Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition with substantial burden and limited treatment options for adolescents with moderate-to-severe disease. Significantly more patients treated with dupilumab vs. placebo achieved Investigator’s Global Assessment 0/1 at week 16.

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess the impact of dupilumab treatment vs. placebo on the achievement of clinically meaningful improvements in atopic dermatitis signs, symptoms and quality of life.

Methods

R668-AD-1526 LIBERTY AD ADOL was a randomized, double-blinded, parallel-group, phase III clinical trial. Two hundred and fifty-one adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis received dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (q4w; n = 84), dupilumab 200 or 300 mg every 2 weeks (q2w; n = 82), or placebo (n = 85). A post-hoc subgroup analysis was performed on 214 patients with Investigator’s Global Assessment > 1 at week 16. Measures of atopic dermatitis signs, symptoms, and quality of life were assessed. Clinically meaningful improvement in one or more of three domains of signs, symptoms, and quality of life was defined as an improvement of ≥ 50% in Eczema Area and Severity Index, ≥ 3 points in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale, or ≥ 6 points in the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index from baseline.

Results

Of patients receiving dupilumab q2w, 80.5% [66/82] experienced clinically meaningful improvements in atopic dermatitis signs, symptoms, or quality of life at week 16 (vs. placebo, 20/85 [23.5%], difference 57.0% [95% confidence interval 44.5–69.4]; q4w vs. placebo, 53/84 [63.1%], difference 39.6% [95% confidence interval 25.9–53.3]; both p < 0.0001). Results were similar in adolescents with Investigator’s Global Assessment > 1 at week 16 (q2w, 46/62 [74.2%] vs. placebo, 18/83 [21.7%], difference 52.5% [95% confidence interval 38.5–66.6]; q4w, 38/69 [55.1%] vs. placebo, difference 33.4% [95% confidence interval 18.7–48.1]; both p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Dupilumab provided clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and quality of life in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis among patients with Investigator’s Global Assessment > 1 at week 16. Treatment responses should be interpreted in the context of such clinically relevant patient-reported outcome measures.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT03054428.

Video abstract

Adolescents with atopic dermatitis: does dupilumab improve their signs, symptoms, and quality of life? (MP4 212916 kb)

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40257-019-00478-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| In a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial, adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) receiving dupilumab showed significant improvements in clinical signs as demonstrated by Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score reflecting clear (0)/almost clear (1) skin at week 16; however, the IGA may not comprehensively capture the impact of AD, including patient-reported symptoms and health-related quality of life. |

| The majority of adolescents treated with dupilumab showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs, symptoms (including pruritus, sleep loss), and quality of life compared with placebo-treated patients, even among those not achieving IGA 0/1. |

| The IGA response should be interpreted within the context of additional outcome measures that more comprehensively characterize changes with treatment in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life in adolescents with moderate-to-severe disease. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by eczematous lesions and often intense pruritus and atopic and non-atopic comorbidities [1–4]. The burden of moderate-to-severe AD on adolescents and their caregivers is substantial, particularly pruritus associated with chronic sleep disturbance, which can profoundly affect daily functioning, quality of life (QoL), social interactions, and psychosocial health [5–11]. Adolescents commonly have persistent disease that extends into adulthood [12], indicating that the underlying pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of AD are similar in adolescents and adults [13].

Until recently, the only approved treatment options for adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD were topical agents and systemic corticosteroids, treatments recommended by clinical practice guidelines only in limited circumstances [14, 15]. Most treatments for adolescents are used off label, including systemic immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, with unclear long-term risks and benefits [16–18].

Dupilumab, a fully human VelocImmune®-derived [19, 20] monoclonal antibody, blocks the shared receptor unit for interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, thus inhibiting signaling of both cytokines. In clinical trials, dupilumab demonstrated significant efficacy in improving signs and symptoms of AD, symptoms of anxiety/depression, and QoL in adults with moderate-to-severe AD, with a favorable safety profile [21–24]. Dupilumab is approved for subcutaneous administration for the treatment of patients aged ≥ 12 years in the USA with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable [25], for the treatment of adult patients with AD not adequately controlled with existing therapies in Japan, and for use in patients aged ≥ 12 years with moderate-to-severe AD who are candidates for systemic therapy in the European Union [26]. Dupilumab is also approved by the US Food and Drug Administration [25] as an add-on maintenance treatment in patients aged ≥ 12 years with moderate-to-severe asthma and an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma regardless of eosinophilic phenotype [27–29].

Adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD treated with dupilumab showed significant improvements in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (R668-AD-1526 LIBERTY AD ADOL, NCT03054428) [30]. Both co-primary endpoints of the trial were achieved in more patients receiving dupilumab than in those who received placebo. Those endpoints were a score of 0 (clear skin) or 1 (almost clear skin) and ≥ 2 points improvement from baseline in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score (p < 0.0001) and at least 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75; p < 0.0001) at week 16.

The IGA is useful because of its simplicity, precedence, and endorsement by regulatory authorities, but is limited strictly to cutaneous signs and does not assess the body surface area (BSA) affected or patient-reported symptoms, which have the greatest impact on QoL. Correlations between investigator- and patient-reported outcome measures of disease severity are weak to moderate [31, 32]. For these reasons, a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of AD treatment combines clinician- and patient-reported measures to more broadly assess AD signs, symptoms (e.g., pruritus, sleeplessness), and health-related QoL. Such a definition of treatment response would be more relevant for clinical decision making than one based on IGA alone. Therefore, clinically meaningful improvements are defined here as improvements from baseline of ≥ 50% in EASI [26, 33], ≥ 3 points in the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score [34, 35], or ≥ 6 points in the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) [36], values based on published thresholds of clinically meaningful improvements.

To more thoroughly evaluate the clinical benefit of dupilumab, we report here post-hoc analyses of the proportions of adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who had clinically relevant responses to dupilumab vs. placebo in the LIBERTY AD ADOL trial. We also evaluate the relationship between dupilumab exposure and achievement of these clinically relevant endpoints.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

The design and primary results from the LIBERTY AD ADOL study have been reported previously and are briefly summarized here [30]. LIBERTY AD ADOL was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, parallel-group, phase III study conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committees and the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The protocol is available in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies.

Patients, Randomization, and Masking

Patients aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD not adequately controlled by topical medications or for whom topical therapy was not advisable were eligible to participate. At screening and baseline visits, eligible patients had an IGA score ≥ 3 (out of 4), EASI ≥ 16 (out of 72), Peak Pruritus NRS score ≥ 4 (out of 10), and BSA affected by AD ≥ 10%. Patients were randomly selected to receive dupilumab every 2 weeks (q2w; 200 mg if baseline weight was < 60 kg or 300 mg if baseline weight was ≥ 60 kg) or every 4 weeks (q4w; 300 mg) or placebo q2w for 16 weeks. To maintain blinding, patients in the q4w group received injections q2w, alternating placebo with active treatment. Topical or systemic medications such as non-steroidal immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, or calcineurin inhibitors were prohibited unless required for rescue treatment for intolerable symptoms.

Study Outcomes

The co-primary endpoints of this trial were the proportions of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 (and ≥ 2-point improvement in IGA score) and EASI-75 at week 16 [30]. Here, we report secondary outcomes and post-hoc analyses performed on the full analysis set (FAS) of randomized patients and on a subgroup of patients who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16 (IGA > 1 subgroup).

Clinician- and patient-reported outcomes included changes from baseline to week 16 in EASI, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) total score, BSA affected, Peak Pruritus NRS score, SCORAD pruritus and sleep visual analog scale (VAS) score, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) score, CDLQI, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) total score and scores on the anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) domains.

We compared the proportions of patients who achieved the clinical response thresholds of EASI-50, EASI-75, ≥ 3- or 4-point improvement in the Peak Pruritus NRS score, or ≥ 6-point improvement in the POEM score or CDLQI and of those in each response category of the Patient Global Assessment of Disease Severity (“no symptoms,” “mild symptoms,” “moderate symptoms,” or “severe symptoms”). Clinically meaningful improvement in at least one of the three domains of signs, symptoms, and QoL was defined as EASI-50, ≥ 3-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS score from baseline, ≥ 6-point improvement in POEM score from baseline, or ≥ 6-point improvement in CDLQI from baseline at week 16. Improvement thresholds for EASI [26, 33], Peak Pruritus NRS score [34, 35], POEM score [33, 36], and CDLQI [36] were based on the published minimal clinically important differences in the population of adolescents with AD. We also assessed the proportions of patients with EASI ≤ 7 at week 16, a category that corresponds to mild AD [37], and with CDLQI ≤ 6, a category indicating no or a small impact on QoL [38].

Concentrations of dupilumab at week 16 in the FAS were compared in those who achieved EASI-50 or Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline at week 16 and in those who did not. Serum samples for quantification of functional dupilumab concentrations were analyzed using a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The proportions of patients needing rescue medication were evaluated. Safety outcomes from the LIBERTY AD ADOL trial have been reported previously for the overall population and are summarized here for the safety analysis set and the IGA > 1 post-hoc analysis subgroup [30].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods for the LIBERTY AD ADOL study have been reported previously [30]. The statistical analysis plan is available in the ESM. Binary endpoints were analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test with adjustment for randomization strata (baseline disease severity and weight). Patients with missing values at week 16 or who used rescue medication before week 16 were considered “non-responders” and their data were imputed. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using multiple imputation and analysis of covariance with treatment, with randomization strata and relevant baseline values included in the model. Data from patients using rescue medication were considered “missing” from the time of use and imputed by multiple imputation. Descriptive statistics were used to assess demographic and clinical characteristics. Least-squares mean (with standard error) and percent change from baseline were reported for EASI, SCORAD total and SCORAD pruritus and sleep VAS scores, BSA, Peak Pruritus NRS score, POEM score, CDLQI, and HADS total and HADS-A and HADS-D domain scores. The proportions of patients meeting pre-specified thresholds for other outcomes were reported as number and percentage of total. Patients who withdrew or received rescue medication were counted as “non-responders” from the time of withdrawal or of use of rescue medication. Patients with missing values at week 16 were considered “non-responders” and were combined with patients who did not achieve IGA score 0 or 1 at week 16, to comprise the week 16 IGA > 1 subgroup.

For the comparison of dupilumab concentrations at week 16, logistic regression analysis was conducted when the probability of achieving IGA 0 or 1 was related to the exposure metric, observed Ctrough. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.2 or higher; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

A total of 251 patients in the FAS were randomly selected to receive dupilumab 300 mg q4w (n = 84), dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w (n = 82), or placebo q2w (n = 85) (Fig. S1 of the ESM). The IGA > 1 subgroup (patients who did not achieve IGA 0 or 1 at week 16) consisted of 214 patients of whom 69 received dupilumab 300 mg q4w, 62 dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w, and 83 placebo (Fig. S1 of the ESM). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the FAS and the IGA > 1 subgroup (Table 1) were generally similar across treatment groups. Compared with the overall FAS population, the IGA > 1 subgroup had a greater proportion of patients with indicators of more severe disease at baseline as reflected by IGA score, EASI, SCORAD, BSA affected by AD, and CDLQI. Nearly all patients across treatment groups had at least one comorbid allergic condition (FAS: placebo 78/85 [92%], dupilumab q4w 74/84 [88%], and q2w 79/82 [96%]; IGA > 1 subgroup: placebo 76/83 [92%], dupilumab q4w 61/69 [88%], and q2w 61/62 [98%]), mostly asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or food allergy.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the full analysis set and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) > 1 subgroup

| Full analysis set (n = 251) | IGA > 1 subgroup (n = 214) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 85) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w (n = 84) |

Dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w (n = 82) |

Placebo (n = 83) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w (n = 69) |

Dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w (n = 62) |

|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 14.5 (1.8) | 14.4 (1.6) | 14.5 (1.7) | 14.4 (1.8) | 14.3 (1.5) | 14.6 (1.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 53 (62) | 52 (62) | 43 (52) | 51 (61) | 44 (64) | 30 (48) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 64.4 (21.5) | 65.8 (20.1) | 65.6 (24.5) | 64.0 (21.1) | 66.3 (20.5) | 65.9 (20.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 23.9 (6.0) | 24.1 (5.9) | 24.9 (7.9) | 23.9 (6.1) | 24.1 (5.9) | 24.9 (6.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 48 (56) | 55 (65) | 54 (66) | 47 (57) | 44 (64) | 41 (66) |

| Black or African American | 15 (18) | 8 (10) | 7 (9) | 14 (17) | 6 (9) | 3 (5) |

| Asian | 13 (15) | 13 (15) | 12 (15) | 13 (16) | 11 (16) | 10 (16) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 6 (7) | 5 (6) | 5 (6) | 6 (7) | 5 (7) | 5 (8) |

| Not reported | 3 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 13 (15) | 20 (24) | 13 (16) | 13 (16) | 14 (20) | 11 (18) |

| Duration of AD, mean (SD), years | 12.3 (3.4) | 11.9 (3.2) | 12.5 (3.0) | 12.2 (3.5) | 12.1 (3.1) | 12.5 (3.0) |

| History of atopic comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 concurrent allergic condition excluding AD | 78 (92) | 74 (88) | 79 (96) | 76 (92) | 61 (88) | 61 (98) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis (keratoconjunctivitis) | 16 (19) | 21 (25) | 20 (24) | 15 (18) | 20 (29) | 15 (24) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 57 (67) | 49 (58) | 59 (72) | 55 (66) | 38 (55) | 44 (71) |

| Asthma | 46 (54) | 43 (51) | 46 (56) | 44 (53) | 37 (54) | 34 (55) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 7 (8) | 6 (7) | 6 (7) | 7 (8) | 5 (7) | 4 (6) |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Food allergy | 48 (57) | 53 (63) | 52 (63) | 46 (55) | 43 (62) | 42 (68) |

| Hives | 22 (26) | 28 (33) | 22 (27) | 22 (27) | 23 (33) | 20 (32) |

| Nasal polyps | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Other allergiesa | 62 (73) | 54 (64) | 58 (71) | 61 (73) | 49 (71) | 46 (74) |

| Patients receiving prior systemic medications for AD, n (%) | 33 (39) | 38 (45) | 35 (43) | 32 (39) | 31 (45) | 27 (44) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 21 (25) | 27 (32) | 21 (26) | 20 (24) | 20 (29) | 15 (24) |

| Systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants | 17 (20) | 15 (18) | 20 (24) | 17 (20) | 15 (22) | 16 (26) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Cyclosporine | 12 (14) | 6 (7) | 14 (17) | 12 (14) | 6 (9) | 13 (21) |

| Methotrexate | 6 (7) | 10 (12) | 10 (12) | 6 (7) | 10 (14) | 7 (11) |

| Mycophenolate | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Biomarkers, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 286.0 (99.1) | 300.9 (101.6) | 295.4 (102.5) | 286.4 (100.2) | 315.3 (101.8) | 311.3 (109.0) |

| Total IgE, kU/L | 9378.9 (13,797.2) | 7032.1 (9215.0) | 7254.5 (9457.1) | 9427.7 (13,929.7) | 7787.8 (9625.9) | 8371.3 (9967.8) |

| TARC, pg/mL | 6565.8 (11,296.5) | 5781.9 (8369.0) | 6102.3 (9159.6) | 6676.7 (11,410.6) | 6349.4 (8796.9) | 7272.2 (10,097.1) |

| Disease severity, mean (SD) unless otherwise noted | ||||||

| IGA score 4, n (%) | 46 (54) | 46 (55) | 43 (52) | 45 (54) | 44 (64) | 35 (56) |

| EASI (0–72) | 35.5 (14.0) | 35.8 (14.8) | 35.3 (13.8) | 35.4 (13.9) | 37.8 (14.7) | 37.5 (14.4) |

| SCORAD total score (0–103) | 70.4 (13.3) | 69.8 (14.1) | 70.6 (13.9) | 70.3 (13.3) | 71.7 (14.0) | 72.5 (14.0) |

| BSA affected by AD (%) | 56.4 (24.1) | 56.9 (23.5) | 56.0 (21.4) | 56.4 (24.4) | 58.6 (23.5) | 59.4 (22.4) |

| Peak Pruritus NRS score (0–10) | 7.7 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.8) | 7.5 (1.5) | 7.7 (1.6) | 7.8 (1.7) | 7.6 (1.4) |

| SCORAD—Pruritus VAS score (0–10) | 7.7 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.9) | 7.9 (1.7) | 7.7 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.9) | 8.0 (1.5) |

| SCORAD—Sleep VAS score (0–10) | 5.6 (3.1) | 5.9 (3.2) | 5.4 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.1) | 6.3 (3.1) | 5.8 (3.4) |

| POEM score (0–28) | 21.1 (5.4) | 21.1 (5.5) | 21.0 (5.0) | 21.0 (5.4) | 21.6 (5.6) | 21.5 (5.1) |

| CDLQI (0–30) | 13.1 (6.7) | 14.8 (7.4) | 13.0 (6.2) | 13.0 (6.7) | 15.4 (7.5) | 14.3 (6.1) |

| HADS total score (0–42) | 11.6 (7.8) | 13.3 (8.2) | 12.6 (8.0) | 11.7 (7.8) | 13.5 (8.2) | 12.9 (8.5) |

| HADS-A score (0–21) | 7.4 (4.4) | 8.0 (4.9) | 8.1 (4.6) | 7.4 (4.4) | 8.1 (4.9) | 8.2 (4.8) |

| HADS-D score (0–21) | 4.3 (3.9) | 5.2 (4.2) | 4.4 (4.2) | 4.3 (3.9) | 5.3 (4.2) | 4.7 (4.4) |

| PGADS “no” or “mild” symptoms, n (%) | 10 (12) | 5 (6) | 8 (10) | 10 (12) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) |

| PGADS “moderate” symptoms, n (%) | 20 (23.5) | 32 (38) | 22 (27) | 20 (24) | 23 (33) | 16 (26) |

| PGADS “severe” symptoms, n (%) | 30 (35) | 26 (31) | 32 (39) | 28 (34) | 23 (33) | 27 (44) |

| PGADS “very severe” symptoms, n (%) | 25 (29) | 21 (25) | 20 (24) | 25 (30) | 21 (30) | 15 (24) |

FAS data also reported by Simpson et al. (2019) [30]

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FAS full analysis set, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Anxiety, HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Depression, IgE immunoglobulin E, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, PGADS Patient Global Assessment of Disease Severity, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation, TARC thymus and activation-regulated chemokine, VAS visual analog scale

aIncludes allergies to medications, animals, plants, mold, and dust mites

Clinician- and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Full Analysis Set of Randomized Patients

A significantly greater proportion of patients receiving dupilumab achieved the co-primary endpoints of IGA score 0 or 1 (and ≥ 2 points improvement) and EASI-75 at week 16, compared with those receiving placebo, as reported previously [30]. Patients receiving dupilumab had statistically significant improvements from baseline to week 16, vs. placebo, in EASI, SCORAD total score, Peak Pruritus NRS score, SCORAD pruritus VAS score, SCORAD sleep VAS score, POEM score, and CDLQI (Table 2) and significantly more of them also achieved EASI ≤ 7 or CDLQI ≤ 6 by week 16 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes at week 16 in patients in the full analysis set and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) > 1 subgroup

| Full analysis set (n = 251) | IGA > 1 subgroup (n = 214) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 85) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w (n = 84) |

Dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w (n = 82) | Placebo (n = 83) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w (n = 69) |

Dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w (n = 62) | |

| EASI LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 9.2 (1.8) |

− 22.6 (1.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 22.2 (1.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 8.8 (1.9) |

− 21.9 (1.7) p < 0.0001 |

− 19.7 (1.6) p < 0.0001 |

| EASI LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) | − 23.6 (5.5) |

− 64.8 (4.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 65.9 (4.0) p < 0.0001 |

−20.7 (5.6) |

− 58.4 (5.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 55.0 (4.9) p < 0.0001 |

| EASI-50, n (%) | 11 (13) |

46 (55) p < 0.0001 |

50 (61) p < 0.0001 |

9 (11) |

31 (45) p < 0.0001 |

30 (48) p < 0.0001 |

| EASI-75, n (%) | 7 (8) |

32 (38) p < 0.0001 |

34 (41) p < 0.0001 |

5 (6) |

17 (25) p = 0.0013 |

14 (23) p = 0.0047 |

| EASI ≤ 7 at week 16, n (%) | 7 (8) |

28 (33) p < 0.0001 |

34 (41) p < 0.0001 |

5 (6) |

13 (19) p = 0.0049 |

14 (23) p = 0.0034 |

| SCORAD total score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 13.2 (2.5) |

− 33.2 (2.2) p < 0.0001 |

− 35.8 (2.2) p < 0.0001 |

− 12.4 (2.4) |

− 29.0 (2.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 29.9 (2.4) p < 0.0001 |

| SCORAD total score LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) | − 17.6 (3.8) |

− 47.5 (3.2) p < 0.0001 |

− 51.6 (3.2) p < 0.0001 |

− 15.8 (3.5) |

−39.4 (3.4) p < 0.0001 |

− 41.3 (3.5) p < 0.0001 |

| BSA LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 11.7 (2.7) |

−33.4 (2.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 30.1 (2.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 10.8 (2.7) |

− 31.3 (2.7) p < 0.0001 |

− 24.5 (2.8) p = 0.0002 |

| Peak Pruritus NRS score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 1.5 (0.3) |

− 3.4 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 3.7 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 1.5 (0.3) |

− 3.2 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 3.5 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

| Peak Pruritus NRS score LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) | − 19.0 (4.1) |

− 45.5 (3.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 47.9 (3.4) p < 0.0001 |

− 17.4 (4.2) |

− 41.2 (4.1) p < 0.0001 |

− 44.2 (4.0) p < 0.0001 |

| Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) | 8/85 (9) |

32/83 (39) p < 0.0001 |

40/82 (49) p < 0.0001 |

6/83 (7.2) |

21/69 (30.4) p = 0.0001 |

27/62 (43.5) p < 0.0001 |

| Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 4-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) | 4/84 (5) |

22/83 (27) p = 0.0001 |

30/82 (37) p < 0.0001 |

3/82 (4) |

13/69 (19) p = 0.0025 |

21/62 (34) p < 0.0001 |

| SCORAD—Pruritus VAS score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 2.1 (0.4) |

− 4.0 (0.3) p = 0.0002 |

− 4.4 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 2.0 (0.4) |

− 3.4 (0.4) p = 0.0124 |

− 3.8 (0.4) p = 0.0012 |

| SCORAD—Sleep VAS score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 1.1 (0.4) |

− 3.0 (0.3) p = 0.0001 |

− 3.6 (0.3) p < 0.0001 |

− 1.2 (0.4) |

− 2.7 (0.4) p = 0.0071 |

− 3.4 (0.4) p < 0.0001 |

| POEM score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 3.8 (1.0) |

− 9.5 (0.9) p < 0.0001 |

− 10.1 (0.8) p < 0.0001 |

− 3.5 (1.0) |

− 8.4 (1.0) p = 0.0005 |

− 8.5 (0.9) p = 0.0001 |

| POEM ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) | 8/84 (10) |

39/84 (46) p < 0.0001 |

52/82 (63) p < 0.0001 |

7/82 (9) |

27/69 (39) p < 0.0001 |

33/62 (53) p < 0.0001 |

| CDLQI LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 5.1 (0.6) |

− 8.8 (0.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 8.5 (0.5) p < 0.0001 |

− 5.6 (0.7) |

− 8.5 (0.6) p = 0.0022 |

− 8.4 (0.6) p = 0.0023 |

| CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) | 15/76 (20) |

42/71 (59) p < 0.0001 |

43/71 (61) p < 0.0001 |

14/74 (19) |

30/59 (51) p = 0.0002 |

32/56 (57) p < 0.0001 |

| CDLQI ≤ 6 at week 16, n/N (%) | 13/73 (18) |

32/69 (46) p = 0.0003 |

36/69 (52) p < 0.0001 |

12/71 (17) |

21/57 (37) p = 0.0104 |

25/56 (45) p = 0.0007 |

| HADS total score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 2.5 (0.8) |

− 5.2 (0.7) p = 0.0133 |

− 3.8 (0.7) p = 0.2203 |

− 2.3 (0.8) |

− 4.2 (0.8) p = 0.0939 |

− 3.7 (0.8) p = 0.2076 |

| HADS-A score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 1.6 (0.5) |

− 2.7 (0.5) p = 0.1229 |

− 2.3 (0.4) p = 0.2980 |

− 1.5 (0.5) |

− 1.9 (0.5) p = 0.5757 |

− 2.2 (0.5) p = 0.3043 |

| HADS-D score LS mean change from baseline (SE) | − 0.8 (0.4) |

− 2.4 (0.4) p = 0.0016 |

− 1.4 (0.3) p = 0.1691 |

− 0.7 (0.4) |

− 2.2 (0.4) p = 0.0076 |

− 1.4 (0.4) p = 0.1892 |

| PGADS “no” or “mild” symptoms, n (%) | 11 (13) |

33 (39) p < 0.0001 |

42 (51) p < 0.0001 |

10 (12) |

19 (28) p = 0.0149 |

26 (42) p < 0.0001 |

| PGADS “moderate” symptoms, n (%) | 9 (11) |

15 (18) p = 0.1703 |

19 (23) p = 0.0304 |

8 (10) | 14 (20) | 15 (24) |

| PGADS “severe” symptoms, n (%) | 10 (12) |

6 (7) p = 0.3007 |

6 (7) p = 0.3070 |

10 (12) | 6 (9) | 6 (10) |

| PGADS “very severe” symptoms, n (%) | 55 (65) | 30 (36) | 15 (18) | 55 (66) | 30 (43) | 15 (24) |

| Use of ≥ 1 rescue medication, n (%) | 50 (59) | 27 (32) | 17 (21) | 50 (60) | 27 (39) | 17 (27) |

| Use of ≥ 1 systemic rescue medication, n (%) | 8 (9) | 0 | 1 (1) | 8 (10) | 0 | 2 (3) |

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FAS full analysis set, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Anxiety, HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Depression, LS least-squares, N number of patients with baseline Peak Pruritus NRS score ≥ 3 or ≥ 4, POEM score ≥ 6, or CDLQI ≥ 6, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, PGADS Patient Global Assessment of Disease Severity, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SE standard error, TARC thymus and activation-regulated chemokine, VAS visual analog scale

FAS data of the pre-specified endpoints also reported by Simpson et al. (2019) [30]

For PGADS, values after the first rescue treatment were set to censor/missing, and all missing data were imputed to the worst category

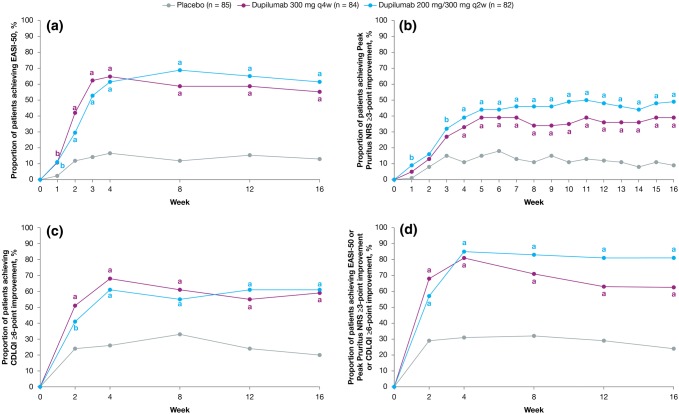

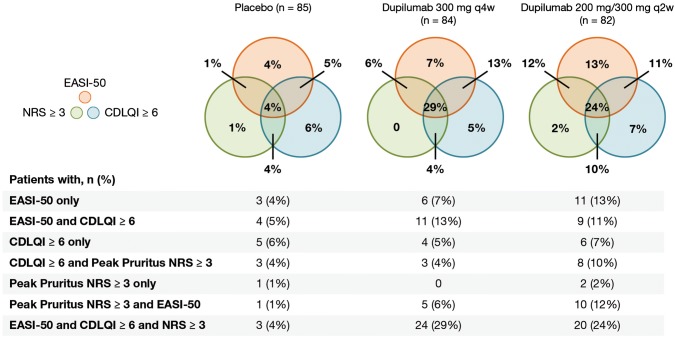

More dupilumab- than placebo-treated patients achieved clinically meaningful improvements in at least one of the three domains of signs (EASI-50), symptoms (Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline), and QoL (CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline) throughout the study (Fig. 1). More patients receiving dupilumab experienced clinically meaningful improvements from baseline in AD signs, symptoms, or QoL at week 16, with q2w numerically superior to q4w (placebo 20/85 [23.5%], dupilumab q4w 53/84 [63.1%], difference 39.6% [95% confidence interval 25.9–53.3]; q2w 66/82 [80.5%], difference 57.0% [95% confidence interval 44.5–69.4]; both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1d). Clinically meaningful improvement in all three domains at week 16 was achieved in 24% of the dupilumab q2w group and in 29% of the dupilumab q4w group; 33% of the dupilumab q2w and 23% of the dupilumab q4w group had improvement in two of the three domains (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2 of the ESM). Dupilumab-treated patients had achieved clinically meaningful response thresholds by the earliest measured time point for EASI-50 (week 1) and CDLQI ≥ 6 (week 2) and by week 3 in the q2w group for Peak Pruritus NRS score ≥ 3 (Fig. 1). The q2w regimen was numerically superior to the q4w regimen for individual EASI-50 and Peak Pruritus NRS responses; CDLQI responses were similar with the two regimens. Mean percentage changes from baseline across outcomes for signs, symptoms, and QoL at each study visit, as well as the number of patients achieving ≥ 6-points improvement in POEM score, are provided in Fig. S3 of the ESM [30]. Baseline and week 16 photographs of two patients provide a visual representation of the clinical changes in AD that can be achieved with dupilumab treatment despite not reaching an IGA score of 0 or 1 (Fig. S4 of the ESM).

Fig. 1.

Proportions of patients in the full analysis set (FAS) who achieved clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and quality of life as defined by a 50% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-50), b Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline, c Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, and d EASI-50 or Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline. ap < 0.01 vs. placebo, bp < 0.05 vs. placebo, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks

Fig. 2.

Proportions of patients in the full analysis set (FAS) who achieved clinically relevant thresholds for improvements in signs, symptoms, and/or quality of life (defined as 50% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI-50] or ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score or ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline in Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index [CDLQI]) at week 16. q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks

Median dupilumab concentrations at week 16 were higher by a factor of 3 in patients who achieved EASI-50 or Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline at week 16 than in those who did not (approximately 40 mg/L vs. 15 mg/L) (Fig. S5 of the ESM). In patients who received dupilumab 200 or 300 mg q2w, median dupilumab concentrations were similar regardless of whether at least one clinically meaningful response was achieved at week 16. In patients who received the 300 mg q4w regimen, median dupilumab concentrations were lower in those without at least one clinically meaningful response at week 16 (Fig. S5b of the EMS). Logistic regression showed a monotonically increasing relationship between the probability of achieving at least one clinically meaningful response at week 16 and dupilumab trough concentration at week 16 (Fig. S5c of the ESM).

Evaluation of Clinically Meaningful Improvements in the Investigator’s Global Assessment > 1 Subgroup: A Post-hoc Analysis

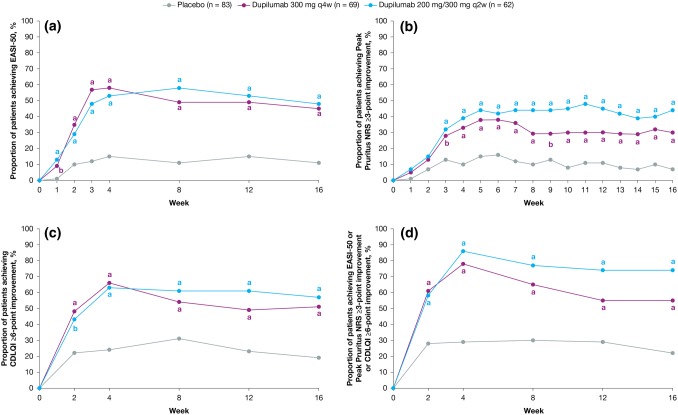

As with the FAS, patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup receiving dupilumab showed significant improvements from baseline to week 16, vs. placebo, in EASI, SCORAD total score, BSA, Peak Pruritus NRS score, SCORAD pruritus VAS score, SCORAD sleep VAS score, POEM score, and CDLQI (Table 2; Fig. 3, and Figs. S6 and S7 of the ESM). A greater proportion of patients with IGA > 1 who received dupilumab experienced clinically meaningful improvements from baseline in AD signs, symptoms, or QoL at week 16; q2w group improvements were numerically superior to those in the q4w group (placebo 18/83 [21.7%], dupilumab q4w 38/69 [55.1%], difference 33.4% [95% confidence interval 18.7–48.1]; q2w 46/62 [74.2%], difference 52.5% [95% confidence interval 38.5–66.6]; both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3d, Fig. S8 of the ESM). As in the FAS, more dupilumab- than placebo-treated patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup achieved clinical response thresholds by the earliest weekly time points measured, for EASI-50 (week 1), CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement (week 2), and Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement (week 3) (Fig. 3). The q2w regimen was numerically superior to the q4w regimen for each of these individual endpoints.

Fig. 3.

Proportions of patients in the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) > 1 subgroup who achieved clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and quality of life as defined by a 50% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-50), b Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline, c Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, and d EASI-50 or Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline. ap < 0.01 vs. placebo, bp < 0.05 vs. placebo, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks

Rescue Medication Use and Adverse Events

Fewer patients receiving dupilumab needed rescue medication for intolerable symptoms than did those receiving placebo in both the FAS and the IGA > 1 subgroup (Table 2). Corticosteroids (groups II–IV) were the most frequently used rescue medication in all treatment groups. As reported, dupilumab had an acceptable safety profile in this adolescent patient population [30]. Safety outcomes in patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup were comparable to those in the overall study population (Table S1 of the ESM). No new safety signals were observed, and safety findings were similar to those observed in dupilumab trials in adults with moderate-to-severe AD [21, 22].

Discussion

Adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who received dupilumab experienced significant and clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and QoL during 16 weeks of treatment, compared with those who received placebo. Patients in the FAS and the IGA > 1 subgroup had statistically significant improvements from baseline (nominal p < 0.05) as early as 1–2 weeks in EASI, SCORAD score, BSA affected, itch (Peak Pruritus NRS and SCORAD pruritus VAS scores), SCORAD sleep VAS score, POEM score, CDLQI, and the Patient Global Assessment of Disease Severity category; they also experienced less breakthrough disease, as assessed by the use of rescue medication for intolerable symptoms, compared with patients who received placebo. More dupilumab-treated patients in both analysis populations had significant improvements in several outcome measures with pre-specified thresholds for clinical importance, including EASI-50 [26, 33] and EASI-75, ≥ 3-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS score [34, 35], and ≥ 6-point improvement in both POEM score [33, 36] and CDLQI [36]. Significantly more dupilumab- than placebo-treated patients in the FAS and IGA > 1 subgroup had an absolute EASI ≤ 7 or CDLQI ≤ 6 at week 16, indicating that they had, at worst, mild disease by the end of treatment [37, 38]. Together, these responses demonstrate clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and QoL in adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD treated with dupilumab vs. placebo. In the overall population and in the IGA > 1 subgroup, the q2w regimen was numerically superior to the q4w regimen in proportions of patients achieving EASI-50, Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline, or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline at week 16. The q2w regimen was also numerically superior for each of these individual endpoints, except for the CDLQI response in the overall population, in which the responses were similar for both regimens. For continuous endpoints, the q2w and q4w regimens were similar.

The response to dupilumab treatment observed in adolescents with AD is comparable to that observed in adults [21, 22, 30], a finding consistent with the type 2-driven pathophysiology of AD at various ages [13] and clinical presentation of AD in young children and adults.

Because the signs and symptoms of AD are multidimensional, no single instrument captures the full burden of disease and benefit of treatment. The IGA was used for the primary endpoint of the LIBERTY AD ADOL trial because it provides an easy and accepted means to score disease severity; however, the IGA may not account for the multidimensional impact of treatment on AD signs, symptoms, and QoL in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Therefore, simply assessing the proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 after treatment may underestimate the holistic benefits of systemic therapy for moderate-to-severe AD, as recently demonstrated in adults [39]. As observed in this study, patients receiving dupilumab monotherapy who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16 nonetheless experienced clinically meaningful improvements in signs, symptoms, and QoL. Atopic dermatitis is a multidimensional disease and patients may have a response in one or more of these three domains, as demonstrated in Figs. 1 and 3 (percentages of patients having improvement in one or more of these domains); note that most dupilumab-treated patients had a response in at least one domain.

Generally, adolescents achieving EASI-50 or having a Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline at week 16 had higher median concentrations of dupilumab than did those who did not achieve at least one clinically meaningful response. However, when stratified by dosing regimen, the dupilumab concentration profile was similar in patients who did and did not achieve at least one clinically meaningful response to the dupilumab 200- or 300-mg q2w regimen. These findings suggest that the lack of response was not due to drug exposure but to pharmacodynamic or biologic factors. With the 300-mg q4w regimen, median dupilumab concentrations were lower in patients who did not achieve at least one clinically meaningful response at week 16.

This report of secondary and post-hoc analyses has limitations. Some outcomes reported here were not pre-specified (i.e., the analyses were not planned before initiation of the study), including the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline in POEM score or CDLQI and the proportions of patients with EASI ≤ 7 and CDLQI ≤ 6. Changes from baseline to week 16 according to SCORAD pruritus and sleep VAS scores and the HADS-A and HADS-D domain scores were also not pre-specified outcomes. Although not initially planned, post-hoc analyses, along with the pre-specified endpoint analyses, provide a more complete picture of the effect of dupilumab on signs, symptoms, and QoL. The small number of patients available in some analytic subsets (e.g., of the individual clinically relevant endpoints) potentially limits the interpretability of their findings. Finally, the ability of randomization to even out inherent variability between groups was influenced by the post-hoc subgroup analysis, and inherent variability can potentially compromise the comparability of treatment arms and confound efficacy assessments.

Conclusions

Adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD treated with dupilumab experienced statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs, symptoms (including pruritus, sleep loss), and QoL at week 16, compared with placebo-treated patients. The q2w regimen was numerically superior to the q4w regimen in proportions of patients achieving EASI-50 or having a Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline or a CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline at week 16. Findings were similar in the subset of adolescents who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16, suggesting that the IGA response should be interpreted within the context of other outcome measures that more comprehensively characterize changes with treatment in AD signs, symptoms, and QoL in adolescents with moderate-to-severe disease.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the patients and their families for their participation and cooperation in the study. Marthe Vuillet and Ana B. Rossi of Sanofi Genzyme developed the spider gram and rainbow graphics in Fig. S4 of the ESM.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

Open access was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The current research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03054428. The study sponsors participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing/editorial assistance was provided by Carolyn Ellenberger, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Conflict of interest

Amy S. Paller has served as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, AnaptysBio, Asana, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Forte, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Matrisys Bioscience, Menlo Therapeutics, MorphoSys/Galapagos, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi. Ashish Bansal, Zhen Chen, Paola Mina-Osorio, Yufang Lu, Xinyi He, Mohamed Kamal, Neil M. H. Graham, Marcella Ruddy, and Abhijit Gadkari are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Eric L. Simpson served as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Forte, Incyte, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Merck, Menlo Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi Genzyme, and Valeant. Mark Boguniewicz served as an investigator and/or consultant for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Sanofi Genzyme. Andrew Blauvelt served as a consultant and investigator for AbbVie, Aclaris, Akros, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Meiji, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Revance, Sandoz, Sanofi Genzyme, Sienna Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma, Valeant, and Vidac and served as a speaker for Janssen, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi Genzyme. Elaine C. Siegfried served as a principal investigator for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Novan, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, and UCB and as an investigator for Allergan, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Mayne, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Verrica. Emma Guttman-Yassky served as an investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi; as a consultant for AbbVie, Anacor, Asana Biosciences, Daiichi Sankyo, DBV Technologies, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, Kiniksa, Kyowa, LEO Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Realm, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi and received research support from AbbVie, Celgene, Dermira, Galderma, Innovaderm, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi. Thomas Hultsch, Ana B. Rossi, Gianluca Pirozzi, and Laurent Eckert are employees of Sanofi, and own Sanofi stock/stock options.

Ethics approval

LIBERTY AD ADOL was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committees and the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11309645.

Laurent Eckert and Abhijit Gadkari co-last authors.

References

- 1.Johansson EK, Ballardini N, Bergström A, Kull I, Wahlgren CF. Atopic and nonatopic eczema in adolescence: is there a difference? Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:962–968. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrestha S, Miao R, Wang L, Chao J, Yuce H, Wei W. Burden of atopic dermatitis in the United States: analysis of healthcare claims data in the commercial. Medicare and Medi-Cal databases. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1989–2006. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0582-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Margolis DJ, Feldman SR, Qureshi A, Hata T, et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:903–912. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paller A, Jaworski JC, Simpson EL, Boguniewicz M, Russell JJ, Block JK, et al. Major comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: beyond allergic disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:821–838. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci G, Bellini F, Dondi A, Patrizi A, Pession A. Atopic dermatitis in adolescence. Dermatol Rep. 2012;4:e1. doi: 10.4081/dr.2012.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slattery MJ, Essex MJ, Paletz EM, Vanness ER, Infante M, Rogers GM, et al. Depression, anxiety, and dermatologic quality of life in adolescents with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slattery MJ, Essex MJ. Specificity in the association of anxiety, depression, and atopic disorders in a community sample of adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Shin A. Association of atopic dermatitis with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Korea: the 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, Bjertness E, Stern RS. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Investig Dermatol. 2014;134:1847–1854. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marciniak J, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Quality of life of parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:711–714. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang HJ, Hwang S, Ahn Y, Lim DH, Sohn M, Kim JH. Family quality of life among families of children with atopic dermatitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016;6:213–219. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2016.6.4.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortz CG, Andersen KE, Dellgren C, Barington T, Bindslev-Jensen C. Atopic dermatitis from adolescence to adulthood in the TOACS cohort: prevalence, persistence and comorbidities. Allergy. 2015;70:836–845. doi: 10.1111/all.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, Leonard A, Wen HC, Huynh T, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drucker AM, Eyerich K, de Bruin-Weller MS, Thyssen JP, Spuls PI, Irvine AD, et al. Use of systemic corticosteroids for atopic dermatitis: International Eczema Council consensus statement. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:768–775. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Totri CR, Eichenfield LF, Logan K, Proudfoot L, Schmitt J, Lara-Corrales I, et al. Prescribing practices for systemic agents in the treatment of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis in the US and Canada: the PeDRA TREAT survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657–682. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva D, Ansotegui I, Morais-Almeida M. Off-label prescribing for allergic diseases in children. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Yasenchak J, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5147–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, Karow M, Dore AT, Pobursky K, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5153–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387:40–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupixent® (dupilumab). Highlights of prescribing information. US Food and Drug Administration; 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s014lbl.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2019.

- 26.Dupixent® (dupilumab). Summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency; 2019. http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2019/20190506144541/anx_144541_en.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2019.

- 27.Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, Maspero J, Wang L, Zhang B, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting β2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388:31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2486–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, Maspero JF, Castro M, Sher L, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2475–2485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson E, Beck L, Wu R, Eckert L, Ardeleanu M, Graham N, et al. Correlation between clinical and patient-reported outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in a phase 2 clinical trial of dupilumab. Poster presented at the 23rd World Congress of Dermatology; Vancouver; 8–13 June, 2015. Abstract 2981830.

- 32.Yosipovitch G, Eckert L, Chen Z, Ardeleanu M, Shumel B, Plaum S, et al. Correlations of itch with quality of life and signs of atopic dermatitis across dupilumab trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5 Suppl.):S95. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.09.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MM, Lindeboom R, Bos JD, Schmitt J. EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, Eckert L, Abbé A, Nelson L, et al. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:761–769. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yosipovitch G, Guillemin I, Eckert L, Reaney M, Nelson L, Clark M, et al. Validation of the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) in adolescent moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients for use in clinical trials. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(Suppl. 2):S98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson E, de Bruin-Weller M, Eckert L, Whalley D, Guillemin I, Reaney M, et al. Responder threshold for the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) in adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Poster presented at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis Conference; Chicago, IL; 6–7 April, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1353–1357. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waters A, Sandhu D, Beattie P, Ezughah F, Lewis-Jones S. Severity stratification of Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) scores. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(Suppl. 1):121. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Ardeleanu M, Thaçi D, Barbarot S, Bagel J, et al. Dupilumab provides important clinical benefits to patients with atopic dermatitis who do not achieve clear or almost clear skin according to the Investigator’s Global Assessment: a pooled analysis of data from 2 phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:80–87. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.