Key Points

Question

How do outcomes in idelalisib (IDEL) treatment of relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the clinical setting compare with the treatment outcomes in clinical trials?

Findings

In this cohort study of 115 clinical trial participants and 599 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older treated with IDEL, Medicare beneficiaries were older, sicker, and had unfavorable imbalances in treatment duration, mortality, and fatal infections compared with clinical trial participants.

Meaning

Patients treated with IDEL in the clinical setting had less favorable treatment outcomes than those in clinical trials.

This cohort study compares idelalisib treatment outcomes in the clinical setting among Medicare beneficiaries with outcomes in clinical trial data.

Abstract

Importance

Idelalisib (IDEL) is approved as monotherapy in relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) and with rituximab (IDEL+R) for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Toxic effects can be severe and treatment-limiting. Outcomes in a real-world population are not yet characterized.

Objective

We compared IDEL treatment outcomes in the clinical setting with outcomes in clinical trial data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study compared clinical trial participants treated with IDEL, aged 65 years or older, in studies 101-09 and 312-0116 with Medicare beneficiaries treated with IDEL of the same disease state and treatment regimen. Study 101-09 was a phase 2, single-group, open-label trial supporting accelerated approval of IDEL for relapsed or refractory FL. Study 312-0116 was a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial supporting approval of IDEL+R for relapsed CLL. Analyses were conducted between February and December 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Treatment duration, on-treatment and overall mortality, and serious and fatal infections were compared between trial participants and Medicare beneficiaries. Cox proportional hazards models quantified differences by cohort.

Results

We identified 26 trial participants (mean [SD] age, 73 [4.9] years; 12 [46.2%] women) and 305 Medicare beneficiaries (mean [SD] age, 76 [6.9] years; 103 [54.8%] women) receiving IDEL for FL and 89 trial participants (mean [SD] age, 74 [6.0] years; 30 [33.7%] women) and 294 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76 [6.3] years; 111 [37.8%] women) receiving IDEL+R for CLL. Medicare beneficiaries were older with higher comorbidity; had a shorter median treatment duration for CLL (173 days vs 473 days, P < .001) but not FL (114, days vs 160 days, P = .38); a numerically higher mortality rate (CLL: HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.93-2.11; FL: HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.69-2.78); and a significantly higher fatal infection rate per 100 person-years for CLL (18.4 vs 9.8, P = .04) and a numerically higher rate for FL (27.6 vs 18.6, P = .54), compared with trial participants. Trial participants had approximately twice as many dose reductions (CLL: 32.6% vs 18.0%; P = .003; FL: 38.5% vs 16.1%; P = .02). Among Medicare beneficiaries, a hospitalized infection within 6 months prior to IDEL initiation was associated with a 2.11-fold increased risk for on-treatment fatal infections (95% CI, 1.44-3.10). Despite a March 2016 recommendation for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis in patients treated with IDEL, prophylaxis rates were low after March 2016 (FL: 25%, CLL: 37%).

Conclusions and Relevance

We observed substantial imbalances in baseline comorbidities and treatment outcomes between Medicare beneficiaries and trial participants aged 65 years or older. Immunosuppression-related toxic effects, including infections, may have been somewhat reduced in trials by more frequent dose reductions and exclusion of patients with ongoing infections. Selective eligibility criteria and closer monitoring of trial patients may be responsible for limited generalizability of trial data to clinical practice.

Introduction

Idelalisib (IDEL) is an oral phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), in combination with rituximab. Idelalisib also received accelerated approval for relapsed follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (FL) and relapsed small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), after 2 or more prior systemic therapies.

Although trials supporting IDEL approval had an acceptable risk-benefit profile, 7 subsequent trials were halted in March 2016, for a higher incidence of serious and fatal adverse events in patients treated with IDEL.1,2,3 Multiple safety communications described risk for serious and fatal Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP), recommending prophylaxis in all treated patients.1,3,4

Given these safety findings, we reanalyzed primary source clinical trial data sets obtained from the IDEL manufacturer to reassess treatment outcomes among trial participants aged 65 years or older. These data were compared with clinical outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, focusing on IDEL/rituximab (IDEL+R) for CLL and IDEL for FL.

Methods

Data Sources

Trial Participants

Study 101-09 was a phase-2, single-group, open-label trial for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iNHL), supporting accelerated approval of IDEL in patients with relapsed FL or SLL who were double-refractory, to both an alkylator and rituximab.5 Twenty-six participants treated with IDEL had FL and were aged 65 years or older.

Study 312-0116 was a multicenter phase-3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing IDEL+R vs placebo+R in patients with relapsed CLL. Eighty-nine participants treated with IDEL+R were aged 65 years or older.6

This study was exempted from institutional review board approval and informed consent as necessary for protection of public health under the common rule, at 45-CFR-46.102(l)(2). Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc), R (version 3.4.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and OpenEpi statistical software (http://www.openepi.com). Analyses were conducted between February and December 2018.

Patients in the Clinical Setting

Medicare is a government-provided insurance for US citizens who are disabled or aged 65 years or older. Our study included inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures from fee-for-service Medicare Part A (inpatient hospitalization) and Part B (outpatient visits) in addition to prescription drugs (Part D). We identified beneficiaries aged 65 years or older who initiated IDEL for FL or IDEL+R for CLL from July 2014 (approval) through September 2016. To assess prior therapy and baseline comorbidity, beneficiaries were required to have Medicare enrollment for 1 year or longer before IDEL initiation. The CLL and FL cohorts were formed using diagnostic codes, and concomitant rituximab was defined as any administration during IDEL treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Patient Characteristics

Baseline comorbidity was described using the Medical Dictionary of Regulatory Activities.7 The modified Charlson comorbidity score, which has predictive value for 1-year mortality, was assessed for all patients.8,9 It was calculated using medical history and concomitant medications for trial participants and diagnostic coding and drug dispensings for Medicare beneficiaries.

Treatment Persistency and Dosage Reductions

Treatment duration was calculated from first IDEL dispensing until discontinuation (ie, last day supply). Gaps less than 90 days were allowed to account for short-term therapy interruptions for toxic effects. Reductions in daily dosage were notated throughout follow-up. Persistency plots depicted IDEL use by study cohort. Day-180 treatment discontinuation and dosage reductions were evaluated. Treatment discontinuation differences between cohorts, and the impact of age and Charlson score, were quantified using Cox proportional hazards models.

On-Treatment Mortality and Overall Mortality

Mortality data were obtained from clinical trial data sets and Social Security records for Medicare beneficiaries.10 On-treatment mortality was defined as death while taking idelalisib or within 30 days after discontinuation. Overall mortality was defined as death in any patient receiving 1 or more idelalisib doses. Day-180 on-treatment mortality was calculated. Mortality differences between cohorts, and the impact of age and Charlson score, were quantified using Cox proportional hazards models.

Serious and Fatal Infections

For trial participants, serious infections were defined as grade 3 or higher (ie, severe, life-threatening, or fatal), notated as serious (ie, requiring hospitalization, prolonged hospitalization, life-threatening, or fatal), or requiring intravenous antibiotics.11,12 For Medicare beneficiaries, this was implemented as infections during inpatient stays or emergent care stays requiring intravenous antibiotics; discharge diagnosis claims were reviewed manually for infection classification and potential causative pathogens. Fatal infections were defined as serious infections within 30 days before death.

Infections were identified from first IDEL dose until 30 days after discontinuation. They were described overall, among patients with a Charlson score of 3 or less, by day 180, and per 100 person-years. Among Medicare beneficiaries, a recent pretreatment serious infection (prior 6 months) was evaluated as a risk factor for on-treatment fatal infections using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for 5-year age bands, indication, and rituximab receipt.

Time-Series Analyses for PJP Prophylaxis and Overall Use

The impact of the manufacturer’s March 2016 Dear Healthcare Provider Letter recommending PJP prophylaxis with idelalisib was assessed using interrupted time-series analyses. A first-order autoregressive model was used to quantify differences in PJP prophylaxis and utilization rates by indication before vs after March 2016.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Medicare beneficiaries were older and had higher comorbidity than trial participants. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics for 26 trial participants and 305 Medicare beneficiaries receiving IDEL for FL and 89 trial participants and 294 Medicare beneficiaries receiving IDEL+R for CLL. Baseline characteristics for an additional 51 Medicare beneficiaries who received IDEL+R for FL and 250 Medicare beneficiaries who received IDEL for CLL are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics for Medicare Beneficiaries and Trial Participants by Study Cohort.

| Characteristic | Follicular Lymphoma, IDEL, No (%) | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, IDEL+R, No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 101-09 (n = 26) | Medicare (n = 305) | Study 312-0116 (n = 89)a | Medicare (n = 294) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 65-74 | 18 (69.2) | 138 (45.2) | 57 (64.0) | 140 (47.6) |

| ≥75 | 8 (30.8) | 167 (54.8) | 32 (36.0) | 154 (52.4) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 12 (46.2) | 167 (54.8) | 30 (33.7) | 111 (37.8) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 23 (88.6) | 284 (93.1) | 81 (91.0) | 262 (89.1) |

| Asian | 1 (3.8) | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Black | 0 | 8 (2.6) | 3 (3.4) | 24 (8.2) |

| Other | 2 (7.6) | 10 (3.3) | 5 (5.6) | 8 (2.7) |

| Region | ||||

| United States | 13 (50.0) | 305 | 63 (70.8) | 294 |

| Charlson score | ||||

| 2 | 19 (73.1) | 104 (34.1) | 31 (34.8) | 90 (30.6) |

| 3 | 4 (15.4) | 43 (14.1) | 37 (41.6) | 52 (17.7) |

| 4 | 2 (7.7) | 39 (12.8) | 14 (15.7) | 46 (15.6) |

| ≥5 | 1 (3.8) | 119 (39.0) | 7 (7.9) | 106 (36.1) |

| Baseline comorbidityb | ||||

| Cardiac | 9 (34.6) | 194 (63.6) | 27 (30.7) | 210 (71.4) |

| Endocrine | 6 (23.1) | 192 (63.0) | 30 (34.1) | 176 (59.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 (46.2) | 249 (81.6) | 61 (68.2) | 228 (77.6) |

| Hepatobiliary | 1 (3.8) | 80 (26.2) | 4 (4.5) | 70 (23.8) |

| Immune system | 7 (26.9) | 126 (41.3) | 17 (19.3) | 164 (55.8) |

| Infections and infestations | 10 (38.5) | 216 (70.8) | 48 (53.4) | 238 (81.0) |

| Metabolism and nutrition | 11 (42.3) | 238 (78.0) | 51 (56.8) | 252 (85.7) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 14 (53.8) | 251 (82.3) | 51 (56.8) | 249 (84.7) |

| Nervous system | 5 (19.2) | 145 (47.5) | 36 (40.9) | 130 (44.2) |

| Psychiatric | 8 (30.8) | 109 (35.7) | 35 (39.8) | 89 (30.3) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 3 (11.5) | 197 (64.6) | 50 (55.7) | 188 (63.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal | 6 (23.1) | 232 (76.1) | 51 (56.8) | 239 (81.3) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | 6 (23.1) | 190 (62.3) | 21 (23.9) | 221 (75.2) |

| Vascular | 15 (57.7) | 264 (86.6) | 56 (62.5) | 261 (88.8) |

Abbreviations: IDEL, idelalisib; IDEL+R, idelalisib with rituximab.

Renamed Study 312-0117 for the long-term follow-up extension phase.

Baseline comorbidity defined using the System Organ Class from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

Treatment Persistency and Dose Reductions

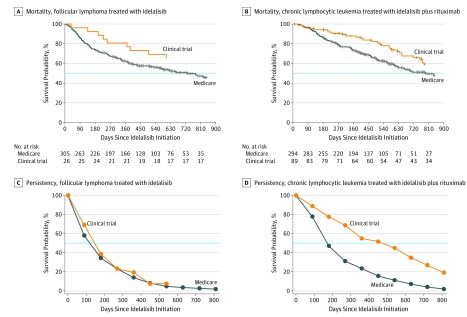

Compared with trial participants, Medicare beneficiaries receiving IDEL+R for CLL had a higher day-180 treatment discontinuation rate (43.2% vs 18.0%; P < .001) (Table 2) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The hazard ratio (HR) for discontinuation was 2.87 (95% CI, 1.77-4.65) on day 30 and decreased with follow-up time (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The day-180 discontinuation rate was high for patients treated with IDEL for FL irrespective of cohort (Medicare beneficiaries, 47.2%; Trial participants, 53.8%). Persistency plots are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Comparison of Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries and Clinical Trial Participantsa.

| Variable | IDEL for FL | IDEL+R for CLL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 101-09 (n = 26) | Medicare (n = 305) | P Value | Study 312-0116 (n = 89) | Medicare (n = 294) | P Value | |

| Duration and dose reductions | ||||||

| Treatment duration, median (IQR), days | 160 (60-250) | 114 (60-240) | .38 | 473 (212-754) | 173 (93-329) | <.001 |

| Dose reduction, % | 38.5 | 16.1 | .02 | 32.6 | 18.0 | .003 |

| Starting dose | ||||||

| 150 mg Twice daily | 100.0 | 83.6 | .02 | 100.0 | 89.8 | <.001 |

| 100 mg Twice daily | 0 | 13.4 | 0 | 9.9 | ||

| 150 mg Once daily | 0 | 2.0 | 0 | 1.0 | ||

| 100 mg Once daily | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.3 | ||

| Reasons for early censoring, by day 180 | ||||||

| Treatment discontinuation, % | 53.8 | 47.2 | .52 | 18.0 | 43.2 | <.001 |

| On-treatment mortality, % | 7.7 | 18.4 | .26 | 4.5 | 9.9 | .11 |

| Treatment discontinuation, HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| All patients, on day 180b | 0.86 (0.48-1.52) | 2.27 (1.58-3.26) | ||||

| Patients with Charlson score ≤3c | 0.76 (0.40-1.43) | 2.32 (1.55-3.47) | ||||

| Overall mortalityd | ||||||

| All patients | 1.39 (0.69-2.78) | 1.40 (0.93-2.11) | ||||

| Patients with Charlson score ≤3 | 1.08 (0.52-2.24) | 1.32 (0.76-2.31) | ||||

| On-treatment Infectionse | ||||||

| Serious infections | ||||||

| Rate per 100 PY | 67.1 | 78.7 | .69 | 81.6 | 80.1 | .90 |

| Overall, % | 30.8 | 39.7 | 64.0 | 48.3 | ||

| Charlson score ≤3, % | 30.4 | 29.9 | 55.9 | 37.3 | ||

| By day 180, % | 19.2 | 32.1 | 38.2 | 34.0 | ||

| Fatal infections | ||||||

| Rate per 100 PY | 18.6 | 27.6 | .54 | 9.8 | 18.4 | .04 |

| Overall, % | 11.5 | 15.1 | 14.6 | 13.3 | ||

| Charlson score ≤3, % | 13.0 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 10.6 | ||

| By day 180, % | 0.0 | 13.1 | 5.6 | 7.5 | ||

Abbreviations: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; FL, follicular lymphoma; IDEL, idelalisib; IDEL+R, idelalisib with rituximab; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; PY, person-years.

P values calculated using Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables.

The HRs were estimated from multivariable Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for age (5-year increments), sex, US location, Charlson score (linear and quadratic terms), and time interaction with indicator of Medicare beneficiaries. Estimates of HR on day 180 were presented here because the HR for treatment discontinuation was not constant over follow-up time. Refer to eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

The HRs were estimated from multivariable Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for age (5-year increments), sex, US location, and Charlson score (1-point increments).

The HRs were estimated from multivariable Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for age (5-year increments) and Charlson score (1-point increments).

See eTable 2 in the Supplement for rates of serious and fatal infections by anatomical location and eTable 3 in the Supplement for counts of serious and fatal infections by infection type.

Figure 1. IDEL Persistency and Overall Mortality Among Clinical Trial Participants and Medicare Beneficiaries by Study Cohort.

IDEL indicates idelalisib. The blue line indicates the median survival.

Each 5-year age increase was associated with a nonsignificant increase in treatment discontinuation (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.99-1.12). A 1-unit increase in Charlson score resulted in larger increases in treatment discontinuation for larger scores than for lower scores (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

In addition, approximately twice as many trial participants as Medicare beneficiaries experienced an IDEL dose reduction: 32.6% vs 18.0% (P = .003) with IDEL+R for CLL and 38.5% vs 16.1% (P = .02) with IDEL for FL (Table 2).

On-Treatment Mortality and Overall Mortality

Medicare beneficiaries had numerically higher day-180 on-treatment mortality for both IDEL for FL (18.4% vs 7.7%, P = .26) and IDEL+R for CLL (9.9% vs 4.5%, P = .11) compared with trial participants (Table 2) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). In addition, Medicare beneficiaries had numerically larger overall mortality rates than trial participants for both IDEL for FL (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.69-2.78) and IDEL+R for CLL (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.93-2.11) (Table 2) (Figure 1). With restriction to a Charlson score of 3 or less, the magnitude of these differences decreased for FL, but not meaningfully for CLL (Table 2).

Each 5-year age increase was associated with a 12% increased mortality rate (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02-1.22), whereas each 1-unit increase in Charlson score was associated with a 10% increased mortality rate (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Serious and Fatal Infections

The fatal infection rate per 100 person-years was significantly higher in Medicare beneficiaries than in trial participants in IDEL+R for CLL (18.4 vs 9.8, P = .04) and numerically higher in IDEL for FL (27.6 vs 18.6, P = .54) (Table 2). Infection rates were numerically higher during the first 6-months than during remaining study time (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). Pneumonia and sepsis were frequently observed. eTable 2 in the Supplement contains infection rates by anatomical location. eTable 3 in the Supplement provides counts by infection type.

Among Medicare beneficiaries, hospitalized infections within 6 months prior to IDEL-initiation were common (n = 173, 19.2%). A recent pretreatment hospitalized infection (0-6 months) was associated with a 2.11-fold (95% CI, 1.44-3.10) increased risk for on-treatment fatal infections.

Among beneficiaries hospitalized with serious on-treatment infections, 10 had PJP listed as a contributory cause, 4 of which were fatal. eTable 4 in the Supplement lists observed pathogens.

Time Trend Analyses

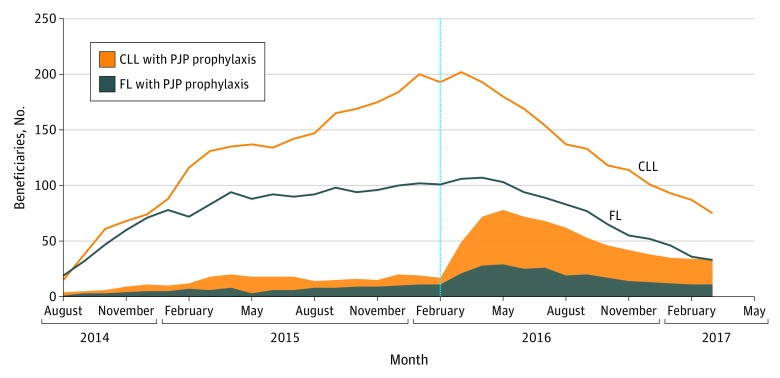

Prophylaxis rates among Medicare beneficiaries were significantly greater after the manufacturer's March 2016 safety communication for FL (8% before, 25% after, P < .001) and CLL (12% before, 37% after, P < .001). However, prophylaxis rates remained low during observed calendar years (Figure 2). In addition, IDEL use among Medicare beneficiaries sharply decreased following the manufacturer’s communication (P < .001 for FL and CLL) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of Study Medicare Beneficiaries Receiving IDEL and PJP Prophylaxis by Indication and Calendar Month.

CLL indicates chronic lymphocytic leukemia; FL, follicular lymphoma; IDEL, idelalisib; PJP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. IDEL-treated beneficiaries were identified from July 2014 (approval) through September 2016 and were followed through March 2017. Note that the first prescription that fulfilled all study entry criteria did not occur until August 2014. PJP prophylaxis was defined as on-treatment receipt of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pentamidine, atovaquone, dapsone, or clindamycin. The vertical dashed line represents the timing of the safety communications on risk for serious infections with idelalisib and the recommendation for PJP prophylaxis in all IDEL-treated patients.

Discussion

Medicare beneficiaries treated with IDEL had more comorbidity at baseline compared with participants aged 65 years or older in pivotal trials. These differences may have arisen from trial eligibility criteria, which often exclude comorbidities that could negatively affect tolerability. Although eligibility in Study 312-0116 was driven by comorbidities precluding treatment with cytotoxic agents, patients with CLL in the clinical setting still had higher comorbidity. Unintentional biases may contribute to the health status of patients accrued to clinical trials. For example, IDEL-treated trial participants had a 1.8-fold lower rate of diabetes (15.3% vs 27.9%) and a 2.4-fold lower rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12.8% vs 31.1%) than Medicare beneficiaries, despite neither condition being specifically excluded.

Our study findings are consistent with an internal FDA review of eligibility criteria for oncology trials, finding most trials had a narrowly defined population of lower-risk patients.13 Efficacy and tolerability may be meaningfully different for optimally selected and closely monitored trial participants compared with unrestricted patients in the clinical setting.14,15

Observed comorbidity imbalances are a probable explanation for observed imbalances in treatment outcomes. However, it was noteworthy that dose reductions were approximately 2-fold more frequent among trial participants. This may be attributable to some extent by a decision to discontinue therapy rather than reduce the dose in the clinical setting. Closer follow-up combined with enhanced patient education may have reduced severe toxic effects in clinical trials, including immunosuppression-related adverse events and serious infections. This parallels a recent reanalysis of idelalisib trial data, finding that patients who interrupted treatment had a longer treatment duration, progression-free survival, and overall survival.16 These data suggest additional monitoring for toxic effects, and dose interruptions and reductions where appropriate, are needed in clinical practice. A dose optimization study is ongoing for FL, which evaluates a lower dosage, 100 mg twice daily, and the effect of a 7-day drug holiday per 28-day cycle on toxic effects.17

Fatal infection rates in clinical practice were high, particularly in the first 6 months of IDEL-treatment. Four fatal PJP cases were observed, none of which received prophylaxis. We additionally identified a 2.11-fold increased risk for fatal on-treatment infection among Medicare beneficiaries treated with idelalisib with a recent hospitalized infection. This is in line with a safety communication to not initiate idelalisib with ongoing systemic bacterial, viral, or fungal infections.3

We observed commonplace off-label use of IDEL monotherapy for CLL. Although not reviewed by the FDA, IDEL for CLL was given a level 2A recommendation (ie, panel consensus from low-level evidence) by National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines.18 This off-label IDEL use may have been influenced by studies suggesting high antitumor activity with IDEL monotherapy in both relapsed or refractory CLL (phase 1)19 and for previously untreated CLL in patients aged 65 years or older (phase II).20 In our study, Medicare beneficiaries receiving IDEL for CLL had relatively high baseline comorbidity and observed high rates of early treatment discontinuation and early mortality (eTable 1, eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

It is also noteworthy that 51 Medicare beneficiaries received IDEL+R for FL. This combination regimen was associated with unacceptable toxic effects in Study 313-0124 and is not recommended.1,21,22

Strengths and Limitations

This study provides findings from patients in the clinical setting supporting recent warnings for serious infections. Although clinical trials and Medicare have near complete capture of treatment duration and mortality, trial data have a more complete capture of comorbidity and prior drug therapy. Not all contributing causes of death could be identified; however, our focus was on serious infections within 30 days of death. Finally, risk for serious infections with IDEL has a clinical complexity that has not been fully elucidated, where risk may differ by indication, extent of prior treatment, immunocompetence, naive vs refractory use, disease severity, comorbidity burden, and concomitant medications.

Conclusions

We observed substantial differences between trial participants aged 65 years or older and Medicare beneficiaries for baseline clinical comorbidity. This example supports FDA initiatives to broaden trial eligibility criteria and bridge the gap between clinical studies and the intended treatment population. Our study findings also suggest a recent serious infection may represent a negative prognostic factor and warrant caution regarding IDEL initiation in such patients. Compliance with PJP prophylaxis and close monitoring of absolute neutrophil counts, with appropriate dose interruptions and reductions, may help reduce the rate of serious infections.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics for Medicare beneficaires receiving off-label IDEL for CLL and IDEL+R for FL

eTable 2. Rates of serious and fatal infections by anatomical location per 100 person-years by study cohort

eTable 3. Serious and fatal infection counts by infection type among all subjects and beneficiaries

eTable 4. Infectious organisms present in Medicare beneficiaries during inpatient stays or coded with receipt of an antibiotic

eFigure1. Reasons for censoring by 90-day therapy increment in time to treatment discontinuation analysis among Medicare beneficiaries and trial subjects by study cohort

eFigure 2. Estimated hazard ratio for treatment discontinuation over time, Medicare vs. clinical Trial

eFigure 3. Hazard ratio for treatment discontinuation and mortality among clinical trial patients and Medicare beneficiaries with each 1-Unit increase in Charlson score

eFigure 4. Rates of serious infections by study cohort for ≤6 versus >6 months of idelalisib treatment

References

- 1.Zydelig (idelalisib) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2018.

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . FDA alerts healthcare professionals about clinical trials with Zydelig (idelalisib) in combination with other cancer medications. https://www.fda.gov/ Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm490618.htm?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 3.Gilead Sciences. Dear Health Care Provider Letter; decreased overall survival and increased risk of serious infections in patients receiving Zydelig (idelalisib). http://cllsociety.org/docs/ Zydelig%20Safety%20Update.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 4.European Medicines Agency . EMA recommends new safety measures for Zydelig. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2016/03/news_detail_002490.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 5.Gopal AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S, et al. PI3Kδ inhibition by idelalisib in patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):1008-1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):997-1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Council for harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. MedDRA: Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. https://www.meddra.org/. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 8.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill ME, Rosenwaike I. The Social Security Administration’s Death Master File: the completeness of death reporting at older ages. Soc Secur Bull. 2001-2002-2002;64(1):45-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . What is a serious adverse event? https://www.fda.gov/ Safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/ucm053087.htm. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 12.National Cancer Institute . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 13.Jin S, Pazdur R, Sridhara R. Re-evaluating eligibility criteria for oncology clinical trials: analysis of investigational new drug applications in 2015. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3745-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaver JA, Ison G, Pazdur R. Reevaluating eligibility criteria – balancing patient protection and participation in oncology trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1504-1505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1615879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Food and Drug Administration . Cancer clinical trial eligibility criteria: patients with HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C virus infections guidance to industry. https://www.fda.gov/down loads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM633136.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 16.Ma S, Chan RJ, Ye W, et al. Survival outcomes following idelalisib interruption in the treatment of relapsed or refractory indolent Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132:3149. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. National Library of Medicine . Dose optimization study of idelalisib in follicular lymphoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02536300. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 18.Wierda WG. Updates to the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(5)(suppl):662-665. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JR, Furman RR, Flinn I, et al. Final results of a phase I study of idelalisib (GSE1101) a selective inhibitor of PI3Kδ, in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15)(suppl):7003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelenetz AD, Lamanna N, Kipps TJ, et al. A phase 2 study of idelalisib monotherapy in previously untreated patients ≥65 years with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) or Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL). Blood. 2014;1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. National Library of Medicine . Efficacy and safety of idelalisib (GS-1101) in combination with rituximab for previously treated indolent Non-Hodgkin lymphomas. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01732913. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 22.Leonard J, Zinzani PL, Jurczak W, et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of idelalisib (GS-1101) in combination with rituximab for previously treated indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15)(suppl):TPS8617. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics for Medicare beneficaires receiving off-label IDEL for CLL and IDEL+R for FL

eTable 2. Rates of serious and fatal infections by anatomical location per 100 person-years by study cohort

eTable 3. Serious and fatal infection counts by infection type among all subjects and beneficiaries

eTable 4. Infectious organisms present in Medicare beneficiaries during inpatient stays or coded with receipt of an antibiotic

eFigure1. Reasons for censoring by 90-day therapy increment in time to treatment discontinuation analysis among Medicare beneficiaries and trial subjects by study cohort

eFigure 2. Estimated hazard ratio for treatment discontinuation over time, Medicare vs. clinical Trial

eFigure 3. Hazard ratio for treatment discontinuation and mortality among clinical trial patients and Medicare beneficiaries with each 1-Unit increase in Charlson score

eFigure 4. Rates of serious infections by study cohort for ≤6 versus >6 months of idelalisib treatment