Abstract

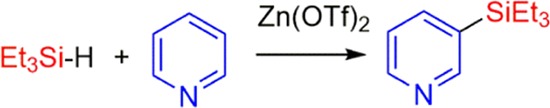

Zn(OTf)2 (OTf– = trifluoromethanesulfonate) catalyzes the silylation of pyridine, 3-picoline, and quinoline to afford the silylated products, where the silyl groups are meta to the nitrogen. The isolated yields of the products range from 41 to 26%. The 2- and 4-picolines yielded the silylmethylpyridines, where the CH3 groups were silylated instead of the ring. The pyridine silylation can occur via two separate pathways, involving either a 1,4- or a 1,2-hydrosilylation of pyridine as the first step. A byproduct of the pyridine silylation is a head-to-tail dimerization of N-silyl-1,4-dihydropyridine to form a diazaditwistane molecule.

Introduction

Recently, there has been tremendous interest in transforming C–H bonds into C–Si bonds,1 since the resulting silylated compounds provide a versatile set of molecules that can be used in various cross-coupling reactions.2 An interesting subset of this transformation is the silylation of N-heteroarenes, such as pyridine,3 picolines,4 quinolines,5 and indoles,6 where a C–H bond has been replaced with a C–Si bond.7 These transformations have involved transition metals4,6a and the rather unusual KOtBu6g,6i as catalysts. In addition, main group electrophilic Lewis acids, such as B(C6F5)3, can activate the silane to afford a silylated N-heteroarene.3a,5a Recently, Tsuchimoto and co-workers have reported the use of zinc salts as effective Lewis acid silylation catalysts for indoles.6j Herein, we report a series of easy-to-perform dehydrogenative silylation reactions that utilize commercially available zinc triflate as the catalyst. The silylation substrates are pyridine, picolines, and quinoline.

Results and Discussion

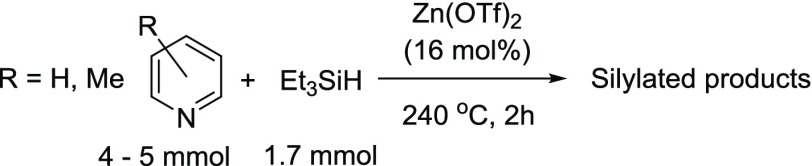

Reaction of Et3SiH with Pyridine and 3-Picoline

The reaction of pyridine with Et3SiH in the presence of 16 mol % Zn(OTf)2 (Table 1, entry 1) gave two products, 3-(triethylsilylpyridine) (1) and the disubstituted, 3,5-bis(triethylsilyl)pyridine, (2) in a 9:1 ratio of 1:2. In this reaction, Et3SiH is the limiting reactant with the pyridine in a 3-fold excess. The ratio of the two products can be changed to a 1.5:1 ratio, still in favor of 1 over 2 by making pyridine the limiting reactant (0.4 equiv relative to Et3SiH) and using 3,5-lutidine as the solvent. However, we were unsuccessful in fully converting 1 into 2 or having 2 be the main product of the reaction. The reaction of 3-picoline with Et3SiH (Table 1, entry 2) gave 3-methyl-5-(triethylsilyl)pyridine (3), where the Et3Si group is on the pyridine ring.

Table 1. Product Yields of Silylation Reactions with Zn(OTf)2.

Reaction of 2- and 4-Picolines with Et3SiH

The reaction of 4-picoline with Et3SiH gave 4-(triethylsilylmethyl)pyridine (4) (Table 1, entry 3) as the main product, while the reaction of 2-picoline with Et3SiH yielded 2-(triethylsilylmethyl)pyridine (5) (Table 1, entry 4). In both instances, the silylation occurred on the methyl group, instead of on the pyridine ring. These results are similar to what Fukumoto and co-workers have reported in their silylation of 2- and 4-picolines with Ir4(CO)12.4 The silylation of 4-ethylpyridine occurs at the benzylic position as well, to afford 4-(1-triethylsilylethyl)pyridine (14%, NMR-based yield).8

Attempts To Increase the Yield of 1

A 1H NMR spectrum (C6D6 or CDCl3 solvent) of the reaction headspace gas showed the presence of free H2.9 We did not attempt to quantify the amount of H2 produced in the reaction. We considered the possibility that the generated H2 was inhibiting the reaction and thus resulting in a diminished yield. The addition of hydrogen acceptors (cyclohexene and norbornene) did not substantially increase the yield of the products, which is in contrast to the work of Fukumoto and co-workers, where the addition of norbornene had a substantial impact on their reaction yields.4 We did not detect any hydrogenated products (cyclohexane or norbornane) in the reaction mixtures as well. While Beller and co-workers do note that Zn(OTf)2 can function as a catalyst in the hydrogenation of imines using H2, they do note that Zn(OTf)2 does not hydrogenate olefins.10

Also, the use of a more soluble form of Zn, Zn(NTf2)2, did not increase the yield of the reaction.

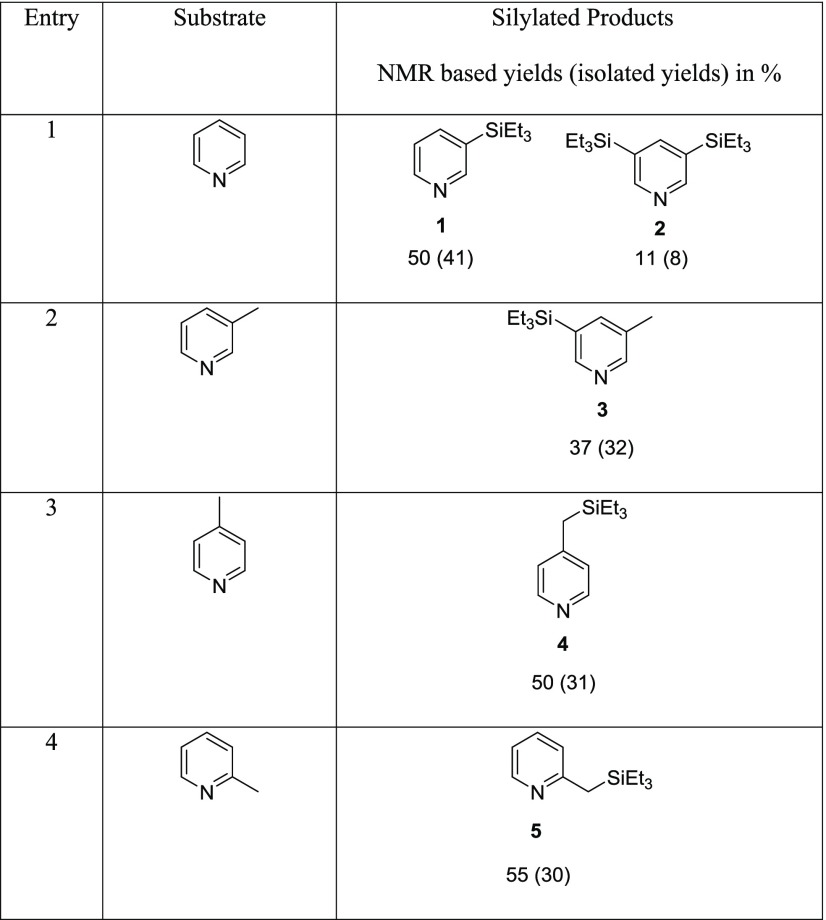

These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Use of Hydrogen Acceptors or a Different Zinc Salt in the Pyridine Silylation Reaction.

| zinc salt | additive | NMR-based % yield of 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Zn(OTf)2 | none | 50% |

| Zn(OTf)2 | norbornene | 55% |

| Zn(OTf)2 | cyclohexene | 51% |

| Zn(NTf2)2 | none | 33% |

We also tried cooling the reaction after 2 h, venting and purging with N2 and then reheating for an additional 2 h, to determine if physically removing the free H2 would increase the yield of the reaction. There was no noticeable effect on the yield of the reaction.

The use of another silane, Me2PhSiH, did not increase the reaction yield. We obtained the same yield (50%, based on NMR spectroscopy) of 3-(dimethylphenylsilyl)pyridine when using the same reaction conditions with pyridine, Zn(OTf)2, and Me2PhSiH.

Three to four turnovers are the typical range for the Zn(OTf)2 catalyst. The 1H NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture (Supporting Information, Figure S1) shows ∼20% of the free silane remaining in solution, yet running the reaction for longer periods of time (6 vs 2 h) did not increase the yield. One possibility that we did consider was that the catalyst was becoming inactive after a certain time period. However, recycling the Zn(OTf)2 from a previous reaction showed that the recycled Zn(OTf)2 was about 80% as effective as the fresh or unrecycled Zn(OTf)2. Therefore, we are at a loss as to why the combined amounts of 1 and 2 only reflect a 61% (NMR-based yield) incorporation of Si from Et3SiH. Given the high reaction temperatures, we were concerned that trace impurities in the Zn(OTf)2 were responsible for the actual catalysis. We did the same reaction (pyridine, Zn(OTf)2, Et3SiH, 240 °C, 2 h) using three different manufacturers of Zn(OTf)2 (TCI America, Acros, and Alfa Aesar), and the yields were within 2% of each other. While these reactions do not definitively rule out trace impurities as being the actual catalysts, it does bolster the argument that Zn(OTf)2 is the actual catalyst. A control reaction of just pyridine and Et3SiH at 240 °C for 2 h did not yield any product. Despite the high reaction temperature, a 1H NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture is fairly clean, with not a great deal of identifiable side products (Supporting Information Figure S1).

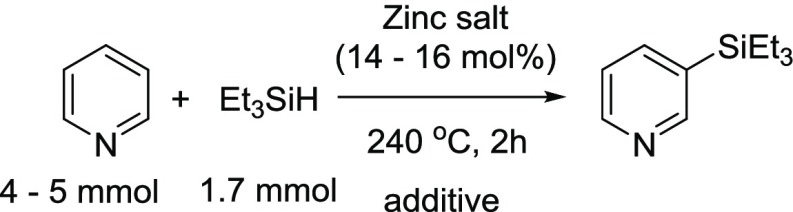

Proposed Mechanism for Pyridine Silylation To Form 1 and 2

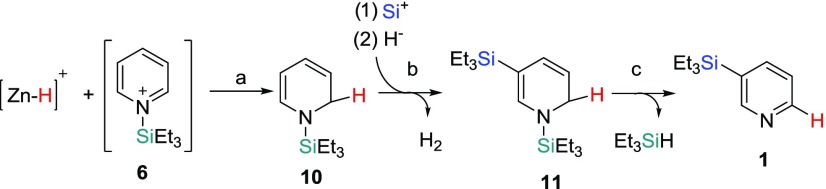

We believe that the mechanism of the pyridine silylation follows the same mechanism proposed by Oestreich and co-workers in their silylation reaction of substituted pyridines with a ruthenium complex (Scheme 1).3b The Zn2+ center interacts with a silane to form a pyridinium silyl cation (6)11 and a zinc hydride species (step a). We have been unable to detect either species by NMR spectroscopy, but both intermediates have been proposed as intermediates by Tsuchimoto co-workers in their silylation of indoles with Zn(OTf)2.6j We do observe a broad resonance (δ 5.30) in the 1H NMR spectrum when Zn(OTf)2, pyridine-d5, and Et3SiH are mixed together at room temperature (rt). This broad resonance has also been observed by Tsuchimoto and co-workers in their work with Zn(OTf)2 and silanes.12 However, we have been unable to isolate and fully characterize the compound that gives rise to this broad feature. Tsuchimoto and co-workers propose a Zn2+ and Et3SiH interaction to account for this observation. The Si+ species in the proposed mechanism could be in the form of 6 or as a [Zn–H–SiEt3]2+ species, while the H– could be in the form of a [(py)nZn–H]+ (py = pyridine) cation (monomeric or dimeric) in our proposed mechanism.13 Delocalization of the positive charge to the C4 position in 6 followed by a H– addition would lead to N-silyl-1,4-dihydropyridine (7) (step b).11,14 An electrophilic attack by a Si+ species to 7, to form a 1,3-bis(triethylsilyl)-3,4-dihydropyridinium cation, followed by loss of H2 would form the 1,3-bis(silyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine (8) intermediate (steps c and d).3b8 can then undergo a retrohydrosilylation14 to form 1 (step e) or undergo another electrophilic Si+ attack and loss of H2 to form 1,3,5-tris(silyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine (9) (step f). A retrohydrosilylation of 9 would then lead to the formation of 2 (step g).

Scheme 1. Proposed Mechanism for Pyridine Silylation.

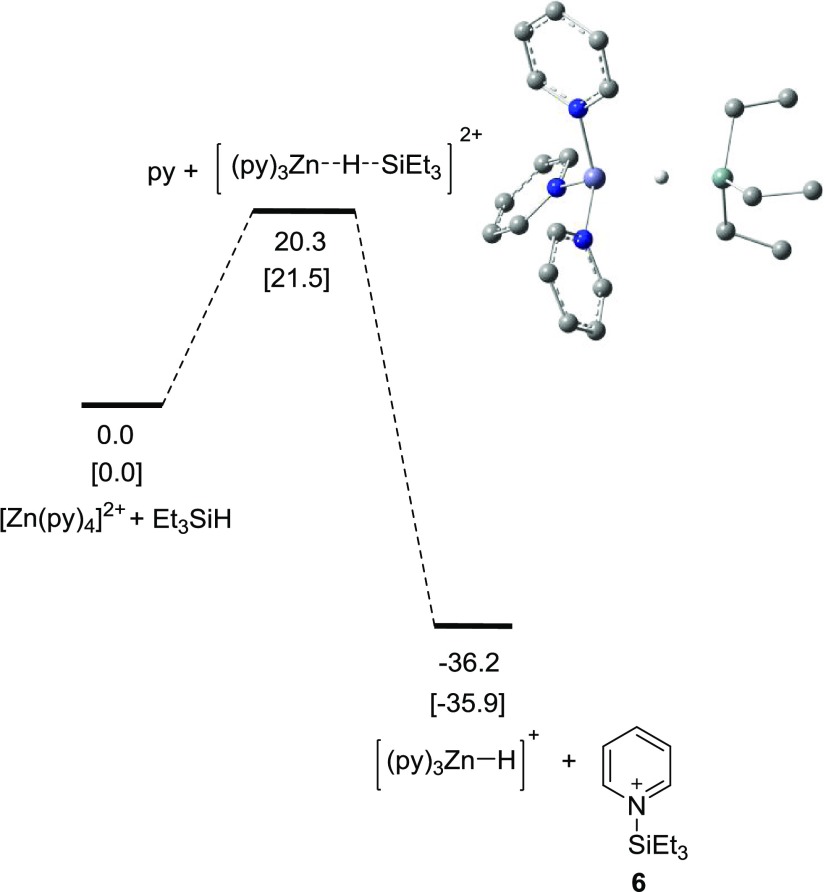

We performed some computational studies to determine the feasibility of the Zn2+ center forming a Zn–H species since we had very little data on the proposed step (a), Scheme 1. It is reasonable to assume that the Zn2+ would be surrounded by four pyridine molecules, given that pyridine is both the substrate and solvent and that the triflate anion would be just a counterion and not coordinated to the Zn2+ center. The loss of pyridine and coordination/interaction with a Et3SiH molecule was calculated to be +20.3 kcal/mol (Figure 1). The overall formation of 6 and [(py)3ZnH]+ was predicted to be exergonic by 36.2 kcal/mol from [Zn(py)4]2+ and Et3SiH. These results suggest that the proposed step (a) in Scheme 1 is thermodynamically possible.

Figure 1.

Energy profile for the formation of 6 calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. Relative free energies in the gas phase and enthalpies in the gas phase (in brackets) in kcal/mol are shown.

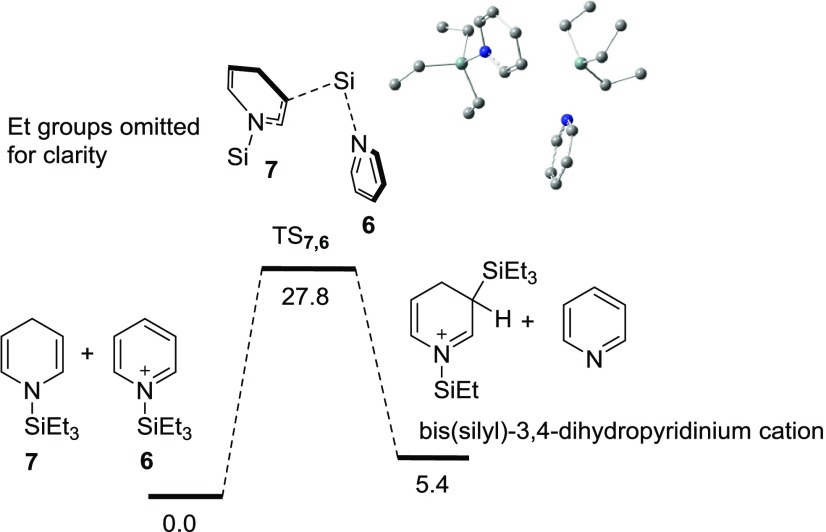

We were also interested in trying to determine if 6 was electrophilic enough to function as a Si+ source in step (c), Scheme 1, to form the proposed 1,3-bis(silyl)-3,4-dihydropyridinium cation intermediate, the precursor to 8. By considering the high-pressure conditions (240 °C, 11 atm) used in the experiment, the entropy contribution should be small enough so that enthalpy might be a better representation of the energies in this reaction. The relative energies are shown in Figure 2, with an enthalpy difference of 27.8 kcal/mol between 6, 7, and a possible transition state, TS7,6. The ΔH between the proposed 1,3-bis(silyl)-3,4-dihydropyridinium cation, pyridine and 6, 7 was determined to be endothermic by 5.4 kcal/mol. While the 27.8 kcal/mol represents a substantial energy barrier, it is readily accessible given the high reaction temperature of 240 °C. This does suggest that 6 can function as the Si+ source in the formation of 8 (Scheme 1, steps c and d).

Figure 2.

Energy profile for the reaction between 6 and 7 at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level. Relative enthalpies in the gas phase in kcal/mol are shown.

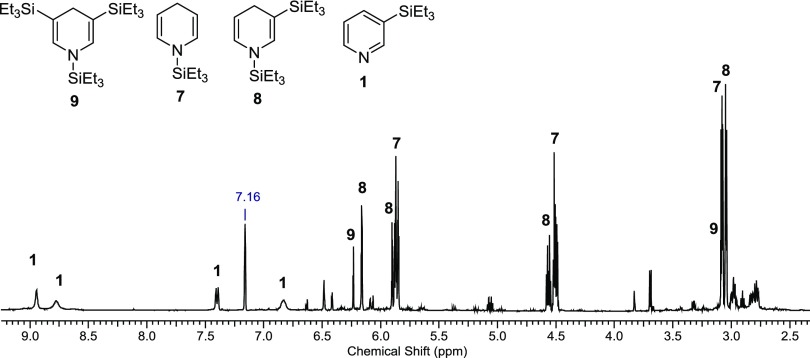

Running the reaction (Zn(OTf)2, pyridine, Et3SiH) at a lower temperature, 180 °C, 2 h, allowed us to observe several of the proposed intermediates in the reaction (Figure 3). We have good spectral evidence for intermediates 7 (Figure 3) and 8 (Supporting Information, Figures S13–S16) and tentative evidence for 9 (Supporting Information, Figure S17).

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture of py, Et3SiH, Zn(OTf)2 at 180 °C, 2 h, in C6D6.

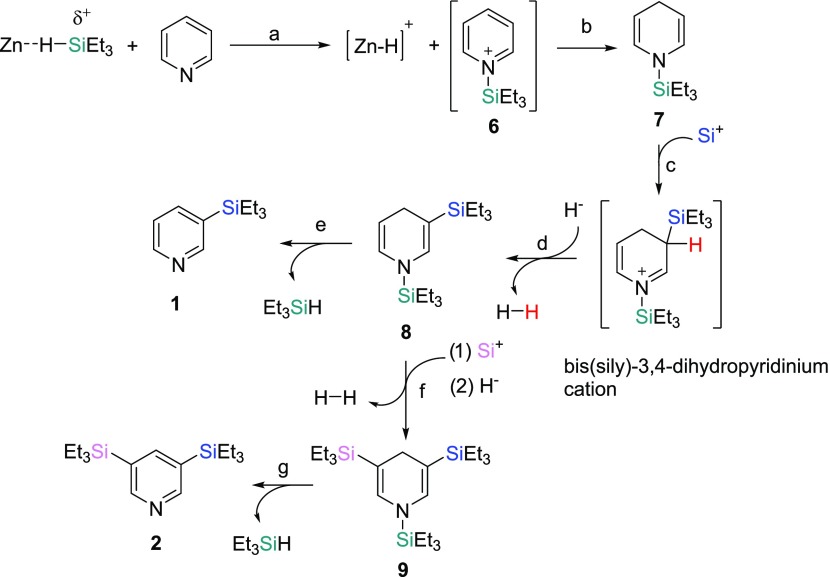

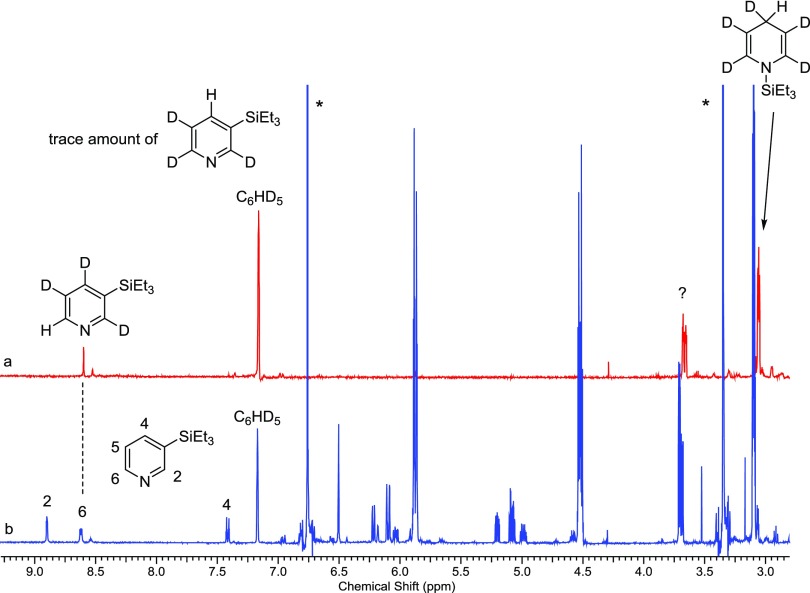

Reaction of Zn(OTf)2 and Et3SiH with Pyridine-d5

The reaction of pyridine-d5, Et3SiH, and Zn(OTf)2 at 180 °C, 10 min, afforded the expected deuterated 7 with a H at the C4 position, consistent with the proposed mechanism (Figure 4a). The gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis of the reaction mixture showed the silylated pyridine product, 1, with two masses consistent with 1-d4 (m/z 197) and 1-d3 (m/z 196). However, the 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture (Figure 4a) had a hydrogen resonance (δ 8.59) at the C6 position of 1 and not at the expected C4 position (δ 7.41) (Figure 4b shows the NMR spectrum of the pyridine-h5 reaction). The expected resonance for a hydrogen at C4 in 1-d3 was observed only in a trace amount in the 1H NMR spectrum. At longer reaction times (2 h, 180 °C), we do observe the hydrogen at C4 in 1-d3, but we were puzzled by the lack of a signal at short reaction times. In addition, there was a hydrogen resonance at δ 3.7 that we initially could not identify, indicated by a question mark in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra of deuterated and nondeuterated pyridine reactions. (a) 1H NMR spectrum of pyridine-d5 with Et3SiH and Zn(OTf)2 at 180 °C, 10 min. (b) 1H NMR spectrum of pyridine, Et3SiH, Zn(OTf)2, 180 °C, 10 min. Hydrogens of 1 are assigned in the spectrum. * = 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, internal standard.

To account for these observations, we took a closer look at the unassigned resonances in the mid-field region of the NMR spectrum (Figure 4b). By varying the reaction times at 180 °C and performing a series of microdistillations on the reaction mixtures, we have been able to identify and assign all of the resonances for two new intermediates, 1-(triethylsilyl)-1,2-dihydropyridine (10) (Supporting Information, Figures S18–S21) and 1,5-bis(triethylsilyl)-1,2-dihydropyridine (11) (Supporting Information, Figures S22–S25) (Scheme 2). Cook and Lyons have reported the trimethylsilyl analogs of 10 and 11, and our NMR spectral data closely matches their reported data.1510 is the result of a 1,2-addition of Et3SiH instead of a 1,4-addition (Scheme 2, step a).3a The addition of a Si+ group followed by loss of H2 would result in the formation of 11 (Scheme 2, step b). Loss of Et3SiH via a 1,2-retrohydrosilylation would result in a hydrogen at the C6 position of 1, which was initially the 2-position in 10. This would be consistent with the observed placement of the hydrogen in the pyridine-d5 reaction at the C6 position of 1-d3 (Figure 4a).

Scheme 2. Alternative Pathway for Pyridine Silylation, via an Initial 1,2-Addition Step.

Therefore, the silylation of pyridine to form 1 can occur via two different pathways, either a 1,2- or a 1,4-hydrosilylation addition as the initial steps.

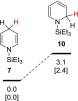

We were also interested in computationally determining the relative stability of 7 and 10 to try to gain some more insight into the two possible pathways, the 1,4-hydrosilylation (Scheme 1, steps (a and b)) vs the 1,2-hydrosilylation (Scheme 2, step (a)). Compound 7 was calculated to be slightly more stable than 10 by 3.1 kcal/mol (Figure 5). Therefore, in the initial hydrosilylation additions to form the dihydropyridine intermediates, there is not a large thermodynamic difference between one pathway over the other.

Figure 5.

Relative energy differences between 7 and 10 calculated at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level. Relative free energies in the gas phase and enthalpies in the gas phase [in brackets] in kcal/mol are shown.

Identification of an Unknown Organic Side Product

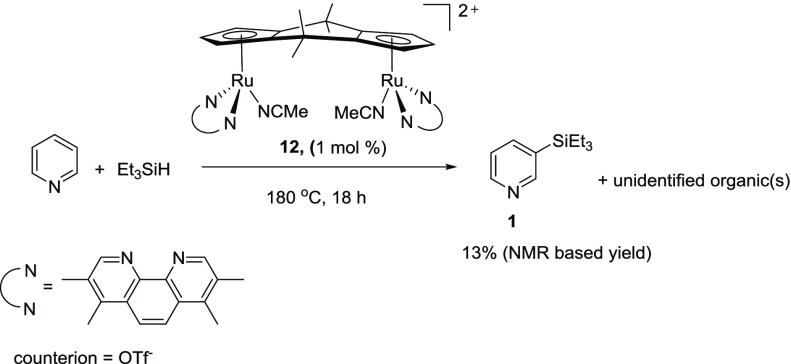

During the analysis of the organic products of the pyridine, Et3SiH, Zn(OTf)2 at 180 °C reaction, we also observed numerous small peaks in the 1–3 ppm region of the 1H NMR spectrum. We had previously observed these peaks (Supporting Information, Figure S28) in the reaction of [cis-{(η5-C5H3)2(CMe2)2}Ru2κ2-(Me4Phen)2(CH3CN)2][OTf]2 (12) (Me4Phen = 3,4,7,8-tetramethylphenanthroline) with pyridine and Et3SiH at 180 °C (eq 1). We believe that the reaction of pyridine with Et3SiH to form 1 using 12 as a catalyst follows the same reaction mechanism as proposed in Scheme 1, since we also observe intermediates 7 and 8 in the crude reaction mixture when 12 is used as the catalyst

|

1 |

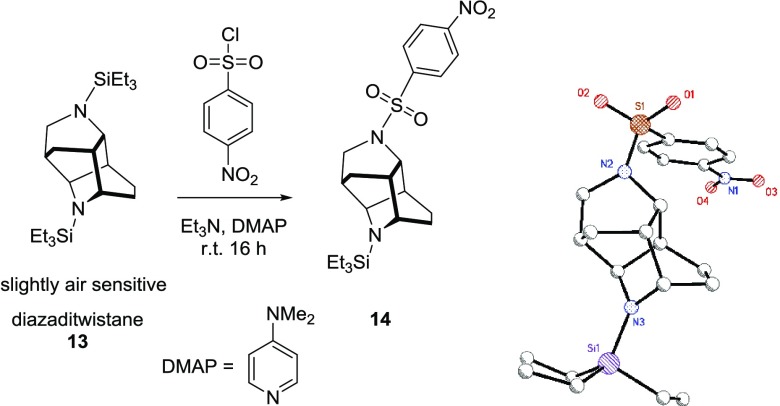

The GC/MS spectrum of the unidentified organic had a very small parent ion peak of 392 u, but the main peak had a mass of 196 u. This suggested a partially hydrogenated pyridine that had dimerized and contained two Et3Si groups and that the dimer was easily fragmented in the mass spectrometer. We had a difficult time determining the connectivity of the unknown molecule using various NMR spectroscopic techniques. The compound was also an oil and not amenable to crystallization at room temperature. We were inspired by the work of Chang and co-workers, where they sulfonated various silyl groups on partially hydrogenated N-silylpyridines to produce solids that could then be crystallized.3a The reaction of 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride with the unidentified organic provided a more stable compound that could then be crystallized (eq 2). Through a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study, we were able to establish the connectivity of the mystery molecule

|

2 |

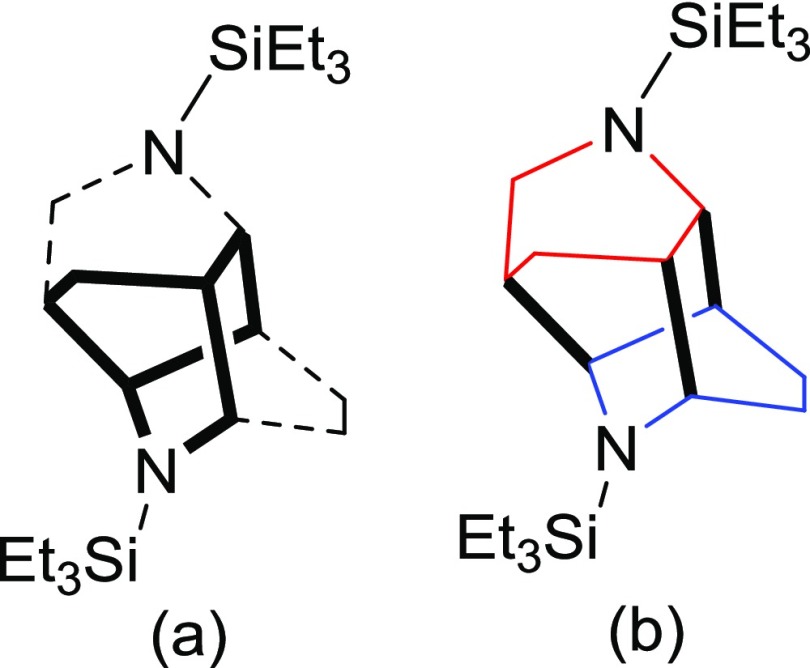

While the quality of the X-ray structure (Supporting Information, Table S1) does not allow for accurate bond lengths, we were able to determine the salient features of the molecule. The core of the molecule has a ditwistane configuration,16 and when the nitrogens are taken into consideration, it would be considered a diazaditwistane molecule (13).17 The sulfonation reaction only replaced one of the Et3Si groups to provide the monosulfonated version of a diazaditwistane derivative (14).

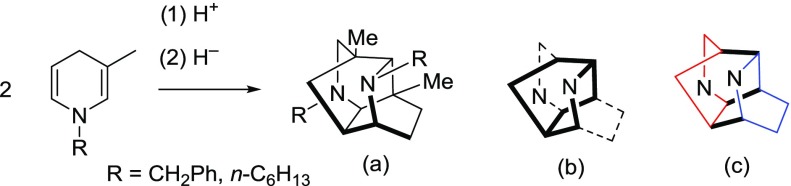

The structure of 13 is shown, where the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane core of a ditwistane molecule is in bold and the two diagonal ethano linkers are shown as dashed bonds (Chart 1a). The two individual dihydropyridine rings are shown in different colors, and the three newly formed bonds from the dimerization are shown in bold (Chart 1b).

Chart 1. Diazaditwistane Core (a) and 1,4-Dihydropyridines Dimerized (b).

With the structure in hand, a literature search gave us a remarkably similar molecule reported by Marazano and co-workers, where they report the dimerization of 1-(phenylmethyl)-3-methyl-1,4-dihydropyridine under acidic conditions (structure (a), eq 3).18 The bicyclo[2.2.2]octane core is highlighted in bold in structure (b), with the two diagonal ethano bridges as dashed lines. Structure (c) highlights the two different 1,4-dihydropyridine rings that have dimerized, while the bold lines show the new bonds that are formed in. The R and Me groups have been omitted for clarity in structures (b) and (c) (eq 3)

|

3 |

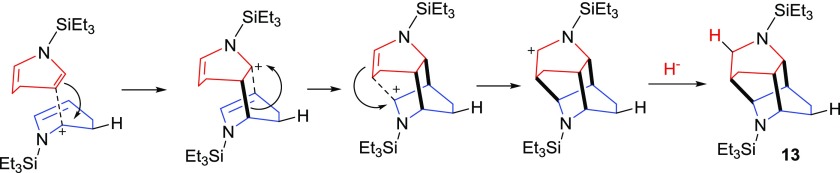

They propose an initial protonation to form a dihydropyridinium cation, which then cyclizes with another 1,4-dihydropyridine. Given the prevalence of 7 in our reaction mixture (with either Zn(OTf)2 or 12 as a catalyst), we propose that 13 forms via the same reaction mechanism as proposed by Marazano and co-workers. We believe that it is the initial protonation (bottom 1,4-dihydropyridine, Scheme 3) that sets off the “cascade” of reactions for the cyclization, where the positive charge is always ortho to a nitrogen. We are not sure whether the reactions are stepwise or concerted but show the reactions in a stepwise fashion for clarity purposes.

Scheme 3. Proposed Mechanism for the Formation of 13.

Ammon and Jensen have also reported the dimerization of 1-methyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide to form a similar structure under acidic conditions but they do not propose a mechanism for the product formation.19

The H+ source could be a dihydrogen complex20 when 12 is used as the catalyst or the heterolytic cleavage of a H2 molecule by the Zn2+ cation when Zn(OTf)2 is used as the catalyst.21 NMR spectral analysis of the crude reaction mixture (py, Et3SiH, 12 (1 mol %), 180 °C, 16 h) shows that ∼14% of the silicon from Et3SiH went into making 13. Although we only isolated 14 in 2% from the reaction (pyridine, Et3SiH, 12 (1 mol %), 130 °C, 16 h) and is therefore a minor side product, we thought it was still insightful in providing further evidence for the role and presence of 7 in the silylation of pyridine.

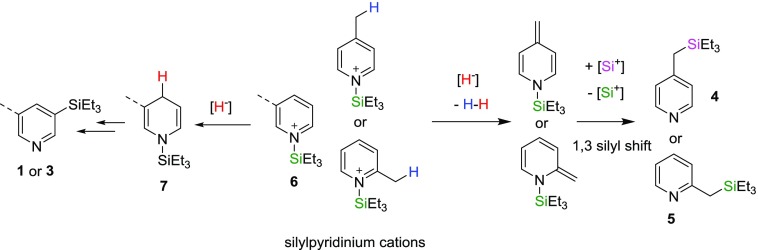

Silylation of the Pyridine Ring vs the CH3 Group in Picolines

A closer look at the possible mechanism for the silylation reaction helps explain the difference in the silicon placement, ring vs CH3 group. The common starting point is the reaction of the Si+ species with either pyridine or picoline to form the 1-(triethylsilyl)pyridinium 6 or 1-(triethylsilyl)picolinium cation. The reactivity differs as to whether a hydride adds to the 4-position (the left side of Scheme 4) or abstracts a H+ from one of the benzylic hydrogens (the right side of Scheme 4). The mechanism on the right mirrors the same proposed mechanism by Fukomoto and co-workers.4 When the CH3 group is either at the 2- or 4-position, the CH3 can undergo deprotonation by a hydride at the CH3 position to form the corresponding methylidene compounds and H2 (the right side of Scheme 4). The addition of Si+ to the methylidene C, following by the loss of Si+ (4-picoline substrate) or a 1,3-silylshift (2-picoline substrate), would then result in the silylmethylpyridine products, 4 and 5. However, we were unable to observe any of the proposed methylidene intermediates when the reaction was carried out at 180 °C, and therefore the proposed methylidene intermediates are still slightly speculative.

Scheme 4. Different Pathway for 4 and 5 Formations.

When pyridine or 3-picoline are the substrates, the addition of H– to the 4-position of the silylpyridinium cation would afford intermediate 7 instead, which would then lead to the eventual formation of 1 or 3 (the left side of Scheme 4).

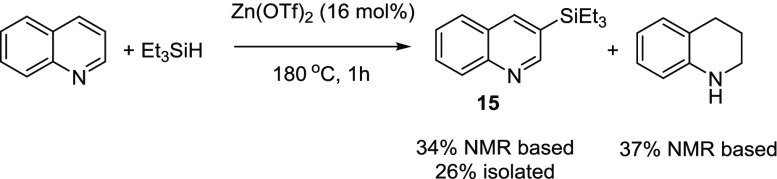

Silylation of Quinoline

Quinoline is one of the more challenging substrates to silylate given its propensity to be hydrogenated to tetra and dihydroquinolines.5a Murai and co-workers have previously reported the silylation of quinoline at the 8-position using an iridium complex,5b while Ito and co-workers have reported the silylation of quinoline at the 2-position using a boron-based reagent under basic conditions.22 The reaction of quinoline, Et3SiH with Zn(OTf)2 at 180 °C, 1 h afforded 3-triethylsilylquinoline (15) in a 26% yield (eq 4). The 1H NMR spectrum also showed the presence of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (37% NMR-based yield)

|

4 |

We had initially performed the reaction in a closed microwave tube, where the NMR-based yield of 15 was 27%. We thought that performing the reaction in an open system, under 1 atm of nitrogen, would increase the yield by allowing any free H2 to escape, thereby decreasing the amount of tetrahydroquinoline produced. While performing the reaction in an open system did increase the yield by ∼7%, it also increased the amount of tetrahydroquinoline by about the same amount! Therefore, the ratio of 15: tetrahydroquinoline was about the same, 1:1.2, regardless of whether the system was open or closed. We do not understand the reason for the increase in yield when an open system is used. We do not observe any remaining Et3SiH in the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture after 1 h. Therefore, longer reaction times (2 vs 1 h) did not affect the yield of the reaction. We believe the reason for the formation of the tetrahydroquinoline is that a 1,2-hydrosilylation of the quinoline would not afford 15, unlike the case of pyridine and Et3SiH (Scheme 2). The 1,4-hydrosilylation23 pathway would lead to the formation of 15. These two competing pathways are shown in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Alternative Pathways for Quinoline Silylation.

Nikonov and co-workers have also observed both the 1,2- and 1,4-hydrosilylations of quinoline with their [CpRu(iPr3P)(NCMe)2]+ catalyst using Me2PhSiH as the silane.24 We have tentative 1H NMR spectral evidence for the formation of N-triethylsilyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline, when the NMR sample of the crude reaction mixture is made up under inert conditions. The observed resonances closely match those of N-trimethylsilyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline.25 The N-silyltetrahydroquinoline product is rapidly hydrolyzed upon exposure to air to form 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline. Chang and co-workers have also seen similar reactivity in the conversion of their N-silylated species to the N–H products upon silica gel chromatography.5a

Conclusions

In summary, we have reported the dehydrogenative silylation of pyridine, picolines, and quinoline using Zn(OTf)2, a readily available reagent. We believe that the observed intermediates for the pyridine silylation are consistent with an electrophilic aromatic substitution (SEAr)-type mechanism, with the Zn2+ center activating the silane. While the yields are moderate (42%) to very modest (26%), we believe that these reactions are still noteworthy, due to the ease and simplicity in transforming pyridine, picolines, and quinoline to various silylated products with Zn(OTf)2.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

Reactions that required inert conditions were performed using modified Schlenk techniques or in an MBraun Unilab glovebox under a nitrogen atmosphere. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity Inova 400 MHz spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts are given relative to the residual proton or 13C solvent resonances. NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature (20–25 °C) unless otherwise noted. GC/MS data were collected on an Agilent 6890 Series GC connected to a HP 5973 mass detector. Elemental analyses were performed using a Thermo Electron Flash EA 1112 Series analyzer. Microwave heating was conducted using a CEM Discover SP instrument in either 10 or 35 mL snap cap pressure tubes or in an open vessel mode. The temperature of the reactions in the microwave was monitored using the floor-mounted IR sensor in the instrument (external surface measurement).

Safety Note

The pressures when performing the microwave reactions at 240 °C reached 11 atm, which are within the stated tolerances of the tubes provided by CEM. When heating the reactions at 170–180 °C in an oil bath, Ace pressure tubes were used. We believe that the pressure at that temperature range is ∼5 atm. All oil bath reactions were conducted behind a blast shield with the appropriate personal protective equipment.

Solvents and Reagents

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals were used as received. Common solvents and reagents were purchased from Acros, Fisher Scientific, VWR, or TCI America. Deuterated solvents were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. 4-Picoline, 2-picoline, 3-picoline, 3,5-lutidine, C6H6, Et3SiH, CDCl3 and C6D6, and CD3CN were degassed and dried over 3 Å sieves. Pyridine and quinoline were dried over CaH2 (room temperature, overnight), vacuum-distilled, and stored over 3 Å sieves. All glassware were heated to 120 °C before being brought into the glovebox. 3,4,7,8-Tetramethylphenanthroline (Me4Phen) was purchased from Acros and used as received. [cis-{(η5-C5H3)2(CMe2)2}Ru2(μ-η6,η6-C10H8)][OTf]2 was prepared as previously described.26

Computational

All geometries of reactants, transition states (TSs), intermediates, and products were fully optimized in the gas phase by Gaussian 09, D01 program with B3LYP functional.27 The 6-31G(d,p) basis set was used for all atoms in the reaction shown in Figure 1.28 The 6-311+G(d,p) basis set was used for calculations in Figures 2 and 3.28b,29 Frequency calculations at the same level of theory were carried out to verify all stationary points as minima (zero imaginary frequency) and transition states (one imaginary frequency) and also to provide free energies. The reported energies are the relative Gibbs free energies and enthalpies with thermal corrections in kcal/mol.

Preparation of 3-(Triethylsilyl)pyridine (1) and Bis-3,5-(triethylsilyl)pyridine (2)

Zn(OTf)2 (99.90 mg, 0.2748 mmol, 16 mol %) was added to an oven-dried 10 mL CEM microwave pressure tube in an inert atmospheric glovebox. Pyridine (405.1 mg, 5.128 mmol) and Et3SiH (199.8 mg, 1.722 mmol) were added to the tube. The tube was placed into a CEM Discover microwave and heated to 240 °C for 2 h. The resulting dark brown solution was transferred to a 50 mL round-bottom flask using 3 × 1 mL CH2Cl2, and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. Hexane (50 mL) was added to the semisolid oil, and the hexane solution was passed through a SiO2-padded frit (15 mL size). Et2O (50 mL) was then used to elute the products off the SiO2-padded frit. The solution was collected, and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. A 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture showed a mixture of 1 and 2 in a 9:1 ratio. 1 was purified by a vacuum microdistillation (40 mtorr, 80 °C = flask temperature) to afford a clear liquid (138.0 mg, ∼99% purity, 41% yield based on Et3SiH). A preparative TLC (20 × 20 cm, 2000 μm, SiO2 plate, 10 vol % EtOAc: 90 vol % hexane) was performed on the bottom residue from the distillation. The top band (Rf = 0.45) was collected and extracted with EtOAc (70 mL) to afford pure 2 as a liquid (21.6 mg, 0.0704 mmol, 8%). A previous reaction with similar amounts of reactants at the same temperature and reaction time showed the crude reaction yields of 1 to be 168.1 mg, 0.8709 mmol, 50% and 2 to be 29.24 mg, 0.0953 mmol, 11%, determined using 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as an internal standard in the NMR spectrum. The 1H NMR spectral data in CDCl3 matched the previously reported data.30 The NMR spectrum of 1 in C6D6 is reported since the spectrum shows all four aromatic peaks with no overlapping solvent peaks. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 8.90–8.87 (m, 1H), 8.60 (dd, 3JHH = 5.1 Hz, 4JHH = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dt, 3JHH = 7.4 Hz 4JHH = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (ddd, 3JHH = 7.4, 4.9 Hz, 4JHH = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 0.86 (t, 3JHH = 7.4 Hz, 9H), 0.62 (q, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 6H). NMR spectral data for 2, 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 8.97 (d, 4JHH = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.97 (t, 4JHH = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 0.91 (t, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 18H), 0.70 (q, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 12H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 156.1 (CH), 148.0 (CH), 131.3 (quat C), 7.8 (CH3), 3.8 (CH2). GC/MS: m/z 307 (11), 278 (100), 250 (80), 222 (54). Anal. calcd for C17H33NSi2: C, 66.37; H, 10.81 found: C, 65.89; H, 10.92.

Reaction To Favor the Formation of 2

Zn(OTf)2 (116.9 mg, 0.3216 mmol), pyridine (106.2 mg, 1.344 mmol), 3,5-lutidine (296.2 mg), and Et3SiH (360.0 mg, 3.103 mmol) were added to a microwave glass tube. The contents were heated in a CEM Discover microwave at 250 °C for 2 h. 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene (39.5 mg, 0.2862 mmol) was added to the orange solution, and the solution was mixed thoroughly. A 1H NMR spectrum of an aliquot was recorded in C6D6. The spectrum showed 0.4436 mmol of 1 and 0.2976 mmol of 2 based on the added 1,4-dimethoxybenzene.

Preparation of 3-Methyl-5-(triethylsilyl)pyridine (3)

Zn(OTf)2 (103.6 mg, 0.2850 mmol, 16 mol %) was added to an oven-dried 10 mL CEM microwave pressure tube in an inert atmospheric glovebox. 3-Picoline (401.8 mg, 4.320 mmol) and Et3SiH (202.9 mg, 1.749 mmol) were added to the tube. The tube was placed into a CEM Discover microwave and heated to 240 °C for 2 h. The yellow solution was transferred to a 50 mL round-bottom flask using 3 × 1 mL CH2Cl2, and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. Hexane (50 mL) was added to the semisolid oil, and the hexane solution was passed through a SiO2-padded frit (15 mL size). Et2O (50 mL) was then used to elute the products off the SiO2-padded frit. The solution was collected, and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. 3 was purified by a vacuum microdistillation (40 mtorr, 100 °C = flask temperature) to afford a clear liquid. A 1H NMR spectrum of the product showed some Et3SiOH present in the sample. The clear liquid was placed under a vacuum for 30 min to afford 120.3 mg. The 1H NMR spectrum showed the product to be ∼94 mol % pure (∼96 mass% purity, assuming the impurity is Et3SiOH, 32% yield). A previous reaction with similar amounts of reactants at the same temperature and reaction time showed the crude reaction yield of 3 to be 137.5 mg, 0.6645 mmol, 40%, determined using 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as an internal standard in the NMR spectrum. The 1H NMR spectral data in CDCl3 matched the previously reported data,4b with the exception of the resonance reported at δ 7.26, which we suspect is a typographical error and should be δ 7.55. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.46 (br s, 1H), 8.41 (d, 4JHH = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.54 (m, 1H), 2.33 (s, 3H), 0.97 (t, 3JHH = 7.4 Hz, 9H), 0.81 (q, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 6H).

Preparation of 4-(Triethylsilylmethyl)pyridine (4)

Zn(OTf)2 (101.5 mg, 0.2792 mmol, 16 mol %) was added to an oven-dried 10 mL CEM microwave pressure tube in an inert atmospheric glovebox. 4-Picoline (400.8 mg, 4.310 mmol) and Et3SiH (198.6 mg, 1.712 mmol) were added to the tube. The tube was placed into a CEM Discover microwave and heated to 240 °C for 2 h. The vibrant green mixture was transferred to a 50 mL round-bottom flask using 3 × 1 mL CH2Cl2, and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. The green color quickly faded to a pale yellow upon adding the CH2Cl2. Hexane (50 mL) was added to the semisolid oil, and the hexane solution was passed through a SiO2-padded frit (15 mL size). Et2O (50 mL) was then used to elute the products off the SiO2-padded frit. The solution was collected, and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. 4 was purified by a vacuum microdistillation (40 mtorr, 100 °C = flask temperature) to afford a clear liquid (128.2 mg). A 1H NMR spectrum of the liquid showed two impurities along with 4, with an approximate composition of ∼85 mol % 4. Assuming the mol %–mass %, the yield of 4 is ∼31%. A previous reaction with similar amounts of reactants at the same temperature and reaction time showed the crude reaction yield of 4 to be 163.3 mg, 0.7887 mmol, 46%, determined using 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as an internal standard in the NMR spectrum. The 1H NMR spectral data in CDCl3 matched the previously reported data.4a

Preparation of 2-(Triethylsilylmethyl)pyridine (5)

Zn(OTf)2 (98.8 mg, 0.2718 mmol, 16 mol %) was added to an oven-dried 10 mL CEM microwave pressure tube in an inert atmospheric glovebox. 2-Picoline (429.9 mg, 4.623 mmol) and Et3SiH (205.0 mg, 1.767 mmol) were added to the tube. The tube was placed into a CEM Discover microwave and heated to 240 °C for 2 h. The dark brown solution was transferred to a 50 mL round-bottom flask using 3 × 1 mL CH2Cl2, and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. Hexane (50 mL) was added to the dark oil, and the hexane solution was passed through a SiO2-padded frit (15 mL size). Et2O (50 mL) was then used to elute the products off the SiO2-padded frit. The solution was collected, and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. 4 was purified by a vacuum microdistillation (40 mtorr, 100 °C = flask temperature) to afford a clear liquid (114.3 mgs). The 1H NMR spectrum showed the product to be ∼97 mol % pure (∼97 mass% purity, assuming the impurity is 2-methyl-5-(triethylsilyl)pyridine), (30% yield). A previous reaction with similar amounts of reactants at the same temperature and reaction time showed the crude reaction yield of 4 to be 198.6 mg, 0.9592 mmol, 55%, determined using 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as an internal standard in the NMR spectrum. The 1H NMR spectral data in CDCl3 matched the previously reported data.4b

Observation of Intermediates 7, 8, and 9, for the Pyridine, Et3SiH, and Zn(OTf)2 Reactions at 180 °C, 2 h

Zn(OTf)2 (98.0 mg, 0.270 mmol, 16 mol %), pyridine (397.1 mg, 5..027 mmol), and Et3SiH (196.6 mg, 1.695 mmol) were placed in an oven-dried microwave pressure tube. The contents were heated in a CEM Discover microwave reactor at 180 °C for 2 h. At the end of the reaction, the reaction was light yellow. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the crude reaction mixture was brought into the glovebox. The organics were extracted with pentane (2 × 3 mL) and filtered to remove the Zn(OTf)2. The yellow solution was collected, and the pentane was removed under reduced pressure. The NMR spectrum showed the ratio of 7:8:9 to be 6.3:3.2:1. The spectral data for 7 matched the reported data by Oestreich and co-workers.11 The residual oil was then heated in a round-bottom flask at 60 °C for 30 min under reduced pressure (40 mtorr). Most of the more volatile 7 evaporated from the flask, while 8 coated the walls of the round-bottom flask and 9 stayed primarily on the bottom of the flask. 9 was extracted from the flask by carefully pipetting the C6D6 into the flask to just dissolve the contents on the bottom. A 1H NMR spectrum of concentrated 8 was then obtained by dissolving the contents off the wall of the flask.

NMR Spectral Data for 1,3-Bis(triethylsilyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine (8)

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 6.18 (br s, 1H), 5.90 (dq, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 4JHH = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (dt, 3JHH = 8.2, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.08–3.05 (m, 2H), 1.05 (t, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 9H), 0.90 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 9H), 0.64 (q, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 6H), 0.53 (q, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 136.4 (CH), 129.2 (CH), 102.9 (quat C), 100.6 (CH), 24.9 (CH2), 8.2 (CH3), 7.3 (CH3), 4.3 (CH2), 3.2 (CH2). GC/MS: m/z 308 (100) [M – 1], 280 (18), 194 (9).

NMR Spectral Data for 1,3,5-Tris(triethylsilyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine (9)

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 6.25 (t, 4JHH = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 3.10 (t, 4JHH = 1.2 Hz, 2H). The ethyl resonances could not be reliably identified. GC/MS: m/z 422 (100) [M – 1], 394 (7), 308 (19).

Reaction of Zn(OTf)2, Pyridine, and Et3SiH To Maximize Intermediates 10 and 11

The reaction amounts and conditions were the same for the 180 °C, 2 h reaction as described above, except that the reaction time was only 5 min instead of 2 h. The organic intermediates were extracted with pentane and filtered, and the more volatile 10 was collected by microdistillation (70 °C = flask temperature, 30 min, 40 mtorr), while the less volatile 11 remained in the bottom of the flask.

NMR Spectral Data for 1-(Triethylsilyl)-1,2-dihydropyridine (10)

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 6.21 (d, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz 1H), 6.05–6.00 (m, 1H), 5.22–5.17 (m, 1H), 5.01–4.95 (m, 1H), 3.68 (dd, 3JHH = 4.3 Hz, 4JHH = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 0.88 (t, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 9H), 0.48 (q, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 136.9 (CH), 126.2 (CH), 109.1 (CH), 102.2 (CH), 43.7 (CH2), 7.4 (CH3), 4.0 (CH2). GC/MS: m/z 194 (100) [M – 1], 166 (5), 115 (27), 87 (49).

NMR Spectral Data for 1,5-Bis(triethylsilyl)-1,2-dihydropyridine (11)

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 6.51 (br s, 1H), 6.12–6.08 (m, 1H), 5.10–5.05 (m, 1H), 3.70 (dd, 3JHH = 4.3 Hz,, 4JHH = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 1.09 (t, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 9H), 0.90 (t, 3JHH = 7.4 Hz, could not obtain a reliable integration due to overlapping peaks), 0.71 (q, 3JHH = 8.2 Hz, 6H), 0.53 (q, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, could not obtain a reliable integration due to overlapping peaks). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 144.0 (CH), 109.7 (CH), 103.3 (quat C), 43.6 (CH2), 8.2 (CH3), 7.4 (CH3), 4.3 (CH2), 4.2 (CH2). C4 resonance overlaps with the solvent peak. GC/MS: m/z 308 (100) [M – 1], 280 (9), 194 (7), 154 (36), 136 (44), 108 (30), 87 (24), 59 (15).

Preparation of [cis-{(η5-C5H3)2(CMe2)2}Ru2κ2-(Me4Phen)2(CH3CN)2][OTf]2 (12)

[cis-{(η5-C5H3)2(CMe2)2}Ru2(μ-η6,η6-C10H8)][OTf]2 (295.1 mg, 0.3521 mmol) was dissolved in CH3CN (8.9856 g), and the orange solution was evenly pipetted into eight 5 mm NMR tubes. The tubes were placed on the inside of the coils of a compact fluorescent bulb (105 W, 5000 K temperature rating, 6600 lumens) and photolyzed for 4 h. The tubes were cooled by streaming room-temperature compressed air across the tubes during the photolysis period. The light yellow solutions were combined into a single round-bottom flask, and the acetonitrile was removed in vacuo. The complex was then dissolved in CH3CN (2.0259 g) and transferred to a 10 mL microwave glass tube. Me4Phen (175.0 mg, 0.7415 mmol) was also added to the solution, and the solution was heated to 80 °C for 20 min using a CEM microwave reactor. The resulting solution was dark red. The solution was brought into the glovebox and added to Et2O (50 mL). The mixture was filtered to yield an orange-red solid. The solid was washed with more Et2O (2 × 5 mL), THF (3 × 5 mL), cold CH3CN (0.5 mL), and finally Et2O (1 × 3 mL). The solid was dried in vacuo to afford 339.0 mg, 0.268 mmol, 76%. The NMR spectra were recorded at 80 °C due to the hindered rotation of the two rutheniums about their piano stool axes. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN, 80 °C): δ 9.55 (s, 4H), 8.07 (s, 4H), 4.44 (d, 3JHH = 2.0 Hz, 4H), 3.96 (t, 3JHH = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (s, 12H), 2.52 (s, 12H), 1.96 (s, 6H), 1.57 (s, 6H). The bound CH3CNs are not observed due to rapid exchange with CD3CN. 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN, 80 °C) δ 157.9 (CH), 147.2 (quat C), 144.67 (quat C), 134.4 (quat C), 129.7 (quat C), 124.5 (CH), 98.5 (quat C) 74.3 (CH), 63.3 (CH), 38.9 (CH3), 35.5 (quat C), 30.1 (CH3), 17.9 (CH3), 15.3 (CH3). Anal. calcd for C54H56N6Ru2F6S2O6: C, 51.26; H, 4.46 found: C, 51.01; H, 4.32.

Preparation and Semipurification of 13

Compound 12 (24.6 mg, 0.0194 mmol, 1 mol %), pyridine (414.2 mg, 5.243 mmol), and Et3SiH (196.2 mg, 1.691 mmol) were added to a 5 mL Ace glass pressure tube. The contents were heated at 170 °C for 17 h in an oil bath. The dark red/purple solution was brought back into the glovebox, transferred to a round-bottom flask with CH2Cl2 (3 × 0. 5 mL), and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure with heating (40 °C, 40 min). Pentane (∼5 mL) was added to the dark purple semisolid, and the mixture was filtered using a Kim-wipe plugged pipet. The pentane was removed under reduced pressure, and the resulting red oil was washed with acetonitrile (4 × 0.5 mL). The desired product, 13, is not soluble in acetonitrile. The remaining oil was transferred to a sublimation flask, and the product was distilled onto a liquid-nitrogen-cooled cold finger (105 °C flask temperature, 20 min, 40 mtorr) to afford 54.4 mg of a clear oil that contained mostly 13.

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 3.02–2.94 (m, 2H), 2.86–2.76 (m, 3H), 1.99–1.92 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.86 (m, 1H), 1.81–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.48 (m, 2H), 1.34–1.25 (m, 1H) 1.08–1.03 (m, 18H), 0.66–0.58 (m, 12H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 51.8 (CH), 51.0 (CH), 50.6 (CH), 45.9 (CH2), 40.1 (CH), 37.8 (CH), 34.4 (CH), 24.6 (CH2), 26.3 (CH2), 23.0 (CH2), 8.21 (CH3), 8.1 (CH3), 5.4 (CH2), 4.8 (CH2). GC/MS: m/z 392 (4) [M], 196 (100).

Preparation of 14

In a glovebox, pyridine (640.1 mg, 8.103 mmol), Et3SiH (210.5 mg, 1.815 mmol), and 12 (34.1 mg, 0.02695 mmol, 1.5 mol %) were added to a valved ampule and placed in an oil bath at 130 °C for 19 h. The reaction was carried out at 130 °C instead of 180 °C with the intent to maximize the formation of 13. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure to yield a dark red/purple oil. The ampule was brought back into the glovebox, and the oil was washed with pentane (4 × 1 mL), and the pentane solution was filtered through a Kim-wipe plugged pipet. The pentane solution was collected, and the pentane was removed in vacuo to yield 102.9 mg of crude 13. Impure compound 13 was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (404.5 mg) and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (4.1 mg, 0.0336 mmol), Et3N (54.2 mg, 0.5366 mmol) added to the mixture. 4-Nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (85.3 mg, 0.3842 mmol) was then added as a solid to the mixture, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at rt for 16 h. The reaction solution was brought out of the N2-filled glovebox, and water (2 mL) and CH2Cl2 (1 mL) were added to the resulting red solution. The CH2Cl2 fraction was collected, washed with water (3 × 1 mL), dried with MgSO4, filtered, and the CH2Cl2 removed under reduced pressure, resulting in a brown solid (123.8 mg). The solid was placed on a microfrit and washed with cold acetonitrile (3 × 0.25 mL) to afford an off-white powder (10.6 mg, 0.0222 mmol, 2% based on starting silane). 14 will slowly decompose in the presence of water. Although the reaction workup was outside of the glovebox, all subsequent manipulations of pure 14 were conducted in a N2-filled glovebox (crystal growing setups and NMR sample preparation).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.36 (d, 3JHH = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.00 (d, 3JHH = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (d, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (dd, JHH = 10.2, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.04–2.95 (m, 2H), 2.91 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.29–2.22 (m, 1H), 2.10–2.04 (m, 1H), 1.78–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.62 (m, 1H) 1.61–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.44–1.29 (m, 3H), 0.92 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 9H), 0.52 (q, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 149.8 (quat C), 145.3 (quat C), 128.1 (CH), 124.3 (CH), 53.0 (CH), 49.59 (CH), 49.54 (CH), 47.2 (CH2), 36.8 (CH), 34.1 (CH), 32.5 (CH), 26.3 (CH2), 24.9 (CH2), 21.5 (CH2), 7.3 (CH3), 4.4 (CH2). Anal. calcd for C22H33N3O4SSi: C, 56.99; H, 7.17 found: C, 56.89; H, 6.96.

Preparation of 15

Zn(OTf)2 (222.1 mg, 0.6110 mmol, 16 mol %), quinoline (1.1459 mg, 8.882 mmol), and Et3SiH (448.2 mg, 3.864 mmol) were placed into an oven-dried 5 mL round-bottom flask in the glovebox. The round bottom was then placed in a CEM Discover microwave, and the reaction was heated to 180 °C for 1 h in the open vessel mode, under a N2 atmosphere. The resulting liquid quickly solidified upon cooling. The contents of the flask were placed in a beaker, and the product was extracted with hexanes (80 mL). The hexane solution was filtered through a SiO2-padded frit (30 mm of SiO2, 30 mL size frit). The hexane fraction was discarded, and the SiO2 was washed with CH2Cl2 (100 mL) to give a light yellow solution. The CH2Cl2 was removed under reduced pressure to afford a yellow oil (734.6 mg). The oil was microdistilled (40 mtorr). The first fraction (temperature of the flask = 55 °C, 15 min) contained mostly tetrahydroquinoline and quinoline. The second fraction was collected by heating the flask to 160 °C, 25 min, 40 mtorr, to afford 15 as a liquid (247.0 mg, ∼95 mol % pure, ∼26%). The 1H NMR spectrum of 15 in CDCl3 matched that of the previously reported spectral data.31

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction of 14

A crystal (0.126 × 0.097 × 0.062 mm3) was placed onto a thin glass optical fiber and mounted on a Rigaku XtaLab Synergy-S Dualflex diffractometer equipped with a HyPix-6000HE HPC area detector for data collection at 99.9(5) K. A preliminary set of cell constants and an orientation matrix were calculated from a small sampling of reflections.32 A short pre-experiment was run, from which an optimal data collection strategy was determined. The full data collection was carried out using a PhotonJet (Cu) X-ray source with frame times of 1.12 and 4.50 seconds and a detector distance of 31.2 mm. A series of frames were collected in 0.50° steps in ω at different 2θ, κ, and ϕ settings. After the intensity data were corrected for absorption, the final cell constants were calculated from the xyz centroids of 19583 strong reflections from the actual data collection after integration.32

The structure was solved using ShelXT33 and refined using ShelXL.34 The space group P63/m was determined based on systematic absences and intensity statistics. Most or all nonhydrogen atoms were assigned from the solution. Full-matrix least-squares/difference Fourier cycles were performed, which located any remaining nonhydrogen atoms. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. All hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. The final full-matrix least-squares refinement converged to R1 = 0.1365 (F2, I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 = 0.3702 (F2, all data).

All crystals were grown from a myriad of solvents and conditions compatible with the material crystallized with the same packing arrangement. This structure was solely for use as independent support of the formulation, consistent with that determined by spectroscopic techniques.

The structure is the one suggested. The asymmetric unit contains one-half of a molecule on a crystallographic mirror plane and cocrystallized solvent that was not modeled. The entire molecule is modeled as disordered over the mirror plane (0.50:0.50). The SiEt3 group is modeled as additionally disordered over two general positions (0.74:0.26). Due to the severity of the disorder in the SiEt3 group, the carbon atoms were refined isotropically. Highly disordered cocrystallized solvent found in channels along [001] was neither assigned atoms nor SQUEEZEd,35 because neither treatment made any significant difference to the overall structural quality.

A summary of the crystal data is given in the Supporting Information (Table S1).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Science Foundation (CHE-1565893) for supporting this work. X-ray data were obtained at the University of Rochester, funded by NSF MRI CHE-1725028. R.M.C. thanks the UNI graduate college for a professional development assignment. The authors also thank the CHAS-Dean’s office for support for R.V. and Victoria Williams and Eric Gleiter for assisting in various pyridine silylation reactions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03317.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Cheng C.; Hartwig J. F. Catalytic Silylation of Unactivated C–H Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8946–8975. 10.1021/cr5006414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yang Y.; Wang C. Direct silylation reactions of inert C–H bonds via transition metal catalysis. Sci. China: Chem. 2015, 58, 1266–1279. 10.1007/s11426-015-5375-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Komiyama T.; Minami Y.; Hiyama T. Recent Advances in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Synthetic Transformations of Organosilicon Reagents. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 631–651. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sore H. F.; Galloway W. R. J. D.; Spring D. R. Palladium-catalysed cross-coupling of organosilicon reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1845–1866. 10.1039/C1CS15181A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gandhamsetty N.; Park S.; Chang S. Selective Silylative Reduction of Pyridines Leading to Structurally Diverse Azacyclic Compounds with the Formation of sp3 C–Si Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15176–15184. 10.1021/jacs.5b09209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wübbolt S.; Oestreich M. Catalytic Electrophilic C–H Silylation of Pyridines Enabled by Temporary Dearomatization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15876–15879. 10.1002/anie.201508181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fukumoto Y.; Hirano M.; Chatani N. Iridium-Catalyzed Regioselective C(sp3)–H Silylation of 4-Alkylpyridines at the Benzylic Position with Hydrosilanes Leading to 4-(1-Silylalkyl)pyridines. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3152–3156. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fukumoto Y.; Hirano M.; Matsubara N.; Chatani N. Ir4(CO)12-Catalyzed Benzylic C(sp3)–H Silylation of 2-Alkylpyridines with Hydrosilanes Leading to 2-(1-Silylalkyl)pyridines. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 13649–13655. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gandhamsetty N.; Joung S.; Park S.-W.; Park S.; Chang S. Boron-Catalyzed Silylative Reduction of Quinolines: Selective sp3 C–Si Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16780–16783. 10.1021/ja510674u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murai M.; Nishinaka N.; Takai K. Iridium-Catalyzed Sequential Silylation and Borylation of Heteroarenes Based on Regioselective C–H Bond Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5843–5847. 10.1002/anie.201801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bähr S.; Oestreich M. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution with Silicon Electrophiles: Catalytic Friedel–Crafts C–H Silylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 52–59. 10.1002/anie.201608470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen Q.-A.; Klare H. F. T.; Oestreich M. Bronsted Acid-Promoted Formation of Stabilized Silylium Ions for Catalytic Friedel-Crafts C–H Silylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7868–7871. 10.1021/jacs.6b04878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fang H.; Guo L.; Zhang Y.; Yao W.; Huang Z. A Pincer Ruthenium Complex for Regioselective C–H Silylation of Heteroarenes. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5624–5627. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Han Y.; Zhang S.; He J.; Zhang Y. B(C6F5)3-Catalyzed (Convergent) Disproportionation Reaction of Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7399–7407. 10.1021/jacs.7b03534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Han Y.; Zhang S.; He J.; Zhang Y. Switchable C–H Silylation of Indoles Catalyzed by a Thermally Induced Frustrated Lewis Pair. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8765–8773. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Klare H. F. T.; Oestreich M.; Ito J.-i.; Nishiyama H.; Ohki Y.; Tatsumi K. Cooperative Catalytic Activation of Si–H Bonds by a Polar Ru–S Bond: Regioselective Low-Temperature C–H Silylation of Indoles under Neutral Conditions by a Friedel–Crafts Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3312–3315. 10.1021/ja111483r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Liu W.-B.; Schuman D. P.; Yang Y.-F.; Toutov A. A.; Liang Y.; Klare H. F. T.; Nesnas N.; Oestreich M.; Blackmond D. G.; Virgil S. C.; Banerjee S.; Zare R. N.; Grubbs R. H.; Houk K. N.; Stoltz B. M. Potassium tert-Butoxide-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative C–H Silylation of Heteroaromatics: A Combined Experimental and Computational Mechanistic Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6867–6879. 10.1021/jacs.6b13031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Lu B.; Falck J. R. Efficient Iridium-Catalyzed CH Functionalization/Silylation of Heteroarenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 7508–7510. 10.1002/anie.200802456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Toutov A. A.; Liu W.-B.; Betz K. N.; Fedorov A.; Stoltz B. M.; Grubbs R. H. Silylation of C–H bonds in aromatic heterocycles by an Earth-abundant metal catalyst. Nature 2015, 518, 80 10.1038/nature14126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Yonekura K.; Iketani Y.; Sekine M.; Tani T.; Matsui F.; Kamakura D.; Tsuchimoto T. Zinc-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Silylation of Indoles. Organometallics 2017, 36, 3234–3249. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bähr S.; Oestreich M. The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation. Pure Appl. Chem. 2018, 90, 723–731. 10.1515/pac-2017-0902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Huo J.; Fu T.; Tan H.; Ye F.; Hossain M. L.; Wang J. Palladium(0)-catalyzed C(sp3)–Si bond formation via formal carbene insertion into a Si–H bond. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 11419–11422. 10.1039/C8CC06768F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer G. R.; Miller A. J. M.; Sherden N. H.; Gottlieb H. E.; Nudelman A.; Stoltz B. M.; Bercaw J. E.; Goldberg K. I. NMR Chemical Shifts of Trace Impurities: Common Laboratory Solvents, Organics, and Gases in Deuterated Solvents Relevant to the Organometallic Chemist. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2176–2179. 10.1021/om100106e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werkmeister S.; Fleischer S.; Zhou S.; Junge K.; Beller M. Development of New Hydrogenations of Imines and Benign Reductive Hydroaminations: Zinc Triflate as a Catalyst. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 777–782. 10.1002/cssc.201100633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bähr S.; Oestreich M. A Neutral RuII Hydride Complex for the Regio- and Chemoselective Reduction of N-Silylpyridinium Ions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5613–5622. 10.1002/chem.201705899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto T.; Fujii M.; Iketani Y.; Sekine M. Dehydrogenative Silylation of Terminal Alkynes with Hydrosilanes under Zinc–Pyridine Catalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 2959–2964. 10.1002/adsc.201200310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lummis P. A.; Momeni M. R.; Lui M. W.; McDonald R.; Ferguson M. J.; Miskolzie M.; Brown A.; Rivard E. Accessing Zinc Monohydride Cations through Coordinative Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9347–9351. 10.1002/anie.201404611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutsulyak D. V.; van der Est A.; Nikonov G. I. Facile Catalytic Hydrosilylation of Pyridines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1384–1387. 10.1002/anie.201006135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N. C.; Lyons J. E. Dihydropyridines from Silylation of Pyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 3396–3403. 10.1021/ja00966a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hirao K.; Iwakuma T.; Taniguchi M.; Abe E.; Yonemitsu O.; Date T.; Kotera K. Synthesis of ditwistane and bisnorditwistane. Novel ring systems. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1974, 17, 691–692. 10.1039/c39740000691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hirao K.; Iwakuma T.; Taniguchi M.; Yonemitsu O.; Date T.; Kotera K. Hydrogenation of cyclobutanes in strained cage compounds. Synthesis of ditwistane and bisnorditwistane (ditwistbrendane). J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1980, 163–169. 10.1039/p19800000163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Nakazaki M.; Naemura K.; Kondo Y.; Nakahara S.; Hashimoto M. Syntheses and chiroptical properties of optically active C1-methanotwistane, C2-ditwistane, C1-homobasketane, and C2-3,10-dehydroditwistane. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 4440–4444. 10.1021/jo01310a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ten Broeke J.; Douglas A. W.; Grabowski E. J. J. A symmetrical diazaditwistane. 2,9-Dicyano-5,11-dimethyl-5,11-diazatetracyclo[6.2.2.02,7.04,9]dodecane. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3159–3163. 10.1021/jo00881a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ten Broeke J.; Douglas A. W.; Kozlowski M. A.; Grabowski E. J. J. 5,11-Diazaditwistane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 49, 4303–4304. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)83491-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowicz K.; Wong Y.-S.; Chiaroni A.; Bénéchie M.; Marazano C. New Polycyclic Diamine Scaffolds from Dimerization of 3-Alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines in Acidic Medium. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 7780–7783. 10.1021/jo050937o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon H. L.; Jensen L. H. Crystal structure of the dimeric acid product of 1-methyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide. Acta Crystallogr. 1967, 23, 805–816. 10.1107/S0365110X67003731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn M. S.; Heinekey D. M.; Payne N. G.; Sofield C. D. Highly reactive dihydrogen complexes of ruthenium and rhenium: facile heterolysis of coordinated dihydrogen. Organometallics 1989, 8, 1824–1826. 10.1021/om00109a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nisa R. U.; Ayub K. Mechanism of Zn(OTf)2 catalyzed hydroamination-hydrogenation of alkynes with amines: insight from theory. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 5082–5090. 10.1039/C7NJ00312A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E.; Ukigai S.; Ito H. Boryl substitution of functionalized aryl-, heteroaryl- and alkenyl halides with silylborane and an alkoxy base: expanded scope and mechanistic studies. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2943–2951. 10.1039/C5SC00384A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Königs C. D. F.; Klare H. F. T.; Oestreich M. Catalytic 1,4-Selective Hydrosilylation of Pyridines and Benzannulated Congeners. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10076–10079. 10.1002/anie.201305028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-H.; Gutsulyak D. V.; Nikonov G. I. Chemo- and Regioselective Catalytic Reduction of N-Heterocycles by Silane. Organometallics 2013, 32, 4457–4464. 10.1021/om400269q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P. A.; Gray S. D.; Bruck M. A.; Wigley D. E. Tetrahydroquinolinyl Amido and Indolinyl Amido Complexes of Tantalum as Models for Substrate–Catalyst Adducts in Hydrodenitrogenation Catalysis. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 6027–6036. 10.1021/ic960298n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salembier H.; Mauldin J.; Hammond T.; Wallace R.; Alqassab E.; Hall M. B.; Perez L. M.; Chen Y.-J. A.; Turner K. E.; Bockoven E.; Brennessel W.; Chin R. M. Diruthenium Naphthalene and Anthracene Complexes Containing a Doubly Linked Dicyclopentadienyl Ligand. Organometallics 2012, 31, 4838–4848. 10.1021/om300384d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; b Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ditchfield R.; Hehre W. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. 10.1063/1.1674902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Francl M. M.; Pietro W. J.; Hehre W. J.; Binkley J. S.; Gordon M. S.; DeFrees D. J.; Pople J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654–3665. 10.1063/1.444267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hariharan P. C.; Pople J. A. The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. 10.1007/BF00533485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Rassolov V. A.; Pople J. A.; Ratner M. A.; Windus T. L. 6-31G* basis set for atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1223–1229. 10.1063/1.476673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Clark T.; Chandrasekhar J.; Spitznagel G. W.; Schleyer P. V. R. Efficient diffuse function-augmented basis sets for anion calculations. III. The 3-21+G basis set for first-row elements, Li–F. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4, 294–301. 10.1002/jcc.540040303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Krishnan R.; Binkley J. S.; Seeger R.; Pople J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c McLean A. D.; Chandler G. S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z = 11–18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. 10.1063/1.438980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Spitznagel G. W.; Clark T.; von Ragué Schleyer P.; Hehre W. J. An evaluation of the performance of diffuse function-augmented basis sets for second row elements, Na-Cl. J. Comput. Chem. 1987, 8, 1109–1116. 10.1002/jcc.540080807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanoi Y.; Nishihara H. Direct and Selective Arylation of Tertiary Silanes with Rhodium Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6671–6678. 10.1021/jo8008148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamze A.; Provot O.; Alami M.; Brion J.-D. Platinum Oxide Catalyzed Silylation of Aryl Halides with Triethylsilane: An Efficient Synthetic Route to Functionalized Aryltriethylsilanes. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 931–934. 10.1021/ol052996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CrysAlisPro V.CrysAlisPro, version 171.39.46; Rigaku Corporation: Oxford, U.K..

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT: Integrating space group determination and structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 70, C1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. L. PLATON SQUEEZE: a tool for the calculation of the disordered solvent contribution to the calculated structure factors. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 9–18. 10.1107/S2053229614024929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.