Abstract

Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked inherited glycosphingolipid metabolism disorder, therefore, heterozygous female FD patients display highly variable clinical symptoms, disease severity, and pathological findings. This makes it very challenging to diagnosing female patients with FD. A 69-year-old Japanese female was introduced to the nephrologist for the evaluation of proteinuria. A renal biopsy was performed. Although the light microscopic examinations revealed that most of the glomeruli showed minor glomerular abnormalities, however, vacuolation was apparently found in the tubular epithelial cells. Immunofluorescence staining for globotriaosylceramide was positively detected in some podocytes and distal tubular epithelial cells. In addition, myelin-like structure (zebra body) was detected by electron microscopy. Pathological findings were most consistent with FD. Consequently, biochemical and genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of female FD. Enzyme replacement therapy was performed in conjunction with renin–angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors and beta-blockers. The patient’s family members received the analysis, and the same DNA missense mutation was detected in the patient’s grandson. The enzyme replacement therapy was introduced to the grandson. The present case showed that renal biopsy can contribute towards a correct diagnosis for FD. Particularly, in female FD patients, careful examination of pathological changes is essential, for example, vacuolation of any type of renal cells may be a clue for the diagnosis.

Keywords: Fabry disease, Renal biopsy, Pathology, Vacuolation, Enzyme replacement therapy

Introduction

Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked inherited glycosphingolipid metabolism disorder caused by the absence or deficient activity of lysosomal α-galactosidase A (GLA) [1]. GLA deficiency causes the accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) in various cells throughout the body [2]. The GLA locus is situated on chromosome X, and is randomly inactivated in the cells of female embryos, resulting in a mosaic of normal and mutant cells in varying proportions [3]. According to the mosaic pattern formed, heterozygous female FD patients display highly variable residual enzyme activity, clinical symptoms, disease severity, and pathological findings.

FD is known to progress more slowly in females than in males; however, recent studies have shown that heterozygous females are at significant risk of vital organ dysfunction, including cardiac disease and end-stage renal disease [4]. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) was approved in Japan in 2004, and has been shown to prevent, stabilize, or slow the progression of organ dysfunction in both male and female FD patients [5]. An appropriate diagnosis is required to initiate ERT promptly in both female and male FD patients, and unfortunately many female patients are undiagnosed due to the diverse heterogeneity of female FD and a lack of awareness among clinicians.

Here, we present the case of a female patient with FD detected by renal biopsy who had been undiagnosed for over 30 years.

Case

A 69-year-old Japanese female was referred to the hospital for the evaluation of proteinuria without hematuria, which had been detected 2 years ago. On admission, the patient was asymptomatic, with a blood pressure of 128/88 mmHg. Review of systems confirmed that the patient did not suffer from neuropathic pain, heat, cold, and exercise intolerance, dermatological manifestations (telangictasias and angiokeratomas), hypohidrosis, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Past medical history included an EKG abnormality at the age of 38 years, with deeply inverted T waves in the II, III, aVF, and V3–V6 leads. The patient was later diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) at the age of 43 years. The HCM etiology was not revealed during the follow-up by cardiologists. She could perform daily activities without significant cardiac symptoms. The patient was also diagnosed with cataracts aged 68 years. The patient was not on any medication. Family history revealed that her mother died of heart failure at the age of 73 years. Laboratory data showed that the patient had a serum creatinine (Cr) level of 0.7 mg/dL and proteinuria of 1.6 g/gCr without hematuria. Other cases of proteinuria have been excluded (Table 1). The patient had normal sized kidneys. We performed a renal biopsy.

Table 1.

Blood and urinary analysis on admission

| Blood analysis | Urinary analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 4510 | /μL | TP | 7.0 | g/dL | pH | 5.5 | |

| RBC | 500 | /μL | Alb | 4.1 | g/dL | Sp.Gr | 1.026 | |

| Hb | 15.8 | g/dL | CRP | 0.1 | mg/dL | Protein | 2 + | |

| Ht | 48.7 | % | Ferritin | 33.0 | ng/mL | Glucose | – | |

| Plt | 109,000 | /μL | Cr | 0.66 | mg/dL | Occult blood | ± | |

| PT | 65.5 | % | B2MG | 2.3 | mg/dL | Hyaline cast | 10–19 | /HPF |

| APTT | 26.5 | s | BUN | 19.8 | mg/dL | Granular cast | 5–9 | /HPF |

| AST | 39 | IU/L | HbA1C | 6.3 | % | Protein | 160.0 | mg/dL |

| ALT | 36 | IU/L | ANA | – | Cr | 101.0 | mg/dL | |

| γGTP | 67 | IU/L | MPO-ANCA | 1.0 | IU/mL | Na | 128.0 | mEq/L |

| T-Bil | 0.59 | mg/dL | PR-3 ANCA | 1.0 | IU/mL | K | 66.0 | mEq/L |

| LDH | 278 | IU/L | Anti-GBM-Ab | 2.0 | IU/mL | Cl | 151.0 | mEq/L |

| Na | 141 | mEq/L | CH50 | 55.7 | U/mL | UN | 1051.0 | mEq/L |

| K | 4.1 | mEq/L | C3 | 111.8 | mg/dL | UA | 92.8 | mEq/L |

| Cl | 103 | mEq/L | C4 | 28.3 | mg/dL | NAG | 2.1 | U/L |

| Ca | 9.7 | mg/dL | IgG | 1429 | mg/dL | B2MG | 10 | μg/L |

| P | 4.1 | mg/dL | IgA | 171 | mg/dL | Mulberry cell | – | |

| Mg | 2.1 | mg/dL | IgM | 59 | mg/dL | |||

| TC | 178 | mg/dL | Anti-ds-DNA-Ab | 10.0 | IU/mL | |||

| TG | 123 | mg/dL | Anti-SS-A Ab | 7.0 | U/mL | |||

| UA | 6.1 | mg/dL | Anti-SS-B Ab | 7.2 | U/mL | |||

WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Ht hematocrit, Plt platelet, PT prothrombin time, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γGTP γguanosine triphosphate, T-Bil total bilirubin, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, UA uric acid, TP total protein, Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein, B2MG beta2-microgrobulin, Cr creatinine, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Hba1c hemoglobin A1c, ANA antinuclear antibody, MPO-ANCA myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3-ANCA proteinase-3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, GBM-Ab glomerular basement membrane antibody, CH50 serum complement level, C3 complement factor 3, C4 complement factor 4, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgM immunoglobulin M, ds-DNA-Ab double stranded-DNA antibody, SS-A Ab Sjögren’s syndrome-A antibody, SS-B Ab Sjögren’s syndrome-B antibody, UN urea nitrogen, NAG N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase

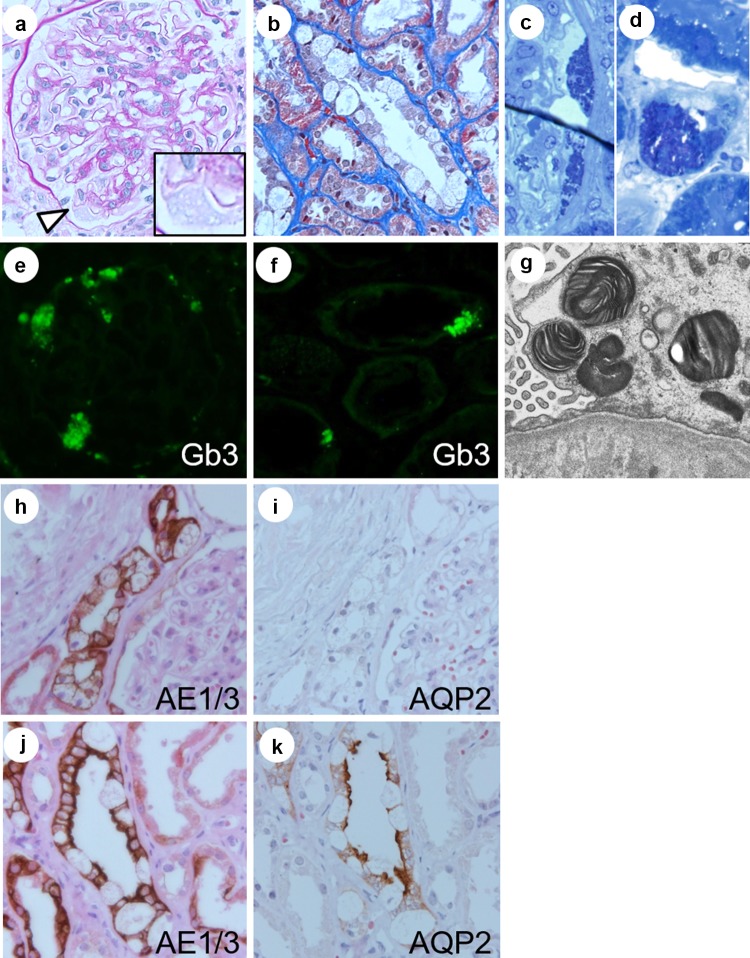

The biopsy specimen contained 22 glomeruli for the light microscopy evaluation, two of which were globally sclerosed. The other glomeruli showed minor glomerular abnormalities. In some glomeruli, the vacuolization of podocytes was slightly evident. Notably, vacuolization was more apparent in tubular epithelial cells, particularly in those of the distal tubules compared to those of the proximal tubules. Immunofluorescence (IF) revealed weak granular positive staining for IgG, IgM, and C3. IF staining was performed for Gb3, which was positively detected in the glomeruli and tubular epithelial cells. Myelin-like structures were detected using electron microscopy. Furthermore, dark blue osmiophilic cells were detected in the podocytes, Bowman’s epithelial cells, and tubular epithelial cells by performing electron microscopy on toluidine blue-stained semi-thin sections. All these pathological findings were most consistent with FD. We also performed immunohistochemistry with AE1/3 and AQP2 to identify distal tubular epithelial cells and principal cells in the collecting ducts, respectively.

Biochemical analysis revealed decreased GLA activity (12 nmol/h/mg protein; normal range 20–80) and increased levels of Lyso-Gb3 in the plasma (20 nmol/L; normal range < 2). Genetic analysis revealed a missense mutation in exon 5, c.[679C>T]. Consequently, the patient was diagnosed with female FD.

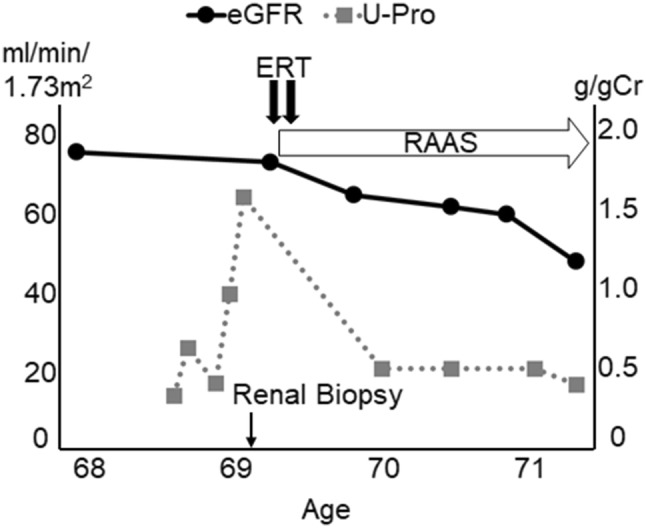

ERT with agalsidase beta 1.0 mg/kg body was performed every 2 weeks in conjunction with renin–angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers. However, the patient developed a severe allergic reaction to ERT and could not continue the treatment. Although an alternative treatment, such as switching to agalsidase-alpha, was considered, the patient refused to continue ERT any longer. During the 2-year follow-up, she was diagnosed with stage G3a chronic kidney disease (CKD) with a Cr of 0.95 mg/dL and proteinuria of 0.4 g/gCr (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Clinical Course. Black circles and gray squares represent the clinical course of eGFR and proteinuria, respectively. eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, ERT enzyme replacement therapy, g/gCr gram/gram creatine, RAAS renin–angiotensin aldosterone system; and U-Pro urine-protein

After the diagnosis was confirmed, the patient revealed additional family history (Figs. 1, 2). The patient’s son (Case III/2) had experienced numbness in his extremities during childhood, which often made it difficult for him to go to school. Without appropriate assessment and treatment, he died due to sudden cardiac arrest at the age of 40 years. An autopsy was also not performed.

Fig. 1.

Family tree. Red color represents patients with Fabry disease, which was confirmed by genetic analysis. The patient’s mother (Case I-1) died of heart failure. The patient’s son (Case III/2) died due to sudden cardiac arrest. The patient’s daughter (Case III/3) was completely asymptomatic. The patient’s grandchild (Case IV/2) had developed neurological pain in his extremities, an early symptom of FD. He started ERT soon after the diagnosis was confirmed

Fig. 2.

Genetic analysis. Genetic analysis was performed on the patient, the patient’s daughter (Case III/3), and the patient’s grandchild (Case IV/2). All showed the same DNA missense mutation in exon 5, c.[679C>T], which confirmed the diagnosis of FD

The patient’s daughter (Case III/3), a 44-year-old female, was completely asymptomatic. Her plasma GLA activity was normal (14 nmol/h/mg protein); however, her plasma Lyso-Gb3 was raised (11 nmol/L), and she was found to possess the same DNA mutation. The patient’s grandchild (Case IV/2), a 12-year-old boy, had developed neurological pain in his extremities. Biochemical analysis revealed a plasma GLA activity of 0.1 nmol/mg protein, a plasma Lyso-Gb3 of 176 nmol/L, and the DNA missense mutation was detected. Following a confirmed diagnosis of FD, Case IV/2 received ERT and has been continuing ERT.

Discussion

Diagnosing female patients with FD is challenging. Mass screening studies of newborn babies have been conducted in which GLA activity was measured to diagnose FD in the early stages of the disease [2]. One of these studies revealed that the incidence of FD was 1/1250 in males and 1/40,840 in females [6]. Conversely, a study for screening patients with symptoms associated with FD reported a much higher prevalence of female FD; 0.1% of those with dialysis, 2.1% of those with premature strokes, and 1.1–11.8% of those with left ventricular hypertrophy [7]. Considering these results, we suggest that clinicians need to focus on conducting appropriate evaluations when female patients first show symptoms related to FD, such as EKG abnormalities, female HCM, or proteinuria of unknown etiology, which may be initial signs of female FD. In our case, proteinuria of unknown etiology combined with suspicious patient history caused the patient to undertake a renal biopsy, which led to a correct diagnosis of female FD.

Renal biopsy can contribute towards a correct diagnosis for heterozygous female FD patients [8]. The accumulated Gb3 inclusions are removed when processing tissue to embed it in paraffin, making the cells appear vacuolated when examined by light microscopy [9]. Valbunea et al. reviewed renal biopsies in four female FD patients. They demonstrated the Gb3 inclusions of podocytes in all patients using semi-thin sections. In other cases, vacuolation was most apparent in podocytes [10–12]. In contrast, in our study, we first observed remarkable vacuolation of tubular cells by light microscopy and found this vacuolation to be more obvious than that of podocytes. This may be because, in female FD patients, each renal cell is a mosaic of varying proportions of normal and mutant genes; therefore, typical podocyte vacuolation is not always observed. We suggest that the careful observation of tubular cells by light microscopy could be a diagnostic clue in female FD patients. Indeed, some studies have reported variable degrees of tubular cell vacuolation according to the tubule segment; distal tubular epithelial cells including those of Henle’s loop and the collecting duct are more commonly and markedly affected than proximal tubular cells [10, 13, 14]. Alroy et al. also reported that intercalated cells were particularly affected in the collecting duct [10]. Consistent with previous studies, in this case, the involvement of podocytes was less evident and distal and collecting tubule cells were more obviously affected. Although the patient did not obviously show symptoms related to distal tubules, such as polyuria or type 1 renal tubular acidosis, according to the immunohistochemistry staining for AE1/3 and AQP2, we showed not only intercalated cells but also principal cells were affected. We suggest that careful pathologic examination, including vacuolation in any type of renal cell, could be an indicator for the correct diagnosis of female FD. To our knowledge, this is the first case report on the immunohistochemical staining of AE1/3 and AQP2 in patients with Fabry disease (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Renal pathology. The renal biopsy samples contained 22 glomeruli for the evaluation of light microscopy, two of which showed global sclerosis. Most of the glomeruli showed mild hypertrophy and minor glomerular abnormalities with mild mesangial expansion (a). Low levels of podocyte vacuolization were detected (white arrowhead in a). Tubular epithelial cell vacuolization occurred predominantly in the distal tubules (b) [a Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain, × 600; b Masson trichrome stain, × 600]. Electron microscopy of toluidine blue-stained semi-thin sections revealed dark blue osmiophilic cells in podocytes, Bowman’s epithelial cells, and distal tubular epithelial cells (c, d). Immunofluorescence staining for Gb3 was positively detected in glomerular and tubular cells (e, f). Electron microscopy revealed myelin-like structures in the podocytes (g). Immunohistochemistry for AE1/3 and AQP2 detected distal tubular epithelial cells and principal cells in collecting tubules, respectively. Serial sections were stained with AE1/3 and AQP2, and counter stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Varying levels of vacuolation were observed in each tubule. In the collecting tubules, both intercalated cells and principal cells showed vacuolation (h–k × 600)

Female FD patients are also at risk of severe vital organ involvement, including kidney and cardiac diseases [4, 15, 16]. According to a Japanese study, female FD patients progressively develop cardiac and renal symptoms with age [17]. The cumulative incidence of left ventricular hypertrophy and proteinuria in female FD patients > 60 years of age was 70% and 56%, respectively. Although the kidney function of female patients has been shown to decline more slowly (− 1.02 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) than that of male patients (− 2.93 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) [18], 1–4% reach end-stage renal disease [4]. The combined use of RAAS inhibitors and ERT has been reported to stabilize kidney function if proteinuria falls below 0.5 g/24 h [19].

In conclusion, we showed a female patient with FD revealed by renal biopsy. Renal biopsy can contribute towards an appropriate diagnosis. In female FD patients, well-characterized podocyte changes might be subtle; therefore, it is essential that every type of renal cell be carefully observed to enable a correct diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Honorary Prof. Nobuaki Yamanaka, Mr. Takashi Arai, Ms. Ms. Mitsue Kataoka, Ms. Kyoko Wakamatsu, Ms. Arimi Ishikawa, and Ms. Naomi Kuwahara for their expert assistance.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

All the procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This case study complied with the Helsinki Declaration standards and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Nippon Medical School Hospital.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brady RO, Gal AE, Bradley RM, Martensson E, Warshaw AL, Laster L. Enzymatic defect in Fabry's disease: ceramidetrihexosidase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1967;27:163–167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196705252762101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garman SC, Garboczi DN. The molecular defect leading to Fabry disease: structure of human alpha-galactosidase. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:319–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, Ortiz A, Banikazemi M, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Sims K, Waldek S, Pastores GM, Lee P, Eng CM, Marodi L, Stanford KE, Breunig F, Wanner C, Warnock DG, Lemay RM, Germain DP. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:112–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Waldek S, Wilcox WR, Whitley CB, McDonald M, Finkel R, Packman S, Bichet DG, Warnock DG, Desnick RJ. Agalsidase-beta therapy for advanced Fabry disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:77–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwu WL, Chien YH, Lee NC, Chiang SC, Dobrovolny R, Huang AC, Yeh HY, Chao MC, Lin SJ, Kitagawa T, Desnick RJ, Hsu LW. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in Taiwan reveals a high incidence of the later-onset GLA mutation c.936+919G%3eA (IVS4+919G%3eA). Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Linthorst GE, Bouwman MG, Wijburg FA, Aerts JM, Poorthuis BJ, Hollak CE. Screening for Fabry disease in high-risk populations: a systematic review. J Med Genet. 2010;47:217–222. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi N, Yokoi S, Kasuno K, Kogami A, Tsukimura T, Togawa T, Saito S, Ohno K, Hara M, Kurosawa H, Hirayama Y, Kurose T, Yokoyama Y, Mikami D, Kimura H, Naiki H, Sakuraba H, Iwano M. A heterozygous female with Fabry disease due to a novel alpha-galactosidase A mutation exhibits a unique synaptopodin distribution in vacuolated podocytes. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83:301–308. doi: 10.5414/CN108317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najafian B, Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Alpers CE. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: Fabry nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:e35–e36. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alroy J, Sabnis S, Kopp JB. Renal pathology in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(Suppl 2):S134–S138. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000016684.07368.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najafian B, Svarstad E, Bostad L, Gubler MC, Tondel C, Whitley C, Mauer M. Progressive podocyte injury and globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) accumulation in young patients with Fabry disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:663–670. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer EG, Moore MJ, Lager DJ. Fabry disease: a morphologic study of 11 cases. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gubler MC, Lenoir G, Grunfeld JP, Ulmann A, Droz D, Habib R. Early renal changes in hemizygous and heterozygous patients with Fabry's disease. Kidney Int. 1978;13:223–235. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogo AB, Bostad L, Svarstad E, Cook WJ, Moll S, Barbey F, Geldenhuys L, West M, Ferluga D, Vujkovac B, Howie AJ, Burns A, Reeve R, Waldek S, Noel LH, Grunfeld JP, Valbuena C, Oliveira JP, Muller J, Breunig F, Zhang X, Warnock DG. Scoring system for renal pathology in Fabry disease: report of the International Study Group of Fabry Nephropathy (ISGFN) Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2010;25:2168–2177. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz A, Oliveira JP, Waldek S, Warnock DG, Cianciaruso B, Wanner C. Nephropathy in males and females with Fabry disease: cross-sectional description of patients before treatment with enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2008;23:1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chimenti C, Pieroni M, Morgante E, Antuzzi D, Russo A, Russo MA, Maseri A, Frustaci A. Prevalence of Fabry disease in female patients with late-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110:1047–1053. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139847.74101.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M, Ohashi T, Sakuma M, Ida H, Eto Y. Clinical manifestations and natural history of Japanese heterozygous females with Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31(Suppl 3):483–487. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiffmann R, Warnock DG, Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Linthorst GE, Packman S, Sorensen SA, Wilcox WR, Desnick RJ. Fabry disease: progression of nephropathy, and prevalence of cardiac and cerebrovascular events before enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2009;24:2102–2111. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnock DG, Thomas CP, Vujkovac B, Campbell RC, Charrow J, Laney DA, Jackson LL, Wilcox WR, Wanner C. Antiproteinuric therapy and Fabry nephropathy: factors associated with preserved kidney function during agalsidase-beta therapy. J Med Genet. 2015;52:860–866. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]