This cross-sectional study assesses the association between pediatric suicide rates and county-level poverty concentration in the United States from 2007 to 2016.

Key Points

Question

What is the association between pediatric suicide and county-level poverty in the United States?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 20 982 US youths aged 5 to 19 years who died by suicide from 2007 to 2016, the adjusted pediatric suicide rate increased with increasing county poverty concentration, defined as the percentage of the county population living below the federal poverty level.

Meaning

The findings suggest that higher county-level poverty concentration is associated with increased suicide rates among persons aged 5 to 19 years, which may have implications for suicide prevention efforts.

Abstract

Importance

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, with rates nearly doubling during the past decade. Youths in impoverished communities are at increased risk for negative health outcomes; however, the association between pediatric suicide and poverty is not well understood.

Objective

To assess the association between pediatric suicide rates and county-level poverty concentration.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, cross-sectional study examined suicides among US youths aged 5 to 19 years from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2016. Suicides were identified using International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File. Data analysis was performed from February 1, 2019, to September 10, 2019.

Exposures

County poverty concentration and the percentage of the population living below the federal poverty level. Counties were divided into 5 poverty concentration categories: 0% to 4.9%, 5.0% to 9.9%, 10.0% to 14.9%, 15.0% to 19.9%, and 20.0% or more of the population living below the federal poverty level.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study used a multivariable negative binomial regression model to analyze the association between pediatric suicide rates and county poverty concentration, reporting adjusted incidence rate ratios (aIRRs) with 95% CIs. The study controlled for year, demographic characteristics of the children who died (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), county urbanicity, and county demographic features (age, sex, and racial composition). Subgroup analyses were stratified by method.

Results

From 2007 to 2016, a total of 20 982 youths aged 5 to 19 years died by suicide (17 760 [84.6%] were aged 15-19 years, 15 982 [76.2%] male, and 14 387 [68.6%] white non-Hispanic). The annual suicide rate was 3.35 per 100 000 youths aged 5 to 19 years. In the multivariable model, compared with counties with the lowest poverty concentration (0%-4.9%), counties with poverty concentrations of 10% or greater had higher suicide rates in a stepwise manner (10.0%-14.9%: aIRR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.06-1.47]; 15.0%-19.9%: aIRR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.10-1.54]; and 20.0% or more: aIRR, 1.37 [95% CI, 1.15-1.64]). When stratified by method, firearm suicides had the strongest association with county poverty concentration (aIRR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.41-2.49) in counties with 20% or higher poverty concentration compared with counties with 0% to 4.9% poverty concentration.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that higher county-level poverty concentration is associated with increased suicide rates among youths aged 5 to 19 years. These findings may guide research into upstream risk factors associated with pediatric suicide to inform suicide prevention efforts.

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 3013 youths aged 5 to 19 years died by suicide in 2017, equivalent to 4.8 deaths per 100 000 youths. From 2007 to 2017, pediatric suicide rates increased 88%.1 Knowledge of the risk factors for pediatric suicide may guide targeted interventions because effective programs exist to reduce suicidal ideation and attempts.2

The association of poverty with suicide among youths is not well understood. Poverty has been associated with worse youth health outcomes, including higher rates of intentional and unintentional injuries.3,4 Youths experience poverty at the household and neighborhood levels, and each type of poverty may distinctly contribute to youth health outcomes.5 At the household level, receipt of public assistance in Sweden has been associated with a 2-fold higher risk of suicide among adolescents and young adults.6 Neighborhood poverty in Canada has been associated with youth suicidal thoughts and attempts, even after controlling for family socioeconomic status, but the study did not examine suicide deaths.7 Whether socioeconomic deprivation at the community level increases the risk of pediatric suicide has not been well studied.

Suicides have been found to cluster geographically, with mixed associations found between area socioeconomics and suicide rates.8 At the county level in the United States, high-risk areas for suicides in Ohio were associated with higher socioeconomic deprivation.9 In contrast, an analysis10 in Florida found the reverse, with areas at high risk for suicide associated with lower economic deprivation. These studies8,9,10 were not national samples and did not focus on the pediatric population. The objective of our study was to examine the association of pediatric suicide and county-level poverty concentration in the United States. We hypothesized that there would be higher suicide rates among youths living in counties with higher poverty concentrations.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study of suicides among US youths aged 5 to 19 years from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2016. We used mortality data from the CDC’s Compressed Mortality File (CMF), an administrative database composed of death certificate data maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics.11 Causes of death are classified according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), with county-level death counts reported annually.12 Our data use agreement with the National Center for Health Statistics prohibited efforts to determine case identities, which enabled full data set access without data suppression for low counts. From the US Census Bureau, we obtained annual intercensal county population estimates.13,14 We obtained county poverty measures from the US Census Bureau Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates Program.15 We obtained urbanicity measures from the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.16 Data analysis was performed from February 1, 2019, to September 10, 2019. Because the study included only fatalities, it did not meet the definition of human subjects research and was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval by Boston Children's Hospital.

Study Measures

The study outcome was suicide deaths among youths aged 5 to 19 years, as identified within the CMF by ICD-10-CM cause of death codes for intentional self-harm (suicide): U03, X60-X84, and Y87.0. The use of ICD-10-CM codes to identify causes of death has been previously described.17 Suicide methods were identified using the External Cause of Injury (E-code) mortality matrix, which reports mechanism of death and intent (eg, firearm, suicide) based on ICD-10-CM codes.17

Annual county poverty concentration, the percentage of the population living below the federal poverty level, was divided into 5 groups (0%-4.9%, 5.0%-9.9%, 10.0%-14.9%, 15.0%-19.9%, and ≥20%) based on previously published studies.4,18,19,20 The federal poverty level was $21 027 in annual household income for a family of 4 in 2007 and $24 339 in 2016.21

From the US census, we obtained annual county-level population estimates stratified by race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other race/ethnicity), age group (5-9, 10-14, and 15-19 years), and sex (male or female). Youths of other race/ethnicity combinations (including non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders, American Indians, and Alaska Natives) comprised only 9% of the population. In the CMF, 52 youths (0.2%) who died by suicide had unknown Hispanic ethnicity recorded on their death certificates, and these youths were analyzed in the other race/ethnicity category. We determined the annual percentage of youths in each county who were 10 to 14 years of age and 15 to 19 years age; the percentage who were non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic; and the percentage who were male as measures of youth demographic composition by county. Because rural location is a risk factor for pediatric suicide, we included measures of county urbanicity.22,23 Counties were classified into 9 groups using 2013 Rural Urban Continuum Codes, based on population size and adjacency to metropolitan areas.16

Statistical Analysis

We determined the frequencies of suicide deaths among US youths aged 5 to 19 years. We calculated annual suicide rates per 100 000 youths across strata of demographic variables (age, sex, and race/ethnicity) and by the 5 county poverty concentration categories. We determined the relative risk of suicide within each demographic category by calculating adjusted incidence rate ratios (aIRRs) with 95% CIs, using referent categories of age of 5 to 9 years, male sex, and white non-Hispanic race/ethnicity. We assessed for trends in suicide rates over time by estimating a Poisson regression with suicides as the outcome, year as the predictor, and total population as the offset. We determined frequencies of suicide by each method based on the E-code mortality matrix.

To analyze the association between pediatric suicide rates and county poverty concentration, we used a population-averaged generalized estimating equation. We constructed panels to account for clustering of data within counties across years. Each demographic group by race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other), age group (5-9, 10-14, and 15-19 years), and sex (male or female) within each county was considered a panel, which was then represented by 10 observations, with 1 for each year of the study (2007-2016). County poverty concentration, which could vary each year, was analyzed using the subgroups described above. We estimated a multivariable negative binomial regression model with suicide count as the outcome and county poverty concentration as the independent variable, controlling for year (modeled as a set of dummy variables with 2007 as the referent), county urbanicity, demographic characteristics of the youths who died by suicide (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), and county youth demographic composition. Models included the log of the stratum-specific population estimate as the offset (coefficient constrained to 1) to estimate incidence rates (in which strata are defined by county, year, age group, sex, and race/ethnicity). Thus, each stratum contributed a count of suicide decedents and a corresponding population estimate to the calculation of incidence rates. County poverty concentration was modeled with indicator variables with the lowest poverty concentration (0%-4.9%) as the referent.4,18,19 We calculated aIRRs with 95% CIs for each subsequent poverty concentration. Models used robust SE estimates and an unstructured within-group correlation structure. As a collinearity diagnostic metric, we calculated the variance inflation factor among the independent variables.

For secondary analyses, we decided a priori to select all suicide methods with a total count of 500 or more (ie, a mean of at least 50 incidents per year) during the study period. We did not assess less common methods because these may be underpowered to detect significant differences in suicide risk between poverty concentration categories. To determine the association between pediatric suicide by each method and county poverty concentration, we constructed regression models identical to the one described above, except we used the suicide count for each method as the dependent variable.

We performed exploratory analyses to assess whether the magnitude of the association of pediatric suicide with county poverty concentration was modified by the youth’s sex, age, or race/ethnicity. For these analyses, we added interaction terms between county poverty concentration and each of these demographic factors to the model. For instance, to assess whether the youth’s sex moderated the association between poverty and pediatric suicide, we added an interaction term between poverty concentration and sex. For age, because of convergence issues, a binary age category of 5 to 14 years vs 15 to 19 years was used. All analyses were performed with Stata software, version 13.0 (StataCorp).

Results

From 2007 to 2016, there were 20 982 suicides among youths aged 5 to 19 years (17 760 [84.6%] were 15-19 years of age, 15 982 [76.2%] male, and 14 387 [68.6%] white non-Hispanic) (Table 1). The annual national suicide rate for the study period was 3.35 per 100 000 youths aged 5 to 19 years. The suicide rate for male youths was more than 3 times greater than for female youths (IRR, 3.05; 95% CI, 2.76-3.38). Compared with white non-Hispanic youths, black non-Hispanic youths (IRR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.48-0.64) and Hispanic youths (IRR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.45-0.58) had lower suicide rates. The overall suicide rate increased from 2.66 per 100 000 youths in 2007 to 4.12 per 100 000 youths in 2016, with an increase of 4.6% annually (IRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.05). The 3 most common methods of suicide during the study period were suffocation (9631 [45.9%]), firearms (8619 [41.1%]), and poisoning (1282 [6.1%]) (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 1. Demographics of US Youths Aged 5 to 19 Years and Suicide Data, 2007 to 2016.

| Demographic | Youths, No. (%) | Annual Suicide Rate, Deaths per 100 000 Youths | Suicide IRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Populationa | Suicide During 2007-2016 | |||

| Youths aged 5-19 y | 62 575 817 | 20 982 | 3.35 | NA |

| Age, y | ||||

| 5-9 | 20 294 667 (32.4) | 57 (0.3) | 0.03 | 1 [Reference] |

| 10-14 | 20 683 561 (33.1) | 3165 (15.1) | 1.53 | 51.84 (24.55-142.33) |

| 15-19 | 21 597 589 (34.5) | 17 760 (84.6) | 8.22 | 278.14 (127.54-758.94) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 32 006 412 (51.1) | 15 982 (76.2) | 4.99 | 3.05 (2.76-3.38) |

| Female | 30 569 406 (48.9) | 5000 (23.8) | 1.64 | 1 [Reference] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 34 017 572 (54.4) | 14 387 (68.6) | 4.23 | 1 [Reference] |

| Black non-Hispanic | 8 888 897 (14.2) | 2093 (10.0) | 2.35 | 0.56 (0.48-0.64) |

| Hispanic | 14 062 735 (22.5) | 3043 (14.5) | 2.16 | 0.51 (0.45-0.58) |

| Other | 5 633 925 (9.0) | 1459 (7.0) | 2.59 | 0.61 (0.51-0.73) |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

Population is the mean population in each demographic subcategory (ie, age of 5-9 years) during the 2007 to 2016 study period.

The youth demographic composition varied by county poverty concentration, with a lower percentage of white non-Hispanic youth living in counties with higher poverty concentrations (Table 2). Counties with the lowest poverty concentration (0%-4.9%) had a suicide rate of 3.18 per 100 000 youths, and counties with the highest poverty concentration (≥20%) had a suicide rate of 3.35 per 100 000 youths (Table 3).

Table 2. Demographics of US Youths Aged 5 to 19 Years by County Poverty Concentration, 2007 to 2016.

| Demographic | Total | Poverty Concentration, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4.9 | 5.0-9.9 | 10.0-14.9 | 15.0-19.9 | ≥20.0 | ||

| US population aged 5-19 y, No. (%)a | 62 575 817 | 695 798 (1.1) | 11 728 729 (18.7) | 20 064 014 (32.1) | 20 975 447 (33.5) | 9 111 829 (14.6) |

| Youths, %b | ||||||

| Aged 5-9 y | 32.4 | 33.7 | 32.5 | 32.3 | 32.6 | 32.3 |

| Aged 10-14 y | 33.1 | 35.1 | 33.9 | 33.2 | 32.7 | 32.3 |

| Aged 15-19 y | 34.5 | 31.2 | 33.6 | 34.5 | 34.7 | 35.4 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 51.1 | 51.3 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 51.1 | 51 |

| Female | 48.9 | 48.7 | 48.7 | 48.8 | 48.9 | 49 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 54.4 | 73.9 | 65.3 | 61.2 | 47.3 | 40.1 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 14.2 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 10.6 | 16 | 25.2 |

| Hispanic | 22.5 | 10 | 14.4 | 19.1 | 28.5 | 27.5 |

| Other | 9 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 7.2 |

Population is the mean annual population living in each poverty concentration during the 2007 to 2016 study period.

Percentages reported are of the demographic subgroup (ie, age of 5-9 years) within each county poverty concentration.

Table 3. Annual Suicide Rates Across Individual Demographic Variables of Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and County Poverty Concentration, 2007 to 2016.

| Demographic | Total | Poverty Concentration, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4.9 | 5.0-9.9 | 10.0-14.9 | 15.0-19.9 | ≥20 | ||

| Suicides, No. (%) | 20 982 | 221 (1.1) | 3762 (17.9) | 7102 (33.8) | 6847 (32.6) | 3050 (14.5) |

| Annual suicide rate, deaths/100 000 youths | ||||||

| Overall | 3.35 | 3.18 | 3.21 | 3.54 | 3.26 | 3.35 |

| Aged 5-9 y | 0.03 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Aged 10-14 y | 1.53 | 1.15 | 1.29 | 1.58 | 1.55 | 1.72 |

| Aged 15-19 y | 8.22 | 8.9 | 8.22 | 8.71 | 7.91 | 7.83 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4.99 | 4.82 | 4.73 | 5.23 | 4.91 | 5.03 |

| Female | 1.64 | 1.45 | 1.61 | 1.77 | 1.55 | 1.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 4.23 | 3.67 | 3.78 | 4.38 | 4.41 | 4.26 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 2.35 | 2.08 | 2.33 | 2.55 | 2.46 | 2.04 |

| Hispanic | 2.16 | 1.87 | 2.17 | 2.13 | 2.12 | 2.32 |

| Other | 2.59 | 1.49 | 1.93 | 2.01 | 2.17 | 6.77 |

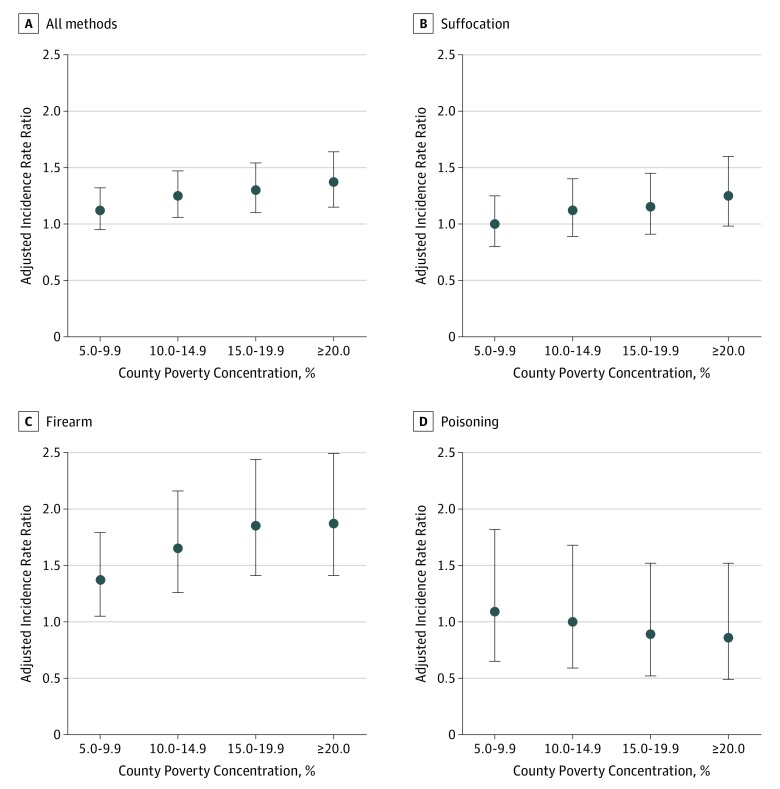

In the multivariable model, there was a higher suicide rate in the highest poverty concentration counties (≥20%; aIRR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.15-1.64) compared with the lowest poverty concentration counties (0%-4.9%), and suicide rates increased in a stepwise manner as poverty concentration increased (Figure and Table 4). In this model, male youths had a higher suicide rate than female youths (aIRR, 3.03; 95% CI, 2.92-3.15). Compared with younger youths (5-9 years of age), suicide rates were higher among youths 10 to 14 years of age (aIRR, 56.03; 95% CI, 41.89-74.96) and 15 to 19 years of age (aIRR, 300.05; 95% CI, 224.71-400.64). Compared with white non-Hispanic children, suicide rates were lower for black non-Hispanic children (aIRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.60-0.68), Hispanic children (aIRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.57-0.64), and children of other races/ethnicities (aIRR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.55-0.63). Suicide rates were higher in 2016 compared with 2007 (aIRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.43-1.64). The suicide rate was higher in the most rural counties compared with the most urban counties (aIRR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.45-1.91). There was no collinearity between the independent variables.

Figure. Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio of Suicides Among Youths Aged 5 to 19 Years by County Poverty Concentration and Method.

Models control for year, individual demographics, county urbanicity, and county youth demographic composition. Data are reported compared with the lowest poverty concentration (0%-4.9% of the county population living below the federal poverty level). Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Table 4. Relative Risk of Suicide Among Youths Aged 5 to 19 Years by County Poverty Concentration and Suicide Method, 2007-2016.

| Poverty Concentration, % | Suicide aIRR (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Methods | Suffocation | Firearm | Poisoning | |

| 0-4.9 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 5.0-9.9 | 1.12 (0.95-1.32) | 1.00 (0.80-1.25) | 1.37 (1.05-1.79) | 1.09 (0.65-1.82) |

| 10.0-14.9 | 1.25 (1.06-1.47) | 1.12 (0.89-1.40) | 1.65 (1.26-2.16) | 1.00 (0.59-1.68) |

| 15.0-19.9 | 1.30 (1.10-1.54) | 1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 1.85 (1.41-2.44) | 0.89 (0.52-1.52) |

| ≥20.0 | 1.37 (1.15-1.64) | 1.25 (0.98-1.60) | 1.87 (1.41-2.49) | 0.86 (0.49-1.52) |

Abbreviation: aIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio.

Models control for year, individual demographics, county urbanicity, and county youth demographic composition.

The association of county poverty concentration with pediatric suicide rates varied by suicide method. Three methods with a total suicide count of 500 or greater during the study period were selected for subanalysis: suffocation, firearms, and poisoning (Table 4). Among firearm suicides, the suicide rate increased in a stepwise manner with increasing poverty concentration compared with the lowest poverty concentration, with the greatest association found in the 20% or greater poverty concentration (aIRR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.41-2.49). No association was found between suicides by suffocation or poisoning and county poverty concentration.

In our exploratory models, the youth’s sex did not significantly moderate the association of county poverty concentration with pediatric suicide rates. The association between suicide and poverty concentration for youths 5 to 14 years of age (aIRR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.31-3.13 in the highest compared with the lowest poverty concentration) was greater than the association among children 15 to 19 years of age (aIRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04-1.49; interaction effect: aIRR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.02-2.59). The association between suicide and poverty concentration for children of other races/ethnicities (aIRR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.79-4.94 in the highest compared with the lowest poverty concentration) was greater than the association of suicide and poverty concentration among white non-Hispanic children (aIRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.48; interaction effect: aIRR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.43-4.17). The association between suicide and poverty concentration was not significantly different for black non-Hispanic children or Hispanic children compared with white non-Hispanic children.

Discussion

In this study, we found that higher suicide rates among US youths aged 5 to 19 years were associated with increasing county poverty concentration in a stepwise manner, after controlling for demographic characteristics and county urbanicity. County poverty concentration was associated with higher pediatric suicide rates by firearms but not by suffocation or poisoning. We found a 57% increase in suicide rates from 2007 to 2016 among youths aged 5 to 19 years. More recent data from 2017 suggest that suicide rates are continuing to increase.1

Particular groups of youths are differentially affected by suicide, including youths aged 15 to 19 years (relative to younger youths), male youths, and white youths.1 Suicides cluster geographically, with a prior study8 demonstrating mixed associations between area socioeconomics and suicide rates. Studies performed at more granular geographic levels of analysis, such as the county or community level, have been more likely to demonstrate an inverse association, with higher suicide rates in lower socioeconomic areas.8 Limited prior studies6,24,25 have examined suicide by socioeconomic status in the pediatric population. Socioeconomic factors previously associated with pediatric suicide include household receipt of public assistance, parental unemployment, and poor parental educational attainment. County-level poverty concentration as an additional associated risk factor may reflect contributions from individual household poverty and neighborhood variables, which we were unable to differentiate in this study.

Poverty is associated with worse health outcomes in children, including infant mortality, child abuse, and injury.3,4,18 Children living in poverty experience higher rates of chronic disease, including more frequent asthma attacks, increased lead levels, and higher rates of substance abuse.26,27 Neighborhood poverty has an association with child health outcomes beyond that of individual family poverty.28 Children born into neighborhood poverty, but not into household poverty, are at higher risk for externalizing mental conditions than children not born into poverty.5 For suicide specifically, a Canadian study7 found neighborhood poverty to be associated with suicidal thoughts and attempts, even after controlling for family socioeconomic status and individual child characteristics.

Poverty could be associated with an increased suicide risk through a variety of potential mechanisms. It may affect early brain development through long-term exposure to toxic levels of stress, with neurobiological stress–mediated pathways ultimately leading to impaired decision-making, behavioral self-regulation, and mood or impulse control.27,29 Multiple childhood adversities are more commonly experienced by children living in poverty, and these adversities have been associated with increased suicide risk in adolescents and young adults.6,30 Children living in poor neighborhoods are exposed to more family turmoil, violence, social isolation, and lack of positive peer influences.27,28,31 Youth living in poor neighborhoods also experience increased hopelessness; more internalizing problems, such as depression and anxiety; and increased externalizing mental conditions.5,32,33 Furthermore, areas of concentrated poverty may lack infrastructure, such as quality schools, sustainable jobs, health care facilities, and mental health resources, that support good health.27 Future research should work to delineate which of these factors contributes most strongly to the increased risk of pediatric suicide in counties with a high poverty concentration.

In our study, we found that the association of county poverty concentration with pediatric suicide varied by method. We stratified by method in the analyses because we hypothesized that the type of suicide method could vary by poverty concentration. In addition, understanding potential differences in suicide methods could be used to inform suicide prevention strategies.34 Of note, we found an association with poverty concentration only for firearm suicides. Firearms are the most lethal means of suicide when attempted.35 Four-fifths of adolescent suicides by firearms occur in the adolescent’s own home, and most adolescents use firearms owned by the parents.36 The presence of a firearm in a household is associated with a significant, but modifiable, risk for suicide among adolescents.37,38 Measures to increase safe firearm storage (such as keeping guns locked and unloaded, with ammunition locked and away from the firearm) are associated with reduced risk of youth unintentional injury or suicide by firearms.39,40 Because areas of high poverty concentration also experience higher rates of unintentional firearm deaths, further study is needed to determine whether children living in these areas have increased access to firearms or less safe firearm storage.18

The increased risk of pediatric suicide in high poverty areas may have implications for suicide prevention efforts. Effective interventions have been delivered in school, community, and health care settings for universal programs and targeted programs for high-risk individuals.2 For instance, the school-based program Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe reduced suicide attempts and severe suicidal ideation by approximately 50% at a 12-month follow-up in a multicenter cluster randomized clinical trial.41 The Zero Suicide Approach is an effective model for health care settings that incorporates commitment by health care leadership, practitioner training, attention to screening and assessment, use of a systematic suicide care protocol, and evidence-based treatment strategies.42 We found similar unadjusted rates of pediatric suicide among the different county poverty concentrations; thus, equal allocation of prevention resources regardless of county poverty concentration could be considered. Nevertheless, prevention efforts must also address upstream risk factors for suicide. The independent association between county poverty concentration and pediatric suicide in the multivariable model should prompt research into potential mediators through which poverty might convey an elevated suicide risk. It is unknown whether focused implementation of suicide prevention programs in high poverty areas could have potential for increased yield. On a more societal level, strategies that combat poverty, such as increasing the minimum wage, may be part of a multipronged strategy to consider for reducing youth suicide.43,44

Limitations

Our results must be considered in the context of the limitations of our study. Because the CMF is an administrative database, there is potential for misclassification of demographics or cause of death. Current estimates of demographic misclassification on death certificates are as high as 40% for American Indian or Alaska Native individuals, 3% for Hispanic individuals, and 3% for Asian or Pacific Islander individuals.45 Attribution of deaths as intentional or unintentional may sometimes be difficult to determine.46 We were unable to analyze data on a more granular geographic level, such as census tracts, which may be more sensitive to economic differences than counties or zip codes.20,26 Counties are heterogeneous and may consist of smaller communities of varying poverty concentration (ie, a city and its suburbs). As a result, the county poverty concentration reflects a combination of its communities, which may underestimate associations of poverty with suicide rates. Because markers of individual household socioeconomic status were unavailable in the databases used, we were unable to determine what proportion of the increased suicide risk was attributable to individual household poverty vs neighborhood-level poverty. We were also unable to explore the mechanisms connecting area poverty and suicide. Because the study was conducted in the United States, our findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the world.

Conclusions

In the United States, increased suicide rates among children were associated with increasing levels of county poverty concentration. This association was most prominent for firearm suicides. As pediatric suicide rates in the United States continue to increase, understanding of the upstream contributors to pediatric suicide, including poverty-related factors, appears to be needed so that suicide prevention efforts can focus on the youths at highest risk.

eTable. Suicide Methods Among Children 5-19 Years Old, 2007-2016

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/statistics/index.html. Published 2005. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 2.Calear AL, Christensen H, Freeman A, et al. . A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(5):467-482. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0783-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Council on Community Pediatrics Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell CA, Fleegler EW, Monuteaux MC, Wilson CR, Christian CW, Lee LK. Community poverty and child abuse fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20161616. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roos LL, Wall-Wieler E, Lee JB. Poverty and early childhood outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20183426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björkenstam C, Kosidou K, Björkenstam E. Childhood adversity and risk of suicide: cohort study of 548 721 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. BMJ. 2017;357:j1334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupéré V, Leventhal T, Lacourse E. Neighborhood poverty and suicidal thoughts and attempts in late adolescence. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1295-1306. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800456X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehkopf DH, Buka SL. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):145-157. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500588X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontanella CA, Saman DM, Campo JV, et al. . Mapping suicide mortality in Ohio: a spatial epidemiological analysis of suicide clusters and area level correlates. Prev Med. 2018;106:177-184. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson AM, Woodside JM, Johnson A, Pollack JM. Spatial patterns and neighborhood characteristics of overall suicide clusters in Florida from 2001 to 2010. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File, 1999-2016 (Machine Readable Data File and Documentation, CD-ROM Series 20, No. 2V) as Compiled From Data Provided by the 57 Vital Statistics Jurisdictions Through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian B, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(5):1-76. https://www.cdc.gov/. Accessed February 9, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Census Bureau County intercensal datasets: 2000-2010. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-counties.html. Accessed February 9, 2019.

- 14.US Census Bureau Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/estimates-characteristics.html. Accessed February 9, 2019.

- 15.US Census Bureau Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe.html. Accessed February 9, 2019.

- 16.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Rural-urban continuum codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 17.Annest J, Hedegaard H, Chen L, Warner M, Small E; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Proposed framework for presenting injury data using ICD-10-CM external cause of injury codes. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/icd-10-cm_external_cause_injury_codes-a.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2019.

- 18.Karb RA, Subramanian SV, Fleegler EW. County poverty concentration and disparities in unintentional injury deaths: a fourteen-year analysis of 1.6 million U.S. fatalities. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312-323. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader M-J, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US). Public Health Rep. 2003;118(3):240-260. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50245-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Census Bureau Poverty thresholds. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html. Accessed March 31, 2019.

- 22.Fontanella CA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Phillips GS, et al. . Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996-2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):466-473. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nance ML, Carr BG, Kallan MJ, Branas CC, Wiebe DJ. Variation in pediatric and adolescent firearm mortality rates in rural and urban US counties. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1112-1118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2002;325(7355):74. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Gibson-Davis CM. Effects of statewide job losses on adolescent suicide-related behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1964-1970. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(3):186-199. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pascoe JM, Wood DL, Duffee JH, Kuo A; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Council on Community Pediatrics . Mediators and adverse effects of child poverty in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudry A, Wimer C. Poverty is not just an indicator: the relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3)(suppl):S23-S29. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232-e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halfon N, Larson K, Son J, Lu M, Bethell C. Income inequality and the differential effect of adverse childhood experiences in US children. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7S):S70-S78. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arango A, Opperman KJ, Gipson PY, King CA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among youth who report bully victimization, bully perpetration and/or low social connectedness. J Adolesc. 2016;51:19-29. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Smith A, Spirito A, Boergers J. Neighborhood predictors of hopelessness among adolescent suicide attempters: preliminary investigation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(2):139-145. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.139.24400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):554-563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. . Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064-2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. The epidemiology of case fatality rates for suicide in the northeast. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(6):723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson RM, Barber C, Azrael D, Clark DE, Hemenway D. Who are the owners of firearms used in adolescent suicides? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(6):609-611. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides: a case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989-2995. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1820470. Accessed February 19, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470210057032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knopov A, Sherman RJ, Raifman JR, Larson E, Siegel MB. Household gun ownership and youth suicide rates at the state level, 2005-2015. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(3):335-342. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. . Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monuteaux MC, Azrael D, Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657-662. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. . School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1536-1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hogan MF, Grumet JG. Suicide prevention: an emerging priority for health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):1084-1090. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gertner AK, Rotter JS, Shafer PR. Association between state minimum wages and suicide rates in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):648-654. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dow WH, Godøy A, Lowenstein CA, Reich M; National Bureau of Economic Research Can Economic Policies Reduce Deaths of Despair? 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w25787. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 45.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J; National Center for Health Statistics; US Census Bureau . The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shain B; Committee on Adolescence . Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Suicide Methods Among Children 5-19 Years Old, 2007-2016