This cohort study assesses the directionality of the association between gray matter development and frequency of alcohol intoxication in European adolescents by performing causal bayesian network, temporality, and exposure-response curve analyses.

Key Points

Question

What is the directionality of the association between the increased frequency of drunkenness and gray matter development during adolescence?

Findings

In this cohort study of 726 adolescents enrolled in the IMAGEN European cohort, the 3 complementary approaches used (causal bayesian networks, temporality analyses, and exploration of exposure-response curves) suggested that accelerated gray matter atrophy in the frontal and posterior temporal cortices was associated with an increased risk for drunkenness.

Meaning

Findings from this study suggest that the neurotoxicity interpretation of the drinking-related acceleration of gray matter atrophy should be applied with caution.

Abstract

Importance

Alcohol abuse correlates with gray matter development in adolescents, but the directionality of this association remains unknown.

Objective

To investigate the directionality of the association between gray matter development and increase in frequency of drunkenness among adolescents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study analyzed participants of IMAGEN, a multicenter brain imaging study of healthy adolescents in 8 European sites in Germany (Mannheim, Dresden, Berlin, and Hamburg), the United Kingdom (London and Nottingham), Ireland (Dublin), and France (Paris). Data from the second follow-up used in the present study were acquired from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2016, and these data were analyzed from January 1, 2016, to March 31, 2018. Analyses were controlled for sex, site, socioeconomic status, family history of alcohol dependency, puberty score, negative life events, personality, cognition, and polygenic risk scores. Personality and frequency of drunkenness were assessed at age 14 years (baseline), 16 years (first follow-up), and 19 years (second follow-up). Structural brain imaging scans were acquired at baseline and second follow-up time points.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Increases in drunkenness frequency were measured by latent growth modeling, a voxelwise hierarchical linear model was used to observe gray matter volume, and tensor-based morphometry was used for gray matter development. The hypotheses were formulated before the data analyses.

Results

A total of 726 adolescents (mean [SD] age at baseline, 14.4 [0.38] years; 418 [58%] female) were included. The increase in drunkenness frequency was associated with accelerated gray matter atrophy in the left posterior temporal cortex (peak: t1,710 = –5.8; familywise error (FWE)–corrected P = 7.2 × 10−5; cluster: 6297 voxels; P = 2.7 × 10−5), right posterior temporal cortex (cluster: 2070 voxels; FWE-corrected P = .01), and left prefrontal cortex (peak: t1,710 = –5.2; FWE-corrected P = 2 × 10−3; cluster: 10 624 voxels; P = 1.9 × 10−7). According to causal bayesian network analyses, 73% of the networks showed directionality from gray matter development to drunkenness increase as confirmed by accelerated gray matter atrophy in late bingers compared with sober controls (n = 20 vs 60; β = 1.25; 95% CI, −2.15 to −0.46; t1,70 = 0.3; P = .004), the association of drunkenness increase with gray matter volume at age 14 years (β = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.01-0.46; t1,584 = 2; P = .04), the association between gray matter atrophy and alcohol drinking units (β = −0.0033; 95% CI, −6 × 10−3 to −5 × 10−4; t1,509 = −2.4; P = .02) and drunkenness frequency at age 23 years (β = −0.16; 95% CI, −0.28 to −0.03; t1,533 = −2.5; P = .01), and the linear exposure-response curve stratified by gray matter atrophy and not by increase in frequency of drunkenness.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that gray matter development and impulsivity were associated with increased frequency of drunkenness by sex. These results suggest that neurotoxicity-related gray matter atrophy should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Alcohol intoxication (ie, drunkenness) is frequent among adolescents and conveys greater risk for alcohol abuse.1 Although alcohol addiction has been associated with brain atrophy,2 heavy drinking in adolescents is also associated with reduced volume and thickness of frontal and temporal gray matter.3 Longitudinal structural brain studies found greater frontocortical and temporal cortex thinning in adolescents who did not drink alcohol at baseline but transitioned into alcohol abuse during follow-up4,5 compared with adolescents who drank no or low amounts of alcohol. However, this difference was absent when the groups were matched for age and when adolescents with no or low drinking were compared with those who transitioned into moderate drinking.6

During adolescence, the development of reward processing has been suggested to precede the development of cognitive control,7,8 thus promoting risky decision-making, including alcohol abuse.9 Moreover, the regions that are most sensitive to alcohol-related atrophy are also involved in brain networks engaged in response inhibition,10 decision-making,11,12 and alcohol-triggered emotions.13 Atrophy in anterior cingulate and in superior frontal and middle temporal gyri is a factor in alcohol abuse.14,15,16,17 Together, these observations suggest a role for brain developmental mechanisms in the onset of alcohol abuse.

Suggestions by previous studies that heavy drinking was associated with brain damage in adolescents were based on nonsignificant group difference at baseline and significant group difference after the onset of drinking.3,4,5,6 This exclusive reliance on time precedence ignores the dynamic nature of brain development that begins even before birth18 and might be associated with alcohol-related developmental trajectories that are established before the onset of drinking. Instead, causality may be inferred from observational studies using corroborative evidence, including but not restricted to temporality.19 Furthermore, studies did not report behavioral changes, such as in personality during adolescence, which are known to be factors in alcohol abuse.20

Thus, the directionality of the association between brain development and frequency of drunkenness remains unknown to date. Specifically, is alcohol abuse associated with changes in brain structure in adolescents and young adults, or is there a trajectory of brain development that is a contributing factor in behavior, which may put certain adolescents at greater risk of alcohol abuse?

In this cohort study, we adopted 3 complementary approaches to investigate the directionality of the association between gray matter development and the increase in drunkenness frequency. The first approach was causal bayesian network (CBN), which belongs to probabilistic reasoning and provides graphic representations of network conditional dependencies.21 Causal bayesian network addresses the questions of directionality, uncertainty, and complexity in a set of random, interrelated variables22 and is used in various fields.23,24,25 Reliable application of CBN requires a multidimensional assessment of interrelated features that possibly mediate the association between the brain and frequency of drunkenness, including sociodemographic status, genetics, cognition, behaviors, and personality. The second approach was temporality analyses in 3 different samples of alcohol consumers. The third approach was exploration of the exposure-response curves. The full procedure is detailed in the eMethods and eAppendix in the Supplement. The analyses workflow and participant flowchart are shown in eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement.

Methods

Participants

The present cohort study analyzed participants enrolled in IMAGEN, a prospective, multicenter brain imaging study.26 Healthy adolescents were recruited at age 14 years from schools around 8 sites in Germany (Mannheim, Dresden, Berlin, and Hamburg), the United Kingdom (London and Nottingham), Ireland (Dublin), and France (Paris). Data from the second follow-up used in the present study were acquired from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2016, and were analyzed from January 1, 2016, to March 31, 2018. Exclusion criteria are detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement. Participants’ alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco consumption and personality features were assessed at ages 14 years (baseline), 16 years (first follow-up), 19 years (second follow-up), and 23 years (third follow-up), thereby reducing the confounding factor of age. Structural brain imaging and cognitive measures were acquired at baseline and second follow-up. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of King’s College London, University of Nottingham, Trinity College Dublin, University of Heidelberg, Technische Universität Dresden, Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives, and University Medical Center at the University of Hamburg in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.27 The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Frequency of drunkenness was measured with the following question on the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs: How many times did you get drunk in the last 12 months (intoxicated from drinking alcoholic beverages, for example staggering when walking, not being able to speak properly, throwing up, or not remembering what happened)? The mean value of each response category was used for analyses (eg, a value of 3 on the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs referred to 3 to 5 episodes of drunkenness, yielding a score of 4). The increase in drunkenness frequency estimated by latent growth modeling was quantitative and normally distributed.

After the quality control procedure, 1938 (969 × 2) scans were preprocessed using the SPM-12b longitudinal pairwise tool (Functional Imaging Laboratory Methods Group). The midpoint within-participant templates were segmented with the VBM-8 toolbox (Christian Gaser, University of Jena) to avoid using adult tissue probability maps.28 A between-participant template was generated with the diffeomorphic anatomical registration through exponentiated lie (DARTEL) algebra.29 SPM-12b and SPM8-5236 (VBM8) were run on MATLAB, version 7.14.0 (The MathWorks Inc).

Confounding factors (socioeconomic status, puberty score, negative life events, and family history of alcohol dependency) were controlled for (eFigure 1 and eMethods in the Supplement). A polygenic risk score (PRS) for alcohol consumption30 was required to meet the CBN assumptions to reduce the risk of identifying a spurious direct link. Cognition (working memory, decision-making, and response inhibition) and behavior (delay discounting, passive avoidance learning, and personality) variables are detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement. Alcohol drinking units (at age 23 years) were acquired using the timeline follow-back method. Body mass index was not controlled for (eMethods in the Supplement). Missing values were imputed using multiple imputation.31

Statistical Analysis

Associations between quantitative variables were tested using hierarchical linear models, a 1-level random intercept for site and sex with lmerTest, version 3.1-0 (Per Bruun Brockhoff). All P values were Bonferroni corrected (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Increases in drunkenness frequency and in personality changes were estimated with latent growth modeling. Mplus (Muthén & Muthén) provided the slope (ie, the increase) and the intercept (ie, drunkenness frequency at age 14 years, given the frequency at each time point) for each participant. Missing values were estimated using maximum likelihood from all of the data available32 under the missing-completely-at-random assumption (Little MCAR test: χ21,290 = 286; P = .60).

Causal bayesian networks, following the Bayes theorem, modeled the posterior conditional probability of a consequence after observation of the distribution of the probability of new previous evidences in an iterative process. This approach is suited to modeling the directionality between variables acquired at the same time and to providing probabilistic dependencies in a directed acyclic graph.21 In addition, given a set of variables, CBN can be estimated in a data-driven approach. Each network corresponds to a goodness of fit to the observed data score (bayesian gaussian equivalent). The procedure of “hill climbing” adds, deletes, and reverses arcs in the current directed acyclic graph at a time until the bayesian gaussian equivalent no longer improves.33(p19-20)

We reported only the edges replicated in more than 90% of the 10 000 bootstrapped CBNs,33 and their directionality was the dominant direction (>50% of the bootstrapped CBNs24,33). Increases in drunkenness frequency between ages 14 and 19 years, drunkenness frequency at age 14 years, gray matter development between ages 14 and 19 years (first principal component), gray matter volume at age 14 years (first principal component of the same clusters), and PRS were considered. All CBN analyses used bnlearn.33

We considered individuals with minimal experiences with alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use until they were 16 years of age (117 had a maximum of 2 occasions of drinking alcohol in their lifetime16 from the initial sample of 726 participants). We compared gray matter development (first principal component) among the late drinkers (ie, for 20 participants, episodes of drunkenness occurred during mainly the last month before the scans at 19 years of age; for 60 participants in the sober control group, 0 lifetime drunkenness episodes occurred).

We tested whether gray matter volume among the 3 clusters (first principal component) at age 14 years was associated with increased drunkenness frequency after age 14 to 19 years in a selected subsample of participants without any episode of drunkenness the year before age 14 years (n = 604).

We tested whether gray matter atrophy (first principal component) was associated with frequency of drunkenness (n = 594) and alcohol drinking units at age 23 years (n = 532). We used the increase in binge drinking (ie, 5 drinks in a row) to control for previous alcohol intoxication.

We stratified effect sizes according to site by sex. We explored the exposure-response curves19 (n = 726) by ranking the strata according to increasing gray matter atrophy and increasing drunkenness frequency.

Results

In total, 2216 healthy adolescents were recruited into the IMAGEN cohort. The present study included 726 (33%) of these participants with good-quality data (Table 1; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Among the 726 participants, the mean (SD) age at baseline was 14.4 (0.38) years, 418 (58%) were female, and all were white. One hundred and two individuals (14%) had at least 1 drunkenness episode.

Table 1. Variables Description Within the Samplea .

| Variable | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 14.4 (0.38) [12.9 to 15.7] | 16.5 (0.56) [15 to 18.8] | 18.8 (0.6) [17.1 to 21.1] |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 418 (58) | ND | ND |

| Male | 308 (42) | ND | ND |

| Site proportion, No. (%) | |||

| London | 120 (17) | ND | ND |

| Nottingham | 138 (19) | ND | ND |

| Dublin | 48 (7) | ND | ND |

| Berlin | 72 (10) | ND | ND |

| Hamburg | 82 (11) | ND | ND |

| Mannheim | 92 (13) | ND | ND |

| Paris | 66 (9) | ND | ND |

| Dresden | 108 (15) | ND | ND |

| ESPAD | |||

| Frequency of drunkenness | 0.5 (1.8) [0 to 29.5] | 4.2 (8.7) [0 to 41] | 9.7 (12.5) [0 to 41] |

| Tobacco | 0.16 (1.4) [0 to 21] | 0.8 (2.7) [0 to 21] | 1.6 (4) [0 to 21] |

| Cannabis | 0.26 (2.4) [0 to 41] | 2.6 (8.3) [0 to 41] | 5.1 (11.7) [0 to 41] |

| LEQ | |||

| Negative life events | 6.4 (2.8) [0 to 16] | 5.9 (2.7) [0 to 17] | 3.6 (2.2) [0 to 14] |

| SURPS | |||

| Impulsivity | 2.4 (0.4) [1.4 to 4] | 2.2 (0.4) [1 to 3.4] | 2.1 (0.4) [1 to 3.4] |

| Sensation | 2.6 (0.5) [1 to 4] | 2.7 (0.5) [1.2 to 4] | 2.7 (0.5) [1 to 4] |

| Anxiety sensitivity | 2.3 (0.4) [1 to 3.8] | 2.3 (0.5) [1 to 4] | 2.4 (0.5) [1 to 4] |

| Negative thinking | 1.9 (0.4) [1 to 3.4] | 1.8 (0.4) [1 to 3.6] | 1.9 (0.4) [1 to 4] |

| NEO PI | |||

| Neuroticism | 23.13 (7.5) [4 to 45] | 22.57 (5.9) [1 to 44] | 20.8 (8.2) [1 to 47] |

| Extraversion | 29.7 (5.9) [10 to 45] | 29.2 (5.9) [10 to 45] | 29.4 (5.9) [11 to 45] |

| Openness | 26.7 (5.7) [11 to 45] | 27.7 (5.9) [8 to 48] | 28.9 (6.4) [12 to 45] |

| Agreeableness | 29.6 (5.1) [6 to 44] | 30.2 (5.3) [11 to 45] | 32.3 (5.5) [9 to 46] |

| Conscientiousness | 27.9 (6.6) [8 to 48] | 28.6 (7) [9 to 47] | 30.2 (7.2) [4 to 48] |

| CGT | |||

| Deliberation time, ms | 2245.55 (7194.52) [736.51 to 181 363.1] | ND | 1626.21 (699.30) [734.5 to 12 682.45] |

| Risk taking | 0.52 (0.14) [0.05 to 0.89] | ND | 0.52 (0.12) [0.13 to 0.86] |

| Delay aversion | 0.23 (0.14) [−0.7 to 0.77] | ND | 0.20 (0.15) [−0.13 to 0.83] |

| Quality of decision-making | 0.94 (0.08) [0.45 to 1] | ND | 0.96 (0.06) [0.55 to 1] |

| Overall bet | 0.48 (0.13) [0.05 to 0.83] | ND | 0.48 (0.11) [0.14 to 0.83] |

| Risk adjustment | 1.65 (0.96) [−0.6 to 4.6] | ND | 1.98 (0.95) [−0.3 to 4.78] |

| Pattern recognition memory, No. of correct trials | 95.3 (7.6) [41.7 to 100] | ND | 95.9 (7.1) [54 to 100] |

| Rapid visual processing | 0.9 (0.05) [0.7 to 1] | ND | 0.93 (0.04) [0 to 1] |

| Spatial working memory | |||

| Between errors | 18.6 (13) [0 to 63] | ND | 11.1 (12.2) [0 to 74] |

| Strategy | 31 (5.4) [18 to 43] | ND | 27.7 (6.2) [18 to 44] |

| Affective go or no-go mean correct latency, ms | |||

| Negative | 490 (111.8) [222 to 888] | ND | 513.3 (89.5) [215 to 964] |

| Positive | 473.5 (107.8) [196.9 to 828.9] | ND | 497.5 (87.8) [239 to 903] |

| Affective go or no-go total omissions, No. | |||

| Negative | 11.4 (7.9) [0 to 36] | ND | 6.2 (5.5) [0 to 36] |

| Positive | 13.3 (7.3) [0 to 36] | ND | 8 (5.4) [0 to 36] |

| Delay discounting κ value | 0.023 (0.03) [0 to 0.25] | ND | 0.024 (0.03) [0 to 0.24] |

Abbreviations: CGT, Cambridge Guessing Task (modified version of the Cambridge Gambling Task; CGT variables detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement); ESPAD, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; LEQ, Life Events Questionnaire; ND, no data acquired at the corresponding time point; NEO PI, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness Personality Inventory; SURPS, Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (this scale measured sensation seeking, impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and negative thinking).

All values given as mean (SD) [range] unless otherwise indicated.

Association With Site, Sex, Impulsivity, and Accelerated Gray Matter Atrophy

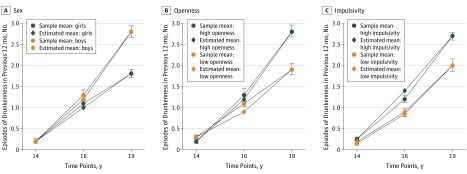

Drunkenness significantly increased over time (estimated SE = 8.1; P < .001) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Significant differences were found between sites (analysis of variance F7,718 = 12.4; P = 4.8 × 10−15), with higher increases in drunkenness frequency in England and Ireland (London, Nottingham, and Dublin) compared with the continental sites. The mean increase in drunkenness frequency was greater in male compared with female participants (0.52 vs 0.34; 95% CI, 12%-24%; t1,724 = 5.9; P = 3.6 × 10−9) (Figure 1A). Among possible personality,20 cognition,34 and behavioral35 confounding factors, only the increases in openness (β = 0.10; 95% CI, 0.05-0.16; t1,690 = 4; P = 2.4 × 10−3) and in impulsivity (β = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.57-1.9; t1,707 = 3.6; Bonferroni-corrected [25 models] P = 6.7 × 10−3) were associated with an increase in drunkenness frequency (Figure 1B and C; eTable 2 in the Supplement). Polygenic risk score was not associated with an increase in drunkenness frequency (β = 3209; 95% CI, −2769 to 9187; t1,699 = 1; P = .30).

Figure 1. Increase in Drunkenness Among 726 Participants.

Error bars are the SEM from the sample at each time point.

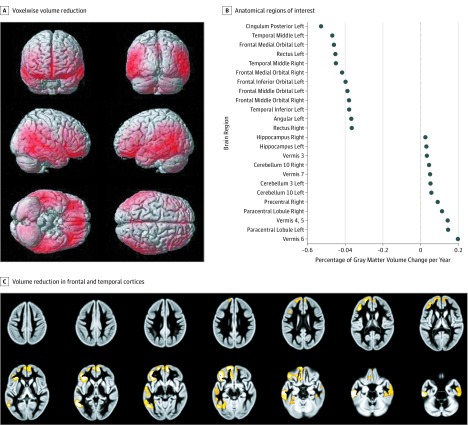

We found significant atrophy in the inferior frontal and temporal cortices independent of drunkenness (n = 907) (Figure 2A and B; eTables 7, 8, and 9 in the Supplement). An increase in drunkenness frequency was associated with accelerated gray matter atrophy in the left posterior temporal cortex (peak: t1,710 = –5.8; familywise error (FWE)–corrected P = 7.2 × 10−5; cluster: 6297 voxels; P = 2.7 × 10−5), in the right posterior temporal cortex (cluster: 2070 voxels; FWE-corrected P = .01), and in the left prefrontal cortex (peak: t1,710 = –5.2; FWE-corrected P = 2 × 10−3; cluster: 10 624 voxels; P = 1.9 × 10−7), extending to the left anterior insula and the anterior cingulate (Figure 2C and Table 2). These 3 clusters were also observed using a voxelwise hierarchical linear model (eFigure 4 and eTable 3 in the Supplement) and were confirmed with the increase of binge drinking (5 drinks in a row) and the first principal component of the 3 clusters (β = −0.76; 95% CI = −0.97 to −0.55; t1,701 = −7.1; P = 3.5 × 10−12) (eResults and eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Gray Matter Development Among Participants.

A, Cerebral regions show the voxelwise volume reduction. B, Percentage of gray matter volume change per year (from gray matter volume at age 14 years). The first 12 regions (on the left of the graph) show the most significant volume reduction (negative values), whereas the remaining 12 regions (on the right of the graph) show the most significant volume increase (positive values). C, The increase in frequency of drunkenness episodes between ages 14 and 19 years was the variable of interest. Confounding factors were site, sex, latent baseline drinking intercept factor, tobacco use, cannabis use,36 negative score on the Life Events Questionnaire,37 total intracranial volume difference, socioeconomic status, family history, and sex-centered puberty development score. Mass univariate voxelwise analyses were used.

Table 2. Clusters and Corresponding Features Associating Gray Matter Development and Increase in Frequency of Drunkenness (N = 726 Participants).

| Cluster | Cluster Size (Voxels) | AAL Structures | Peak Location MNI Coordinates | P Value for Cluster Level (FWE Corrected)a,b | t Value | Brodmann Area | P Value for Peak Level (FWE Corrected)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left prefrontal | 10 624 | Lateral frontal gyrus (L) | −42, 34, −12 | 1.9 × 10−7 | 5.2 | L BA 47 | 2 × 10−3 |

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | −44, 36, 0 | 4.96 | L BA 45 | 5 × 10−3 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (L) | −10, 34, −15 | 4.5 | L BA 11 | 4 × 10−2 | |||

| Left temporal | 6297 | Inferior temporal gyrus (L) + middle temporal gyrus (L) | −62, −21, −24 | 2.7 × 10−5 | 5.85 | BA 20 + BA 21 | 7.2 × 10−5 |

| Fusiform gyrus (L) | −52, −56, 0 | 5.26 | BA 37 | 1 × 10−3 | |||

| Right temporal | 2070 | Middle temporal gyrus (R) | 68, −26, −22 | 1 × 10−2 | NA | No voxels survived the FWE correction | NA |

Abbreviations: AAL, automatic anatomic label; BA, Brodmann area; FWE, familywise error; L, left; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; NA, not applicable; R, right.

All P values were FWE corrected.

P value at the peak level set at P = .001 uncorrected.

Directionality Analyses

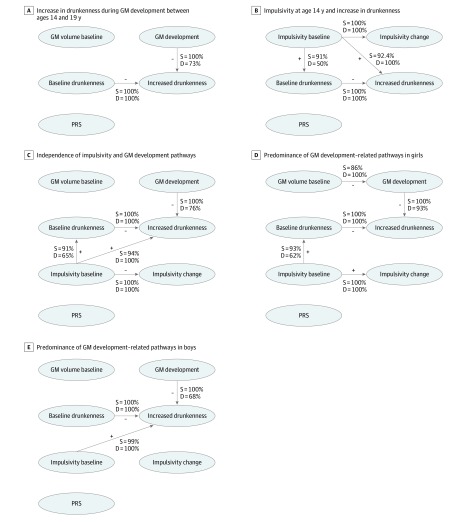

Bootstrapping revealed that 100% of the CBNs showed an association between gray matter atrophy and an increase in drunkenness frequency, of which 73% showed a direction from gray matter development to increased drunkenness frequency (Figure 3A). We found increased gray matter atrophy (between ages 14 and 19 years) in the late bingers compared with sober controls (n = 20 vs 60; β = 1.25; 95% CI, −2.15 to −0.46; t1,70 = 0.3; P = .004). Gray matter volume at age 14 years among nondrinkers was associated with a future increase in drunkenness frequency between ages 14 and 19 years (n = 604; β = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.01-0.46; t1,584 = 2; P = .04). Conversely, drunkenness frequency at age 14 years was not associated with gray matter development between ages 14 and 19 years in the whole sample (n = 726; β = 0.03; 95% CI, –0.09 to 0.14; t1,700 = 0.4; P = .60) or in the sample of alcohol drinkers at age 14 years (n = 122; β = −1 × 10−3; 95% CI, −0.22 to 0.22; t1,106 = –0.01; P > .99). Gray matter development was negatively associated with frequency of drunkenness (n = 594; β = –0.16; 95% CI, –0.28 to –0.03; t1,533 = –2.5; P = .01) and alcohol drinking units at age 23 years (n = 532; β = −0.0033; 95% CI, −6 × 10−3 to −5 × 10−4; t1,509 = −2.4; P = .02).

Figure 3. Causal Bayesian Networks .

Bayesian gaussian equivalent scores were −4610.7 (A), −4570.6 (B), −6407.7 (C), −3685.6 (D), and −2738.7 (E). The confounding factors (sex, site, puberty development score, negative life events, family history of alcoholism, and socioeconomic status) were modeled by regressing out their corresponding variance from each variable of interest (ie, node). Minus (–) or plus (+) sign indicates either negative or positive associations between the nodes; D indicates direction or proportion of networks (10 000 bootstraps) showing a direction from one node to another; GM, gray matter; PRS, polygenic risk score; and S, strength or the proportion of networks (10 000 bootstraps) with a statistically significant association.

Ranking the strata according to gray matter atrophy revealed a linear exposure-relation curve, whereas using the frequency of drunkenness to rank the groups did not (eFigures 5 and 6 in the Supplement). Individuals with the fastest gray matter atrophy (female participants from London) had a greater increase in drunkenness frequency compared with individuals with the slowest atrophy (male participants from Paris) (β = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11-0.45; t1,98 = 3.3; P = .001). Stratifying the sample by site and sex confirmed greater effect sizes in female participants and in Dresden (continent) (eTables 4 and 5 and eFigures 7 and 8 in the Supplement).

Impulsivity and Gray Matter Development as Independent Sex-Specific Pathways

We found no significant association between gray matter atrophy and increase in impulsivity (β = 0.7; 95% CI, −1.3 to 2.8; t1,707 = 0.7; P = .50). However, impulsivity at age 14 years correlated strongly with drunkenness frequency at age 14 years (β = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9; t1,712 = 4.1; P = 3.9 × 10−5) and increase in drunkenness frequency between ages 14 and 19 years (β = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.2-0.5; t1,708 = 5; P = 6.7 × 10−7), particularly among male participants (β = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; t1,293 = 5.4; P = 1 × 10−7) but not female participants (β = 0.1; 95% CI, −0.03 to 0.3; t1,405 = 1.5; P = .10). An increase in openness between ages 14 and 19 years was not associated with gray matter atrophy (β = −0.1; 95% CI, –0.3 to 0.06; t1,695 = –1.3; P = .20). Openness at age 14 years was not associated with drunkenness at this age (β = −0.005; 95% CI, –0.02 to 0.01; t1,613 = –0.7; P = .40) or with an increase in drunkenness between ages 14 and 19 years (β = 0.008; 95% CI, 0.001-0.01; t1,709 = 2.4; Bonferroni-corrected P = .07).

Post hoc CBN analyses tested for the directionality of the association between impulsivity and the increase in drunkenness frequency and PRS (5 variables). Impulsivity at age 14 years and increase in drunkenness frequency were associated with 92% of the networks, suggesting that impulsive behavior that was already established at age 14 years was associated with increased drunkenness frequency. Impulsivity and frequency of drunkenness at age 14 years were associated in 91% of the networks, but only 50% of the networks found directionality from impulsivity to drunkenness frequency at this age (Figure 3B).

A third CBN analysis evaluated whether the 2 pathways (ie, related to gray matter or impulsivity) were independent from each other (7 variables). We found stable directionality from gray matter development (76%) predominantly among female participants (93%) and from impulsivity at age 14 years to increase in drunkenness (94%) predominantly among male participants (99%) (Figure 3C-E). Constraining the directionality from the increase of drunkenness toward gray matter development yielded worse model fit indices (eTable 6 in the Supplement). These results remained when the imputed PRS missing values were used (eFigure 9 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Using complementary approaches to determine probable directionality, we found that the accelerated gray matter atrophy in frontal and temporal regions was associated with increased frequency of alcohol intoxication in adolescents. Although this brain development pathway was found in both sexes, it was more prominent in female participants. In male participants, we found a second and independent pathway in which increased impulsivity was associated with increased drunkenness frequency.

The finding that accelerated frontal atrophy was associated with frequency of drunkenness corroborates previous findings.4,6 However, Pfefferbaum et al6 did not find accelerated temporal atrophy, possibly owing to the cortex parcellation, which might have calculated a different pattern of temporal cortex development.35 Moreover, age had a limited confounding effect in our sample (eResults in the Supplement).

Temporal atrophy was greater during ages 14 to 19 years, whereas the age range of 12 to 21 years6 might have influenced temporal atrophy variance. For example, Squeglia et al34 found alcohol abuse–related accelerated atrophy in the temporal cortex using a similar approach as in the present study but with a younger sample at baseline. Results of the present study are consistent with those of a recent meta-analysis in substance dependency, which identified the shared pattern of gray matter atrophy (within the bilateral middle temporal gyrus, the left fusiform gyrus, and the right medial orbitofrontal cortex) across various substance use, suggesting that atrophy may underlie substance dependency in general rather than specific neurotoxicity.38 Prenatal exposure to alcohol has been suggested as a factor in gray matter development.39,40 However, we could not find any significant association between amount of alcohol intake during pregnancy and gray matter development (eResults in the Supplement).

Two important conditions for the successful application of CBN are controlling for potential confounding factors and verifying the results using long-term data.22,33 Unmeasured factors might confound the association between gray matter development and increase in drunkenness frequency. In the present study, we integrated various confounding factors, including demographic, behavioral, and genetic factors relevant to alcohol use. Thus, the comprehensive and multidomain assessment of possible confounding factors of increased drunkenness16 meets the assumptions for using CBN. Meanwhile, the longitudinal design of the study supports gray matter atrophy preceding the onset of drunkenness episodes in different temporal patterns of alcohol use. First, baseline gray matter volume was significantly associated with future frequency of drunkenness, corroborating previous results that gray matter development was associated with alcohol abuse.14,15,16,17,41 Second, late drinkers had accelerated atrophy. Although accelerated atrophy among late drinkers may not be induced by drunkenness within the last month before the assessment, we cannot formally rule out this possibility. Third, the cerebral pattern related to adolescent drunkenness is also associated with alcohol intake and drunkenness frequency at adulthood. This association remains significant, accounting for an increase in binge drinking that may indicate adult alcohol use42 and arguing for time precedence from gray matter development during adolescence to adult alcohol intake.

Plotting the effect sizes according to sex-by-site groups ranked by higher rate of gray matter atrophy revealed a linear trend of exposure-response curve, and the group with the fastest rate of gray matter atrophy had a greater increase in drunkenness frequency compared with the group with the slowest rate of gray matter atrophy. Conversely, ranking the groups according to drunkenness frequency did not provide the typical curve, suggesting that alcohol is toxic.43,44,45,46,47

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Causality can be proven only in randomized clinical trials, which are not feasible for ethical reasons. Therefore, compelling evidence from large, longitudinal, and well-characterized observational studies are the best evidence available according to the Hill criteria for inferring causality.19 The possible limitations of this approach are the unmeasured confounders that obscure true causality despite controlling for numerous intervening variables. Short of conducting a randomized clinical trial, we cannot rule out the possibility of the simultaneous occurrence of gray matter atrophy and increase in alcohol intoxication without any causation. For example, recent genetic epidemiologic investigations suggested that the presumed protective effect of moderate alcohol intake on stroke might be noncausal.48 Moreover, PRS score and the increase in drunkenness were not significantly associated, suggesting that the genetic contribution of drunkenness frequency during adolescence was not fully controlled for.

Although the temporal analyses were performed on 3 different patterns of alcohol consumption with the limited confounding factor of previous alcohol intake, the current design prevented the unambiguous determination that gray matter development occurred before the increase in drunkenness frequency. We believe that cohorts with multiple time points and individuals at high risk for alcohol dependency are needed to increase the proportion of heavy drinkers in future studies. Some CBNs can have equivalent classes, but the increase in drunkenness frequency is part of a V structure network, which renders their identification more robust (eAppendix in the Supplement).

We used voxel-based morphometry to obtain gray matter volume and tensor-based morphometry to obtain gray matter development. Although widely used, these frameworks provided different cerebral features, and strong conclusions require replication.

Conclusions

This study, which included a large, long-term, and well-characterized cohort of healthy adolescents in Europe, found that gray matter development and impulsivity were associated with increased frequency of drunkenness by sex. These findings add to the evidence suggesting a cerebral predisposition to alcohol abuse. We believe the results of this study call for a more cautious interpretation of neurotoxicity-related gray matter atrophy.

eMethods. Material and Methods

eResults

eAppendix. Causal Bayesian Networks: Simulated Data

eFigure 1. Analyses Workflow

eFigure 2. Participants’ Flowchart

eFigure 3. Drunkenness Episodes at Each Time Points

eFigure 4. Results from Voxel-Wise Analyses

eFigure 5. Forest Plot of Effect Size: Increasing Frequency of Drunkenness (and 95 Confidence Interval) of the Association Between the Increased Frequency of Drunkenness and Gray Matter Development (1st PC of the 3 clusters, TIV Diff regressed out), Stratified by Site (8 sites) and Gender

eFigure 6. Forest Plot of Effect Size: Increasing Rate of Gray Matter Atrophy (and 95 Confidence Interval) of the Association Between the Increased Frequency of Drunkenness and Gray Matter Development (1st PC of the 3 clusters, TIV Diff regressed out), Stratified by Site (8 sites) and Gender

eFigure 7. Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 Identified Clusters (1st principal component) and the Increase of Drunkenness By Site

eFigure 8. Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 Identified Clusters (1st principal component) and the Increase of Drunkenness By Gender

eFigure 9. Causal Bayesian Network Using Imputed PRS (n = 726)

eTable 1. Multiple Testing Correction

eTable 2. T and P values (Uncorrected) of Association Between Behavioral Variables and Drunkenness at Each Time Points Using Multilevel Modeling

eTable 3. Peak Location (MNI Space) and Cluster Size for Each Cluster According to the General Linear Model and the Hierarchical Linear Model

eTable 4. Estimates, 95 IC and P values Across Sites of the Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 identified Clusters (1st Principal Component) and the Increase of Drunkenness

eTable 5. Estimates, 95 IC and P values Across Gender of the Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 identified Clusters (1st Principal Component) and the Increase of Drunkenness

eTable 6. Bayesian Gaussian Equivalent (BGe) Scores for Each Model (n = 660) and Their Respective Modifications With the Arrow “From” Gray Matter Development “to” Increase of Drunkenness Reversed

eTable 7. 116 Automatic Anatomic Atlases (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b

eTable 8. 116 Automatic Anatomic Labeling (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development in Girls Only, Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b

eTable 9. 116 Automatic Anatomic Labeling (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development in Boys Only, Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b

References

- 1.DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):745-750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pluvinage R. Cerebral atrophy in alcoholics [in French]. Bull Mem Soc Med Hop Paris. 1954;70(15-16):524-526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfefferbaum A, Rohlfing T, Pohl KM, et al. Adolescent development of cortical and white matter structure in the NCANDA sample: role of sex, ethnicity, puberty, and alcohol drinking. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26(10):4101-4121. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squeglia LM, Tapert SF, Sullivan EV, et al. Brain development in heavy-drinking adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):531-542. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luciana M, Collins PF, Muetzel RL, Lim KO. Effects of alcohol use initiation on brain structure in typically developing adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(6):345-355. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.837057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfefferbaum A, Kwon D, Brumback T, et al. Altered brain developmental trajectories in adolescents after initiating drinking. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):370-380. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills KL, Goddings A-L, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore S-J. The developmental mismatch in structural brain maturation during adolescence. Dev Neurosci. 2014;36(3-4):147-160. doi: 10.1159/000362328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Achterberg M, Braams BR, Peters S, Crone EA. Testing a dual-systems model of adolescent brain development using resting-state connectivity analyses. Neuroimage. 2016;124(pt A):409-420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakemore S-J, Robbins TW. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(9):1184-1191. doi: 10.1038/nn.3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whelan R, Conrod PJ, Poline J-B, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Adolescent impulsivity phenotypes characterized by distinct brain networks. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(6):920-925. doi: 10.1038/nn.3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjork JM, Momenan R, Hommer DW. Delay discounting correlates with proportional lateral frontal cortex volumes. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(8):710-713. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray JC, Amlung MT, Owens M, et al. The neuroeconomics of tobacco demand: an initial investigation of the neural correlates of cigarette cost-benefit decision making in male smokers. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41930. doi: 10.1038/srep41930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, et al. Differential brain activity in alcoholics and social drinkers to alcohol cues: relationship to craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(2):393-402. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheetham A, Allen NB, Whittle S, Simmons J, Yücel M, Lubman DI. Volumetric differences in the anterior cingulate cortex prospectively predict alcohol-related problems in adolescence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(8):1731-1742. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3483-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squeglia LM, Ball TM, Jacobus J, et al. Neural predictors of initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(2):172-185. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15121587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whelan R, Watts R, Orr CA, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Neuropsychosocial profiles of current and future adolescent alcohol misusers. Nature. 2014;512(7513):185-189. doi: 10.1038/nature13402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheetham A, Allen NB, Whittle S, Simmons J, Yücel M, Lubman DI. Orbitofrontal cortex volume and effortful control as prospective risk factors for substance use disorder in adolescence. Eur Addict Res. 2017;23(1):37-44. doi: 10.1159/000452159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw P, Kabani NJ, Lerch JP, et al. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3586-3594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295-300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adan A, Navarro JF, Forero DA. Personality profile of binge drinking in university students is modulated by sex: a study using the Alternative Five Factor Model. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:120-125. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearl J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearl J. Causal inference in statistics: an overview. Stat Surv. 2009;3:96-146. doi: 10.1214/09-SS057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amstrup SC, Deweaver ET, Douglas DC, et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation can reduce sea-ice loss and increase polar bear persistence. Nature. 2010;468(7326):955-958. doi: 10.1038/nature09653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachs K, Perez O, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA, Nolan GP. Causal protein-signaling networks derived from multiparameter single-cell data. Science. 2005;308(5721):523-529. doi: 10.1126/science.1105809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuster-Parra P, Tauler P, Bennasar-Veny M, Ligęza A, López-González AA, Aguiló A. Bayesian network modeling: a case study of an epidemiologic system analysis of cardiovascular risk. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;126:128-142. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1128-1139. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajapakse JC, Giedd JN, DeCarli C, et al. A technique for single-channel MR brain tissue segmentation: application to a pediatric sample. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14(9):1053-1065. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(96)00113-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38(1):95-113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke T-K, Adams MJ, Davies G, et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and genetic overlap with other health-related traits in UK Biobank (N=112 117). Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(10):1376-1384. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scutari M. Learning Bayesian networks with the bnlearn R package. JSS. 2010;35(3):19-51. doi: 10.18637/jss.v035.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Nguyen-Louie TT, Tapert SF. Inhibition during early adolescence predicts alcohol and marijuana use by late adolescence. Neuropsychology. 2014;28(5):782-790. doi: 10.1037/neu0000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisdahl KM, Gilbart ER, Wright NE, Shollenbarger S. Dare to delay? the impacts of adolescent alcohol and marijuana use onset on cognition, brain structure, and function. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:53. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brumback T, Castro N, Jacobus J, Tapert S. Effects of marijuana use on brain structure and function: neuroimaging findings from a neurodevelopmental perspective. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2016;129:33-65. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paquola C, Bennett MR, Lagopoulos J. Understanding heterogeneity in grey matter research of adults with childhood maltreatment—a meta-analysis and review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:299-312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackey S, Allgaier N, Chaarani B, et al. ; ENIGMA Addiction Working Group . Mega-analysis of gray matter volume in substance dependence: general and substance-specific regional effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(2):119-128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17040415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckstrand KL, Ding Z, Dodge NC, et al. Persistent dose-dependent changes in brain structure in young adults with low-to-moderate alcohol exposure in utero. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(11):1892-1902. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01819.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meintjes EM, Narr KL, van der Kouwe AJW, et al. A tensor-based morphometry analysis of regional differences in brain volume in relation to prenatal alcohol exposure. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:152-160. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cservenka A, Gillespie AJ, Michael PG, Nagel BJ. Family history density of alcoholism relates to left nucleus accumbens volume in adolescent girls. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(1):47-56. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crosnoe R, Kendig S, Benner A. College-going and trajectories of drinking from adolescence into adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 2017;58(2):252-269. doi: 10.1177/0022146517693050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Alcohol consumption and risk of heart failure: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(4):367-373. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rota M, Bellocco R, Scotti L, et al. Random-effects meta-regression models for studying nonlinear dose-response relationship, with an application to alcohol and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Stat Med. 2010;29(26):2679-2687. doi: 10.1002/sim.4041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan D, Liu L, Xia Q, et al. Female alcohol consumption and fecundability: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13815. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14261-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VWV, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)—a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1411-1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03050.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GLG, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010;105(5):817-843. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millwood IY, Walters RG, Mei XW, et al. ; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group . Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: a prospective study of 500 000 men and women in China. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1831-1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31772-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Material and Methods

eResults

eAppendix. Causal Bayesian Networks: Simulated Data

eFigure 1. Analyses Workflow

eFigure 2. Participants’ Flowchart

eFigure 3. Drunkenness Episodes at Each Time Points

eFigure 4. Results from Voxel-Wise Analyses

eFigure 5. Forest Plot of Effect Size: Increasing Frequency of Drunkenness (and 95 Confidence Interval) of the Association Between the Increased Frequency of Drunkenness and Gray Matter Development (1st PC of the 3 clusters, TIV Diff regressed out), Stratified by Site (8 sites) and Gender

eFigure 6. Forest Plot of Effect Size: Increasing Rate of Gray Matter Atrophy (and 95 Confidence Interval) of the Association Between the Increased Frequency of Drunkenness and Gray Matter Development (1st PC of the 3 clusters, TIV Diff regressed out), Stratified by Site (8 sites) and Gender

eFigure 7. Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 Identified Clusters (1st principal component) and the Increase of Drunkenness By Site

eFigure 8. Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 Identified Clusters (1st principal component) and the Increase of Drunkenness By Gender

eFigure 9. Causal Bayesian Network Using Imputed PRS (n = 726)

eTable 1. Multiple Testing Correction

eTable 2. T and P values (Uncorrected) of Association Between Behavioral Variables and Drunkenness at Each Time Points Using Multilevel Modeling

eTable 3. Peak Location (MNI Space) and Cluster Size for Each Cluster According to the General Linear Model and the Hierarchical Linear Model

eTable 4. Estimates, 95 IC and P values Across Sites of the Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 identified Clusters (1st Principal Component) and the Increase of Drunkenness

eTable 5. Estimates, 95 IC and P values Across Gender of the Association Between the Gray Matter Development in the 3 identified Clusters (1st Principal Component) and the Increase of Drunkenness

eTable 6. Bayesian Gaussian Equivalent (BGe) Scores for Each Model (n = 660) and Their Respective Modifications With the Arrow “From” Gray Matter Development “to” Increase of Drunkenness Reversed

eTable 7. 116 Automatic Anatomic Atlases (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b

eTable 8. 116 Automatic Anatomic Labeling (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development in Girls Only, Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b

eTable 9. 116 Automatic Anatomic Labeling (AAL) Regions of Interest Mean Value of Gray Matter Development in Boys Only, Estimated by the Pairwise Longitudinal Processing of SPM12b