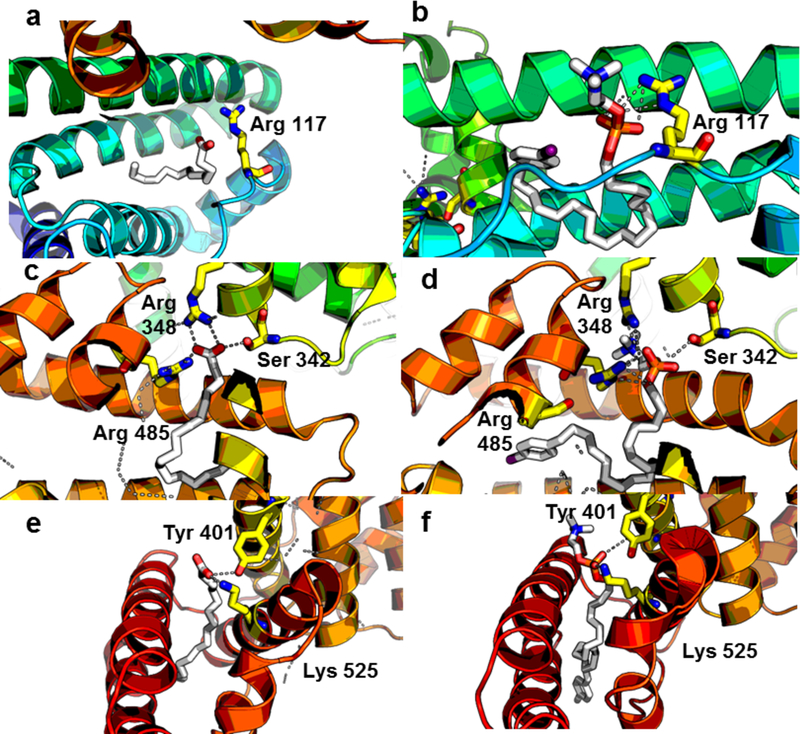

In order to test our hypothesis that FAs and APCs share the same bindings sites on HAS, NM404 was first globally docked nto human serum albumin in the absence of fatty acids to determine the most favorable binding pockets. Global docking analysis revealed binding of NM404 to the seven distinct binding pockets of human serum albumin (Figure 4B). Furthermore, the most favorable docking orientations in these different pockets were conserved between APCs and crystal structure binding of FAs to these pockets (Figure 5). The carboxylic oxygen group of fatty acids coordinate to the basic residues on the protein surface similar to coordination of the phosphate group on NM404 with the same basic residues on albumin.

Figure 4.

In silico docking shows shared binding sites and similar orientation of binding between fatty acids and APC analogs. A) Crystal structure shows 7 high affinity sites of fatty acid binding to human serum albumin. B) in silico docking of NM404 shares same 7 high-affinity docking sites as fatty acids. (C-D) Stearic Acid shares similar docking orientation as NM404 in numerous fatty acid pockets, including fatty acid site 3. (E-F) 1502 docks in reverse orientation due to steric bulk of functional moiety such that zwitterionic phosphocholine is buried in hydrophobic pocket, creating very unfavorable interactions.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure comparison of stearic acid in (A) FA1, (C) FA3, and (E) FA5 and highest affinity in silico docking states of NM404 (B,D,F). The same basic residues coordinate the high-affinity binding of the two compounds. Sites 6 and 7 do not have an orientation of binding.

To corroborate these findings, albumin spectrofluorescence assays were performed to determine shared binding sites. Briefly, tyrosine and tryptophan residues which are enriched in the fatty acid binding pockets of human serum albumin can be excited and emit a natural fluorescence, which is quenched by close ligand contact26. The tryptophan and tyrosine residues exhibited peak excitation at 280nm, and the tyrosine residues exhibited another peak excitation at 295nm (Supplemental figure S2). Emission was measured at 339nm. Some of these residues are found within the fatty acid binding pockets of the protein. In the presence of myristic acid (C14 fatty acid), a significant decrease in quenching was observed upon addition of different molar equivalents of NM404 (Supplemental figure S2). These differences were significant even at 10 molar equivalents of NM404, suggesting that these high-affinity FA pockets were occupied. Moreover, the kinetics of binding are very fast, since quenching was observed immediately after injection and remained stable for 2hr (data not shown). Taken together, these studies suggest that fatty acids and APC analogs share the same binding pockets and orientations.

Different Functional Moieties Impact Albumin Binding and Inform Biological Residence Times of APC analogs

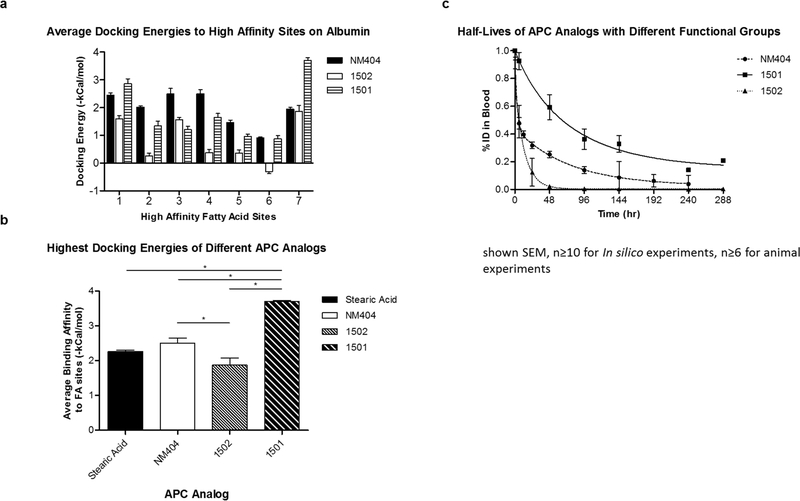

Using in silico docking, we analyzed the binding of stearic acid (C18 fatty acid), 1501, 1502, and NM404 to the seven distinct fatty acid pockets on HSA (Figure 4). Our results show similar docking energies between 1501 and NM404, but not 1502 (Figure 6A). The bulkiness of the near-infrared fluorescence moiety of 1502 reverses many of the docking orientations, namely FA sites 2, 4, and 5 (Figure 4E, 4F, Supplemental video V3), such that the zwitterionic phosphocholine of 1502 is buried into the hydrophobic pocket of these binding sites, creating unfavorable electrostatic interactions. 1502 exhibited significantly lower docking energies for all except fatty acid site 7 compared to NM404 (Figure 6A). Many of these energies were close to 0 kcal/mol suggesting nonspecific binding at these sites. The sites of highest docking energies for NM404 (−2.50±0.15 kcal/mol), 1501 (−1.87±0.21 kcal/mol), and 1502 (−3.70±0.04 kcal/mol) were FA5, FA7, and FA7 respectively. The APCs with the bulkier functional groups, 1501 and 1502 exhibit the highest docking energies to FA7, which is the largest of the FA binding pockets. The highest docking energies between all three compounds were statistically significant using pairwise t-Test. The highest docking energy for 1502 to the other binding sites were significantly lower compared to NM404 (p<10−4), and 1501 (p<10−5) using a pairwise t-Test.

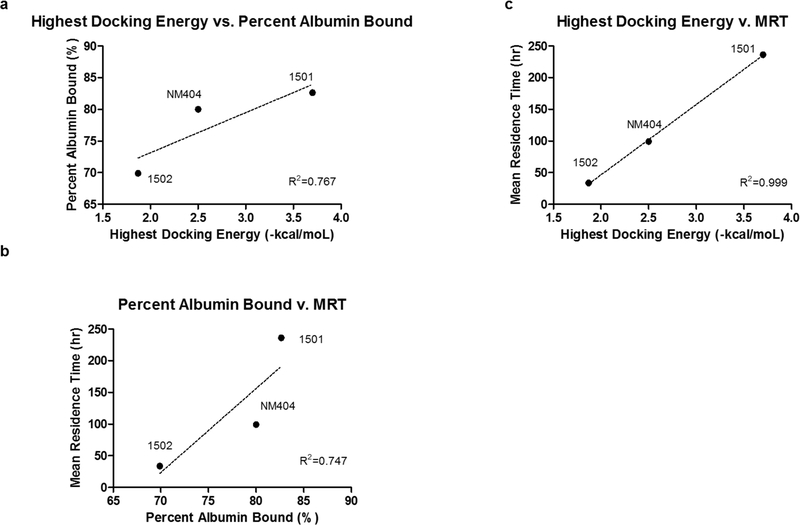

Figure 6.

In silico docking energies correlate with in vivo distribution residence times of APC analogs of different functional moieites. A) Binding energies of stearic acid and different APC analogs of all 7 binding sites. B) Average energies of all 7 sites of stearic acid and APC analogs. C) Mean residence times were determined via blood draws in naive nude athymic mice.

To assess if these docking energies may impact drug clearance, we assessed the residence times of these compounds in nude, athymic mice by collecting small amounts of blood (10μL) through maxillary punctures and plotting blood concentration over time (n=6). Non-compartmental modeling was employed and calculations were normalized to the starting dose. 1502 demonstrated significantly shorter mean residence time (MRT) of 33.95 hr compared to 99.25 hr for NM404, and 236.07 hr for 1501 (Table 2). Clearance values were highest for 1502 (0.08 hr−1) compared to NM404 (0.02 hr−1) and 1501 (0.01 hr−1) as well (Table 2). Area under the curve (AUC) and area under the first moment curve were also calculated for these APC analogs (Table 2).Interestingly, the average logD values and standard error of the three compounds were measured and determined to be 2.07±0.006, 4.59±0.11, and 4.66±0.54 for NM404, 1501, and 1502, respectively. As 1502 is the most lipophilic based on these measurements, consideration of only the lipophilicity property may not best predict albumin binding (Table 2). Regression analysis of the highest docking energy vs. percent albumin binding revealed a R2 value of 0.767; regression analysis of MRT vs. highest docking energy yielded a R2 value of 0.767; regression analysis of percent albumin binding vs. MRT yielded a R2 value of 0.747 (Figure 7B); furthermore, regression analysis of highest docking energy vs. MRT yielded a R2 value of 0.999 (Figure 7C). The highest docking energy was used in the analysis instead of the average docking energy for each compound because the concentration of the APC analogs was significantly less than the concentration of albumin in mice. Regression analysis of logD vs. MRT revealed a poor a poor correlation of R2 value of 0.031. LogD did, however, correlate well with LDL binding.

Table 2.

Non-compartmental Modeling reveals faster clearance and shorter mean residence time for 1502. Non-compartmental analyses was performed on mouse plasma data of the APC analogs.

| Compound | AUC (hr) | AUMC (hr2) | MRT (hr) | CL (L/hr) | log D | Highest Docking Energy (-kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM404 | 43.66 | 4333.63 | 99.25 | 0.02 | 2.07 | 2.50 |

| 1502 | 13.16 | 446.66 | 33.95 | 0.08 | 4.66 | 1.85 |

| 1501 | 159.64 | 37686.99 | 236.07 | 0.01 | 4.59 | 3.70 |

Figure 7.

Regression analysis of A) Highest Docking Energy (-kcal/mol) vs. Percent Albumin Bound (%) with R2 of 0.767, B) Percent Albumin bound (%) vs. Mean Residence Time (hr) with R2 of 0.747, and C) Highest Docking Energy (-kcal/mol) vs. Mean Residence Time (hr) with R2 of 0.999.

1502 Demonstrates Faster Tumor Uptake Kinetics in Mouse Model of Human Breast Cancer

Because 1502 demonstrated the fastest rate of clearance and lowest binding to albumin, we hypothesized that we would achieve the fastest rate of uptake into tumors as well. We compared the flurosecent APC analog 1502 tumor uptake kinetics in tumor-bearing flank xenografts with that of 124I-NM404. Three tumor-bearing mice harboring MDA-MB-231 breast cancer were injected with 1502 and imaged using IVIS fluorescence camera. Uptake into the cancer was seen as early as 4.5 hours, and peaked at 24 hours (Supplemental Figure S3). In contrast, 124I-NM404 demonstrated slower tumor uptake kinetics as previously reported47. With 124I-NM404 tumor uptake was seen at 24 hours and peaked at 72 hours post-injection.

Discussion

APC analogs are versatile delivery agents that can be purposed for multi-modality imaging and therapy. Many of these agents are undergoing evaluation in clinical trials or nearing clinical trials. The long plasma residence times of these synthetic APC analogs and similar compounds may have diagnostic imaging and therapeutic implications. Long delays between administration and imaging that achieves sufficient contrast may decrease the utility of imaging agents, and long distribution kinetics may result in off-target toxicities for therapeutic agents. Therefore, an understanding of the relationship between drug structure and pharmacokinetic properties of these agents can be leveraged to determine feasible strategies for optimizing drug design towards faster tumor uptake and clearance from the body.

Due to the structural similarities between fatty acids and APC analogs, an interrogation of plasma protein binding and partitioning may reveal important pharmacokinetic parameters which may be useful for future drug design or strategies to alter the pharmacokinetics. FAs bear striking resemblance to APCs structurally, as both share a polar head group and long hydrophobic tail15. In silico binding studies and partitioning studies reveal similar binding characteristics between these two distinct classes of compounds15. Namely, the same binding pockets for FAs on albumin are also favorable sites of binding for APC analogs. Also, as chain length increases for FAs, there appears to be less binding to albumin sites and more partitioning to the lipoprotein fraction36–37. Our results suggest that the same is seen with increasing size of APC analogs. Addition of bulkier diapeutic moieties impairs 1502 binding to albumin, increasing its partitioning onto lipoproteins. Moreover, the bulkier analogs 1501 and 1502 preferentially bind to the largest FA binding site FA7, analogous to very long chain fatty acids. Our analysis of the docking energies and MRT demonstrate a significant positive correlation between the highest docking energies of the APC analogs and their MRTs (R2 = 0.999).

Importantly, the albumin docking energies correlated inversely with the tumor uptake kinetics in tumor-bearing mice. 1502 demonstrated significantly faster uptake into tumors compared to 124I-NM404. Our in silico modeling has helped in not only yielding important predictive information about APC analogs pharmacokinetics, but has also helped in optimizing the PK our next generation of fluorescent APC analogs. Our modeling approach represents an economical and powerful approach that may circumvent the expensive and time-consuming synthesis and in vivo pharmacokinetic testing. Designing APC analogs with faster pharmacokinetics will ultimately translate into faster imaging agents and safer therapy agents for cancer. Because many lipophilic compounds also bind to the same sites, the same modeling principles may also produce predictive PK characteristics for other drug classes beside APCs. Further testing with additional APC analogs is underway to determine the robustness of this in silico model, and help guide design of future generation APC analogs with tailored PK profiles48.

Our pharmacokinetics studies also suggest that in silico modeling may be a more sensitive predictor of albumin binding and residence times compared to more crude and non-specific physicochemical measurements such as logD49. Because our in silico methodology specifically interrogates the hydrophobic pockets on albumin, and normalizes binding to the surface of albumin, our methodology is suited to study partitioning. The rationale behind our model is that these APC analogs have a very small unbound fraction, and that lipoproteins scavenge the free APC analogs and the weakly bound drugs at the surface of albumin. In addition, the physiological concentrations of APC compound to albumin is much less than 1:1. The results from the modeling and PK experiments show a significant positive correlation between the highest energy binding and the residence time of the APC analogs.

We also observe the structural effects of the functional moieties on drug partitioning. As the bulkiness of the diapeutic moieties of these APC analogs increases in size, partitioning to the lipoprotein fraction(s) also increase, in agreement with studies performed with fatty acids of increasing alkyl chain lengths35–37. Lipoprotein binding of lipophilic compounds have been well supported in the scientific literature50–53. In vitro studies using intralipid supports the idea that there is a competition of binding of APCs to lipoproteins and albumin. Lipoprotein-bound APC analogs may have faster clearance than the albumin-bound APC analogs, and therefore decrease the residence times of these agents. Lipoproteins have a much faster clearance than albumin, which circulate for about 19 days before being catabolized by the liver54. Lipoprotein-binding drugs such as cyclosporine demonstrate increased bioavailability and faster clearance with high fat diets, suggesting that the lipid profile may modulate clearance of lipoprotein-bound drugs50, 55. These results suggest that increased binding to lipoproteins may increase the clearance rate of these compounds, and that free drug concentrations and hepatic extraction may not have a significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of these APC analogs.

To our knowledge, these studies illustrate the purported binding sites of alkylphosphocholines on human serum albumin. Moreover, we have established structure-binding and structure-partitioning trends that may be used in future drug design of alkylphosphocholines and other classes of small molecules that display structural similarities. This methodology can be immediately applied to FDA approved APL analogs, and other lipophilic compounds.

The expensive and time-consuming process of synthesis and testing of different drug compounds can be minimized if predictive modeling is successfully validated in efforts to effectively screen compounds with the most favorable properties. In cancer drug development, only 5% of preclinical effective drugs make it through FDA approval, and the overwhelming majority fail primarily due to poor pharmacokinetic properties7–9. Therefore, we have developed and corroborated an in silico modeling methodology that predicts pharmacokinetic behavior based on the structure of APC analogs and hydrophobic binding pockets on human serum albumin. Our methodology enables design of future analogs with more tailored pharmacokinetics, and also provides pertinent and comparative insights into behaviors of similar lipophilic compounds. This represents a powerful and economical approach to screen for lead compounds with optimal pharmacokinetics to minimize failure along the drug development pipeline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Cellectar Biosciences Inc (Madison, WI) for providing the APC analogs used in this work.

Funding Sources: RRZ was partially supported by the University of Wisconsin MD PhD program via T32 GM008692. PAC, JSK was supported in part by NIH R01NS75995, Headrush Brain Tumor Research Professorship, and Roger Loff Memorial Fund “Farming against Brain Cancer”. JAL was supported by the Schapiro Research Fund. JPW and JSK were partially supported by NCI R01-15880 grant. Cellectar Biosciences (Madison, WI) provided APC analogs.

ABBREVIATION

- SAPC

alkylphosphocholine

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- HSA

human serum albumin

- PET

positron emission tomography

- APL

alkylphospholipid

- FA

fatty acid

- MRT

mean residence time

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

Footnotes

Competing Interests: Anatoly N Pinchuk, and M. Longino declare associations with the following companies: Cellectar Biosciences Inc. R. R. Zhang, T. I. Mehta, J. Grudzinski, J. Jeffrey, P. A. Clark, R. Burnette, J. A. Lubin, M. Longino,J. S. Kuo, J. P. Weichert declare no competing interests.

Supporting Information:

Supporting information contains: albumin spectrofluorescence data, lipoprotein partitioning of 1501 and 1502 with the addition of intralipid, fluorescence imaging of the tumor uptake in MDA-MB-231 flank xenografts injected with 1502, and docking videos of NM404 and 1502 binding to the fatty acid pockets on human serum albumin.

References

- 1.Benet LZ; Kroetz D; Sheiner L; Hardman J; Limbird L, Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics 1996, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohnert T; Gan LS, Plasma protein binding: from discovery to development. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2013, 102 (9), 2953–2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabbani G; Ahn SN, Structure, enzymatic activities, glycation and therapeutic potential of human serum albumin: A natural cargo. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knox SJ; Goris ML; Trisler K; Negrin R; Davis T; Liles T-M; Grillo-Lopez A; Chinn P; Varns C; Ning S-C, Yttrium-90-labeled anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy of recurrent B-cell lymphoma. Clinical Cancer Research 1996, 2 (3), 457–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminski MS; Zasadny KR; Francis IR; Milik AW; Ross CW; Moon SD; Crawford SM; Burgess JM; Petry NA; Butchko GM, Radioimmunotherapy of B-cell lymphoma with [131I] anti-B1 (anti-CD20) antibody. New England Journal of Medicine 1993, 329 (7), 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane D; Eagle K; Begent R; Hope-Stone L; Green A; Casey J; Keep P; Kelly A; Ledermann J; Glaser M, Radioimmunotherapy of metastatic colorectal tumours with iodine-131-labelled antibody to carcinoembryonic antigen: phase I/II study with comparative biodistribution of intact and F (ab’) 2 antibodies. British journal of cancer 1994, 70 (3), 521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner M; Neri D, Antibody-radionuclide conjugates for cancer therapy: historical considerations and new trends. Clinical Cancer Research 2011, 17 (20), 6406–6416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchinson L; Kirk R, High drug attrition rates—where are we going wrong? Nature Publishing Group: 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy T, Managing the drug discovery/development interface. Drug discovery today 1997, 2 (10), 436–444. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van De Waterbeemd H; Gifford E, ADMET in silico modelling: towards prediction paradise? Nature reviews Drug discovery 2003, 2 (3), 192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitchen DB; Decornez H; Furr JR; Bajorath J, Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004, 3 (11), 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colmenarejo G, In silico prediction of drug-binding strengths to human serum albumin. Medicinal research reviews 2003, 23 (3), 275–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabbani G; Baig MH; Lee EJ; Cho W-K; Ma JY; Choi I, Biophysical study on the interaction between eperisone hydrochloride and human serum albumin using spectroscopic, calorimetric, and molecular docking analyses. Molecular pharmaceutics 2017, 14 (5), 1656–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabbani G; Lee EJ; Ahmad K; Baig MH; Choi I, Binding of tolperisone hydrochloride with human serum albumin: effects on the conformation, thermodynamics, and activity of HSA. Molecular pharmaceutics 2018, 15 (4), 1445–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabbani G; Baig MH; Jan AT; Lee EJ; Khan MV; Zaman M; Farouk A-E; Khan RH; Choi I, Binding of erucic acid with human serum albumin using a spectroscopic and molecular docking study. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 105, 1572–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karthikeyan S; Bharanidharan G; Raghavan S; Kandasamy S; Chinnathambi S; Udayakumar K; Mangaiyarkarasi R; Suganya R; Aruna P; Ganesan S, Exploring the binding interaction mechanism of taxol in β–tubulin and bovine serum albumin: A biophysical approach. Molecular pharmaceutics 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinchuk AN; Rampy MA; Longino MA; Skinner RWS; Gross MD; Weichert JP; Counsell RE, Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationship Effects on the Tumor Avidity of Radioiodinated Phospholipid Ether Analogues. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 49 (7), 2155–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weichert JP; Clark PA; Kandela IK; Vaccaro AM; Clarke W; Longino MA; Pinchuk AN; Farhoud M; Swanson KI; Floberg JM; Grudzinski J; Titz B; Traynor AM; Chen H-E; Hall LT; Pazoles CJ; Pickhardt PJ; Kuo JS, Alkylphosphocholine Analogs for Broad-Spectrum Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6 (240), 240ra75–240ra75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang RR; Schroeder AB; Grudzinski JJ; Rosenthal EL; Warram JM; Pinchuk AN; Eliceiri KW; Kuo JS; Weichert JP, Beyond the margins: real-time detection of cancer using targeted fluorophores. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson KI; Clark PA; Zhang RR; Kandela IK; Farhoud M; Weichert JP; Kuo JS, Fluorescent Cancer-Selective Alkylphosphocholine Analogs for Intraoperative Glioma Detection. Neurosurgery 2015, 76 (2), 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grudzinski JJ; Titz B; Kozak K; Clarke W; Allen E; Trembath L; Stabin M; Marshall J; Cho SY; Wong TZ; Mortimer J; Weichert JP, A Phase 1 Study of 131I-CLR1404 in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Tumors: Dosimetry, Biodistribution, Pharmacokinetics, and Safety. PLoS ONE 2014, 9 (11), e111652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korb ML; Warram JM; Grudzinski J; Weichert J; Jeffery J; Rosenthal EL, Breast Cancer Imaging Using the Near-Infrared Fluorescent Agent, CLR1502. Molecular imaging 2014, 13, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubner SJ; Mullvain J; Perlman S; Pishvaian M; Mortimer J; Oliver K; Heideman J; Hall L; Weichert J; Liu G, A Phase 1, Multi-Center, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Study of 131I-CLR1404 in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Malignancies. Cancer investigation 2015, 33 (10), 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deming DA; Maher ME; Leystra AA; Grudzinski JP; Clipson L; Albrecht DM; Washington MK; Matkowskyj KA; Hall LT; Lubner SJ, Phospholipid ether analogs for the detection of colorectal tumors. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang RR; Swanson KI; Hall LT; Weichert JP; Kuo JS, Diapeutic cancer-targeting alkylphosphocholine analogs may advance management of brain malignancies. CNS oncology 2016, 5 (4), 223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo S; Shi X; Yang F; Chen L; Meehan, Edward J.; Bian, C.; Huang, M., Structural basis of transport of lysophospholipids by human serum albumin. Biochemical Journal 2009, 423 (1), 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley EE; Modest EJ; Burns CP, Unidirectional membrane uptake of the ether lipid antineoplastic agent edelfosine by L1210 cells. Biochemical Pharmacology 1993, 45 (12), 2435–2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang H; Cannon MJ; Banach M; Pinchuk AN; Ton GN; Scheuerell C; Longino MA; Weichert JP; Tollefson R; Clarke WR, Quantification of CLR1401, a novel alkylphosphocholine anticancer agent, in rat plasma by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometric detection. Journal of Chromatography B 2010, 878 (19), 1513–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashbrook JD; Spector AA; Santos EC; Fletcher JE, Long chain fatty acid binding to human plasma albumin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1975, 250 (6), 2333–2338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattacharya AA; Grüne T; Curry S, Crystallographic analysis reveals common modes of binding of medium and long-chain fatty acids to human serum albumin1. Journal of Molecular Biology 2000, 303 (5), 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curry S; Brick P; Franks NP, Fatty acid binding to human serum albumin: new insights from crystallographic studies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1999, 1441 (2–3), 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curry S; Mandelkow H; Brick P; Franks N, Crystal structure of human serum albumin complexed with fatty acid reveals an asymmetric distribution of binding sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol 1998, 5 (9), 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He XM; Carter DC, Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature 1992, 358 (6383), 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petitpas I; Grüne T; Bhattacharya AA; Curry S, Crystal structures of human serum albumin complexed with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids1. Journal of Molecular Biology 2001, 314 (5), 955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richieri GV; Anel A; Kleinfeld AM, Interactions of long-chain fatty acids and albumin: Determination of free fatty acid levels using the fluorescent probe ADIFAB. Biochemistry 1993, 32 (29), 7574–7580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J-K; Ho J; Curry S; Qin D; Bittman R; Hamilton JA, Interactions of very long-chain saturated fatty acids with serum albumin. Journal of Lipid Research 2002, 43 (7), 1000–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho JK; Moser H; Kishimoto Y; Hamilton JA, Interactions of a very long chain fatty acid with model membranes and serum albumin. Implications for the pathogenesis of adrenoleukodystrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1995, 96 (3), 1455–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weichert JP; Van Dort ME; Groziak MP; Counsell RE, Radioiodination via isotope exchange in pivalic acid. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation. Part A. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 1986, 37 (8), 907–913. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barré J; Chamouard JM; Houin G; Tillement JP, Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration, and ultracentrifugation compared for determining the plasma-protein-binding characteristics of valproic acid. Clinical Chemistry 1985, 31 (1), 60–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung BH; Wilkinson T; Geer JC; Segrest JP, Preparative and quantitative isolation of plasma lipoproteins: rapid, single discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation in a vertical rotor. Journal of Lipid Research 1980, 21 (3), 284–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodríguez-Sureda V. c.; Julve J; Llobera M; Peinado-Onsurbe J, Ultracentrifugation Micromethod for Preparation of Small Experimental Animal Lipoproteins. Analytical Biochemistry 2002, 303 (1), 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao H; Lei L; Liu J; Kong Q; Chen X; Hu Z, The study on the interaction between human serum albumin and a new reagent with antitumour activity by spectrophotometric methods. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2004, 167 (2–3), 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waters NJ; Jones R; Williams G; Sohal B, Validation of a rapid equilibrium dialysis approach for the measurement of plasma protein binding. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2008, 97 (10), 4586–4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seeliger D; de Groot B, Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design 2010, 24 (5), 417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trott O; Olson AJ, AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2010, 31 (2), 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swanson KI; Clark PA; Zhang RR; Kandela IK; Farhoud M; Weichert JP; Kuo JS, Fluorescent cancer-selective alkylphosphocholine analogs for intraoperative glioma detection. Neurosurgery 2015, 76 (2), 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grudzinski JJ; Floberg JM; Mudd SR; Jeffery JJ; Peterson ET; Nomura A; Burnette RR; Tomé WA; Weichert JP; Jeraj R, Application of a whole-body pharmacokinetic model for targeted radionuclide therapy to NM404 and FLT. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2012, 57 (6), 1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernandez R; Walker KL; Grudzinski JJ; Aluicio-Sarduy E; Patel R; Zahm CD; Pinchuk AN; Massey CF; Bitton AN; Brown RJ, 90 Y-NM600 targeted radionuclide therapy induces immunologic memory in syngeneic models of T-cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Communications biology 2019, 2 (1), 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van de Waterbeemd H; Smith DA; Jones BC, Lipophilicity in PK design: methyl, ethyl, futile. Journal of computer-aided molecular design 2001, 15 (3), 273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brocks DR; Ala S; Aliabadi HM, The effect of increased lipoprotein levels on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine A in the laboratory rat. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition 2006, 27 (1), 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brocks DR; Wasan KM, The influence of lipids on stereoselective pharmacokinetics of halofantrine: Important implications in food-effect studies involving drugs that bind to lipoproteins. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2002, 91 (8), 1817–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su J; He L; Zhang N; Ho PC, Evaluation of Tributyrin Lipid Emulsion with Affinity to Low-Density Lipoprotein: Pharmacokinetics in Adult Male Wistar Rats and Cellular Activity on Caco-2 and HepG2 Cell Lines. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2006, 316 (1), 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vuong TD; Stroes ESG; Willekes-Koolschijn N; Rabelink TJ; Koomans HA; Joles JA, Hypoalbuminemia increases lysophosphatidylcholine in low-density lipoprotein of normocholesterolemic subjects. Kidney Int 1999, 55 (3), 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sleep D; Cameron J; Evans LR, Albumin as a versatile platform for drug half-life extension. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2013, 1830 (12), 5526–5534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah AK; Sawchuk RJ, Effect of co-administration of intralipidTM on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine in the rabbit. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition 1991, 12 (6), 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.