Key Points

Question

What is the association of management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with the day of the week?

Findings

In this claims-based cohort study of 38 144 commercially insured US patients with incident rhegmatogenous retinal detachment between 2008 and 2016, rhegmatogenous retinal detachments repaired during the weekend were more likely to be repaired with pneumatic retinopexy, patients undergoing pneumatic retinopexy on Sundays were more likely to undergo reoperation, and patients who received a diagnosis on Fridays waited longer for repair.

Meaning

These results suggest variation in care patterns of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment by day of the week.

Abstract

Importance

Because variation in care on weekends has been reported in many surgical fields, it is of interest if variations were noted for care patterns of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments (RRDs).

Objective

To assess the association between modality of RRD repair and day of the week that patients receive a diagnosis or undergo RRD repair.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective claims-based cohort analysis was performed of primary RRD surgery for 38 144 commercially insured patients in the United States who received a diagnosis of incident RRD between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2016, and underwent repair within 14 days of diagnosis. Multinomial regression models were used to assess patients’ likelihood of repair with different modalities, logistic regression models were used to assess patients’ likelihood of reoperation, and linear regression models were used to assess time from diagnosis to repair. Data analysis was performed from March 9 to September 5, 2019.

Exposures

Day of the week that the patient received a diagnosis of RRD or underwent RRD repair.

Main Outcome and Measures

Modality of repair, time from diagnosis to repair, and 30-day reoperation rate.

Results

Among the 38 144 patients in the study (23 031 men [60.4%]; mean [SD] age at diagnosis, 56.8 [13.4] years), pneumatic retinopexy (PR) was more likely to occur when patients received a diagnosis of RRD on Friday (relative risk ratio [RRR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.17-1.60), Saturday (RRR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.36-2.20), or Sunday (RRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.08-2.17) compared with Wednesday. Pneumatic retinopexy was more likely to be used for surgical procedures on Friday (RRR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.33-1.80), Saturday (RRR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.61-2.56), Sunday (RRR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.55-3.35), or Monday (RRR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.46-1.98). Patients undergoing PR on Sundays were more likely to receive another procedure (PR, scleral buckle, or pars plana vitrectomy) within 30 days (odds ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.07-2.45). An association between the need for reoperation for repairs performed via scleral buckle or pars plana vitrectomy and the day of the week of the initial repair was not identified. Patients who received a diagnosis on a Friday waited a mean of 0.28 days (95% CI, 0.20-0.36 days) longer for repair than patients who received a diagnosis on a Wednesday.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that management of RRD varies according to the day of the week that diagnosis and repair occurs, with PR disproportionately likely to be used to repair RRDs during the weekend. Ophthalmologists should be aware that these results suggest that patients undergoing PR on Sundays may be more likely to require reoperation within 30 days.

This cohort study assesses the association between modality of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair and the day of the week that patients receive a diagnosis or undergo retinal detachment repair.

Introduction

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is one of the few ophthalmic conditions that requires urgent intervention to preserve vision, even in eyes in which the macula is already detached.1,2 There are several approaches to repair RRD, including barricade laser photocoagulation, pneumatic retinopexy (PR), scleral buckle placement (SB) with cryotherapy, and pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with or without SB. Pneumatic retinopexy has traditionally been used for RRDs with small breaks in the superior clock-hours of the retina, but over time, indications for PR have expanded to include more complicated detachments.3,4 Unlike SB and PPV, PR may be completed in the outpatient office setting.5,6

Pneumatic retinopexy is associated with lower rates of initial reattachment and higher rates of reoperation than SB or PPV, although the estimated rates of reattachment vary.3,7,8,9 Even accounting for this variation, PR is a significantly less expensive technique than SB or PPV to repair RRDs; cost-effectiveness analyses indicate its expanded use would be associated with substantial cost savings to the health care system.10,11,12 Despite the lower costs of PR and research supporting expanded indications for its use, the proportion of RRDs repaired by PR has decreased in recent years and the proportion of RRDs repaired by PPV has increased.13,14

The reasons for the relative decrease in the use of PR are likely multifactorial and may be associated with variables at the level of the patient, the physician, or the wider health care system. In an analysis of commercial insurance claims data, physician-level variation, independent of individual patient attributes, was associated with a substantial proportion of the variation in the types of surgery that patients received.15 One possible factor in a physician’s choice of RRD surgical approach may be the logistical challenges of performing SB or PPV repair, including the availability of equipment, open facilities, and trained staff. Depending on the institution, operating room time for weekends or after-hours ophthalmic surgical procedures may be more difficult to schedule, which may delay the timing of the repair. A recent study from a large private practice retina group found that patients with fovea-sparing RRDs were more likely to have their detachments repaired with PR if they received treatment on the weekend.16

In other fields of medicine, studies suggest that inpatient and outpatient management of patients varies according to the day of the week and time of day that patients present for care.17 Postoperative outcomes have been associated with the day of the week of surgery for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, hip arthroplasty, or liver transplant, and some studies have noted increased mortality among patients admitted to the hospital on weekends.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 Additional studies have concluded that these findings are spurious or are due to differences in patient characteristics that are associated with day of the week, but there is evidence, at least in certain acute conditions, that patterns of care are associated with temporal trends in patients’ presentation to care and that these patterns may be associated with patient outcomes.31,32,33,34,35

To our knowledge, there has not been a large multi-institution study investigating the presence of an association between the day of the week and diagnosis and treatment in ophthalmology. We used a large database of commercially insured patients with a new diagnosis of RRD to determine whether initial management of RRDs is associated with the day of the week that patients received the diagnosis or the day of the week that they underwent RRD repair. We focused on the variation in the use of PR by day of the week given that PR may be a favorable substitute for PPV and SB during days when access to operating rooms is more limited. We investigated whether the waiting time between receiving a diagnosis of RRD and undergoing surgery is associated with day of the week and whether reoperation rates vary according to the day that patients’ initial procedures were performed. These analyses illustrate how variables not associated with patient characteristics are associated with physician decision-making and patient care in a complex health care system.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using commercial insurance claims for primary RRD surgery for 38 144 commercially insured patients in the United States who received a diagnosis of incident RRD between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2016, to investigate the association between management of RRD and the day of the week that the patient received a diagnosis of RRD or underwent RRD repair. As a secondary analysis of deidentified administrative data, this study was exempt from Stanford University Institutional Review Board approval.

Data Source and Sample Selection

We selected our cohort from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database, which comprises more than 240 000 000 patients insured by 350 unique health carriers. MarketScan contains patient-level demographic information as well as diagnosis and procedural codes from both inpatient and outpatient encounters with health care professionals. This database has been used extensively in the health care literature and has been used in prior studies of RRD surgery.15,36

We included patients with an incident diagnosis of RRD who underwent repair with cryotherapy, laser photocoagulation, PR, SB, or PPV within 14 days of their first RRD diagnosis (eFigure in the Supplement). We restricted our sample to patients with continuous enrollment in the MarketScan database to avoid including patients who received care during the study period that was not recorded in the database. We further restricted our sample to patients with at least 365 days of enrollment preceding their first diagnosis of RRD to minimize the inclusion of patients with a preexisting RRD. We required at least 30 days of coverage after the repair of their RRD to allow us to calculate 30-day revision rates for these primary repair procedures.

All diagnoses were identified based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes, and all treatment procedures were identified based on Current Procedural Terminology codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement). In cases in which cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation occurred on the same day as PR, SB, or PPV, the procedure was coded as the more invasive procedure (PR, SB, or PPV). In cases in which SB and PPV codes occurred on the same date, the procedure was coded as PPV because Current Procedural Terminology codes for RRD repair include vitrectomy with or without scleral buckling (among other procedures).

We excluded patients with any diagnosis of tractional retinal detachment, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, sickle cell disease, retinoschisis, chorioretinitis, endophthalmitis, ruptured globe, retinal vascular occlusions, serous retinal detachments, or choroidal hemorrhage or rupture. Furthermore, we limited our sample to patients with a new diagnosis of RRD by excluding any patient with any RRD repair procedure that preceded their first diagnosis of RRD.

Statistical Analysis

We used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate the association between the types of procedure used to repair RRD and the day of the week. We estimated models that associated repair technique with the day of the week of RRD diagnosis, as well as models that associated repair technique with the day of the week of surgery. Our models were adjusted for patient age at diagnosis, patient sex (previous studies have noted an association between sex and repair procedure),13,15 year of surgery (previous studies have noted changes in repair type over time),13 type of health insurance plan, location of surgery (outpatient office, inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, emergency department, ambulatory surgical center, or other location), and the presence of ocular comorbidities that may be associated with the choice of repair technique (myopia, pseudophakia, lattice degeneration, and vitreous hemorrhage).13,15 Ocular comorbidities were coded using a 365-day lookback period (prior to the index RRD diagnosis) and a 30-day look-forward period (after index RRD diagnosis) to account for any comorbidities that may have been diagnosed only at the date of diagnosis or the date of surgery.

In addition to characterizing variation in repair of RRDs over days of the week, we also used adjusted logistic regression models to estimate the association between day of initial PR and need for subsequent surgical revision (defined as another Current Procedural Terminology code for PR, SB, or PPV occurring within 30 days of the initial PR repair). These models also adjusted for patient age at diagnosis, year of surgery, patient sex, year of surgery, type of health insurance plan, and location of surgery. Similarly, we estimated the association between time to repair (diagnosis date to repair date) and day of the week of diagnosis using linear regression models adjusted for the same covariates. We calculated 2-sided P values for day of the week variables with midweek (Wednesday) as the reference base category, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

A total of 265 616 patients underwent RRD repair, of whom 38 144 met study inclusion criteria between 2008 and 2016 (Figure 1). The mean (SD) patient age at index diagnosis was 56.8 (13.4) years (Table 1). A total of 23 031 patients (60.4%) were men. The most common ocular comorbidities in this sample were lattice degeneration (4387 [11.5%]) and vitreous hemorrhage (3043 [8.0%]). Most patients received a diagnosis of RRD on Monday (8337 [21.9%]), fewer received a diagnosis on Sunday (617 [1.6%]), and most underwent surgery on Thursday (8031 [21.1%]), with the fewest receiving surgery on Sunday (484 [1.3%]).

Figure 1. All Cryotherapy, Laser Photocoagulation, Pneumatic Retinopexy, Scleral Buckle, and Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV) Procedures Performed Among 37 933 Unique Patients With a New Diagnosis of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment (RRD).

Table 1. Demographics of Patients With a New Diagnosis of RRD, 2008-2016.

| No. (%) (N = 38 144) | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 56.8 (13.4) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 15 113 (39.6) |

| Ocular comorbidities | |

| Myopia | 694 (1.8) |

| Pseudophakia | 309 (0.8) |

| Lattice degeneration | 4387 (11.5) |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 3043 (8.0) |

| Primary repair of RRD | |

| Cryotherapy | 503 (1.3) |

| Laser photocoagulation | 6733 (17.7) |

| Pneumatic retinopexy | 5220 (13.7) |

| Scleral buckle | 3728 (9.8) |

| Pars plana vitrectomy | 21 749 (57.0) |

| Revision of pneumatic retinopexy within 30 d, No./total No. (%) | 1359/5220 (26.0) |

| Day of diagnosis | |

| Sunday | 617 (1.6) |

| Monday | 8337 (21.9) |

| Tuesday | 7603 (19.9) |

| Wednesday | 6807 (17.8) |

| Thursday | 6799 (17.8) |

| Friday | 6473 (17.0) |

| Saturday | 1508 (4.0) |

| Day of surgery | |

| Sunday | 484 (1.3) |

| Monday | 6101 (16.0) |

| Tuesday | 7758 (20.3) |

| Wednesday | 7305 (19.2) |

| Thursday | 8031 (21.1) |

| Friday | 6598 (17.3) |

| Saturday | 1656 (4.3) |

| Place of repair | |

| Outpatient office | 12 912 (33.9) |

| Inpatient hospital | 149 (0.4) |

| Outpatient hospital | 19 549 (51.3) |

| Emergency department | 122 (0.3) |

| Ambulatory surgery center | 5061 (13.3) |

| Other | 140 (0.4) |

| Type of health plan | |

| Comprehensive health plan | 3613 (9.5) |

| Exclusive provider organization | 620 (1.6) |

| Health maintenance organization | 3543 (9.3) |

| Point of service | 2442 (6.4) |

| Preferred provider organization | 23 031 (60.4) |

| Point of service with capitation | 217 (0.6) |

| Consumer-driven health plan | 2008 (5.3) |

| High deductible health plan | 1357 (3.6) |

Abbreviation: RDD, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

The most common type of repair was PPV (21 749 [57.0%]), followed by laser photocoagulation (6733 [17.7%]), PR (5220 [13.7%]), SB (3728 [9.8%]), and cryotherapy (503 [1.3%]) (Table 1). A total of 1359 patients (26.0%) whose primary repair was completed with PR underwent subsequent RRD repair within 30 days of their primary repair by either repeated PR, SB, or PPV.

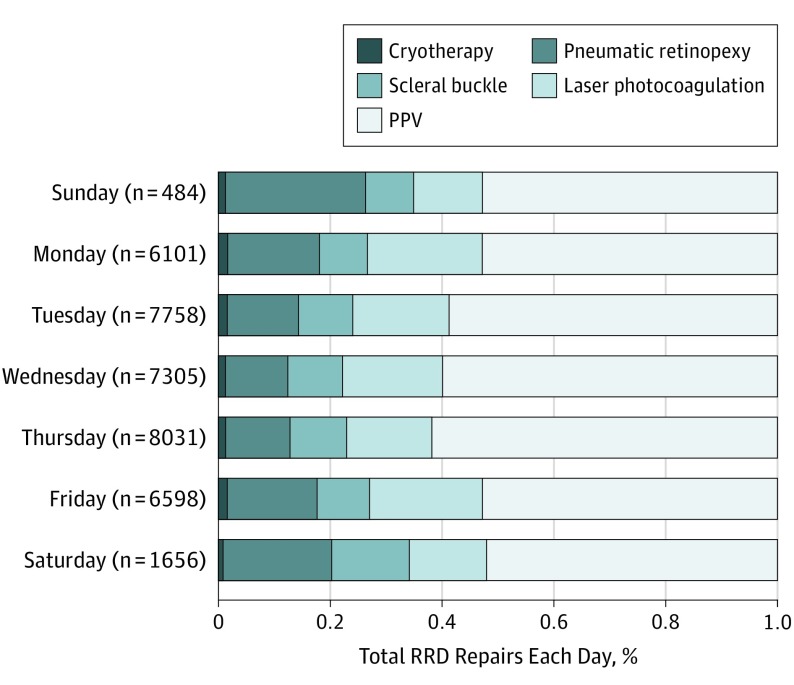

Variation in Primary Repair Technique by Day of Week

The relative proportion of all RRD repairs accounted for by each repair technique varies by the day of the week that the repair is performed, with the most dramatic changes apparent in the use of PR. Pneumatic retinopexy accounted for 25.0% of all repairs (121 of 484) performed on Sundays but only 11.2% of repairs (816 of 7305) on Wednesdays (P < .001). Other procedures exhibited variation in the share of surgical procedures they accounted for on different days, although less so than PR (the maximum and minimum shares of surgical procedures on different days of the week for other procedures were as follows: cryotherapy, from 80 of 8031 [1.0%] to 110 of 6598 [1.7%]; laser photocoagulation, from 60 of 484 [12.4%] to 1249 of 6101 [20.5%]; SB, from 41 of 484 [8.5%] to 227 of 1656 [13.7%]; and PPV, from 864 of 1656 [52.2%] to 4962 of 8031 [61.8%]) (Figure 1).

Differences in repair technique by day of the week were identified in adjusted multinomial logistic models that accounted for either the day of RRD diagnosis (eTable 2 in the Supplement) or the day of surgery (Table 2). Pneumatic retinopexy was most likely to occur when patients received a diagnosis of RRD on Friday (relative risk ratio [RRR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.17-1.60), Saturday (RRR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.36-2.20), or Sunday (RRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.08-2.17) compared with a base category of Wednesday. Pneumatic retinopexy was most likely to be the repair technique when the day of surgery was Friday (RRR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.33-1.80), Saturday (RRR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.61-2.56), Sunday (RRR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.55-3.35), or Monday (RRR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.46-1.98) compared with a base category of Wednesday. Other methods of repair exhibited less variation over days of the week, but cryotherapy and laser photocoagulation were both more likely to be used on Mondays (cryotherapy: RRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.02-1.94; laser photocoagulation: RRR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.51) and Fridays (cryotherapy: RRR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.11-2.05; laser photocoagulation: RRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.03-1.37) compared with Wednesdays, and SB was more likely to be used on Saturdays (RRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18-1.68). Independent of the day of the week, patients undergoing repair in later years of the study period were increasingly likely to receive PPV rather than cryotherapy, PR, or SB, a trend previously studied in a different administrative claims database.13

Table 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Model of Type of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair by Day of Surgery.

| Characteristic | Repair Procedure: Multinomial Logistic Regression (Reference Group: Pars Plana Vitrectomy) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryotherapy | Laser Photocoagulation | Pneumatic Retinopexy | Scleral Buckle | |||||

| RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Day of procedure (base: Wednesday) | ||||||||

| Sunday | 0.88 (0.34-2.30) | .80 | 0.65 (0.42-1.01) | .05 | 2.28 (1.55-3.35) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.60-1.24) | .43 |

| Monday | 1.41 (1.02-1.94) | .04 | 1.31 (1.13-1.51) | <.001 | 1.70 (1.46-1.98) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.90-1.16) | .75 |

| Tuesday | 1.36 (1.00-1.84) | .047 | 1.02 (0.89-1.17) | .78 | 1.22 (1.05-1.41) | .009 | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | .33 |

| Thursday | 0.86 (0.62-1.19) | .38 | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | .03 | 1.04 (0.89-1.20) | .64 | 1.02 (0.91-1.14) | .73 |

| Friday | 1.50 (1.11-2.05) | .009 | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | .02 | 1.55 (1.33-1.80) | <.001 | 1.08 (0.95-1.22) | .22 |

| Saturday | 0.80 (0.44-1.46) | .47 | 0.86 (0.68-1.10) | .23 | 2.03 (1.61-2.56) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.18-1.68) | <.001 |

| Year of surgery | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | .001 | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | .52 | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | .002 | 0.90 (0.88-0.91) | <.001 |

| Age at surgery, y | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .04 | 0.98 (0.98-0.98) | <.001 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .93 | 0.96 (0.95-0.96) | <.001 |

| Sex (base: male) | ||||||||

| Female | 1.37 (1.13-1.66) | .001 | 1.62 (1.48-1.77) | <.001 | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) | .51 | 1.18 (1.09-1.27) | <.001 |

| Ocular comorbidities | ||||||||

| Myopia | 0.64 (0.25-1.61) | .34 | 1.13 (0.82-1.56) | .45 | 1.31 (0.93-1.85) | .13 | 1.23 (0.96-1.57) | .10 |

| Pseudophakia | 0.40 (0.05-2.99) | .37 | 0.34 (0.17-0.68) | .002 | 1.15 (0.67-1.97) | .61 | 0.15 (0.05-0.46) | .001 |

| Lattice degeneration | 0.70 (0.50-0.98) | .04 | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) | .45 | 0.64 (0.55-0.75) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.15-1.42) | <.001 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 1.52 (1.14-2.02) | .004 | 1.15 (0.99-1.33) | .08 | 0.44 (0.36-0.53) | <.001 | 0.24 (0.19-0.31) | <.001 |

| Insurance plan (base: PPO) | ||||||||

| EPO | 1.00 (0.70-1.45) | .98 | 0.91 (0.77-1.08) | .29 | 0.95 (0.80-1.12) | .52 | 1.26 (1.08-1.46) | .003 |

| HMO | 1.06 (0.53-2.10) | .87 | 1.16 (0.84-1.61) | .36 | 0.94 (0.66-1.34) | .74 | 0.98 (0.73-1.31) | .88 |

| POS | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | .87 | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) | .81 | 1.14 (0.98-1.33) | .09 | 1.15 (1.02-1.30) | .02 |

| Comprehensive | 1.01 (0.68-1.50) | .95 | 1.23 (1.03-1.46) | .02 | 1.03 (0.85-1.24) | .79 | 0.96 (0.82-1.12) | .59 |

| POS with capitation | 0.92 (0.31-2.72) | .89 | 0.74 (0.43-1.27) | .27 | 0.87 (0.50-1.51) | .62 | 1.24 (0.78-1.96) | .37 |

| CDHP | 1.07 (0.69-1.65) | .76 | 1.00 (0.83-1.21) | .99 | 1.14 (0.93-1.40) | .19 | 1.26 (1.08-1.48) | .004 |

| HDHP | 1.16 (0.70-1.91) | .57 | 0.92 (0.73-1.16) | .47 | 1.31 (1.04-1.66) | .02 | 1.15 (0.95-1.39) | .15 |

| Place of surgery (base: office) | ||||||||

| Inpatient hospital | NA | NA | 0.01 (0.00-0.03) | <.001 | 0.02 (0.01-0.05) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.64-1.65) | .92 |

| Outpatient hospital | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | <.001 | 0.00 (0.00-0.01) | <.001 | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.69-0.90) | <.001 |

| Emergency department | 0.04 (0.01-0.27) | .001 | 0.03 (0.02-0.06) | <.001 | 0.02 (0.01-0.05) | <.001 | 1.32 (0.82-2.12) | .26 |

| Ambulatory surgical center | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | <.001 | 0.01 (0.01-0.02) | <.001 | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | <.001 | 0.54 (0.46-0.64) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.03 (0.00-0.21) | <.001 | 0.03 (0.02-0.05) | <.001 | 0.04 (0.02-0.07) | <.001 | 0.29 (0.13-0.63) | .002 |

Abbreviations: CDHP, consumer-driven health plan; EPO, exclusive provider organization; HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HMO, health maintenance organization; NA, not applicable; POS, point of service; PPO, preferred provider organization; RRR, relative risk ratio.

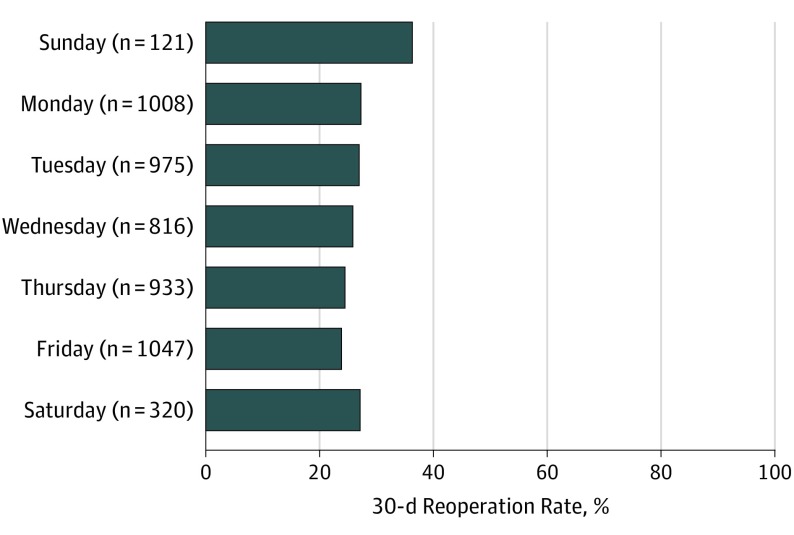

Need for Reoperation, by Primary Repair Day of Week

Models estimating 30-day reoperation by day of PR treatment find some variation in surgical success, with patients who undergo repair on Sundays more likely to have another PR, SB, or PPV within the next 30 days (odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% CI, 1.07-2.45). Patients receiving PR on other days, including Fridays (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.72-1.11) and Saturdays (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.79-1.45), are no more likely to receive a second repair within 30 days than patients undergoing repair on Wednesdays (Table 3, Figure 2). The need for reoperation for repairs done via SB or PPV is not associated with the day of the week of the initial repair (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Models Estimating 30-Day Revision of Initial Pneumatic Retinopexy, by Day of Week of the Index Procedurea.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Day of index pneumatic retinopexy (base: Wednesday) | ||

| Sunday | 1.62 (1.07-2.45) | .02 |

| Monday | 1.06 (0.86-1.32) | .57 |

| Tuesday | 1.03 (0.83-1.28) | .80 |

| Thursday | 0.92 (0.74-1.15) | .48 |

| Friday | 0.89 (0.72-1.11) | .29 |

| Saturday | 1.07 (0.79-1.45) | .65 |

| Year of surgery | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | .64 |

| Age at surgery, y | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | <.001 |

| Sex (base: male) | ||

| Female | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | <.001 |

| Ocular comorbidities | ||

| Myopia | 1.50 (0.96-2.36) | .08 |

| Pseudophakia | 1.92 (0.96-3.86) | .07 |

| Lattice degeneration | 1.24 (0.99-1.55) | .06 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 1.94 (1.49-2.53) | <.001 |

| Insurance plan (base: PPO) | ||

| EPO | 1.25 (0.98-1.60) | .07 |

| HMO | 0.67 (0.39-1.15) | .15 |

| POS | 0.96 (0.78-1.20) | .74 |

| Comprehensive | 0.94 (0.72-1.24) | .68 |

| POS with capitation | 1.22 (0.59-2.52) | .58 |

| CDHP | 0.82 (0.61-1.09) | .17 |

| HDHP | 0.87 (0.63-1.20) | .39 |

| Place of surgery | ||

| Inpatient hospital | 2.17 (0.56-8.33) | .26 |

| Outpatient hospital | 0.92 (0.71-1.18) | .51 |

| Emergency department | 0.44 (0.05-3.67) | .45 |

| Ambulatory surgical center | 0.95 (0.60-1.49) | .81 |

| Other | 0.54 (0.12-2.42) | .42 |

Abbreviations: CDHP, consumer-driven health plan; EPO, exclusive provider organization; HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HMO, health maintenance organization; POS, point of service; PPO, preferred provider organization; OR, odds ratio.

Defined as subsequent pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckle, or pars plana vitrectomy within 30 days of the index procedure.

Figure 2. Thirty-Day Revisions of Initial Pneumatic Retinopexy, by Day of Week of the Index Procedure .

Revisions defined as subsequent pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckle, or pars plana vitrectomy within 30 days of the index procedure. Total, 1359 revisions of 5220 pneumatic retinopexies.

Time From Diagnosis to Repair, by Diagnosis Day of Week

The day of the week that patients receive a diagnosis of RRD is associated with the time between diagnosis and repair in addition to being associated with the type of procedure they receive for repair. Patients are more likely to receive surgery more quickly when they receive a diagnosis of RRD on a Sunday. Patients who received a diagnosis on a Sunday received surgery a mean of 0.37 days (95% CI, 0.17-0.57) faster than patients who received a diagnosis on a Wednesday. Patients who received a diagnosis on a Friday waited a mean of 0.28 days (95% CI, 0.20-0.36) longer for repair than patients who received a diagnosis on a Wednesday. Patients who were treated in an outpatient office setting received repairs a mean of 0.89 days (95% CI, 0.51-1.28) faster than patients receiving treatment in hospitals and 1.33 days (95% CI, 1.26-1.41) faster than patients receiving treatment in ambulatory surgical centers. Increased mean wait times for patients who received a diagnosis on a Friday are associated with patients who receive PPV or SB; time from diagnosis to repair by PR is not associated with day of diagnosis (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We used a large cohort of commercially insured patients undergoing RRD repair to investigate the presence of an association between day of the week and receiving a diagnosis or undergoing treatment in ophthalmology and, specifically, in vitreoretinal surgery. We found evidence of temporal trends in the management of newly diagnosed RRDs, particularly regarding the use of PR. Vitreoretinal surgeons are more likely to use PR to repair RRDs when patients present just before or on the weekend. Our study is grounded in the premise that vitreoretinal surgeons always choose the most appropriate procedure for their given patient, but it is likely that their decisions may also be subject to scheduling obstacles that may delay surgical timing or affect convenience, including limited weekend access to operating room time or availability of experienced staff.

In our cohort of more than 38 000 patients, those who presented with a new RRD on a Friday waited a mean of 0.28 days longer to receive repair than patients who presented midweek on a Wednesday. Among patients who require urgent treatment on a weekend, surgeons may be substituting PR for their preferred method of primary repair because PR can be completed in the office or initiated in an emergency department setting. It is also possible that performing a longer surgical procedure on the weekend is time-consuming, and PR may be used as a staged or temporizing procedure. The placement of an expansile gas bubble may help to reattach the retina initially and, even if unsuccessful, may protect the macula, allowing for a planned surgical repair on a routine schedule.

Our results also support the notion that patients who receive a repair in the office have shorter surgical wait times than patients whose RRD is repaired in the operating room setting. Thus, patients presenting on a Friday who do not require an immediate repair may be more likely to have their surgery deferred until the following week, and patients who do require an immediate repair are more likely to receive PR, the only procedure that can be performed in the office.

This behavior may also explain the shorter mean wait times for surgery experienced by patients who present on Sundays, as well as the increased likelihood that these patients will undergo RRD repair with PR. Patients who present on the weekend may represent more urgent cases of RRD, on average, than patients who come to the clinic on weekdays, and they may require more urgent intervention. In the setting of constrained weekend operating room availability, surgeons may forego other primary repair methods in favor of PR. Substitution away from a preferred surgical method would be consistent with the finding that RRDs repaired via PR on Sundays are at higher risk for requiring revision within 30 days because surgeons may be using procedures they are less comfortable with in these cases, or they may be using PR to repair detachments that do not meet the indications these surgeons may otherwise use for PR. In a retrospective, multisurgeon study of RRD repair patterns, Lee et al16 also found lower rates of successful single-operation repairs for procedures conducted on the weekend, but they caution that the results are drawn from a very small proportion of patients undergoing repair on the weekends.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies in various fields in medicine that have noted variance in patterns of care associated with the day of the week, and they conclude that these patterns are associated with a complex interplay between different aspects of the health care system, including availability of physicians, equipment, and support staff on weekends and at different times of day.34,35 Our results are also consistent with the findings of a recent analysis by members of our group that variation in the management of newly diagnosed RRDs is associated with variation in individual physician management decisions.15 This physician-level variation likely encompasses both physicians’ personal preferences and practice heuristics, as well as the complex realities of the health care system that physicians must navigate to provide care to their patients.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. As with all studies of administrative claims data, our findings are limited by the lack of rich clinical information that would aid in parsing the patterns we observe. We could not identify the location or severity of RRD or the presence of risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy to evaluate indications for different RRD repair techniques, nor did we have access to other clinical data, such as visual acuity outcomes. Other unobserved patient-, clinician-, or facility-related factors may also be associated with decisions around the type and timing of surgical repair. Although we found evidence that PR is disproportionately likely to be used on weekends, our findings may still represent an underestimate of the share of RRDs repaired by PR on weekends because surgeons may neglect to bill for after-hours office-based procedures such as PR, and offices may be less likely to fully capture charges for these after-hours procedures.

Conclusions

Our findings are relevant to administrators and policy makers responsible for allocating constrained health care system resources, as well as to vitreoretinal fellowship programs responsible for training new surgeons in RRD management. Previous studies that have noted variance in patient mortality for acute conditions associated with day of hospital admission have prompted controversial conversations about restructuring work hours for physicians, as well as calls to clarify the causal pathway responsible for this “weekend effect.”30,34,37 Although our findings are more circumspect with less severe outcomes, we found higher reoperation rates after PR performed on the weekend. However, the differences in cost, indications, and outcomes between PR, SB, and PPV warrant a thorough investigation into the real-world use of each surgical approach.

eFigure. Sample Selection Strategy

eTable 1. Diagnostic (ICD) and Procedure (CPT) Codes

eTable 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Model of Type of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair by Day of Diagnosis (N=36,831)

eTable 3. Logistic Regression Models Estimating 30-Day Revision of Initial Scleral Buckle (Defined as Subsequent PR, SB, or PPV Within 30 Days of the Index Procedure), by Day of Week of the Index Procedure (N=3,590)

eTable 4. Logistic Regression Models Estimating 30-Day Revision of Initial Pars Plana Vitrectomy (Defined as Subsequent PR, SB, or PPV Within 30 Days of the Index Procedure), by Day of Week of the Index Procedure (N=21,120)

eTable 5. Days From Index Diagnosis of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment to Repair by Day of Diagnosis (N=36,831)

References

- 1.Greven MA, Leng T, Silva RA, et al. . Reductions in final visual acuity occur even within the first 3 days after a macula-off retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(10):1503-1506. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bussel EM, van der Valk R, Bijlsma WR, La Heij EC. Impact of duration of macula-off retinal detachment on visual outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature. Retina. 2014;34(10):1917-1925. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandelcorn ED, Mandelcorn MS, Manusow JS. Update on pneumatic retinopexy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(3):194-199. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang TS, Pelzek CD, Nguyen RL, Purohit SS, Scott GR, Hay D. Inverted pneumatic retinopexy: a method of treating retinal detachments associated with inferior retinal breaks. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(3):589-594. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01896-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilton GF, Das T, Majji AB, Jalali S. Pneumatic retinopexy: principles and practice. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1996;44(3):131-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan CK, Lin SG, Nuthi AS, Salib DM. Pneumatic retinopexy for the repair of retinal detachments: a comprehensive review (1986-2007). Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(5):443-478. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatef E, Sena DF, Fallano KA, Crews J, Do DV. Pneumatic retinopexy versus scleral buckle for repairing simple rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD008350. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008350.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emami-Naeini P, Vuong VS, Tran S, et al. . Outcomes of pneumatic retinopexy performed by vitreoretinal fellows. Retina. 2019;39(1):186-192. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day S, Grossman DS, Mruthyunjaya P, Sloan FA, Lee PP. One-year outcomes after retinal detachment surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(3):338-345. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung JJ, Cheng J, Pan JY, Brinton DA, Hoang QV. Anatomic, visual, and financial outcomes for traditional and nontraditional primary pneumatic retinopexy for retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:187-200. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman DR, Shah CP, Heier JS. Expanded criteria for pneumatic retinopexy and potential cost savings. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):318-326. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang JS, Smiddy WE. Cost-effectiveness of retinal detachment repair. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):946-951. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves MG, Pershing S, Afshar AR. Choice of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair method in US commercially insured and Medicare Advantage patients, 2003-2016. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;196:82-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin MD, Hwang JC. Trends in vitreoretinal procedures for Medicare beneficiaries, 2000 to 2014. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(5):667-673. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vail D, Pershing S, Reeves MG, Afshar AR. The relative impact of patient, physician, and geographic factors on variation in primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment management [published online April 12, 2019]. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee IT, Lampen SIR, Wong TP, Major JC Jr, Wykoff CC. Fovea-sparing rhegmatogenous retinal detachments: impact of clinical factors including time to surgery on visual and anatomic outcomes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(5):883-889. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-04236-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiang EY, Mehta SJ, Small DS, et al. . Association of primary care clinic appointment time with clinician ordering and patient completion of breast and colorectal cancer screening. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193403. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng TW, Farber A, Kalish JA, et al. ; Vascular Quality Initiative . Carotid endarterectomy performed before the weekend is associated with increased length of stay. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;48:119-126. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathi P, Coleman S, Durbin-Johnson B, Giordani M, Pereira G, Di Cesare PE. Effect of day of the week of primary total hip arthroplasty on length of stay at a university-based teaching medical center. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2014;43(12):E299-E303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijland LMG, Karres J, Simons AE, Ultee JM, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Vrouenraets BC. The weekend effect for hip fracture surgery. Injury. 2017;48(7):1536-1541. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pauls LA, Johnson-Paben R, McGready J, Murphy JD, Pronovost PJ, Wu CL. The weekend effect in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):760-766. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briggs W, Guevel B, McCaskie AW, McDonnell SM. Multi- and univariate analyses of the weekend effect for elective lower-limb joint replacements. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100(1):42-46. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2017.0116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker F, Vogel T, Voß T, et al. . The weekend effect in liver transplantation. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giannoudis V, Panteli M, Giannoudis PV. Management of polytrauma patients in the UK: is there a “weekend effect”? Injury. 2016;47(11):2385-2390. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McVay DP, Walker AS, Nelson DW, Porta CR, Causey MW, Brown TA. The weekend effect: does time of admission impact management and outcomes of small bowel obstruction? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014;2(3):221-225. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A, Agarwal R, Ananthakrishnan AN. “Weekend effect” in patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(1):13-21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glance LG, Osler T, Li Y, et al. . Outcomes are worse in US patients undergoing surgery on weekends compared with weekdays. Med Care. 2016;54(6):608-615. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoehn RS, Go DE, Dhar VK, et al. . Understanding the “weekend effect” for emergency general surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(2):321-328. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3592-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shih YN, Chen YT, Shih CJ, et al. . Association of weekend effect with early mortality in severe sepsis patients over time. J Infect. 2017;74(4):345-351. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheikh HQ, Aqil A, Hossain FS, Kapoor H. There is no weekend effect in hip fracture surgery—a comprehensive analysis of outcomes. Surgeon. 2018;16(5):259-264. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barer D. Do studies of the weekend effect really allow for differences in illness severity? an analysis of 14 years of stroke admissions. Age Ageing. 2017;46(1):138-142. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedeli U, Gallerani M, Manfredini R. Factors contributing to the weekend effect. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1582. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bray BD, Steventon A. What have we learnt after 15 years of research into the “weekend effect”? BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(8):607-610. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, et al. ; SSNAP collaboration . Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):170-177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaziri K, Schwartz SG, Kishor KS, et al. . Rates of reoperation and retinal detachment after macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):26-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilford RJ, Chen YF. The ubiquitous weekend effect: moving past proving it exists to clarifying what causes it. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(8):480-482. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Sample Selection Strategy

eTable 1. Diagnostic (ICD) and Procedure (CPT) Codes

eTable 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Model of Type of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair by Day of Diagnosis (N=36,831)

eTable 3. Logistic Regression Models Estimating 30-Day Revision of Initial Scleral Buckle (Defined as Subsequent PR, SB, or PPV Within 30 Days of the Index Procedure), by Day of Week of the Index Procedure (N=3,590)

eTable 4. Logistic Regression Models Estimating 30-Day Revision of Initial Pars Plana Vitrectomy (Defined as Subsequent PR, SB, or PPV Within 30 Days of the Index Procedure), by Day of Week of the Index Procedure (N=21,120)

eTable 5. Days From Index Diagnosis of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment to Repair by Day of Diagnosis (N=36,831)