Abstract

Objectives:

Oncologists can be one of the major barriers to older adult’s participation in research. Multiple studies have described academic clinicians’ concerns for not enrolling older adults onto trials. Although the majority of older adults receive their cancer care in the community, few studies have examined the unique challenges that community oncologists face and how they differ from oncologist-related barriers in academia.

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by telephone or face-to-face with 44 medical oncologists (24 academic-based and 20 community-based) at City of Hope from March to June 2018. Interviews explored oncologists’ perceptions of barriers to clinical trial enrollment of older adults with cancer. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results:

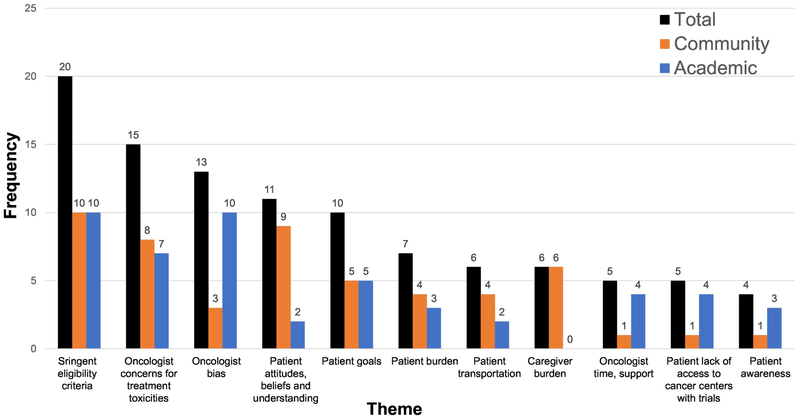

Of the 44 participants, 36% were women and 68% were in practice for >10 years. Among the entire sample, stringent eligibility criteria (n=20) and oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities (n= 15) were the most commonly cited barriers. Compared to academic oncologists, community oncologists more often cited patient attitudes, beliefs, and understanding (n=9 vs. n=2) and caregiver burden (n=6 vs. n=0). In contrast, compared to community oncologists, academic oncologists more often cited oncologist bias (n=10 vs. n=3) and insufficient time/support (n=4 vs. n=1).

Conclusions:

Differences in perceptions among academic and community oncologists about trials suggest that barriers are multifaceted, complex, and vary by practice setting. Interventions to increase trial accrual among older adults with cancer may benefit from being tailored to address the unique barriers of different practice settings.

INTRODUCTION

Although nearly 60% of all cancers in the United States are diagnosed in individuals age ≥ 65, less than 40% of clinical trial participants are age ≥ 65.1 Hence, older adults are vastly underrepresented in clinical trials that set the standard for cancer treatment. Additionally, there has been little increase in the proportion of older adults that participate in oncology clinical trials over time.2 As a result of this persistent problem, oncologists have limited evidence on how best to treat this growing and vulnerable population of patients.3 Efforts to increase clinical trial participation of older adults have been identified as a priority by several national organizations, including the Institute of Medicine,4 the American Society of Clinical Oncology,5-7 and the Cancer and Aging Research Group.8

Reasons for poor representation of older adults in cancer clinical trials are complex and multifaceted. Barriers exist through a combination of oncologist, patient and/or caregiver, and system factors.9-15 In particular, oncologists play a central role in whether a patient is offered and/or considered for a clinical trial.16 To date, quantitative surveys17-21 and retrospective analyses22, 23 have focused on oncologists’ perceptions of the barriers to enrolling older adults with cancer onto clinical trials. Oncologists have reported concerns about increased toxicities, patient ineligibility due to overly stringent criteria, patient age, patient treatment preferences, lack of time, and limited resources and support as barriers to accrual.17-21,24-26 However, most of these studies have focused on academic oncologists’ perspectives, and as a result, there is limited understanding of community oncologists’ perspectives. To date, only one study, to our knowledge, reported perceived barriers to enrollment of older adults with cancer by community providers in a cooperative group meeting, but did not measure or characterize these concerns in any detail.23

Examining the barriers that community oncologists face is important for several reasons. First, studies suggest that nearly 80% of older patients receive their cancer care in the community.27 Second, community-based cancer research (and barriers) might be different than academic-based research. For example, community oncologists tend to care for large patient volumes with a wide variety of cancer subtypes, while academic oncologists often care for fewer patients with one cancer subtype.28,29 Hence, academic oncologists may be more aware of available cancer clinical trials compared to their peers in the community. Additionally, academic physicians may be incentivized to accrue patients onto clinical trials as part of their promotion and job responsibilities.28,30 Finally, community-based cancer practices often lack the infrastructure (e.g., financial and personnel support) to conduct a clinical trial, including assisting oncologists with consenting, screening, and completing study procedures.31,32

Understanding how barriers differ by practice setting is an important step in addressing this persistent challenge in oncology and identifying new solutions. However, to our knowledge, no prior study has simultaneously characterized the perception of barriers faced by academic and community oncologists. Furthermore, most studies exploring this topic have been quantitative surveys and retrospective studies, which are unable to capture important nuances of oncologists’ perceptions of this complex issue. Therefore, the objective of this study was to use a qualitative approach to describe and compare community and academic oncologists’ perceptions of the barriers to clinical trial enrollment of older adults with cancer.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted semi-structured interviews among academic and community medical oncologists at City of Hope (COH) from March to June 2018. We sampled oncologists from one academic, tertiary care center located in Duarte (COH main campus) and six affiliated community practice sites located in Southern California (Mission Hills, South Pasadena, Rancho Cucamonga, Antelope Valley, West Covina, and Colton). COH Institutional Review Board determined this study was exempt.

Interview Guide Development

The initial interview guide was developed based on a prior framework, which the study team developed following a literature review10,33-38 examining studies that investigated the barriers to clinical trial accrual in the geriatric oncology population. This framework underscores that the barriers are multifaceted and often a combination of system-,17,21,23,39-42 physician,17,18,21,23,39,41-44 patient-,17,18,23,40-47 and caregiver-related17,21,41,43 factors. Questions explored oncologists’ perceptions of the barriers to clinical trial enrollment among older adults with cancer and included prompts to elicit reasons for these barriers. The interview guide was refined through iterative review by a qualitative researcher (VS), a geriatric oncologist (MS), and a trained clinical research coordinator (KG).

A pilot interview with an oncologist was recorded and transcribed prior to commencement of the study to ensure the format and structure of the interview was appropriate. Based on feedback, minor changes in the interview guide were made for improved clarity of the questions. The pilot interview was not included in the final analysis. The interview guide included prompts (see Supplemental 1. Interview Guide).

Participant Recruitment

We recruited participants from COH main campus (academic center) and six additional, COH-affiliated community sites. The purpose of this sampling strategy was to capture a range of oncologists’ perspectives across both academic and community practice settings. Oncologists were invited via email to participate in telephone or face-to-face interviews. Twenty-four academic oncologists and 23 community oncologists were initially approached to participate in this study. Among the total 47 approached, 44 medical oncologists (24 [100%] from academia and 20 [87%] from community sites) agreed to participate and completed the interview. One participant declined due to the lack of availability to complete the interview; two people did not respond to the email invitation.

Data Collection

Semi-structured one-on-one interview were conducted with all participants individually. Twenty-four face-to-face interviews were conducted in private rooms (e.g., physician offices); 20 interviews were completed over the phone per participant request. All interviews were conducted by a trained clinical research coordinator (KG, a male post-graduate student, with two years of clinical research experience in oncology and structured training in qualitative interviewing).

Participants were informed of the basis of the research and were given a written “Statement of Research” explaining the purpose of the study prior to commencement. Participants were unknown to the interviewer and interviewed once. Flexible use of the interview guide was employed to allow participants’ perspectives to be explored in depth. No other persons were present during the interview. Field notes were made during and/or following the interviews, which ranged from 10 to 48 minutes (M = 22 minutes, SD = 7 minutes).

All interviews were audio-recorded using a digital recorder. KG and AW transcribed interviews verbatim and transcripts were reviewed for quality control by two additional clinical research coordinators (AW and SP). No transcripts were returned to participants for feedback.

Data Analysis

Data were managed using qualitative analysis software (QSR International’s NVivo v12). Two analysts (KG, AW) independently coded interviews using thematic content analysis.48,49 Specifically, an inductive approach was taken, where themes were derived from the content of text data and did not involve a predetermined theory or framework. Based on the prior literature,49-52 we adapted a two-step approach to generate themes.

First, KG and AW developed a preliminary codebook after reviewing 10 transcripts. To test the credibility of the preliminary codebook, KG and AW coded the remaining 34 interviews independently. To assess inter-rater reliability (IRR), Cohen’s kappa was calculated for each theme (average kappa = 0.88). The IRR scores were included to confirm that the coding frame was good and that the codes from the two independent investigators were objective and reliable indicators of the qualitative text content.

Second, themes were finalized through further iterative refinement of the codebook. Discussions and refinements were informed by calculated kappa values; all themes with a kappa below 0.7 were refined. Any remaining discordant coding was discussed and adjudicated for final consensus with two additional study investigators (MS, VS). All transcripts were recoded as codebooks were refined. Themes identified and the number of oncologists that reported each theme was recorded. Findings were reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).53

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

In total, 44 medical oncologists participated in qualitative interviews: 24/24 (100%) of COH academic oncologists and 20/23 (87%) of COH community oncologists (Table 1). Of the 44 participants, 16 were women (12 academic oncologists, 4 community oncologists) and 30 had over 10 years of experience in practice (17 academic oncologists, 13 community oncologists).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Academic (n=24) No. (%) |

Community (n=20) No. (%) |

Total (n=44) No. (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No. women | 12 (50) | 4 (20) | 16 (36) |

| Years in practice | |||

| <5 | 2 (8) | 4 (20) | 6 (14) |

| 5-10 | 5 (21) | 3 (15) | 8 (18) |

| >10 | 17 (71) | 13 (65) | 30 (68) |

| No. patients in practice | |||

| <500 | 17 (71) | 8 (40) | 25 (57) |

| 500-1000 | 6 (25) | 8 (40) | 14 (32) |

| 1000 | 1 (4) | 4 (20) | 5 (11) |

| % of patients enrolled on clinical trials | |||

| <5 | 13 (54) | 16 (80) | 29 (66) |

| 5-10 | 9 (38) | 3 (15) | 12 (27) |

| >10 | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) |

A greater proportion of community oncologists (20%, n=4) reported caring for >1000 outpatients a year compared to academic oncologists (4%, n=1). In contrast, a greater proportion of academic oncologists (46%, n= 11) reported having greater than 5% of their patients enrolled on clinical trials compared to community oncologists (20%, n=4).

Identified Themes

Among the entire sample (academic and community oncologists), 11 distinct themes were identified. Oncologists most commonly reported two themes: “stringent eligibility criteria” and “oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities” as barriers for older adult inclusion in cancer clinical trials. Additionally, the remaining nine themes identified included: “oncologist bias;” “patient attitudes, beliefs, and understanding;” “patient goals;” “patient burden;” “patient transportation;” “caregiver burden;” “oncologist time, support;” “patient lack of access to cancer centers with trials;” and “patient awareness.” Each of these themes, along with exemplary responses, are summarized in Table 2. Additionally, we have included the frequencies of responses among the entire sample and the academic/community oncologist cohorts (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Oncologists’ perceptions of barriers to older adults in oncology clinical trials: identified themes, representatives quotes, and frequencies (N)

| Themes | Representative Quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Oncologist | Community Oncologist | |

| Stringent eligibility criteria | Potentially minor comorbidities may become a little more pronounced in an older adult and they become less likely to even become eligible for the trials that are out there. [P13] Many of the clinical [trials have] stringent eligibility criteria. For example, I saw a patient who would be a clinical trial candidate, but the study exclude[d] anybody who had [a second,] even curable, malignancy within the last 5 years. [P16] [Regarding] performance status, I think the elderly … are not [functionally] well [compared to younger adults]. That's why we may exclude [the elderly]… [they] have to meet the [stringent eligibility] criteria. [P17] Well, patients might have multiple medical problems as they age, and therefore some of the eligibility criteria might be too restrictive. [P25] |

The entry criteria for patients is very narrow and therefore [if] patients have comorbidities when they are over 65, [these stringent criteria] prevents us from accruing them to trials. [P26] We know that older adults have a whole host of medical issues that make them sometimes ineligible [to participate in a clinical trial]. [P27] Some of the trials are very stringent and difficult to conduct in older people. [P28] Some trials have age limits that particularly say you can't have a patient over a certain age. [P30] [Studies] want patients who have little or no comorbidity, and excellent physical shape, and good performance status. [P37] Typically, the performance status declines after 65 and so that ends up being one of the main reasons. [P44] |

| Oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities | There are some older adults who I think don't accrue to clinical trials because they are frail [P2] [Physicians] might think [older adults] are potentially too frail to tolerate therapy … [Physicians] certainly don't want to hurt [older adults] with an investigational treatment. [P18] |

I think there is a bit more hand holding that we need to do, possibly more side-effects that could … happen that you have to address. [P27] They have other medical problems; they are taking other medications and it becomes difficult… the extra blood draws and the extra biopsies make it difficult for them. [P28] |

| Oncologist bias | Providers just don't offer people clinical trials, particularly older individuals, just because of their age. [P2] [Physicians] are a little bit ageist and will often times just rule people out because of [age]. I think [physicians] will automatically read a chart and say, gosh, this person is 88, there's no way they'll ever be able to participate. [P4] I think there is age bias. I think doctors generally don't think of [offering a clinical trial] in people who are over say, 80. I think there's less age bias in the 60-year-old age group. [P10] |

There is inherent bias … about enrolling older people. [P27] Sometimes the physician knows that putting them on a clinical trial is not beneficial, considering their age, like 80 years old and 90 … a clinical trial is too much for the patient. [P37] |

| Patient attitudes, beliefs and understanding | There is a higher likelihood that an [older] patient [does] not want to be a “guinea pig” on a clinical trial. [P25] | Patients over 65 are somewhat more afraid of participating in trials. [P26] Older patients might not be so willing to participate in what they perceive to be experimental and potentially harmful, so sometimes that discussion with someone that is a lot older might not even happen. [P29] [Older patients] might not necessarily want to do something "experimental”. [P33] When you talk about experimental treatment, [older patients] think that… they are experimenting on me. [P42] |

| Patient goals | I think … with some older patients … they had a great life and they had a long life … and they really wanted to emphasize sort of time with their family, and so the schedules and being in and out of the hospital … were less desirable. [P2] Older adults are just not that interested in having their quality of life messed with. [P24] |

Older patients might be more prone to accept the terminal nature of their illness. [P29] It is amazing when you talk to people in their 70’s and 80’s and really learn … many of them will look you in the eye and they kind of know that they are what I call “on the edge” I don’t have a better explanation for it than that. They kind of know any other thing is going to tip over their life and it won’t be good quality. And they are kind of pulling it all together right now, and so just going through treatment alone. They may or may not want to do that. And let alone an investigational trial where sometimes it sounds like the side effects could be much worse, that is a really hard choice. [P39] |

| Patient burden | [The patient will] say “I really don’t want to spend that much time here in the hospital.” [P6] People don't want to [come to clinic frequently]. They don't want to travel to see a [specialist] when they are a community [doctor] nearby. [P14] |

An older patient, even if it is a retired patient who is not working… you might assume that person has a lot more time to participate in a clinical trial and go to extra visits, [however] sometimes I get the feeling they're actually the one's reluctant to put in the extra effort that might be necessary for a clinical trial. [P33] A patient, especially when they are older … get impatient. They don't want to wait around to get screened, they just go to get treated so sometimes we just say forget it we will treat you without waiting around to see if they can screen. [P35] |

| Patient transportation | [Older patients] have trouble getting back and forth to clinic. [P2] [It is difficult for] for a 90-year-old who is staying with his kids who cannot drive who lives an hour and a half from here and he has to go on a clinical trial that requires evaluation three times a week. [P15] |

Because older adults sometimes can't drive, sometimes they don't have transportation. [P27] It is transportation, [patients] are driving back and forth and they feel like "okay, not fair.” [P28] Some of the barriers might be the distance the patient may have to travel. [P33] |

| Caregiver burden | None noted | Sometimes [patients] can't really take care of themselves at home, and needs help. And for the caretaker to see all the regimented protocol, bring them in on a certain time, or additional testing that may be done is more of a hardship on them. [P27] The family sometimes doesn't want it. We do [try to] get them to understand that this is not experimental medicine, and [that] we are trying to get good care, but sometimes it is difficult for the families to comprehend that. [P28] [Sometimes] the patient and the family do not want to bother. [P31] It would be more difficult for an older patient who may have to rely on some family member. [P38] Usually it is family issues … the family [are] reluctant for a [patient to enroll in] a clinical trial. [P40] |

| Oncologist time, support | Older patients [have]…more medications [and] co-morbid conditions. To take an extra hour every single day, to make sure [older adults] fit the eligibility criteria, would be a challenge. [P6] You've got 25 minutes at most to deal with the patient. If you're going to start trying to convince older adults… it’s all a matter of time, we don’t have the time. [P24] |

In a busy practice, where you see patients every 15 or every 20 minutes, the need to kind of stay on schedule, so that you're not delayed with your schedule, so that patients are not upset about late appointments, I think there's the temptation to just continue the standard treatment rather than exploring clinical trial options. [P33] |

| Patient lack of access to cancer centers with trials | The biggest barrier, national-wise, or endemic-wise, is older people don't have resources, knowledge, or man power to bring them to tertiary centers. [P12] | Traditionally it was because there were no trials available locally. [P38] |

| Patient awareness | Sometimes [patients] don’t even know [about clinical trials], unless they have an advocate at home or family member who is a physician. [P12] [Patients] might just not know that studi[es are] open. [P23] |

Education [is a barrier], just keeping the patients up to date about the options that are available. [P36] |

Fig. 1.

Oncologist-identified barriers to enrollment among older adults.

Common Themes Across Sites

Of the 11 themes, stringent eligibility criteria and oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities were two commonly identified themes by both academic and community oncologists. Both themes emerged as key barriers across both practice settings.

Eligibility Criteria.

Both academic and community oncologists most frequently cited stringent eligibility criteria as a barrier. For example, an academic oncologist noted the difficulty of enrolling older adults onto clinical trials because trial eligibility criteria often exclude patients with comorbidities:

“Potentially minor comorbidities may become a little more pronounced in an older adult and they become less likely to even become eligible for the trials that are out there.” [P13]

Similarly, a community oncologist expressed that older adult’s chronic medical conditions make them ineligible for trial participation:

“Older adults have a whole host of medical issues [comorbidities] that make them sometimes ineligible.” [P27]

Toxicity Concerns.

Academic and community oncologists also frequently cited oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities as a barrier to enrollment. For instance, an academic oncologist expressed concern for offering clinical trials to older patients due to the potential risk for adverse side effects:

“[Physicians] might think [older adults] are potentially too frail to tolerate therapy … [Physicians] certainly don't want to hurt [older adults] with an investigational treatment.” [P18]

Likewise, a community oncologist noted that the potential for toxicities to occur in frailer older patients may deter consideration of a clinical trial:

“When you have an older patient who is typically frail my first thought is how to best palliate the rest of their life, I'm not convinced that enrolling a patient in novel trials is going to palliate them well.” [P33]

Differing Themes Across Sites

Of the 11 themes, four themes emerged as key differences in perceived barriers between academic and community oncologists.

Academic Sites.

Two themes were more often cited by academic oncologists compared to community oncologists. First, academic oncologists more commonly cited physician bias as a barrier (20%, n=10 vs. 6%, n=3). Misperceptions, such as ageism, discourage oncologists from considering the older adult population for clinical trial participation. As an example, an academic oncologist noted how physicians may perceive any older adults as frailer than any younger patients, causing them to withhold offering trials to this population based on chronologic age alone:

“Providers just don't offer people clinical trials, particularly older individuals, just because of their age.” [P2]

Second, academic oncologists frequently cited physician time (8%, n=4 vs. 2%, n=1). The difficulty and/or inefficiency of investing time into enrolling older adults discouraged oncologists from offering a clinical trial. For example, an academic oncologist explained how the comorbidities in an older patient requires a greater time investment in screening for trial eligibility:

“Older patients [have]…more medications [and] co-morbid conditions. To take an extra hour every single day, to make sure [older adults] fit the eligibility criteria, would be a challenge.” [P6]

Community Sites.

Two themes more frequently cited among community oncologists compared to academic oncologists. One of these themes was older adult attitudes and beliefs toward clinical trials (17%; n=9 vs. 4%, n=2). A patient’s misperceptions of clinical trials, such as the fear of experimentation or a placebo, discourages trial participation. Some community oncologists highlight the difficulty of addressing these misperceptions in older adults:

“Sometimes it is a matter of [an older adult’s] understanding of trials.” [P39]

The other theme was caregiver burden, where the emotional and logistical demands on a caregiver influence an older adult to decline trial participation (12%, n=6 vs. 0%, n=0). For example, a community oncologist noted the inherent logistical demands on this stakeholder:

“[It is] difficult for the caretaker to see all the regimented protocol visits, [and to] bring [the patient] in on a certain time.”[P27]

DISCUSSION

In order to increase clinical trial enrollment among older adults with cancer, we must better understand the multifaceted barriers to the enrollment of this vulnerable population. Although many studies have focused on academic oncologists’ perceived barriers and experiences, few studies have examined community oncologist perspectives. This is the first qualitative study, to our knowledge, to characterize the barriers to clinical trial participation of older adults with cancer among both academic and community oncologists.

There are two major findings from this study. One finding is that system-related (e.g., stringent eligibility criteria) and physician-related (e.g., oncologists’ concerns for treatment toxicities) barriers were the most frequently cited challenges among medical oncologists in both practice settings. This finding aligns with the prior literature. Overly stringent eligibility criteria has been frequently noted as a systemic barrier preventing the participation of older adults on cancer clinical trials2,5,11,17,19-23,54. Ongoing efforts are underway to address this systemic problem, including the National Institutes of Health’s Inclusion Across the Lifespan Policy.55 In addition, the American Society of Clinical Oncology,3 Friends of Cancer Research,6 and the Food and Drug Administration recently published recommendations to broaden and modernize clinical trial criteria.56 These are important strides forward, but it remains too early to assess if these initiatives will be sufficient for improving trial participation of the geriatric oncology population.

Oncologist concerns for treatment toxicities was also a common theme identified among both academic and community medical oncologists. Multiple efforts to alleviate physician concerns, including geriatrician consultation,57-62 multidisciplinary geriatric evaluations,63 geriatric assessments,64-67 and educational interventions,25 have been attempted. Utilization of the geriatric assessment, in particular, to examine factors other than chronological age might help oncologists make better decisions regarding treatment. Interventions that can help oncologists better understand the risks and benefits of treatment are needed to address their concerns to enrolling older adults on cancer clinical trials. Tools that can predict and anticipate toxicity to cancer treatment in the geriatric oncology population may promote better communication about risks and benefits.68 Consequently, this information may alleviate oncologists’ concerns for toxicity when considering older adults for cancer clinical trials.

The other major finding of this study is that there are differences in the barriers to clinical trial accrual identified between academic and community oncologists. While academics more frequently cited physician-related barriers (e.g., physician bias, lack of time/support) compared to community oncologists, community oncologists more frequently cited patient- and caregiver-related barriers (e.g., older adult attitudes/beliefs and caregiver burden) compared to academic oncologists. This finding suggests that there are different barriers faced by oncologists in different practice settings. Furthermore, these findings suggest that there are key gaps of knowledge in our current understanding of the barriers to clinical trial accrual. For example, while several studies have focused on exploring physician-related barriers that are relevant in academic settings,17-23,44,69 few studies have focused on evaluating caregiver-related factors that may be more prevalent in community settings.17,19,21,69 Future studies should focus on capturing the unique needs of different practice settings.

Findings from this study are significant because they demonstrate that although there are barriers (e.g. eligibility criteria, oncologist concerns for increased toxicity) that are universal among all practices, there are also unique, specific problems perceived by oncologists based on their practice setting. By better understanding the needs of individual practice settings, we may be better equipped to design more appropriate interventions for increasing accrual. To date, only one prior intervention has been tested to address this problem specifically in the geriatric population, which focused on improving oncologists’ education of treating this population.25 However, it was not successful at improving older adult accrual to studies. Thus, future interventions must be tailored to address the specific needs of individual clinical practices; there is no “one size fits all.”

While there are many strengths to our study, there are several limitations as well. First, it was conducted within a single health network with a small sample, so our findings may not represent oncologist attitudes in the general population. Second, our results may not be relevant for community practices without an affiliation to an academic center or similar support. Community oncologists that participated in this study were affiliated with the City of Hope main campus. This affiliation supports community sites with an infrastructure to conduct clinical trials that are led by principal investigators at the main campus. Third, there is the possibility of social desirability bias in the interviews; oncologists may have felt obligated to understate the barriers they face to enrolling older adults to the interviewer, who is a member of a team dedicated to geriatric oncology research. To minimize this potential bias, we ensured confidentiality by guaranteeing the de-identification of interview data. Finally, this study is a qualitative study and a hypothesis-generating analysis. Therefore, we are unable to make claims beyond reporting the perceptions of interviewees. Despite these limitations, this study provides important insights into the details regarding trial accrual, which may inform the design of future interventions.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight community and academic medical oncologists’ perceived barriers to older adult participation in cancer clinical trials. We show that barriers identified by oncologists are multifaceted, and that perceptions of barriers can differ importantly by practice setting. Academic oncologists more frequently cited physician-related barriers than community oncologists, while community oncologists more frequently cited patient- and caregiver-related barriers than academic oncologists. Thus, these findings highlight the complexity in designing effective interventions and the importance of tailoring these interventions to address the unique challenges at the level of each stakeholder. Further research is necessary to examine how these tailored interventions can address the barriers identified with oncologists.

Acknowledgements:

We dedicate this work to honor our beloved mentor, colleague, and coauthor, Dr. Arti Hurria, who lost her life tragically during the preparation of this manuscript. Dr. Hurria was a leader in geriatric oncology and an advocate for improving the enrollment of older adults in cancer clinical trials. We are committed to carrying her legacy forward.

Funding: The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under award numbers 5K12CA001727 (Clinical Scholar: Sedrak), the SWOG Coltman Fellowship Award from The Hope Foundation (PI: Sedrak), and National Institute on Aging (NIA) under award numbers K24AG056589 (PI: Mohile), K24AG0693 (PI: Dale), and R21AG059206 (MPI: Mohile, Dale, Hurria). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors: the NCI, The Hope Foundation, and NIA had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Previous Presentation: Results of this study were previously presented as an oral abstract at the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) in Amsterdam, Netherlands on November 17, 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, et al. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):10009–10009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, et al. Designing Therapeutic Clinical Trials for Older and Frail Adults With Cancer: U13 Conference Recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(24):2587–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. Improving the Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer : American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(32):3826–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurria A, Naylor M, Cohen HJ. Improving the quality of cancer care in an aging population: recommendations from an IOM report. Jama. 2013;310(17):1795–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. Improving the Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(32):3826–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, et al. Broadening Eligibility Criteria to Make Clinical Trials More Representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Stateme nt. Journal of clinical oncology: officialjournal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(33):3737–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtman SM, Harvey RD, Damiette Smit MA, et al. Modernizing Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-Friends of Cancer Research Organ Dysfunction, Prior or Concurrent Malignancy, and Comorbidities Working Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(33):3753–3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohile SG, Hurria A, Cohen HJ, et al. Improving the quality of survivorship for older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(16):2459–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimmick G, Correspondence A, Kimmick G Duke Cancer Institute DUMCB, States DU. Clinical trial accrual in older cancer patients: The most important steps are the first ones. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2016;7(3):158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(13):3112–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurria A Clinical trials in older adults with cancer: past and future. 2007;21(3):351–358; discussion 363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggstrom MQ, Waqar SN, Sezhiyan AK, et al. Barriers to enrollment in non-small cell lung cancer therapeutic clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(1):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, et al. Designing therapeutic clinical trials for older and frail adults with cancer: U13 conference recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2587–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaas R, Hart AA, Rutgers EJ. The impact of the physician on the accrual to randomized clinical trials in patients with primary operable breast cancer. 2005;14(4):310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel CL, Li Y, Beckett L, et al. An evaluation of barriers to accrual in the era of legislation requiring insurance coverage of cancer clinical trial costs in California. Cancer J. 2004;10(5):294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A. The Role of Clinical Trial Participation in Cancer Research: Barriers, Evidence, and Strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:185–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornblith AB, Kemeny M, Peterson BL, et al. Survey of oncologists' perceptions of barriers to accrual of older patients with breast carcinoma to clinical trials. Cancer. 2002;95(5):989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(12):2268–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javid SH, Unger JM, Gralow JR, et al. A Prospective Analysis of the Influence of Older Age on Physician and Patient Decision-Making When Considering Enrollment in Breast Cancer Clinical Trials (SWOG S0316). The Oncologist. 2012;17(9):1180–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamaker ME, Seynaeve C, Nortier JW, et al. Slow accrual of elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer in the Dutch multicentre OMEGA study. Breast. 2013;22(4):556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman RA, Dockter TJ, Lafky JM, et al. Promoting Accrual of Older Patients with Cancer to Clinical Trials: An Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Member Survey (A171602). The oncologist. 2018;23(9):1016–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore DH, Kauderer JT, Bell J,Curtin JP, Van Le L. An assessment of age and other factors influencing protocol versus alternative treatments for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer referred to me mber institutions: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic oncology. 2004;94(2):368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCleary NJ, Hubbard J, Mahoney MR, et al. Challenges of conducting a prospective clinical trial for older patients: Lessons learned from NCCTG N0949 (alliance). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2018;9(1):24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee KW, Pater JL, Pho L, Zee B, Siu LL. Enrollment of older patients in cancer treatment trials in Canada: why is age a barrier? Journalof clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(8):1618–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimmick GG, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Improving accrual of older persons to cancer treatment trials: a randomized trial comparingan educational intervention with standard information: CALGB 360001. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(10):2201–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crome P, Lally F, Cherubini A, et al. Exclusion of older people from clinical trials: professional views from nine European countries participating in the PREDICT study. Drugs & aging. 2011;28(8):667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nabhan C, Jeune-Smith Y, Klinefelter P, Kelly RJ, Fein berg BA. Challenges, Perceptions, and Readiness of Oncology Clinicians for the MACRA Quality Payment Program. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(2):252–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desch CE, Blayney DW. Making the Choice Between Academic Oncology and Community Practice: The Big Picture and Details About Each Career. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2(3):132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang JLY, Ross K. It’s Time to Increase Community Hospital-Based Health Research. Academic Medicine. 2017;92(6):727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey M, Boyes AW, Smits R, Bryant J, Waller A, Olver I. Access to clinical trials among oncology patients: results of a cross sectional survey. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):653–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Likumahuwa S, Song H, Singal R, et al. Building research infrastructure in community health centers: a Community Health Applied Research Network (CHARN) report. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellera C, Praud D, Petit-Moneger A, McKelvie-Sebileau P,Soubeyran P, Mathoulin-Pelissier S. Barriers to inclusion of older adults in randomised controlled clinical trials on Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(7):812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denson AC, Mahipal A. Participation of the elderly population in clinical trials: barriers and solutions. Cancer Control. 2014;21(3):209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Bolen S, et al. Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005(122):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gouverneur A, Salvo F, Berdai D, et al. Inclusion of elderly or frail patients in randomized controlled trials of targeted therapies for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2018;9(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazmierska J, Correspondence A, Kazmierska J Radiotherapy Department Ii GPCC, Garbary St PPEjkwp. Do we protect or discriminate? Representation of senior adults in clinical trials. Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy. 2013;18(1):6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore DH, Kauderer JT, Bell J, Curtin JP, Van Le L. An assessment of age and other factors influencing protocol versus alternative treatments for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer referred to member institutions: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2004; 94(2):368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puts MTE, Monette J, Girre V, et al. Participation of older newly-diagnosed cancer patients in an observational prospective pilot study: an example of recruitment and retention. BMC cancer. 2009;9:277–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Javid SH, Unger JM, Gralow JR, et al. A prospective analysis of the influence of older age on physician and patient decision-making when considering enrollment in breast cancer clinical trials (SWOG S0316). 2012;17(9):1180–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamaker M, Seynaeve C, Nortier J, et al. Slow accrual of elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer in the Dutch multicentre OMEGA study. 2013;22(4):556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Townsley CA, Chan KK, Pond GR, Marquez C, Siu LL, Straus SE. Understanding the attitudes of the elderly towards enrolment into cancer clinical trials. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayodele O, Akhtar M, Konenko A, et al. Comparing attitudes of younger and older patients towards cancer clinical trials. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(3):162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basche M, Baron AE, Eckhardt SG, et al. Barriers to enrollment of elderly adults in early-phase cancer clinical trials. Journal of oncology practice. 2008;4(4):162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prieske K, Trillsch F, Oskay-Ozcelik G, et al. Participation of elderly gynecological cancer patients in clinical trials. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2018;298(4):797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freedman RA, Tolaney SM. Efficacy and safety in older patient subsets in studies of endocrine monotherapy versus combination therapy in patients with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer: a review. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2018;167(3):607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of advanced nursing. 2008;62(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences. 2013;15(3):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bengtsson M How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacPhail C, Khoza N, Abler L, Ranganathan M. Process guidelines for establishing Intercoder Reliability in qualitative studies. Qualitative Research. 2015;16(2):198–212. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levit LA, Singh H, Klepin HD, Hurria A. Expanding the Evidence Base in Geriatric Oncology: Action Ite ms From an FDA-ASCO Workshop. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(11):1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernard MA, Clayton JA, Lauer MS. Inclusion Across the Lifespan: NIH Policy for Clinical ResearchNIH Policy for Inclusion Across the Lifespan in Clinical ResearchNIH Policy for Inclusion Across the Lifespan in Clinical Research. Jama. 2018;320(15):1535–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American society of clinical oncology and friends of cancer research joint research statement. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(33):3737–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurrea Arroyo J, Bollain IG, Esquiu CP. Multidisciplinary treatment plans in the adult patient- step by step and rationale. The European journal of esthetic dentistry : official journal of the European Academy of Esthetic Dentistry. 2012;7(1):18–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rouge-Bugat ME, Gerard S, Balardy L, et al. Impact of an oncogeriatric consulting team on therapeutic decision-making. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2013;17(5):473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horgan AM, Leighl NB, Coate L, et al. Impact and feasibility of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in the oncology setting: a pilot study. American journal of clinical oncology. 2012;35(4):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caillet P, Canoui-Poitrine F, Vouriot J, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in the decision- making process in elderly patients with cancer: ELCAPA study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(27):3636–3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulkes KJ, Souwer ET, Hamaker ME, et al. The Effect of A Geriatric Assessment on Treatment Decisions for Patients with Lung Cancer. Lung. 2017;195(2):225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaibi P, Magne N, Breton S, et al. Influence of geriatric consultation with comprehensive geriatric assessment on final therapeutic decision in elderly cancer patients. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2011;79(3):302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huillard O, Boudou-Rouquette P, Chahwakilian A, et al. Multidisciplinary risk assessment to reveal cancer treatments in complex cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(31_suppl):170–170. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mertens C, Le Caer H, Ortholan C, et al. 1050PDThe ELAN-ONCOVAL (ELderly heAd and Neck cancer-Oncology evaluation) study: Evaluation of the feasibility of a suited geriatric assessment for use by oncologists to classify patients as fit or unfit. Annals of Oncology. 2017;28(suppl_5):mdx374.007–mdx374.007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulahssass R, Gonfrier S, Isabelle B, et al. Influence of the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in elderly metastatic cancer patients. Analysis from a prospective cohort of 1048 patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(15_suppl):10045–10045. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Girre V, Falcou MC, Gisselbrecht M, et al. Does a geriatric oncology consultation modify the cancer treatment plan for elderly patients? The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2008;63(7):724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aliamus V, Adam C, Druet-Cabanac M, Dantoine T, Vergnenegre A. [Geriatric assessment contribution to treatment decision-making in thoracic oncology]. Revue des maladies respiratoires. 2011;28(9):1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012; 118(13):3377–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Townsley CA, Chan KK, Pond GR, Marquez C, Siu LL, Straus SE. Understanding the attitudes of the elderly towards enrolment into cancer clinical trials. BMC cancer. 2006;6:34–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]