Abstract

This study examines changes in the opioid prescription given in a single facility before and after a state law was passed restricting their use.

In 2017, more than 47 000 Americans died of opioid misuse and overdose.1 In response to this crisis, many states have signed into law new regulations regarding the prescribing of opioids for acute and chronic pain. Florida House Bill 21 (HB21),2 which went into effect on July 1, 2018, mandated the following changes (among others) to opioid prescribing: (1) a limit of a 3-day to 7-day supply of opioids for acute pain, (2) a prohibition of refills ordered with the initial opioid prescription for acute pain, and (3) a requirement that the prescribing physician or his or her delegate check Florida’s prescription drug–monitoring program prior to prescribing opioids. We sought to quantify the association of Florida HB21 with opioid prescribing for acute postoperative pain at our institution.

Methods

Using similar methodology from our prior work investigating opioid-prescribing patterns,3 we compared opioid prescribing at discharge from surgery at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, for 2 periods: July 1, 2017, through September 30, 2017 (pre-HB21; period 1), and July 1, 2018, through September 30, 2018 (post-HB21; period 2), across the same 25 procedures (total shoulder arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty, laparoscopic prostatectomy, laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, parotid gland excision, breast lumpectomy, parathyroidectomy, open initial inguinal hernia repair, laparoscopic initial inguinal hernia repair, lumbar laminotomy, lumbar laminectomy, tonsillectomy, vaginal hysterectomy, rotor-cuff repair, thyroid lobectomy, knee arthroscopic meniscectomy, carotid endarterectomy, total knee arthroplasty, laparoscopic low anterior resection, laparoscopic nephrectomy, thoracoscopic lung wedge resection, open ileocecectomy, open ventral hernia repair, and simple mastectomy). Opioid prescriptions were accessed through medication orders and converted to oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) using conversion factors provided by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.4 We investigated (1) whether the patient received any opioids at discharge (yes or no), (2) the number of OMEs at discharge, and (3) whether the patient received more than 200 OMEs at discharge (approximately 1 tablet of 5 mg of oxycodone every 6 hours for 7 days).3 This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Mayo Clinic. A waiver of consent was granted because the study was considered to be a quality-improvement project.

We used Cochran-Armitage trend tests and interrupted time-series analysis to test for significance in the change in OMEs prescribed before vs after HB21.5 We also abstracted opioid refills as a potential counterbalance to a reduction in the initial dosage of opioids allowable under the new law. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and P values less than .05 were considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 1343 patients received an opioid prescription in the study period (pre-HB21: 649 patients; post-HB21: 694 patients). The median (interquartile range) age was 63 (54-71) years; 600 patients (44.6%) were male, and 1158 patients (86.2%) were white.

Overall, we found a significant decrease from period 1 compared with period 2 in the percentage of patients prescribed any opioids at discharge (609 of 649 [93.8%] vs 613 of 694 [88.3%]; P < .001), the dosages of OMEs at discharge (mean [SD], 497.2 [501.3] vs 208.4 [203.6]; P < .001; median [interquartile range], 300 [150-750] vs 135 [75-315]; P < .001), and the percentage of patients prescribed more than 200 OMEs (468 of 649 [72.1%] vs 306 of 694 [44.1%]; P < .001). We did not detect a difference in the refill rate between periods 1 and 2 (161 of 649 [24.8%] vs 158 of 694 [22.8%]; P = .40).

Of the 25 surgeries included in this study, 18 had a statistically significant decrease in the OMEs prescribed (range of mean decreases, 91-632 OMEs; range of median decreases, 90-690 OMEs). The largest decreases in opioid prescribing were in total knee arthroplasty (change, 990.7 to 397.6 mean OMEs [−40.1%]; P < .001), breast lumpectomy (change, 157.6 to 63.0 mean OMEs [−40.0%]; P < .001), cholecystectomy (change, 258.5 to 118.7 mean OMEs [−45.9%]; P < .001), and prostatectomy (change, 254.6 to 92.6 mean OMEs [−36.4%]; P < .001).

Among patients who were opioid naive, we again found a significant decrease from period 1 compared with period 2 in the percentage of patients prescribed any opioids at discharge (466 of 478 [97.5%] vs 495 of 535 [92.5%]; P < .001), the dosage of OMEs at discharge (mean [SD], 454.4 [370.8] vs 195.3 [183.6]; P < .001; median [interquartile range], 300 [150-750] vs 135 [90-315]; P < .001), and the percentage of patients prescribed more than 200 OMEs (344 of 478 [72.0%] vs 223 of 535 [41.7%]; P < .001). We did not detect a difference in the refill rate between periods 1 and 2 (103 of 478 [21.5%] vs 107 of 535 [20.0%]; P = .59).

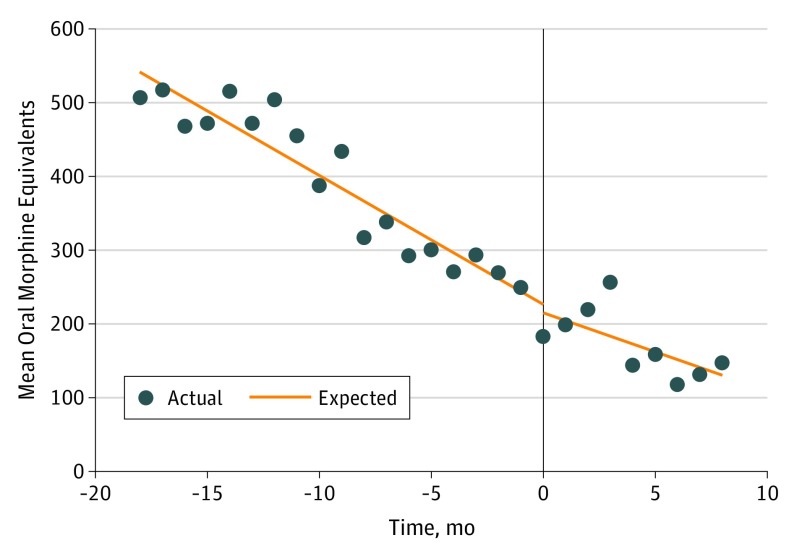

However, we did not detect a statistically significant difference in the interrupted time-series analysis of the decrease in mean OMEs prescribed before and after HB21. The period before implementation included January 2017 through June 2018, and the period after implementation was from July 2018 through March 2019. We used months as units of time to have enough data points to complete an interrupted time-series analysis. We did not find a difference in the slopes between the 2 periods (Figure).

Figure. Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Opioid Prescribing Practices at Discharge, Before and After Florida House Bill 21 Was Implemented.

Discussion

The opioid crisis is so severe that opioid use–associated deaths have overtaken car crash fatalities in number.6 Many state governments have taken matters into their own hands to try to stave off additional harm, and Florida is no exception. We sought to quantify the outcomes associated with HB21 on opioid prescribing for acute postoperative pain at our institution.

This study has limitations. This is a retrospective analysis of a single institution’s prescribing patterns over a 1-year period. Because of the large influence of opioids on the US health system and economy, there are many factors that could have affected prescribing patterns. Furthermore, there is likely to be a limit of how much postoperative opioid prescribing can decrease, thus constraining additional reductions in opioid prescriptions over time.

We found a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of patients prescribed any opioids at discharge, the amount of opioids prescribed at discharge, and the percentage of patients prescribed more than 200 OMEs between the 2 three-month periods studied. However, in the interrupted time-series analysis of mean OMEs prescribed, the rate of decrease in OMEs prescribed did not significantly change before and after HB21. Notably, we did not detect any difference in opioid refill rates.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Published 2018. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 2.Florida Senate Health and Human Services Committee and Health Quality Subcommittee CS/CS/HB 21: controlled substances. https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2018/21/. Published 2018. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 3.Thiels CA, Anderson SS, Ubl DS, et al. Wide variation and overprescription of opioids after elective surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;266(4):564-573. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Opioid oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion-Factors-vFeb-2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 5.Vu JV, Howard RA, Gunaseelan V, Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Englesbe MJ. Statewide implementation of postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):680-682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1905045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Safety Council Preventable deaths: odds of dying. https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/all-injuries/preventable-death-overview/odds-of-dying/data-details/. Published 2018. Accessed March 1, 2019.