Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the associations between secondhand aerosol exposure from electronic cigarettes, susceptibility to tobacco use, and exposure to e-cigarette marketing among never tobacco users.

The prevalence of current electronic cigarette use among US high school students increased dramatically from 11.7% in 2017 to 20.8% in 2018.1 Exposure to secondhand aerosol (SHA) from e-cigarettes is not harmless, as e-cigarette aerosol contains nicotine and potentially harmful substances, including carbonyl compounds, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, heavy metals, and glycols.2 e-Cigarette use may serve as a gateway to cigarette initiation,2 and e-cigarette makers have significantly increased their advertising expenditures in recent years.3 Exposure to SHA may increase the curiosity about e-cigarettes and perceived pervasiveness of e-cigarette marketing and further elevate the susceptibility of tobacco use among never tobacco users.2 This study reports the trends in self-reported SHA exposure among US adolescents and examined the associations between SHA, susceptibility to tobacco use, and exposure to e-cigarette marketing among never tobacco users.

Methods

The National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) is a cross-sectional survey of US middle and high school students using a stratified, 3-stage cluster sampling procedure. Students were queried about exposure to SHA in an indoor or outdoor public place in the past 30 days.4 Given the use of deidentified data, the University of Nebraska institutional review board determined this study to be non–human subjects research.

Weighted estimates and 95% CIs of the prevalence of SHA were reported using Taylor series variance estimation. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine statistically significant differences using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). All P values were 2-tailed, and a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

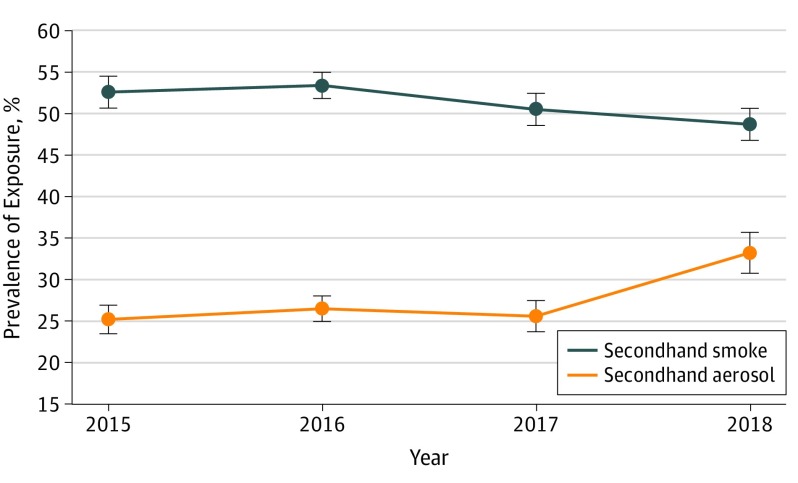

This study included 76 447 respondents from the combined 2015 to 2018 NYTS; 37 439 (weighted percentage, 49.1%) were female, 41 507 (weighted percentage, 55.9%) were high school–aged, 35 525 (weighted percentage, 56.5%) were non-Hispanic white, 11 441 (weighted percentage, 13.3%) were non-Hispanic black, and 21 017 (weighted percentage, 24.6%) were Hispanic. The prevalence of SHA exposure among middle and high school students significantly increased from 2017 to 2018 (2017: weighted estimate, 25.6% [6.7 million]; 95% CI, 23.7-27.5; 2018: weighted estimate, 33.2% [8.5 million]; 95% CI, 30.8-35.7; P < .001) after being stable from 2015 to 2017 (Figure). The increase of SHA exposure from 2017 to 2018 was observed across sociodemographic groups. In contrast, the prevalence of exposure to secondhand smoke declined from 2015 to 2018. Among 2018 NYTS respondents who never used tobacco (n = 12 324), students who reported SHA exposure (compared with no exposure) had higher odds of susceptibility to use e-cigarettes (weighted estimate, 38.8% vs 21.0%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.2) and cigarettes (weighted estimate, 30.7% vs 21.2%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-1.8) and higher odds of reporting exposure to e-cigarette marketing (Table).

Figure. Trends in Prevalence of Secondhand Aerosol Exposure and Secondhand Smoke Exposure Among 76 447 National Youth Tobacco Survey Respondents From 2015 to 2018.

Weighted estimates and 95% CIs were reported by taking the complex survey design (sampling weight, stratum, and cluster) into account using Taylor series variance estimation. Multivariable logistic regressions were performed to assess the temporal trend of exposure to secondhand aerosol and secondhand smoke, where age, sex, and race/ethnicity were covariates. Exposure to secondhand aerosol was assessed with the question, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you breathe the aerosol from someone who was using an electronic cigarette in an indoor or outdoor public place?” with response options of 0 days, 1 to 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 5 to 9 days, 10 to 19 days, 20 to 29 days, and all 30 days. Respondents who reported 1 day or more of exposure were categorized as having secondhand aerosol exposure. Exposure to secondhand smoke was assessed with the question, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you breathe the smoke from someone who was smoking tobacco products in an indoor or outdoor public place?” with the same response options as secondhand aerosol exposure. Respondents who reported 1 day or more were categorized as having secondhand smoke exposure. The prevalence of exposure to secondhand smoke in 2015 was 52.6%; in 2016, 53.4%; in 2017, 50.5%; and in 2018, 48.7%. The prevalence of exposure to secondhand aerosol in 2015 was 25.2%; in 2016, 26.5%; in 2017, 25.6%; and in 2018, 33.2%.

Table. Associations Between Exposure to Secondhand Aerosol (SHA), Susceptibility to Tobacco Use, and Exposure to Electronic Cigarette Marketing Among 12 324 Never Tobacco Users in the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Surveya.

| Variable | Weighted % (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SHA | SHA | |||

| Susceptibility | ||||

| e-Cigarette use | 21.0 (19.8-22.3) | 38.8 (35.8-41.9) | 1.9 (1.7-2.2)b | <.001 |

| Cigarette use | 21.2 (19.9-22.6) | 30.7 (28.1-33.3) | 1.6 (1.3-1.8)b | <.001 |

| Exposure to e-cigarette advertisements and promotion | ||||

| Internet | 24.5 (23.4-25.6) | 36.1 (34.1-38.2) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8)c | <.001 |

| Newspaper/magazine | 12.2 (11.3-13.2) | 17.8 (15.8-19.7) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8)c | <.001 |

| Store | 36.8 (35.4-38.2) | 51.3 (49.0-53.7) | 1.4 (1.3-1.6)c | <.001 |

| Television/movie | 22.5 (21.1-24.0) | 28.5 (26.5-30.5) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6)c | <.001 |

Separate multivariable logistic regression was performed among students who reported never using any tobacco (ie, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, hookahs, tobacco pipes, snus, or dissolvables). No SHA served as the reference group.

Susceptibility to e-cigarette and cigarette use was assessed by not affirmatively endorsing 1 of 3 questions: “Do you think that you will try an (e-)cigarette soon?” “Do you think you will use an (e-)cigarette in the next year?” and “If one of your best friends were to offer you an (e-)cigarette, would you use it?” Adjusted odds ratios were adjusted by sex, age, race/ethnicity, tobacco use by a household member, exposure to secondhand smoke, harm perception of e-cigarette use, and exposure to e-cigarette advertisements.

Exposure to e-cigarette advertising and promotion was assessed by questions about how often they see advertisements or promotions for e-cigarettes when using the internet, reading newspapers or magazines, going to the store, and watching television or movies. Adjusted odds ratios were adjusted by sex, age, race/ethnicity, tobacco use by a household member, exposure to secondhand smoke, and harm perception of e-cigarette use.

Discussion

This study found a surge in self-reported SHA exposure from 2017 to 2018 among US middle and high school students, with an estimate of nearly 1 in 3 US youths exposed to SHA. The surge is in sharp contrast to a stable trend of SHA from 2015 to 2017.4 Nineteen states and hundreds of localities have taken actions to restrict e-cigarette use in 100% smoke-free venues.5 However, most youths are not covered by vape-free laws, which could enlarge tobacco-related disparities.

This study reports a strong association of SHA exposure with susceptibility to e-cigarettes and a moderate association of SHA exposure with susceptibility to smoking among never tobacco users. Exposure to SHA may renormalize tobacco use behaviors and reduce the perceived harm, resulting in increased susceptibility to tobacco use. This study also reports that students with SHA exposure had elevated perceived pervasiveness of e-cigarette marketing. Students exposed to SHA (compared with those not exposed to SHA) might live in an environment with excessive tobacco marketing and might have increased receptivity and recall to e-cigarette marketing.6 Furthermore, e-cigarettes and cigarettes are commonly promoted together in a retail setting,2 and exposure to e-cigarette marketing can further increase the susceptibility to e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking among adolescents.2 Future longitudinal studies are needed to assess whether SHA exposure leads to tobacco initiation and progression to heavy use.

This study has limitations. Secondhand aerosol exposure is self-reported and subject to recall bias. The NYTS data are cross-sectional, and thus, causal inference cannot be established. Comprehensive tobacco control strategies, including smoke-free and vape-free laws, raising the minimum legal age of tobacco sales to 21 years, and educational campaigns, are needed to protect youth from exposure to SHA.

References

- 1.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1276-1277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh T, Marynak K, Arrazola RA, Cox S, Rolle IV, King BA. Vital signs: exposure to electronic cigarette advertising among middle school and high school students—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(52):1403-1408. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6452a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Marynak KL, Trivers KF, King BA. Exposure to secondhand smoke and secondhand e-cigarette aerosol among middle and high school students. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E42. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation States and municipalities with laws regulating use of electronic cigarettes. http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/ecigslaws.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2019.

- 6.Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Kehl L, Herzog TA. Receptivity to e-cigarette marketing, harm perceptions, and e-cigarette use. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(1):121-131. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]