This case series assesses patient outcomes before and after recall of a defective pacemaker model to evaluate whether information provided to patients and caregivers was timely and complete.

Key Points

Question

Do the medical device industry and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provide timely information about product defects so that patients and their physicians can make fully informed decisions regarding management?

Findings

In this case series, the outcomes of 90 patients before and after the recall of a cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker in November 2015 were examined along with review of the FDA Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database and showed that the manufacturer and the FDA were aware of battery and wire connection defects for more than 1 year before patients began to develop serious adverse clinical events because of abrupt loss of pacing. The information included in the recall notification was incomplete, and the FDA underestimated the criticality of the pacemaker’s defects.

Meaning

The medical device industry and the FDA should focus on early recognition of device defects and fully and promptly disclose vital information to patients and their caregivers.

Abstract

Importance

Timely and complete disclosure of medical device defects is necessary to manage patient care safely and effectively.

Objectives

To determine if the manufacturer’s recommendations following the recall of a medical device were timely and complete, the follow-up information and data provided to patients and physicians were adequate for managing patient care, and the actions taken by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the recall were appropriate.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This single-center retrospective case series included 90 of 448 patients who were implanted with a cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker at the Minneapolis Heart Institute from May 2003 through January 2011; this pacemaker was recalled in November 2015. In addition, returned product reports submitted by the manufacturer to the FDA via the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database from January 2008 through December 2018 were analyzed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinical outcomes were serious adverse clinical events that occurred before and after the November 2015 recall notifying physicians and patients that the device’s battery could fail unexpectedly because of high internal impedance. Technical outcomes were signs and causes of failure.

Results

Five of 90 patients observed during 2015 experienced syncope when their pacemakers stopped pacing owing to battery or wire connection defects prior to the recall. Of the 90 patients, 37 (41%) were men, and the median (interquartile range) age at implantation was 71.3 (66.1-78.2) years. Analysis of the MAUDE data revealed that battery failures prior to the recall were associated with serious adverse events that included 1 death, 1 cardiac arrest, 5 syncopal attacks, and 6 heart failure exacerbations; 3 additional prerecall syncopal events were caused by wire connection defects. The manufacturer and the FDA were aware of the battery and wire connection defects for 19 months before issuing the recall, yet the wire connection problem was not included in the advisory and physicians were not informed that interrogating the pacemaker could result in loss of pacing. The FDA classified the recall as class II rather than the more critical class I.

Conclusions and Relevance

This case series study of patients implanted with a defective pacemaker found that the pacemaker recall was delayed and that subsequent communications did not include all critical information needed for safe and effective patient care. These findings should prompt reforms in how the medical device industry and the FDA manage future medical device recalls.

Introduction

Medical device safety in the United States is a major public concern.1 However, little is known about outcomes before and after a life-sustaining medical device is found to be defective and is recalled. Similarly, to our knowledge, the appropriateness of specific actions by manufacturers and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to mitigate potential clinical risks posed by recalled implantable devices in high-risk patient populations has not been assessed.

In November 2015, Medtronic notified physicians that its InSync III model 8042 cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) could fail unexpectedly because of high internal battery impedance (HIBI) caused by the buildup of a resistive film on the cathode current collector.2 High internal battery impedance decreases current flow from the battery and may result in abrupt cessation of pacing. The manufacturer’s modeling estimated that the risk of failure for the approximately 9300 devices that remained implanted in the United States at that time was 0.16% to 0.6%.2

For patients who are dependent on the pacemaker, the manufacturer recommended that physicians should weigh the risks and benefits of device replacement on an individual patient basis and estimated that the per-patient mortality risk was very low (0.007% to 0.02%).2 The company stated it would provide updates in its semiannual product performance reports.

The FDA classified this recall as class II, meaning the device could cause temporary or medically reversible health consequences but that the probability of serious adverse health consequences was remote. The recall notification did not mention any other product performance issues.

The objective of this study was to examine the Minneapolis Heart Institute (MHI) experience with the recalled pacemakers to determine if (1) the manufacturer’s recommendations were timely and complete, (2) the follow-up information and data were adequate for managing patient care safely and effectively, and (3) the response and recall classification by the FDA were appropriate. To supplement the clinical data, we assessed the manufacturer’s engineering analyses of failed devices, which are publicly available in the FDA Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database.

Methods

Study Design

This investigator-initiated single-center retrospective case series included patients treated at MHI and data from the MAUDE database. The protocol was approved by the Allina Health Institutional Review Board. Patient informed consent was waived because this retrospective analysis involved no more than minimal risk to patients and the results would not affect clinical decisions or outcomes of the patients included in the study.

InSync III Pacemaker

The device is a CRT-P that has a lithium-hybrid cathode battery. It received the European certification mark in 2001 and entered the US market in February 2003. Between those dates and 2011, when this model was discontinued, 96 800 of the pacemakers were implanted worldwide, including 39 511 in the United States. At the time of the November 2015 recall, there were approximately 9300 active implants in the United States and 22 000 worldwide.2

Study Population

Patients were included if they had undergone implantation with the pacemaker from 2003 through 2011 at MHI and were actively observed at MHI during November 2015. The characteristics of these patients are given in the eTable in the Supplement. Standard techniques were used to perform the CRT-P implantations. Pacing optimization was done after implantation. Patients were observed in the pacemaker clinic. Patients were excluded if they did not permit the use of their medical records for research.

Data

Patient and device data were obtained from hospital and clinic records. Pacemaker dependency was defined as the absence of a stable escape rhythm or the development of symptoms of bradycardia on cessation of pacing. All patients who had complete atrioventricular block created by atrioventricular node ablation were considered pacemaker dependent.

The results of engineering analyses of failed device leads were obtained from the manufacturer. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were death, cardiac arrest, syncope, and new or worsening heart failure.

FDA MAUDE Database

The MAUDE database contains reports of adverse events involving medical devices that are reported to US manufacturers by users worldwide. It includes medical devices that are implanted, have been explanted, or are used externally. The medical device reports are publicly available online for the previous 10 years.3

During February 2019, the MAUDE database was queried for reports related to the device using the search terms battery, premature, analysis, high, and no output for the years 2008 through 2018. These data were extracted from the reports: (1) dates of manufacture, clinical event, receipt of the explanted device by the manufacturer, and receipt of the manufacturer’s report by the FDA; (2) clinical information and signs of device failure that were reported to the manufacturer; and (3) results of the manufacturer’s analysis of the returned devices.

Timelines

Clinical events at MHI and device failures in the MAUDE database were classified as prerecall or postrecall. The time interval before or after the recall was the difference between the date of the recall (November 9, 2015) and the date of the MHI clinical event or the date the FDA received the manufacturer’s MAUDE report. For these prerecall and postrecall time intervals, we identified the number of pacemakers that failed because of HIBI or lifted bond wires and the number of patients who experienced SAEs. The information in the MAUDE database did not allow consistent identification of precisely when the manufacturer became aware of a device failure or its cause; consequently, delays in reporting a failure or its cause to the FDA could not be determined.

Product Performance Reports

The manufacturer’s product performance reports subsequent to the recall (2016 through 2018) were examined for device information and updates.4 These data are based on US implants, whereas MAUDE reports include devices implanted outside the United States; thus, there may be numerical differences between the product performance report data and MAUDE data.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as counts and percentages for categorical variables. Because the study is descriptive in nature and had no formal comparator group, statistical comparisons were not performed. All descriptive statistical summaries were performed in Excel (Microsoft Corp, version 16.0). Data analysis occurred from July 2019 through October 2019.

Results

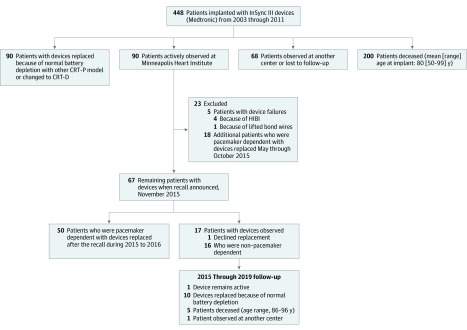

Patients at MHI

Of the 448 patients who received this model of pacemaker from 2003 through 2011 at MHI, 90 were observed when the first pacemaker failed in May 2015 (Figure 1). Seventy of these patients (78%) were pacemaker dependent; 13 patients had no stable underlying rhythm and 57 patients had radiofrequency atrioventricular node ablation at the time of pacemaker implantation.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Showing the Outcomes of Patients Who Underwent Implantation of a Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Pacemaker (CRT-P) at Minneapolis Heart Institute From May 2003 Through January 2011.

CRT-D indicates cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; HIBI, high internal battery impedance.

Between the first failure and the November 2015 recall, 5 patients (6%) at MHI experienced 1 or more syncopal episodes when their pacemakers permanently or intermittently stopped pacing because of a defect that was subsequently confirmed by the manufacturer. The median (interquartile range) time from device implantation was 6.7 (6.6-7.8) years. These cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patients at Minneapolis Heart Institute With Pacemaker Failures.

| Patient No. | Cardiac Disease | Rhythm/Conduction | PG Implant Time, y | Failure Sign | Clinical Consequence | Results of Manufacturer’s Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RHD; MVR; LVD | AF/CHB; AVN ablation | 6.7 | Rapid battery depletion; intermittent no output; asystole during telemetry | Recurrent syncope | High internal battery impedance |

| 2 | ICM; CABG | AF/CHB | 7.8 | No output | Syncope; dyspnea | Lifted bond wires on electronic circuit |

| 3 | Hypertension | AF/CHB; AVN ablation | 6.6 | Rapid battery depletion; no output | Syncope; dyspnea | High internal battery impedance |

| 4 | Pulmonary hypertension | AF/CHB; AVN ablation | 8.7 | Intermittent no output | Syncope; dyspnea | High internal battery impedance |

| 5 | MVR; HFpEF | AF/CHB | 6.1 | Intermittent no output | Syncope | High internal battery impedance |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; AVN, atrioventricular node; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; CHB, complete heart block; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; LVD, left ventricular dysfunction; MVR, mitral valve replacement; PG, pulse generator; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Patient 1 became syncopal when the CRT-P intermittently ceased pacing. During telemetric interrogation, the device abruptly stopped pacing, and emergency temporary pacing was required. The pacemaker was replaced, and the manufacturer’s analysis concluded that the device had failed because of HIBI.

Patient 2 was hospitalized after several falls and worsening heart failure symptoms. During telemetric interrogation, the device ceased pacing for 9 seconds. The CRT-P was replaced emergently; the manufacturer found that the cause of failure was lifted bond wires on the electronic circuit.

Patients 3, 4, and 5 experienced loss of pacing because of device failure caused by HIBI. They underwent uneventful pulse generator replacement.

A sixth patient died unexpectedly prior to the recall, but the patient’s pacemaker was not interrogated or removed postmortem. The pacemaker evaluation 1 month earlier was normal.

Although the manufacturer stated that its worldwide data did not suggest a systematic performance issue, MHI decided to prophylactically replace the devices in patients who were pacemaker dependent. By the date of the recall (November 9, 2015), MHI had electively replaced 18 additional pulse generators (Figure 1). Following the recall, 50 additional patients at MHI underwent prophylactic pulse generator replacement. Of the 73 prophylactic replacements, 1 patient, who was receiving therapeutic warfarin for atrial fibrillation, developed a pocket hematoma that required surgical evacuation.

Sixteen patients who were not pacemaker dependent did not undergo device replacement, and 1 patient who was pacemaker dependent declined device replacement. As of June 2019, no further device-related or procedure-related adverse events had occurred.

MAUDE Data

The MAUDE database search found 205 devices that had been returned to the manufacturer from November 2008 through January 2019. Of these, 158 devices (77.1%) failed because of HIBI, 35 (17.1%) failed because of lifted bond wires on the pacemaker’s electronic circuit, and 12 (5.9%) failed because of normal battery depletion.

Nearly one-third (50 of 158 [31.6%]) of the pacemakers exhibited no output or loss of capture owing to HIBI; of these, 8 (16%) occurred during pacemaker telemetry or programming (Table 2). Seven of 35 pacemakers (20%) exhibited no output or loss of capture caused by lifted bond wires. Seventeen of 35 pacemakers (49%) replaced prophylactically because of the recall were found to have no output owing to lifted bond wires.

Table 2. Signs and Causes of Pacemaker Failure in the US Food and Drug Administration Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience Database.

| Sign | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIBI (n = 158) | Lifted Bond Wires (n = 35) | Normal Battery Depletion (n = 12) | |

| No output | 10 (6.3) | 3 (9) | 0 |

| During telemetry | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Loss of capture | 40 (25.3) | 4 (12) | 0 |

| During telemetry | 5 (3.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Loss of CRT | 8 (5.1) | 2 (6) | 1 (8) |

| Loss of telemetry | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Battery | |||

| Rapid depletion | 13 (8.2) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) |

| Fluctuating voltage | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Premature depletion | 53 (33.5) | 1 (3) | 7 (58) |

| Prophylactic replacement | 17 (10.8) | 17 (50) | 0 |

| No output at RPA | 0 | 17 (50) | 0 |

| Variable lead impedance | 3 (1.9) | 4 (12) | 0 |

| Elective replacement indicator | 6 (3.8) | 2 (6) | 2 (17) |

| Power-on reset | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| None | 1 (0.6) | 1 (3) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; HIBI, high internal battery impedance; RPA, returned product analysis.

Serious adverse events included death, cardiac arrest, and syncope (Table 3). Pacemaker failures owing to HIBI were associated with 19 SAEs, including 1 death that occurred prior to the recall notification; lifted bond wires were associated with 3 SAEs. Heart failure symptoms occurred in 24 patients, including loss of cardiac resynchronization therapy in at least 8 patients.

Table 3. Adverse Events and Their Causes Before and After the Pacemaker Recall in the US Food and Drug Administration Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience Database.

| Characteristic | Recall, No. | Total, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prerecall | Postrecall | ||

| Adverse event | |||

| Total, No. | 19 | 39 | 58 |

| Death | 1 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | 1 | 2 (4) |

| Syncope | 8 | 11 | 19 (33) |

| Asystole | 1 | 4 | 5 (9) |

| Presyncope/dizziness | 2 | 5 | 7 (12) |

| Heart failure/dyspnea/weakness | 6 | 18 | 24 (41) |

| Cause | |||

| High internal battery impedance | 15 | 38 | 53 (91) |

| Lifted bond wires | 3 | 0 | 3 (55) |

| Fractured interconnect ribbon | 1 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Normal battery depletion | 0 | 1 | 1 (2) |

A total of 34 of 205 pacemakers were replaced prophylactically as a result of the advisory. Analysis of these 34 devices found that 17 (50%) had HIBI, 3 (9%) had lifted bond wires, and 14 (41%) had both HIBI and lifted bond wires.

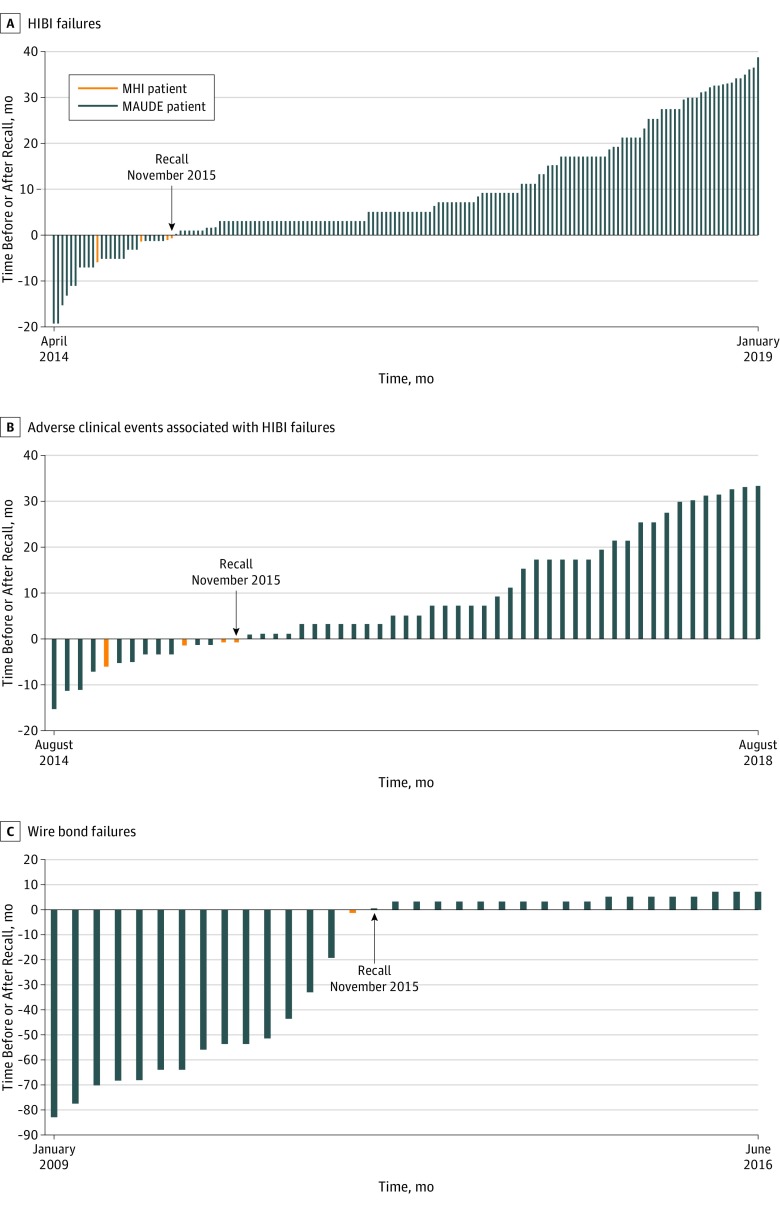

Temporal Associations

Analysis of the temporal associations between pacemaker HIBI failures, SAEs, and the date of the recall showed that the FDA received the first MAUDE report of pacemaker failure owing to HIBI on April 11, 2014, which was 19 months before the manufacturer sent the recall letter to physicians (Figure 2A). During those 19 months, the FDA received 22 additional reports from the manufacturer describing device HIBI failures; 11 of these reports detailed SAEs that included death, cardiac arrest, syncope, and heart failure (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Timeline for Device Failures and Adverse Events Before and After Recall of the Pacemaker on November 9, 2015.

A, Each vertical bar represents 1 device found to have high internal battery impedance (HIBI). B, Each vertical bar represents 1 serious adverse clinical event associated with a device HIBI failure. C, Each vertical bar represents a device failure owing to lifted bond wires; 3 adverse events were associated with this defect and all occurred prior to the recall.

MAUDE indicates Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database; MHI, Minneapolis Heart Institute.

The first device HIBI failure at MHI occurred in May 2015, which was 13 months after the manufacturer reported the first HIBI failure to the FDA and 6 months before the recall in November 2015. Three additional patients at MHI experienced device HIBI failures less than 2 months before the recall.

The FDA received 15 reports of device failures owing to lifted bond wires prior to the device HIBI recall notification (Figure 2C); 3 of these failures were associated with syncope. The first device failure owing to lifted bond wires was reported to the FDA in January 2009. Thirteen additional failures owing to lifted bond wires were reported to the FDA prior to the device recall. The lifted bond wire failure that occurred in 1 patient treated at MHI occurred nearly 7 years after the first device lifted bond wire failure and less than 2 months before the recall.

Product Performance Updates

The manufacturer provided 5 device updates in its semiannual product performance reports for 2016 through 2018. During this time, 101 device malfunctions occurred, including 27 battery failures and 12 electrical interconnect failures that compromised pacemaker therapy. The electrical interconnect failures included lifted bond wires. The recall updates did not mention either the electrical interconnect defect or the risk of no pacing output or loss of capture that could occur during pacemaker telemetry or programming. The manufacturer did not change its original estimated failure rate (0.16% to 0.6%)2 for the devices.

Discussion

Our clinical experience and the results of the MAUDE database analysis suggest that neither the manufacturer nor the FDA comprehended the clinical risks posed by the pacemaker’s defects. This conclusion is supported by the findings that (1) the manufacturer and the FDA were aware of the battery problem and its clinical consequences for at least 19 months prior to the recall, (2) physicians and patients were never informed of the lifted bond wire (electrical interconnect) problem, (3) physicians were not told that interrogating or programming the pacemaker could result in abrupt loss of pacing, (4) no meaningful product updates were issued by the manufacturer or mandated by the FDA subsequent to the recall, even though the number of failures increased after the recall, and (5) the FDA classified the recall as class II (no immediate danger of death or serious injury) rather than class I (significant risk of death or serious injury) and did not change it despite additional SAEs.

The first failure of devices that were implanted at MHI occurred in May 2015. However, the MAUDE data show that during the 2 years prior to the recall, 23 confirmed pulse generators failed because of HIBI, resulting in 1 death, 1 cardiac arrest, and 9 other SAEs. Also during this time, 15 device failures owing to lifted bond wires were reported, causing syncope in 3 patients. These were the MAUDE data available to the FDA when it was determining the recall classification. Thus, it is unclear why the FDA concluded that the recall was a less-emergent class II and why the notification did not include the failures owing to lifted bond wires. Had all available information been disclosed, we believe physicians and their patients could have made a more informed decision regarding prophylactic replacement.

The buildup of a resistive film on the cathode current collector increased the battery’s internal impedance, thereby limiting the flow of current until the device could not deliver effective pacing pulses (Medical Device Report No. 5272525). We suspect that the loss of output during telemetric interrogation was related to this limitation of current flow and should have been anticipated by the manufacturer and the FDA. Another manifestation of limited current flow was intermittent pacing that may be undetectable during routine checks. At no time did the manufacturer or the FDA mention that intermittent loss of capture may be a manifestation of HIBI or that extended electrocardiographic monitoring may be required to identify this failure mode.

The undisclosed lifted bond wire problem was experienced by 1 of the patients observed at MHI, and the MAUDE search identified 15 additional cases. The manufacturer’s analysis of 1 device concluded that the failure owing to lifted bond wires was the result of weakening of the bond at the aluminum/gold intermetallic interface (Medical Device Report No. 5121081); this pacemaker was removed from a patient who had syncope, falls, and 9-second pauses when the device suddenly had no output. Seventeen pacemakers that were removed prophylactically had no output owing to lifted bond wires when tested in the manufacturer’s laboratory. Thus, the problem of lifted bond wires was a recurring device defect, posed a serious health risk, and should have been included in the recall.

The updates provided by the manufacturer in its product performance reports failed to find a correlation of device defects (eg, electrical interconnect) with adverse clinical events. The updates did not mention the need for caution when interrogating or programming the pacemaker. Although a substantial number of malfunctions occurred during 2016 through 2018, the manufacturer’s risk estimates did not change after the recall. In 2006, in response to several recalls involving implantable pacemakers and defibrillators, the Heart Rhythm Society, American College of Cardiology, and American Heart Association recommended that manufacturers’ product performance reports “should include all device information pertinent to patient care.”5 The device recall and subsequent updates ignored this recommendation.

The recall letter that the manufacturer sent to physicians stated that the “estimated per patient mortality risk of this issue (0.007% to 0.02%) is comparable to the estimated per patient mortality risk of complications associated with an incremental, early device replacement (0.005%).”2 By implication, there would be no mortality benefit in patients who were pacemaker dependent if their pulse generators were replaced prophylactically. To our knowledge, this assertion, although possibly correct, is not based on published data from studies of patients with heart failure or patients who have undergone radiofrequency atrioventricular node ablation and are pacemaker dependent. Notably, for the devices in the MAUDE database that were replaced prophylactically, a high proportion (30 of 34 [88%]) had evidence of HIBI, and some had lifted bond wires.

Timely notification of medical device defects is necessary to limit the exposure of patients to products that are unreliable and/or pose a notable health risk.5 Methods exist that can identify device issues earlier than the passive surveillance system currently used by the FDA.6,7 Hauser et al6 showed that DELTA (Data Extraction and Longitudinal Trend Analysis), a computerized automated safety surveillance tool, could have identified an implantable defibrillator lead problem7 substantially sooner than was achieved through existing postmarket surveillance methods. Subsequently, Resnic et al8 prospectively applied DELTA to a large registry of implantable vascular closure devices and were able to rapidly identify safety signals (vascular complications, access site bleeding) involving a specific vascular closure device. Such techniques can be applied to robust clinical and industry databases as well as national and regional health care registries. We suggest that similar safety monitoring tools should be adopted by the medical device industry and encouraged by the FDA. We further suggest that industry and the FDA review their processes for informing patients and physicians of critical device performance issues, especially for vulnerable populations who depend on their devices for life-sustaining therapy.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Not all patients who were implanted with this pacemaker at MHI were observed; consequently, some patients in the MHI cohort may have experienced device failure without our knowledge. The MAUDE database contains only a fraction of failed devices because many are buried with the patient and those that are explanted are often not returned to the manufacturer for analysis. It is also possible that our search terms did not identify all MAUDE reports relevant to the study. Thus, it is likely that the actual number of failed pulse generators in the MAUDE database and possibly in the MHI implant population is considerably higher.

Conclusions

The heart failure pacemaker recall was unnecessarily delayed and did not include all the critical information needed for patient management. We believe these deficiencies negatively affected the outcomes in patients at MHI and those represented in the FDA MAUDE database. These findings should prompt reforms in how the medical device industry and the FDA conduct medical device surveillance and manage future recalls.

eTable. Patient demographic information and characteristics.

References

- 1.Editorial Board 80,000 Deaths. 2 Million injuries. It’s time for a reckoning on medical devices. New York Times May 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/04/opinion/sunday/medical-devices.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- 2.Samsel T. Urgent medical device correction: InSync III cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers (CRT-P) models 8042, 8042B, 8042U. http://www.medtronic.com/insync-iii-crt-p/. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration. MAUDE—Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/search.cfm. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- 4.Medtronic. Performance reports. http://wwwp.medtronic.com/productperformance/past-reports.html. Accessed June 23, 2019.

- 5.Carlson MD, Wilkoff BL, Maisel WH, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association; International Coalition of Pacing and Electrophysiology Organizations . Recommendations from the Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on Device Performance Policies and Guidelines Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) and the International Coalition of Pacing and Electrophysiology Organizations (COPE). Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(10):1250-1273. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauser RG, Mugglin AS, Friedman PA, et al. Early detection of an underperforming implantable cardiovascular device using an automated safety surveillance tool. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(2):189-196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser RG, Maisel WH, Friedman PA, et al. Longevity of Sprint Fidelis implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads and risk factors for failure: implications for patient management. Circulation. 2011;123(4):358-363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.975219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnic FS, Majithia A, Marinac-Dabic D, et al. Registry-based prospective, active surveillance of medical-device safety. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):526-535. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Patient demographic information and characteristics.