This randomized clinical trial of patients previously treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis assesses the efficacy of different dupilumab regimens in maintaining response after 16 weeks of initial treatment.

Key Points

Question

Do dupilumab regimens less frequent than once weekly or every 2 weeks maintain long-term efficacy and safety?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 422 patients, high-responding patients previously treated for 16 weeks with 300 mg of dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks who continued those regimens had the most consistent efficacy; patients taking lower-dose regimens (every 4 or 8 weeks) or placebo had a dose-dependent reduction in response and no safety advantage.

Meaning

The approved regimen (every 2 weeks) maintained clinical response and is therefore recommended for long-term treatment.

Abstract

Importance

The dupilumab regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks is approved for uncontrolled, moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of different dupilumab regimens in maintaining response after 16 weeks of initial treatment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis (LIBERTY AD SOLO-CONTINUE) was a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial conducted from March 25, 2015, to October 18, 2016, at 185 sites in North America, Europe, Asia, and Japan. Patients with moderate to severe AD who received dupilumab treatment and achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores (EASI-75) at week 16 in 2 previous dupilumab monotherapy trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2) were rerandomized in SOLO-CONTINUE. After completing SOLO-CONTINUE, patients were followed up for up to 12 weeks or enrolled in an open-label extension. Data were analyzed from December 5 to 12, 2016.

Interventions

High-responding patients treated with dupilumab in SOLO were rerandomized 2:1:1:1 to continue their original regimen of dupilumab, 300 mg, weekly or every 2 weeks or to receive dupilumab, 300 mg, every 4 or 8 weeks or placebo for 36 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percentage change in EASI score from baseline during the SOLO-CONTINUE trial, percentage of patients with EASI-75 at week 36, and safety.

Results

Among the 422 patients (mean [SD] age, 38.2 [14.5] years; 227 [53.8%] male), continuing dupilumab treatment once weekly or every 2 weeks maintained optimal efficacy, with negligible change in percent EASI improvement from SOLO 1 and 2 baseline during the SOLO-CONTINUE trial (−0.06%; P < .001 vs placebo); percent change with the other regimens dose-dependently worsened (dupilumab every 4 weeks, −3.84%; dupilumab every 8 weeks, −6.84%; placebo, −21.67%). More patients taking dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks (116 of 162 [71.6%]; P < .001 vs placebo) maintained EASI-75 response than those taking dupilumab every 4 weeks (49 of 84 [58.3%]) or every 8 weeks (45 of 82 [54.9%]) or those taking placebo (24 of 79 [30.4%]). Overall adverse event incidences were 70.7% in the weekly or every 2 weeks group, 73.6% in the every 4 weeks group, 75.0% in the every 8 weeks group, and 81.7% in the placebo group. Treatment groups had similar conjunctivitis rates. Treatment-emergent antidrug antibody incidence was lower with more frequent dupilumab dose regimens (11.3% in the placebo group and 11.7%, 6.0%, 4.3%, and 1.2% in the dupilumab every 8 weeks, every 4 weeks, every 2 weeks, and weekly groups, respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this trial, continued response over time was most consistently maintained with dupilumab administered weekly or every 2 weeks. Longer dosage intervals and placebo resulted in a diminution of response for both continuous and categorical end points. No new safety signals were observed. The approved regimen of 300 mg of dupilumab every 2 weeks is recommended for long-term treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02395133

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with eczematous lesions and intense pruritus1,2 associated with skin barrier dysfunction and immune dysregulation mediated by type 2 inflammatory cytokines.3 Dupilumab is a fully human VelocImmune-derived4,5 human monoclonal antibody against interleukin (IL) 4 receptor α that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling. Dupilumab is approved for patients 12 years or older in the United States with moderate to severe AD inadequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable; adults with AD that is inadequately controlled with existing therapies in Japan; patients 12 years or older with moderate to severe AD who are candidates for systemic therapy in the European Union6,7; as an add-on treatment for patients 18 years or older with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in the United States; and certain patients with asthma in multiple countries.8,9,10,11 Efficacy and safety of dupilumab have also been found in a clinical trial of eosinophilic esophagitis,12 thus demonstrating the importance of IL-4 and IL-13 as key cytokines involved in multiple type 2 inflammatory diseases.13

In previous studies,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 including 2 identically designed, 16-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 monotherapy studies in adults with moderate to severe AD and inadequate response to topical treatments (Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis [LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, hereafter referred to as SOLO 1] and Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis [LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, hereafter referred to as SOLO 2])14 and phase 3 trials with concomitant topical corticosteroids for 52 weeks or less, dupilumab significantly improved clinical signs, itch, other symptoms, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression and was well tolerated.

Once AD clinical response is achieved, it is unknown whether control could be maintained with longer dosage intervals or even treatment withdrawal. Psoriasis studies suggest that intermittent administration of biologics can reduce their efficacy and increase risk of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) or of safety issues.21,22,23

The objectives of Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis (LIBERTY AD SOLO-CONTINUE, hereafter referred to as SOLO-CONTINUE) were to evaluate maintenance of clinical response and long-term safety of dupilumab monotherapy at the original (300 mg every week or every 2 weeks) or less frequent regimens or drug withdrawal for an additional 36 weeks in patients treated with dupilumab who achieved predefined treatment-success end points in SOLO 1 or 2.

Methods

Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

This randomized clinical trial (study protocol in Supplement 1) was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki24 and are consistent with International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and applicable regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before the study, and all data were deidentified. Institutional review boards and independent ethics committees of each of the participating institutions reviewed and approved the protocol, informed consent form, and patient information before study initiation. The Independent Data Monitoring Committee monitored patient safety. This trial followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

SOLO-CONTINUE was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of dupilumab conducted at 185 sites in North America, Europe, and Asia from March 25, 2015, to October 18, 2016. Eligible participants were dupilumab-treated patients who had achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 or 75% or greater improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores (EASI-75) at week 16 of the preceding SOLO studies.14 Participants were rerandomized 2:1:1:1 on SOLO-CONTINUE day 1 (SOLO week 16) as follows: patients either continued their original SOLO regimen (ie, 300 mg of subcutaneous dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks) or were assigned to a less frequent regimen (300 mg every 4 or 8 weeks) or placebo for 36 weeks (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Randomization was stratified by region (North America, Europe, Asia, and Japan) and baseline IGA score (0, 1, or >1) using a central interactive voice response system. Randomization was performed by a predefined random number sequence with block size of 5 within each combination of stratification factors (dose of dupilumab received in parent study, region, and IGA scores).

SOLO-CONTINUE was blinded to all individuals until prespecified unblinding except for the interactive voice response system statistician (administered randomization sequence) and the independent data monitoring committee statistician and members, none of whom were involved in study design, management, or data analyses. For the every 2, 4, and 8 weeks regimens, matching placebo was administered in the weeks that dupilumab was not administered. Blinded study-drug kits were coded with a medication numbering system.

Patients were required to apply moisturizers 2 or more times daily throughout the study. Topical or systemic rescue medications to control intolerable AD symptoms could be used at investigator discretion. Patients discontinued use of the study drug when using systemic rescue medication (eMethods in Supplement 2).

End Points

The continuous coprimary end point, based on percentage change in EASI score from SOLO baseline, assessed the difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline (week 0) and SOLO-CONTINUE week 36. In SOLO, the continuous EASI end point was assessed as percentage change from the baseline EASI score (ie, baseline EASI score was considered 100%). In SOLO-CONTINUE, the same method (ie, percentage change) and the same reference point (SOLO baseline EASI score) were used, but the continuous coprimary end point reported the additional changes that occurred after SOLO (ie, during SOLO-CONTINUE). The categorical coprimary end point was the percentage of patients at week 36 who maintained EASI-75 from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline (among patients with EASI-75 at SOLO week 16). Key secondary end points at week 36 included percentages of patients with IGA scores maintained within 1 point of SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, IGA scores of 0 or 1 among patients with IGA scores of 0 or 1 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, and a 3-point or greater worsening of Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 35 among patients with SOLO-CONTINUE baseline Peak Pruritus NRS scores of 7 or less. A technical issue with the interactive voice response system collecting patient-reported pruritus data resulted in considerable missing pruritus data at week 36; because Peak Pruritus NRS scores were stable in all dose groups by week 35, this was deemed to be a suitable end-of-treatment time point for Peak Pruritus NRS analyses (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Trough concentrations of functional dupilumab were assessed in serum samples collected at SOLO-CONTINUE weeks 0, 4, 12, 24, and 36. Treatment-emergent ADAs were assessed at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 36 (eMethods in Supplement 2). Safety assessments included treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, and AEs that led to study treatment withdrawal.

Statistical Analysis

Approximately 420 patients were expected to enroll based on SOLO sample sizes and anticipated response rates (eMethods in Supplement 2). To compare each dupilumab treatment group with placebo, significance was set to a 2-sided P < .05. To control for multiplicity, the coprimary and key secondary end points were assessed in a hierarchical manner (eMethods in Supplement 2). Other secondary and post hoc end points were not controlled for multiplicity; their P values are nominal.

Categorical end points were analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted by randomization strata (disease severity and region) and SOLO treatment regimens; patients were considered to be nonresponders from the time of rescue medication use or withdrawal. For continuous end points, data were treated as missing after rescue medication use or early discontinuation; missing data were imputed using multiple imputation with analysis of covariance, with treatment group, SOLO treatment regimen, randomization strata (disease severity), and SOLO-CONTINUE baseline as covariates. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the coprimary end points (eMethods in Supplement 2). Safety, trough concentrations of functional dupilumab, and treatment-emergent ADAs were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patient Disposition and Demographics

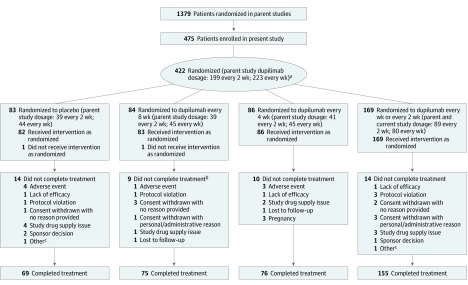

A total of 1379 patients were randomized in SOLO (dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, n = 919; placebo, n = 460). At SOLO week 16, a total of 525 patients (38.1%) achieved EASI-75 or had an IGA score of 0 or 1 (dupilumab weekly, 236 of 462 [51.1%]; dupilumab every 2 weeks, 227 of 457 [49.7%]; placebo, 62 of 460 [13.5%]), of whom 475 met SOLO-CONTINUE eligibility criteria and were enrolled. Of these, 53 placebo-treated SOLO patients did not meet the eligibility criteria; for the purposes of maintaining blinding, these patients were assigned to a separate placebo cohort, not randomized in SOLO-CONTINUE, and not included in these analyses. Therefore, 422 patients (mean [SD] age, 38.2 [14.5] years; 227 [53.8%] male) treated with dupilumab in SOLO were rerandomized in SOLO-CONTINUE to either continue their original treatment regimen (weekly, n = 89; every 2 weeks, n = 80) or to take dupilumab every 4 weeks (n = 86), dupilumab every 8 weeks (n = 84), or placebo (n = 83) in this intent-to-treat analysis (Figure 1). Treatment groups had similar baseline characteristics (Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). A total of 155 of 169 patients (91.7%) in the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks group, 76 of 86 patients (88.4%) in the every 4 weeks group, 75 of 84 patients (89.3%) in the every 8 weeks group, and 69 of 83 patients (83.1%) in the placebo group completed study treatment.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

aThere were 53 placebo-treated patients from the Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO 1) and Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO 2) who met the eligibility criteria; for the purposes of maintaining blinding, these patients were assigned to a separate placebo cohort, not randomized in Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO-CONTINUE), and therefore not included in these analyses. Two randomized patients (placebo and dupilumab every 8 weeks) withdrew before receiving the study drug. Two patients were erroneously randomized (placebo and dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks); they had not achieved 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores or Investigator’s Global Assessment scores of 0 or 1 at SOLO week 16 and were excluded from per-protocol efficacy analyses but were included in the primary (intention-to-treat) analyses.

bOne patient withdrew consent shortly after randomization and was not entered in the end of treatment page of the electronic data capture; therefore, this individual was not counted in the subcategories for reason for discontinuing study treatment.

cThe categories with 1 patient overall were grouped together, including the categories of patient had been taking oral corticosteroids; therefore, study drug injection could not be administered at week 36 and early rollover into protocol of the open-label extension study.

Table 1. SOLO-CONTINUE Baseline Characteristics (Full Analysis Set)a.

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 83) | Dupilumab, 300 mg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 8 wk (n = 84) | Every 4 wk (n = 86) | Weekly or Every 2 wk (n = 169) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), yb | 37 (27.0-46.0) | 35 (26.0-46.5) | 36 (24.0-49.0) | 36 (26.0-48.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 54 (65.1) | 56 (66.7) | 64 (74.4) | 124 (73.4) |

| Black/African American | 7 (8.4) | 8 (9.5) | 4 (4.7) | 7 (4.1) |

| Asian | 17 (20.5) | 18 (21.4) | 16 (18.6) | 31 (18.3) |

| Other | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (3.0) |

| Not reported or missing | 3 (3.6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 51 (61.4) | 51 (60.7) | 43 (50.0) | 82 (48.5) |

| Female | 32 (38.6) | 33 (39.3) | 43 (50.0) | 87 (51.5) |

| Duration of AD at baseline, y | ||||

| <26 | 37 (44.6) | 53 (63.1) | 44 (51.2) | 81 (47.9) |

| ≥26 | 44 (53.0) | 30 (35.7) | 42 (48.8) | 87 (51.5) |

| Missing | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| EASI-75 or IGA score of 0 or 1 at baseline | ||||

| No | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Yes | 82 (98.8) | 84 (100) | 86 (100) | 168 (99.4) |

| IGA score | ||||

| 0 | 8 (9.6) | 9 (10.7) | 10 (11.6) | 18 (10.7) |

| 1 | 55 (66.3) | 55 (65.5) | 58 (67.4) | 111 (65.7) |

| 2 | 19 (22.9) | 18 (21.4) | 12 (14.0) | 37 (21.9) |

| 3 | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 6 (7.0) | 3 (1.8) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EASI-75 at baseline | ||||

| No | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) | 7 (4.1) |

| Yes | 79 (95.2) | 82 (97.6) | 84 (97.7) | 162 (95.9) |

| EASI score, mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.31) | 2.3 (2.33) | 2.8 (3.31) | 2.6 (2.92) |

| Percent change in EASI score from parent study baseline, mean (SD), % | −91.2 (8.21) | −90.8 (9.32) | −91.2 (8.07) | −91.3 (9.34) |

| Weekly Peak Pruritus NRS score, mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.11) | 2.7 (2.27) | 3.1 (2.16) | 2.8 (1.92) |

| Percent BSA affected, mean (SD), % | 8.1 (8.21) | 7.9 (9.04) | 9.3 (10.51) | 7.9 (9.02) |

| SCORAD score, mean (SD) | 16.8 (10.03) | 17.1 (9.41) | 17.5 (10.59) | 17.1 (10.49) |

| Total scores, mean (SD) | ||||

| POEM | 6.1 (5.43) | 6.8 (5.88) | 6.1 (5.11) | 6.4 (5.30) |

| DLQI | 3.4 (4.25) | 3.0 (3.76) | 3.2 (3.93) | 3.4 (4.21) |

| HADSc | 5.9 (6.36) | 7.1 (6.87) | 7.3 (7.53) | 6.4 (5.94) |

| EQ-5D pain or discomfortd | ||||

| None | 60 (73.2) | 60 (71.4) | 63 (73.3) | 126 (74.6) |

| Moderate | 21 (25.6) | 24 (28.6) | 23 (26.7) | 42 (24.9) |

| Extreme | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; EASI-75, 75% or greater improvement in EASI from baseline; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimensional Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; IQR, interquartile range; SOLO-CONTINUE, Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; SCORAD, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of study participants unless otherwise indicated. Baseline is per baseline of SOLO-CONTINUE.

Median age is as per baseline of the current study; some patients had birthdays between baseline of the parent study and baseline of the current study.

Placebo, n = 78; 300 mg of dupilumab every 8 weeks, n = 81; 300 mg of dupilumab every 4 weeks, n = 75; and 300 mg of dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, n = 164.

Placebo, n = 82.

Efficacy

Eczema Area and Severity Index

Patients who received dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks during SOLO and throughout SOLO-CONTINUE had nearly no diminution in efficacy during SOLO-CONTINUE. At SOLO-CONTINUE baseline (end of SOLO), patients taking dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had EASI least squares mean improvement of 91.5% from SOLO baseline; EASI improvement was maintained at 91.4% from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 36 (−0.06% change from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 36 [continuous coprimary end point]) (Figure 2A and eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). In contrast, patients assigned to the placebo group in SOLO-CONTINUE had a 21.7% decrease from the EASI improvement achieved in SOLO (Table 2 and Figure 2A). Differences in percentage change in EASI score from SOLO baseline appeared to be dose dependent for treatment administration weekly or every 2 weeks compared with every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks (Table 2 and Figure 2A). Post hoc analyses showed no apparent difference between dupilumab weekly and every 2 weeks in maintenance of clinical response (eFigure 2B in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Maintenance of Improvement in Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes and Rescue Medication Use in the Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO-CONTINUE).

Outcome measures included the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores. A, Least squares (LS) mean percent change in EASI score from baseline of Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO 1) or Study of Dupilumab Monotherapy Administered to Adult Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (SOLO 2) baseline during SOLO-CONTINUE: difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 36. B, The LS mean percent change in Peak Pruritus NRS score from SOLO baseline during SOLO-CONTINUE: difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 35. C, The LS mean change in POEM score from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 36. D, The LS mean change in DLQI score from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 36. E, The LS mean change in HADS score from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 36. F, Cumulative percentage of patients using rescue medication from baseline in to week 36 in SOLO-CONTINUE. A-E, Negative values indicate a diminution of response. Error bars indicate SEs.

Table 2. Dupilumab Efficacy.

| End Point | Placebo (n = 83) | Dupilumab, 300 mg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 8 wk (n = 84) | Every 4 wk (n = 86) | Weekly or Every 2 wk (n = 169) | ||

| Coprimary end points | ||||

| Percent change in EASI score from SOLO baseline: difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 36, LS mean (SE) | −21.67 (3.13) | −6.84 (2.43)a | −3.84 (2.28)a | −0.06 (1.74)a |

| Patients with EASI-75 at week 36 among patients with EASI-75 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, No./total No. (%) | 24/79 (30.4) | 45/82 (54.9)b | 49/84 (58.3)a | 116/162 (71.6)a |

| Key secondary end points | ||||

| Among patients with IGA score of 0 or 1 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, No./total No. (%) | ||||

| Patients with IGA score maintained within 1 point of baseline at week 36 | 18/63 (28.6) | 32/64 (50.0)c | 41/66 (62.1)a | 89/126 (70.6)a |

| Patients with IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 36 | 9/63 (14.3) | 21/64 (32.8)c | 29/66 (43.9)a | 68/126 (54.0)a |

| Patients with increase of ≥3 in Peak Pruritus NRS score from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline to week 35 among patients with SOLO-CONTINUE baseline score ≤7, No./total No. (%) | 56/80 (70.0) | 45/81 (55.6) | 41/83 (49.4)c | 57/168 (33.9)a |

| Other secondary end pointsd | ||||

| Percent change in EASI scores from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, LS mean (SE) | −6.61 (0.80) | −1.75 (0.74)a | −1.37 (0.74)a | −0.09 (0.51)a |

| Patients with EASI-50 at week 36 among patients with EASI-50 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, No./total No. (%) | 33/83 (39.8) | 46/84 (54.8) | 52/86 (60.5)c | 124/169 (73.4)a |

| Percent change in Peak Pruritus NRS score from SOLO baseline: difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 35, LS mean (SE) | −35.6 (4.3) | −16.7 (4.1)a | −8.6 (4.0)a | 0.1 (3.1)a |

| Time to first event of IGA score ≥2 among patients with IGA score of 0 or 1 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline | ||||

| No. of patients with an event | 60 | 52 | 50 | 85 |

| No. of patients censored | 3 | 12 | 16 | 41 |

| No. of days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 76.0 (62.02) | 112.2 (85.98) | 105.0 (89.14) | 139.7 (99.95) |

| Median (95% CI) | 57 (56-58) | 85 (59-113) | 80 (55-85) | 114 (85-169) |

| Hazard ratio vs placebo (95% CI) | NA | 0.63 (0.43 to 0.92) | 0.71 (0.49 to 1.05) | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.64) |

| Patients with IGA scores increased to 3 or 4 at week 36 among patients with IGA score of 0 or 1 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, No./total No. (%) | 42/63 (66.7) | 31/64 (48.4)e | 23/66 (34.8)a | 33/126 (26.2)a |

| Percent change in SCORAD from SOLO baseline: difference between SOLO-CONTINUE baseline and week 36, LS mean (SE) | −28.97 (3.68) | −10.42 (2.99)a | −2.21 (2.74)a | −0.33 (2.09)a |

| Percent BSA affected: change from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, LS mean (SE) | −9.16 (1.64) | −2.74 (1.53)f | −1.74 (1.46)a | 1.27 (1.04)a |

| Change from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, LS mean (SE) | ||||

| POEM | −7.0 (0.90) | −2.8 (0.78)a | −0.8 (0.73)a | 0.3 (0.56)a |

| DLQI | −3.1 (0.52) | −1.5 (0.46)c | −0.3 (0.48)a | 0.2 (0.33)a |

| HADS | −0.8 (0.60) | −0.7 (0.52) | −0.2 (0.54) | 0.8 (0.39)c |

| Annualized event rate of flares from SOLO-CONTINUE baseline through week 36g,h | ||||

| Total No. of flares | 62 | 46 | 38 | 36 |

| Total patient-years followed | 54.7 | 56.9 | 58.2 | 112.1 |

| Adjusted annualized rate (95% CI) | 0.75 (0.47-1.21) | 0.59 (0.36-0.96) | 0.44 (0.26-0.73) | 0.21 (0.13-0.35) |

| Relative risk vs placebo (95% CI) | NA | 0.78 (0.45 to 1.36) | 0.58 (0.33 to 1.03) | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.49)a |

| Well-controlled weeks before rescue medication use, mean (SD), %i | 40.9 (30.35) | 53.2 (32.95) | 53.3 (35.86) | 63.0 (32.36) |

| Annualized event rate of skin infection treatment-emergent adverse events (excluding herpetic infections) through week 36 | ||||

| Total No. of events | 10 | 7 | 1 | 4 |

| Total patient-years of follow up | 54.7 | 56.9 | 58.2 | 112.1 |

| Adjusted annualized rate (95% CI) | 0.12 (0.04-0.33) | 0.09 (0.03-0.25) | 0.01 (0.001-0.097) | 0.02 (0.007-0.083) |

| Relative risk vs placebo (95% CI) | NA | 0.71 (0.23-2.23) | 0.10 (0.01-0.83)c | 0.20 (0.06-0.72)c |

| Post hoc end pointsd | ||||

| Percent change in EASI score from SOLO baseline to SOLO-CONTINUE week 36, subgroups by original dose regimen in SOLO, LS mean (SE) | ||||

| Originally taking dupilumab, 300 mg, every 2 wk | ||||

| No. | 39 | 39 | 41 | 80 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −72.73 (5.68) | −82.80 (4.12) | −85.35 (4.08) | −90.75 (2.96)j |

| Originally taking dupilumab, 300 mg, weekly | ||||

| No. | 44 | 45 | 45 | 89 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −69.32 (3.38) | −87.04 (3.24)a | −88.70 (3.00)a | −91.88 (2.13)a |

| Percent change in EASI score from SOLO baseline to SOLO-CONTINUE week 36, subgroups by SOLO-CONTINUE baseline IGA and EASI, LS mean (SE) | ||||

| Subgroup with IGA score >1 at week 36, among patients with IGA score of 0 or 1 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline | ||||

| No. | 53 | 36 | 32 | 50 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −63.7 (8.08) | −76.1 (9.14) | −76.3 (8.12) | −79.7 (7.60)c |

| Subgroup with <75% improvement in EASI score from SOLO baseline at week 36, among patients with EASI-75 at baseline | ||||

| No. | 34 | 14 | 19 | 17 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −43.9 (4.81) | −47.4 (6.96) | −57.8 (6.39)c | −58.6 (6.68)c |

| Patients who achieved EASI-90 at week 36 among patients with EASI-90 at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, No./total No. (%) | 10/55 (18.2) | 16/49 (32.7) | 33/56 (58.9)a | 75/116 (64.7)a |

| Percent change in Peak Pruritus NRS score from SOLO baseline to SOLO-CONTINUE week 35, subgroups by original dose regimen in SOLO (weekly or every 2 wk), LS mean (SE) | ||||

| Originally taking dupilumab, 300 mg, every 2 wk | ||||

| No. | 39 | 39 | 41 | 80 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −27.05 (7.57) | −50.93 (6.41)c | −51.61 (6.31)k | −60.91 (4.75)a |

| Originally taking dupilumab, 300 mg, weekly | ||||

| No. | 44 | 45 | 45 | 89 |

| LS mean (SE), % | −33.32 (7.29) | −38.68 (6.97) | −50.64 (7.14) | −59.59 (5.35)a |

| Patients with improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS score from SOLO baseline to SOLO-CONTINUE week 35, No./total No. (%) | ||||

| ≥4 Pointsl | 10/78 (12.8) | 21/79 (26.6)c | 27/82 (32.9)m | 78/159 (49.1)a |

| ≥3 Pointsn | 15/82 (18.3) | 28/82 (34.1)c | 34/84 (40.5)j | 95/166 (57.2)a |

| Patients who reported no sleep disturbance in the past 7 d at week 36 (POEM item 2), No. (%) | 18 (21.7) | 30 (35.7) | 41 (47.7)a | 103 (60.9)a |

| SCORAD Sleep Loss (scale, 0-10): change from SOLO baseline to SOLO-CONTINUE week 36, LS mean (SE) | −2.7 (0.3) | −3.3 (0.3) | −4.2 (0.2)a | −4.3 (0.2)a |

| Patients who reported no pain or discomfort, EQ-5D item, at week 36 among patients who reported moderate or severe pain or discomfort at SOLO baseline, No./total No. (%) | 13/63 (20.6) | 25/64 (39.1)c | 30/72 (41.7)c | 78/138 (56.5)a |

Abbreviations: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; EASI-50, proportion of patients with 50% or greater improvement in EASI from SOLO baseline; EASI-75, proportion of patients with 75% or greater improvement in EASI from SOLO baseline; EASI-90, proportion of patients with 90% or greater improvement in EASI from SOLO baseline; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimensional Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; SOLO-CONTINUE, Study to Confirm the Efficacy and Safety of Different Dupilumab Dose Regimens in Adults With Atopic Dermatitis; LS, least squares; NA, not applicable; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; SCORAD, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis.

P < .001 vs placebo.

P = .004 vs placebo.

P < .05 vs placebo.

P values are nominal for all endpoints other than coprimary or key secondary.

P = .009 vs placebo.

P = .002 vs placebo.

Safety analysis set: placebo, n = 82; dupilumab every 8 weeks, n = 84; dupilumab every 4 weeks, n = 87; dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, n = 167.

Flares were defined as worsening of disease requiring initiation or escalation of rescue treatment.

Defined as the proportion of patients who responded “yes” to the question: “Has your eczema been well-controlled over the last week?” and for whom no rescue treatment was administered during that week.

P ≤ .003 vs placebo.

P = .006 vs placebo.

Patients with Peak Pruritus NRS scores of 4 or greater at SOLO baseline.

P = .005 vs placebo.

Patients with Peak Pruritus NRS scores of 3 or greater at SOLO baseline.

Among patients with EASI-75 response at SOLO-CONTINUE baseline, significantly more dupilumab-treated patients maintained this response at week 36 vs patients receiving placebo (categorical coprimary end point) (Table 2 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). There was an apparent dose-dependent response: the proportion of patients with EASI-75 was higher with the weekly or every 2 weeks regimen (116 of 169 patients [71.6%]) than the every 4 weeks (49 of 86 patients [58.3%]; nominal P < .05) or every 8 weeks (45 of 84 patients [54.9%]; nominal P = .01) regimens (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Similar maintenance of improvement was seen for patients with 50% and 90% improvement in EASI scores (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the coprimary and key secondary outcomes (eTable 3 and eFigure 4 in Supplement 2).

Pruritus

Improvements in pruritus were maintained with dupilumab in a similar dose-dependent manner. Dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks resulted in Peak Pruritus NRS least squares mean improvement of 62.2% from SOLO baseline to SOLO week 16; by SOLO-CONTINUE week 35, improvement from SOLO baseline was 61.4% (eFigure 5 in Supplement 2). Fewer patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks (57 patients [33.9%]; P < .001) or every 4 weeks (41 patients [49.4%]; P = .01) had a 3-point or greater worsening in Peak Pruritus NRS at week 35 vs placebo (56 patients [70.0%]) (Table 2), with an apparently dose-dependent response (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Consistent with the continuous coprimary EASI end point, there was no overall loss of efficacy with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks (baseline vs week 35) in percentage change in Peak Pruritus NRS from SOLO baseline during SOLO-CONTINUE (0.1%; P < .001) (Table 2, Figure 2B, and eFigure 6 in Supplement 2), whereas there was a dose-dependent return of pruritus for the every 4 weeks (−8.6%; P < .001), every 8 weeks (−16.7%; P < .001), and placebo (−35.6%) groups, particularly after week 12 (Table 2, Figure 2B, and eFigure 6 in Supplement 2). Other Peak Pruritus NRS end points had similar findings (Table 2 and eFigure 5 and eFigure 7 in Supplement 2).

Other Clinical Efficacy End Points

For IGA end points, all dupilumab regimens sustained response significantly better than placebo (Table 2). For example, among patients who had IGA scores of 0 or 1 at baseline, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks (89 of 126 patients [70.6%]; P < .001), every 4 weeks (41 of 66 patients [62.1%]; P < .001), and every 8 weeks (32 of 64 patients [50.0%]; P = .01) maintained their IGA scores within 1 point of baseline at week 36 compared with placebo (18 of 63 patients [28.6%]). A similar pattern was observed for other IGA end points (Table 2). In post hoc analyses, higher proportions of patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks maintained their IGA scores within 1 point of baseline compared with dupilumab every 8 weeks, and more patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks maintained their IGA scores of 0 or 1 compared with patients receiving dupilumab every 8 weeks (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). For all other secondary efficacy end points, including flare rates and well-controlled weeks, dupilumab demonstrated significantly superior maintenance of efficacy vs placebo, with weekly or every 2 weeks administration consistently having greater improvement than administration every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks (Table 2 and eFigures 7, 8, 9, and 10 in Supplement 2).

Other Patient-Reported Symptoms

Dupilumab maintained response in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): differences (week 36 minus SOLO-CONTINUE baseline) showed further improvement from SOLO that was nominally significant for dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks vs placebo; for example, for POEM, dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks showed significant improvement (least squares mean change from baseline) of 0.3 vs −7.0 for placebo (P < .001); for DLQI, dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks showed improvement of 0.2 vs −3.1 for placebo (P < .001); and for HADS, dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks showed improvement of 0.8 vs −0.8 for placebo (P = .01). Dupilumab every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks showed some attrition of response for these parameters but remained nominally superior vs placebo for POEM and DLQI (Table 2 and Figure 2C-E). More dupilumab-treated patients vs patients receiving placebo reported no pain or discomfort at week 36; the proportion was greatest for administration weekly or every 2 weeks (dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, 78 of 138 patients [56.5%], P < .001; every 4 weeks, 30 of 72 patients [41.7%], P = .03; every 8 weeks, 25 of 64 patients [39.1%], P = .03; vs placebo, 13 of 63 patients [20.6%]) (Table 2). In addition, patients receiving treatment weekly or every 2 weeks were more likely to report no sleep disturbances at week 36; for example, among patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, 103 of 169 patients (60.9%; P < .001) achieved significant improvement in POEM item 2 compared with placebo (18 of 83 patients [21.7%]) and significant improvement in SCORAD sleep loss vs placebo (least squares mean [SE] change, −4.3 [0.2] for dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks vs −2.7 [0.3] for placebo; P < .001), with similar improvement seen among patients receiving dupilumab every 4 weeks vs placebo (Table 2).

Rescue Treatment

A higher cumulative percentage of placebo-treated patients used rescue treatment by week 36; patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had the lowest percentage of rescue medication use (33 of 169 patients [19.5%]) compared with placebo (40 of 83 patients [48.2%]) (Figure 2F). Patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had fewer days of rescue medication use (31.80 days per patient-year [post hoc end point]) than those receiving treatment every 4 weeks (57.97 days per patient-year), those receiving treatment every 8 weeks (51.37 days per patient-year), and those receiving placebo (73.12 days per patient-year). The most frequently used rescue medications were topical corticosteroids (from 30 of 169 patients [17.8%] for dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks to 37 of 83 patients [44.6%] for placebo). Few patients required systemic rescue treatment (mainly oral corticosteroids) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2), with greatest use among those receiving placebo (systemic corticosteroids: 6 of 83 patients [7.2%]; systemic immunosuppressants: 1 [1.2%]) and least among those receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks (systemic corticosteroids, 3 of 169 patients [1.8%]).

Additional Post Hoc Subgroup Analyses

To evaluate response among patients who did not achieve the stringent IGA 0 or 1 scores or EASI-75 end points in SOLO-CONTINUE, we conducted post hoc analyses of EASI in 2 subgroups: patients with IGA scores greater than 1 at week 36 (among those with IGA scores of 0 or 1 at baseline) and patients without EASI-75 at week 36 (among those with EASI-75 at baseline). In both subgroups, patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks or dupilumab every 4 weeks (EASI-75 subgroup only) but not every 8 weeks had nominally significantly greater improvements vs placebo in percentage change in EASI score from SOLO baseline to week 36. For example, in the IGA greater than 1 subgroup, least squares mean (SE) percentage change in EASI score was −79.7 (7.60) for the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks group vs −63.7 (8.08) for placebo (Table 2).

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 67 placebo-treated patients (81.7%) and 118 of 167 (70.7%) to 63 of 84 (75.0%) dupilumab-treated patients; the weekly or every 2 weeks group had the lowest rates (118 [70.7%]) (Table 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement 2). In all treatment groups, 14 of 420 patients (3.3%) reported treatment-emergent serious AEs (Table 3 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2). A total of 5 patients (1.2%) permanently discontinued study treatment because of treatment-emergent AEs (Table 3). Nasopharyngitis, injection-site reactions, herpes simplex virus infection, and headache were the most frequent treatment-emergent AEs, occurring at rates of 2% or higher in the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks group than in the placebo group; AD and skin infections were the most frequent treatment-emergent AEs, occurring at rates of 2% or higher in the placebo group than in the dupilumab groups (Table 3 and eTables 7, 8, and 9 in Supplement 2). Conjunctivitis incidences were low and similar across treatment groups (eg, 9 of 167 patients [5.4%] in the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks group and 4 of 82 patients [4.9%] in the placebo group) (Table 3 and eTable 10 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Adverse Events (Safety Analysis Set).

| Adverse Event | No. (%) of Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 82) | Dupilumab, 300 mg | |||

| Every 8 wk (n = 84) | Every 4 wk (n = 87) | Weekly or Every 2 wk (n = 167) | ||

| Overall TEAEs | ||||

| ≥1 | 67 (81.7) | 63 (75.0) | 64 (73.6) | 118 (70.7) |

| Leading to permanent study treatment discontinuation | 3 (3.7)a | 0 | 2 (2.3)b | 0 |

| Leading to temporary study treatment discontinuation | 10 (12.2) | 7 (8.3) | 7 (8.0) | 6 (3.6) |

| Deathc | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Treatment-emergent SAEd | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.6) | 6 (3.6) |

| MedDRA PT occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group | ||||

| Dermatitis atopic | 40 (48.8) | 27 (32.1) | 30 (34.5) | 34 (20.4) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 11 (13.4) | 11 (13.1) | 11 (12.6) | 32 (19.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (7.3) | 7 (8.3) | 5 (5.7) | 13 (7.8) |

| Headache | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.6) | 5 (5.7) | 8 (4.8) |

| Herpes simplex virus infectione | 0 | 4 (4.8) | 1 (1.1) | 7 (4.2) |

| Asthma | 3 (3.7) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (2.4) |

| Back pain | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (3.6) |

| Oral herpes infection | 3 (3.7) | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) |

| Influenza | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 5 (5.7) | 4 (2.4) |

| Bronchitis | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 5 (5.7) | 3 (1.8) |

| Urticaria | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (3.0) |

| Arthralgia | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 5 (3.0) |

| Pharyngitis | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.4) |

| Pruritus | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) |

| Sinusitis | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 6 (3.6) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Cough | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.4) |

| Insomnia | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 4 (2.4) |

| Nasal congestion | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.4) |

| Contact dermatitis | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Gastroenteritis | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 3 (1.8) |

| Ligament sprain | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Toothache | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Contusion | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Folliculitis | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Hordeolum | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 3 (3.4) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Proteinuria | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Rhinitis | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Seasonal allergy | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Tonsillitis | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Viral infection | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Colitis | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0 |

| Eye allergy | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0 |

| Ophthalmic herpes infection | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Fall | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Eye disorders with the PT conjunctivitisf | 4 (4.9) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.6) | 9 (5.4) |

| Nonherpetic skin infectionsg | 8 (9.8) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.4) |

| Injection-site reactionsh | 7 (8.5) | 6 (7.1) | 6 (6.9) | 18 (10.8) |

Abbreviations: MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; PT, MedDRA preferred term; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Two patients discontinued participation in the study because of atopic dermatitis and 1 patient because of acquired dacryostenosis.

One patient discontinued participation in the study because of glioblastoma, disorientation, and brain edema and 1 patient because of atopic dermatitis.

One death occurred during the 36-week treatment period (on study day 187) in a 21-year-old man in the dupilumab every 4 weeks group because of a gunshot wound (homicide). The event was considered by the investigator to be not related to study drug use.

The only SAE (MedDRA PT and system organ class) with incidence of 2% or greater in a treatment group was basal cell carcinoma, which occurred in 2 patients in the dupilumab every 8 weeks group and no other treatment groups.

Herpes simplex cutaneous infections with nonoral locations.

Includes any PTs that included the term conjunctivitis: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis bacterial, conjunctivitis viral, conjunctivitis allergic, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (for all conjunctivitis MedDRA PTs, see eTable 10 in Supplement 2).

Adjudicated; includes the following MedDRA PTs: tinea versicolor, folliculitis, impetigo, skin bacterial infection, skin infection, abscess limb, localized infection, staphylococcal skin infection, subcutaneous abscess, and tinea cruris (eTable 8 in Supplement 2).

MedDRA high-level terms (see eTable 7 in Supplement 2 for MedDRA PTs).

Trough Dupilumab Concentrations

Patients who continued to take dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks through week 36 maintained steady state serum concentrations of dupilumab consistent with SOLO-CONTINUE baseline concentrations, whereas the every 4 weeks group had 4- to 9-fold lower concentrations and the every 8 weeks group had 30- to 56-fold lower concentrations (eFigure 11 in Supplement 2). This finding was consistent with the known pharmacokinetic profile for dupilumab.25 For patients rerandomized to placebo from dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, median dupilumab concentrations decreased below the lower limit of quantification (0.078 mg/L) by SOLO-CONTINUE weeks 24 or 12, respectively.

Antidrug Antibodies

Treatment-emergent ADAs during SOLO-CONTINUE occurred in 9 of 80 individuals (11.3%) in the placebo group, 9 of 77 (11.7%) in the dupilumab every 8 weeks group, 5 of 83 (6.0%) in the dupilumab every 4 weeks group, 3 of 70 (4.3%) in the dupilumab every 2 weeks group, and 1 of 83 (1.2%) in the dupilumab weekly group, indicating a higher incidence of immunogenicity with less frequent dosage intervals. Because most treatment-emergent ADAs were low titer (<1000), there was no apparent effect of treatment-emergent ADAs on dupilumab exposure. No high treatment-emergent ADA titers (>10 000) were observed in SOLO-CONTINUE. Few patients (placebo, n = 2; dupilumab every 8 weeks, n = 1) had moderate titer (range, 1000-10 000) responses. Beyond what could be accounted for as differences attributable to dose regimen, there were no apparent clinical consequences on efficacy or safety associated with treatment-emergent ADAs in the relatively small number of dupilumab-treated patients in SOLO-CONTINUE.

Discussion

All dupilumab dose regimens were generally superior to placebo after 36 weeks of treatment in SOLO-CONTINUE. Continuing treatment with dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks from SOLO14 resulted in consistently greater maintenance of response—numerically better than dupilumab every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks (nominally significant for some end points) and significantly better than placebo for all end points—across multiple clinical end points and patient-reported outcomes (ie, pruritus, symptoms of AD, sleep, pain or discomfort, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression). For some continuous end points (eg, change in POEM, DLQI, and HADS scores), the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks groups had further improvement above levels achieved in SOLO. The less frequent dupilumab dose regimens had some dose-dependent reduction in efficacy. By contrast, some binomial responder end points (eg, EASI-75) had apparent attrition between baseline and week 36 for all treatment groups. Such attrition is inherent to this type of study, reflecting combined effects of several factors, including the fluctuating nature of response arising from the relapsing-remitting nature of AD; intrinsic variability of the scoring instruments; the SOLO-CONTINUE trial design, which started with 100% responders (ie, responder rates can only decrease); the nature of categorical scales, which are typically less sensitive than continuous scales; and the conservative nonresponder imputation methods used to account for rescue and missing data for categorical end points. Thus, both continuous and categorical end points are needed to provide an accurate, complete picture of response maintenance and to discern differences among treatment groups.

Overall, in dupilumab AD clinical trials, the most notable treatment-emergent AEs attributable to dupilumab were injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis.14,15,16,19,20 SOLO-CONTINUE found no new safety signals. Overall treatment-emergent AE incidence was higher with placebo than with dupilumab. Consistent with previous studies,14,15,16,19,20 skin infections and AD exacerbations were more frequent with placebo than with dupilumab. The patients receiving less frequent dupilumab doses, particularly every 8 weeks, had greater rates of skin infections, flares, and rescue medication use than patients receiving dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks. Unlike previous studies,14,15,16,19,20 conjunctivitis incidences were low (<6%) across all treatment groups. One possible reason is that SOLO-CONTINUE patients were all high-level responders, who in general tend to have conjunctivitis less frequently.26,27 In an in-depth analysis of conjunctivitis in multiple randomized clinical trials of dupilumab in AD, lower baseline AD severity and higher levels of response were associated with lower risk of conjunctivitis.28 In SOLO-CONTINUE, there were numerical imbalances that favored placebo for herpes simplex infections and serious AEs in this relatively small study, but this finding is not consistent with the larger overall experience in dupilumab phase 3 trials, wherein the number of serious AEs was lower with dupilumab and the number of clinically important herpetic infections (eczema herpeticum and herpes zoster) was also lower for dupilumab vs placebo.14,20,29

Despite the waxing-and-waning nature of AD symptoms, continued treatment with dupilumab using the more frequent treatment regimens (weekly or every 2 weeks) ensured the most consistent maintenance of treatment effect that is significantly better than placebo (and at least numerically better than every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks) across all end points throughout the trial. In post hoc comparisons (eFigure 2B in Supplement 2), dupilumab weekly did not appear to maintain clinical response better than dupilumab every 2 weeks. Because the dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks group had the highest maintenance of clinical response and every 2 weeks is the approved dose, every 2 weeks is recommended for long-term treatment. These findings also indicate that dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks for 16 weeks is generally insufficient for achievement of stable remission after cessation of dupilumab therapy, as demonstrated by patients who received dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks in SOLO and then received placebo during SOLO-CONTINUE; these patients experienced significant diminution in efficacy during the 36-week SOLO-CONTINUE trial vs those treated with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks throughout SOLO and SOLO-CONTINUE. Similar findings have also been reported for long-term biologic treatment of psoriasis.30 Of importance, on the basis of our findings that dupilumab (and thereby IL-4 and IL-13 blockade) can be beneficial in treating other type 2 inflammatory diseases (eg, asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis),6,7,8,9,10,11,12 whether continuous treatment is also required to maintain benefit in these settings should be evaluated. Most of these studies6,7,8,9,10,11 involved patients with advanced and/or chronic disease; it is worth considering whether treatment of earlier-stage disease with IL-4 and IL-13 blockers such as dupilumab may result in long-term rebalancing of the immune system and termination or possible reversal of the atopic march (ie, the progressive development of additional type 2 inflammatory conditions, such as asthma and/or allergic rhinitis, that often follows development of AD in children).13,31

In general, treatment-emergent ADA incidence inversely correlates with dose and treatment interval, consistent with other biologics.21,22,23 In SOLO-CONTINUE, treatment-emergent ADA incidences were lowest with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks and were slightly higher with less frequent treatment regimens. Because administration every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks did not provide an additional safety advantage and was numerically outperformed by administration weekly or every 2 weeks, we believe that it is prudent to adhere to the approved every 2 weeks regimen for adults and avoid less frequent treatment regimens (every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks) for long-term maintenance of efficacy.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is that the SOLO-CONTINUE population was restricted to SOLO patients who achieved stringently defined responses (IGA scores of 0 or 1 or EASI-75). Therefore, caution should be taken when interpreting the results of this study in the context of the overall population of dupilumab-treated patients with AD. Because of the high disease burden in patients enrolled in SOLO, neither an IGA score of 0 or 1 nor EASI-75 captures the full extent of clinically meaningful responses. A 50% improvement in EASI scores, for example, may represent a more relevant treatment outcome in this population of patients with moderate to severe AD: with a median baseline EASI score of approximately 30 in SOLO, 50% improvement represents more than twice the minimal clinically important difference of 6.6 or greater in individuals.14,32

Conclusions

In SOLO-CONTINUE, monotherapy with dupilumab, 300 mg, weekly or every 2 weeks for 36 weeks maintained the clinical efficacy achieved in SOLO and was significantly better than placebo across all outcomes. Less frequent administration (every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks) resulted in reduced efficacy, no safety advantages, and numerically higher treatment-emergent ADA incidences, whereas weekly administration had no apparent benefit over administration every 2 weeks. The approved every 2 weeks treatment regimen is the lowest-dosage regimen associated with consistent maintenance of clinical response in this trial and is therefore recommended for long-term treatment. However, therapeutic decisions are often influenced by cost-benefit considerations, in which case health care practitioners and other stakeholders involved in these decisions should carefully balance potential savings against suboptimal efficacy and long-term risks associated with discontinuous treatment paradigms. This study supports the use of 300 mg of dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks as effective regimens in adults with moderate to severe AD for long-term maintenance of treatment response.

Study Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Atopic/Allergic Comorbidities at SOLO Baseline (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 2. P values (Nominal) From Post Hoc Analysis of Comparisons Between Dupilumab High- and Low-Dose Regimens for Co-Primary and Key Secondary Endpoints

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses of Co-Primary Endpoints

eTable 4. Rescue Medication Use (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Patients With ≥1 Adverse Event per 100 Patient-years During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Treatment-Emergent Serious Adverse Events During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 7. Injection-Site Reactions During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 8. Skin Infections (Excluding Herpetic Skin Infections) During the 36-Week Treatment Period

eTable 9. Herpes Viral Infections During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set) (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 10. Conjunctivitisa During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percent Change in Improvement in EASI From SOLO Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study

eFigure 3. Percentage of Patients With EASI-75 at Week 36, Among Patients With EASI-75 at SOLO-CONTINUE Baseline (Co-Primary Endpoint)

eFigure 4. Percent Change (Improvement) in EASI From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study: Difference Between Solo-Continue Baseline and Week 36 — Primary and Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 5. Percent Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study in Patients Originally Treated in SOLO 1 or SOLO 2 (MI Analysis)

eFigure 6. Percent Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study: Difference Between SOLO-CONTINUE Baseline and Week 35

eFigure 7. Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Baseline Through Week 35 During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study

eFigure 8. Change (Improvement) in EASI From Baseline of the SOLO-CONTINUE Study Through Week 36 eFigure 9. Change (Improvement) in SCORAD From Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study Through Week 36

eFigure 10. BSA Affected by AD

eFigure 11. Log-Scaled Mean Functional Dupilumab Concentrations (+ SD) Over Time

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):633-643. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1109-1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1483-1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(14):5147-5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(14):5153-5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupilumab [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2019.

- 7.Dupilumab: Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. Published 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.

- 8.Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting β2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):31-44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2486-2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2475-2485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio RM, et al. Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(5):469-479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirano I, Dellon ES, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab efficacy in adults with active eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425-437. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. ; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators . Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335-2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130-139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):40-52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Worm M, et al. Dupilumab therapy provides clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs): a phase IIb, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):506-515. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsianakas A, Luger TA, Radin A. Dupilumab treatment improves quality of life in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(2):406-414. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083-1101. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287-2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brezinski EA, Armstrong AW. Off-label biologic regimens in psoriasis: a systematic review of efficacy and safety of dose escalation, reduction, and interrupted biologic therapy. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e33486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu L, Armstrong AW. Anti-drug antibodies in psoriasis: a critical evaluation of clinical significance and impact on treatment response. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9(10):949-958. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2013.836060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552-1563. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovalenko P, DiCioccio AT, Davis JD, et al. Exploratory population PK analysis of dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-4Rα, in atopic dermatitis patients and normal volunteers. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2016;5(11):617-624. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchio E, Miyakawa K, Ikezawa Z, Ohno S. Systemic and local immunological features of atopic dermatitis patients with ocular complications. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(1):82-87. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.1.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, Gislason GH, Skov L, Egeberg A. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):280-286.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(3):459-473. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Beck LA, et al. Infections in dupilumab clinical trials in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive pooled analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(3):443-456. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00445-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dávila-Seijo P, Dauden E, Carretero G, et al. ; BIOBADADERM Study Group . Survival of classic and biological systemic drugs in psoriasis: results of the BIOBADADERM registry and critical analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):1942-1950. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paller AS, Spergel JM, Mina-Osorio P, Irvine AD. The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: Many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MMG, Lindeboom R, Bos JD, Schmitt J. EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67(1):99-106. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02719.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Atopic/Allergic Comorbidities at SOLO Baseline (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 2. P values (Nominal) From Post Hoc Analysis of Comparisons Between Dupilumab High- and Low-Dose Regimens for Co-Primary and Key Secondary Endpoints

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses of Co-Primary Endpoints

eTable 4. Rescue Medication Use (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Patients With ≥1 Adverse Event per 100 Patient-years During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Treatment-Emergent Serious Adverse Events During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 7. Injection-Site Reactions During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 8. Skin Infections (Excluding Herpetic Skin Infections) During the 36-Week Treatment Period

eTable 9. Herpes Viral Infections During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set) (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 10. Conjunctivitisa During the 36-Week Treatment Period (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percent Change in Improvement in EASI From SOLO Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study

eFigure 3. Percentage of Patients With EASI-75 at Week 36, Among Patients With EASI-75 at SOLO-CONTINUE Baseline (Co-Primary Endpoint)

eFigure 4. Percent Change (Improvement) in EASI From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study: Difference Between Solo-Continue Baseline and Week 36 — Primary and Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 5. Percent Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study in Patients Originally Treated in SOLO 1 or SOLO 2 (MI Analysis)

eFigure 6. Percent Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Parent Study Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study: Difference Between SOLO-CONTINUE Baseline and Week 35

eFigure 7. Change (Improvement) in Peak Pruritus NRS From Baseline Through Week 35 During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study

eFigure 8. Change (Improvement) in EASI From Baseline of the SOLO-CONTINUE Study Through Week 36 eFigure 9. Change (Improvement) in SCORAD From Baseline During the SOLO-CONTINUE Study Through Week 36

eFigure 10. BSA Affected by AD

eFigure 11. Log-Scaled Mean Functional Dupilumab Concentrations (+ SD) Over Time

Data Sharing Statement