Abstract

Women with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often report fatigue, along with abdominal pain and psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety). There is little information about the relationships among these symptoms. Using a secondary data analysis (N = 356), we examined the relationship between abdominal pain and fatigue; and whether psychological distress mediates the effect of abdominal pain on fatigue both across-women and within-woman with IBS. Data gathered through a 28-day diary were analyzed with linear regressions. The across-women and within-woman relationships among same-day abdominal pain, fatigue and psychological distress were examined. Within-woman relationships were also examined for directionality among symptoms (i.e., prior-day abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue, prior-day fatigue predicts next-day abdominal pain). In across-women and within-woman analyses on the same-day, abdominal pain and fatigue were positively correlated. In within-woman analyses, abdominal pain predicted next-day fatigue, but fatigue did not predict next-day pain. In across-women and within-woman analyses, psychological distress partially mediated the effects of abdominal pain on fatigue. Symptom management incorporating strategies to decrease both abdominal pain and psychological distress are likely to reduce fatigue. Nursing interventions, such as self-management skills to reduce abdominal pain and psychological distress, may have the added benefit of reducing fatigue in IBS.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue, abdominal pain, depression, anxiety

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder seen by health care providers (Drossman et al., 2016). It affects approximately 22 million people in the United States (U.S.), representing 14% of the population (Lovell & Ford, 2012). The worldwide prevalence of IBS in adults is between 9% and 24% (Lovell & Ford, 2012). IBS is predominantly reported by women, with 2 to 3 women for every 1 man affected in the U.S. Direct health care costs for IBS in the U.S. ranges from $742 to $7,547 per patient annually. Indirect costs such as over-the-counter medications, lost productivity, and time spent seeking health care providers add to patients’ expenses (Hulisz, 2004). These burdens of illness make IBS a significant public health issue.

Until 2016, the diagnosis of IBS was based on the Rome III criteria. To meet Rome criteria, a person has to have recurrent abdominal pain that occurs at least 3 days/month for the last 3 months, and that is associated with 2 or more of the following: (a) improvement with a bowel movement, (b) a change in stool frequency, and (c) a change in stool form. In addition, the symptoms need to be present for at least 6 months prior to the IBS diagnosis (Drossman & Dumitrascu, 2006). For randomized clinical trials, participants need to have symptoms at least 2 days/week across the assessment period. Predominant bowel pattern determines IBS subtypes: these include constipation-predominant (IBS-C), diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), mixed diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M), and unsubtyped (IBS-U) (Drossman et al., 2016). Individuals with IBS often experience additional GI symptoms (e.g., bloating, intestinal gas, and urgency) and non-GI symptoms (e.g., fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and extra-intestinal pain) (Lackner, Gudleski, DiMuro, Keefer, & Brenner, 2013).

Fatigue is one of the most common and disturbing extra-intestinal symptoms reported by patients with IBS (Frändemark, Jakobsson, Törnblom, Simrén, & Jakobsson, 2017; Lackner et al., 2013). Patients with IBS describe their fatigue as “extreme weariness and a state of being very tired” (Han & Yang, 2016). In a study by Lackner et al., (2013), 61% of 176 IBS patients reported fatigue at least as ‘moderate’, and 71% of patients reported fatigue at least 50% of the time over the previous 3 months. In another study, all IBS patients (N = 160) reported fatigue with 40% rating their fatigue as ‘severe’, 34% as ‘moderate’, and 26% as ‘mild’ (Frandemark et al., 2017). In a systematic review and meta-analysis with 24 studies, the pooled frequency of fatigue in IBS was 54.2% (Han & Yang, 2016). Fatigue is associated with reductions in work productivity, interference with daily activities, and reduced health-related quality of life (Frändemark et al., 2017; Han & Yang, 2016; Lackner et al., 2013).

As noted above, patients with IBS often report fatigue, along with abdominal pain and psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety) (Han & Yang, 2016; Lackner et al., 2013; Simren, Svedlund, Posserud, Bjornsson, & Abrahamsson, 2008). Abdominal pain, the predominant symptom as well as the main diagnostic criterion for IBS, impacts quality of life and increases psychological distress (Drossman et al., 2016; Heitkemper et al., 2011). Severe abdominal pain is linked with visceral hypersensitivity and autonomic nervous system dysfunction (Heitkemper et al., 2011), and an imbalance of immune responses in IBS (Martin - Viñas, & Quigley, 2016). In a systematic review of the comorbidity of IBS (Whitehead, Palsson, & Jones, 2002), psychological distress is defined as symptoms of unpleasant feeling or emotions in IBS, and especially depression and anxiety occur in up to 94% of patients with IBS.

In a study of women with moderate-severe functional bowel disorders (N = 211), investigators noted that women with severe abdominal pain when compared to those with mild abdominal pain, reported higher depression and anxiety (Drossman, Whitehead, et al., 2000). In women with IBS (N = 20), those with reduced central pain modulation of peripheral stimuli during experimental testing reported more days with ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ psychological distress (Jarrett et al., 2014). An earlier study in 97 women with IBS (Jarrett et al., 1998) demonstrated that the mean daily turmoil score (anger, anxiety, depression, feelings of guilt, hostility, impatient-intolerant, irritable, tearfulness-crying easily, and tension) was positively associated with the mean daily GI symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and intestinal gas. As such, the severity and frequency of abdominal pain is linked with psychological distress in women with IBS.

Furthermore, abdominal pain and psychological distress were the most significant predictors of fatigue with retrospective measures in IBS (Han & Yang, 2016; Lackner et al., 2013). In other patient groups, e.g., cancer (Oh & Seo, 2011) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (Winger et al., 2014), fatigue is also associated with both pain and psychological distress. For example, in a case-control study in patients with CFS (N = 120) and healthy controls (N = 39), patients with CFS reported more severe pain and lower pain thresholds (Winger et al., 2014). Such evidence supports the link between pain sensitivity and fatigue. In a large urban population-based study (15,222 men, and 16,429 women), chronic pain and psychological distress were significant predictors of attributed fatigue (Pawlikowska et al., 1994).

Taken together, abdominal pain and psychological distress may contribute to the severity of fatigue in patients with IBS. However, the examination of the relationships among abdominal pain, psychological distress, and fatigue have primarily relied on one-time retrospective measures of these symptoms in IBS. As such, data on the temporal relationships of these symptoms is scant; and whether psychological distress plays a key role in mediating the relationship of abdominal pain to self-reported fatigue in women with IBS is unknown.

Our first aim was to examine the temporal relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue both across-women and within-woman with IBS. By examining daily symptom reports across-women, we could ask whether women who rate abdominal pain high overall tend to rate fatigue high (i.e., across-women relationships). To capture the within-person fluctuations in symptoms over time (Buchanan et al., 2014), we examined the co-variation of symptom variables within-person to describe the temporality of the relationship between abdominal pain and fatigue. Using a within-woman approach, we can answer the question of whether an individual’s ‘next-day’ fatigue is greater than average after days when that person’s abdominal pain is worse than average (i.e., within-woman relationships). Understanding the temporal relationships among symptoms (e.g., which comes first, pain, psychological distress, or fatigue), especially when symptoms are sporatic, could provide guidane to patients for self-management to best manage multiple co-occurring symptoms in IBS (Guthrie et al., 2003).

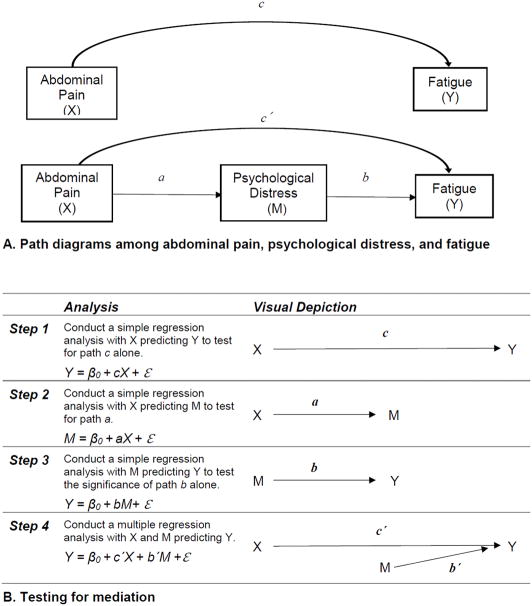

The second aim of the study was to determine whether psychological distress mediates the temporal relationships of abdominal pain with fatigue in across-women and within-woman with IBS. Graphical representation of proposed mediation effect is described in Figure 1A and 1B. Mediation is a hypothesized causal chain in which one variable (X) affects a second variable (M [mediator]) that, in turn, affects a third variable (Y) (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The mediation effect, in which X leads to Y through M, represents the portion of the relationship between X and Y that is mediated by M (Bennett, 2000). Mediation analysis was used to address the question of whether psychological distress contributes to the link between abdominal pain and fatigue.

Figure 1(A & B).

Conceptual diagram for mediation model.

Note. X indicates an independent variable. M indicates a mediator. Y indicates a dependent variable. β0 indicates an intercept. ε indicates independently distributed normal errors. Total effect of X on Y: c = ab + c′, Direct effects of X on M: a; Direct effects of M on Y after controlling for X: b; Direct effect of X on Y after controlling for M: c′ = c – ab, Indirect effect of X on Y: c - c′ = ab. Mediation effect (i.e., path ab) is supported if (1) the path b remains significant when controlling for X, and (2) the path c > c′ (partial mediation) or path c′ decreases to zero or non-significant (full mediation) with M in the model (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

To accomplish aims 1 and 2, we used three models. For both across-women and within-woman analyses, we examined the relationships of abdominal pain with fatigue on the same day (i.e., Model-A). Since the within-woman relationship addresses day-to-day variations in abdominal pain and fatigue, we also examined the within-woman relationship in Model-B (examining whether the prior-day abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue) and Model-C (examining if the prior-day fatigue predicts next-day abdominal pain).

For aim 1, we hypothesized that the mean daily abdominal pain score (averaged over 28 days) would be a significant predictor of mean daily fatigue score (averaged over 28 days) in both across-women and within-woman analyses (Model-A). In the within-woman analyses, we hypothesized abdominal pain would predict next-day fatigue in Model-B, but not the reverse in Model-C. For aim 2, we hypothesized that the across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue would be weakened when controlling for psychological distress. However, a statistically significant indirect path between abdominal pain and fatigue through psychological distress would be present, indicating that psychological distress mediates the effect of abdominal pain on fatigue.

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of baseline data from two previous randomized controlled trials (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009). Study-1 was conducted from 2002 to 2007 (Jarrett et al., 2009) and Study-2 from 2008 to 2013 (Jarrett et al., 2016). In the ‘parent’ studies (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009), participants were recruited through community advertisement. To be included, participants had to have a medical diagnosis of IBS, be between 18 and 70 years of age, and meet the Rome-II (Study-1) or Rome-III (Study-2) criteria for IBS. Potential participants were excluded for co-existing GI pathology (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease), abdominal surgery, renal or reproductive pathology (e.g., endometriosis), or select medications (e.g., anticholinergics, cholestyramine, narcotics, colchicine, iron supplements, or laxatives).

Both ‘parent’ studies (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009) conducted by the same research team and same facilities, included men and women with IBS, and used similar baseline assessment and research methods: inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment, data collection, settings, and instruments, diagnostic criteria and paper formats of a daily health diary. Ford et al., (2013) showed that good agreement overall between the Rome II and Rome III criteria in diagnosing IBS. Thus, to achieve appropriate sample size of women with IBS, baseline data from both ‘parent’ studies were merged for the current study. Gender-related differences in abdominal pain, fatigue, and psychological distress are apparent in patients with IBS. Compared to men, women experience these symptoms more frequently and with higher severity (Cain et al., 2009). Thus, we included data collected on women only. The sample included 356 women with IBS (N = 255 from Study-1; N = 101 from Study-2).

Ethical Considerations

The two studies, Study-1 (Jarrett et al., 2009) and Study-2 (Jarrett et al., 2016), received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by the University of Washington (UW) Human Subject Division, prior to the recruitment. The IRB approval was renewed annually until each study was closed. Written consent was obtained prior to collecting baseline data (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009).

Procedures

In both ‘parent’ studies (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009), eligibility screening of participants occurred over the phone. Participants deemed eligible attended an in-persons session where written consent was obtained. Then, a health interview was conducted by a research nurse, and baseline questionnaires including demographics, clinical and symptom characteristics were completed. After the in-person visit, the participant completed a daily diary each evening for 28 days at home. As previously described, a gastroenterologist reviewed all baseline data to determine whether the diagnosis of IBS was appropriate or whether ‘red flags’ were present (Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarret et al., 2009). Demographic, clinical and symptom characteristics, and daily diary data from the baseline assessments of both ‘parent’ studies were used in this secondary data analysis.

Measures

Demographics

All participants completed a demographic data form that included age, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, occupation, and personal/family annual income levels.

Clinical and symptom characteristics

The clinical and symptom characteristics were assessed using a self-reported Health History Questionnaire including IBS-specific variables (e.g., IBS symptoms, diagnosis process, management strategies, and family history of GI diseases), and general health assessment including current and past illness, medication, lifestyle, and surgery. The mean internal consistency reliability was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). Criteria for functional GI disorders (e.g., IBS) as well as GI symptom-related items (e.g., bowel pattern subtypes) were assessed in Study-1 with the Rome II diagnostic questionnaire for functional GI disorders (Drossman, Corazziari, Talley, Thompson, & Whitehead, 2000) and in Study-2 with the Rome III questionnaire (Thompson, Drossman, Talley, Walker, & Whitehead, 2006). Average Cronbach’s α coefficient of the overall items in both questionnaires were 0.95 for Rome II questionnaire (Drossman, Corazziari, et al., 2000), and 0.98 for Rome III questionnaire (Thompson et al., 2006).

Daily diary symptoms

Participants completed a daily symptom diary with 33 items (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, intestinal gas, psychological distress, anger, fatigue, stressed, sleepiness during the day, urgency, and work and life interferences), each evening for 28 days to assess the severity of their symptoms experienced over the past 24 hours. Participants rated each symptom on a Likert scale of 0 (not present), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe), to 4 (very severe). For this study, abdominal pain, fatigue, and psychological distress were the focus. We computed a ‘psychological distress’ score by the average of depression and anxiety scores. Reliability of diary data was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.72).

Data Analyses

We used the merged datasets from both ‘parent’ studies. Using descriptive statistics (percentages, mean, standard deviation [SD]), we summarized demographics, clinical and symptom characteristics, and the symptoms reported in the diary. We compared these variables between the two studies using independent t-test (continuous variables) and Chi-square test (categorical variables). A linear regression was used to examine across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue, and a mediation effect of psychological distress between abdominal pain and fatigue. A mediation model testing is recommended only if the relationships between each pair of variables appear to be linear (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Thus, a partial Pearson correlation controlling for age and study design variables (i.e., Study-1, and Study-2) was performed.

To address the first aim of this study (i.e., across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue), we computed two summary measures for each woman, namely the means of daily abdominal pain and fatigue scores across the 28 diary days on the same day for the across-women relationships (Mode-A: relationships of abdominal pain with fatigue on the same day). To evaluate the within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue, a linear regression model was applied to each of the three models (Model-A: relationships of abdominal pain with fatigue on the same day; Model-B: the prior-day abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue; Model-C: the prior-day fatigue predicts next-day abdominal pain). For example, in Model-A, we fit a linear regression model that included the ‘deviation’ of daily abdominal pain score in women i on day t from mean of abdominal pain score in woman i as a dependent variable. We also included the ‘deviation’ of daily fatigue score in woman i on day t from mean of fatigue score in woman i as an independent variable. Details of fitted linear regression models for across-women and within-woman analyses are described in Supplementary Table 1.

To address the aim 2, the examination of the mediation effects of psychological distress between abdominal pain and fatigue, we followed Baron and Kenny’s four steps (Baron & Kenny, 1986) using linear regression analyses controlling for psychological distress (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 1B represents a four-step approach for testing a mediation effect (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Step 1 (path c): X is a significantly associated with Y; Step 2 (path a): X is significantly associated with M; Step 3 (path b): M is significantly associated with Y. In Step 4 (path c′), a mediation effect is supported if two conditions are met: (1) the mediator (M) is a significant predictor of the outcome variable (Y) when controlling for X; (2) the effect of X on Y will become zero, or weakened, when M is included in the regression. If the effect of X on Y completely disappears (zero, or non-significant), M fully mediates between X and Y (full mediation). If the effect of X on Y still exists, but in a smaller magnitude, M partially mediates between X and Y (partial mediation) (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes, 2009). Step 1 was performed as part of Aim 1. We examined for a mediation effect (Aim 2) only if there was a significant direct association between fatigue and abdominal pain (Bennett, 2000). To determine if the mediation effect is truly meaningful (Hayes, 2009), we used a bootstrapped statistical test of the mediation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Merged data from Study-1 and Study-2: Relationships of Abdominal Pain with Fatigue in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS; N = 356).

| Main models | Models controlling for depression and anxiety (day = t) | Bootstrap results for significances of mediation effectc | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | SE | t | pb | βa | SE | t | pb | βa,d | SE | 95% CI | z | pb | |

| Acrosse-Women Same Day Model-A: Relationships of Abdominal Pain (day = t) with Fatigue (day = t) | |||||||||||||

| Across | 488 | .017 | 10.1 | <.001 | .333 | .017 | 7.1 | <.001 | .155 | .012 | .110 to .192 | 3.94 | <.001 |

| Within-Woman | |||||||||||||

| Same Day Model-A: Relationships of Abdominal Pain (day = t) with Fatigue (day = t) | |||||||||||||

| Within | .174 | .010 | 16.5 | <.001 | .138 | .010 | 13.3 | <.001 | .036 | .006 | .001 to .071 | 6.04 | <.001 |

| Day-to-Day Model-B: Abdominal Pain (day = t) Predicts Next-day Fatigue (day = t+1) | |||||||||||||

| Within | .059 | .011 | 5.5 | <.001 | .046 | .010 | 4.4 | .001 | .013 | .003 | .009 to .021 | 4.90 | <.001 |

| Reverse Model-C: Fatigue (day = t) Predicts Next-day Abdominal Pain (day = t+1) | |||||||||||||

| Within | .020 | .011 | 1.8 | .060 | .005 | .011 | 0.5 | .618 | Not applicablef | ||||

Note. CI = confidence interval. SE = standard error.

standardized β-coefficient.

testing the significance of β-coefficient.

resamples n = 1,000.

mediation effect testing for ‘β in main model’-’β controlling for psychological distress’

controlling for age and study design (Study-1 and Study-2) in across-women analyses.

due to non-significant relationship of reverse model-C.

In across-women analyses, we controlled for age and study design (i.e., Study-1 and Study-2) as potential confounding variables in merged datasets. In all analyses mentioned above, a p value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were two-tailed. All analyses except for a bootstrapped test were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, USA). A bootstrapped test was performed using R-3.2.2 software.

Results

Demographics, and Clinical/Symptom Characteristics

In merged datasets from Study-1 and Study-2 (Table 1), the majority of the women identified themselves as Caucasian (88%), married (55%), and with a college or graduate degree (75%). Participants’ reported bowel pattern subtypes were IBS-D (40%), IBS-C (22%), and IBS-M (19%). Participants reported having had symptoms of IBS for 10 ± 0.7 years on average; and a health care provider diagnosis an average of 8 ± 0.7 years prior to study enrolment. In merged datasets, all women with IBS (N = 356) reported at least ‘mild’ abdominal pain, fatigue, and psychological distress. Women reported on average 36% of diary days they experienced ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ fatigue. The mean severity of abdominal pain and fatigue were higher than that reported for depression and anxiety (Table 2). There were no differences in demographics, clinical and symptom characteristics between the two studies (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| Study-1 (N = 255) | Study-2 (N= 101) | Merged (N = 356) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 43.2 (14.1) | 40.1 (14.9) | 42.1 (14.0) | .623 |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .458 | |||

| Caucasian | 231 (90.6) | 82 (82.2) | 313 (87.9 ) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 9 (3.5) | 8 (0.9) | 17 (4.8) | |

| Asian | 16 (7.1) | 7(6.9) | 23 (6.5) | |

| Black/African American | 11 (4.3) | 9 (8.9) | 20 (5.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Married/Partnered, n (%) | 143 (56.0) | 52 (51.5) | 197 (55.4) | .529 |

|

| ||||

| ≥ College graduate, n (%) | 192 (75.4) | 75 (74.2) | 267 (75.0) | .721 |

|

| ||||

| Occupation, n (%) | .872 | |||

| Professional, managerial | 95 (36.3) | 36 (35.6) | 131 (36.8) | |

| Technical, service, sales | 58 (22.7) | 9 (8.9) | 67 (18.8) | |

| Student | 29 (11.4) | 23 (22.8) | 52 (14.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Income ≥ $ 60,000, n (%) | 91 (39.3) | 66 (48.0) | 157 (44.1) | .523 |

|

| ||||

| Predominant Bowel Pattern, n (%) | .423 | |||

| Constipation (IBS-C) | 47 (18.4) | 30 (29.7) | 77 (21.6) | |

| Diarrhea (IBS-D) | 90 (35.3) | 51 (50.5) | 141 (39.6) | |

| Mixed (IBS-M) | 52 (20.4) | 17 (16.8) | 69 (19.4) | |

| Unsubtyped (IBS-U) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (3.0) | 9 (2.5) | |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

testing the differences in mean symptom severity between the Study-1 and Study-2.

Table 2.

Mean Symptom Frequency and Severity in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| mean (SD) | Study-1 (N = 255) | Study-2 (N = 101) | Merged (N = 356) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean symptom severity (rating scale: 0 – 4 points) | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.3) | .999 |

| Fatigue | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.3) | .954 |

| Depression | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.3) | .891 |

| Anxiety | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.4) | .995 |

| Mean % of days with ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ for 28 days (rating scale: 0 – 100%) | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 36.9 (26.1) | 38.2 (26.5) | 37.8 (26.2) | .895 |

| Fatigue | 34.9 (27.7) | 36.2 (27.5) | 35.6 (27.6) | .821 |

| Depression | 9.9 (16.9) | 9.6 (17.8) | 9.8 (17.2) | .901 |

| Anxiety | 18.7 (22.2) | 19.5 (23.9) | 19.1 (23.0) | .934 |

Note.

Data are presented with mean and standard deviation (SD) using a daily diary over the past 24 hours for 28 days.

testing the differences in mean of symptoms between the Study-1 and Study-2.

Relationships of Abdominal Pain with Fatigue, and Psychological Distress as a Mediator

Pearson correlations

Prior to conducting linear regression analyses, the linear relationships between each pair of symptoms were examined using partial Pearson correlations controlling for age and study design variables. A statistically significant positive correlation was found between abdominal pain and fatigue (r = 0.49, p < .001), between abdominal pain and psychological distress (r = 0.38, p < .001), and between psychological distress and fatigue (r = 0.59, p <.001).

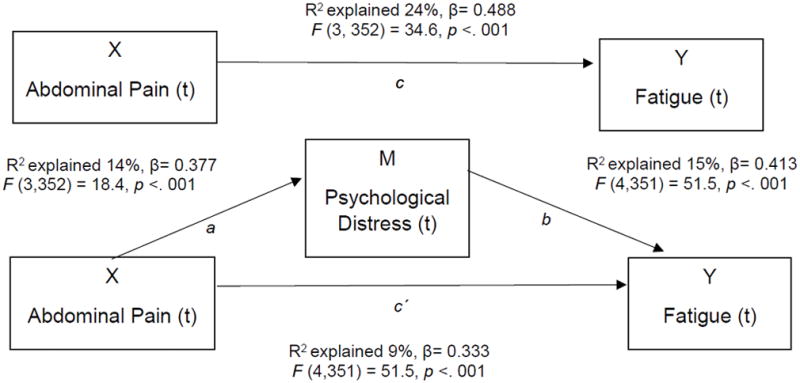

Across-women relationships

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, the across-women relationship between daily abdominal pain (X) and fatigue (Y) was positive and significant in path c (β = 0.488, p <.001). Abdominal pain explained 24% of the variance in fatigue. Our path a model shows that abdominal pain (X) is also positively related to psychological distress (M) with β = 0.377, p <.001. Abdominal pain explained 14% of the variance in psychological distress. Finally, the path c′ regressed fatigue (Y) on both abdominal pain (X) and psychological distress (M). This final regression equation in path c′ met the two requirements for a mediator effect. First, the hypothesized mediator, psychological distress (M), was a significant predictor (β = 0.413, p <.001) and explained 15% of the variance in fatigue (Y). Second, the variance in fatigue (Y) explained by abdominal pain (X) was reduced from 24% in the path c to 9% in the path c′; and the standardized regression coefficient β was decreased from 0.488 to 0.333 from path c to the path c′. While abdominal pain (X) continued to have a statistically significant effect on fatigue (Y) in path c′, the loss of 15% of explained variance in fatigue (Y) by abdominal pain (X) was attributed to mediation by psychological distress. In across-women analyses in Model-A, the mediation effect of psychological distress (testing path ab) with bootstrap methods was statistically significant (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Across-women relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue, with psychological distress as a mediator on the same day.

Note. X indicates a mean severity of abdominal pain; M indicates a mean severity of psychological distress; Y indicates a mean severity of fatigue; t indicates on day t. Total effect of X on Y: c; Direct effects of X on M: a; Direct effects of M on Y after controlling for X: b; Direct effect of X on Y after controlling for M: c′; Indirect effect of X on Y: c - c′ = ab.

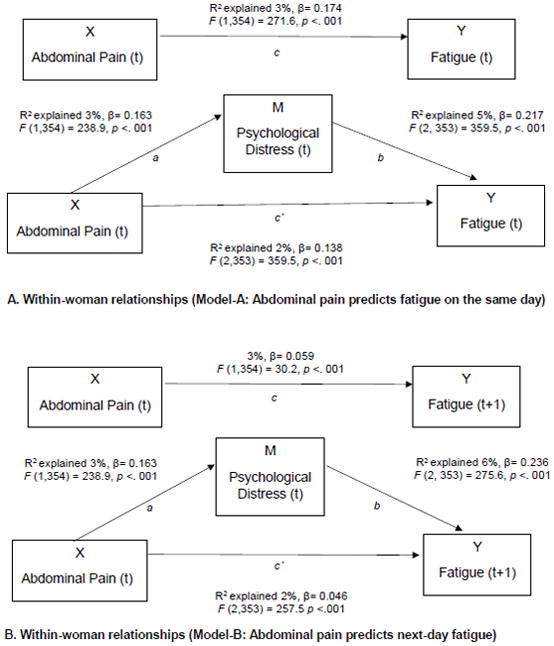

Within-woman relationships

We examined the within-women relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue in all three models: Model-A same-day relationship, Model-B abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue, and Model-C fatigue predicts next-day abdominal pain. The within-woman relationships between abdominal pain (X) and fatigue (Y) were positive and significant in Model-A and Model-B. However, fatigue did not predict next-day abdominal pain in Model-C (p = .060) (Table 3). Thus, we only examined the mediation effect of psychological distress in Model-A and Model-B (Figure 3A and 3B). In Model-A (Figure 3A), the within-woman relationship between daily abdominal pain (X) and fatigue (Y) was positive and significant in path c (β = 0.174, p <.001). Abdominal pain (X) explained 3% of the variance in fatigue (Y). Our path a shows that abdominal pain (X) is also positively related to psychological distress (M) with β = 0.163, p <.001. Abdominal pain (X) explained 3% of the variance in psychological distress (M). Finally, the path c′ regressed fatigue (Y) on both abdominal pain (X) and psychological distress (M). In path c′, the psychological distress (M) was a significant predictor (β = 0.217, p <.001) and explained 5% of the variance in fatigue (Y). In this path c′, which included both abdominal pain and psychological distress, abdominal pain (X) added 2% to explain variance in fatigue (Y) beyond the 5% contributed by psychological distress. The variance in fatigue (Y) explained by abdominal pain (X) was reduced from 3% in the path c model to 2% in the path c′; and the standardized regression coefficient β was decreased from 0.174 to 0.138 from path c to the path c′. The loss of 1% from path c to the path c′ of explained variance in fatigue (Y) by abdominal pain (X) was due to the mediation of psychological distress.

Figure 3(A & B).

Within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue, with psychological distress as a mediator (Model-A & Model-B).

Note. X indicates a mean severity of abdominal pain; M indicates a mean severity of psychological distress; Y indicates a mean severity of fatigue; ‘t’ indicates on day t; ‘t +1’ indicates on day (t + 1)’; Total effect of X on Y: c; Direct effect of X on M: a; Direct effect of M on Y after controlling for X: b; Direct effect of X on Y after controlling for M: c′; Indirect effect of X on Y: c - c′ = ab.

Model-B examined whether abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue (Figure 3B). The results in Model-B were comparable to the within-woman relationship in Model-A. Higher abdominal pain on the previous day leads to higher fatigue on the following day. Controlling for psychological distress on the previous day reduces the next-day fatigue within-woman. The mediation effects of psychological distress (testing path ab) in Model-A and Model-B with bootstrap methods were statistically significant (Table 3).

Discussion

Women with IBS experience psychological distress and fatigue in addition to abdominal pain. Across-women analyses confirmed that abdominal pain and fatigue were highly correlated (Table 3). In our within-woman analyses of the day-to-day variations in abdominal pain and fatigue, abdominal pain predicted next-day fatigue (p < .001). As expected, fatigue did not predict abdominal pain severity on the following day. Both across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue were partially mediated by psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety).

Our daily diary findings are consistent with previous IBS studies that utilized one-time retrospective measures. Using a symptom questionnaire, Lackner et al., (2013) found that the severity of IBS symptoms including abdominal pain as well as depression and anxiety were positively associated with fatigue. Lackner et al. suggested that a strong fear of GI symptoms and psychological distress might contribute to, or amplify the intensity of somatic sensations such as fatigue. Heightened psychological distress and fatigue are likely subsequent at least in part to living with an intermittent, painful condition (Lackner et al., 2013). In a separate sample of women with IBS using a daily diary, Heitkemper et al. (2011) also found that severe abdominal pain was associated with greater psychological distress and fatigue, regardless of bowel pattern subtypes. However, in that data set no attempt was made to examine the temporal pattern of symptom reporting. Our findings, while matching that of previous studies (Heitkemper et al., 2011; Lackner et al., 2013), extend this work by determining the temporal relationships, i.e., greater abdominal pain predicts next-day fatigue. Understanding this temporal relationship and incorporating this information into self-care planning may further enhance the effectiveness of cognitively-focused therapies for IBS. Thus, interventions should be inclusive of approaches to reduce abdominal pain and psychological distress to manage fatigue.

Our findings of the mediation effect testing support the hypothesis that psychological distress was at least one mediator (i.e., partial mediation) in both across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue. This finding indicates that there are other confounders or moderators, apart from psychological distress, that could also impact on across-women and within-woman relationships of abdominal pain with fatigue. Hertig, Cain, Jarrett, Burr, & Heitkemper (2007) found that daily stress was associated with abdominal pain and psychological distress. In a study of sleep in women with IBS (Buchanan et al., 2014), self-reported sleep disturbance predicted exacerbation of next-day abdominal pain, anxiety and fatigue, but no reverse relationships were found. Given these findings (Buchanan et al., 2014; Hertig et al. 2007), stress and sleep may confound or mediate across-women and within-woman relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue found in the current study.

In addition to stress and poor sleep, other possible confounding symptoms include GI symptoms such as diarrhea, constipation, urgency and bloating. Since there were no differences in the mean severity of daily abdominal pain, fatigue, and psychological distress across bowel pattern subgroups in Study-1 (Heitkemper et al., 2011) or Study 2, (unpublished data), we did not test these possible confounding variables in the models. It remains to be examined whether altered bowel patterns such as urgency in the IBS-D, and straining at stool in IBS-C might contribute to the relationships between abdominal pain and fatigue in our sample.

Although the etiology of fatigue remains largely unknown in IBS, a biological link between abdominal pain and fatigue may explain our findings of across-women and within-woman relationships in IBS. Imbalances in gut-derived serotonin (Cremon et al., 2011), stress-related release of catecholamines (Karling et el., 2011), and potential inflammation-linked release of cytokines (Shulman, Jarrett, Cain, Broussard, & Heitkemper, 2014), are associated with abdominal pain and psychological distress in IBS. These biochemical factors are also considered important in the pathophysiology of fatigue in chronic diseases such as cancer, CFS, and fibromyalgia (Landmark-Høyvik et al., 2010). Thus, these may also serve as biomarkers for fatigue and/or a symptom cluster of pain-psychological distress-fatigue in IBS. Whether variants in genes that regulate the expression of neurotransmitters or cytokines account for a symptom cluster of pain-psychological distress-fatigue in patients with IBS awaits study. Moreover, Nagy-Szakal et el. (2017) recently reported on a study of fecal microbiome and metabolome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/CFS with and without co-morbid IBS and healthy controls. The presence of co-morbid IBS more strongly distinguished the bacterial and metabolomic signatures in patients with ME/CFS compared to healthy controls. This raises the question of whether fecal microbiome and their metabolites contribute to symptoms of abdominal pain, psychological distress, and fatigue.

In the current data set, participants were enrolled using Rome II (Study-1) or Rome III (Study-2) criteria. Recently, the Rome IV IBS diagnostic criteria were released (Drossman, 2016). The congruency of the Rome IV with Rome III criteria was tested in a Chinese population (N = 1,376) by Bai et al. (2017). Approximate half of patients who met the criteria for IBS using the Rome III criteria met the Rome IV criteria for IBS. There were no significant differences in stool frequency and IBS bowel pattern subtypes between Rome III IBS patients and Rome IV IBS patients. However, those meeting Rome IV criteria had a higher severity of abdominal pain and psychological distress compared to those diagnosed using Rome III criteria (Bai et al., 2017). The magnitude of the relationship between the two variables depends on whether the values of two variables are significantly different from zero (Mukaka, 2012). In our study, the overall symptom severities of daily abdominal pain (mean = 1.4) and fatigue (mean = 1.2) were mild (Table 2). Therefore, we conjecture that had Rome IV criteria been available at the time of our participant recruitment, the relationships among abdominal pain, psychological distress and fatigue may have been stronger. Issues such as changing diagnostic criteria add to the complexity of symptom science research in functional gastrointestinal disorders.

To better characterize the relationships among abdominal pain, fatigue, and psychological distress, studies employing longitudinal follow-up of Rome IV diagnosed IBS patients with measurement of each symptom at different time points are warranted. Using a causality analysis with time series or symptom cluster approaches such as structural equation modeling (Rabe-Hesketh, Skrondal, & Zheng, 2007) may provide more insights into symptom inter-relationships. Given the high prevalence of daily fatigue in women with IBS, a variety of biological factors in relation to fatigue should be investigated. Future intervention studies are also warranted to examine whether comprehensive self-management strategies that are effective in reducing abdominal pain and psychological distress also reduce fatigue in patients with IBS.

The present study has several strengths. First is the inclusion of a relatively large sample of IBS participants who maintained daily diaries. Second, prospective diary data analyses provided insights into the directionality of the relationships among abdominal pain, psychological distress, and fatigue. However, several study limitations need to be acknowledged. The results of our model testing are limited by the nature of cross-sectional design. We cannot make definitive conclusions about causal relationships, even when changes in fatigue were preceded by changes in psychological distress and abdominal pain. It is unclear whether, in a single day, the abdominal pain existed before the onset of psychological distress. The results from this cross-sectional study should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the average daily abdominal pain, fatigue and psychological distress levels were most often rated as ‘mild’ to ‘moderate’ (Table 2), which limits information on patients with severe symptoms most likely found in tertiary care clinics. The gender was restricted to women and the ethnicity was primarily Caucasian, thus limiting generalizability of results beyond white women. (Gralnek, Hays, Kilbourne, Chang, & Mayer, 2004). We used self-reported measures, and participants were self-selected to participate in an intervention trial. Self-reported measures are often wrought with recall and response bias. There may be differences in symptom reporting based on motivation to participate in a clinical trial. This self-selection method potentially limits the generalizability of our findings (Althubaiti, 2016).

Implications for Nursing Practice

Clinical providers should assess multiple symptoms including abdominal pain, psychological distress and fatigue in patients with IBS (Lackner et al., 2013). Nurses in gastroenterological practice need to be cognizant of the impact of abdominal pain on other symptoms such as fatigue that combined result in reduced quality of life and interference with work or school. Clinicians should also assess and manage other factors serve as triggers (e.g., stress, poor sleep) for fatigue in IBS (Asare et al., 2012). Our findings lead to a potential intervention opportunity to manage fatigue. For example, strategies to improve psychological distress by better abdominal pain management may contribute to reduce fatigue in IBS. Additionally, psychological interventions targeting mental and emotional health may improve fatigue for IBS patients with co-occurring pain and psychological distress.

Conclusion

Fatigue is a common extra-intestinal symptom reported by women with IBS, and is temporally linked to report of abdominal pain. Some of the effect of abdominal pain on fatigue is partially mediated by psychological distress, but abdominal pain has a direct effect on fatigue as well. Our findings emphasize the need for clinicians to address abdominal pain, and psychological distress when managing fatigue in patients with IBS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows. CJH was involved in all part of this manuscript as a first author as well as a corresponding author: designed the research questions, aims introduction, methods, data analyses, results and discussion part. MJ and MH guided overall study aims, study design and methods and discussion writing, and reviewed all manuscript works.

Funding:

First author, CJH, is under the training grant: The first author, CJH, received post-doctoral trainee grant by the NIH National Library of Medicine (NLM) Training Program in Biomedical and Health Informatics Grant Nr. T15LM007442; and National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Training Grant Nr. 5T32CA092408-17.

This was not an industry supported study.

The all three authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article (secondary data analysis).

Parent studies were supported by National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, USA (Grant Nr. NR004142, and P30 NR04001).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Claire J. Han, Email: jyh0908@uw.edu.

Monica E. Jarrett, Email: jarrett@uw.edu.

Margaret M. Heitkemper, Email: heit@uw.edu.

References

- Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2016;9:211–217. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S104807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asare F, Bjorkman I, Wilpart K, Ung EJ, Bjornsson E, Törnblom H, Simren M. Factors of importance for fatigue in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):S-300. [Google Scholar]

- Bai T, Xia J, Jiang Y, Cao H, Zhao Y, Zhang L, … Hou X. Comparison of the Rome IV and Rome III criteria for IBS diagnosis: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017;32(5):1018–1025. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JA. Mediator and moderator variables in nursing research: Conceptual and statistical differences. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23(5):415–420. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200010)23:5<415::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan DT, Cain K, Heitkemper M, Burr R, Vitiello MV, Zia J, Jarrett M. Sleep measures predict next-day symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014;10(9):1003. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Rosen S, Hertig VL, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in gastrointestinal, psychological, and somatic symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 2009;54(7):1542–1549. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremon C, Carini G, Wang B, Vasina V, Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, … Corinaldesi R. Intestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron activation, and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106(7):1290–1298. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1262–1279. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. The Rome II Modular Questionnaire: In The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon; 2000. pp. 670–688. [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Journal of Gastrointestinal & Liver Diseases. 2006;15(3):237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, Diamant N, Hu YJ, Bangdiwala SI, Jia H. What determines severity among patients with painful functional bowel disorders? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95(4):974–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, Bolino C, Pintos–Sanchez MI, Moayyedi P. Validation of the Rome III criteria for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in secondary care. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1262–1270. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandemark A, Jakobsson Ung E, Tornblom H, Simren M, Jakobsson S. Fatigue: a distressing symptom for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2017;29(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne AM, Chang L, Mayer EA. Racial differences in the impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2004;38(9):782–789. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000140190.65405.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie E, Creed F, Fernandes L, Ratcliffe J, Van Der Jagt J, Martin J, … Thompson D. Cluster analysis of symptoms and health seeking behaviour differentiates subgroups of patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52(11):1616–1622. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CJ, Yang GS. Fatigue in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of pooled frequency and severity of fatigue. Asian Nursing Research. 2016;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Shulman R, Burr R, Poppe A, Jarrett M. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome based on abdominal pain/discomfort severity and bowel pattern. Digestuve Diseases & Science. 2011;56(7):2050–2058. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertig VL, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Heitkemper MM. Daily stress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nursing Research. 2007;56(6):399–406. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299855.60053.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2004;10(4):299–309. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Barney PG, Burr RL, Naliboff BD, Shulman R, … Heitkemper MM. Balance of autonomic nervous system predicts who benefits from a self-management intervention program for irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2016;22(1):102–111. doi: 10.5056/jnm15067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Burr RL, Hertig VL, Rosen SN, Heitkemper MM. Comprehensive self-management for irritable bowel syndrome: randomized trial of in-person vs. combined in-person and telephone sessions. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(12):3004–3014. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Tuftin M, Walker EA, Bond EF, Levy RL. The relationship between psychological distress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nursing Research. 1998;47(3):154–161. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett ME, Shulman RJ, Cain KC, Deechakawan W, Smith LT, Richebé P, … Heitkemper MM. Conditioned pain modulation in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Biological Research for Nursing. 2014;16(4):368–377. doi: 10.1177/1099800413520486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karling P, Danielsson Å, Wikgren M, Söderström I, Del-Favero J, Adolfsson R, Norrback KF. The relationship between the val158met catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism and irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, DiMuro J, Keefer L, Brenner DM. Psychosocial predictors of self-reported fatigue in patients with moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2013;51(6):323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmark-Høyvik H, Reinertsen KV, Loge JH, Kristensen VN, Dumeaux V, Fosså SD, … Edvardsen H. The genetics and epigenetics of fatigue. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2010;2(5):456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2012;10(7):712–721. e714. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Viñas JJ, Quigley EM. Immune response in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review of systemic and mucosal inflammatory mediators. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2016;17(9):572–581. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaka MM. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal. 2012;24(3):69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy-Szakal D, Williams BL, Mishra N, Che X, Lee B, Bateman L, … Peterson DL. Fecal metagenomic profiles in subgroups of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HS, Seo WS. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the correlates of cancer-related fatigue. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2011;8(4):191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowska T, Chalder T, Hirsch SR, Wallace P, Wright DJM, Wessely SC. Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress. British Medical Jounal. 1994;308(6931):763–766. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Zheng X. Multilevel structural equation modeling. In: Lee S-Y, editor. Handbook of latent variable and related models. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman RJ, Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Broussard EK, Heitkemper MM. Associations among gut permeability, inflammatory markers, and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;49(11):1467–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0919-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simren M, Svedlund J, Posserud I, Bjornsson ES, Abrahamsson H. Predictors of subjective fatigue in chronic gastrointestinal disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;28(5):638–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G, Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Walker L, Whitehead WE. Rome III diagnostic questionnaire for the adult functional GI disorders. 2006 Retrieved June 5, 2015from http://www.romecriteria.org/pdfs/AdultFunctGIQ.pdf.

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winger A, Kvarstein G, Wyller VB, Sulheim D, Fagermoen E, Småstuen MC, Helseth S. Pain and pressure pain thresholds in adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal. 2014;4(10):e005920. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.