Key Points

Question

What are the comparative harms of contemporary treatments for localized prostate cancer through 5 years?

Findings

In this prospective, population-based study of 1386 men with favorable-risk prostate cancer and 619 men with unfavorable-risk prostate cancer, most functional differences, measured with Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite scores, associated with treatments (favorable-risk disease: active surveillance, nerve-sparing prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or low-dose-rate brachytherapy; unfavorable-risk disease: prostatectomy or external beam radiation therapy with androgen deprivation therapy) attenuated over time with no clinically meaningful bowel or hormonal functional differences at 5 years. However, prostatectomy was associated with worse incontinence over 5 years (adjusted mean difference of –10.9 for favorable-risk disease and −23.2 for unfavorable-risk disease) and worse sexual function at 5 years for unfavorable-risk disease (adjusted mean difference, −12.5).

Meaning

These estimates of the long-term bowel, bladder and sexual function after localized prostate cancer treatment may clarify expectations and enable men to make informed choices about care.

Abstract

Importance

Understanding adverse effects of contemporary treatment approaches for men with favorable-risk and unfavorable-risk localized prostate cancer could inform treatment selection.

Objective

To compare functional outcomes associated with prostate cancer treatments over 5 years after treatment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective, population-based cohort study of 1386 men with favorable-risk (clinical stage cT1 to cT2bN0M0, prostate-specific antigen [PSA] ≤20 ng/mL, and Grade Group 1-2) prostate cancer and 619 men with unfavorable-risk (clinical stage cT2cN0M0, PSA of 20-50 ng/mL, or Grade Group 3-5) prostate cancer diagnosed in 2011 through 2012, accrued from 5 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program sites and a US prostate cancer registry, with surveys through September 2017.

Exposures

Treatment with active surveillance (n = 363), nerve-sparing prostatectomy (n = 675), external beam radiation therapy (EBRT; n = 261), or low-dose-rate brachytherapy (n = 87) for men with favorable-risk disease and treatment with prostatectomy (n = 402) or EBRT with androgen deprivation therapy (n = 217) for men with unfavorable-risk disease.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient-reported function, based on the 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite (range, 0-100), 5 years after treatment. Regression models were adjusted for baseline function and patient and tumor characteristics. Minimum clinically important difference was 10 to 12 for sexual function, 6 to 9 for urinary incontinence, 5 to 7 for urinary irritative symptoms, and 4 to 6 for bowel and hormonal function.

Results

A total of 2005 men met inclusion criteria and completed the baseline and at least 1 postbaseline survey (median [interquartile range] age, 64 [59-70] years; 1529 of 1993 participants [77%] were non-Hispanic white). For men with favorable-risk prostate cancer, nerve-sparing prostatectomy was associated with worse urinary incontinence at 5 years (adjusted mean difference, −10.9 [95% CI, −14.2 to −7.6]) and sexual function at 3 years (adjusted mean difference, −15.2 [95% CI, −18.8 to −11.5]) compared with active surveillance. Low-dose-rate brachytherapy was associated with worse urinary irritative (adjusted mean difference, −7.0 [95% CI, −10.1 to −3.9]), sexual (adjusted mean difference, −10.1 [95% CI, −14.6 to −5.7]), and bowel (adjusted mean difference, −5.0 [95% CI, −7.6 to −2.4]) function at 1 year compared with active surveillance. EBRT was associated with urinary, sexual, and bowel function changes not clinically different from active surveillance at any time point through 5 years. For men with unfavorable-risk disease, EBRT with ADT was associated with lower hormonal function at 6 months (adjusted mean difference, −5.3 [95% CI, −8.2 to −2.4]) and bowel function at 1 year (adjusted mean difference, −4.1 [95% CI, −6.3 to −1.9]), but better sexual function at 5 years (adjusted mean difference, 12.5 [95% CI, 6.2-18.7]) and incontinence at each time point through 5 years (adjusted mean difference, 23.2 [95% CI, 17.7-28.7]), than prostatectomy.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort of men with localized prostate cancer, most functional differences associated with contemporary management options attenuated by 5 years. However, men undergoing prostatectomy reported clinically meaningful worse incontinence through 5 years compared with all other options, and men undergoing prostatectomy for unfavorable-risk disease reported worse sexual function at 5 years compared with men who underwent EBRT with ADT.

This cohort study compares functional outcomes, including sexual and bowel function and urinary incontinence, associated with active surveillance, surgery, or radiation therapy 5 years after treatment.

Introduction

The optimal management for localized prostate cancer depends on patient comorbidities, life expectancy, and cancer characteristics, and treatment choices need to be informed by reliable information about both cancer recurrence rates and adverse effects of alternative treatment options, particularly in the domains of urinary, bowel, and sexual function.1,2 Comparative data have had limitations because they compare older treatment techniques instead of robotic prostatectomy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy, do not report disease-risk–specific treatment outcomes, examine homogeneous populations, do not have an active surveillance comparative group, and/or have limited follow-up.3,4,5,6,7,8 The prospective population-based Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation study (CEASAR) was designed to inform men of the comparative harms of contemporary prostate cancer treatment alternatives.

Men with favorable-risk prostate cancer (clinical stage cT1 or cT21bN0M0, prostate-specific antigen [PSA] ≤20 ng/mL, and Grade Group 1-2) may be adequately treated with active surveillance, brachytherapy, nerve-sparing prostatectomy, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) alone.1,2 Men with unfavorable-risk prostate cancer (stage cT2cN0M0, PSA of 20-50 ng/mL, or Grade Group 3-5) require more intensive treatment; specifically, they require more extensive surgical resection with sacrifice of 1 or both nerves essential for erectile function in men undergoing prostatectomy and a more extensive radiation treatment area and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in men undergoing EBRT.1,2 This study analyzed patient-reported functional outcomes through 5 years after initiation of treatment. In contrast to the analysis of 3-year outcomes,9 the outcomes are reported by disease-risk group because treatment intensity and options vary by cancer severity.

Methods

This study recruited men with clinically localized prostate cancer from 5 population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program registries and the observational Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor prostate cancer registry from 2011 to 2012, as previously described.10,11,12 Institutional review board approval was obtained from each site and from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Participants provided written informed consent.

Surveys were completed at baseline and 6 months and 1, 3, and 5 years after enrollment (the last survey was completed in September 2017). Tumor characteristics, initial treatment, and treatment dates were determined from medical chart abstraction 1 year after enrollment.9,10 Treatment after 1 year was determined by patient report. Radiation and surgical treatment details were previously reported.10,13,14 Survival was determined from data linkage to Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program and Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor registries, with survival data through at least December 2017 for all registries.

Participants

Participants were categorized as having favorable-risk or unfavorable-risk disease for the analysis. Men with stage cT12bN0M0 or cT12bN0M0 prostate cancer, PSA less than or equal to 20 ng/mL, and in Grade Group 1 or 2 were categorized as having favorable-risk disease and received nerve-sparing prostatectomy, EBRT without ADT, low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy, and active surveillance.1 Men with stage cT2cN0M0 prostate cancer; PSA of 20 to 50 ng/mL; or in Grade Group 3, 4, or 5 were categorized as having unfavorable-risk disease and underwent either prostatectomy or EBRT with ADT.

Outcomes

The validated 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC) was used to evaluate patient-reported disease-specific function.15 Functional domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. Differences were interpreted as clinically meaningful if they were greater than the following previously published validated minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) for each EPIC domain: sexual function, 10-12; urinary incontinence, 6-9; urinary irritative, 5-7; bowel function, 4-6; and hormonal function, 4-6.16 The sexual function domain evaluated erection frequency and quality; the urinary incontinence domain, the extent of urinary leakage; the urinary irritative domain, urgency, dysuria, and urinary frequency; the bowel function domain, bowel urgency, bleeding, frequency, and pain; and the hormonal domain, symptoms such as low energy, gynecomastia, hot flashes, and weight gain.

The validated Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) was used to evaluate general health-related quality of life domains, including physical functioning, emotional well-being, and energy and fatigue.17,18 Domain scores range from 0-100, with 100 indicating the best function. Differences were interpreted as clinically meaningful if they were greater than the following previously published validated MCIDs for men with localized prostate cancer: physical functioning, 7; emotional well-being, 6; and energy and fatigue, 9.19

Covariates

Surveys captured patient-reported age, race/ethnicity (fixed categories), education, marital status, income, and insurance. Race/ethnicity (97.0% collected via self-report, 2.4% via cancer registry, and 0.5% unknown), was included because disease characteristics, treatment selection, and treatment morbidity may vary by race/ethnicity.20,21 Previously described validated instruments assessed patient-reported social support, depression, and decision-making style.15 The total illness burden index for prostate cancer measured comorbidity (with higher scores indicating more severe comorbidity burden).22

Statistical Analysis

Participants’ clinical and sociodemographic characteristics were summarized by risk groups and cancer treatment. Differences between treatment groups were assessed with Wilcoxon rank sum tests (continuous variables) or χ2 tests (categorical variables).

The primary outcomes were the EPIC-26 sexual, urinary incontinence, urinary irritative, bowel, and hormone domain scores and the SF-36 physical functioning, emotional well-being, and energy and fatigue domain scores. The secondary outcomes included the following a priori selected individual items used in calculating EPIC domain scores: sexual function bother, erection insufficient for penetration, urinary function bother, urinary leakage, burning on urination, frequent urination, bowel function bother, bloody stools, and bowel urgency. Because men with favorable-risk and unfavorable-risk disease had distinct characteristics and different treatment choices, the association between treatment and functional outcomes were evaluated separately for the 2 risk groups. Multivariable longitudinal linear regression was used for the primary outcomes and logistic regression models were used for the secondary outcomes. To account for the potential correlation among multiple records collected from the same individual at different times, generalized estimating equations were used with the Huber-White method to estimate robust covariance matrix.23,24 The following potential confounders were included in all models: age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, or other), total illness burden index for prostate cancer comorbidity score (0-2, 3-4, ≥5), cancer characteristics (for the favorable-risk cohort: PSA <10 ng/mL, Grade Group 1 and clinical stage ≤cT2a vs not; for the unfavorable-risk cohort: PSA >20 ng/mL or Grade Group 4-5 vs not), baseline physical functioning (continuous),17 social support scores (continuous),25 depression scores (continuous),26 participatory decision-making scale (continuous),27 time since treatment (continuous), enrollment site, and corresponding baseline EPIC domain scores (continuous). In all models, restricted cubic splines were used to allow nonlinear associations with the outcomes for age, time since treatment, and baseline domain scores. The goal was to compare functional outcomes among treatment groups. To simplify presentation in the favorable-risk participants, active surveillance was selected as the primary referent group; other comparisons are shown in the Supplement. For the unfavorable-risk cohort, prostatectomy was compared with EBRT with ADT. For domain scores and individual items, adjusted mean score differences or odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were reported, respectively. Missing values of regression model covariates, including the values of the baseline EPIC domain score or individual EPIC item, were imputed using the MICE (multiple imputation using chained equations) multiple imputation procedure.28,29 No outcome variables were imputed. In this procedure, missing values of covariates are imputed by modeling each covariate as an outcome in a regression model, using all other model covariates as predictors. In this case, only baseline data (excluding treatment) were used (see eMethods in the Supplement for additional details). In exploratory analyses, interactions were tested in each domain model between treatment and baseline function, comorbidity, race/ethnicity, and risk group. Prostate cancer–specific survival was compared using a log-rank test. Participants were censored at date of last registry follow-up. The proportional hazard assumption was checked by testing independence between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and time.30

Two-sided P values less than or equal to .05 were considered statistically significant. Because of the potential inflation of type I error rate due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. In addition, results were interpreted as clinically meaningful only if they met the MCID and statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.

Results

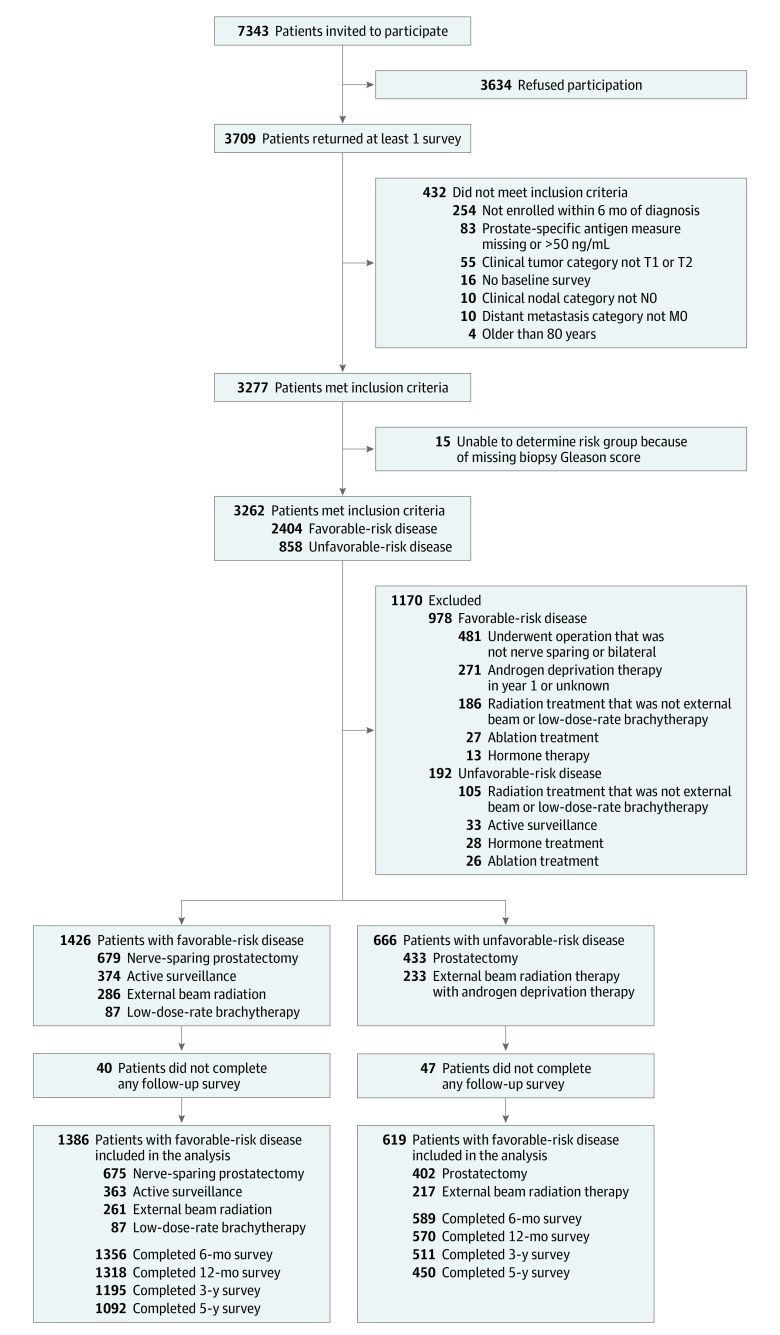

A total of 2005 men met inclusion criteria and completed the baseline and at least 1 postbaseline survey (median [interquartile range] age, 64 [59-70] years; 1529 of 1993 participants [77%] with race/ethnicity information were non-Hispanic white; Figure 1). Response rate was 97% at 6 months, 94% at 1 year, 85% at 3 years, and 77% at 5 years (details in eTable 1 in the Supplement). The frequency of missing covariates is quantified in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Flow of Participants in the Comparative Effectiveness Analyses of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) Study of the Association Between Contemporary Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years.

Median (interquartile range) follow-up for vital status was 73 (63-79) months. There was no statistically significant difference in prostate cancer survival over 5 years, with only 1 prostate cancer–related death in the favorable-risk group and 8 in the unfavorable-risk group (eTable 3 in the Supplement). There was no evidence of violation of the proportional hazard assumption (P = .92 for the favorable-risk group and P = .35 for the unfavorable-risk group).

Favorable-Risk Disease

Of 1386 men with favorable-risk disease, 675 (49%) underwent nerve-sparing prostatectomy, 363 (26%) underwent active surveillance, 261 (19%) underwent EBRT without ADT, and 87 (6%) underwent LDR brachytherapy (see eTable 4 in the Supplement for information on treatment details). Men treated with EBRT and active surveillance were older and had more comorbidities (Table). At 5 years, 89 of 363 participants (25%) who were initially undergoing active surveillance progressed to definitive treatment (44 [48%] underwent EBRT; 37 [43%], prostatectomy; 5 [6%], ADT; and 3 [3%], ablation).

Table. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics in a Study of the Association Between Contemporary Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years.

| Favorable-Risk Disease Groupa | Unfavorable-Risk Disease Groupa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve-sparing Prostatectomy (n = 675) | EBRT (n = 261) | LDR Brachy-Therapy (n = 87) | Active Surveillance (n = 363) | Combined (n = 1386) | P Value b | EBRT With ADT (n = 217) | Prostatectomy (n = 402) | Combined (n = 619) | P Valueb | |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 60 (56-65) | 68 (63-72) | 65 (61-70) | 67 (61-72) | 64 (58-69) | <.001 | 71 (66-74) | 64 (59-68) | 66 (61-71) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | (n = 672) | (n = 261) | (n = 86) | (n = 362) | (n = 1381) | 216 | 396 | 612 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 531 (79) | 198 (76) | 72 (84) | 291 (80) | 1092 (79) | .04 | 144 (67) | 293 (74) | 437 (71) | .08 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 60 (9) | 41 (16) | 9 (10) | 38 (10) | 148 (11) | 43 (20) | 49 (12) | 92 (15) | ||

| Hispanic | 54 (8) | 11 (4) | 2 (2) | 21 (6) | 88 (6) | 17 (8) | 32 (8) | 49 (8) | ||

| Asian | 19 (3) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | 33 (2) | 10 (5) | 13 (3) | 23 (4) | ||

| Other | 8 (1) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (1) | 20 (1) | 2 (1) | 9 (2) | 11 (2) | ||

| Education, No. (%) | (n = 662) | (n = 252) | (n = 85) | (n = 354) | (n = 1353) | (n = 206) | (n = 380) | (n = 586) | ||

| <High school | 44 (7) | 29 (12) | 5 (6) | 25 (7) | 103 (8) | .15 | 40 (19) | 41 (11) | 81 (14) | .01 |

| High school graduate | 131 (20) | 49 (19) | 20 (24) | 67 (19) | 267 (20) | 40 (19) | 84 (22) | 124 (21) | ||

| Some college | 150 (23) | 60 (24) | 28 (33) | 73 (21) | 311 (23) | 50 (24) | 73 (19) | 123 (21) | ||

| College graduate | 161 (24) | 52 (21) | 13 (15) | 86 (24) | 312 (23) | 38 (18) | 94 (25) | 132 (23) | ||

| Graduate or professional school | 176 (27) | 62 (25) | 19 (22) | 103 (29) | 360 (27) | 38 (18) | 88 (23) | 126 (22) | ||

| Marital status, No. (%) | (n = 662) | (n = 252) | (n = 84) | (n = 352) | (n = 1350) | (n = 206) | (n = 378) | (n = 584) | ||

| Married | 554 (84) | 183 (73) | 65 (77) | 289 (82) | 1091 (81) | .001 | 155 (75) | 313 (83) | 468 (80) | .03 |

| Comorbidity score,c No. (%) | (n = 665) | (n = 252) | (n = 85) | (n = 354) | (n = 1356) | (n = 208) | (n = 381) | (n = 589) | ||

| 0-2 | 240 (36) | 47 (19) | 27 (32) | 93 (26) | 407 (30) | <.001 | 33 (16) | 110 (29) | 143 (24) | <.001 |

| 3-4 | 294 (44) | 118 (47) | 26 (31) | 141 (40) | 579 (43) | 73 (35) | 163 (43) | 236 (40) | ||

| ≥5 | 131 (20) | 87 (35) | 32 (38) | 120 (34) | 370 (27) | 102 (49) | 108 (28) | 210 (36) | ||

| Prostate cancer risk category, No. (%) | 675 | 261 | 87 | 363 | 1386 | 217 | 402 | 619 | ||

| Low risk | 398 (59) | 153 (59) | 66 (76) | 301 (83) | 918 (66) | <.001 | .31 | |||

| Favorable intermediate risk | 277 (41) | 108 (41) | 21 (24) | 62 (17) | 468 (34) | |||||

| Unfavorable intermediate risk | 71 (33) | 148 (37) | 219 (35) | |||||||

| High risk | 146 (67) | 254 (63) | 400 (65) | |||||||

| PSA at diagnosis, median (IQR), ng/mL | 5 (4-6) [n = 675] | 6 (4-7) [n = 261] | 6 (4-7) [n = 87] | 5 (4-7) [n = 363] | 5 (4-7) [n = 1386] | .007 | 7 (5-13) [n = 217] | 6 (5-9) [n = 402] | 6 (5-10) [n = 619] | <.001 |

| Clinical tumor stage T1, No. (%) | 576 (85) [n = 674] | 217 (83) [n = 261] | 73 (84) [n = 87] | 304 (85) [n = 358] | 1170 (85) [n = 1380] | .84 | 124 (57) [n = 216] | 212 (53) [n = 401] | 336 (54) [n = 617] | .28 |

| Biopsy Grade Group, No. (%)d | 675 | 261 | 87 | 363 | 1386 | 217 | 401 | 618 | ||

| 1 | 437 (65) | 162 (62) | 71 (82) | 330 (91) | 1000 (72) | <.001 | 11 (5) | 41 (10) | 52 (8) | .07 |

| 2 | 238 (35) | 99 (38) | 16 (18) | 33 (9) | 386 (28) | 23 (11) | 41 (10) | 64 (10) | ||

| 3 | 85 (39) | 170 (42) | 255 (41) | |||||||

| 4-5 | 98 (45) | 149 (37) | 247 (40) | |||||||

| Accrual site | 675 | 261 | 87 | 363 | 1386 | 217 | 402 | 619 | ||

| Utah | 31 (5) | 5 (2) | 12 (14) | 52 (14) | 100 (7) | <.001 | 8 (4) | 33 (8) | 41 (7) | <.001 |

| Atlanta | 50 (7) | 27 (10) | 20 (23) | 44 (12) | 141 (10) | 19 (9) | 64 (16) | 83 (13) | ||

| Los Angeles | 221 (33) | 59 (23) | 16 (18) | 112 (31) | 408 (29) | 45 (21) | 112 (28) | 157 (25) | ||

| Louisiana | 169 (25) | 68 (26) | 29 (33) | 95 (26) | 361 (26) | 105 (48) | 103 (26) | 208 (34) | ||

| New Jersey | 142 (21) | 94 (36) | 7 (8) | 29 (8) | 272 (20) | 27 (12) | 46 (11) | 73 (12) | ||

| CaPSURE | 62 (9) | 8 (3) | 3 (3) | 31 (9) | 104 (8) | 13 (6) | 44 (11) | 57 (9) | ||

| Baseline EPIC score, median (IQR)e | ||||||||||

| Sexual function | 80 (53-100) [n = 648] | 60 (28-85) [n = 248] | 75 (38-85) [n = 85] | 75 (42-88) [n = 341] | 75 (42-90) [n = 1322] | <.001 | 48 (12-80) [n = 199] | 70 (33-85) [n = 381] | 61 (23-85) [n = 580] | <.001 |

| Urinary incontinence function | 100 (81-100) [n = 658] | 100 (79-100) [n = 251] | 100 (92-100) [n = 84] | 100 (85-100) [n = 346] | 100 (85-100) [n = 1339] | .29 | 100 (75-100) [n = 211] | 100 (79-100) [n = 386] | 100 (79-100) [n = 597] | .63 |

| Urinary irritative function | 88 (75-100) [n = 649] | 88 (75-94) [n = 250] | 94 (80-100) [n = 84] | 88 (75-100) [n = 384] | 88 (75-100) [n = 1331] | .26 | 88 (75-94) [n = 210] | 88 (69-100) [n = 385] | 88 (75-94) [n = 595] | .75 |

| Bowel function | 100 (96-100) [n = 662] | 100 (96-100) [n = 256] | 100 (96-100) [n = 86] | 100 (96-100) [n = 351] | 100 (96-100) [n = 1355] | .05 | 100 (92-100) [n = 212] | 100 (88-100) [n = 394] | 100 (88-100) [n = 606] | .62 |

| Hormonal function | 95 (90-100) [n = 651] | 95 (85-100) [n = 246] | 100 (81-100) [n = 84] | 95 (85-100) [n = 350] | 95 (85-100) [n = 1331] | .54 | 90 (80-95) [n = 203] | 90 (80-100) [n = 389] | 90 (80-100) [n = 592] | .02 |

| SF-36 score, median (IQR)f | ||||||||||

| General health scale | 80 (60-100) [n = 672] | 80 (60-80) [n = 259] | 80 (60-80) [n = 87] | 80 (60-80) [n = 363] | 80 (60-80) [n = 1381] | <.001 | 60 (60-80) [n = 216] | 80 (60-80) [n = 402] | 80 (60-80) [n = 618] | <.001 |

| Physical function scale | 100 (90-100) [n = 658] | 90 (75-100) [n = 254] | 95 (80-100) [n = 83] | 95 (80-100) [n = 343] | 95 (85-100) [n = 1338] | <.001 | 85 (55-100) [n = 207] | 95 (80-100) [n = 394] | 93 (70-100) [n = 601] | <.001 |

| Emotional well-being | 84 (68-92) [n = 662] | 84 (72-92) [n = 256] | 84 (76-95) [n = 85] | 88 (72-92) [n = 350] | 84 (72-92) [n = 1353] | .26 | 84 (68-92) [n = 213] | 84 (64-92) [n = 397] | 84 (64-92) [n = 610] | .10 |

| Energy/fatigue | 80 (65-89) [n = 662] | 74 (55-85) [n = 256] | 75 (55-85) [n = 86] | 75 (60-85) [n = 351] | 75 (60-85) [n = 1355] | .01 | 75 (55-85) [n = 213] | 75 (60-85) [n = 398] | 75 (55-85) [n = 611] | .13 |

| Social support scaleg | 95 (75-100) [n = 673] | 95 (70-100) [n = 260] | 95 (66-100) [n = 86] | 95 (75-100) [n = 361] | 95 (75-100) [n = 1380] | .19 | 90 (60-100) [n = 212] | 95 (75-100) [n = 399] | 95 (70-100) [n = 611] | .10 |

| Depression scaleh | 15 (4-30) [n = 659] | 11 (4-30) [n = 256] | 15 (4-33) [n = 85] | 11 (4-22) [n = 351] | 11 (4-30) [n = 1351] | .35 | 19 (7-33) [n = 210] | 19 (4-33) [n = 399] | 19 (5-33) [n = 609] | .79 |

| Participatory decision-makingi | 86 (71-93) [n = 673] | 79 (64-89) [n = 258] | 86 (75-94) [n = 84] | 86 (68-96) [n = 351] | 86 (71-93) [n = 1366] | .002 | 75 (57-86) [n = 209] | 82 (68-93) [n = 394] | 79 (64-93) [n = 603] | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; CaPSURE, Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; IQR, interquartile range; LDR, low-dose-rate.

Participants with clinical stage cT to cT2bN0M0 cancer, PSA ≤20, and Group Grade 1 or 2 are categorized as having favorable-risk disease. Participants with clinical stage cT2cN0M0 cancer, PSA of 20-50, or Grade Group 3, 4 or 5 are categorized as having unfavorable-risk disease.

All P values are for overall treatment difference.

Based on the Total Illness Burden Index (range, 0-23; higher scores indicate greater severity and number of comorbid illnesses).

Biopsy Grade Group 1 is Gleason 3 + 3 = 6, Group 2 is 3 + 4 = 7, Group 3 is 4 + 3 = 7, Group 4 is 4 + 4 = 8, and Group 5 is 5 + 4 = 9 or 5 + 5 = 10.

Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function.

Medical Outcomes Short-Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) domain scores are transformed to a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function or less disability (physical function domain score is a weighted sum of 10 items; emotional well-being, 5 items; and energy and fatigue score, 4 items).

Five questions from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale are selected to create a modified domain score. Responses are transformed to a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater support.

Derived from the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Seven items are scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating increased patient choice, control, and responsibility.

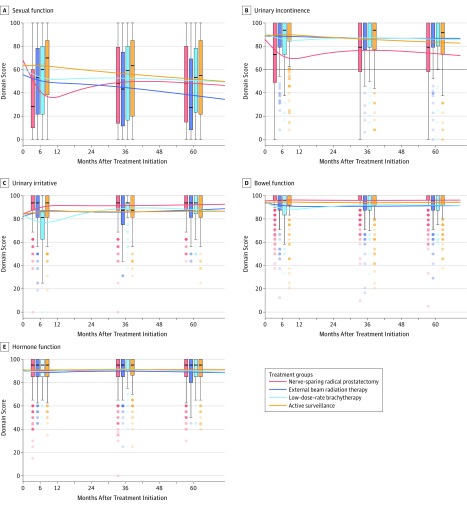

Sexual Function

Men undergoing nerve-sparing prostatectomy reported higher baseline sexual function domain scores (median score, 80) than men treated with EBRT (median score, 60), LDR brachytherapy (median score, 75), and active surveillance (median score, 75). Clinically meaningful declines in sexual function (greater than the MCID of 10-12) between median domain scores at baseline and 5 years were seen in each group (32 for nerve-sparing prostatectomy, 32 for EBRT, 22 for LDR brachytherapy, and 20 for active surveillance) (Figure 2 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Unadjusted Disease-Specific Function for Men With Favorable-Risk Disease in a Study of the Association Between Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years .

Domain scores are from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (range, 0-100; higher scores indicate better function). Boxplots illustrate the distribution of scores at 6 months, 3 years, and 5 years. The boxes indicate the lower and upper quartiles and the lines inside the boxes indicate the median. The whiskers extend to the furthest points from the lower and upper quartiles that are still within 1.5 × the interquartile range (upper quartile − lower quartile). All the points beyond 1.5 × interquartile ranges are shown as dots, the intensity of which signifies the relative number of participants with that value.

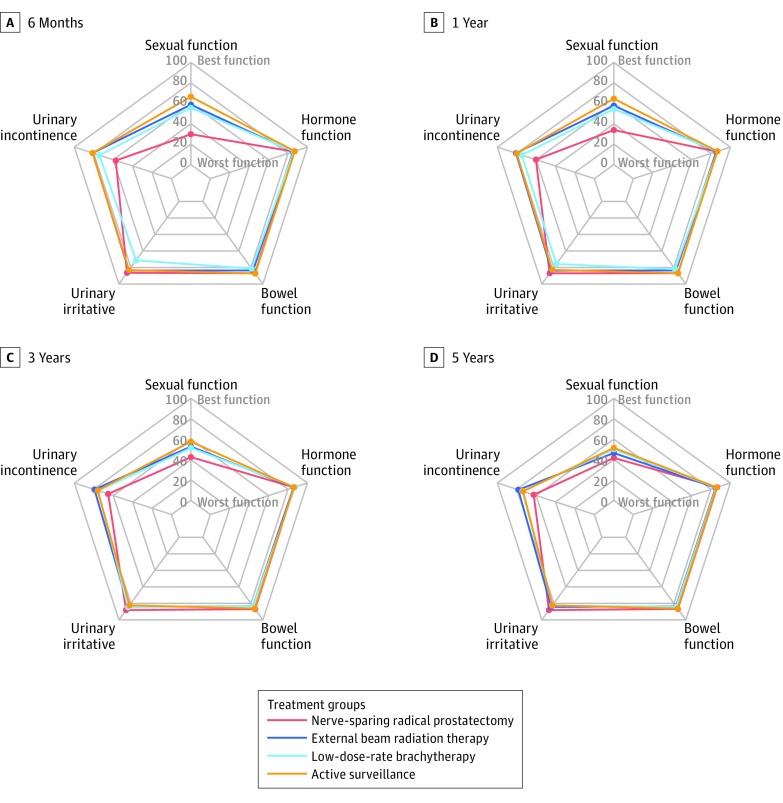

While controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, compared with active surveillance, there were clinically meaningful differences in sexual function between men who underwent active surveillance and men who underwent prostatectomy through 3 years after treatment (adjusted mean difference, −15.2 [95% CI, −18.8 to −11.5]; P < .001 at 3 years) and men who underwent LDR brachytherapy through 1 year (adjusted mean difference, −10.1 [95% CI, −14.6 to −5.7], P < .001 at 1 year), but not between men who underwent EBRT through 5 years (Figure 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Prostatectomy was also associated with clinically meaningful worse sexual function through 3 years compared with EBRT (adjusted mean difference, −10.4 [95% CI, −14.4 to −6.4]; P < .001 at 3 years) and through 1 year (adjusted mean difference, −20.6 [95% CI, −25.2 to −15.9]; P < .001 at 1 year) compared with LDR brachytherapy. Additional between-group comparisons were statistically significant, but did not meet the threshold for a clinically meaningful difference (Figure 3 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement).

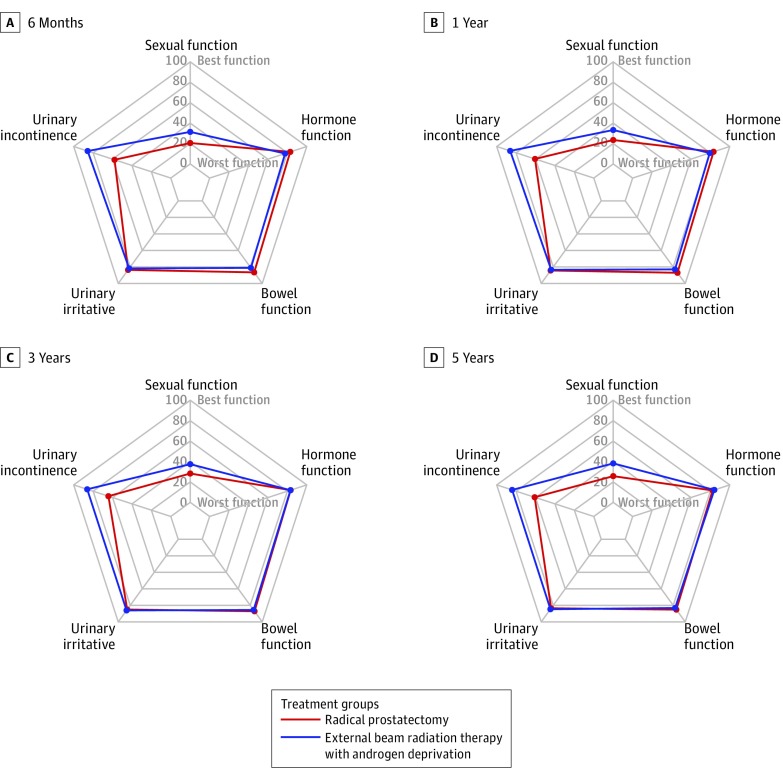

Figure 3. Adjusted Disease-Specific Functional Outcomes for Men With Favorable-Risk Disease in a Study of the Association Between Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years.

Radar plots of adjusted Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite functional domain scores. The center of each figure represents worst function (score of 0) and the outermost line represents best function (score of 100). For the sexual function domain, the minimum clinically important difference in score is 10-12; urinary incontinence domain, 6-9; urinary irritative domain, 5-7; and bowel and hormonal function domains, 4-6. The regression models were adjusted for baseline domain score, age, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, cancer characteristics, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style, and accrual site.

At 5 years, compared with men who underwent active surveillance, more men who underwent prostatectomy reported erections insufficient for intercourse (57% vs 61%; adjusted OR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.3-2.9]; P < .001) and a moderate or big problem with sexual function (24% vs 35%; adjusted OR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.3-2.8]; P < .001). Among men who reported erections sufficient for intercourse at baseline, 205 of 428 men (48%) who received nerve-sparing prostatectomy, 53 of 109 (49%) who received EBRT, 25 of 46 (54%) who received LDR brachytherapy, and 133 of 200 (66%) who underwent active surveillance retained or regained erections sufficient for intercourse at 5 years (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Urinary Function

Baseline urinary function was similar across treatment groups (Table). A clinically meaningful decline in urinary incontinence function (MCID, 6-9) was shown in men who underwent nerve-sparing prostatectomy, from a median domain score of 100 at baseline to 73 at 6 months, with limited subsequent improvement (79 at 3 and 5 years). A clinically meaningful decline in urinary irritative function (MCID, 5-7) was reported in the participants who underwent LDR brachytherapy at 6 months, from a median domain score of 94 at baseline to 81 at 6 months, with subsequent improvement (94 at 3 and 5 years). Clinically meaningful improvement was seen in participants who underwent prostatectomy, from a median score of 88 at baseline to 94 at subsequent time points (Figure 2 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

While controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, prostatectomy was associated with clinically meaningful worse urinary incontinence function through 5 years compared with active surveillance (adjusted mean difference, −10.9 [95% CI, −14.2 to −7.6]; P < .001 at 5 years), EBRT (adjusted mean difference, −15.9 [95% CI, −19.5 to −12.3]; P < .001 at 5 years), and LDR brachytherapy (adjusted mean difference, −11.6 [95% CI, −17.5 to −5.7]; P < .001 at 5 years). At 5 years, prostatectomy was associated with clinically meaningful better urinary irritative function than active surveillance (adjusted mean difference, 5.7 [95% CI, 3.9-7.4]; P < .001) and LDR brachytherapy (adjusted mean difference, 5.4 [95% CI, 1.7-9.1]; P < .001). LDR brachytherapy was associated with clinically meaningful worse incontinence function at 6 months (adjusted mean difference, −7.0 [95% CI, −11.2 to −2.8]; P < .001) and irritative function through 1 year (adjusted mean difference, −7.0 [95% CI, −10.1 to −3.9]; P < .001 at 1 year) compared with active surveillance. There were no clinically meaningful urinary function differences between participants who underwent EBRT and active surveillance at any time point (Figure 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

At 5 years, nerve-sparing prostatectomy was associated with higher rates of urinary leakage than active surveillance (10% vs 7%; adjusted OR, −1.9 [95% CI, 1.0-3.4]; P = .04). There were no statistically significant differences in moderate or big problems with urinary function, urinary frequency, or burning on urination across treatment groups at 5 years (eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement)

Bowel Function

Baseline bowel function was similar across treatment groups. Small but clinically meaningful (MCID, 4-6) declines in bowel function were reported after EBRT (from a median score of 100 at baseline to 96 at subsequent time points) and LDR brachytherapy (from a median score of 100 at baseline to 96 at 6 months and 1 year, and back to 100 at subsequent time points) (Figure 2 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

While controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, LDR brachytherapy was associated with worse bowel function through 1 year compared with active surveillance (adjusted mean difference, −5.0 [95% CI, −7.6 to −2.4]; P < .001 at 1 year) and nerve-sparing prostatectomy (adjusted mean difference, −5.0 [95% CI, − 7.5 to −2.4]; P < .001 at 1 year). There were no clinically meaningful bowel function differences between EBRT or prostatectomy and active surveillance at any time point (Figure 3 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement).

Hormonal Function

There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in hormonal function (Figure 2, Figure 3, and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement).

Additional Analyses

Men who initially underwent active surveillance who progressed to treatment reported greater functional decline than those who continued undergoing active surveillance (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Men who underwent nerve-sparing prostatectomy, EBRT, and LDR brachytherapy were compared with the subset of participants who initially chose active surveillance and did not receive a treatment at a later time point. The results were similar to the aggregated results; however, the magnitude of difference was greater for some comparisons (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Unfavorable-Risk Disease

Of 619 men with unfavorable-risk disease, 402 (65%) underwent prostatectomy and 217 (35%) underwent EBRT delivered with ADT (additional treatment details are provided in eTable 4 in the Supplement). Men treated with EBRT and ADT were older, had more comorbidities, and were less likely to be non-Hispanic white (Table).

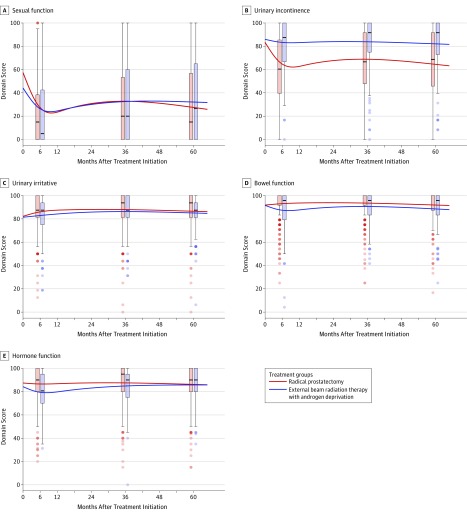

Sexual Function

Men who received EBRT delivered with ADT had worse baseline sexual function than men who received prostatectomy (Table). There were clinically meaningful declines in both treatment groups in sexual function (MCID, 10-12), with the median domain score falling from 70 to 15 for men who underwent prostatectomy and from 48 to 27 for men who underwent EBRT with ADT (Figure 4 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). When controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, EBRT with ADT was associated with statistically significantly better sexual function through 5 years than prostatectomy (Figure 5 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). The difference was clinically meaningful at 6 months (adjusted mean difference, 10.9 [ 95% CI, 6.0-15.8]; P < .001) and 5 years (adjusted mean difference, 12.5 [95% CI, 6.2-18.7]; P < .001). At 5 years, EBRT with ADT was associated with a lower likelihood of erection insufficient for penetration (75% vs 80%; adjusted OR, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2-0.8]; P = .01); however, there was no statistically significant difference in sexual bother between men who received EBRT with ADT vs prostatectomy (eTable 9 in the Supplement). Among men who reported erections sufficient for intercourse at baseline, 63 of 204 (31%) treated with prostatectomy and 37 of 80 (46%) treated with EBRT and ADT reported the ability to maintain erections sufficient for intercourse at 5 years (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Unadjusted Disease-Specific Function for Men With Unfavorable-Risk Disease in a Study of the Association Between Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years .

Domain scores are from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (range, 0-100; higher score indicate better function). Boxplots illustrate the distribution of scores at 6 months, 3 years, and 5 years. The boxes indicate the lower and upper quartiles and the lines inside the boxes indicate the median. The whiskers extend to the furthest points from the lower and upper quartiles that are still within 1.5 × the interquartile range (upper quartile − lower quartile). All the points beyond 1.5 × interquartile ranges are shown as dots, the intensity of which signifies the relative number of participants with that value.

Figure 5. Adjusted Disease-Specific Functional Outcomes for Men With Unfavorable-Risk Prostate Cancer in a Study of the Association Between Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years .

Radar plots of adjusted Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite functional domain scores. The center of each figure represents worst function (score of 0) and the outermost line represents best function (score of 100). For the sexual function domain, the minimum clinically important difference in score is 10-12; urinary incontinence domain, 6-9; urinary irritative domain, 5-7; and bowel and hormonal function domains, 4-6. The regression models were adjusted for baseline domain score, age, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, cancer characteristics, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style, and accrual site.

Urinary Function

Baseline urinary function was similar across treatment groups (Table). Men treated with prostatectomy showed a clinically meaningful decline in incontinence function (MCID, 6-9), with median domain scores falling from 100 at baseline to 69 at 5 years (Figure 4 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). When controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, EBRT with ADT was associated with statistically significantly better incontinence function than prostatectomy, which was clinically meaningful at all time points (5 years: adjusted mean difference, 23.2 [95% CI, 17.7-28.7]; P < .001; Figure 5 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). There was no statistically significant or clinically meaningful difference in urinary irritative function between treatment groups (Figure 5 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). At 5 years, EBRT with ADT was associated with lower likelihood of moderate or big problems with urinary function (13% vs 17%; adjusted OR, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2-0.8]; P = .005).

Bowel Function

Baseline bowel function was similar across treatment groups (Table). Men treated with EBRT with ADT reported a clinically meaningful decline in bowel function (MCID, 4-6), from a median domain score of 100 at baseline to a low of 92 at 1 year (Figure 4 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). When controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, EBRT with ADT was associated with clinically meaningful worse bowel function scores than prostatectomy through 1 year (adjusted mean difference, −4.1 [95% CI, −6.3 to −1.9]; P < .001 at 1 year; Figure 5 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in individual bowel symptoms through 5 years (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Hormonal Function

Baseline hormonal function was similar across treatment groups (Table). Men treated with EBRT with ADT reported a clinically meaningful decline in hormone function (MCID, 4-6), from a median domain score of 90 at baseline to a low of 81 at 6 months, with subsequent improvement to 90 at 5 years (Figure 4 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). When controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates, EBRT with ADT was associated with statistically significantly worse hormone function at 6 months and 1 year, which was only clinically meaningful at 6 months (adjusted mean difference, −5.3 [95% CI, −8.2 to −2.4]; P < .001). There was no statistically significant or clinically meaningful difference in hormone function between groups thereafter (Figure 5 and eTable 9 in the Supplement).

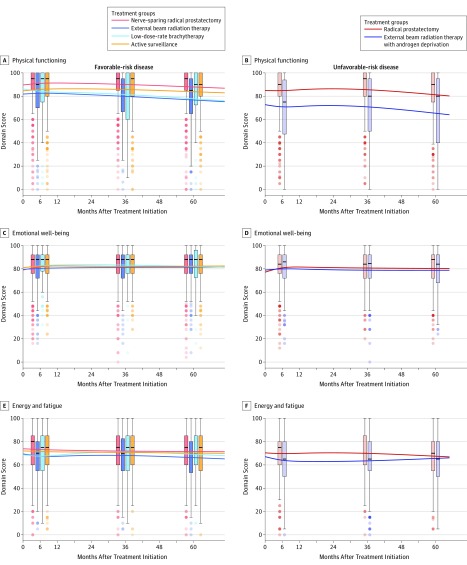

Health-Related Quality of Life

For both men with favorable-risk and men with unfavorable-risk disease, baseline SF-36 physical function score was highest for men who underwent prostatectomy and lowest for men who underwent EBRT-based treatment (Table). None of the treatment groups reported a clinically meaningful decline in physical function, emotional well-being, or energy and fatigue scores (Figure 6). When controlling for baseline scores and other covariates, there were no clinically meaningful differences between treatment groups in physical functioning, emotional well-being, or energy and fatigue (eTables 10 and 11 and eFigures 2 and 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 6. Unadjusted Health-Related Quality of Life for Men With Favorable- and Unfavorable-Risk Disease in a Study of the Association Between Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer Through 5 Years .

Domain scores are from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36. Domain scores are scaled from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating better function. A minimum clinically important difference in score is 7 on the physical functioning, 6 on the emotional well-being, and 0 on the energy and fatigue domain. The boxes indicate the lower and upper quartiles and the lines inside the boxes indicate the median. The whiskers extend to the furthest points from the lower and upper quartiles that are still within 1.5 × the interquartile range (upper quartile − lower quartile). All the points beyond 1.5 × interquartile ranges are shown as dots, the intensity of which signifies the relative number of participants with that value.

Exploratory Analyses of Effect Modification by Covariates

Interaction terms were added to multivariable models to investigate if the associations between treatment and functional outcomes differed based on baseline characteristics. Baseline function was an effect modifier for sexual function (P = .008 for favorable-risk and P = .007 for the unfavorable-risk disease), urinary incontinence (P = .009 for favorable-risk and P < .001 for unfavorable-risk disease), and urinary irritative (P < .001 for favorable-risk and P = .03 for unfavorable-risk disease) domains. Comorbidity was an effect modifier for sexual function in the favorable-risk group (P = .04) and for hormone function in the unfavorable-risk group (P = .03). For men in the unfavorable-risk group, cancer characteristics (PSA >20 or Grade Group 4-5 vs not) was an effect modifier for sexual function (P = .03). There were no statistically significant interactions associated with black race (eTables 12-15 and eFigures 4-6 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this cohort study, contemporary management strategies for localized prostate cancer were associated with distinct adverse effect profiles. While most urinary, bowel, sexual, and hormonal functional differences attenuated by 5 years, prostatectomy was associated with clinically meaningful worse urinary incontinence than other management options through 5 years for men with favorable- and unfavorable-risk prostate cancer. For men with unfavorable-risk disease, prostatectomy was also associated with clinically meaningful worse sexual function at 5 years than EBRT delivered with ADT. However, irrespective of whether they received prostatectomy or EBRT with ADT, fewer than half of men with unfavorable-risk disease reported the ability to maintain erections sufficient for intercourse at 5 years.

While intermediate-term functional outcomes of prostate cancer treatments have been studied in the randomized ProtecT trial,31 the current study differs in several respects. The ProtecT trial from the United Kingdom randomized men to undergo active surveillance, nerve-sparing prostatectomy with an open retropubic approach, or 74 Gy 3-dimensional conformal EBRT administered with ADT. In contrast, most men in the current study underwent prostatectomy with robotic assistance and received higher-dose EBRT delivered with intensity-modulated radiation therapy, daily image guidance, and risked-based use of ADT. The current study also included a group of men treated with LDR brachytherapy. Additionally, 23% of this cohort was not white, compared with 1% in the ProtecT study, and 52% had Grade Group 1 disease, compared with 77% in the ProtecT trial.31

Differences in treatment details may explain some of the differences in adverse effect profiles between this study and the ProtecT study. First, there were fewer sexual adverse effects after EBRT for men with favorable-risk disease in the current study than in the ProtecT trial, likely because the favorable-risk group in the current study did not receive ADT and men in the ProtecT trial received 3 to 6 months of ADT.4,31 Second, there were fewer bowel adverse effects after EBRT for men with favorable-risk disease in the current study than the ProtecT trial, likely because most participants in this study received intensity-modulated radiation therapy with image guidance, which delivers less radiation to the bowel than the 3-dimensional conformal radiation used in the ProtecT trial.32,33 Despite the use of robotic surgery in 75% of participants who underwent prostatectomy in this study, there were significant declines in sexual and urinary incontinence scores in these participants, which was also seen in the ProtecT trial, suggesting that men undergoing prostatectomy, whether robotic or open, are at risk for these adverse effects.

Men in all treatment groups in this study experienced clinically meaningful declines in sexual function over time, including those who underwent active surveillance. This decline was in part due to progression to treatment and in part due to age-related functional changes. In both the favorable-risk and unfavorable-risk disease groups, the effect on sexual function was greatest in men treated with prostatectomy, which is consistent with findings from ProtecT and other studies.3,4,5,7,31

Urinary changes after treatment in this study were also consistent with findings from other studies.3,4,5,7,31 Decrements in urinary incontinence after prostatectomy remained clinically meaningful throughout 5 years, while men treated with LDR brachytherapy experienced clinically meaningful declines in urinary irritative function and bowel function during the first year.

Treatment intensity and options vary by cancer severity. By analyzing adverse effects for men with favorable- and unfavorable-risk disease separately, the outcomes of relevant management options for each risk level were compared, making the results more actionable. For example, prostatectomy was associated with worse 5-year sexual function outcomes than EBRT in the unfavorable-risk group, but not in the favorable-risk group, who routinely underwent nerve-sparing prostatectomy. Similarly, men with unfavorable-risk disease who received EBRT with ADT reported clinically meaningful transient bowel and hormonal adverse effects, which is likely because all of these men received ADT and some received pelvic nodal radiation, which delivers radiation to the bowel, while men treated with EBRT with favorable-risk disease did not report clinically meaningful bowel and hormonal function changes.

Five-year disease-specific survival for localized prostate cancer approaches 100%.34 Because the treatment options evaluated in this study were associated with similar prostate cancer survival and global health-related quality of life through the first 5 years, the differences in urinary, bowel, sexual, and hormonal function are the most salient outcomes during this period and may drive patient treatment selection. Other factors, including patient preference, perception of long-term oncologic effectiveness, time commitment for treatment and recovery, out-of-pocket expenses, salvage treatment options, and provider biases and recommendation, also affect treatment choice.35,36

Strengths of the study include its population-based, longitudinal design and focus on contemporary surgical, radiotherapy, and surveillance techniques, which make the results representative of disease-specific function after current management of localized prostate cancer in the United States. The sample size was adequate to report functional outcomes by treatment within disease-risk strata to better inform patients and providers. Analyzing the active surveillance group in an intention-to-treat fashion highlighted the adverse effects experienced in this group, in which most men had repeat biopsies and 25% underwent definitive treatment over the 5-year follow-up period.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as with all observational studies, confounding by indication is likely. To minimize bias, models adjusted for baseline characteristics and a wide range of variables associated with treatment selection. Second, patient function is reported up to 5 years after treatment, which is generally the period of greatest functional change, but important differences may exist among treatments between data collection periods and at later points. Third, there is the potential for type II errors given the relatively small sample size for some treatment-specific estimates. Fourth, the analytic models predict average function and used clinical judgment and published thresholds when interpreting clinically meaningful differences in functional domain scores. However, an individual’s function and personal experience may vary. Fifth, some data were missing; however, domain scores could be calculated as long as 80% of questions were completed within a particular domain and multiple imputation was used to fill in missing regression model covariate values. Sixth, this study focused on the most common and appropriate management strategies for localized prostate cancer at each risk level,1,2 but did not evaluate uncommon and investigational strategies, such as cryotherapy and high-dose-rate brachytherapy.

Conclusions

In this cohort of men with localized prostate cancer, most functional differences associated with contemporary management options attenuated by 5 years. However, men undergoing prostatectomy reported clinically meaningful worse incontinence through 5 years than all other treatment options, and men undergoing prostatectomy for unfavorable-risk disease reported worse sexual function at 5 years than men who underwent EBRT and ADT.

eMethods and eResults

References

- 1.Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(5):479-505. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. 2018;199(3):683-690. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen RC, Basak R, Meyer AM, et al. Association between choice of radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or active surveillance and patient-reported quality of life among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1141-1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group . Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1425-1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Punnen S, Cowan JE, Chan JM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. Long-term health-related quality of life after primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: results from the CaPSURE registry. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):600-608. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelefsky MJ, Poon BY, Eastham J, Vickers A, Pei X, Scardino PT. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life after surgery, conformal brachytherapy, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118(1):85-91. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(18):1358-1367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ, et al. Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1126-1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barocas DA, Chen V, Cooperberg M, et al. Using a population-based observational cohort study to address difficult comparative effectiveness research questions: the CEASAR study. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(4):445-460. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Litwin MS, et al. ; CaPSURE Investigators . The contemporary management of prostate cancer in the United States: lessons from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor (CapSURE), a national disease registry. J Urol. 2004;171(4):1393-1401. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000107247.81471.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute About the SEER registries. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program website. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- 13.Lee DJ, Barocas DA, Zhao Z, et al. Contemporary prostate cancer radiation therapy in the United States: patterns of care and compliance with quality measures. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2018;8(5):307-316. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avulova S, Zhao Z, Lee D, et al. The Effect of nerve sparing status on sexual and urinary function: 3-year results from the CEASAR study. J Urol. 2018;199(5):1202-1209. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76(5):1245-1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. ; PROSTQA Consortium . Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101-105. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II: psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247-263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayadevappa R, Malkowicz SB, Wittink M, Wein AJ, Chhatre S. Comparison of distribution- and anchor-based approaches to infer changes in health-related quality of life of prostate cancer survivors. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):1902-1925. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01395.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman RM, Gilliland FD, Eley JW, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advanced-stage prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(5):388-395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson TK, Gilliland FD, Hoffman RM, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in functional outcomes in the 5 years after diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4193-4201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litwin MS, Greenfield S, Elkin EP, Lubeck DP, Broering JM, Kaplan SH. Assessment of prognosis with the total illness burden index for prostate cancer: aiding clinicians in treatment choice. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1777-1783. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817-830. doi: 10.2307/1912934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber PJ. The Behavior Of Maximum Likelihood Estimates Under Nonstandard Conditions. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705-714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77-84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Ware JE Jr. Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision-making styles. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(5):497-504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group . 10-Year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang-Chesebro A, Xia P, Coleman J, Akazawa C, Roach M III. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy improves lymph node coverage and dose to critical structures compared with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(3):654-662. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Neil BHK, Koyama T, Alvarez J, et al. Patient reported comparative effectiveness of contemporary intensity modulated radiotherapy versus external beam radiotherapy of the mid-1990's for localized prostate cancer. Urol Pract. 2018;5(6):471-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmboe ES, Concato J. Treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer: asking men what’s important. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(10):694-701. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90842.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anandadas CN, Clarke NW, Davidson SE, et al. ; North West Uro-oncology Group . Early prostate cancer—which treatment do men prefer and why? BJU Int. 2011;107(11):1762-1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods and eResults