This cohort study analyzes self-reported use and risk factors of electronic cigarettes and other tobacco products by adolescents and young adults in the United States.

Key Points

Question

How has the use of JUUL among adolescents and young adults changed from 2018 to 2019?

Findings

In this nationally representative cohort study of adolescents and young adults, with 14 379 participants in 2018 and 12 114 participants in 2019, JUUL use increased in every age group but was highest among those aged 18 to 20 years and 21 to 24 years.

Meaning

Findings of this study suggest that urgent action is needed to curb youth use of electronic cigarettes and prevent a new generation from becoming addicted to nicotine.

Abstract

Importance

The increasing use rates of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) among young people in the United States have been largely associated with the emergence of high-nicotine-delivery device JUUL. Relevant data are needed to monitor e-cigarette, specifically JUUL, use to help inform intervention efforts.

Objective

To estimate the prevalence, patterns, and factors associated over time with e-cigarette use among adolescents and younger adults in the United States.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Two nationally representative longitudinal samples of adolescents and younger adults aged 15 to 34 years were drawn from the Truth Longitudinal Cohort, a national, probability-based cohort. Participants in this cohort were recruited through address-based sampling, and subsamples were recruited from a probability-based online panel. The present cohort study used data from follow-up online surveys, specifically, wave 7 (N = 14 379; collected from February 15, 2018, to May 25, 2018) and wave 8 (N = 12 114; collected from February 10, 2019, to May 17, 2019). Respondents reported their use of e-cigarettes, JUUL, and combustible tobacco products as well as their harm perceptions, household smoking status, sensation-seeking, friends’ e-cigarette use, and demographic information.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were ever and current (past 30 days) JUUL use. χ2 Analyses assessed differences in JUUL use by psychosocial and demographic characteristics. Logistic regression models identified the significant factors associated with wave 8 ever and current JUUL use among wave 7 e-cigarette–naive participants.

Results

A total of 14 379 participants (mean [SD] age, 24.3 [0.09] years; 8142 female [51.0%]) were included in wave 7 and 12 114 (mean [SD] age, 24.5 [0.10] years; 6835 female [50.1%]) in wave 8. JUUL use statistically significantly increased from wave 7 to wave 8 among ever users (6.0% [n = 1105] to 13.5% [2111]; P < .001) and current users (3.3% [680] to 6.1% [993]; P < .001). JUUL use increased among every age group and was highest among those aged 18 to 20 years (23.9% [491] ever users and 12.8% [340] current users) and 21 to 24 years (18.1% [360] ever users and 8.2% [207] current users). Users reported a higher prevalence of frequent use in wave 8 compared with wave 7 (37.6% vs 26.1%; P < .01). Significant factors associated with future JUUL use among e-cigarette–naive participants included younger age, combustible tobacco use, lower harm perceptions, sensation seeking, and friends’ e-cigarette use.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that the e-cigarette device JUUL appears to be associated with the youth e-cigarette epidemic, attracting new users and facilitating frequent use with their highly addictive nicotine content and appealing flavors. Findings of this study underscore the critical need for increased e-cigarette product regulation at the federal, state, and local levels.

Introduction

The rapid increase in the use of electronic or e-cigarettes among adolescents and younger adults continues to garner national attention and concern in the United States. Given that nearly all e-cigarettes contain nicotine,1 public health officials worry that rates of addiction to tobacco and other drugs will increase in young people, as early nicotine exposure can harm the brain and increase addiction susceptibility.2,3,4 A substantial body of evidence shows an association between e-cigarette use and future combustible tobacco use, with some research suggesting that young adult e-cigarette users are 4 times more likely to smoke cigarettes within 18 months compared with their nicotine-naive peers.5,6 In addition, recent vaping-related illnesses reported by more than 2000 individuals have led to 39 deaths.7 e-Cigarette use has been associated with not only lung problems but also adverse cardiovascular effects.8,9

The adverse effects of nicotine on adolescents and the enormous spikes in youths’ e-cigarette use have led the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to declare e-cigarette use in youths an epidemic.10,11,12 In 2017, 11% of high school students had used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days, according to the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS).13 By 2018, that number had risen to 20.8%, and by 2019, to 27.5%.13,14 Compared with the low-level use among adolescents in 2011 (1.5%), the recent increases represent more than 1800% growth in the number of users in just 8 years, especially between 2013 and 2015, when use rose from 4.5% to 16%, coinciding with the emergence of JUUL (JUUL Labs, Inc), a high-technology, nicotine-delivery device that quickly dominated the market.13,15,16 Today, e-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product among young people, surpassing cigarettes in popularity.10

A study by Monitoring the Future found that the increase in e-cigarette use among 10th and 12th graders from 2017 to 2018 was the largest the organization has ever recorded for any substance it has tracked in the past 44 years.11 Recently, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey also showed an increase in e-cigarette use among young adults aged 18 to 24 years, from 5.2% in 2014 to 7.6% in 2018.17 Although each of these national surveillance systems reported slightly different estimated prevalence rates, the rates reflect a considerable and troubling increase in use of these products by youths and young adults in the United States.

Evidence also suggests that young people are using e-cigarettes more frequently. Data from the NYTS indicated that the proportion of high school students who reported frequent e-cigarette use (>20 days per month) has increased substantially from 20.0% in 2017 to 27.7% in 2018 and 34.2% in 2019.13,14 This increase in use frequency may be associated with greater nicotine dependence among users.

Currently, JUUL accounts for 64.4% of e-cigarette dollar sales and 53.1% of e-cigarette unit sales according to Nielsen data.18 JUUL’s novel design uses nicotine salts, which deliver a high concentration of nicotine and allow the user to inhale the aerosol with less irritation.2,19 JUUL’s success has prompted other e-cigarette brands to adopt its nicotine salt delivery mechanism. By fall 2018, two-thirds of e-cigarette products contained nicotine concentrations similar to that in JUUL (5%-6%).1,20

Because of JUUL’s market dominance and popularity among teenagers and young adults, monitoring its use is critical to informing intervention efforts. In 2018, research from a large, longitudinal panel found that nearly 10% of adolescents aged 15 to 17 years and 11% of young adults aged 18 to 21 years reported being ever users of JUUL.21 The study also found that those aged 15 to 17 years had 16 times greater odds of being current JUUL users compared with those aged 25 to 34 years, and that one-quarter of all current users used JUUL on 10 or more of the past 30 days. Use was more common among certain demographics, such as those of white race/ethnicity and those with greater financial security. Use was also associated with psychosocial characteristics, including lower e-cigarette harm perceptions, high sensation seeking, and current use of combustible cigarettes.21

Given the volatility of the e-cigarette marketplace in the United States and JUUL’s recent emergence and dominance, rapid data are needed to ascertain which specific populations are using e-cigarette products to inform public health policy and practice. Therefore, the present cohort study sought to examine the prevalence of JUUL use from 2018 to 2019 using a large, nationally representative, probability-based sample of adolescents and younger adults aged 15 to 34 years. This study also explored the demographic and psychosocial correlates of JUUL use in 2019 among those who had never used an e-cigarette in 2018 to assess how these products may play a role in the trajectories of tobacco use over time.

Methods

Study Sample

The study sample was obtained from the Truth Longitudinal Cohort, a national, probability-based cohort that was established to evaluate the national tobacco prevention mass media campaign known as truth. The Truth Longitudinal Cohort sampling methods have been described elsewhere.22 Briefly, participants were recruited through address-based sampling, with follow-up online surveys (waves) every 6 months. Wave 1 was collected between April 21, 2014, and August 10, 2014. At baseline, the weighted response rate for the cohort was 38.7%, with quota limits for those aged 18 to 21 years.23

The analytic sample for this study included data from waves 7 and 8, the only 2 waves that included questions about JUUL. Wave 7 was conducted from February 15, 2018, to May 25, 2018, and comprised all participants from the Truth Longitudinal Cohort (n = 9149) and 1 refreshment sample (n = 5230) of participants aged 15 to 34 years, for a total sample of 14 379.21 Wave 8 was conducted from February 10, 2019, to May 17, 2019, and comprised participants from the Truth Longitudinal Cohort (n = 11 672) and 1 refreshment sample (n = 442), for a total sample of 12 114.

All data collection was conducted through a web portal, and participants were recruited from an address-based probability sample, with the data collection conducted online.24 For the logistic regression models, only e-cigarette-naive participants from wave 7 were included. The retention rate from wave 7 to wave 8 was 91.6% (n = 6165). Small differences were found among those who dropped out of the sample between wave 7 and wave 8 (ie, slightly younger, more likely to be current smokers, and higher sensation-seeking), but nonresponse adjustments were included in the final analytic weights. All data were weighted to be nationally representative of US residents aged 15 to 34 years.

The study protocol was approved by the Advarra institutional review board. Written informed consent was provided by all participants aged 18 years or older and by all parent or guardian of participants aged 15 to 17 years.

Measures

Ever use of e-cigarettes was measured by the item, “Have you ever tried using an e-cigarette/vape (even 1 or 2 puffs)?” with a response option of 1 for yes and 0 for no. Past 30-day use of e-cigarettes was measured by the item, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use an e-cigarette/vape?” Current use was defined as use of an e-cigarette or a vape (vaporizing device) at least once in the past 30 days.

Ever use of JUUL was measured among ever users of e-cigarettes with the item, “Have you ever used or tried a JUUL vape?” with a response option of 1 for yes and 0 for no. Current use of JUUL was defined as use of the device in the past 30 days and was measured with the item, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke a JUUL vape?” Participants were asked to report the number of days between 0 and 30, which were recoded into 1 of 3 categories on the basis of the distribution of the responses (1-2 days, 3-9 days, or 10-30 days).21

Combustible tobacco use status was categorized as 0 for never users, 1 for former users, and 2 for current users. Participants were considered current users of combustible tobacco products if they used (even 1 or 2 puffs) any of the following products in the past 30 days: cigarettes; large cigars, little cigars, or cigarillos; hookah, shisha, or waterpipe (with tobacco); and pipe (with tobacco).21 Former users of combustible tobacco products were those who had ever used any of the 4 products but not in the past 30 days. Those who had never used any of the 4 products, even 1 or 2 puffs, were considered never users.

Relative harm perceptions of e-cigarettes compared with cigarettes were assessed with the item, “Compared to regular cigarettes, do you think that e-cigarettes, e-hookah, vape pens, hookah pens, and vape pipes (including JUUL) are…,” with a response option of 0 for less harmful, 1 for about the same harm, 2 for more harmful, or 3 for don’t know or refused to respond.21

Use of combustible tobacco and/or e-cigarettes in the household was assessed with the item, “Does anyone you live with currently smoke any of the following tobacco products some days or every day?” Response options included cigarettes; large cigars, little cigars, or cigarillos; hookah; e-cigarettes; e-hookah, e-cigars, vape pens, hookah pens, or vape pipes; and “no one I live with smokes any.” Responses were recoded as 0 for no one I live with smokes any, 1 for e-cigarettes only, 2 for combustibles only, and 3 for both e-cigarettes and combustibles.

The construct of sensation seeking was measured at baseline by the following items: (1) “I would like to explore strange places”; (2) “I would like to take off on a trip with no preplanned routes or timetables”; (3) “I like to do frightening things”; (4) “I like wild parties”; (5) “I like new and exciting experiences, even if I have to break the rules”; (6) “I get restless when I spend too much time at home”; (7) “I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable”; and (8) “I would like to try parachute-jumping.” Response options ranged from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree, and the mean score of these items was calculated and treated as a continuous variable.21,25

Participants were asked, “How many of your 4 closest friends use e-cigarettes, pod mods, e-hookahs, e-cigars, vape pens, hookah pens, or tank system/box mod vaporizers?” Participants entered the number of friends between 0 and 4, and this item was treated as continuous.

The following demographic characteristics were measured: age group (15-17 years, 18-20 years, 21-24 years, or 25-34 years), sex (female or male), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), perceived financial situation (living comfortably, meeting needs with a little left over, just meeting basic expenses with nothing left over, or not meeting basic expenses), region (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West), and sexual orientation (heterosexual or straight, lesbian, gay, or bisexual). The first category listed in all categorical control variables was used as the reference group, with the exception of age group (25-34 years was the reference category).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in Stata SE, version 15.1, with the svy extension package for weighting (StataCorp LLC).26 Statistical significance was set to 2-sided P = .05, and all tests were 2-tailed. Descriptive and χ2 statistics assessed the prevalence of ever and current JUUL use among the full wave 8 sample and by combustible tobacco use, psychosocial characteristics, and demographic characteristics. Frequency of ever, current, and categorical last-30-day JUUL use by demographics in wave 8 was compared with the frequency in wave 7 using 2-tailed, independent sample t tests.

Multivariable logistic regression models assessed the ever and current use of JUUL in wave 8 among the e-cigarette–naive participants in wave 7, controlling for the wave 7 combustible tobacco use status as well as all psychosocial and demographic characteristics. Models used poststratification weights to generalize to the US population of 15- to 34-year-olds.22 Missing data were listwise deleted (n = 6644).

Results

A total of 14 379 participants (mean [SD] age, 24.3 [0.09] years; 8142 female [51.0%]) were included in wave 7 and 12 114 (mean [SD] age, 24.5 [0.10] years; 6835 female [50.1%]) in wave 8. Table 1 presents the demographic and psychosocial characteristics of the wave 7 and wave 8 samples. The participants were predominantly white, living comfortably or meeting their needs with a little left over, heterosexual, and from the South. Owing to the larger age range, the group aged 25 to 34 years represented half of the population estimates.

Table 1. Weighted Demographics and Psychosocial Characteristics of Wave 7 and Wave 8 Participants.

| Variable | No. (Weighted %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 7 | Wave 8 | |

| Overall | 14 379 | 12 114 |

| Age, y | ||

| 15-17 | 1861 (16.7) | 929 (15.4) |

| 18-20 | 3712 (14.8) | 2607 (14.0) |

| 21-24 | 5921 (20.8) | 5082 (19.5) |

| 25-34 | 2885 (47.9) | 3496 (51.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 9201 (55.9) | 7841 (55.4) |

| Black/African American, non-Hispanic | 1302 (13.4) | 1106 (13.3) |

| Hispanic | 2297 (21.2) | 1808 (21.2) |

| Other | 1552 (9.5) | 1359 (10.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 8142 (51.0) | 6835 (50.1) |

| Male | 6232 (49.1) | 5272 (49.9) |

| Perceived financial situationa | ||

| Living comfortably | 5231 (38.8) | 4198 (38.4) |

| Meeting needs with a little left over | 5586 (38.5) | 4834 (38.5) |

| Just meeting basic expenses with nothing left over | 2626 (17.4) | 2331 (17.7) |

| Not meeting basic expenses | 847 (5.4) | 716 (5.4) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual or straight | 12 314 (91.6) | 10 330 (91.6) |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual | 1321 (8.4) | 1186 (8.4) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 2985 (17.4) | 2595 (17.2) |

| South | 4820 (37.6) | 4048 (37.6) |

| Midwest | 3722 (21.2) | 3099 (21.1) |

| West | 2787 (23.8) | 2324 (24.1) |

| Combustible use statusb | ||

| Never | 7289 (48.6) | 5870 (48.4) |

| Former | 4925 (34.9) | 4560 (37.4) |

| Current | 2164 (16.6) | 1681 (14.3) |

| e-Cigarette vs cigarette harm perceptionc | ||

| Less harmful | 6400 (40.1) | 4362 (32.8) |

| About the same | 4303 (30.7) | 4496 (38.4) |

| More harmful | 1715 (12.4) | 2303 (18.2) |

| Don't know/refused to respond | 1961 (16.9) | 953 (10.6) |

| Household smoking status | ||

| No one I live with smokes any | 11 148 (77.3) | 9425 (78.8) |

| Only e-cigarettes, e-hookah, e-cigars, vape pens, or vape pipes | 594 (3.6) | 685 (4.7) |

| Only cigarettes or cigars | 2042 (16.0) | 1446 (13.4) |

| Both e-cigarettes and cigarettes or cigars | 459 (3.0) | 426 (3.1) |

| Sensation seeking, mean (SE)d | 2.89 (0.01) | 2.85 (0.01) |

| Friend e-cigarette use, mean (SE)e | NA | 0.54 (0.01) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Perceived financial situation was measured with the item, “Considering all income earners in your family/your own income and the income from any other people who help you, how would you describe your family’s/your own overall financial situation, would you say you….”

Combustible tobacco product use status was measured by the participants’ report of ever and past 30-day use of any combustible tobacco product (cigarettes, large cigars, little cigars, cigarillos, hookah, and pipe [with tobacco]). Those who reported never using any product were coded as 0 = never; reported ever using any product but not using any product in the past 30 days were coded as 1 = former; and reported using any product in the past 30 days were coded as 2 = current.

e-Cigarette harm perception was measured with the item, “Compared to regular cigarettes, do you think that e-cigarettes, e-hookah, vape pens, hookah pens and vape pipes (including JUUL) are….”

Sensation seeking was measured by calculating the mean of the following items: (1) “I would like to explore strange places”; (2) “I would like to take off on a trip with no preplanned routes or timetables”; (3) “I like to do frightening things”; (4) “I like wild parties”; (5) “I like new and exciting experiences, even if I have to break the rules”; (6) “I get restless when I spend too much time at home”; (7) “I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable”; and (8) “I would like to try parachute-jumping.” The response options were 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

Not measured in wave 7.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of ever and current use of e-cigarette and JUUL, as well as use by demographic and psychosocial characteristics among the wave 8 participants. Overall, 33.2% (n = 4951) of the wave 8 sample reported ever use of any e-cigarette, including JUUL, and 12.4% (1701) reported current use. Ever and current e-cigarette use differed by demographic correlates. Among the wave 8 respondents, 13.5% (2111) had ever used JUUL, and 6.1% (993) had used JUUL in the past 30 days. Significant differences in ever and current JUUL use were observed by age, race/ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, and region. JUUL use was highest among young adults aged 18 to 20 years (23.9% [665] ever users and 12.8% [349] current users) and 21 to 24 years (18.1% [938] ever users and 8.2% [430] current users). Use was lowest among adults aged 25 to 34 years, with 8.2% (356) reporting ever use of JUUL and 2.9% (135) reporting current use of the product.

Table 2. Weighted Ever and Current JUUL Use Among Wave 8 Participants by Demographic Characteristics.

| Variable | JUUL Use | e-Cigarette Use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evera | Currentb | Everc | Currentd | |||||

| Weighted % | P Valuee | Weighted % | P Valuee | Weighted % | P Valuee | Weighted % | P Valuee | |

| Overall (n = 12 114) | 13.5 | NA | 6.1 | NA | 33.2 | NA | 12.4 | NA |

| Age group, y | ||||||||

| 15-17 (n = 929) | 15.9 | <.001 | 7.8 | <.001 | 23.0 | <.001 | 10.9 | <.001 |

| 18-20 (n = 2607) | 23.9 | 12.8 | 40.4 | 21.8 | ||||

| 21-24 (n = 5083) | 18.1 | 8.2 | 46.1 | 16.7 | ||||

| 25-34 (n = 3496) | 8.2 | 2.9 | 29.3 | 8.6 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic (n = 7841) | 14.4 | .01 | 6.6 | .04 | 33.2 | .15 | 12.4 | .03 |

| Black or African American, non-Hispanic (n = 1106) | 9.2 | 4.5 | 32.4 | 11.7 | ||||

| Hispanic (n = 1808) | 14.6 | 6.8 | 35.7 | 14.4 | ||||

| Other (n = 1359) | 11.9 | 3.7 | 29.0 | 8.9 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female (n = 6835) | 12.4 | .03 | 5.1 | .005 | 32.4 | .30 | 10.9 | .002 |

| Male (n = 5272) | 14.7 | 7.0 | 34.0 | 13.9 | ||||

| Perceived financial situationf | ||||||||

| Living comfortably (n = 4198) | 13.7 | .06 | 6.1 | .60 | 29.2 | <.001 | 10.4 | .001 |

| Meeting needs with a little left over (n = 4834) | 13.3 | 6.0 | 33.7 | 12.6 | ||||

| Just meeting basic expenses with nothing left over (n = 2331) | 12.0 | 5.8 | 38.5 | 15.8 | ||||

| Not meeting basic expenses (n = 716) | 19.1 | 8.1 | 41.7 | 14.6 | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Heterosexual or straight (n = 10 330) | 12.8 | .002 | 5.6 | .006 | 31.7 | <.001 | 11.5 | <.001 |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual (n = 1186) | 18.1 | 8.9 | 48.7 | 19.9 | ||||

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast (n = 2595) | 17.1 | .02 | 7.8 | .04 | 34.7 | .45 | 12.9 | .27 |

| South (n = 4048) | 12.6 | 5.4 | 31.7 | 11.8 | ||||

| Midwest (n = 3099) | 13.2 | 7.0 | 34.2 | 14.0 | ||||

| West (n = 2324) | 12.8 | 5.1 | 33.3 | 11.6 | ||||

| Combustible use statusg | ||||||||

| Never (n = 5870) | 6.6 | <.001 | 2.5 | <.001 | 10.4 | <.001 | 4.3 | <.001 |

| Noncurrent (n = 4560) | 15.1 | 5.3 | 46.2 | 12.8 | ||||

| Current (n = 1681) | 32.6 | 20.3 | 76.3 | 38.7 | ||||

| e-Cigarette vs cigarette harm perceptionh | ||||||||

| Less harmful (n = 4362) | 21.6 | <.001 | 12.4 | <.001 | 49.4 | <.001 | 24.8 | <.001 |

| About the same (n = 4496) | 10.0 | 3.3 | 26.0 | 6.9 | ||||

| More harmful (n = 2303) | 10.7 | 3.1 | 24.7 | 5.9 | ||||

| Don't know or refused to respond (n = 953) | 5.86 | 1.7 | 23.4 | 5.0 | ||||

| Household smoking status | ||||||||

| No one I live with smokes any (n = 9425) | 10.8 | <.001 | 3.87 | <.001 | 27.1 | <.001 | 7.9 | <.001 |

| Only e-cigarettes (n = 685) | 34.8 | 23.5 | 76.4 | 51.8 | ||||

| Only cigarettes or cigars (n = 1446) | 18.2 | 9.6 | 45.9 | 17.1 | ||||

| Both e-cigarettes and cigarettes or cigars (n = 426) | 33.6 | 22.1 | 71.4 | 44.3 | ||||

| Sensation seeking, mean (SE)i | 3.3 (0.03) | NA | 3.3 (0.04) | NA | 3.2 (0.02) | NA | 3.2 (0.03) | NA |

| Friend e-cigarette use, mean (SE) | 1.5 (0.06) | NA | 2.2 (0.07) | NA | 1.1 (0.03) | NA | 1.9 (0.05) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Ever JUUL use defined as the yes response to the item, “Have you ever used or tried a JUUL vape?”

Current JUUL use defined as use in the past 30 days.

Ever e-cigarette use defined as the yes response to the item, “Have you ever used or tried using an e-cigarette/vape?”

Current e-cigarette use defined as use in the past 30 days.

Calculated using the χ2 test.

See footnote a in Table 1.

See footnote b in Table 1.

See footnote c in Table 1.

See footnote d in Table 1.

Use was also highest among participants who were Hispanic (14.6% [310] ever users and 6.8% [138] current users) or white (14.4% [1466] ever users and 6.6% [707] current users); men (14.7% [989] ever users and 7.0% [500] current users); identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (18.1% [290] ever users and 8.9% [130] current users); and lived in the Northeast (17.1% [555] ever users and 7.8% [255] current users). Ever JUUL use was highest among current combustible product users (32.6% [658]), followed by former combustible product users (15.1% [1065]). Current JUUL use trends were similar, with 20.3% (415) of current combustibles users and 5.3% (432) of former combustibles users reporting current use of JUUL. Rates of JUUL use differed by household smoking status and e-cigarette harm perceptions. Participants who believed that e-cigarettes were less harmful than cigarettes had the highest rates of ever use (21.6% [1160]) and current use (12.4% [617]) of JUUL. Those living in homes where someone used e-cigarettes and those living with someone who used both e-cigarettes and combustible products reported the highest rates of ever use (34.8% [310] only e-cigarettes; 33.6% [176] both e-cigarette and combustibles) and current use (23.5% [213] only e-cigarettes; 22.1% [176] both e-cigarettes and combustibles) of JUUL. Ever JUUL users had a sensation-seeking rating of 3.27 (SE = 0.03), and current JUUL users had a rating of 3.32 (SE = 0.04). On average, among their 4 closest friends, 1.5 (SE = 0.06) friends of ever JUUL users currently used e-cigarettes, and 2.2 (SE = 0.07) friends of current JUUL users currently used e-cigarettes.

Table 3 presents changes in the prevalence of e-cigarette and JUUL use from wave 7 to wave 8. Ever use of e-cigarettes significantly increased from wave 7 to wave 8 (29.6% [4958] to 33.2% [4951]; P < .001), as did current e-cigarette use (10.1% [1875] to 12.4% [1701]; P < .001). Increases in ever and current e-cigarette use differed by demographic correlates. Overall, ever JUUL use increased by 123.7% from wave 7 to wave 8 (6.0% [1105] to 13.5% [2111]; P < .001). Similarly, current JUUL use increased by 82.9% from wave 7 to 8 (3.3% [680] to 6.1% [993]; P < .001). Ever JUUL use rates significantly increased in each age, and current JUUL use rates significantly increased for those aged 18 to 20 years, 21 to 24 years, and 25 to 34 years. Ever and current JUUL use significantly increased for both male and female participants. Ever JUUL use significantly increased for participants in all racial and ethnic groups; however, current JUUL use rates significantly increased for whites and Hispanic respondents. Ever and current JUUL use significantly increased across all perceived financial situations.

Table 3. Comparison of Weighted Ever and Current JUUL Use Among Wave 7 and Wave 8 Participants.

| Variable | Ever JUUL Usea | Current JUUL Useb | Ever e-Cigarette Usec | Current e-Cigarette Used | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 7 | Wave 8 | % Change | P Valuee | Wave 7 | Wave 8 | % Change | P Valuee | Wave 7 | Wave 8 | % Change | P Valuee | Wave 7 | Wave 8 | % Change | P Valuee | |

| Overall | 6.0 | 13.5 | 123.7 | <.001 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 82.9 | <.001 | 29.6 | 33.2 | 12.3 | <.001 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 22.8 | <.001 |

| Age group, y | ||||||||||||||||

| 15-17 | 9.5 | 15.9 | 67.4 | <.001 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 28.3 | .17 | 18.2 | 23.0 | 26.1 | .01 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 3.2 | .82 |

| 18-20 | 11.9 | 23.9 | 100.8 | <.001 | 8.4 | 12.8 | 34.4 | <.001 | 37.1 | 40.4 | 8.9 | .05 | 16.9 | 21.9 | 29.9 | <.001 |

| 21-24 | 5.6 | 18.1 | 223.2 | <.001 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 60.97 | <.001 | 40.2 | 46.1 | 14.7 | <.001 | 12.0 | 16.7 | 31.2 | <.001 |

| 25-34 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 154.8 | <.001 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 245.4 | <.001 | 26.6 | 29.3 | 10.3 | 0.11 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 22.9 | .12 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 6.6 | 14.4 | 117.1 | <.001 | 3.7 | 6.6 | 76.6 | <.001 | 30.1 | 33.2 | 10.2 | .02 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 20.7 | .009 |

| Black or African American, non-Hispanic | 3.5 | 9.2 | 160.9 | <.001 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 99.0 | .06 | 26.8 | 32.4 | 21.0 | .04 | 9.4 | 11.7 | 25.0 | .21 |

| Hispanic | 6.4 | 14.6 | 127.2 | <.001 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 114.8 | <.001 | 31.4 | 35.7 | 13.6 | .06 | 11.0 | 14.4 | 30.5 | .03 |

| Other | 5.2 | 11.9 | 128.8 | <.001 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 37.0 | .17 | 26.2 | 29.0 | 10.7 | .35 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 12.7 | .53 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 5.6 | 12.4 | 122.8 | <.001 | 2.9 | 5.1 | 80.1 | <.001 | 28.5 | 32.4 | 13.6 | .003 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 22.8 | .007 |

| Male | 6.5 | 14.6 | 124.0 | <.001 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 84.2 | <.001 | 30.6 | 34.0 | 10.8 | .02 | 11.4 | 13.9 | 22.2 | .01 |

| Perceived financial situationf | ||||||||||||||||

| Living comfortably | 6.8 | 13.7 | 101.1 | <.001 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 38.8 | .005 | 24.1 | 29.2 | 21.3 | .001 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 17.6 | .09 |

| Meeting needs with a little left over | 5.6 | 13.3 | 136.8 | <.001 | 2.4 | 6.0 | 149.0 | <.001 | 31.5 | 33.7 | 7.2 | .16 | 9.8 | 12.6 | 29.4 | .004 |

| Just meeting basic expenses with nothing left over | 5.2 | 12.0 | 129.1 | <.001 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 72.7 | .02 | 35.4 | 38.5 | 9.0 | .21 | 12.1 | 15.8 | 30.7 | .03 |

| Not meeting basic expenses | 5.8 | 19.1 | 231.3 | <.001 | 2.7 | 8.10 | 195.7 | .001 | 37.6 | 41.7 | 11.0 | .34 | 15.9 | 14.6 | −7.9 | .69 |

Ever JUUL use defined as the yes response to the item, “Have you ever used or tried a JUUL vape?”

Current JUUL use defined as use in the past 30 days.

Ever e-cigarette use defined as the yes response to the item, “Have you ever used or tried using an e-cigarette/vape?”

Current e-cigarette use defined as use in the past 30 days.

Calculated using independent-sample t test comparing prevalence in wave 7 group with that in wave 8 group.

See footnote a in Table 1.

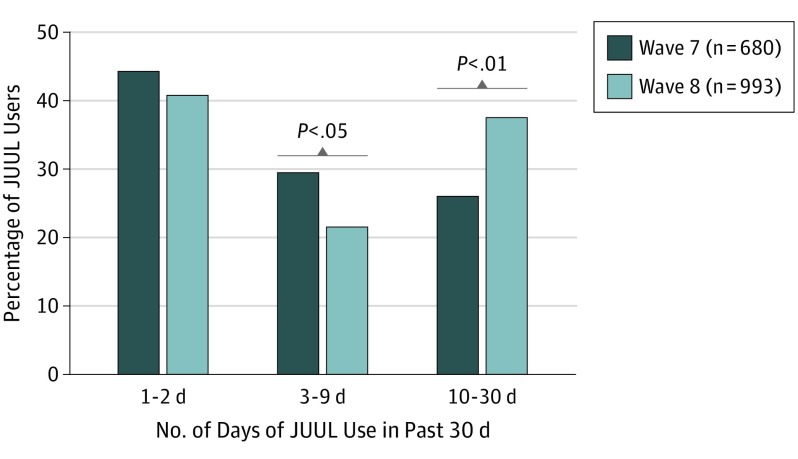

Frequency of past 30-day use for waves 7 and 8 current JUUL users can be found in the Figure. Compared with wave 7 (29.6% [177]), fewer respondents used JUUL for 3 to 9 days in wave 8 (21.6% [231]; P < .05). However, a larger proportion used JUUL for 10 to 30 days in wave 8 compared with wave 7 (37.6% [345] vs 26.1% [177]; P < .01). These trends were similar in each age group.

Figure. Comparison of Use Frequency Among Current JUUL Users in Wave 7 and Wave 8 Participants.

Logistic regression models of ever and current JUUL use among wave 7 e-cigarette-naive participants are presented in Table 4. Compared with those aged 25 to 34 years, all younger age groups had higher odds of ever use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] range = 1.82-4.91; P < .05) and current use (aOR range = 10.11-20.64; P < .01) of JUUL. Compared with those who were never smokers at wave 7, former and current smokers were more likely to have ever used JUUL (aOR range = 2.20-3.60; P < .01) or to be current JUUL users (aOR range = 2.22-3.03; P < .05). Those with higher e-cigarette harm perceptions had lower odds of current JUUL use (aOR range = 0.32-0.42; P < .05). Increased sensation-seeking was also statistically significantly associated with greater odds of ever use (aOR = 1.75; P < .01) and current use (aOR = 1.94; P < .01) of JUUL. Those with more friends who were users of e-cigarettes had greater odds of ever using JUUL (aOR = 1.84; P < .01) and of currently using JUUL (aOR = 2.53; P < .01).

Table 4. Estimated Wave 8 Ever and Current JUUL Use Among Wave 7 e-Cigarette-Naive Participants.

| Variable | JUUL Use, aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Evera | Currentb | |

| Age group, y | ||

| 15-17 | 3.95 (2.20-7.11)c | 18.95 (5.90-60.85)c |

| 18-21 | 4.91 (2.93-8.21)c | 20.64 (7.182-59.343)c |

| 22-24 | 1.82 (1.13-2.94)d | 10.11 (3.76-27.21)c |

| 25-34 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black/African American, non-Hispanic | 0.78 (0.40-1.52) | 0.48 (0.14-1.59) |

| Hispanic | 0.99 (0.62-1.58) | 0.84 (0.37-1.92) |

| Other | 0.87 (0.44-1.75) | 0.33 (0.14-0.79)d |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 0.88 (0.60-1.30) | 0.99 (0.55-1.79) |

| Perceived financial statuse | ||

| Living comfortably | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Meeting needs with a little left over | 0.97 (0.64-1.46) | 0.77 (0.39-1.49) |

| Just meeting basic expenses with nothing left over | 0.71 (0.44-1.16) | 0.58 (0.27-1.22) |

| Not meeting basic expenses | 1.49 (0.46-4.88) | 0.65 (0.239-1.78) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual or straight | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Lesbian, gay, or bisexual | 0.91 (0.57-1.46) | 1.14 (0.47-2.78) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| South | 0.89 (0.56-1.44) | 1.10 (0.56-2.14) |

| Midwest | 0.71 (0.42-1.21) | 0.87 (0.41-1.84) |

| West | 0.85 (0.49-1.47) | 1.04 (0.50-2.18) |

| Wave 7 combustible use statusf | ||

| Never | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Former | 2.20 (1.38-3.51)c | 2.22 (1.22-4.03)c |

| Current | 3.60 (1.80-7.18)c | 3.03 (1.258-7.30)d |

| e-Cigarette vs cigarette harm perceptiong | ||

| Less harmful | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| About the same | 0.78 (0.51-1.17) | 0.42 (0.23-0.74)c |

| More harmful | 0.90 (0.55-1.48) | 0.32 (0.13-0.78)d |

| Don't know/refused to respond | 0.56 (0.26-1.21) | 0.23 (0.05-1.20) |

| Household smoking status | ||

| No one I live with smokes any | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Only e-cigarettes | 1.05 (0.61-1.83) | 1.99 (0.95-4.17) |

| Only combustibles | 1.00 (0.58-1.71) | 1.55 (0.75-3.19) |

| Both e-cigarettes and combustibles | 0.72 (0.36-1.44) | 0.97 (0.35-2.70) |

| Sensation seekingh | 1.75 (1.38-2.22)c | 1.94 (1.44-2.62)c |

| Friend e-cigarette use | 1.84 (1.59-2.12)c | 2.53 (2.05-3.11)c |

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Ever JUUL use defined as the yes response to the item, “Have you ever used or tried a JUUL vape?”

Current JUUL use defined as use in the past 30 days.

P < .01.

P < .05.

See footnote a in Table 1.

See footnote b in Table 1.

See footnote c in Table 1.

See footnote d in Table 1.

Discussion

This longitudinal cohort study found that JUUL was associated with the soaring increase in e-cigarette use among adolescents and young adults. Findings were consistent with national sales data that demonstrate the dominant role of JUUL in this product category. Over the time of this study, when the ever use of JUUL among teenagers and young adults more than doubled in a single year, JUUL captured more than 70% of e-cigarette market sales.27 Although JUUL use increased in every age group, it remained most popular among adolescents and young adults, especially among those aged 18 to 24 years.

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence that use of an e-cigarette, particularly JUUL, is becoming an accepted part of youth culture. The increase in ever use from 6.1% in 2018 to 13.5% in 2019 for those aged 15 to 34 years represents an unprecedented increase in tobacco product use among young people in the United States. Moreover, these data showed that JUUL use prompted frequent use, suggesting its high abuse potential. Claims that youths only experiment or use JUUL infrequently do not appear to be supported by documented patterns in JUUL use over the past 2 years.

Despite claims that e-cigarettes, including JUUL, are for adults only, evidence showed that e-cigarette manufacturers actively targeted young people through social media and other youth-friendly outlets.28,29 In fact, in the present study, use among younger participants (23.9% ever vs 12.8% current users) was substantially higher compared with use among older participants (8.2% ever vs 2.9% current users), likely reflecting the promotional efforts of the tobacco industry. In addition, JUUL’s array of youth-appealing flavors, including mango, fruit medley, and cucumber, was likely associated with greater JUUL use during the period in which data were collected. Youth e-cigarette users commonly cited flavors as a top reason for e-cigarette initiation, second only to use by a family member or friend.30 According to the FDA, among current youth e-cigarette users, 97% used a flavored e-cigarette in the past month.31 Although JUUL has removed some flavors from retail stores, recent analyses showed that young users were simply switching to flavors that were still available. Preliminary 2019 NYTS data showed that mint and menthol e-cigarette use increased to 63.9% from 51.2% in 2018 among high school students, suggesting these users switched to mint when mango and fruit medley became harder to obtain.32,33 Although the models in the present study indicated that current and former users of combustible tobacco products were more likely to use JUUL, our analyses (not presented) revealed that approximately half of JUUL users aged 15 to 17 years reported never using combustible products, which suggests that JUUL appeals to young people at low risk for tobacco use initiation. Although e-cigarettes have the potential to reduce harm among committed smokers, relatively few adults used JUUL to quit.34 Among those aged 18 to 24 years, only 1 in 5 JUUL users reported trying the product to quit cigarette smoking.34

State and local governments are central to tobacco control, serving as learning laboratories for how to establish and implement successful tobacco control policies. Recently, state and local officials have begun to regulate and restrict promotional efforts and flavored e-cigarette products. Several governors have temporarily banned in-store and online sales of flavored e-cigarettes in their states, including Michigan, Montana, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington.35,36,37,38,39,40 Although some bans have temporarily been halted (New York, Michigan, and Oregon), there appears to be progress at the state level to fill the gap created by FDA inaction.41,42,43 Other governmental efforts include judicial action against JUUL in North Carolina, an e-cigarette ban in San Francisco, California, and Massachusetts, and an FDA mandate for e-cigarette manufacturers to comply with federal regulations.44,45,46,47 However, more action is needed to mitigate delays in federal policy and enforcement.

In July 2019, a US Congressional hearing examined JUUL’s role in the e-cigarette epidemic in youths and found that JUUL used marketing tactics and business practices that targeted young people.48 Although JUUL stated it will take steps to curb youths’ e-cigarette use, the company also hired more than 80 lobbyists to undermine tobacco control policies at the state level, including fighting bans on flavored e-cigarette pods, contesting legislation that would provide tighter regulation for vaping, and undercutting laws to prevent use among youths.49,50,51

The FDA prohibits sales of e-cigarettes to minors, but e-cigarette use among young people continues to escalate. The US government recently announced its intention to address the epidemic.33 In an encouraging first step to stem use among youths, the FDA reported that it would invoke the regulatory mechanism needed to remove flavored e-cigarettes from the market.4 We believe the FDA, however, can and should do much more. The 2017 delay by the FDA to enforce its authority to regulate e-cigarettes and require premarket review created the opportunity for JUUL to enter and dominate the marketplace. At a minimum, the FDA must comply with the 2019 federal ruling for e-cigarette companies to submit premarket authorization by May 2020.

After decades of declining use of combustible tobacco products, e-cigarettes, with their highly addictive nicotine content and appealing flavors, are threatening to hook a new generation on nicotine and tobacco products. Findings of this study underscore the critical need for increased e-cigarette product regulation at the federal, state, and local levels to help reduce access to, appeal of, and exposure to promotional efforts in order to protect society’s youngest and most vulnerable. States, in particular, play a key role in addressing the crisis by implementing policies to prevent youth use. We believe future research and regulation efforts must arrest the e-cigarette epidemic in order to prevent another generation from becoming lifelong tobacco users.

Strengths and Limitations

This cohort study has many strengths and some limitations. Similar to other studies, this study was not able to measure the amount or number of JUUL pods used by respondents. JUUL reported that 1 pod is equivalent to 1 pack of cigarettes, but the method to measure frequency exposure to these highly variable products remains unclear.2,20,52 Although the magnitude of our prevalence estimates of JUUL and e-cigarette use differed from estimates by national surveillance data such as the NYTS, Monitoring the Future, and the National Health Interview Survey, data from the Truth Longitudinal Cohort revealed similar trends of increased e-cigarette and JUUL use from 2018 to 2019 among young people. Despite these limitations, the study results appear to provide compelling empirical evidence of the trends in JUUL use over time and the factors associated with JUUL use.

Conclusions

This study found that JUUL use appeared to be associated with the higher rate of e-cigarette use among adolescents and young adults. JUUL use increased among every age group. Among those aged 15 to 34 years, ever use rose from 6.1% in 2018 to 13.5% in 2019. Use was highest among young adults aged 18 to 20 years and those aged 21 to 24 years, whereas use was lowest among adults aged 25 to 34 years. Users also reported a higher prevalence of frequent use in 2019 compared with 2018. These findings underscore the need for greater regulation of e-cigarettes.

References

- 1.Romberg AR, Miller Lo EJ, Cuccia AF, et al. . Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013-2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;203:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine Public Health Consequences of e-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olfson M, Wall MM, Liu S-M, Sultan RS, Blanco C. E-cigarette use among young adults in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):655-663. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koval R, Willett J, Briggs J. Potential benefits and risks of high-nicotine e-cigarettes. JAMA. 2018;320(14):1429-1430. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primack BA, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. . Initiation of traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among tobacco-naïve US young adults. Am J Med. 2018;131(4):443.e1-443.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. . Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700-707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Outbreak of lung illness associated with using e-cigarette products. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Updated November 21, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 8.Gotts JE, Jordt SE, McConnell R, Tarran R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ. 2019;366:l5275. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qasim H, Karim ZA, Rivera JO, Khasawneh FT, Alshbool FZ. Impact of electronic cigarettes on the cardiovascular system. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9):e006353. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. . Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157-164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018: volume I, secondary school students. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED589763. Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration FDA takes new steps to address epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, including a historic action against more than 1,300 retailers and 5 major manufacturers for their roles perpetuating youth access. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm620184.htm. Published September 11, 2018. Accessed September 17, 2018.

- 13.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1276-1277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. . e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019 [published online November 5, 2019]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, Holder-Hayes E, Jones CD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(45):1021-1026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. . Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361-367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Health Interview Survey: 2018 data release. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2018_data_release.htm. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 18.Herzog B, Kanada P Cig vol declines moderately. Nielsen: Tobacco All Channel Data Thru 10/5. San Francisco, CA: Wells Fargo Securities; October 15, 2019.

- 19.Jackler RK, Ramamurthi D. Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):623-628. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammond D, Reid JL, Rynard VL, et al. . Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: repeat national cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2019;365:l2219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallone DM, Bennett M, Xiao H, Pitzer L, Hair EC. Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):603-609. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantrell J, Hair EC, Smith A, et al. . Recruiting and retaining youth and young adults: challenges and opportunities in survey research for tobacco control. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):147-154. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Association for Public Opinion Research Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 8th ed Oakbrook Terrace, IL: AAPOR; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.GfK KnowledgePanel: a methodological overview. https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/US/documents/KnowledgePanel_-_A_Methodological_Overview.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- 25.Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32(3):401-414. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stata Statistical Software Release 15 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

- 27.Herzog B, Kanada P Cig vol declines moderate. Neilsen: Tobacco All Channel Data Thru 7/13. San Francisco, CA: Wells Fargo Securities; July 23, 2019.

- 28.Jackler RCC, Getachew B, Whitcomb M, et al. JUUL advertising over its first three years on the market. Stanford University. http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/publications/JUUL_Marketing_Stanford.pdf. Published January 31, 2019. Accessed June 28, 2019.

- 29.Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Herzog TA, et al. . Social media e-cigarette exposure and e-cigarette expectancies and use among young adults. Addict Behav. 2018;78:51-58. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, et al. . Reasons for electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(6):196-200. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Food and Drug Administration Modifications to compliance policy for certain deemed tobacco products. https://www.fda.gov/media/121384/download. Published March 2019. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html. Accessed October 2, 2019.

- 33.US Department of Health and Human Services Trump administration combating epidemic of youth e-cigarette use with plan to clear market of unauthorized, non-tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/09/11/trump-administration-combating-epidemic-youth-ecigarette-use-plan-clear-market.html. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed October 2, 2019.

- 34.Patel M, Cuccia A, Willett J, et al. . JUUL use and reasons for initiation among adult tobacco users. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):681-684. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montana.gov. Governor Bullock directs ban on flavored e-cigarettes to address public health emergency. http://governor.mt.gov/Pressroom/governor-bullock-directs-ban-on-flavored-e-cigarettes-to-address-public-health-emergency. Published October 8, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 36.Access Washington Inslee issues executive order to change how state will regulate vaping industry in light of recent health crisis. https://www.governor.wa.gov/news-media/inslee-issues-executive-order-change-how-state-will-regulate-vaping-industry-light-recent. Published September 27, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 37.Michigan.gov. Governor Whitmer takes bold action to protect Michigan kids from harmful effects of vaping. https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90640-506450--,00.html. Published September 4, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 38.New York State. Governor Cuomo announces emergency executive action to ban the sale of flavored e-cigarettes. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-emergency-executive-action-ban-sale-flavored-e-cigarettes. Published September 15, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 39.Oregon.gov. Governor Brown issues temporary ban on flavored vaping products, convenes Vaping Public Health Workgroup. https://www.oregon.gov/newsroom/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx?newsid=3448. Published October 4, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 40.Raimondo GM. Protecting Rhode Island youth against the harms of vaping. Executive order 19-09. http://www.governor.ri.gov/documents/orders/Executive-Order-19-09.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 41.Singh K. New York court blocks state ban on flavored e-cigarettes. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-vaping-new-york/new-york-court-blocks-state-ban-on-flavored-e-cigarettes-idUSKBN1WJ0IK. Published October 4, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 42.Michigan.gov. Governor Whitmer to seek Supreme Court ruling to protect Michigan kids, public health. https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90640-510074--,00.html. Published October 15, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 43.Peel S. Oregon Court of Appeals blocks flavored vaping ban for nicotine-containing vapes. https://www.wweek.com/news/state/2019/10/17/oregon-court-of-appeals-blocks-flavored-vaping-ban/. Published October 17, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 44.Fuller T. San Francisco bans sale of Juul and other e-cigarettes. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/25/us/juul-ban.html. Published June 25, 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

- 45.Karanth S. North Carolina becomes first state to sue Juul over e-cigarettes. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/north-carolina-lawsuit-juul_n_5cdc7582e4b066205c60cd88. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed May 30, 2019.

- 46.US District Court for the District of Maryland. Am. Acad. of Pediatrics v. Food & Drug Admin. Case No.: PWG-18-883 (D. Md. Jul. 12, 2019).

- 47.Mass.gov Guide: vaping public health emergency. https://www.mass.gov/guides/vaping-public-health-emergency. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 48.House Committee on Oversight and Reform Examining JUUL’s role in the youth nicotine epidemic: part II. https://oversight.house.gov/legislation/hearings/examining-juul-s-role-in-the-youth-nicotine-epidemic-part-ii. Published July 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

- 49.Kaplan S. In Washington, Juul vows to curb youth vaping. Its lobbying in states runs counter to that pledge. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/28/health/juul-lobbying-states-ecigarettes.html. Published April 28, 2019. Accessed November 4, 2019.

- 50.Glantz SA. Juul is trying to trick San Francisco voters into repealing laws they passed to protect San Franciscans from Juul. https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/juul-trying-trick-san-francisco-voters-repealing-laws-they-passed-protect-san-franciscans-juul. Published May 16, 2019. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- 51.Cai K. Juul readies backdoor plan to dodge San Francisco e-cigarette ban with November vote. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrickcai/2019/06/26/juul-readies-backdoor-plan-to-dodge-san-francisco-e-cigarette-ban-with-november-vote/#5697b4352671. Published June 26, 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

- 52.Goniewicz ML, Gupta R, Lee YH, et al. . Nicotine levels in electronic cigarette refill solutions: a comparative analysis of products from the U.S., Korea, and Poland. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(6):583-588. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]